Chapter 5. The regulation issuing process in Peru

In this chapter, the process to issue regulations followed by five ministries of Peru is thoroughly analysed and compared with the practices of regulatory impact assessment, according to the OECD countries’ standards.

The main objective of this review is to support the Peruvian government in the adoption of RIA as a tool to ensure the quality of the regulation that it issues, either for new proposals or to modify the existing ones. Before identifying and assessing the current process to issue regulations in Peru, it is necessary to identify the most common elements used by the OECD countries in the RIA process and, thus, be able to make a comparison with the process followed in Peru.

Good RIA practices in OECD countries

Table 5.1 shows a list of the most common elements found in the RIA systems of OECD countries. Taken together, they represent the good practices for the ex ante analysis of regulations. Their importance and relevance are briefly explained below and more detailed in Chapter 7.

Definition of the problem

Defining the existing problem is the first step of the RIA and, consequently, of the process to issue regulations. Insofar as the problem is properly identified – its dimensions and origin – it will be possible to design instruments that reduce or eliminate the risks. A poorly identified problem is the prelude to misguided policies and substandard results, at best. Undoubtedly, the identification of the problem is the most important step of any regulatory impact assessment.

Public policy objectives

Once the problem is identified – the possible effects and consequences – and that government intervention is justified, the RIA should set out specific goals aimed to solve the causes of the problem in question.

A very common mistake is confusing “means” and “ends”. The regulatory objective is the “final result” that the government wants to achieve. This should not be confused with the “means” to achieve it because, otherwise, it excludes all the alternatives that may exist. For instance, a public policy objective may be to reduce the number of deaths due to traffic accidents, reducing the speed limit is a means to achieve the goal, but it is not the goal itself. Other means may be to require particular safety measures or to improve road conditions. This example shows that there are several ways and options to achieve the goal.

Alternatives to the regulation

In many cases, the initial analysis done through the RIA may indicate that regulating is not the best option. Some other type of tool can allow to achieve the goals we pursue in a more efficient and effective way. In those cases, the RIA can help, for it gives more insight into the possible impacts of alternative approaches to regulation to achieve public policy objectives. On the other hand, the analysis may reveal that the government intervention is not necessary.

RIA can conclude that the status quo may be the more efficient approach to solve the problem, this can occur in the following cases:

-

When the size of the problem is so small that the costs of government action are not justified, and

-

When the analysis proves that a rule, or any other action, is not feasible to address effectively the problem at a reasonable cost, thus not getting a positive benefit.

Impact evaluation: cost-benefit analysis

The information about costs and benefits can be of two types: quantitative and qualitative (see Box 7.7 and Box 7.8 for a brief explanation of the methodologies). Quantitative information is expressed in numerical terms, and sometimes in monetary ones. It is the most useful for decision makers, as it allows them to weigh the magnitude of the benefits and costs – analysed and expressed in monetary terms – , when comparing the impact of the different alternatives.

This means that quantitative information should be obtained –insofar as possible –about the size of the problem, the costs of regulatory action, and the expected benefits. In many cases, however, it is impossible to determine the monetary terms for the quantitative analysis. Then, qualitative information can also be part of the analysis. It is important to present the information as clearly and objectively as possible; for, those who read the analysis could interpret in different ways the qualitative information of a potential problem.

The cost-benefit analysis can be considered both as a decision-making guide and as a typical methodology of RIA. The analysis should be the basis for all RIAs of high-impact regulations. This would help ensure the regulation is only issued when the benefits are greater than the costs it imposes.

As a methodology, the cost-benefit analysis represents the best practice to conduct a RIA. In fact, the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance established that member countries and associates of the OECD should “adopt practices of ex ante impact assessment that are proportional to the regulation and include a cost-benefit analysis that takes into account the impact of the regulation the wellbeing” (OECD, 2012[1]). The cost-benefit analysis provides a sound basis to compare alternatives and guide decisions among several options, for the quantification of benefits and costs in monetary terms and the comparison over a certain period backs it up.

Compliance with regulation

An important element of evaluating impacts is to make a realistic analysis of the compliance rate that is expected to be achieved with the draft proposal. The regulation will only have an impact if people comply with it.

In general, if compliance rates tend to be low, it is essential to be able to detect or reduce noncompliance through implementation actions. If not possible, then a failure in regulation may occur. It means reconsidering the regulatory proposal and check if there is an alternative mechanism that could be more effective.

Monitoring and evaluation

The monitoring and evaluation of the regulatory proposal will make it possible to clearly identify if the public policy objectives are being achieved, as well as to determine if the proposed regulation is needed or how can it be more effective and efficient to reach the stated objectives.

From the very moment the regulation is designed, the mechanisms to be used should also be devised; which, therefore, must be implemented to monitor if compliance with regulation leads to accomplish the objectives set out in the beginning. Likewise, the mechanisms that will be created to make an evaluation of the performance of regulations – also known as ex post evaluation – , should be foreseen. The ex post evaluation will allow to determine if the regulation contributed to solve the identified problem and, therefore, to accomplish the public policy objective.

Public consultation

One of the most effective ways to obtain information that supports the RIA is to consult potentially affected groups. Furthermore, consultation helps to legitimise regulation because people is able to question and participate in the regulatory process before the regulation is enforced. In this way, voluntary compliance with regulation can increase.

