copy the linklink copied!Policy framework, structure of the report and assessment process

copy the linklink copied!The Small Business Act for Europe as underlying policy framework

The SME Policy Index is a benchmarking tool for assessing and monitoring progress in the design and implementation of policies for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) against European Union (EU) and international good practice. It is structured around the ten principles of the EU’s Small Business Act for Europe (SBA),1 which provides a wide range of pro-enterprise measures to guide the design and implementation of SME policies.

While there are a number of other indices that assess the business environment in the countries of the EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP),2 the SME Policy Index adds value through its holistic approach to SME development policies, providing policy makers with a single window through which to observe progress in their specific areas of interest. Over the years, the SME Policy Index has established itself as a change management tool used by participating national governments to identify priorities and obtain references for policy reform and development.

The index was developed in 2006 by the OECD, in partnership with the European Commission, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the European Training Foundation (ETF). Since then, it has been applied regularly in an expanding geographical footprint, that now covers almost 40 economies in 5 regions: the EaP countries, the Western Balkans and Turkey, the Middle East and North Africa, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and Latin America and the Caribbean.

Building on the strengths of the Index and in order to address some of its weaknesses (Table 1) and increase its impact, this 2020 edition goes beyond the analysis of areas covered by the SBA to capture other relevant policy priorities hindering SME development (i.e. competition, contract enforcement and alternative dispute resolution, and business integrity), while broadening the scope of issues covered within the core policy areas. Thus, the 2020 SME Policy Index includes:

-

a new pillar assessing level-playing-field conditions (including competition, contract enforcement and business);

-

eight new sub-dimensions3 covering policy aspects that were not included in the previous cycle;

-

extended and amended sub-dimensions to collect more in-depth information;

-

an increased focus on the economy’s performance and implementation of SME policies, as well as a sectoral focus box for each country;

-

in-depth private sector feedback collected during focus groups to gauge the outcome of policies; and

-

greater involvement of national statistical offices in the data collection process and more-extensive collection of relevant statistical data.

copy the linklink copied!The 2020 SBA assessment framework and structure of the report

