Chapter 3. Digital transformation for youth employment and Agenda 2063 in Southern Africa

This chapter examines the relationship between digitalisation and youth employment in the countries of Southern Africa (Angola, Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe). The first two sections assess digital development across two groups: countries in the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and non-SACU countries. They highlight problems that the countries face in using digitalisation to address challenges of youth employment.

The last three sections discuss public policies that can help create more and better jobs through digitalisation in Southern Africa. The first of these sections considers measures to ensure equitable and affordable access to communications infrastructure. The second examines public policies to prepare the workforce for future skill demands. The last section reviews interventions that can build an integrated digital economy in the region and enhance strategic regional value chains with digitalisation.

Southern Africa is witnessing a two-speed digital transformation. In countries of the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) − Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa – the latter is leading the digital transformation which could potentially lower persistently high unemployment rates. However, current barriers in infrastructure, skills and affordability are likely to widen the digital divide. The richest 40% of the population are twice as likely to have access to the Internet as the poorest 40%.

In contrast, non-SACU countries − Angola, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe − remain at early stages of digitalisation with only 25% of the population having access to the Internet. Weak infrastructure and poor educational outcomes are preventing the large pool of informal workers from adopting and benefiting from digital technologies.

The region will need to address these challenges by focusing on three policy levers:

Developing reliable and affordable communications infrastructure beyond urban centres. Currently, only 22.6% of the region’s population can afford one gigabyte of prepaid mobile data. Effective regulations are key to attract private investment, while proactive public interventions may be necessary to ensure universal and affordable access.

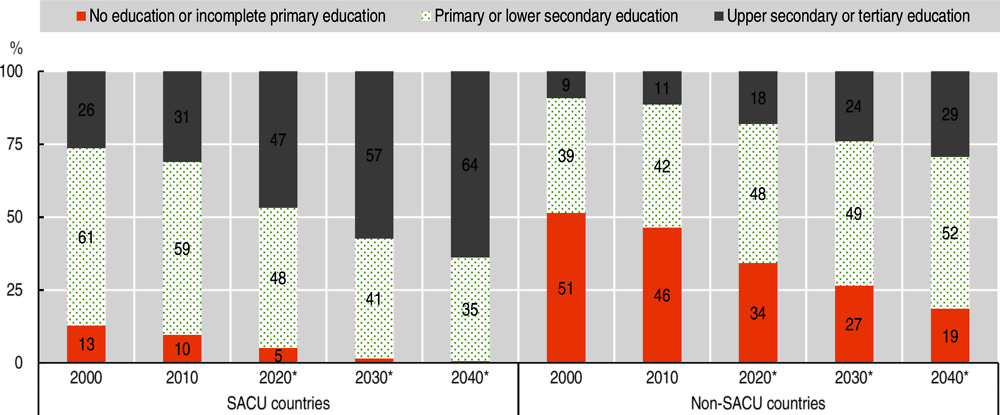

Expanding the provision and quality of education and promoting lifelong learning to meet future skills demand. Under a business-as-usual scenario, the share of youth with an upper secondary or tertiary education is expected to increase from 27.8% in 2020 to 38.2% in 2040.

Accelerating the implementation of existing regional initiatives. Since 2012, Southern African Development Community countries have adopted 29 different initiatives related to ICT regulation. The regional industrialisation strategy also needs to embrace the digital transformation of strategic value chains.

Digitalisation could help governments tackle high unemployment

SACU countries face persistently high unemployment. The unemployment rates in these countries have remained at over 15% since the 1990s (AUC/OECD, 2018). Most of the employed are waged employees in the formal sector (ranging from 85% in South Africa to 43% in Lesotho), while informal employment is relatively limited. In these five countries, the services sector accounts for the largest share of employment (ranging from 71% in South Africa to 46% in Lesotho). South Africa stands out for its low rate of entrepreneurship and high rate of structural unemployment. Today, COVID-19 is a major threat to the job market in South Africa: empirical research estimates a 40% decline in active employment in 2020, half of which is job terminations, thus suggesting persistent labour market effects of the crisis (Zizzamia et al., 2020).

Digitalisation offers opportunities for direct job creation in the region. An example of this is the jobs that the growing information and communications technology (ICT) sector is directly creating in the telecommunications and broadcasting sectors. Over the period 2015-19, employment in these two sectors has increased, by 2.2% and 1.8%, respectively (ICASA, 2020). In South Africa, the shift towards services sectors caused by digitalisation is responsible for most of the country’s employment growth in recent years; notably, between 2000 and 2019, the financial and community services sectors accounted for over half of the increase in employment (Aslam, Bhorat and Page, 2020). However, the jobs that digital technology companies create are mostly for better-educated workers and entrepreneurs.

Digitalisation can also indirectly create new jobs – including jobs for youth and female workers – by boosting productivity and offering new business models. Klonner and Nolen (2010) found that mobile phone coverage in South Africa has increased wage employment by 15 percentage points. This is mostly due to the increased employment of women. Digitalisation also enables new business models to emerge, such as those in the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) sector. The sector created 13 733 new jobs in South Africa in 2019. Youth workers account for 87% of these new jobs, while female workers account for 65% of them. The majority of BPO jobs (86%) are voice-based − frontline customer services, sales and lifecycle management, while a small proportion (16%) are in non-voice jobs such as back-office processing, finance and accounting, and information technology (IT) outsourcing (BPESA, 2019).

At the same time, digitalisation poses new threats to jobs:

Automation may accelerate the process of de-industrialisation and reduce the demand for formal sector jobs in the region. In South Africa, for instance, one in three jobs could be at risk of complete automation. In the automotive sector, one of the most dynamic sectors in the country, 87% of job losses result from the growing efficiency of factories through automation and enhanced technology (Chigbu and Nekhwevha, 2020). With the COVID-19 crisis expected to accelerate the global adoption of robots in the manufacturing sector (see Chapter 1), this risk could increase unemployment and displace more jobs.

There are risks associated with low-quality employment on digital platforms. The numbers of gig workers (i.e. those active on digital platforms like Uber, SweepSouth and other free social media) are rising, especially in South Africa. Gig workers represent at least 1% of the South African workforce; as their numbers are growing by well above 10% yearly, they could be in the millions in the next decades (Fairwork Foundation, 2020). The increasing social and economic importance of these independent workers collides with their non-standard employment status, which can prove particularly challenging especially in times of crisis.

Despite these risks, emerging evidence suggests that digitalisation could be a net job creator in the region. For South Africa, McKinsey & Company estimate that although 3.3 million jobs are expected to be displaced due to increased digitalisation and automation, digital technologies could also create 1.2 million direct jobs in new ICT occupations. They project that another 3.3 million will be indirectly created thanks to digitalisation (McKinsey & Company, 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic motivated governments to accelerate Africa’s digital transformation. During the COVID-19 crisis, the South African government has provided a special Social Relief of Distress grant requiring a simple registration through WhatsApp or alternative channels for workers receiving no other official social grants (Fairwork Foundation, 2020). To continue educational activities during COVID-19 lockdowns, the ministries of education in Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe have offered e-learning resources for use by students and teachers (UNESCO, 2020). The Central Bank of Lesotho has negotiated fee reductions and has relaxed transaction limits to encourage the use of mobile money.

Prior to the crisis, governments in the region had begun using digital technologies to increase the efficiency and transparency of their governance systems. Box 3.1 gives several examples of e-governance initiatives in South Africa.