Although consultation is an effective way to obtain information and data to prepare the RIA, it is also necessary to provide enough information to support the consultation process itself. People will participate more fully in the consultation if they know the regulatory proposal and the problem intended to be solved. Written materials explaining all this must be made available to the groups in advance, so they can read and analyse them. Specific questions can be devised to help getting information about concrete subjects. The consultation process should be open enough for groups to express their doubts. Thanks to this, the process will be better accepted by all and, in some cases, it may alert about possible problems that have not been widely considered.

The timing for consultation is also relevant. First, carrying out consultation should be as soon as possible and at various times of the regulatory process so that the results are efficiently used in the RIA or, potentially, lead to changes in the regulatory proposal. Second, it must be ensured that groups have enough time to consult and, in fact, to participate.

In the long term, people will participate in the consultation if they feel it is worth doing so. That means that their opinions should be taken into account during the regulatory process. Replying to their questions or doubts is a good way to maintain the spirit of the participants. The responses to the consultation must be posted on the Internet, along with the details of the government’s reaction to the opinions.

Process to issue regulations in Peru

In order to identify the legal provisions, the institutional rules and the current practices on the ex ante evaluation of regulatory proposals in Peru, a mapping of what could be considered the regulatory governance cycle in the country was carried out for a group of ministries. This mapping is exclusively for the 2014-16 period, it does not includes the ACR evaluation.1 However, the changes to the mapping of the regulatory governance cycle in the five selected ministries brought about by the introduction of the ACR are considered at the end of this chapter.

As mentioned above, the regulatory governance cycle is a process by which the government identifies a public policy problem and decides to address it by enforcing an instrument in particular, which should be assessed before being issued. These are the five ministries selected for analysing their process to issue regulations:2

-

Ministry of Economy and Finance

-

Ministry of Production

-

Ministry of Environment

-

Ministry of Transport and Communications

-

Ministry of Housing, Construction and Sanitation

Each of the processes shown and analysed below was created from in-depth interviews hold with representatives of the ministries, to prepare a pilot project and the review of the regulatory framework of Peru.

The identified process in each ministry is described, and its consistency with good RIA practices of the OECD countries is evaluated.

Process to issue regulations in the Ministry of Economy and Finance

Figure 5.1 shows the process to issue regulations identified in the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF).

1. Definition of the problem

The first in the MEF is the definition of the problem. There is not a systematised process in the MEF to identify the problem, such as a checklist of questions or criteria. Nevertheless, enough evidence was found in the cases reviewed (see Chapter 2) to conclude that the definition of the problem is consistent with the RIA practices.

In this stage, there are efforts in the MEF to define public policy objectives. In general, the objectives to be achieved are described in the explanatory statement of the regulations. There are still, however, important areas of opportunity to provide a clear definition of the public policy objective, especially in the case of high-impact regulations, where the objectives to be reached should be defined in terms of parameters.

2. Development of the proposal

After the identification of the problem, the MEF draws up the regulatory proposal in the offices with authority to perform this task.

3. Socialisation of the proposal

Once the proposal is prepared, it is subject to a socialisation stage, where other directorates of the MEF or agencies with shared tasks or relation to the subject matter examined make their comments on the proposal. The socialisation of the proposal is an ad hoc process and the comments received are not available to the public.

4. Impact analysis

After socialising the proposal with the areas and public entities interested in the subject, the MEF carries out an impact analysis. Before January 2017, this analysis was occasionally and unsystematically and, unless it was a multisector regulation and, consequently, reviewed by the CCV, there was no monitoring of its compliance. Even if the regulatory proposal was submitted to the CCV, there was not always an impact analysis. As of January 2017, the MEF, the MINJUSDH and the PCM created a committee —as a pilot program— to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals. This committee advice the bodies issuing regulation on how to perform the analysis, on a case-by-case basis. However, there are no formal guidelines for its operation yet (see Chapter 6).

The impact analysis can be quantitative or qualitative, as applicable. On very few occasions, however, the MEF does a quantitative impact analysis. Although it carries out a qualitative one more frequently, it is still not performed in a systematic way.

This area of opportunity is even more important for the MEF, since it is in the finance division where the availability of data is wider and, consequently, conditions are more favorable to perform a cost-benefit analysis.

5. Legal advice

The legal advice of regulatory proposals is a step prior to the pre-publication, and it is generally a responsibility of the legal office of the MEF. This advice has a twofold purpose: first, that the draft of the regulatory proposal meet the form requirements and, second, that there be no controversy with another legal instrument.

6. Pre-publication of the proposal

Once the legal office prepares and reviews the proposal, the MEF pre-publishes it in the Official Gazette El Peruano, and on its transparency website. This publication is mandatory due the Supreme Decree DS-001-2009-JUS on its Article 14, which states the obligation of publishing general regulatory proposals in the Official Gazette El Peruano, on the websites or in any other medium for a minimum period of thirty days.

The main opportunity area of the pre-publication of regulatory proposals lies in their legal basis, since it does not mentions an obligation regarding the handling of public comments. That is, the ministries are not obliged to publish the comments or to reply to them, and although the MEF does so occasionally, it is not a common practice.

7. Review by the General Secretariat

With the final version of the proposal, the General Secretariat of the MEF conducts a final review to analyse the consistency of the regulation with the general administration and with the ministry itself.

8. Submission and approval by the CCV

The CCV must analyse the regulation involving multiple sectors for its approval. The nature and tasks of the CCV are explained in Box 5.1.