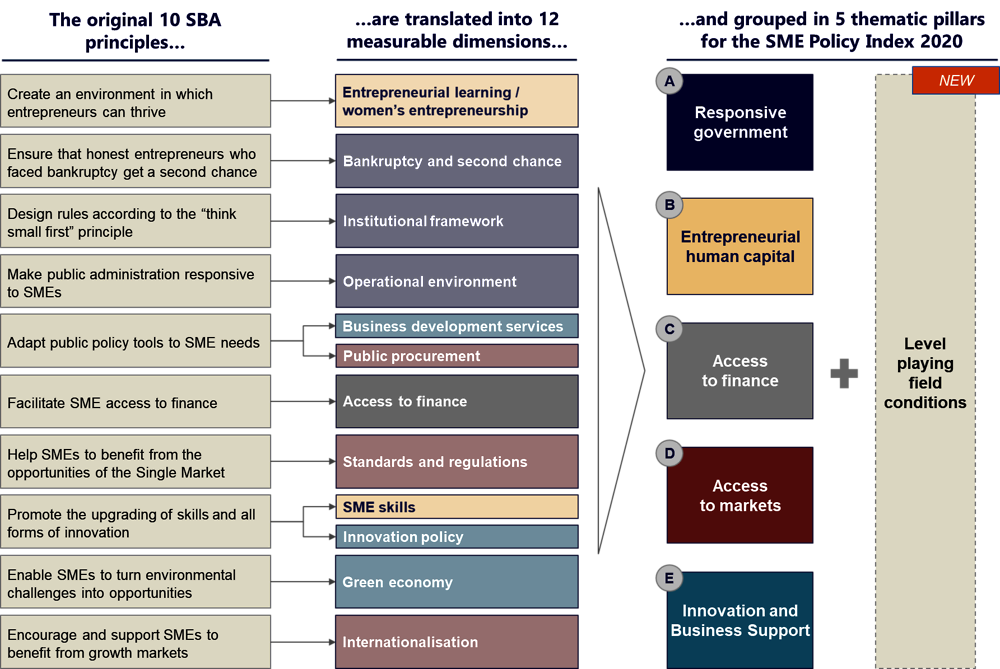

The SME Policy Index links the 10 SBA principles to 12 measurable dimensions, which are further broken down into sub-dimensions and thematic blocks, each of which captures a number of indicators (Figure 1). A new structure has been introduced to the presentation of the Index to help the reader navigate the world of SME policy by following the entrepreneurial journey from a public policy viewpoint.

While maintaining overall continuity and comparability of content with previous editions of the Index, this report features several changes (see below and Box 2) and structures the results of the SBA assessment around five thematic pillars and a level-playing-field pillar. Each pillar deals with core questions worthy of governments’ attention when designing policies conducive to SME development:

-

Responsive government: Is the overall operational environment conducive to business creation and risk-taking? Is the framework for SME policy responding to the needs of small and medium entrepreneurs?

-

Entrepreneurial human capital: Are the formation of entrepreneurship key competence and the development of SME skills part of the public policy setting? It is approached in a gender-sensitive way, supporting women’s entrepreneurship?

-

Access to finance: How available is external financing for start-ups and SMEs? Have specific policy instruments been introduced to make it easier and cheaper for small entrepreneurs to obtain funds to start and grow their businesses?

-

Access to markets: Are SMEs able to sell their products and services to clients in domestic and foreign markets? Can public policies make it easier for small entrepreneurs to enter new markets?

-

Innovation and Business Support: Can SMEs obtain advice and technology to remain competitive and increase their productivity? Is the government fostering a more innovative SME sector?

These 12 policy dimensions are further broken down into 34 sub-dimensions that capture the critical policy elements in each area (Table 2).

In addition to the five pillars, this report complements for the first time the SBA assessment with an analysis of selected dimensions of the business environment that are critical to the creation of a level playing field for all enterprises, regardless of size and ownership status.

This “Level playing field” pillar, which is not being scored to maintain the consistency and comparability of the SBA assessment, includes three dimensions that analyse 1) the extent to which the competition authority is fulfilling its mandate to ensure fair competition for all companies; 2) the efficiency of the existing contract enforcement system and alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms; and 3) the degree to which business integrity policies are in place and promoted by the government in order to prevent corruption in the private sector (Table 3).

This report contains dedicated thematic chapters, and corresponding sections within each country chapter, for each of the above-mentioned dimensions.

Although this report is structured along the 12 SBA assessment dimensions (which are analysed in different thematic pillars and respective dimensions in the six country profiles), they should not be seen as stand-alone elements, since they interact with and complement each other in many ways. For instance, the Access to finance dimension is intrinsically linked to many of the other dimensions because it is the fundamental prerequisite for the development of SMEs. Easy access to finance can provide SMEs with the resources necessary to invest in Entrepreneurial learning and SME skills as well as in Innovation and Business development services. Those inputs can enable enterprises to increase productivity and introduce innovation-oriented practices – which, in turn, are crucial to their competitiveness and entry into new (domestic) markets through Public procurement and Internationalisation of their businesses. However, access to new markets can only be achieved if businesses are given the opportunity to grow and thrive, which depends on favourable level-playing-field conditions and a solid and effective Institutional and regulatory framework contributing to a well-functioning Operational environment.

The tight interconnection among all the pillars and dimensions results in the necessity for policy makers to look at the broader picture. Focusing on achieving results in a single dimension or area is therefore insufficient; reform efforts in one area ought to be backed by progress and a solid foundation in all the other dimensions, symbiotically achieving success in supporting SMEs.

copy the linklink copied!Supplementary data

In addition, the 2020 SBA assessment aims to better gauge policy implementation and outcomes by involving the private sector directly in the assessment process. To this end, the OECD conducted two private sector focus groups in each of the six EaP countries to discuss the main constraints on doing business for SMEs in terms of the six pillars of the assessment, while receiving feedback on recent policy developments.

