Portugal

This country profile features selected environmental indicators from the OECD Core Set, building on harmonised datasets available on OECD.stat. The indicators reflect major environmental issues, including climate, air quality, freshwater resources, waste and the circular economy, biodiversity, and selected policy responses to these issues. Differences with national data sources can occur due to delays in data treatment and publication, or due to different national definitions and measurement methods. The OECD is working with countries and other international organisations to further improve the indicators and the underlying data. The text of this country profile is drawn from the OECD Environmental Performance Review of Portugal 2023.

Portugal is the westernmost country of mainland Europe. It also includes the Azores and Madeira archipelagos in the Atlantic Ocean. Its territory covers 92 200 km2 and includes 2 600 km of coastline. Agricultural land and forests each cover about 40% of its land area.

The Portuguese economy is small and open. In 2021, Gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was 25% lower than the OECD average. Economic activity grew steadily from 2013 until the COVID-19 pandemic. GDP rose by 4.9% in 2021, rebounding from an unprecedented slump in 2020 (-8.4%). The services sector, in particular tourism, is the country’s largest employer, having overtaken the traditionally predominant manufacturing and agriculture sectors.

Population density is similar to the OECD Europe average but distribution across regions is uneven. Density is higher along the western and south coastlines, as well as in the urban areas of Lisbon and Porto where it can exceed 1 000 inhabitants/km2. The demographic decline in rural areas and the fragmentation of private land ownership is a challenge for sustainable forest management, fire prevention and biodiversity protection.

Portugal possesses a diverse natural heritage thanks to its geographical location and geophysical conditions. The Azores and Madeira archipelagos are home to unique habitats. On the mainland, the dune habitats, rocky cliffs, marshes in estuary and lagoon systems are all important as well. Numerous bird populations shelter in estuaries. The Madeira Archipelago hosts some of the most significant seabird colonies in the North Atlantic. Portugal’s mineral resources include significant deposits of zinc, copper, lead, tin and tungsten, as well as lithium. The country relies entirely on imports for fossil fuels. Domestic energy production comes primarily from bioenergy, wind and hydro power.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (excluding land use, land use change and forestry [LULUCF]) declined due to the reduction in energy demand following the 2008 crisis and increasing renewable electricity generation. With the economic recovery, emissions rebounded in 2014-17, particularly in the transport sector. They have since fallen, driven by a strong shift away from coal-fired power generation. In 2020, the reduction in GHG emissions can be partly attributed to lower energy consumption due to restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. The LULUCF sector is a net sink. It was a net emitter in 2003, 2005 and 2017 due to big forest fires.

The transport sector is the largest GHG emitter, followed by energy industries and manufacturing industries and construction. Over 2005-20, emissions have decreased in all sectors but agriculture.

Portugal’s economy is less CO2 intensive than the OECD Europe average, reflecting a service-oriented economy and a high share of renewable energy. However, emissions of methane (from agriculture and waste) and fluorinated gas (hydrofluorocarbons from refrigeration and air conditioning equipment) make its economy more GHG intensive than the OECD Europe average. As most OECD countries, Portugal’s demand-based CO2 emissions (including emissions incorporated in imported goods) are slightly above production-based emissions.

Portugal’s energy mix remains dominated by fossil fuel but renewables account for a higher share than in most OECD countries. Over the past decade, there has been a shift from oil and coal to natural gas and renewables. The share of renewables has increased steadily over the last two decades, mainly driven by the expansion of wind generation and more recently growing solar photovoltaic generation. Biomass used in industry and residential building heating remains the largest source of renewable energy. The renewable energy supply varies significantly with annual variations in hydropower generation. In 2021, the last two coal power plants were closed. Portugal relies entirely on imported fossil fuels but imports from the Russian Federation represent a relatively small share of its total energy supply.

Portugal met its 2020 emission reduction objectives under the Gothenburg Protocol for sulphur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOC) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) but not for ammonia (NH3).

