1. Key insights on preparing vocational teachers and trainers

This chapter provides an overview of the report and a summary of the key findings and lessons learnt from the case studies of five countries: Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Norway. It highlights the roles and importance of teachers and in-company trainers in vocational education and training (VET), strategies to prepare these teachers and trainers, and the role of entry requirements and initial teacher and trainer training.

Teachers and in-company trainers are central to vocational education and training (VET). They play an important role in developing learners’ skillsets in line with labour market needs, by teaching and training not only occupational skills but also transversal skills, such as basic and socio-emotional skills. They support the school-to-work transition of students with diverse backgrounds, including adults in need of new, updated, or improved skills (OECD, 2021[1]). Box 1.1 provides definitions of VET teachers and trainers.

Digitalisation, automation, and the transition to a low-carbon economy are having an impact on the skills needed in the labour market, and therefore also on the skills that need to be formed through VET. Some of these trends have been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. These changes in skill needs necessitate changes to VET curricula – both school-based and work-based learning – and therefore also to the skillset of VET teachers and trainers. Moreover, as pedagogical approaches evolve, including due to technological advances in the education sector, VET teachers and trainers need to keep abreast of these changes to be able to effectively teach and train their students. In particular, newly recruited VET teachers and trainers should be equipped not only with up-to-date knowledge and skills in their field but also with strong pedagogical skills and awareness of new approaches to teaching (OECD, 2021[1]).

In general, VET teacher refers to teacher of vocational theory or practice (and in some cases, teacher of general subjects) in school-based VET, and VET trainer to in-company trainer who train practical and technical work during the time when apprentices receive training in a company.

Teachers of vocational theory teach theoretical subjects related to the vocational field, such as sales techniques and electronics, in VET programmes.

Teachers of vocational practice teach practical applications, such as mechatronics practice in school workshops, in VET programmes.

Teachers of general subjects are responsible for teaching academic subjects, such as mathematics and sciences, in VET programmes.

VET trainers are individuals who provide training to VET students during their work placement with companies.

These definitions are not always clear-cut, partly because in some countries in-company trainers or industry professionals may teach in school-based VET.

As the terminology for these professions differs across countries, the section ‘VET teachers and trainers’ in each of the following chapters provides more detailed definitions and characteristics in each country.

Countries have a different mix of school-based and work-based learning in VET programmes (see Figure 1.1, Panel A), and this has implications for the demand for teachers and trainers and their skill requirements. In some countries, VET is predominantly organised as school-based learning (e.g. Italy, Sweden), whereas in others the large majority of VET students are in programmes with a substantial work-based learning component (e.g. the Netherlands, Switzerland). The proportion of time spent in school and the workplace within VET programmes differs widely between countries and even between different programmes within the same country (see Figure 1.1, Panel B). For example, apprentices in Austria, Germany and Switzerland spend only around 20-25% of their time in school-based training, whereas apprentices in Sweden split their time equally between school and the workplace.

1.1.1. VET teachers need a sophisticated mix of knowledge and skills

Teachers in VET require multiple layers of skills and experience. VET teachers need to have both theoretical and practical knowledge and skills, and sometimes require relevant experience for the profession they teach. They also need to have the capacity to effectively transfer their knowledge and skills to students. Given that students in VET are often very diverse – including young people in initial education and adults who are upskilling or reskilling –, VET teachers also need to be able to work with students with very different backgrounds, motivations and aspirations. VET can attract some learners who are less engaged by traditional forms of teaching and learning or who are at risk of dropout, and VET teachers need the pedagogical knowledge and skills to effectively engage with these learners. In many countries, learners in VET have weaker basic skills – such as literacy or numeracy – than those in general education, and thus VET teachers need to be able to identify possible basic skills gaps and contribute to closing them. Moreover, teachers in VET increasingly need to develop the digital and socio-emotional skills of their students, as these are increasingly in demand in the labour market. To do this, teachers need to have knowledge of innovative pedagogical approaches that foster the development of these skills. They also need to have strong digital skills themselves, to be able to use new technologies in teaching, and remain up to speed with technological innovations in the workplace. As an example of the required mix of skills, Box 1.2 describes the essential1 skills and knowledge for VET teachers in the fields of hairdressing and business administration according to the European Skills, Competences, Qualifications and Occupations (ESCO) framework.

VET teachers usually acquire their knowledge and skills through years of study and practice, leading to a VET teaching qualification. Most VET teachers have a tertiary degree, although in most OECD countries their level of attainment is lower compared to general education teachers (Figure 1.2). However, the majority of countries require VET teachers to have teaching qualifications of at least ISCED Level 5 (short-cycle tertiary) or above (OECD, 2021[1]).

The European classification of skills, competences, qualifications and occupations (ESCO) describes, identifies and classifies occupations and skills relevant for the European Union (EU) labour market. ESCO profiles show whether certain skills and knowledge are essential or optional for certain occupations and what qualifications are relevant for each occupation. ‘Essential skills’ are the skills usually required when working in an occupation, independent of the work context or the employer. ‘Optional skills’ refer to skills that may be required or occur when working in an occupation depending on the employer, working context or country.

ESCO contains occupational profiles for various VET teachers. Table 1.1 shows the essential skills and knowledge listed in the profiles of hairdressing teachers and business administration teachers. The skills and knowledge requirements reflect that VET teachers need a mix of pedagogical skills to build course content, develop and assess a range of hard and soft skills among students, support a diverse group of students and manage the classroom; industry-specific skills and knowledge that they can transfer in a safe way; and the ability to keep abreast of changes in the labour market.

1.1.2. In-company trainers need to be able to support students’ learning journeys in the workplace

Teachers in VET institutions are not the only ones in charge of supporting skills development among VET students. Many VET programmes contain elements of work-based learning (WBL), which means that part of the curriculum is delivered by employers in the workplace. To ensure that students make the most of their time in the workplace and effectively develop their skills while working, they need the support of experienced co-workers who take charge of training VET students. These in-company trainers need to transfer their knowledge and practical skills to the student, but also support the student more broadly in navigating the workplace and developing skills that can increase employability. They may also provide on-the-job training to current employees, in addition to apprentices and other VET learners. Box 1.3 describes the essential skills and knowledge for trainers according to the ESCO framework.

ESCO (see Box 1.2) contains occupational profiles for corporate trainers (training and staff development professionals), which can in some case correspond with VET trainers. Corporate trainers train, coach, and guide employees of a company to teach and improve their skills, competences and knowledge in accordance with the needs of the company. They develop the existing potential of the employees to increase their efficiency, motivation, job satisfaction, and employability.

Table 1.2 shows the essential skills and knowledge listed in the ESCO profile of corporate trainers. While in-company trainers are often regular employees who combine their normal work activities with training of VET students, the skills and knowledge requirements for the training part of their job will be similar to those of a corporate trainer listed below.