Over the last two decades, the South African government has taken numerous steps to promote e-government in the country. Several programmes have proved relatively successful:

In 2001, the South African Revenue Service (SARS) introduced an electronic tax filing and payment system in accordance with the government’s broader e-government strategy for public services. For the fiscal year 2018/19, SARS received 4 886 360 personal income tax returns. Of this total, 2 667 667, or 55%, were submitted electronically.

The Khanya Project is an initiative of the Western Cape province of South Africa. Its objective is to use technology to enhance teaching and learning at foundation, primary and secondary school levels. The pilot project was launched in 2006 in five schools, where interactive whiteboards were used for different grades and subjects. By the end of July 2011, 90% of the 1 570 government schools in the Western Cape had acquired computer technology, with a total of 46 120 computers in use.

The Health Patient Registration System (HPRS) project aimed to create a patient and service provider electronic registration system as part of the National e-Health Strategy 2012-2016. At the end of 2017/18, 2 968 healthcare facilities were using HPRS, and over 20 million people were registered in the system. This has significantly improved and standardised data collection as well as lightened the data capturing workload at the facility level.

Sources: Genesis Analytics (2019a), Evaluation of Phase 1 Implementation of Interventions in the National Health Insurance (NHI) Pilot Districts in South Africa; South African Revenue Service (2018), SARS Annual Report 2018/19; SMART (2011), “Western Cape Education Department, South Africa: Khanya Technology in Education Project”.

SACU countries benefit from the rapid expansion of communications infrastructure but face a widening digital divide

The region has invested considerably in first-mile communications infrastructure that link SACU countries to the global Internet. A network of submarine cables and cross-border terrestrial links connect all Southern African countries to the Internet. As of 2020, South Africa has six operational submarine cable connections, and others are planned. However, the stability of these cables remains a concern due to repeated outages and disruptions (Browdie, 2020). By 2024, the 2Africa cable should improve the reliability of Internet connections, as it will be sunk 50% deeper than existing cables. Landlocked countries have managed to increase their connections to submarine cables through timely investments. For instance, Lesotho’s overall international bandwidth capacity grew by nearly 36% between 2018 and 2020. Nonetheless, challenges remain to lower transit costs between countries’ borders and submarine cable landing station and to meet growth in data consumption.

Southern Africa has a relatively advanced middle-mile Internet infrastructure that expands the connection to most intermediary and large population centres. The fibre-optic network covers 71% of the population in intermediary cities (between 10 000 and 500 000 inhabitants) in Southern Africa, the highest rate in Africa (see Chapter 2). This network is more prevalent in big cities, where it covers 79% of the population. All SACU countries, except Namibia, have at least one active Internet exchange point (IXP) that facilitates domestic Internet traffic.1

Last-mile infrastructure connecting the Internet to end-users has expanded in the past decade, largely due to the expansion of high-speed mobile Internet. The fourth generation (4G) network covered 71% of the population in Southern African countries in 2019, up from only 5.1% in 2012 and above Africa’s average of 60%. That said, the share of the population with Internet access in SACU countries is considerably higher than the share in Southern Africa’s non-SACU countries. Similarly, the 4G mobile network has a higher coverage in SACU than in non-SACU countries (Figure 3.1).

South Africa, in particular, has built one of the most advanced communications infrastructure on the continent with the support of large private investments. Large investments from Telkom, Liquid Telecom South Africa, Broadband InfraCo, municipal providers and mobile network operators such as MTN and Vodacom have improved network capabilities. South Africa is expected to be one of the first countries in Africa to launch commercial 5G services, following ongoing investments from Rain, Vodacom and MTN. In 2020, Liquid Telecom began offering a wholesale 5G service using its 3.5 gigahertz concession (Lancaster, 2020).

Despite the progress in improving both coverage and the quality of communications infrastructure, governments need to increase access to digital technologies, especially among the most disadvantaged populations (Figure 3.2). Lack of appropriate digital skills and literacy levels are significant barriers to digital inclusion, as reflected by the gap in Internet access across education levels. Similarly, the population belonging to the top 40% income group are twice as likely to have access to the Internet as the poorest 40%. The inequalities in digital adoption could exacerbate existing socioeconomic inequalities, and Southern Africa is home to six of the world’s top ten unequal countries (AUC/OECD, 2018). SACU countries need to develop policies that promote access to the last mile services to begin reaping the benefits of digital infrastructure development.

The low level of 4G uptake, despite its rapid rollout, shows that the region should give greater consideration to demand for mobile technology adoption than supply. In South Africa, for instance, while 90% of the population benefit from 4G coverage, less than 30% have adopted it (GSMA, 2019). Surveys on Internet usage among youth in the region reveal that demand-side challenges such as digital literacy, affordability of services and devices, limited access to electricity, and availability of locally relevant content and applications are some of the main obstacles to Internet uptake (RIA, 2017).

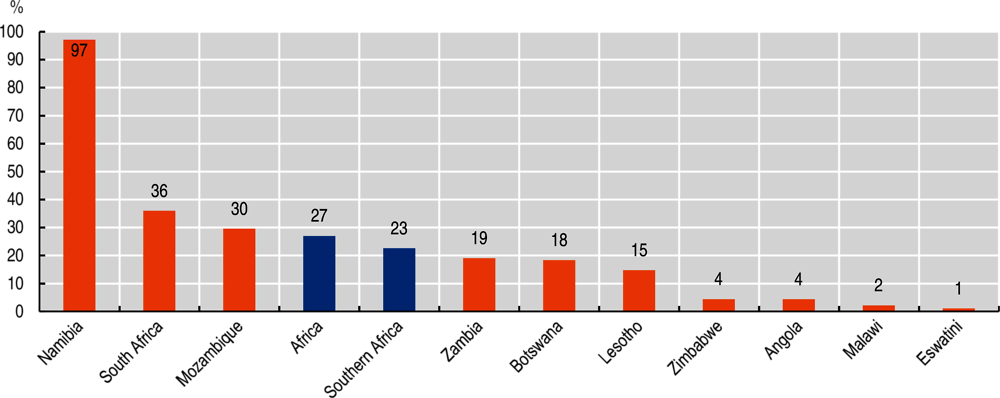

Affordability of mobile services is also a significant barrier to Internet use for a large share of the population. On average, only 22.6% of Southern Africans can afford one gigabyte (GB) of prepaid mobile data, the bandwidth needed to send or receive about 1 000 e-mails and browse the Internet for about 20 hours a month (Figure 3.3). Within countries, wide disparities exist between prices charged by service providers that dominate the market and those charged by the cheapest service providers. The most extreme difference is in South Africa, where the price charged by the dominant operator for a basket of services (USD 11.26) is almost 2.5 times that offered by the cheapest provider (USD 4.65) (Box 3.2).

South Africa leads the region’s digital economy, but broadening the digital transformation requires addressing the spatial divide and skill mismatches

South Africa provides the core of a dynamic digital economy in the region. The country is home to 700-1 200 active tech start-ups in multiple sectors. Start-ups in South Africa not only dominate in number, they are also often more advanced in terms of size and funding compared to their peers in the rest of Southern Africa. Table 3.2 shows further notable examples of digital start-ups in South Africa and other countries in the region. In Namibia, for instance, FABLab is adapting sensors for localised uses; its initial focus on environmental sensing may expand to water and waste management and to parking and transport management in the future.

The region’s digital trade activities are on the rise. Southern Africa’s annual e-commerce sales rose from USD 93.7 during the 2005-09 period to USD 155.3 million during the 2014-18 period, equivalent to an average of 3-5% of merchandise export values. Similarly, between 2005 and 2018, the value of the region’s digitally enabled services exports (e.g. insurance pensions, financial services) grew from USD 2.5 billion to USD 4.6 billion.