Moreover, this assessment round has introduced a sector-specific section in the country chapters, identifying major developments and SME policy constraints in a given sector with high export potential. The choice of country-specific sectors was based on the findings of the International Trade Centre (ITC), which is currently implementing the EU4Business initiative “Eastern Partnership: Ready to Trade” – a project that helps SMEs from EaP countries integrate into global value chains and access new markets, with a focus on the EU (See Box 1).

The “Eastern Partnership: Ready to Trade” initiative is financed by the European Union under the EU4Business initiative and implemented by the International Trade Centre in co-operation with CBI.*The project budget is EUR 6 million and covers the period 2017-20. The initiative assists exporting and export-ready SMEs from six Eastern Partner countries in producing value-added goods in accordance with international and EU market requirements, and linking them to international markets, with focus on the EU.

The project targets different sectors in different countries. It supports the agribusiness sector in Armenia and Azerbaijan (processed and dried fruit and vegetables, and herbal teas), as well as in Georgia (juices, processed hazelnuts, dried fruits and tea) and Ukraine (berries), and finally the apparel sector in Belarus and Moldova.

In particular, SMEs benefit from:

-

Increased awareness of international and EU market access requirements;

-

Advisory services, coaching and training in improved productivity, packaging marketing, branding, quality management and food safety, e-commerce, logistics, etc., to foster competitiveness;

-

Business linkages with EU buyers through trade fairs, study tours and business-to-business networks; and

-

Improved services provided by business support organisations.

So far, the following results have been obtained:

-

Roadmaps have been developed for selected value chains in each country;

-

The capacities of SMEs have been strengthened to increase the value-added production and improve competitiveness;

-

The capacities of sectoral Business Support Organisations (BSOs) have been enhanced to provide SMEs with quality and relevant services along the value chains; and

-

Business linkages have been created for SMEs to expand their sales in international markets and value chains, in particular the EU.

* The Centre for the Promotion of Imports from developing countries, established in 1971, contributes to sustainable and inclusive economic development in developing countries through the expansion of exports from these countries to Europe. See https://www.cbi.eu/about.

Source: EU4Business website, http://www.eu4business.eu/programme/eastern-partnership-ready-trade-eu4business-initiative.

As for the sectors, agribusiness was chosen by ITC as a focus for Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Ukraine, while the apparel sector was analysed in Belarus. For Moldova, in order to exploit internal knowledge related to an ongoing OECD project, a different sector from the initial ITC one was chosen, and agriculture and food-processing sectors were analysed instead. The sectoral analysis draws heavily on desk research and analysis, as well as on sectoral focus group (one focus group per country) findings. It does not aim to provide a comprehensive picture of SME challenges in selected sectors, but rather to present key challenges and highlight priority areas for further policy improvements. The sectoral analysis concludes the SBA assessment section of each country chapter and is represented in a concise manner as a box on SME perspectives.

Box 2 summarizes the new changes to the 2020 assessment framework.

The partner organisations agreed, following consultations with the SBA co-ordinators in the six EaP countries in 2018, to introduce certain improvements to the 2020 SME Policy Index. The objective of these changes was threefold:

-

a. To broaden the scope of the assessment and allow for an evaluation of the overall business environment conditions taking into consideration relevant policy priorities – competition, contract enforcement and business integrity – which contribute to the creation of a level playing field for all enterprises, regardless of size and ownership type. This additional part of the report has not been scored to maintain the consistency and comparability of the SBA assessment.

-

b. To enrich the qualitative assessment through a broader analysis of quantitative indicators. The inclusion of statistics, including the data collected for the OECD SME financing scoreboard and data from national statistical offices, provides additional context for the policy assessment and allows for better comparison and benchmarking with EU and OECD countries.