Trainers are typically recruited within the company, often as part of their career advancement as trainer (Hensen and Hippach-Schneider, 2016[7]). The tasks of in-company trainers generally include planning and delivering training, and reflecting on teaching and learning processes in the workplace. They accompany learners, support low-performing learners, manage heterogeneous groups and solve individual problems, such as imminent discontinuation of training, loss of motivation or insufficient integration into the company (BIBB, 2015[8]; Hensen and Hippach-Schneider, 2016[7]). In addition, trainers can also be involved in determining company-wide qualification needs. Cooperation with the staff in human resource development and work organisation is also among the tasks of the trainers (BIBB, 2015[8]). In-company trainers have an important role in helping students and apprentices in the work environment develop a professional identity and occupational profile. In small enterprises, the trainer is a crucial role model for the following generation of employees (Cedefop, 2019[9]).

1.1.3. Shortages of teachers and trainers in VET are common

A well-prepared teaching and training workforce that holds the right set of skills is vital for quality VET provision. Nonetheless, various countries struggle in bringing on board a sufficient number of skilled VET teachers and in encouraging employers to provide work-based learning opportunities supported by skilled trainers. There are many factors that contribute to such shortages. Allowing for flexible entry and preparation of teachers and trainers while maintaining the quality of the workforce –which is the focus of this report- is one of the strategies that can help overcome shortages, alongside efforts to make the teaching and training profession more attractive.

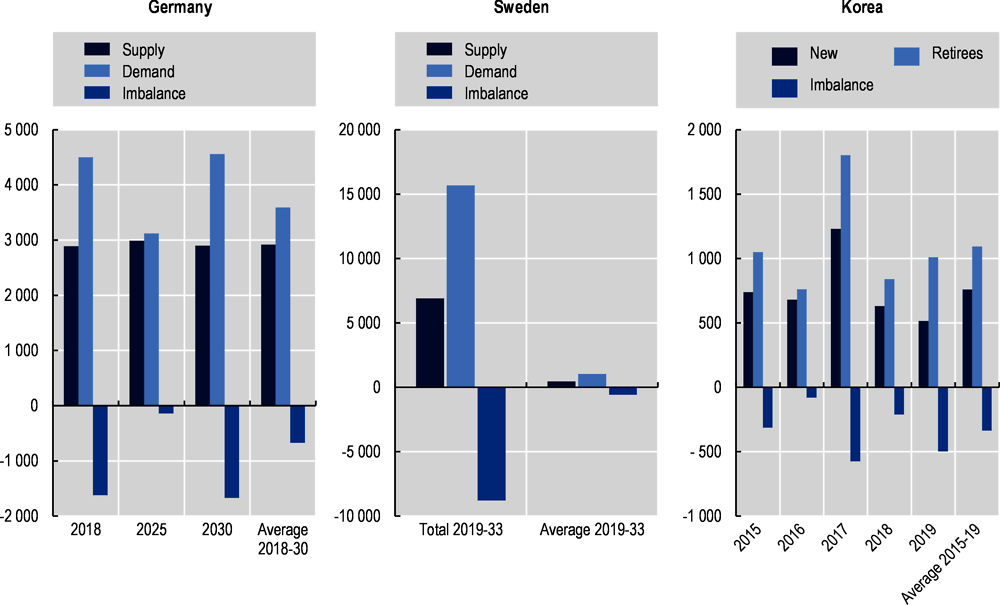

In several OECD countries, there is considerable concern about shortages of VET teachers. For example, a survey in the United States reports that for 98% of surveyed state directors of VET addressing shortages of qualified VET teachers had been a key priority for their state and all those state directors indicated that this would be a priority for their state in the future (Advance CTE & CCSSO, 2016[10]). Other research indicates that as many as half of the states across the country have major shortages of VET teachers, and more than half of states reported that they have teacher shortages in one or more VET subject (2018-19 Teacher Shortage Areas in the United States) (OECD, 2021[1]). In Germany, it has been estimated that the supply of VET teachers would meet only about 80% of the demand per year between 2018 and 2030 (Figure 1.3, Panel A) (KMK, 2019[11]). The German Education Union (GEW) estimated an even greater shortage based on a larger estimated number of VET students (Dohmen and Thomsen, 2018[12]). In Sweden, a forecast by the Swedish National Agency for Education shows a risk of a shortage of trained upper secondary VET teachers. The agency estimated the supply of new VET teachers to be less than half of the demand for 2019-33 (Figure 1.3, Panel B). Alternative calculations have assumed higher retention rates for VET teachers, but even these indicate future shortages (Skolverket, 2019[13]). In Korea, information based on the number of teacher entrants and retirees shows that the supply of new VET teachers reached only about 70% of the replacement need in the past five years (Figure 1.3, Panel C).

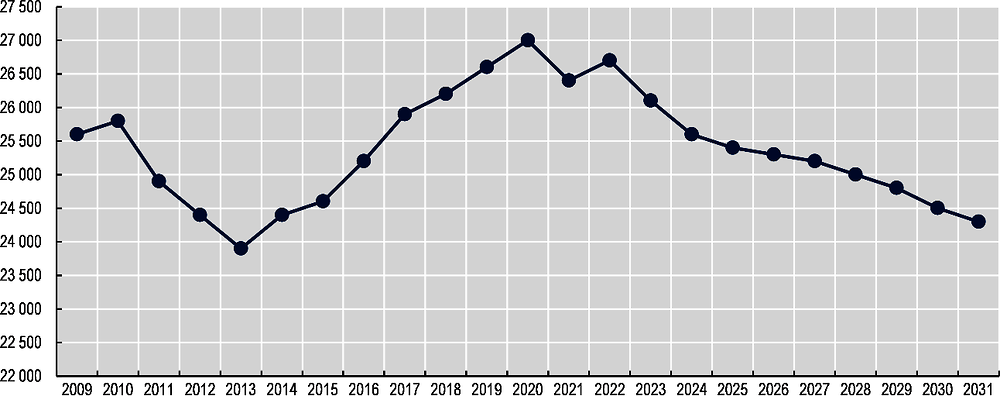

While some countries foresee a falling need for VET teachers, policies on teacher recruitment and initial teacher education and training still play a role in avoiding shortages in certain fields or regions. For example, the Netherlands has succeeded in increasing the number of VET teachers in the past decade, in particular younger teachers – even in the context of declining numbers of primary and secondary education teachers. In the coming decade, due to an anticipated significant drop in student numbers, the Netherlands forecasts a lower demand for VET teachers (Figure 1.4): the required number of upper secondary VET teachers is expected to decrease by about 9% between 2020 and 2030 (OCW, 2020[14]). However, new entrants will still be required to offset retirements and other exits from the profession, and subject-specific shortages may still emerge (CentERdata, 2021[15]). In Denmark, while there are fewer students entering VET than in the past (upper-secondary VET enrolment has decreased from 43% of all upper-secondary students in 2013 to 38% in 2018), this does not automatically lead to a lower demand for VET teachers because specialised courses are still maintained despite reduced enrolment – which may not be sustainable in the long run. 37% of VET school leaders in Denmark reported that shortages of qualified teachers significantly hinder their school's capacity to provide quality instruction, according to data from the 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS). These examples show that even when it is expected that the number of VET teachers will go down, shortages are likely in certain fields. Moreover, the age profile of the VET teacher population implies that there remains a need for new VET teachers – in these two countries, more than half of VET teachers are 50 years old or over (OECD, 2021[1]).