Venture capitalists and corporate investors have been instrumental in developing technology ecosystems in the region. Venture funds, development finance, corporate involvement and ever-growing innovative communities have contributed to their growth. Mobile operators and Internet providers, due to their close involvement in the digital space, have supported the majority of the tech hubs across the continent (GSMA, 2020b). The South African company MTN and communications infrastructure providers such as Liquid Telecom have launched in-house tech hubs in several markets on the continent and other supporting programmes for local entrepreneurs. Large tech companies are also strengthening the ecosystems by establishing a physical presence within tech hubs. In South Africa, for example, IBM collaborated with Wits University to set up a university-based incubator which promotes youth entrepreneurship and helps students develop the skills they will need for the digital economy by working with academia, corporates, government and entrepreneurs.

The capacity of the digital sector to multiply jobs has been limited to a few digital enclaves, or islands of excellence. Currently, jobs in ICT services (e.g. call centre work, coding, finance, accounting and legal support) are largely concentrated in South Africa’s major cities of Cape Town, Johannesburg and Durban; in 2017, only 4% of these jobs were located in other cities (Genesis Analytics, 2019b). Within the major cities, ICT services jobs are mostly found in business centres in affluent areas to which employees must travel from lower-income areas. The business centres enjoy excellent access to physical and digital infrastructure, skills and business partners but only employ small cliques of highly qualified technical experts.

Addressing the widening skill mismatch will be key to take advantage of digitalisation and tackle the threats of workforce displacements and automation. South Africa relies on a large pool of educated youth; 50% of its population achieve an upper-secondary or tertiary education up from only 28% in the early 2000s. Nonetheless, evidence from OECD (2017a) shows that, in 2015, 52.3% of South African workers were employed in occupations for which they did not have the correct qualifications, with 27.9% of them underqualified and 24.4% overqualified. In addition, as digitalisation is likely to induce a reallocation of the labour force in the coming years, especially of low-skilled workers, South African decision makers will need to take bold steps to sufficiently reskill displaced workers. McKinsey & Company (2019) estimate that, by 2030, the demand for workers with high educational attainment will increase by an additional 1.7 million employees. Thus, strengthening the education system to generate the skills needed at a sufficient scale will be vital.

The digital transformation offers opportunities for agricultural and informal workers

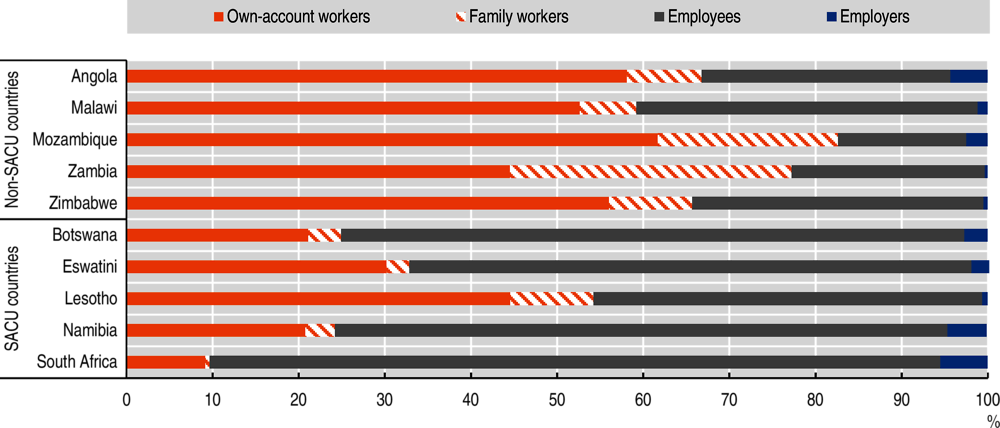

In Southern Africa’s non-SACU countries, the informal sector and agriculture absorb large shares of workers who cannot find employment in the formal sector, including in mining. Self-employment and family work dominate job creation in Mozambique (83%), Zambia (77%) and Angola (67%) (Figure 3.4). In Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe, the majority of the population still works in subsistence agriculture. In resource-dependent countries, such as Angola and Zambia, mining accounts for only 3.5% of employment despite contributing 14% to gross domestic product (GDP) (OECD/AUC, 2018).

While unemployment rates are lower in non-SACU than SACU countries, underemployment and working poverty remain pervasive in the former. As in many other sub-Saharan African countries, the magnitude of unemployment in non-SACU countries is masked by underemployment, as people work in low-quality or part-time jobs. Working poverty is therefore much higher in these countries. Over the 2010-19 period, more than 50% of workers lived in poverty in three of the five non-SACU countries: Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia. In comparison, only one in ten workers in Botswana, Namibia and South Africa received poverty-level wages over the same period (ILO, 2020).

Digitalisation offers the potential to transform the rural-urban value chains and empower agricultural workers. E-commerce platforms allow producers to reach a wider market and increase efficiency by eliminating trade intermediaries. New ways of generating, storing and sharing information on products and processes significantly improve the traceability of supply chains. Digital connectivity can also complement the creativity and knowledge of local actors by enabling them to engage in new niches. For example, in Zambia, the Maano Virtual Farmers’ Market is an e-commerce platform for listing and trading agricultural produce for farmers and international buyers. This system allows for greater transparency in negotiations and pricing and for more effective transactions. The application reached over 1 000 Zambian farmers with a total USD 50 000 worth of transactions during the pilot in May-October 2017 (FAO, 2018).

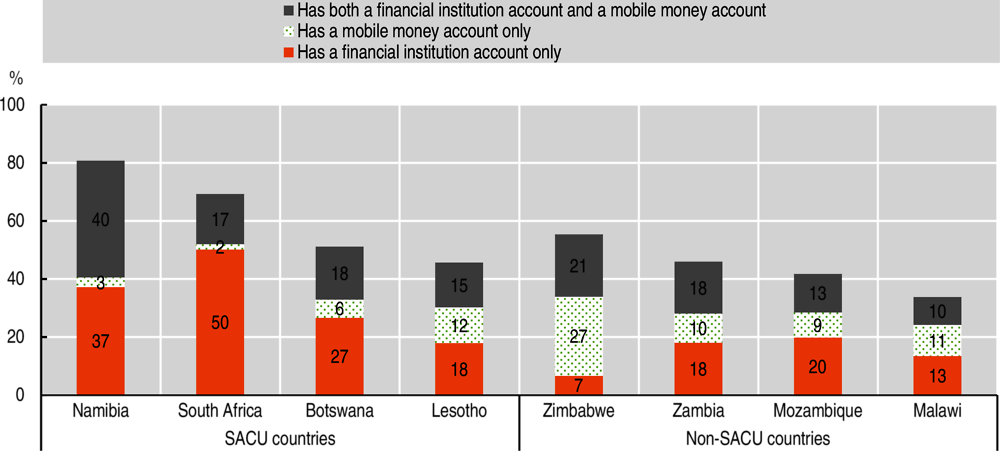

Technology-enabled financial services (fintech) offer a new range of products to informal actors, especially those in non-SACU countries with underdeveloped financial sectors. The use of mobile money services has contributed significantly to financial inclusion in non-SACU countries. In Zimbabwe, for instance, 27% of the population have only a mobile money account (see Figure 3.5). Mobile money has been instrumental in alleviating liquidity shortages, particularly a lack of access to hard currency, by giving a 24-hour option to deposit, withdraw or transfer money and to pay for goods and services, including electricity, from mobile phones (Fanta et al., 2016). During the COVID-19 crisis, Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia have encouraged mobile money use through fee waivers and through increasing transaction and balance limits.