The Vice-Ministerial Coordinating Council (CCV) is the body that analyses and approves multisectoral regulation.1 It is comprised by the deputy ministers of the central government and the Secretary General of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, who chairs the meetings. The CCV has three main tasks.2

-

1. Express a well-founded opinion about the Law Projects, Legislative Decree Projects, Urgency Decree Projects, Supreme Decree Projects and Supreme Resolution Projects that either require the approving vote of the Council of Ministers or are related to multiple sectors.

-

2. Facilitate the generation of input and recommendations in response to reports on multisectoral themes that are of high national interest or that affect the general policy of the government,

-

3. Approve the CCV rules of procedure.

According to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, the CCV holds a standardised procedure with the help of ICT tools for the process of reviewing regulation. The process starts on Monday when the Coordination Secretariat of the PCM organises a tentative agenda for the week’s meeting. After receiving and integrating the proposals from the ministries, the Premier decides what is to be included in the agenda and it sends an invitation for the weekly voting meeting to be held on Thursday. Before the meeting, the 35 deputy ministers have until Wednesday to upload in the digital platform the observations, comments, and corresponding documentation. The possible range of status of the draft regulatory instruments after the assessment of the CCV is the following:

-

Viable without observations;

-

Viable with observations;

-

Not viable, and

-

Viable with comments.

The matters considered as comments are those regarding grammatical and formatting aspects such as commas, numerals, etc. The observations, on the other hand, contain a discussion about the substance of the regulatory projects. When comments arise, the meeting discusses them on Thursday. In contrast, the observations have to be thoroughly discussed and they often cause the regulation to stall in the CCV. The voting is generally delivered physically during the meetings, although the deputy Ministries who are not able to attend the meetings can use the CCV’s digital platform.

← 1. 1.3. About the Ministerial Resolution Nº 251-2013-PCM: General Rules of the Vice-Ministerial Coordination Council.

← 2. Art. 4. Ibid.

Source: (OECD, 2016[2]), Regulatory Policy in Peru: Assembling the Framework for Regulatory Quality, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264260054-en.

9. Publication of the regulation

Once the CCV approval is available, if it refers to multisectoral regulation or, in the rest of the cases, when the MEF sends directly the regulation, the proposal is published in the Official Gazette El Peruano. In the case of Ministerial Resolutions, for law-level regulation, they would have to follow their process for sending it to the Congress.

Lack of RIA practices

In the process to prepare the regulation, there was no evidence that the MEF performs an analysis of the necessary measures to ensure compliance with regulations, nor of the measures taken for monitoring and evaluating the regulation.

Likewise, before implementing the pilot committee for reviewing the impact analysis of regulatory proposals introduced in January 2017, no evidence was found that in the preparation process the MEF perform an analysis of alternatives to the regulation.

Process to issue regulations in the Ministry of Production

Figure 5.2 shows the identified process to issue regulations in the Ministry of Production (PRODUCE).

1. Definition of the problem

The first step identified in PRODUCE is the definition of the problem. PRODUCE employs thematic working groups with the relevant actors to discuss recurrently the problems that affect the sector. This is consistent with the “early consultation” practice, that can help to define the nature and scale of the problems (see chapters 7 and 8). Depending on the subject in question, Produce invited to participate representatives of the industry, other ministries and, even, occasionally, officials from the municipalities.

In this stage, there are efforts in PRODUCE to define public policy objectives. In general, the objectives to be achieved are described in the explanatory statement of the regulations. There are still, however, important areas of opportunity to provide a clear definition of the public policy objective.

2. Development of the proposal

After the identification of the problem, PRODUCE draws up the regulatory proposal in the relevant offices with authority to issue regulations.

3. Socialisation of the proposal

Once the proposal is prepared, PRODUCE socialises it with other areas of the same ministry or agencies with shared tasks or relation to the subject matter examined, so that they make comments on the proposal. The socialisation of the proposal is an ad hoc process and the comments received are not available to the public.

4. Impact analysis

After socialising the proposal with the areas and public entities interested in the subject, PRODUCE carries out an impact analysis. Before January 2017, PRODUCE did this analysis occasionally and unsystematically, there was no monitoring of its compliance unless it was a multisectoral regulation and the CCV had to review it; moreover, there was not always an impact analysis. It is also performed a proportionality analysis, but it depends on the size of the alterations to the industry.

As of January 2017, the MEF, the MINJUSDH and the PCM created a committee – as a pilot programme – to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposal. This committee advises the regulation-issuing bodies on how to perform it, on a case-by-case basis, although there are no formal guidelines.

On very few occasions, PRODUCE does a quantitative impact analysis; although it carries out a qualitative one, it is not performed in a systematic way. There is a Directorate of Economic Studies subordinated to the General Secretariat that could do the impact analyses of regulations in a systematic way.

5. Legal advice

The legal advice of the regulatory proposals is a step prior to the pre-publication, and it is generally a responsibility of the legal office of PRODUCE. This advice has a twofold purpose: first, that the draft of the regulatory proposal meets the form requirements and, second, that there is no controversy with another legal instrument.

6. Pre-publication of the proposal

Once the proposal has been prepared and reviewed by the legal office, it sends it to the General Secretariat for its pre-publication in the Official Gazette El Peruano and on its transparency website, based on the Supreme Decree DS-001-2009-JUS. The article 14 of it states the obligation of publishing general regulatory proposals in the Official Gazette El Peruano, on the websites or in any other medium, for a minimum period of thirty days.