-

c. To introduce a sectoral focus has been introduced in the country chapters, by identifying sector-specific policy constraints faced by SMEs in each country. This has been achieved through a more consistent involvement of the private sector in the assessment process – in the form of private sector (sectoral) focus groups, regular consultations, and the participation of the private sector in SBA public-private working group meetings throughout the assessment process.

The modifications introduced in 2018 have preserved the fundamental features of the SME Policy Index and the core elements of the original methodology – including the multi-dimensional approach based on the 10 SBA principles, the intra-regional benchmarking focus, the participative assessment method, and the five-level scoring framework – so as to ensure comparability over time.

Pillar scores have been introduced when relevant without making changes to the scoring system of dimensions and sub-dimensions; score changes solely due to the introduction of new sub-dimensions are reflected in the country chapters and figures, when relevant.

copy the linklink copied!The 2020 SBA assessment process

The SME Policy Index is based on the results of two parallel assessments. First, a self-assessment, which consisted of completing a questionnaire and providing relevant evidence (including statistical data), was conducted by each of the six governments. In addition, the OECD and its partner organisations conducted an independent assessment that included inputs from a team of local experts, who collected data and information and conducted interviews with key stakeholders and private sector representatives.4

The final scores are the result of the consolidation of these two assessments, enhanced by further desk research by the OECD, ETF, and EBRD as well as consultations with government and private sector representatives during country missions.

Timing of the 2020 assessment

The 2020 SBA assessment was carried out between January 2018 and June 2020 in three phases:

Review of methodology and framework (January 2018 – September 2018): The methodology and assessment framework were updated in consultation with all partner organisations (European Commission, EBRD and ETF) and SBA co-ordinators. The assessment framework for the Level playing field pillar was developed and slight changes to the core SBA dimensions were introduced (see Box 2 and Annex A.). Introductory country missions were held throughout May-June 2018 to present the updated methodology, process and timeline of the assessment to key stakeholders expected to contribute to the assessment (governmental and private sector representatives, as well as international organisations and NGOs). The country missions were followed by the first Regional SBA Co-ordinators meeting in July 2018 in Brussels, which gathered representatives from all partner organisations and the six EaP governments to discuss and approve the updated assessment framework.

-

Data collection, evaluation and verification (October 2018 – June 2019): The EaP countries carried out a self-evaluation of their policy frameworks (via the assessment questionnaire and the statistical data sheet) and completed materials were sent to the OECD team. Upon the receipt of countries’ self-assessments, the OECD and partners conducted an independent assessment via extensive desk research and follow-up with relevant stakeholders in order to fill information gaps and resolve inconsistencies in findings. The assessment also benefitted from inputs by a team of local experts; and for the Entrepreneurial Human Capital pillar, focus groups were held to build on the self-evaluations. In-country reconciliation meetings were held throughout April-June 2019 to discuss and verify the SBA assessment findings by presenting them to key SME policy stakeholders, including representatives of ministries and government agencies, international donors, civil society, academia, NGOs, and business associations. In addition, sector-specific focus groups with businesses were conducted during this period to gather information for the sectoral analysis. In July 2019, the second Regional SBA Co-ordinators meeting took place in Paris, where the final results were presented, discussed, and endorsed.

-

Drafting, review, and publication (February 2019 – June 2020): OECD and partner organisations drafted country chapters that were sent to countries at the end of June in preparation of a Regional SBA co-ordinators meeting held on 2-3 July 2019. Following discussions and comments provided during the meeting, the country chapters were updated and sent to SBA co-ordinators for comments and feedback in early August, while the thematic pillars underwent internal reviews and adjustments. The report – SME Policy Index: Eastern Partner Countries 2020 – then underwent several internal reviews before being officially launched at OECD Eurasia Week in March 2020, in Tbilisi, Georgia. The publication will also be launched in the six EaP countries during dedicated dissemination events between March and June 2020.

copy the linklink copied!The Eastern Partnership and the Small Business Act for Europe

The 2020 SBA assessment was carried out in the context of the Eastern Partnership, the political framework of co-operation between the EU, its Member States and the six Eastern Partner countries. The policy framework used for the assessment is the SBA, the key policy tool for implementing SME policy in EU Member States.