Non-SACU countries are witnessing a rise in innovative business models and technology start-ups that feed into their nascent digital economy. In Zambia, the direct contribution of the ICT sector to GDP more than doubled between 2010 and 2018, from 1.6% to 4.4% (World Bank, 2020d). Tech start-ups offering innovative digital solutions are increasingly emerging in low-income countries. In Malawi, for instance, iMoSYs provides monitoring systems with access to reliable information for effective strategic decision making in a variety of sectors, such as water management, eHealth and industrial automation. Traditional corporations such as Standard Bank increasingly contribute to the digital economy by setting up incubators in several countries, including Angola and Mozambique. Large telecommunications companies are also stepping up. Liquid Telecom partnered with BongoHive in Zambia to offer high-speed Internet access and cloud-based services to entrepreneurs.

Weak infrastructure and low educational attainments pose challenges to the digital transformation in non-SACU countries

Access to both basic and communications infrastructure remains highly limited. Access to digital services and applications is mostly constrained by basic infrastructural issues. In most non-SACU countries, less than 40% of the population had access to electricity or benefited from 4G coverage in 2018. On average, only 25% of the population in non-SACU countries had access to the Internet, far below the SACU countries’ coverage, which reached almost 50% of the population, and Africa’s average of 34%. Worse yet, in Angola, despite relatively good coverage, mobile penetration has been declining since 2014 due to the combined effects of an economic slowdown and the lack of competition in the telecom market.

Internet speed in the region, especially in landlocked countries, is slow, though marginally increasing, and calls for regional policies on cross-border connectivity. In addition to unequal access to communications infrastructure, most Southern African countries have to deal with issues of Internet speed. It takes more than seven hours to download a 5 GB movie in Angola, Eswatini and Malawi. As a result, 36.5% of youth in Mozambique list the speed of Internet as a major constraint to Internet usage (RIA, 2018a). Additionally, landlocked countries, like Malawi, Zambia or Zimbabwe, face costs in expanding their telecommunications networks to an undersea Internet cable. A regional approach to facilitating cross-border connectivity will thus be essential to improve speed, affordability and overall digital inclusion in landlocked countries.

In non-SACU countries, poverty also prevents the local population from owning digital devices and accessing the Internet. In Mozambique, 76% of the surveyed population who have the opportunity to connect to the Internet in their area cannot afford Internet-enabled devices (RIA, 2018b). Similarly, in Angola, limited competition among mobile operators results in stagnated data prices (IFC, 2019). Ensuring affordability by removing all excise duties on feature and entry-level smartphones and strengthening competition through adequate regulations in the telecom sector would reduce Southern Africa’s digital divide.

Low levels of educational attainment limit the potential of non-SACU countries to benefit from the opportunities that new technologies offer. In these countries, only 18% of youth currently have an upper secondary or tertiary education, compared to 47% in SACU countries. Under a business-as-usual education scenario, the proportion of youth in non-SACU countries completing an upper-secondary or tertiary education could reach 29% by 2040 (compared to 64% in SACU countries; see Figure 3.6). This figure could reach 76% (233 million people) by 2040 if non-SACU countries can replicate Korea’s fast-track education scenario with more ambitious investments in education and health. For the moment, illiteracy rates are still high. In Mozambique, for example, illiteracy is 39%, and the rural population, particularly women, are the main victims (World Bank, 2019).

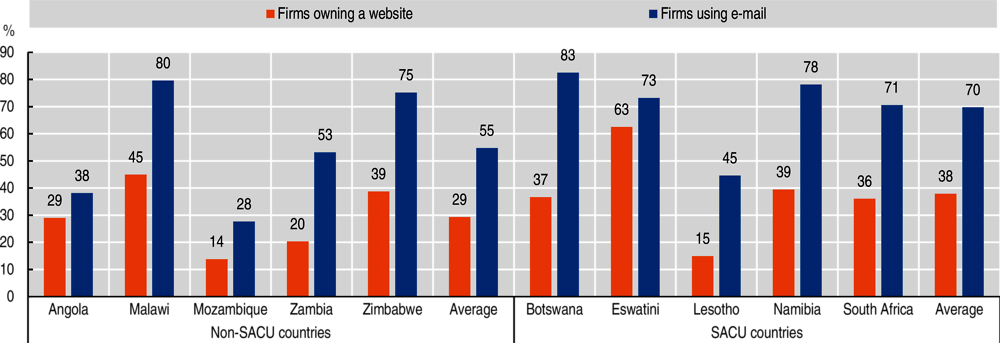

Digital adoption remains limited among Southern Africa’s firms, with insufficient skills being an important contributing factor. In non-SACU countries, only 29% of companies have a web presence, and 55% of companies employ the Internet to interact with their clients and customers, compared to 38% and 70%, respectively, in SACU countries (Figure 3.7). Such digital adoption is even less frequent among smaller firms. The shortage of skills lowers the likelihood of digital adoption among young entrepreneurs. Moreover, low digital literacy prevents them from efficiently using digital solutions that could assist them in their work. As the majority of firms in Southern Africa do not use the most basic tools of the Internet, strong and sustained government efforts are critical to encouraging digital adoption before promoting more sophisticated interventions.

Countries should support private investment in high-speed and affordable infrastructure

Southern African countries need to continue investing in basic and communications infrastructure. Despite increasing broadband coverage, the region’s communications infrastructure require considerable investment to ensure universal coverage and international competitiveness as technology evolves. For example, Alper and Miktus (2019) estimate that Southern Africa would need to invest USD 2.1 billion to reach full 4G coverage by 2025. In addition, the region needs to continue to increase the coverage and quality of electricity connections; 8.7% of formal manufacturing and services firms in the region cite electricity as the main constraint to doing business.

Attracting investment from the private sector and finding external sources of financing are vital to meeting this challenge. In the short to medium term, public resources in Southern Africa will be highly limited due to the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing economic crisis and to governments’ structural weakness in raising domestic revenues. Several non-SACU countries, such as Mozambique, Zambia and Zimbabwe, already faced debt distress before the COVID-19 crisis (see Chapter 8). The private sector has played a key role in providing technical expertise and financing communications infrastructure, investing approximately USD 2.5 billion a year over the 2015-19 period. In non-SACU countries, development partners’ assistance will also be crucial to finance infrastructure and support the implementation of digital policies. In Malawi, the World Bank invested USD 74.2 million in the Digital Malawi Program to improve access to digital technologies through four pillars: policy and legislation, digitalisation of public sector institutions, improved digital capacity, and project management (World Bank, 2017).

Effective regulations, notably through spectrum allocation policies (see Chapter 2), are critical to encouraging competition and investment among private telecommunications companies. Countries need to strengthen their regulatory capacities to ensure fair competition between operators. In Mozambique, a lack of transparency regarding spectrum allocation has created uncertainty around long-term investments in the mobile market (World Bank, 2019). Similarly, in Angola, lack of adequate equipment prevented fair frequency allowance, as the government was unable to identify free spectrum to release to operators (IFC, 2019).