The main area of opportunity of the pre-publication of regulatory proposals lies in their legal basis, since the Supreme Decree does not mention an obligation on the handling of public comments. As a result, the ministries are not obliged to publish the comments or to reply to them; although PRODUCE does so occasionally, it is not a common practice.

7. Review by the General Secretariat

With the final version of the proposal, the General Secretariat of PRODUCE conducts a final review to analyse the consistency of the regulation with the general administration and with the ministry itself.

8. Submission and approval by the CCV

If the regulation involves multiple sectors, the relevant vice-ministerial office has to send it to the CCV for analysis and its approval.

9. Publication of the regulation

Once the CCV approves it, if it is a multisectoral regulation or PRODUCE sends the regulation directly, the proposal is published in El Peruano. In the case of Ministerial Resolutions, for law-level regulation, it has to follow the process for sending it to the Congress..

Lack of RIA practices

In the process to prepare the regulation, there is no evidence that PRODUCE performs an analysis of the necessary measures to ensure compliance with regulations, nor of the measures taken for monitoring and evaluating the regulation. Regarding an oversight function, the responsibility is split: on one side, the OEFA supervises the environmental tasks, while in others it depends on the sector, for instance, fisheries; consequently, there is not a division in charge of the sanctioning procedures and oversight on a crosscutting basis.

Likewise, before implementing the pilot committee to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals introduced in January 2017, there is no evidence that PRODUCE performs an analysis of alternatives to the regulation in the process to prepare regulations.

Process to issue regulations in the Ministry of Environment

Figure 5.3 shows the process to issue regulations identified in the Ministry of Environment (MINAM).

1. Definition of the problem

The first step identified in the MINAM is the definition of the problem. The MINAM usually holds informal meetings with representatives from the regulated sectors to collect information and define better the problem. They do this through forums, workshops, and working groups. They also employ international environmental programs to define the existence of a problem in which they must step in. This activity is consistent with the “early consultation” practice, that can help to define the nature and scale of the problems (see Chapters 7 and 8).

In this stage, there are efforts in the MINAM to define public policy objectives. In general, the objectives to be achieved are described in the explanatory statement of the regulations. Nevertheless, there are still important areas of opportunity to provide a clear definition of the public policy objective, for political or media conditions in some cases determine the definition of the problem, rather than by facts based on evidence.

2. Development of the proposal

After the identification of the problem, the MINAM draws up the regulatory proposal in the competent division according to the subject matter.

3. Socialisation of the proposal

Once MINAM prepares the proposal, the Ministry socialises it with other areas of the same ministry or agencies with shared tasks or relation to the subject matter examined, so that they make comments on the proposal. As this is an ad hoc process, the comments received are not available to the public.

4. Impact analysis

After socialising the proposal with the areas and public entities interested in the subject, the MINAM carries out an impact analysis. As the MINAM lacks information, in few occasions this analysis is done in a quantitative way. It usually does it in a qualitative way, even sometimes it performs a comparison with international benchmarks. However, the impact analysis is not systematical.

As of January 2017, the MEF, the MINJUSDH and the PCM created a committee – as a pilot programme – to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals. This committee advises the regulation-issuing bodies on how to perform it, on a case-by-case basis, although there are no formal guidelines.

One of the main limitations the MINAM reports is the lack of data to perform the assessments and the lack of capacity building workshops for staff. Chapter 7 recommends strategies for data collection and training.

Legal advice

Prior to the pre-publication, the proposal is sent to the legal advice unit of MINAM’s legal office. This advice has a twofold purpose: first, that the draft meets the form requirements or legislative technique ones and, second, that there be no controversy with another instrument of the legal framework in force.

6. Pre-publication of the proposal

Once the proposal has been prepared and reviewed by the legal office, the MINAM continues with the pre-publication in the Official Gazette El Peruano and on its transparency website, based on the Supreme Decree DS-001-2009-JUS. The article 14 of it states the obligation of publishing general regulatory proposals in El Peruano, on the websites or in any other medium, for a minimum period of thirty days. Furthermore, the MINAM has the obligation to conduct an early consultation according to the regulatory framework of the sector.

The main area of opportunity of the pre-publication of regulatory proposals lies in their legal basis, since it does not mentions any obligation regarding the handling of public comments. That is, the ministries are not obliged to publish the comments or to reply to them.

Nevertheless, a practice that is considered appropriate —but only carried out by the MINAM— consists in preparing a matrix of comments for its publication and analysis after the pre-publication. The MINAM collects public comments and includes them in a matrix of comments. This matrix includes the responses from the MINAM to public comments.

Afterwards, the MINAM holds meetings with the groups that made comments in order to clarify and clear up doubts. The MINAM anew draws up the regulatory proposal with the information obtained from the meetings. As MINAM’s consultation practice is more advanced and consistent with RIA practices in the OECD countries, this should be replicated in all ministries.

7. Review by the General Secretariat

With the final version of the proposal, the responsible area sends it to the General Secretariat of MINAM to check the legal compliance. That is, to analyse the consistency of regulation with the general public administration and with the ministry itself.

8. Submission and approval by the CCV

If the regulation involves multiple sectors, the Ministry has to send it to the CCV for analysis and its approval.

9. Publication of the regulation

Once the CCV approves it, if it is a multisectoral regulation or when the MINAM send the regulation directly, the proposal is published in the Official Gazette El Peruano. In the case of Ministerial Resolutions, for law-level regulation, it has to follow the process for sending it to the Congress.