There are many factors that contribute to teacher shortages, many of them related to limited attractiveness of the VET teaching profession, including employment conditions, salaries, and a lack of financial incentives and career support (OECD, 2021[1]). There can be fierce competition for talent with other sectors or roles which may offer more attractive working conditions. Various strategies are being adapted to make the teaching profession more attractive, combined with efforts to overcome possible barriers to entry. Restrictive entry requirements and lengthy and intensive preparation could be part of the problem, as they may discourage potential VET teachers – especially those coming from industry – to enter the profession. Attracting industry professionals into the teaching profession is one of the key strategies for ensuring an adequate supply of VET teachers with relevant skills and knowledge, and this requires providing flexible pathways into the profession and mechanisms to ensure that these professionals have the right mix of skills – including pedagogical skills.

Hiring part-time VET teachers – which often coincides with “side entry”, “lateral entry” or “hybrid teaching” in VET by professionals from industry (see case studies for Germany and the Netherlands) – can facilitate flexible teaching in VET, if teachers’ working conditions are not compromised. Part-time VET teachers with industry backgrounds can bring a number of benefits to the VET system, such as overcoming teacher shortages, reducing costs, increasing flexibility in VET provision and bringing in up-to-date knowledge from industry. Part-time teaching can also allow teachers to combine teaching with training to obtain a VET teaching degree. According to the 2018 TALIS data, a flexible working schedule such as part-time teaching was the most commonly reported reason for becoming a VET teacher (68% of respondents) across the countries with available data. Moreover, VET teachers were more likely to be attracted to the profession by the flexible working hours than general education teachers (60%) (OECD, 2021[1]). The Netherlands is one country that makes extensive use of flexible entry, including lateral entries and part-time employment. It has one of the highest shares of part-time employment among upper-secondary VET teachers among EU countries in 2019 (Figure 1.5) – in line with an overall relatively high share of part-time workers in the Dutch labour market.

Imbalances for in-company trainers are harder to assess. While there are no data available on the supply of and demand for trainers or firms’ training capacity, there is generally a close connection to overall skills shortages in the relevant sectors and occupations. In-company trainers are usually skilled workers who combine regular work with training responsibilities. Hence, in sectors and occupations that are facing labour or skills shortages, there are likely also trainer shortages – and firms may even cut training activities due to shortages. At the same time, companies tend to train their workers when facing skill shortages, which could increase the demand for in-company trainers.

However, it should be noted that as with VET teachers, the shortage issue among in-company trainers, if any, is not only about the labour availability, but other factors such as salaries and working conditions also matter (OECD, 2021[1]; Huismann and Hippach-Schneider, 2021[16]). In addition, the shortage may be related to the skills of trainers themselves, especially when they are not specifically trained to provide and manage in-company training.

1.2.1. Entry requirements for the VET teaching and training profession are set to ensure quality

Many countries set entry requirements for the VET teaching and training profession, such as having a teaching qualification, vocational qualification and/or work experience, in order to ensure quality of teaching and training in VET. Entry requirements and training standards differ across countries. They also differ across programmes and subjects taught – and even across VET providers – and sometimes depend on the level of teacher shortages in the field (OECD, 2021[1]).

It is important to provide multiple and flexible ways to recruit and qualify VET teachers (OECD, 2021[1]). For example, for skilled professionals in the middle of their career, having to start full-time education leading to the required teaching qualification can constitute too big of a barrier. These professionals have valuable work experience or new types of skills and knowledge that the current entry requirements or training programmes of teachers do not yet cover (OECD, 2021[1]). To avoid that candidates with relevant skills are discouraged from entering the profession, several countries provide alternative pathways for industry professionals to join the VET teaching workforce. These entry routes generally have relatively less stringent requirements or give more flexibility to achieve the standard requirements.

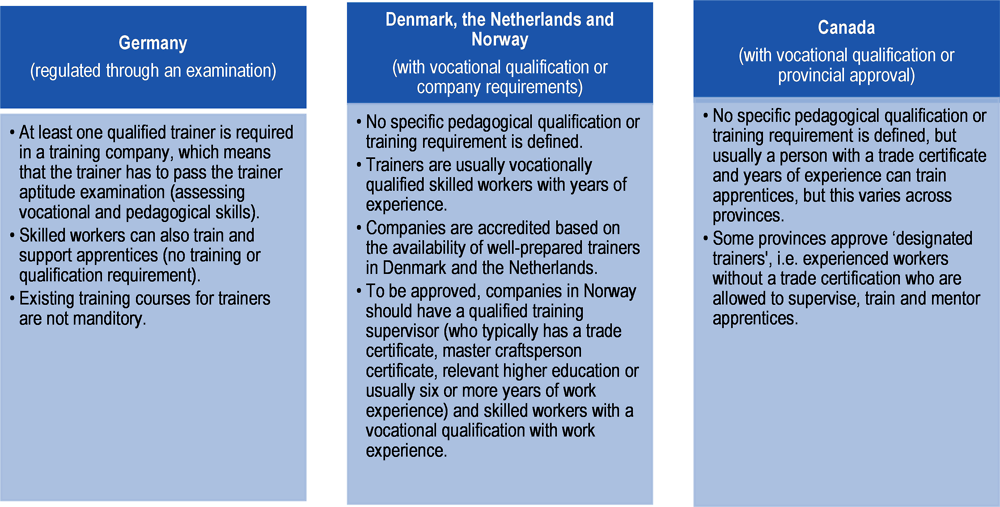

Likewise, in order to ensure that the work-based learning on offer in VET programmes is of high quality, countries introduce standards and regulations regarding the organisation and delivery of in-company training, including in some cases requirements for trainers. For example, Austria and Germany impose a number of prerequisites for apprenticeship training including a sufficient number of professionally and pedagogically qualified trainers (e.g. five apprentices per part-time trainer or 15 apprentices per full-time trainer in Austria, and at least one qualified trainer in each company in Germany). This is based on the recognition of the fact that the success of company-based apprenticeship training is determined by the trainer’s professional competence and pedagogical skills (Cedefop, 2019[18]). However, the degree of regulation and training provision for trainers varies significantly across countries. Some countries set requirements for trainers in terms of qualifications, skills and work experience. For example, it is often required or advised that trainers have a relevant vocational qualification. In some cases, in-company trainers need to have obtained a specific training qualification or certification, as is the case in Austria and Germany for example. Box 1.4 describes how a few countries (not covered by the case studies in this report) impose requirements on the qualifications or skills of in-company trainers to be able to provide work-based learning. Nonetheless, many countries do not impose any specific requirements on in-company trainers related to pedagogical or training-relevant qualifications or skills, as imposing such requirements could create barriers, particularly among SMEs, and imply costs.