Combustion for domestic heating is a major source of PM2.5 emissions while combustion in manufacturing industries dominates SOx emissions. Road transport is the main emitter of NOx and NMVOC emissions mainly come from solvent use. Emissions of major air pollutants have decreased due to the shift in electricity production from coal to natural gas and renewable energy, the implementation of new desulphurization systems in large energy plants and stricter vehicle emissions standards. However, reductions have slowed down in the years preceding the COVID-19 crisis and NH3 emissions have grown with the number of poultry.

Emission reductions went on par with air quality improvements. In Portugal, the average population exposure to PM2.5 is well below the OECD average. In all regions but Madeira, it is nevertheless above the new guideline value of 5 µ/m3 recommended by the World Health Organization. Air quality remains a concern with regard to concentrations of nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter in urban areas and tropospheric ozone in rural areas.

Portugal’s freshwater resources are above the European average, resulting in low water stress at the national level. However, seasonal and spatial distribution of freshwater resources and use varies widely. Agriculture accounts for the bulk of freshwater abstractions. Agricultural water withdrawals have increased by about 25% since the mid-2010s, particularly in the southern regions where water scarcity is a concern. Per capita water abstraction for public supply peaked in 2005 but has since stabilized to a level close to the OECD average.

Connection rates to public wastewater treatment plants have significantly increased in the past decades. In 2017, 86% of the population was connected to public wastewater treatment plants, with more than a third benefitting from tertiary (advanced) treatment.

The amount of municipal waste generated per capita in Portugal remains below the OECD average, but above the OECD Europe one. Generation of municipal waste declined in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis, but has been increasing again since 2013, along with the economic recovery.

Recycling and composting have significantly increased due to the implementation of the EU Waste Framework Directive and the various national policy instruments and strategic plans for the management of municipal waste, which have guided and defined targets in the production and management of this type of waste. However, landfilling remains the main treatment method and Portugal has one of the highest landfilling rates among the OECD countries.

Material productivity has improved until 2013 and remained broadly constant since then, and is low compared to both OECD and OECD-Europe levels. Domestic material consumption (DMC) decreased significantly in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis, and has remained stable since 2017. The material footprint steadily decreased, though at a slower pace since 2013.

As in many OECD countries, non-metallic minerals account for the largest share of DMC, driven by construction materials. The share of metals and fossil energy materials has decreased while that of biomass has globally remained constant. Fossil energy materials account for a smaller share of DMC than in most other OECD countries as Portugal makes greater use of renewable energy.

In contrast to the previous decade, agricultural land has increased slightly since 2010, with a decline in grassland offset by an increase in cropland (INE, 2020). Forest area remained stable, while artificial land continued to grow, albeit at a slower rate than before.

About 3 600 species of plants occur in Portugal, as well as 69 taxa of terrestrial mammals, a total of 313 bird species, and 17 amphibian and 34 reptile species. Agriculture, infrastructure development, invasive species, natural processes (such as erosion), climate change and fires are exerting major pressures to biodiversity. About 30% of fish and birds and 20% of mammals and reptiles are threatened.

According to the Court of Audit, in 2020, protected areas covered 25% of Portugal’s territory and 8.9% of marine areas under its jurisdiction. The country thus met the 2020 Aichi target of protecting at least 17% of land area but missed the target of protecting 10% of coastal and marine areas. Management plans have been developed only for a few Sites of Community Importance in the Natura 2000 network.

In real terms, revenue from environmentally related taxes decreased in the early 2010’s with declining economic activity. It then rose over 2013-19 due to higher consumption and taxes on diesel, before falling with the COVID-19 crisis which led to a decline in the purchase and use of cars. It remains however above the OECD and OECD Europe averages. As in many countries, most receipts come from taxes on energy products and, to a lower extent, on motor vehicles’ purchase and use. Taxes on pollution and resource management such as the tax on effluent discharges and fees for hunting and fishery license raise little revenue.

In 2021, net effective carbon rates (NECR) in Portugal consisted of fuel excise taxes and to a smaller extent of carbon taxes and of permit prices from the EU-ETS. Portugal priced about 74% of its GHG emissions and about 28% were priced at an ECR above EUR 60 per tonne of CO2. Emissions priced at this level originated primarily from the road transport sector. The majority of unpriced emissions were non-CO2 emissions.