Regulatory adjustments, especially in infrastructure sharing, can provide a sound foundation for deploying 5G in the region. In the short term, the 5G era is not imminent in most Southern African countries, as existing technologies such as 4G are enough to support the current demand for mobile Internet connectivity (GSMA, 2019). Nonetheless, arrangements to increase infrastructure sharing will be necessary to reduce the cost of densifying the transmission network needed to deploy 5G (OECD, 2019a). In Korea, for example, mobile operators hope to save around USD 933 million over the next decade by sharing their infrastructure for the 5G network (Telecompaper, 2018). In South Africa, the infrastructure sharing business is at a rudimentary stage. Out of 30 000 towers, only 10% are owned and operated by independent companies (Asif, 2019).

In certain cases, innovative public-private partnerships can help crowd in private investments. Cross-border public-private partnerships, for instance, can facilitate communications infrastructure development projects within a fragmented regional economic space and help landlocked countries benefit from regional economic growth (Baxter, 2020). Liquid Telecom became a key player in the development of the regional backbone network, expanding across 17 000 kilometres in Botswana, Lesotho, South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe with connections to Central and East Africa via the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Southern African countries can also learn from Rwanda’s successful partnership with Korea Telecom that built 4G infrastructure and provided wholesale high-speed mobile traffic to domestic Internet service providers (see Chapter 5).

Co-ordinating the roll out and maintenance of different physical infrastructures can reduce the cost of installing communications infrastructure. Exploiting different types of physical infrastructure can also help cut costs. Some of the national and regional backbone projects have taken advantage of available electricity grids, railway lines and oil pipelines and of their right to install fibre-optic cables within the region. Power utility companies such as ESKOM (South Africa), NAMPower (Namibia) and Powertel (Zimbabwe) rolled out fibre-optic infrastructure. Zambia Telecom leased fibre-optic infrastructure from ZESCO, a state-owned power company, and Copperbelt Energy Corporation.

Developing regional communications infrastructure can also reduce the digital divide in Southern Africa. In 2012, the Southern African Development Community’s Regional Infrastructure Development Master Plan selected 18 ICT infrastructure projects to support, estimated to cost around USD 21.4 billion in the plan’s first phase, from 2012 to 2017 (SADC, 2019). By mid-2019, two projects were completed. Both of them focused on developing an integrated broadband infrastructure across the region; they included seven programmes for expanding the terrestrial fibre-optic network to connect landlocked countries to the undersea cable and four programmes for enhancing IXPs in the region. These projects should reduce Internet costs, given that most member states currently rely on telecommunications gateways in European countries to manage or direct digital traffic to the region and the rest of the African continent (Nhongo, 2018).

Proactive government efforts are critical to ensuring equitable access

Enabling regulatory frameworks are key to ensure universal access to and use of communications infrastructure, especially in remote and economically disadvantaged regions. They can facilitate infrastructure sharing, and open access wholesale models can help redirect resources towards under-served communities and reduce costs for end-users. In Zambia, the anticipation of a fourth operator entering the market was enough to spark a decrease in data prices by more than 70% between 2018 and 2019 (RIA, 2020b). Although the bulk of the investment required to expand Internet access can come from the private sector, active public interventions may be necessary to ensure coverage in remote areas that have limited commercial attractiveness (see Box 3.2).

Affordability is a serious concern for the equality of Internet use in South Africa. Only 36% of the country’s population can afford one gigabyte of data. According to a survey, 47% of South Africans list affordability of data as the primary constraint to Internet usage, with the cost of devices in second place at 36% (RIA, 2017). Unequal allocation of spectrum and cost-based facilities has affected the quality of Internet connections provided by smaller operators and prevented competition (Chetty et al., 2013). It also enabled the two largest operators, MTN and Vodacom, representing 74% of market shares in 2018, to maintain high prices despite aggressive pricing by competitors (CCSA, 2019).

In 2020, the leading operators reduced data prices in response to the South African Competition Commission’s threat of prosecution. In 2019, the Commission ruled for an immediate reduction of 30-50% on market leaders’ data prices and the provision of a “lifeline” package of daily free data for prepaid subscribers. As a result, MTN and Vodacom reduced their data tariffs from ZAR 149 to ZAR 99 (South African rand) per gigabyte effective 1 April 2020. Nonetheless, as these prices simply align with those of outside competitors, Cell C and Telkom, they may not necessarily increase Internet use by poorer households (RIA, 2020c).

Source: Authors’ compilation based on a literature review.

Some governments have launched national broadband plans with specific coverage targets. For example, South Africa aims to provide a minimum broadband speed of 5 megabits per second (Mbps) for its entire population and 100 Mbps for at least half of its population by the end of 2020. Botswana has set a target of 100 Mbps in urban areas and 50 Mbps rural areas by 2022.

The innovative use of TV white space can upgrade rural broadband networks at low cost. The TV white space reallocates unused broadcasting frequencies in the wireless spectrum for data transmission and Internet. In Malawi, tests of TV white space use for broadband were successful and were then replicated in Botswana, Mozambique, Namibia and South Africa. Two challenges remain for the widespread adoption of such technology. First, as of 2020, among Southern Africa’s countries only Eswatini, Lesotho, Malawi and Zambia have completed the transition from analogue to digital broadcasting to free up radio frequencies previously used by television channels. Others have progressed at a slower pace, largely due to funding and network constraints (ITU, 2020b). Second, using TV white space requires supporting regulation. In the case of Malawi, the necessary regulation was not ratified quickly enough to implement the technology nationally (Markowitz, 2019). South Africa, on the other hand, despite delays, published its technical regulations to establish a TV white space network and plans to deploy it commercially in early 2021 (Moyo, 2020).

Governments can better use their Universal Service and Access Funds (USAFs) to lead investment in remote areas. As of 2018, all Southern African countries, except Malawi, implemented a USAF – a special programme with funding schemes for universal Internet access and services (Thakur and Potter, 2018). Lesotho’s successful experience with administering its fund, established in 2009, provides a good example in the region. The programme fully spent its annual allocations while sustaining relatively low operating costs, below 20% of total revenues. Over the 2009-16 period, the programme benefited at least 110 000 people in 320 villages in rural areas, supporting the deployment of 46 base stations to remote areas and connecting 40 schools to the Internet. As of 2016, the programme has shifted its focus towards access to broadband by rolling out public Wi-Fi services (RIA, 2016).

Governments can use digital tools to expand the provision and quality of education

Countries must act now to assess the results of the most successful COVID-19 initiatives in digital education and must work together to scale them up to national and regional levels. Prior to the pandemic, the use of ICT in education was slowly growing in the region. In 2017, the government of Botswana launched e-Thuto, an interactive web-based platform bringing together teachers, students and parents and making educational material and administrative information easily accessible. Today, it serves close to 35 000 students in Southern Africa, from primary to high school level (Kuwonu, 2020). In Zambia, the Ministry of General Education is leveraging digital technologies to assess learning and track school performance through the Let’s Read project. This project aims to help 1.4 million children from more than 4 000 schools to read with comprehension and fluency in one of Zambia’s seven official local languages of instruction (World Bank, 2020d).

Enhancing the quality of foundational education is essential to prepare the workforce for the digital transformation. Currently, seven out of nine Southern African countries rank higher in digital skills development than the African average, according to the World Economic Forum’s Networked Readiness Index (WEF, 2016). Nonetheless, in most of the region’s countries, the education system is not configured to enable or to deal with issues emerging from digitalisation. Lack of foundational skills (i.e. literacy and numeracy) and of basic digital skills excludes the poorest from the benefits of digitalisation. In Lesotho, close to 60% of respondents identified digital illiteracy as the main reason for not using the Internet (RIA, 2016).