Austria

Trainers at workplaces in Austria must be qualified to provide apprenticeship training. One of the ways to be qualified as an in-company trainer is to obtain a trainer qualification. This can be acquired as part of a trainer examination or a successfully completed trainer course. The trainer examination is organised by the master’s examination offices of the Chamber of Commerce. Preparatory courses for the trainer examination are offered by the economic development institutes of the Chamber of Commerce (WIFI) and the professional development institutes (bfi). The following specialist knowledge must be proven within the framework of the trainer examination or the technical discussion after the trainer course:

Knowledge of the Vocational Training Act (BAG), the Child and Youth Employment Act, employee protection and the position of the dual system in vocational training in Austria.

Trainer exams can be as part of the master craftsman's examination or qualification examination, or be organised as a separate examination in front of an examination committee. Other ways for trainers to be qualified are attending a 40-hour course or passing an exam organised by the economic chambers to prove professional pedagogical skills and legal knowledge. In certain professional fields such as notary, auditor or civil engineer, specialised examinations or training courses (e.g. notary examination, specialised examination for auditors and tax consultants, or civil engineer examination) may qualify professionals in these fields as trainer.

Estonia

The national legislation of Estonia does not require in-company trainers (vocational trainers and apprentice trainers) to have specific qualifications or competences. However, VET institutions are responsible for providing in-company trainers with the necessary training. They organise seminars and training courses, supervise and support in-company trainers. The purpose of the training is to raise the quality of supervision during work placement and the efficiency of training. The course is between 8 to 40 hours long and participants receive a certificate. Training relates to preparing, administering and evaluating work practice, and includes for example didactics, supervision and training provision; curriculum objectives and assessment principles; work practice and supervision for special education needs students.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, trainers at companies providing apprenticeships have to have a special qualification, which is awarded upon completing a course for vocational trainers in training companies lasting 40 hours (five days) or attending 100 hours (spread over six to eight months) of training in pedagogy, VET law, VET system knowledge, and problem solving methods for adolescents. The candidates receive a federally recognised certificate or diploma, respectively. VET trainers for intercompany courses have to complete 600 hours of pedagogy preparation and there are also special requirement for examiners. In addition to formal requirements, Switzerland provides in the QualiCarte a checklist of 28 quality criteria whereby host companies can self-assess their training capacity and quality for improvement.

Source: WKO (2019[19]), In-company trainers, https://www.wko.at/service/bildung-lehre/Ausbilder.html; Ministry of Education and Research of Estonia (2017[20]), Background Report for OECD on Vocational Education and Training; Hoeckel, Field and Grubb (2009[21]), A Learning for Jobs Review of Switzerland 2009, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264113985-en; OECD (2010[22]), Learning for Jobs, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264087460-en.

1.2.2. Initial education and training for VET teachers and trainers takes many shapes and forms

Initial teacher education and training (ITET), which allows future teachers to obtain necessary skills and qualifications, is a vital element of teaching in VET. Designing appropriate ITET programmes for VET teachers is important to ensure a good mix of pedagogical skills, vocational competence and industry knowledge. VET teachers’ educational attainment, together with work experience and continuous learning opportunities, have a significant effect on their teaching competence (OECD, 2021[1]). In particular, training in pedagogical skills is key for VET teachers who are joining the teaching sector from industry.

ITET is organised differently across OECD countries. It usually takes the form of a teacher-training degree course at the tertiary education level. In some case, this includes practical training. Some countries have national or sub-national examination(s), usually at the end of the programme. In these countries, the design and content of ITET is closely linked to national or sub-national qualification requirements. ITET is often provided by institutions of higher education or a public agency specialising in ITET, but could consist of multiple components that are provided by different institutions. Different organisations may provide training in vocational subjects or pedagogical knowledge while certification of knowledge and skills may be awarded by other organisations. Several countries provide targeted financial support to help future VET teachers benefit from ITET (OECD, 2021[1]). ITET may be organised differently for those coming from industry through more flexible pathways, in recognition that they often already hold some of the skills targeted by ITET and that they may need the flexibility to combine a teaching job and ITET.

The effectiveness of ITET is well evidenced. TALIS data show that VET teachers who benefitted from training in specific teaching responsibilities or tasks in their ITET felt more prepared for taking up these responsibilities in their teaching (Figure 1.6). In some countries, existing arrangements for ITET do not seem to provide the full mix of skills VET teachers require (OECD, 2021[1]). For example, ITET for VET teachers appears to be weaker at developing pedagogical skills than ITET for general education teachers. A non-negligible share of VET teachers in selected OECD countries still felt unprepared in general pedagogy (16%) and subject-specific pedagogy (17%) even if they had undertaken ITET in those areas (Figure 1.6). In general, ITET for VET teachers appears to be weaker at developing pedagogical skills than ITET for general education (Figure 1.7). It should be noted that these data cover a limited set of countries and that more data and research would be needed to analyse the link between the design and content of ITET and the feeling of preparedness of VET teachers.

Dedicated preparation for in-company trainers does not always exist. However, there are some countries, including Austria, Germany and Switzerland, that regulate certain minimum requirements for trainers and have a dedicated training offer for trainers (Box 1.4). For example, Germany offers extensive optional training for trainers: training courses for trainers that prepare for the trainer aptitude exam are often provided by the Chambers of Industry and Commerce and Crafts, they are built into Mastercraftsperson courses) and many programmes at universities of applied sciences also offer the training courses for trainers (see Chapter 4). Even in countries where trainers are not required to have a specific training qualification, optional training programmes are often provided. Providers and content of training varies from country to country.

The remaining chapters of this report describe how entry requirements and preparatory training for teachers and in-company training are implemented in five case study countries: Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Norway. This section describes the lessons learnt from across these five countries, with a focus on how they manage to develop a skilled teaching and training workforce through entry requirements and training, while maintaining sufficient flexibility to be able to attract teachers and trainers to the profession.