Lack of RIA practices

In the process to prepare the regulation, the MINAM does not performs an analysis of the measures necessary to ensure compliance with regulations, nor of the measures taken for monitoring and evaluating the regulation.

Likewise, before implementing the pilot committee to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals introduced in January 2017, in the process to prepare regulations the MINAM does not performs an analysis of alternatives to the regulation.

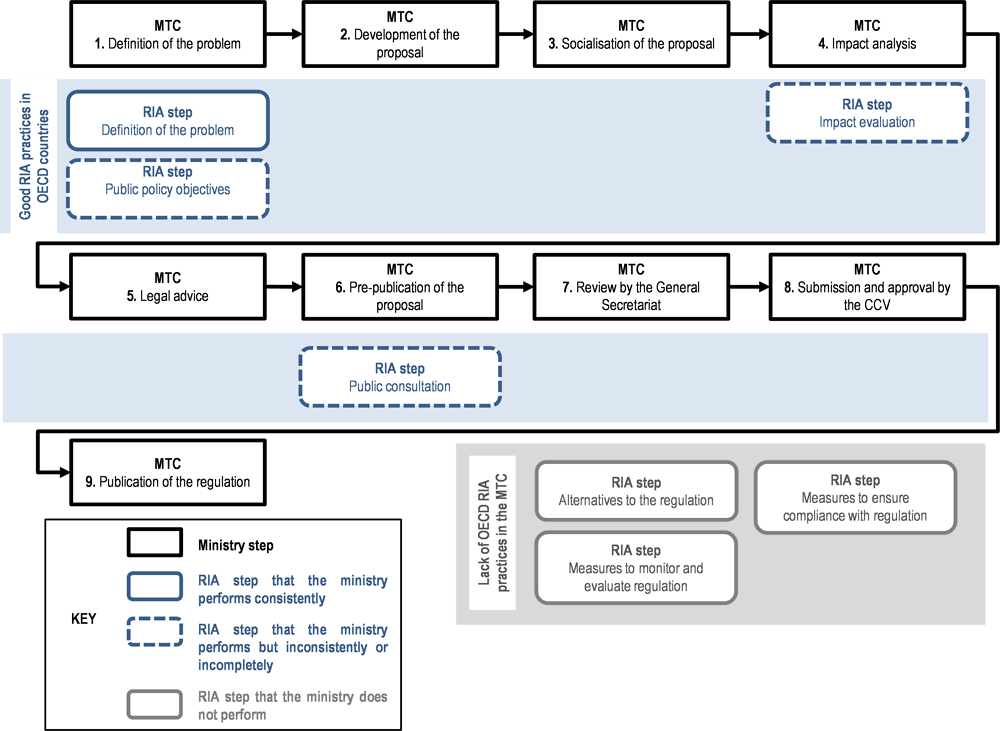

Process to issue regulations in the Ministry of Transport and Communications

Figure 5.4 shows the process to issue regulations identified in the Ministry of Transport and Communications (MTC)

1. Definition of the problem

The first step identified in the MTC is the definition of the problem. The experience of the MTC –in telecommunications –includes the co-ordination with the Supervisory Agency for Private Investment in Telecommunications (OSIPTEL) for the understanding of the regulatory problems. As to the transportation sector, based on the scale of the problem or the impact it might have on a certain industry, it could previously decide to meet for delineating and defining whether or not there is a problem that should be addressed.

In this stage, there are efforts in the MTC to define public policy objectives. In general, the objectives to be achieved are described in the explanatory statement of the regulations. There are still, however, important areas of opportunity to provide a clear definition of the public policy objective.

2. Development of the proposal

After the identification of the problem, it draws up the draft proposal according to the sector: telecommunications or transportation.

3. Socialisation of the proposal

Once the MTC prepares the project, it is subject to a socialisation stage, where other directorates of the Ministry or agencies as well as the regulated companies, make their comments on the proposal. As this is a non-standardised process, the comments received are not available to the public.

Impact analysis

After socialising the proposal with the areas and public entities interested in the subject, the MTC carries out an impact analysis. Before January 2017, MTC did this analysis occasionally and unsystematically, there was no monitoring of its compliance unless it was a multisectoral regulation and the CCV had to review it. Even when the Ministry submits the proposal to the CCV, there is not always an impact analysis.

As of January 2017, the MEF, the MINJUSDH and the PCM created a committee – as a pilot programme – to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals. It advises the regulation-issuing bodies on how to perform it, on a case-by-case basis, although there are no formal guidelines.

On very few occasions, the MTC does a quantitative impact analysis. Although it carries out a qualitative one, it is not systematically.

One of the main limitations the MTC reports is the lack of data to perform the evaluations and the time needed to do so, and not so much the training of officials, since they have personnel with a high technical level who make international comparisons with other countries to remedy the shortcomings of data. Chapter 7 recommends strategies for data collection

5. Legal advice

Once the proposal is ready, it is sent to the MTC’s legal office so that it verifies, on one hand, the requirements of legislative technique and, on the other, that it does not opposes another legal instrument.

6. Pre-publication of the proposal

Once the legal office draws up and reviews the proposal, the MTC pre-publicises it in the Official Gazette El Peruano and on its transparency website, based on the Supreme Decree DS-001-2009-JUS. Its Article 14 states the obligation of publishing general regulatory proposals in El Peruano, on the websites or in any other medium for a minimum period of thirty days.

The main area of opportunity of the pre-publication of regulatory proposals lies in their legal basis, since it does not mentions any obligation regarding the handling of public comments. That is, the ministries are not obliged to publish the comments or to reply to them; although the MTC does so occasionally.