Updating education curricula according to industry needs is critical to reducing the prevailing skill mismatch in the region, especially in SACU countries. In Lesotho, for instance, no institution offers training in sewing machine repair, which is a skill in high demand in the apparel industry. Similarly, of the approximately 1 800 students enrolled at the National University of Lesotho, only about 40 major in ICT-related fields despite lower unemployment rates for graduates in those fields than for those in other fields (World Bank, 2018). Inputs from industry bodies, leaders and academia are necessary to drive the digital transformation of Southern Africa at the policy level. Formalised institutions facilitating these linkages, such as the Joburg Centre for Software Engineering in South Africa, can assist in this process (Markowitz, 2019). In addition, providing tailored career advice to students early in the schooling system could help reduce dropout, increase access to further education and improve labour market outcomes (OECD, 2017a).

Governments need to expand technical and vocational education and training (TVET) to ensure life-long learning

Expanding technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes could improve workers’ capabilities and facilitate the school-to-work transition (OECD, 2017b). The digital economy requires a range of skills, from the ability to use a mobile phone, the Internet and social media to the capacity to analyse advanced data, develop applications and manage networks. Skills development should not be limited to schools; it should also be available to the broader public through partnerships with TVET and community colleges. In South Africa, the government set the ambitious target of expanding the TVET college system to 2.5 million enrolments by 2030 as a way to reduce the 3.4 million young people not formally employed nor in education or training (Field, Musset and Álvarez-Galván, 2014). In Botswana, Malawi, Namibia and Zambia, UNESCO’s five-year Better Education for Africa’s Rise project assists local governments in improving their TVET systems by identifying relevant sectors (such as agro-processing and construction in Malawi) and potential partnerships to give youth a better chance of finding decent work (UNESCO, n.d.).

Public and private initiatives are helping disseminate entrepreneurial and digital skills. Initiatives such as those presented in Table 3.3 could contribute to addressing a wide variety of challenges that Southern African countries face, including high unemployment rates, informality and skills gaps, and to relieving pressure on the formal education system. In 2018, the government of Zimbabwe announced it would allocate USD 15 million for the construction of innovation hubs in six universities and the infrastructural overhaul of the higher and tertiary education sector (FurtherAfrica, 2019). In South Africa, the Inclusive Youth Employment Pay for Performance Platform has developed partnerships between several funders, investors, local government and service providers to train 600 young people in jobs in high-growth sectors (such as technology), and it expects to increase the partnerships to 5 400 jobs (Boggild-Jones and Gustafsson-Wright, 2019).

The region should develop a culture of lifelong learning to prepare for Africa’s digital transformation and adapt to future skills requirements. Southern African countries need to remain proactive in assessing future technological progress and anticipating skill needs. SACU countries, where a large share of the youth population have completed higher education, need to continuously improve workers’ capabilities through reskilling and upskilling programmes. Indeed, low-skill jobs that are intensive in routine tasks are the most susceptible to automation and offshoring. Thus, displaced workers will likely compete with other low-skilled workers for jobs with low and possibly decreasing wages (OECD, 2020). In addition, the recognition of skills acquired through previous work experience (formal or informal) could help individuals find employment opportunities or advance in their careers, especially as many Southern Africans have been denied access to formal education and training in the past (OECD, 2019b; OECD, 2017a).

Countries need to accelerate ongoing initiatives to harmonise regulations for an integrated digital economy in the region

Countries in Southern Africa have created a number of regional initiatives to realise an integrated digital economy and facilitate the digital transformation in the region.Table 3.4 lists prominent digital initiatives by countries in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Notably, Digital SADC 2027 provides the overarching framework for regional digitalisation, with a key focus on infrastructure, a coherent ICT regulatory framework and industrial development. Another important initiative is the plan by the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa to develop a Digital Free Trade Area (DFTA). The DFTA will be a digital platform enabling duty-free and quota-free trading and providing a regional market worth USD 17.2 billion (TrendsNAfrica, 2019).

A review of regional integration in SADC highlights 29 different strategies, plans, model laws, policy guidelines and frameworks related to ICT regulation at the SADC level since 2012 (SADC, 2019). These initiatives address new regulatory challenges at national and regional levels, such as taxation, consumer protection and digital security, inherent in the cross-border nature of the digital economy. They also provide a pragmatic and timely response to the rapidly evolving regulatory needs of the digital economy. For example, while the continent-wide 2014 Malabo Convention on Cyber Security and Data Protection has not yet entered into force, countries in Southern Africa have already agreed on a SADC model law for such emerging issues thanks to the European Union/International Telecommunication Union HIPSSA initiative, Support for Harmonisation of the ICT Policies in Sub-Saharan Africa (Greenleaf and Cottier, 2020).2

Countries need to accelerate the implementation of these initiatives, which has often encountered various difficulties. For example, the negotiation to abolish roaming charges that began in 2010 has not been fully completed due to resistance from private operators. Similarly, although the HIPSSA initiative has assisted countries in tailoring model laws to their national contexts, some remain unenforced at the national level. While most African countries have passed laws and promulgated regulations for managing the digital economy, these largely reflect domestic and not regional concerns. The changing priorities of member states and the slow implementation of integration initiatives sometimes lead to new policies overlapping with existing ones that are yet to be implemented (SADC, 2019; Markowitz, 2019).

Data governance to enable the seamless flow of information across borders is a critical regulatory area of focus. Southern Africa is characterised by a hub-and-spoke relationship where nine under-connected countries co-exist with one relatively hyper-connected country, South Africa. For example, South Africa has 21 data centres, while Angola has 3 and Zimbabwe 1. In 2020, three of the world’s biggest data companies − Microsoft, Amazon Web Services and Huawei − announced the establishment of cloud computing facilities in South Africa (Uwagbale, 2020). These investments aim not only to tap domestic clients in South Africa but also to serve the rest of the continent. The smooth flow of information between Southern African countries’ borders is vital to the competitiveness of the region as a whole, so consumers and producers in the digital economy can access the latest technologies.

The regional industrialisation strategy needs to embrace the digital transformation of strategic value chains

Embracing Africa’s digital transformation is critical to enhancing key value chains in Southern Africa. The Action Plan for SADC Industrialization Strategy and Roadmap focuses on building regional value chains in the agro-processing, mineral beneficiation, manufacturing and pharmaceutical sectors (the so-called “strategic growth paths”). Accelerating the digital transformation can help increase market participation and modernise these value chains. For example, the ongoing digital transformation at the global scale is likely to accelerate the servicification of manufacturing and the regionalisation of long and complex value chains such as the automotive industry (see Chapter 1). Similarly, blockchain applications can fundamentally improve the production, organisation and distribution of the agri-food industry in Africa. However, countries will need to tackle certain challenges to realise such potential (see Box 2.1 in Chapter 2).

Using blockchain requires digital capacity among actors in the value chains. An example is the first TRADO pilot for Malawi’s tea sector. TRADO is an initiative that aims to provide cheap financing for working capital to agricultural producers in exchange for supply chain data. The flow of data on products and supply chain party participation, enabled by blockchain, help improve pricing models of trade finance and reduce financing costs. The pilot, carried out with Unilever in 2018, showed a lower gain (a 0.68 percentage point increase) than expected (a 1-3 percentage increase). The lower gain resulted from buyers not having the capacity to carry out the digital transactions.