The Eastern Partnership

Political framework

The Eastern Partnership (EaP) was launched in 2009 at a summit held in Prague. It is a political initiative joining the EU, its Member States and the Eastern European partners (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine) in an effort to promote political, economic and social reforms, bringing the EaP countries closer to the EU. The EaP supports and encourages reforms in the EaP countries for the benefit of their citizens. It is based on a shared commitment to international law and fundamental values – including democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms – as well as the market economy, sustainable development and good governance. The partnership is founded on mutual interests and commitments as well as shared ownership and mutual accountability. The Eastern Partnership creates the conditions for accelerating political association and deepening economic integration between the EU and the Eastern European partner countries. The Eastern Partnership is part of the EU Neighbourhood Policy.

The Association Agreements concluded in 2014, including those for Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTAs), have brought the relations between the EU and Georgia, the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, respectively, to a new level. These agreements constitute a plan of reforms that have already brought the partner countries closer to the EU by aligning their legislation and standards with the EU acquis. The EaP will continue to be inclusive by providing a more differentiated and tailored approach to relations with Armenia, Azerbaijan and Belarus, in line with their sovereign choices. On 24 November 2017 the EU and Armenia signed a Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA), which entered into provisional application on 1 June 2018 and aims at enhancing political relations and comprehensive economic co-operation. At the same time, the EU is also discussing a closer relationship with Azerbaijan that which reflects respective interests and values, and is deepening its critical engagement with Belarus.

The 2015 Riga Summit (European Commission, 2015[1]) concluded that co-operation within the Eastern Partnership should in future focus on: 1) strengthening institutions and good governance, 2) enhancing mobility and contacts between people, 3) developing market opportunities, and 4) ensuring energy security and improving energy and transport interconnections.

Moreover, EU Member States and EaP countries share a view that the EaP should focus on delivering tangible results to citizens. In response, the European Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) identified a set of 20 deliverables for 2020, first published in December 2016. The “20 Deliverables for 2020” document aims to identify concrete, tangible results for citizens as delivered by the EaP in the four priority areas agreed in Riga, on the basis of already existing commitments on both EU’s and Partner Countries’ side (European Commission, 2017[2]).

Multilateral track: Platform 2

The Eastern Partnership involves two complementary work streams: the bilateral and multilateral tracks. The numerous challenges which EaP countries share are jointly addressed through the multilateral track through co-operation, networking and the exchange of best practice. Multilateral co-operation work is guided by four thematic platforms, supported by various expert panels, flagship initiatives and projects. These platforms cover the following themes:

-

strengthening institutions and good governance (Platform 1)

-

economic development and market opportunities (Platform 2)

-

connectivity, energy efficiency, environment and climate change (Platform 3)

-

mobility and people-to-people contacts (Platform 4).

The Director-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR), EEAS and the DG for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs (DG GROW) of the European Commission co-ordinate and co-chair Platform 2. This platform covers a wide range of sectorial policies. Policies and planned activities include enterprise and SME policies; trade and trade-related regulatory co-operation linked to the DCFTAs; and co-operation over agriculture and rural development, statistics, harmonisation of digital markets, taxation and public finances, labour market and social policies, and macroeconomic and financial stability.