7. Review by the General Secretariat

Once the final version of the proposal is available, the General Secretariat of the MTC conducts a final review to analyse the coherence of regulation with the regulatory framework in force of both the general administration and the ministry itself.

8. Submission and approval by the CCV

The CCV must analyse and approve if the proposal is a multisectoral regulation. The relevant vice-ministry has to send it to it.

9. Publication of the regulation

Once the CCV approves it, if it is a multisectoral regulation or, the MTC sends it directly, the proposal is published in the Official Gazette El Peruano. In the case of Ministerial Resolutions, for law-level regulation, the Ministry has to follow the process to send it to the Congress.

Lack of RIA practices

In the process to prepare the regulation, the MTC does not performs an analysis of the measures necessary to ensure compliance with regulations, nor of the measures taken for monitoring and evaluating the regulation.

Likewise, before implementing the pilot committee to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals introduced in January 2017, in the process to prepare regulations the MTC does not perform an analysis of alternatives to the regulation.

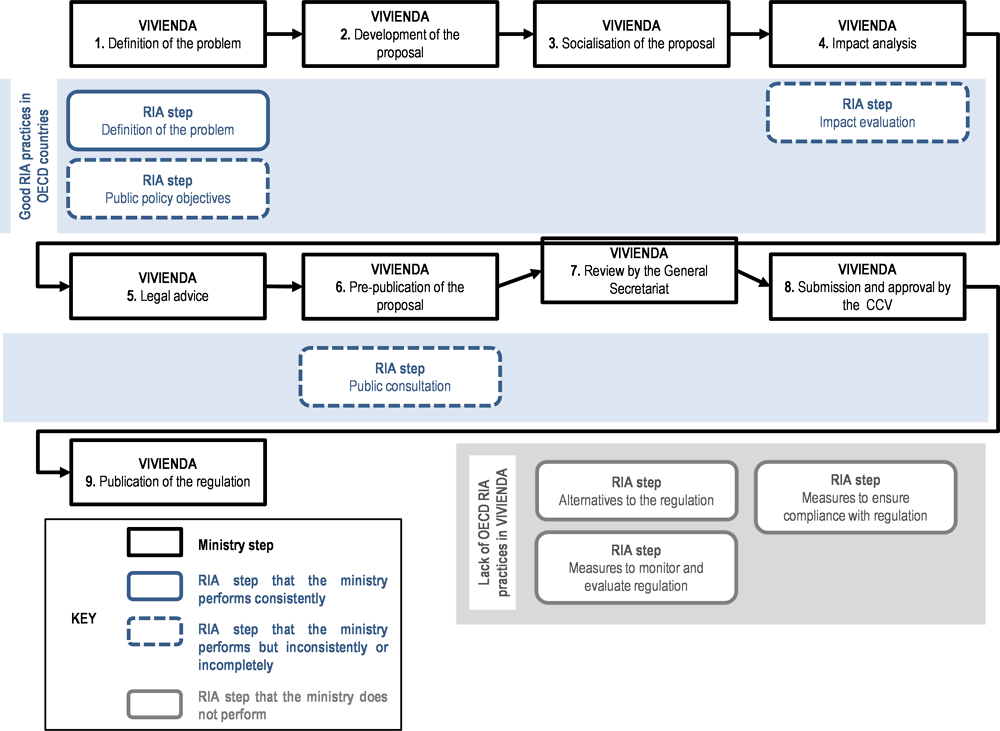

Process to issue regulations in the Ministry of Housing, Construction and Sanitation

Figure 5.5 shows the process to issue regulations identified in the Ministry of Housing, Construction and Sanitation (VIVIENDA).

1. Definition of the problem

The first step identified in VIVIENDA is the definition of the problem. There is not a systematised process in VIVIENDA to identify the problem, such as a checklist of questions or criteria. Nevertheless, enough evidence was found in the cases reviewed (see Chapter 2) to conclude that the definition of the problem is consistent with the RIA practices.

There are efforts in VIVIENDA to define public policy objectives. In general, the objectives are described in the explanatory statement of the regulations. There are still, however, important areas of opportunity to provide a clear definition of the public policy objective.

2. Development of the proposal

After the identification of the problem, VIVIENDA draws up the regulatory proposal in the competent division according to the subject matter.

Socialisation of the proposal

Once VIVIENDA prepares the project, it is subject to a socialisation stage, where other directions or agencies make comments on the proposal. The socialisation of the proposal is a non-standardised process and the comments received are not available to the public. However, when the matters are responsibility of this ministry and they affect different levels of government – such as urban planning – , VIVIENDA must socialise the regulatory proposal with, for instance, municipalities. The latter promotes the regulatory co-ordination at subnational level.

4. Impact analysis

After socialising the proposal with the areas and public entities interested in the subject, VIVIENDA carries out an impact analysis. Before January 2017, MTC did this analysis occasionally and unsystematically, there was no monitoring of its compliance unless it was a multisectoral regulation and the CCV had to review it; moreover, there was not always an impact analysis.

As of January 2017, the MEF, the MINJUSDH and the PCM created a committee – as a pilot programme – to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals. This committee advises the regulation-issuing bodies on how to perform it, on a case-by-case basis, although there are no formal guidelines.

On very few occasions, VIVIENDA does a quantitative impact analysis. Although it carries out a qualitative one, it is not performed systematically. Moreover, there is not a technical unit that is specifically in charge of conducting these analyses, but rather the same units that draw up the regulations are the ones that do so. Therefore, the level and thoroughness of that task depends on each of them.