Countries should strengthen linkages between the digital innovation hubs and the actors in the strategic sectors. The region enjoys several hubs (see Table 3.5), such as the Southern Africa Innovation Support Programme (SAIS). The purpose of the SAIS initiative is to facilitate the growth of innovation ecosystems in Southern Africa. The programme is a partnership between the SADC Secretariat and the ministries responsible for science, technology and innovation in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania and Zambia. Connected Hubs, one of the programme’s components, aims to share best practices in innovation support and develop a networked community of innovation actors among the countries of SADC. Since its pilot in 2018, Connected Hubs has built bridges between 20 business support organisations across seven countries, supported over 500 early-stage entrepreneurs and strengthened 24 early-stage, impact-driven start-ups (SAIS, n.d.).

Co-operation among government authorities and the private sector is vital. Many digital applications and platforms operate across regulatory boundaries and conduct business in a number of sectors. The fintech sector, for instance, has proven to be a critical tool for upgrading the agri-business sector (see Chapter 2). Several government authorities share regulatory responsibility for this sector, such as central banks, ministries overseeing telecommunications and competition authorities. However, a recent review of policies for digitalisation in Lesotho, Malawi and South Africa reveals limited collaboration across government agencies (Markowitz, 2019). Strong leadership is critical to inspire a common vision towards the digital transformation across sectors, industries and government authorities and to foster dynamic collaboration among them.

References

Alper, C. and M. Miktus (2019), “Bridging the mobile digital divide in sub-Saharan Africa: Costing under demographic change and urbanization”, International Monetary Fund Working Papers, No. 19/249, www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/11/15/Bridging-the-Mobile-Digital-Divide-in-Sub-Saharan-Africa-Costing-under-Demographic-Change-48793.

Asif S. (2019), “Upcoming commercialization of 5G in South Africa”, MTN Consulting, www.mtnconsulting.biz/upcoming-commercialization-of-5g-in-south-africa/ (accessed 25 August 2020).

Aslam, Z., H. Bhorat and J. Page (2020), “Exploring new sources of large-scale job creation: The potential role of Industries without smokestacks”, Brookings Institutions, Washington, DC, www.brookings.edu/research/exploring-new-sources-of-large-scale-job-creation-the-potential-role-of-industries-without-smokestacks/.

AUC/OECD (2018), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2018: Growth, Jobs and Inequalities, OECD Publishing, Paris/AUC, Addis Ababa, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302501-en.

Baxter, D. (2020), “Africa must embrace digital infrastructure governance. PPPs can help”, World Bank, https://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/africa-must-embrace-digital-infrastructure-governance-ppps-can-help.

Boggild-Jones, I. and E. Gustafsson-Wright (2019), “First social impact bond in South Africa shows promise for addressing youth unemployment”, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, www.brookings.edu/blog/education-plus-development/2019/07/12/first-social-impact-bond-in-south-africa-shows-promise-for-addressing-youth-unemployment/.

BPESA (2019), GBS Sector Job Creation Report: Q4 2019, Business Process Enabling South Africa, Sandton, South Africa, www.bpesa.org.za/component/edocman/?task=document.viewDoc&id=213.

Browdie, B. (2020), “South Africans under lockdown have to deal with slow internet after another undersea cable break”, Quartz Africa, https://qz.com/africa/1828436/lockdown-south-africa-internet-slows-as-submarine-cable-snaps/ (accessed 25 August 2020).

CCSA (2019), Data Services Market Inquiry: Final Report, Competition Commission South Africa, www.compcom.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/DSMI-Non-Confidential-Report-002.pdf.

Chetty, M. et al. (2013), “Investigating Broadband Performance in South Africa: 2013”, Towards Evidence-based ICT Policy and Regulation, Vol. 2, www.researchictafrica.net/docs/RIA_policy_paper_measuring_broadband_performance_South_Africa.pdf.

Chigbu, B. and F. Nekhwevha (2020), “The extent of job automation in the automobile sector in South Africa”, Economic and Industrial Democracy, SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X20940779.

Crunchbase (2020), Crunchbase Pro (database), www.crunchbase.com (accessed 28 June 2020).

Demirgüç-Kunt, A. et al. (2018), The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution, World Bank, Washington, DC, http://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/global-findex (accessed 1 February 2020).

Fairwork Foundation (2020), Gig Workers, Platforms and Government during Covid-19 in South Africa,https://fair.work/wp-content/uploads/sites/97/2020/05/Covid19-SA-Report-Final.pdf.

Fanta, A. et al. (2016), The role of mobile money in financial inclusion in the SADC region: Evidence using Finscope surveys, Policy research paper No. 3/2016, FinMark Trust, Midrand, South Africa, www.finmark.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/mobile-money-and-financial-inclusion-in-sadc.pdf.

FAO (2018), The International Symposium on Agricultural Innovation for Family Farmers: 20 Success Stories of Agricultural Innovation from the Innovation Fair, Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, www.fao.org/3/CA2588EN/ca2588en.pdf.

Field, S., P. Musset and J. Álvarez-Galván (2014), A Skills beyond School Review of South Africa, OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264223776-en.

FurtherAfrica (2019), Report: Digital Opportunities Southern Africa’s Offering in 2019,https://furtherafrica.com/2019/06/02/report-digital-opportunities-southern-africas-offering-in-2019/ (accessed 25 August 2020).

Gallup (2019), Gallup World Poll (database), www.gallup.com/analytics/232838/world-poll.aspx (accessed 1 February 2020).

Genesis Analytics (2019a), Evaluation of Phase 1 Implementation of Interventions in the National Health Insurance (NHI) Pilot Districts in South Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa, www.hst.org.za/publications/NonHST%20Publications/nhi_evaluation_report_final_14%2007%202019.pdf.

Genesis Analytics (2019b), South Africa in the Digital Age, Johannesburg, South Africa, www.genesis-analytics.com/sada.

Greenleaf, G. and B. Cottier (2020), Comparing African Data Privacy Laws: International, African and Regional Commitments, University of New South Wales Law Research Series, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3582478.

GSMA (2020a), GSMA Intelligence (database), Global System for Mobile Communications Association, www.gsmaintelligence.com (accessed 28 June 2020).

GSMA (2020b), “618 active tech hubs: The backbone of Africa’s tech ecosystem”, www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/blog/618-active-tech-hubs-the-backbone-of-africas-tech-ecosystem/ (accessed 28 June 2020).

GSMA (2019), 5G in Sub-Saharan Africa: Laying the Foundations,https://data.gsmaintelligence.com/api-web/v2/research-file-download?id=45121572&file=2796-160719-5G-Africa.pdf.

ICASA (2020), State of the ICT Sector Report: 2020, Independent Communications Authority of South Africa, Centurion, South Africa,www.icasa.org.za/legislation-and-regulations/state-of-the-ict-sector-in-south-africa-2020-report.

IFC (2019), Creating Markets in Angola: Opportunities for Development through the Private Sector, International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/606291556800753914/pdf/Creating-Markets-in-Angola-Opportunities-for-Development-Through-the-Private-Sector.pdf.

ILO (2020), ILOSTAT (database), International Labour Organization, Geneva, https://ilostat.ilo.org/.

ITU (2020a), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database, www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx (accessed 1 February 2020).

ITU (2020b), “Status of the transition to Digital Terrestrial Television”, International Telecommunication Union, Geneva, Switzerland, www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Spectrum-Broadcasting/DSO/Pages/default.aspx (accessed 25 August 2020).

Klonner, S. and P. Nolen (2010), “Cell phones and rural labor markets: Evidence from South Africa”, Proceedings of the German Development Economics Conference, Hannover 2010, No. 56, www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/39968.