1.3.1. Entry requirements for VET teachers

The five countries covered in this report all have different entry requirements for VET teaching professionals. Differences within countries also exist, and this is especially the case in Canada where provinces and territories as well as individual training providers are the main actors determining requirements and training. In general, all five countries require teachers to have a vocational and pedagogical qualification, either separately (Denmark, Norway, most provinces in Canada) or combined into one single qualification (Germany, Norway and Netherlands – depending on the pathway). Relevant work experience is also required in some cases, and this can be obtained as a mandatory part in the ITET (Germany) or outside of ITET (Norway, Denmark). Entry requirements often vary depending on the field, entry route and characteristics of the teacher candidate. Moreover, some countries also impose different requirements for those teaching vocational theory and practice (Germany, Denmark and Norway) or for teaching support roles (“instructors” of vocational practice in the Netherlands). Countries that have relatively strict regulations for the qualification of VET teachers, such as Germany and the Netherlands, provide alternative -more flexible pathways- (side entry) to the profession for individuals coming from industry.

Setting clear entry requirements that contribute to the quality of teaching

All five countries analysed in this report impose entry requirements to the VET teaching profession in terms of qualifications and/or experience. Nonetheless, they differ in how demanding these requirements are:

In Germany, teachers of vocational theory have to pass two state examinations following a university teacher training and a preparatory service (i.e. teaching practicum). Teachers of vocational practice, who usually already have a vocational qualification, have to complete a pedagogical training and a preparatory service, and pass a state examination.

In Norway, an educational or vocational qualification in the relevant subject, four years of work experience (with some exception) and a teaching qualification (pedagogics and didactics) are required to teach in VET.

In Denmark, while the requirements depend on the type of VET programme, the subject taught and VET provider, prospective VET teachers in upper-secondary VET are required to have a formal qualification related to the subject area (typically a journeyman’s certificate or a bachelor degree). At the post-secondary level, the majority of teachers typically hold bachelor’s or master’s degree. The Diploma in VET-pedagogy (DPE), at the professional bachelor level, is usually required to teach at both levels. The DPE must be started in the year after the VET teacher begins the job at the VET institution and must be finished within four years.

In the Netherlands, a teaching qualification at bachelor or master level is required for upper secondary VET teachers (or a pedagogical and didactic certificate for those coming from industry, see below). Instructors of vocational practice in upper secondary VET require pedagogical and didactic competence, which they can acquire through dedicated training programmes (at ISCED level 4 or 5). Teachers of professional bachelor or master programmes in universities of applied science usually have to obtain a didactical qualification together with work experience, although requirements vary across VET providers.

In Canada, requirements vary across provinces and territories, VET providers, teaching fields or programme levels, with no single standard for VET teacher credentials. The completion of apprenticeship training, a trade certification, Bachelor of Education and/or practical work experience are usually required. For example, in the province of Quebec, a teaching qualification is required for secondary VET teachers, which can be obtained through a Bachelor of Education or a combination of other qualifications. In Manitoba, VET teachers in post-secondary level institutions require both trade certification and experience in the trade as well as a teaching certificate (which could be obtained after hiring), while in the province of Saskatchewan a vocational certificate confers eligibility to teach a specified subject in all school grades at upper secondary and below levels, although additional qualifications may also be needed depending on the provider.

Table 1.3 provides a general overview of requirements for upper-secondary VET teachers, and further details are provided in the case study chapters.

As most countries have various teacher qualifications or require a set of qualifications and skills, aspiring teacher candidates need to receive information about the requirements and training courses and how they can be prepared for and involved in the recruitment and training process. In particular, Canada has different requirements for VET teachers across provinces and territories and even across VET providers within the same province, which makes the landscape hard to navigate. Therefore, aspiring candidates should be well informed about different qualification and experience requirements.

Allowing for some flexibility without compromising on quality

All of the five countries offer multiple routes to enter the profession in an effort to overcome possible barriers. Such alternative and generally more flexible routes are always coupled with mechanisms to ensure that the pedagogical and professional knowledge and skills of (prospective) VET teachers are up to standards.

One common element of flexibility is to allow (certain) individuals to enter the teaching profession without the required qualification, under the condition that they obtain said qualification within a given time period. For example, Manitoba (Canada) and Denmark provide the option of obtaining the required teaching qualification while already teaching. Similarly, Norway allows candidates to temporarily fill teaching positions in times of teacher shortages even if they have not acquired the necessary teaching qualification yet. In the Netherlands, one of the pathways offers tailored training courses for teaching in VET without the standard required qualifications, by selecting candidates who already demonstrate professional competencies and focusing training on pedagogical and didactic elements, and allowing work-study combination. In Germany, while the entry requirements are quite demanding, side entrants have access to shortened and tailored training that helps them to meet pedagogical requirements and leads to a teaching qualification.

Given that many VET teachers are recruited and trained from industry, the teacher candidates should be well informed about varying entry routes and the additional training required to become a fully qualified teacher. In addition, this training should be tailored to the learning needs of the training participants (and shortened if necessary), based on rigorous assessment of their prior knowledge and work experience. In order to attract competent industry professionals and retain them, governments would need to ensure that these teachers also enjoy the same level of respect and working conditions and raise awareness about the value of bringing industry experience to the VET sector (OECD, 2021[1]).

1.3.2. Entry requirements for in-company trainers

Entry requirements for trainers are mostly related to vocational qualifications & experience

In general, in-company trainers in all five countries are expected to have a vocational qualification and years of experience, at varying degrees (see Figure 1.8). Only Germany imposes specific requirements regarding a training qualification – although some sectors, regions or companies in the other four countries may impose such requirements. In Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway, there is no specific trainer qualification required for trainers, and they are generally only expected to have a relevant vocational qualification and work experience. Moreover, there is no obligatory training for trainers in these countries. Nonetheless, in the Netherlands trainers are expected to have certain didactic skills and pedagogical competences, and sectors, such as commercial service and safety, specify as requirements for trainers that these competences need to be validated by diplomas or certificates. In Germany, trainers must have a relevant professional qualification and pass a trainer aptitude examination to demonstrate one’s vocational and pedagogical knowledge. Training companies need to be accredited in order to offer work-based learning for VET students and they must have at least one ‘qualified’ trainer (i.e. a trainer who passed the trainer aptitude examination).

While Denmark and Norway also assess companies on whether their trainers are able to provide quality work-based learning, these countries do not have formal criteria as Germany does. For example, companies interested in providing apprenticeship placements in Norway have to be assessed by the county vocational training board and receive the county authority’s approval to act as a training establishment. The company needs to appoint a training supervisor who bears the overall responsibility of the apprenticeship as well as one or more trainers.

Setting guidelines on skills of in-company trainers can foster training quality

Developing the training capacity of in-company trainers is beneficial for the quality of work-based learning, and therefore of the overall VET system. This can begin by establishing guidelines or standards for the pedagogical skills, knowledge and training practice of in-company trainers. These guidelines and standards could inform the development of optional or mandatory training programmes. Imposing strict entry requirements may discourage workers from wanting to engage in training of VET students, and could reduce the offer of work-based learning opportunities altogether if companies do not have qualified trainers. While flexibility in terms of entry requirements can help ensure that there is a sufficient number of trainers, it should not have negative consequences on the quality of training.