5. Legal advice

Once the regulatory proposal is ready, it is sent to the legal advice office, which will verify it meets the requirements of form and legislative technique, and that it do not oppose any other previously existing regulation.

6. Pre-publication of the proposal

Once the legal office draws up and reviews the proposal, VIVIENDA continues with the pre-publication in the Official Gazette El Peruano and on its transparency website, based on the Supreme Decree DS-001-2009-JUS. Its Article 14 states the obligation of publishing general regulatory proposals in El Peruano, on the websites or in any other medium for a minimum period of thirty days.

The main area of opportunity of the pre-publication of regulatory proposals lies in their legal basis, since it does not mentions any obligation regarding the handling of public comments. That is, the ministries are not obliged to publish the comments or to reply to them, and although VIVIENDA does so occasionally, it is not a common practice.

7. Review by the General Secretariat

After the pre-publication of the proposal, the final version of the proposal is drawn up and the General Secretariat of VIVIENDA conducts a final review to analyse the coherence of regulation with the general administration and the ministry itself.

8. Submission and approval by the CCV

If it is a multisectoral regulatory proposal, the CCV must analyse it for its approval.

9. Publication of the regulation

If it refers to multisectoral regulation, once the CCV approves it, the proposal is published in the Official Gazette El Peruano. In the case of Ministerial Resolutions, for law-level regulation, the Ministry has to follow the process to send it to the Congress.

Lack of RIA practices

In the process to prepare the regulation, VIVIENDA does not performs an analysis of the measures necessary to ensure compliance with regulations, nor of the measures taken for monitoring and evaluating the regulation.

Likewise, before implementing the pilot committee to review the impact analysis of regulatory proposals introduced in January 2017, in the process to prepare regulations VIVIENDA does not performs an analysis of alternatives to the regulation.

General evaluation of the process to issue regulations in Peru

In general, the process for issuing regulations within the five selected ministries is virtually the same. The most important exception on the Ministry of Environment (MINAM), which performs a deeper consultation process that observes good RIA practices. While, in the other ministries, carrying out the process depends on the type of regulation and its relevance.

Lack of a standardised process with legal basis

The processes described before that focuses on the period 2014-16 are the ones the Ministries use to issue regulation. However, its use is a non-standardised practice, for there is not a specific instrument of regulatory policy that supports them – even though they exist some institutions and legal practices. In particular, in the process identified, only four steps have a legal basis:

-

Impact analysis

-

Pre-publication of the proposal

-

Submission and approval by the CCV (in the case of multisectoral regulation)

-

Publication of the regulation

It is evident that in this process there is no formalised oversight nor accountability regarding the way of issuance of the regulation, at least from a comprehensive point of view. As of January 2017, the government set up a pilot programme to perform an impact analysis, but it does not have yet a legal basis nor is mandatory.

The practice of any process to promote quality in regulation is at risk for this lack of formality, as it is very easy to eliminate these practices or ignore the established criteria, regardless of their technical strength.

The lack of formality also threatens the standardisation and transversality of the regulatory policy. Without the legal obligation of implementing the RIA and no supervisory body that enforces it, the purpose of promoting quality in regulation is limited. In fact, the incentives to officials so they observe the RIA discipline are not the same under specific legal obligations than without them.

The lack of formality increases the risk of regulatory capture because there are no institutionalised mechanisms that confront the validity, relevance, and necessity of the regulation. The lack of accountability in a controlled and transparent process of ex ante evaluation of the regulations creates a greater risk that actors have a negative influence on the regulation. Promoting regulations (via public consultation processes) is a mechanism of public action to be accountable and improve the regulatory proposal. However, if this process is not conducted under specific criteria, there is a greater risk of negative influence.3

On the other hand, in 2017 the process of elaboration and evaluation of the RQA began to work. Its objective is to identify, eliminate and/or simplify administrative procedures that are unnecessary, inefficient, unjustified, disproportionate, redundant or not adequate to the applicable regulatory framework. The RQA also aims to identify and reduce the administrative burdens of administrative procedures (see Chapter 4 for a more detailed description of the RQA).

In this process, Executive Branch entities seeking to issue or modify regulations and containing administrative procedures must prepare the RQA and submit it to the CCR chaired by PCM. The RQA must contain sufficient elements to enable the CCR to evaluate the legality, necessity, effectiveness, and proportionality of the administrative procedure (see Box 5.2 for more detail). The CCR may issue a binding report requesting modifications, validating administrative processes, or ordering their elimination if they are not validated.

The presentation and evaluation of the RQA is a stage prior to the publication of the regulation. The RQA introduces an element of discipline in the drafting of regulations in Peru, which contributes to the creation of a RIA system.

According to the Manual for the Application of Regulatory Quality Analysis, the public entities of the executive branch of Peru (EPPE) must analyse the principles of legality, necessity, effectiveness and proportionality of administrative procedures (AP) in order to perform the RQA:

Legality

-

Determine the nature of the AP in order to categorise whether it produces legal effects on the interests, obligations or rights of those administered.

-

Identify the competence of EPPE, to determine whether the competence is exclusive or shared with other levels of government.

-

Identify or establish the legal basis of the AP and its requirements.

Necessity

-

Identify the problem that the regulation linked to the AP intends to solve and the scope in which this problem occurs, if it is at the national, regional and/or local level.