Kuwonu, F. (2020), “Botswana e-learning initiative wins prestigious UN Public Service Award”, Africa Renewal,www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/june-2020/botswana-e-learning-initiative-wins-prestigious-un-public-service-award (accessed 25 August 2020).

Lancaster, H. (2020), South Africa: Telecoms, Mobile and Broadband: Statistics and Analyses, 17th edition, Paul Budde Communications Pvt. Ltd., Australia, www.budde.com.au/Research/South-Africa-Telecoms-Mobile-and-Broadband-Statistics-and-Analyses.

Markowitz, C. (2019), Harnessing the 4IR in SADC: Roles for Policymakers, Occasional Paper 303, South African Institute of International Affairs, South Africa, https://media.africaportal.org/documents/Occasional-Paper-303-markowitz.pdf.

McKinsey & Company (2019), The Future of Work in South Africa: Digitisation, Productivity and Job Creation, Sandton, South Africa, www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/middle%20east%20and%20africa/the%20future%20of%20work%20in%20south%20africa%20digitisation%20productivity%20and%20job%20creation/the-future-of-work-in-south-africa.pdf.

Moyo, A. (2020), “ICASA, Black IT Forum trade blows over TV white spaces”, ITWeb, www.itweb.co.za/content/Kjlyr7w1mB5qk6am (accessed 25 August 2020).

Nhongo, K. (2018), “SADC ministers to review regional programme on ICT development”, Southern Africa Research and Documentation Centre, Harare, Zimbabwe, www.sardc.net/en/southern-african-news-features/sadc-ministers-to-review-regional-programme-on-ict-development/.

OECD (2020), “Technology and the future of work in emerging economies: What is different”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 236, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/55354f8f-en.

OECD (2019a), “The road to 5G networks: Experience to date and future developments”, OECD Digital Economy Papers, No. 284, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2f880843-en.

OECD (2019b), Community Education and Training in South Africa, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264312302-en.

OECD (2017a), Getting Skills Right: South Africa, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278745-en.

OECD (2017b), Getting Skills Right: Good Practice in Adapting to Changing Skill Needs: A Perspective on France, Italy, Spain, South Africa and the United Kingdom, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264277892-en.

RIA (2020a), Mobile Pricing (database), Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, https://researchictafrica.net/ramp_indices_portal/ (accessed 28 June 2020).

RIA (2020b), “Uzi’s failed attempt to enter Zambian market leads to more than 70% fall in data prices”, Policy Brief 2, Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Zambia_SNT_RAMP_policy_brief_2-2019.pdf.

RIA (2020c), “Despite reduction in mobile data tariffs, data still expensive in South Africa”, Policy Brief 2, Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Zambia_SNT_RAMP_policy_brief_2-2019.pdf.

RIA (2018a), After Access 2018: A Demand-side View of Mobile Internet from 10 African Countries, Policy Paper Series No. 5 After Access: Paper No. 7, Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/2019_After-Access_Africa-Comparative-report.pdf.

RIA (2018b), The State of ICT in Mozambique 2018, RIA Policy Paper No. 6, Vol. 5, After Access, Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, https://researchictafrica.net/2019_after-access_the-state-of-ict-in-mozambique/.

RIA (2017), “Low Internet penetration despite 90% 3G Coverage in Lesotho”, Policy Brief 2, Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2017_Policy_Brief_5_Lesotho-.pdf.

RIA (2016), The State of ICT in Lesotho, Research ICT Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/2017_The-State-of-ICT-in-Lesotho_RIA_LCA.pdf.

SADC (2019), Status of Integration in the Southern African Development Community, Southern African Development Community Secretariat, Gaborone, Botswana, www.sadc.int/files/9915/9154/2991/Status_of_Integration_in_the_SADC_Region_Report.pdf.

SAIS (n.d.), “SAIS programme and networking”, South African Innovation Support, www.saisprogramme.org/networking (accessed 25 August 2020).

SMART (2011), “Western Cape Education Department, South Africa: Khanya Technology in Education Project”, http://downloads01.smarttech.com/media/sitecore/en/pdf/research_library/implementation_profiles/110104_southafrican_moe_profile.pdf (accessed 25 August 2020).

South African Revenue Service (2018), SARS Annual Report 2018/19, https://static.pmg.org.za/SARS_Annual_Report_201819_WEB.pdf.

Telecompaper (2018), “South Korean operators to invest KRW 4 trillion in 5G networks in H1”, www.telecompaper.com/news/south-korean-operators-to-invest-krw-4-trillion-in-5g-networks-in-h1--1329465 (accessed 25 August 2020).

Thakur, D. and L. Potter (2018), Universal Service and Access Funds: An Untapped Resource to Close the Gender Digital Divide, World Wide Web foundation, Washington, DC, https://webfoundation.org/docs/2018/03/Using-USAFs-to-Close-the-Gender-Digital-Divide-in-Africa.pdf.

Trendsnafrica (2019), “COMESA to establish Digital Free Trade Area (DFTA)”, http://trendsnafrica.com/2019/06/13/comesa-to-establish-digital-free-trade-area-dfta/ (accessed 25 August 2020).

UNCTAD (2020), UNCTADSTAT (database), United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/wds/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx (accessed 1 May 2020).

UNESCO (2020), “National learning platforms and tools”, https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/nationalresponses.

UNESCO (n.d.), “BEAR – transforming skills in sub-Saharan Africa”, https://en.unesco.org/news/bear-%E2%80%93-transforming-skills-sub-saharan-africa (accessed 25 August 2020).

Uwagbale, E. (2020), “Why Amazon is expanding web services in Africa but still has no e-commerce here”, Quartz Africa, https://qz.com/africa/1849378/amazon-expanding-web-services-in-africa-but-no-e-commerce/.

WEF (2016), The Global Information Technology Report 2016: Innovating in the Digital Economy, World Economic Forum, Geneva, www3.weforum.org/docs/GITR2016/WEF_GITR_Full_Report.pdf.

Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (2018), Wittgenstein Centre Data Explorer Version 2.0 (Beta) (database), www.wittgensteincentre.org/dataexplorer (accessed 1 March 2020).

World Bank (2020a), Enterprise Surveys (database), www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data (accessed 28 June 2020).

World Bank (2020b), World Development Report 2020: Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains, World Bank, Washington, DC.

World Bank (2020c), PovCalNet (database), http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/home.aspx (accessed 28 June 2020).

World Bank (2020d), Accelerating Digital Transformation in Zambia: Digital Economy Diagnostic Report, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33806.

World Bank (2019), Digital Economy for Mozambique Diagnostic Report, World Bank, Washington, DC, http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/833211594395622030/Mozambique-DECA.pdf.

World Bank (2018), Unlocking the Potential of Lesotho’s Private Sector: A Focus on Apparel, Horticulture, and ICT, World Bank Group, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/832751537465818570/Unlocking-the-potential-of-Lesotho-s-private-sector-a-focus-on-apparel-horticulture-and-ICT.

World Bank (2017), “Digital Malawi Program Phase I: Malawi Digital Foundations Project”, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P160533#abstract.

Zizzamia, R. et al. (2020), “The labor market and poverty impacts of COVID-19 in South Africa”, CSAE Working Paper Series 2020-14, Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford, https://ideas.repec.org/p/csa/wpaper/2020-14.html.

Notes

← 1. In Southern Africa, Angola and Mozambique also have active IXPs.

← 2. Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi and South Africa have enacted data privacy laws as far back as 2011. Zimbabwe enacted a data privacy law for the public sector in 2002. Eswatini and Zambia have also introduced or prepared data protection bills.