Among the five countries analysed in this report, only Germany established an examination to qualify trainers. Nonetheless, the requirement for in-company training provision does not require all the trainers to be qualified, but only to have at least one qualified trainer in the company who bears the overall responsibility for the apprenticeship. While the qualified trainer is in charge of developing, scheduling and conducting the training, skilled workers who do not possess a training qualification may provide daily workplace training and, thereby, support the qualified trainer. Germany experienced that removing the requirement of passing the mandatory examination to become a qualified trainer did not significantly increase the training offers while it did decrease the training quality. Based on this lesson, Germany has put in place various initiatives and incentives to support prospective in-company trainers to get relevant training and pass the examination to be qualified. For example, the trainer aptitude examination is part of Master craftsperson examination. The examination and trainer training courses are also an optional module for students in many universities of applied sciences. Germany also has a number of schemes that financially support individuals who take training courses in order to become trainer.

Rather than imposing specific training qualification requirements, other countries have introduced different strategies to ensure that trainers are well prepared for their role. Several countries provide dedicated training for trainers, without making participation and/or certification mandatory. Moreover, in some countries, workplaces need to get approved before they are allowed to deliver work-based training, and the quality or skills of trainers is often an element at play. In Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway, for example, skilled workers who are qualified in their trade usually offer work-based training. Although these countries do not require in-company trainers to have a specific trainer or pedagogical qualification, they ensure the training quality more generally by accrediting companies to be able to offer work-based learning – one of the criteria of such an accreditation is to have well prepared trainers. Similarly in Canada, certified journeypersons or other qualified trades workers train apprentices on the job without any specific pedagogical qualifications. However, in Canada, the interprovincial Red Seal Occupational Standards do specify mentorship activities and outline the skills and knowledge requirements to perform mentorship. Provinces and territories use these interprovincial standards to develop their respective apprenticeship programmes (both in-school and on-the-job training).

1.3.3. Initial training and preparation for VET teachers

All five countries covered in this report operate very different initial teacher education and training (ITET) systems:

In Canada, ITET is usually done through a bachelor’s degree programme in education with the option to follow a master’s and doctoral programme to expand their knowledge and expertise. The bachelor in education programmes mostly focus on pedagogy as VET teachers are usually expected to already have a VET qualification and relevant work experience – depending on the province, some Bachelor of Education programmes are 1-2 years and meant to be taken after completion of a 4-year Bachelor degree while some institutions offer a Bachelor of Technical Education or similar that only requires certification/experience in a technical field. In some cases, different types of tertiary institutions collaborate to offer initial teacher education and training (ITET) for VET teachers. For instance, while many universities offer 4-year Bachelor of Education programmes as ITET, very few universities provide ITET that trains prospective teachers to teach VET subjects at the same time. In contrast, colleges and technical institutes offer diploma programmes in vocational subjects, yet they cannot grant the Bachelor of Education degree, which is often a requirement or an advantage to become a VET teacher. For this reason, some universities, colleges and technical institutes form a partnership to offer a vocational teaching diploma by combining the pedagogic training from the university and vocational or technical teaching from the college or technical institute.

In Denmark, the VET-pedagogy diploma programme (DPE) is offered by university colleges, as part of the higher adult education system. It focuses on pedagogy adapted to the VET context, such as vocational pedagogical development work or digital technologies in VET. The duration of the programme can vary as teachers participate in this programme while working in a school, thus depending on how they adjust the teaching hours.

In Germany, a teacher training at a university includes a bachelor and a master programme and 52 weeks of practical work, followed by a preparatory service at a teacher-training college as teaching practicum. The process may vary depending on the subjects to teach and Länder.

In the Netherlands, ITET for prospective upper-secondary VET teachers is delivered by universities and universities of applied sciences. Teacher training in professional bachelor programmes is focused on a specific VET field, combining subject matter and pedagogy, ending with a compulsory teaching practice placement. Students with a non-teaching bachelor’s or master’s degree can also enrol in postgraduate or top-up programmes (with an important focus on pedagogy) to obtain a teaching qualification in the field related to their studies. The Pedagogical Didactic Certificate (PDG) for side entrants is delivered by professional tertiary institutions and is fully focused on pedagogy/didactics. Likewise, the training for vocational practice instructors focuses mostly on pedagogy and didactics, as participants are expected to have a relevant vocational qualification and/or work experience.

In Norway, universities and university colleges offer two bachelor-level ITET programmes: a vocational practical pedagogical education (PPU-Y) that focuses on pedagogy (1 year) and a vocational teacher education (YFL) that covers both vocational training and pedagogy (3 years). PPU-Y is for those who already have a professional bachelor’s or master’s degree; or a vocational certificate, a post-secondary qualification (ISCED Level 5) and a general university and college admission certification.

Flexibility is key in ITET for VET teachers

Flexibility is a key feature in ITET in all five countries. For example, mechanisms for recognition of the prior learning are well developed, and allow individuals with relevant skills and experience to take courses that are shorter than the regular ones.

In Denmark, the required DPE qualification can be obtained through full-time (one year) or part-time (up to 3 years) studies. VET teachers who do not meet the entry requirements for DPE can also start the DPE and complete some parts of it. This flexibility recognises that some professionals working in VET fields, such as plumbing or construction, do not have a post-secondary qualification and otherwise they would not be able to teach, and thus provides more opportunities for them to teach in VET with a full qualification.

In Norway, vocational practical pedagogical education (PPU-Y) can be completed through a one year full-time programme or two years part-time. While students in Norway may choose to follow an online ITET programme, they are still required to complete their practical training at schools, or in companies if they opt for the vocational teacher education.

Financial support schemes increase the accessibility of ITET

In most countries, ITET for VET teachers is part of the higher education system. ITET is usually financed by both the government and student tuition fees, with the balance between those two funding sources varying across countries and also between types of institutions in the same country. For instance, in Norway, students in a public institution do not pay tuition fees. All five case study countries have financial support schemes in place to help cover tuition fees and living costs. The support schemes comprise grants, loans (sometimes interest-free), scholarships and tax deductions – or some combination of these. Typically, these schemes have a set of eligibility criteria such as age or socio-economic status. For example, grant amounts are often contingent on the student’s financial and family situation and, depending on the type of grant, a certain standard of academic performance needs to be upheld. When teachers are participating in ITET while already teaching, it is sometimes the employing school that receives the financial support. In Norway, for example, school owners apply for education and recruitment grants for those teachers or teacher candidates who have not obtained their necessary teacher education yet.