A dedicated Panel on structural reforms, financial sector architecture, agriculture and SMEs aims to develop a favourable business environment for SMEs in EaP countries – which are currently constrained by an inadequate regulatory and policy framework, a lack of advisory services, limited access to finance and a lack of interregional and international networking mechanisms. The Panel is directed towards government officials as well as business and SME associations. Support is offered under the umbrella of EU4Business in four priority areas:

-

Improving Access to Finance: The first priority area focuses on ensuring that SMEs in the Eastern Partner countries have adequate access to financing. It not only relates to the provision of loans per se, but also to the circumstances under which loans are provided – such as the interest rate applied, the currency in which the loan is issued, the collateral required, and the risk incurred by the SME borrower. In order to change such circumstances, the implementers of access-to-finance projects have set up a series of activities focusing not only on the demand side (i.e. SMEs), but also on the supply side (i.e. participating financial institutions, or PFIs). The EU4Business portfolio currently includes 17 programmes and projects under the priority area “Improving access to finance”. The SME Finance Facility project is one of the most relevant in this area and it combines loans from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), and the KfW (Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, German government’s development bank) with EU grant resources, to support SME lending in the Eastern Partnership region.

-

Strengthening Regulatory and Policy Framework: SMEs are often faced with unnecessary barriers such as red tape. This leads to frustrated entrepreneurs, who, in the worst cases, may even give up. To address these barriers, the EU4Business Initiative seeks to improve the transparency and cost-efficiency of administrative regulations through the improvement of SME policies and adoption of legislation which is in line with the Small Business Act. Projects and programmes under this second priority area are focused mainly on supporting governments and BSOs in developing coherent policy reform plans, SME strategies and legislative proposals. The World Bank’s “Strengthening Auditing and Reporting in the Countries of the Eastern Partnership” (STAREP) programme aims to help participating countries both to improve their frameworks for corporate financial reporting and to raise the capacity of local institutions to implement these frameworks effectively.

-

Improving Knowledge Base and Business Skills: The third area of priority focuses on ensuring that the initiative’s beneficiaries possess the knowledge and skills necessary for their SMEs to thrive. Projects and programmes in this area focus on increasing SME investment readiness and making SMEs more attractive to investors by improving their knowledge and business skills. The support provided covers a wide variety of topics, such as improving management effectiveness and market performance, improving financial management and reporting, understanding quality management and existing certifications. Most of the EU4Business projects in this area are targeted at specific countries or specific areas (e.g. rural areas). One of the principal programmes is the EBRD “Advice for Small Businesses” initiative, which aims to promote good management in the SME sector by providing technical assistance to individual enterprises, helping them to grow their businesses.

-

Improving Access to Markets: The last priority area of the EU4Business Initiative focuses on enabling SMEs to go beyond their geographical location by providing them with expansion opportunities, not only at the national/regional level but also internationally. The provision of training to SMEs in how to comply with DCFTA provisions, product standards and certifications in the European Union market, dealing with trade barriers, etc., all ultimately leads to greater internationalisation and investment opportunities, as it makes businesses ready and able to receive foreign direct investment (FDI). The ITC’s “Ready to Trade” initiative, which is one of the most relevant EU4Business projects in this area, seeks to help SMEs from Eastern Partner countries integrate into global value chains and access new markets, with a focus on the European Union (EU). (See Box 3 in Chapter 5).

For more information, please see the EU4Business website (www.eu4business.eu).

The SBA assessment is a key tool for improving the business environment for SMEs and businesses in EaP countries, as well as strengthening institutions and good governance. These three aspects are priorities for the future work of the EaP, as outlined in the Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit in Riga (European Commission, 2015[1]). The SBA assessment is one of the Panel’s key projects. The Panel also follows up on the implementation of the SBA assessment recommendations and policy roadmap and measures progress.

The SBA assessment project is implemented within the EU4Business Initiative. EU4Business is an umbrella initiative that covers all EU support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the region of the Eastern Partnership which brings together the EU, its member states and six partner countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. It breaks down barriers SMEs face in their progress, such as limited access to finance, burdensome legislation and difficulties entering new markets, with finance, support and training, to help them realise their full potential. EU4Business support is delivered together with other organisations such as the EBRD and the EIB.

Small Business Act for Europe: A key policy tool for EU Member States

SMEs are the backbone of Europe's economy. They represent 99% of all businesses in the EU. Between 2010 and 2014, they created around 85% of new jobs and provided two-thirds of all private sector employment. The European Commission (EC) considers support for SMEs and entrepreneurship as key for ensuring economic growth, innovation, job creation, and social integration in the EU.