Portugal implicitly supports fossil fuels consumption through tax expenditure. Oil and gas attract the bulk of government support. The largest amounts include reduced tax rates for diesel fuel used by agricultural equipment and (since 2017) partial refund of diesel taxes to freight companies; tax exemptions on energy products used for electricity production and co-generation or by industrial installations under the ETS or an energy-efficiency agreement. Since 2014, foregone revenue from tax reliefs has increased with consumption and taxes on diesel and natural gas. In 2018, Portugal started to gradually phase out some fuel and carbon tax exemptions, which helped to phase out coal power in 2021.

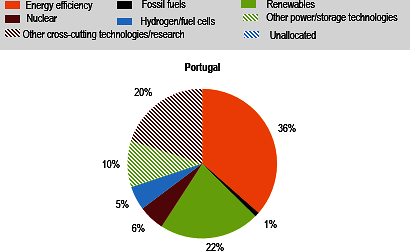

The country is considered as a “moderate innovator” in the European Eco-Innovation Scoreboard. This is due to low government spending on R&D in environmental and energy fields and limited patenting activity, although Portugal holds a relative advantage in terms of technologies for climate adaptation. Public budget on energy R&D is mostly allocated to energy efficiency, renewable energy and cross-cutting technologies.

The share of environment-related patents in total patents has fluctuated but generally decreased since the aftermath of the 2009 economic crisis. It is now below the OECD and OECD-Europe averages. Most patents are filed for climate change mitigation although since 2018, the number of general environmental management patents (e.g. air and water pollution control) significantly increased.

The level of official development assistance (ODA) fell considerably during the 2010-2014 debt crisis as part of fiscal consolidation efforts and have since remained stable, albeit at low levels. The ODA budget cuts mainly affected support to climate change mitigation and environment-related activities. ODA on climate mitigation has plunged. In 2020, Portugal committed 7.4% of its total bilateral allocable aid in support of the environment and the Rio Conventions (the DAC country average was 38.8%), down from 12.2% in 2019. Three percent of screened bilateral allocable aid in 2020 focused on environmental issues as a principal objective, compared with the DAC country average of 10.8%. Two percent of total bilateral allocable aid focused on climate change overall, down from 3.2% in 2019 (the DAC country average was 34%). Portugal had a greater focus on adaptation (1.3%) than on mitigation (0.5%) in 2020.

References and further reading

Agência Portuguesa do Ambiente (APA) (2022), National Informative Inventory Report 2022, Submitted under the NEC Directive (EU) 2016/2284 and the UNECE Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution, 15 April, Portuguese Environmental Agency, Amadora, https://cdr.eionet.europa.eu/pt/eu/nec_revised/iir/envyk8r3a/IIR2022_15april.pdf.

APA (2022), provisional version of the third RBMPs 2022-27, https://participa.pt/.

APA (2021), State of the Environment Report 2020/21, Portuguese Environmental Agency, Amadora, https://sniambgeoviewer.apambiente.pt/GeoDocs/geoportaldocs/rea/REA2020/REA2020.pdf.

ICNF (2020), Sixth National Report for the Convention on Biological Diversity - Portugal, The Clearing-House Mechanism of the Convention on Biological Diversity, https://chm.cbd.int/database/record?documentID=253132.

IEA (2021), Portugal 2021 Energy Policy Review, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3b485e25-en.

INE (2022), Environmentally related taxes and fees, www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=539419621&DESTAQUESmodo=2.

INE (2020), Land use land cover statistics, https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=435669204&DESTAQUESmodo=2

OECD (2023), OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Portugal 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d9783cbf-en.

OECD (2022), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2022 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/f6da2159-en.

OECD (2022), Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Turning Climate Targets into Climate Action, OECD Series on Carbon Pricing and Energy Taxation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e9778969-en.

OECD (2022), "Portugal", in Development Co-operation Profiles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/12c61cf7-en.

OECD (2020), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/959.

Tribunal de Contas (2022), Auditoria às Áreas Protegidas [Audit of Protected Areas], Tribunal de Contas, Lisbon, www.tcontas.pt/pt-pt/MenuSecundario/Noticias/Pages/n20220811-1.aspx.