Balancing the autonomy of ITET providers with quality assurance mechanisms

The ITET providers in all studied countries have a certain level of autonomy in designing their own ITET programmes, though at varying degrees across countries and sub-national entities. In this context, to maintain and improve the overall quality of ITET and to achieve consistency and coherence in the qualification and training system for ITET, quality assurance mechanisms have been established. These mechanisms are organised at different levels – from the national or sub-national level, to the level of (associations of) providers.

In Canada, due to provincial autonomy regarding academic matters, each university can define its own standards and procedures for quality assurance; yet, these have to be reviewed by relevant provincial or territorial quality assurance authorities – e.g. agencies or organisations that represent the provincial or territorial universities, the provincial or territorial governments, or even a combination of these. For example, the Ontario College of Teachers reviews and accredits teacher education programmes based on the province’s regulation requirements, including the provision of mandatory courses and teaching practicum.

In Denmark, while higher education institutions can decide which approach and method for quality assurance they want to apply, they are legally required to establish internal quality assurance procedures and to conduct systematic quality assurance of their provision. They are also legally obliged to make the quality evaluation results public, and their internal quality assurance work will be assessed through accreditation procedures. In addition, the ministry in charge of higher education has to approve diploma programmes for VET teachers and social partners are also involved in developing those programmes.

In Germany, each state ministry governs its ITET through their own regulations, which teacher training providers use to set the programme requirements. While each state has established their own regulations, the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (Kultusministerkonferenz, KMK) defines common content requirements, recommends completion requirements of the programmes, and adopts resolutions to ensure the quality and coherence of ITET.

In the Netherlands, the curriculum, teaching methods and requirements of teachers differ across the ITET providers, but there are several mechanisms to ensure the quality of ITET, and coherence in course requirements and instruction methods in different programmes. For example, self-evaluation mechanisms for the quality of ITET in each institution are complemented by an accreditation body (NVAO) that accredits ITET to ensure its quality and relevance.

In Norway, national regulations define the formal qualification requirements for VET teachers. Moreover, they stipulate that universities and university colleges need to have an internal quality assurance system. In addition, there is a professionally independent agency, the Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education, under the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research that supervises the quality development of the country’s higher education institutions, which provide ITET.

Co-ordinating between VET institutions and teacher-training institutions for better design and delivery of VET teacher training

The co-ordination between VET institutions and teacher-training institutions is important in many aspects for the quality of ITET. When designing and delivering ITET, the learning needs of the teacher candidates and the training needs of the VET institution that would eventually hire those candidates need to be taken into account. Teacher-training providers can better keep the ITET curriculum for VET teachers up to date when they collaborate with VET institutions, and together develop research and innovation in pedagogical approaches (OECD, 2021[1]). As described above, in Canada universities collaborate with VET providers to design and deliver ITET. Moreover, in the cases of teacher-training programmes that have an element of practical training in a VET institution, guidance and supervision both from the VET institution and the teacher-training institutions should be well coordinated.

Such collaboration exists in the Netherlands, for example. VET institutions assess candidates for lateral entry into the VET teaching profession for their competency and professional strength. This assessment is the main source to define the specific learning needs to be addressed by teacher training programmes offered by the universities of applied sciences (UAS). The UASs accommodate the different needs of both the VET institution and the candidates. That is, the VET institution- the future employer- assesses the skills and training needs of the candidate, and then based on this assessment, the UAS develops a personalised training programme for this candidate.

In Norway, VET teachers can participate in an exchange programme with trainers whereby VET teachers are sent to enterprises to have a better understanding of how on-the-job training works, and training supervisors and trainers are sent to schools to familiarise themselves with school-based VET (Haukås and Skjervheim, 2018[23]). Although this is not part of ITET, this helps improve the collaboration between VET teachers and trainers as well as the broader cooperation between schools and companies.

1.3.4. Initial preparation for in-company trainers

Providing accessible and flexible training options

Training for in-company trainers comes in many shapes and forms. In all of the five countries analysed in this report, training for trainers is optional rather than mandatory. Even in Germany, where trainers are required to pass a specific examination to be a qualified training, the training to prepare for this is optional and eligible individuals can take the trainer aptitude examination without taking these courses.

Available training programmes are mostly non-formal, delivered by a variety of institutions. In Canada, provincial and territorial apprenticeship authorities, apprentice employers, industry associations as well as universities provide workshops or guidelines for in-company trainers. The training courses for trainers in Germany are usually offered by the chambers of commerce and crafts but also by universities of applied sciences. In Denmark, trainers can participate on a voluntary basis in adult vocational training courses. In the Netherlands, the Organisation for the Cooperation between VET and the Labour Market (SBB) offers free training courses and support for in-company trainers in taking these courses and in better organising their workplace training. In Norway, the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training offers resources together with sub-national entities and private sector stakeholders.

As participants in such training programmes are usually in employment, flexibility in delivery is key to enable and encourage participation. In Germany, the preparatory training programmes for the aptitude examination are offered in a flexible way – e.g. in different learning formats, lengths and intensities. Quebec (Canada) has university-offered certificate courses for in-company trainers that are delivered on a part-time basis and offered on weekends or in the evening. The SBB training courses provided in the Netherlands have online components. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training offers free online resources for apprentice trainers, which include lectures and short movies showing how instruction can be carried out in practice. Together with this, county municipalities, training offices, university colleges, and some enterprises provide optional courses or practice-oriented online courses for training supervisors and in-company trainers.

Some countries provide financial support to facilitate and encourage training participation. In Denmark, the adult vocational training courses are partially publicly funded and subsidies for course participation are available. In the Netherlands and Norway, the training resources described above are free of charge. In Germany, employers of the trainers often pay their training course and examination costs and federal funding programmes are in place for prospective in-company trainers or their employers.

Providing relevant and high-quality training

In-company trainers should be equipped with vocational and pedagogical skills, knowledge about the workplace and the occupation, and the skills to co-ordinate with the provider of school-based VET. Available training programmes aim to train prospective trainers in these areas.

In Canada, training for in-company trainers is designed to learn about the entire process of apprenticeships, trainers’ duties and best practices, basic concepts and principles of work-based learning, and efficient mentoring for apprentices. In Denmark, adult vocational training courses prepare trainers for their role, providing training on various aspects of apprenticeship, including, how to organise and provide work-based training, motivate students and ensure quality of the training. In Germany, courses that prepare for the trainer aptitude examination can be tailored to the existing skills of the candidate. These courses focus on the competences that are tested by the trainer aptitude examination: checking training requirements, planning and preparing training, assisting in the recruitment of trainees, and conducting and completing training. In the Netherlands, SBB courses provide a mix of theory and practical tips for trainers as well as online and offline tools such as e-learning or webinars to learn about supervising VET students, discussion on practical learning with SBB advisors on work placement, workshops aimed at beginner practical trainers, and an online portal that provides comprehensive advice, information and guidance for trainers.