The SBA, which was adopted in June 2008, reflects the EC's recognition of the central role of SMEs in the EU economy. It aims to improve the approach to entrepreneurship in Europe, simplify the regulatory and policy environment for SMEs, permanently anchor the “Think Small First” principle in policy making, and remove the remaining barriers to SME development (European Commission, 2008[3]). Built around ten principles and several concrete policy actions to implement them, the SBA invites both the EC and EU Member States to tackle the obstacles that hamper SMEs’ potential to grow and create jobs. The main priorities of the SBA are: 1) promoting entrepreneurship; 2) reducing the regulatory burden; 3) increasing access to finance; and 4) increasing access to markets and internationalisation.

The SBA Review, launched in February 2011, was a major landmark in tracking the implementation of the Small Business Act. It aimed to integrate the SBA with the Europe 2020 strategy (European Commission, 2010[4]). This review presented an overview of progress made in the first two years of the SBA, set out new actions to respond to challenges resulting from the economic crisis, and proposed ways to improve the uptake and implementation of the SBA through a clear role for stakeholders – with business organisations on the front line.

Within the EU, the SME Performance Review is one of the main tools used by the EC to monitor and assess countries’ progress annually in implementing the SBA. The review brings in comprehensive information on the performance of SMEs in EU Member States and other countries participating in the EU's dedicated programme for SMEs – COSME (programme for the Competitiveness of Enterprises and SMEs; Box 3). It consists of two parts – an annual report on European SMEs, and SBA country fact sheets. The SBA fact sheets assess national progress in implementing the Small Business Act, while the fact sheets focus on indicators and national policy developments equivalent to the SBA’s 10 policy dimensions.

The SME Performance Review, as well as other actions supporting the implementation of the SBA in EU Member States, are undertaken through the EU’s programme for the Competitiveness of Enterprises and Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (COSME). The programme started in 2014 and will run until 2020, with DG GROW responsible for its implementation. COSME’s objectives are as follows:

-

improving the framework conditions for the competitiveness and sustainability of EU enterprises, including in the tourism sector

-

promoting entrepreneurship, including among specific target groups

-

improving access to finance for SMEs in the form of equity and debt

-

improving access to markets inside the EU and globally.

COSME is also open to non-EU Member States. Like most other EU programmes, it allows EaP countries to participate provided that a Protocol or a Framework Agreement on the general principles for the participation of the respective country in EU programmes is in place. Participation in EU programmes is meant to facilitate the political association and economic integration of partner countries.

References

[2] European Commission (2017), Eastern Partnership - 20 Deliverables for 2020. Focusing on key priorities and tangible results, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/swd_2017_300_f1_joint_staff_working_paper_en_v5_p1_940530.pdf.

[1] European Commission (2015), Joint Declaration of the Eastern Partnership Summit (Riga, 21-22 May 2015), http://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/21526/riga-declaration-220515-final.pdf.

[4] European Commission (2010), Communication from the Commission: Europe 2020 - A strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52010DC2020.

[3] European Commission (2008), Think Small First - A Small Business Act for Europe, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/small-business-act_en.

Notes

← 1. See https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/small-business-act_en.

← 2. Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine.

← 3. The eight new sub-dimensions are: 1) business licensing, 2) tax compliance procedures for SMEs, 3) bankruptcy prevention measures, 4) overall co-ordination and general measures, 5) SME access to standardisation; 6) Trade Facilitation Indicators; 7) use of e-commerce; and 8) policy framework for non-technological innovation. Please refer to Annex A for further details on methodology.

← 4. A cut-off date of 30 June 2019 was established for the assessment. Only policy developments and reforms implemented by that date were taken into account for the calculation of the Index. Reforms and policy developments that have taken place after that date (by September 2019) are reflected in the text.

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/8b45614b-en

© OECD, ETF, European Union and EBRD 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.