-

Determine AP’s specific objective and the contribution it will bring on solving the problem. The specific objective must be achievable, relevant and measurable over time.

-

Identify what the possible risks would be if the AP is removed or the new procedure proposal is not approved.

-

Analyse whether there is an alternative that replaces the AP.

Effectiveness

-

Analyse that each one of the requirements demanded contribute effectively to reach the object of the AP.

-

To detect the requirements that are unnecessary or unjustified to the objective of the AP, for its later elimination.

Proportionality

-

Analyse that each one of the requirements demanded contribute effectively to reach the object of the AP.

-

Detect the requirements that are unnecessary or unjustified to the objective of the AP, for its later elimination.

In addition, EPPE must estimate the monetary and time costs of each of the requirements of the AP, so that the application used to deliver the RQA produces an estimate of the administrative burden of the AP.

Source: Ministerial Resolution No. 196-2017-PCM approving the Manual for the Application of Regulatory Quality Analysis (RM. 196 2017-PCM).

Definition of the problem and public policy objectives

According to the evidence showed of the period 2014-16, in Peru is recognised that on the issuance of regulation it is reflected the government’s intention to solve a problem that has previously been identified. However, it is not common to set explicitly the public policy objective when addressing the identified problem.

It will be necessary to determine whether with the introduction of the RQA, the definition of the problem and of the public policy objectives in the regulatory issuing process is more effective. As indicated in Box 5.1, the analysis of the principles of necessity, effectiveness and proportionality can contribute to it.

Alternatives to the regulation and impact analysis

According to the evidence showed of the period 2014-16, in Peru there are initial efforts to carry out an impact evaluation of regulations, but much remains to be done to systematise this practice and raise the quality of the exercise.

The bylaw of the Congress lays down the obligation to perform cost-benefit analyses in draft bills. This bylaw indicates, “bills must include an explanatory statement detailing its rationale, the effect of the life of the regulation proposed on national legislation, including a cost-benefit analysis of the future legal rule.” In practice, however, it is only included an analysis of the possible direct costs or of budgetary burdens that could be incurred by the State to carry out the proposal. It are mentioned neither the costs for the industry nor for the consumers.

Apart from the legal obligations of conducting an appropriate impact analysis, ministries face obstacles to carry it out. One of the most important problems to conduct those analyses is the availability of information or, if applicable, the lack of a methodology to obtain or produce it.

The impact evaluation should be prepared for all the identified alternatives to the regulation. Doing so would ensure that the regulation chosen be the most appropriate by producing the greatest benefit to society. In Peru, it is not necessary to carry out systematically an identification of alternatives.

With the introduction of the RQA as of 2017, it is expected that with the analysis of the principles of necessity, effectiveness, and proportionality, government entities would identify alternatives to regulation more effectively. In addition, since entities are required to calculate the costs of requirements, this can contribute to the preparation of a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis.

Notwithstanding the advantages that the RQA provides compared to the situation prevailing prior to its introduction, the RQA does not include requesting a cost-benefit analysis of the regulations that are intended to be issued or modified. In a RIA system the cost-benefit analysis, even qualitatively, is intended to contrast the benefits of the regulation as a whole against the costs that would be generated by its adoption.

Compliance with regulation

When a regulation is issued, it is necessary that civil servants identify in advance the mechanisms that are to be established, as well as the resources needed to ensure that the provisions stated therein will be observed. These could include oversight mechanisms, fines or other types of incentives. Although in Peru for the 2014-16 period some cases consider this type of mechanisms when issuing regulations, it is not a systematised practice.

Monitoring and evaluation

On the period 2014-16, Peru did not previously establishes indicators to measure the level of accomplishment of the public policy objectives intended to be reached, nor of the mechanisms to evaluate on an ex post basis if those objectives were achieved.

Public consultation

The public consultation of regulatory proposals is a key element that is constantly used to improve or narrow down the definition of the problem, obtain relevant information, identify stakeholders, and smooth out the process of adopting the new regulation by the actors involved. Currently, public consultation in Peru is called pre-consultation; and it is only used intermittently.

On the period 2014-16, the activities carried out by the MINAM after socialising the proposal stand out, namely, the creation of a matrix of comments, meetings with the commentators, and redeveloping the regulatory proposal. These activities should be systematically implemented in all the institutions from the central government of Peru. As well as the practice established in VIVIENDA of consulting the draft proposal among the different levels of government.

With respect to the RQA that became operational in 2017, its development and evaluation process does not include provisions to address the sections of regulatory compliance, monitoring and evaluation, and public consultation, which should be part of a RIA system.

Chapter 7 includes recommendations for adopting each of the essential stages of the RIA system in the process to issue regulations in Peru.

References

[2] OECD (2016), Regulatory Policy in Peru: Assembling the Framework for Regulatory Quality, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260054-en.

[1] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

Notes

← 1. Legislative Decree 1310 introduced the ACR evaluation procedure. It was published on December 30, 2016, and its provisions entered into force the following day.

← 2. The description and analysis included in this chapter refer to the practices performed before the beginning of the RIA pilot program, introduced in January 2017. In any case, the conclusions of this chapter are important to reform that pilot programme.

← 3. Peru’s Energy and Mining Investment Supervisory Agency (OSINERGMIN) and Peru’s Public Transport Infrastructure Investment Supervisory Agency (OSITRAN) have taken action to implement RIA. Both OSINERGMIIN and OSITRAN have published manuals for the development of RIA and are already using them in practice.