As the landscape of training for trainers is highly diverse, with training taking many forms and delivered by a variety of providers, quality assurance is essential to ensure a certain level of quality and to make the offer transparent to prospective trainers. Different from the other countries, Germany has regulations on the qualification and training of in-company trainers: the Ordinance on Trainer Aptitude governs the trainer training and qualification. In 2009 an advisory committee under the direction of the BIBB created a modernised framework plan, in order to ensure that quality standards of training for trainers are uniform across the federal states and that prospective trainers are better prepared for their future duties. Germany continues to improve its trainer examination frameworks and the corresponding training mechanisms. Following a BIBB study that examined those frameworks and mechanisms in 2020/21, in particular against the emerging trends such as digitalisation and environmental sustainability, efforts are underway to complement the examination with further training and refresher courses and concretise content in line with the current challenges (Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (BIBB), 2021[24]).

In Denmark, various actors contribute to development and quality assurance of adult vocational training (AMU) courses for trainers. The Ministry of Education approves new training programmes, social partners are responsible for developing AMU courses and associated tests in line with skill needs and advise from the Ministry. The Danish Agency for Education and Quality ensures the programmes comply with the applicable rules and oversees the AMU providers.

Entry requirements help ensure that VET teachers hold the necessary skills and knowledge, and these requirements need to be transparent and clear. At the same time, flexibility is needed, so that individuals with relevant skills and knowledge can enter the profession even when they do not (yet) fulfil all requirements.

Prospective or new VET teachers need to be able to enrol in high-quality ITET that allows them to develop the right set of skills. These ITET opportunities need to be easy to access, and should therefore be organised in a flexible way and coupled with targeted financial support.

Allowing the providers of ITET for VET teachers to have a certain autonomy over how they organise and deliver training can help ensure that the training fits the needs of their learners. Such autonomy should be supported by a solid quality assurance mechanism.

Coordinating between VET institutions and teacher-training institutions contributes to a better design and delivery of VET teacher training. This includes partnering for the development of subject-specific skills and knowledge, as well as collaborating to provide opportunities for aspiring VET teachers to put their teaching skills into practice in a VET institution.

Equipping in-company trainers with pedagogical skills will support them in transferring their knowledge and skills and supporting the learning journey of the learner. Flexible pedagogical training and materials should therefore be made available, and when such training is optional incentives need to be provided to encourage trainers and their employers to take up the training. Moreover, training should be provided on all relevant aspects of in-company training - from the start to completion of work-based learning.

Regulations on the quality of work-based learning can also foster the quality of the trainers. Such regulations takes a more holistic approach to achieving high-quality training at the workplace, while possibly also allowing for more flexibility than when strict qualification or skills requirements are imposed on in-company trainers.

References

[10] Advance CTE & CCSSO (2016), The State of Career Technical Education: Increasing Access to Industry Experts in High Schools, https://cte.careertech.org/sites/default/files/files/resources/State_of_CTE_Industry_Experts_2016_0.pdf.

[8] BIBB (2015), COMPENDIUM: Quality of in-company vocational education and training, https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/compendium_quality-vet_en.pdf.

[24] Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung (BIBB) (2021), Projekt 2.2.355: Kurzstudie zur Prüfung des Evaluierungsbedarfs der AEVO.

[18] Cedefop (2019), Cedefop European database on apprenticeship schemes, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/data-visualisations/apprenticeship-schemes/country-fiches.

[9] Cedefop (2019), Vocational education and training in Europe - Germany, https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/vet-in-europe/systems/germany-2019.

[15] CentERdata (2021), De toekomstige arbeidsmarkt voor onderwijspersoneel: po, vo en mbo 2021-2031, https://www.voion.nl/media/4088/toekomstige-arbeidsmarkt-onderwijspersoneel-po-vo-mbo-1.pdf.

[12] Dohmen, D. and M. Thomsen (2018), Prognose der Schüler*innenzahl und des Lehrkräftebedarfs an berufsbildenden Schulen in den Ländern bis 2030 [Forecast of the number of pupils and the need for teachers in vocational schools in the federal states up to 2030], GEW, https://www.gew.de/fileadmin/media/publikationen/hv/GEW/GEW-Stiftungen/MTS_-_Gefoerderte_Projekte/2018-11_Prognose_Schuelerzahl_Lehrkraeftebedarf_BB-Schulen.pdf.

[4] European Commission (2022), ESCO database - Occupations: Hairdressing vocational teacher, http://data.europa.eu/esco/occupation/93f61216-b9c8-4051-bb1e-32839c1566c1.

[5] European Commission (2022), ESCO database - Occupations: Business administration vocational teachers, http://data.europa.eu/esco/occupation/3db35c88-bcb7-4de4-914a-9a9839a3c911.

[6] European Commission (2022), ESCO database - Occupations: Corporate trainer, http://data.europa.eu/esco/occupation/0ba06640-e0ac-4911-9e43-289a8e41651e.

[17] Eurostat (2021), European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/labour-force-survey.

[23] Haukås, M. and K. Skjervheim (2018), Vocational education and training in Europe - Norway.

[7] Hensen, K. and U. Hippach-Schneider (2016), Supporting teachers and trainers for successful reforms and quality of vocational education and training: mapping their professional development in the EU - Germany, Cedefop ReferNet thematic perspectives series.

[21] Hoeckel, K., S. Field and W. Grubb (2009), A Learning for Jobs Review of Switzerland 2009, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264113985-en.

[16] Huismann, A. and U. Hippach-Schneider (2021), Teachers’ and Trainers’ professional development to support inclusive and sustainable learning: Germany, Cedefop ReferNet thematic perspectives series.

[2] Jeon, S. (2019), Unlocking the Potential of Migrants: Cross-country Analysis, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/045be9b0-en.

[11] KMK (2019), Compact data on education, https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/pdf/Statistik/KMK_Statistik_Folder_2019_en_RZ_web.pdf.

[20] Ministry of Education and Research of Estonia (2017), Background Report for OECD on Vocational Education and Training.

[14] OCW (2020), Staff in MBO, https://www.ocwincijfers.nl/sectoren/middelbaar-beroepsonderwijs/personeel.

[1] OECD (2021), Teachers and Leaders in Vocational Education and Training, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/59d4fbb1-en.

[3] OECD (2020), Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

[22] OECD (2010), Learning for Jobs, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264087460-en.

[13] Skolverket (2019), Lärarprognos 2019, https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=5394.

[19] WKO (2019), In-company trainers, https://www.wko.at/service/bildung-lehre/Ausbilder.html.

Note

← 1. ESCO distinguishes essential and optional knowledge, skills and competences in occupational profiles. "Essential" are those knowledge, skills and competences that are usually required when working in an occupation, independent of the work context or the employer. These are different from essential skills terminology that is used in countries like the United Kingdom.