Chapter 1. Tackling Italy’s social and regional divide

Disparities in income and well-being in Italy are large, and follow regional lines more closely than in most OECD countries. Differences in employment rates, especially among women, explain much of regional disparities, while differences in labour productivity play a smaller but not negligible role.

These problems, long-standing and deep-rooted, are partly attributable to tax and benefit policies and labour market institutions, which discourage employment, especially of second earners in regions where wages and productivity are lower. The labour income tax wedge is high, curbing job creation, especially of low income jobs. At the same time, benefit policies offer little protection against poverty and labour market risks for many people. To redress this, the guaranteed minimum income scheme implemented in 2017 and 2018 and strengthened in 2019 through the Citizen’s Income is an important and welcome step. However, the success of this initiative will hinge on greatly enhancing job-search and training policies along with other social inclusion services. Fiscally sustainable reforms to tax and benefit policies should aim at maintaining progressivity, better supporting poor households, and encouraging labour force participation especially of low income workers, thus benefitting lagging regions.

Ineffective regional development policies and low efficiency of local public administrations in poorer regions contribute to regional disparities. Rationalising and improving coordination among the different bodies involved in regional development would make regional development policies more effective. Funds for regional development policies need to add to and not to substitute for those of ordinary administration. More effective regional development policies need to be flanked by initiatives aiming at raising the effectiveness of poorer performing local public administrations, thus enhancing the local provision of public goods and services, and better supporting disadvantaged households.

Italy’s large disparities in income and well-being follow regional lines

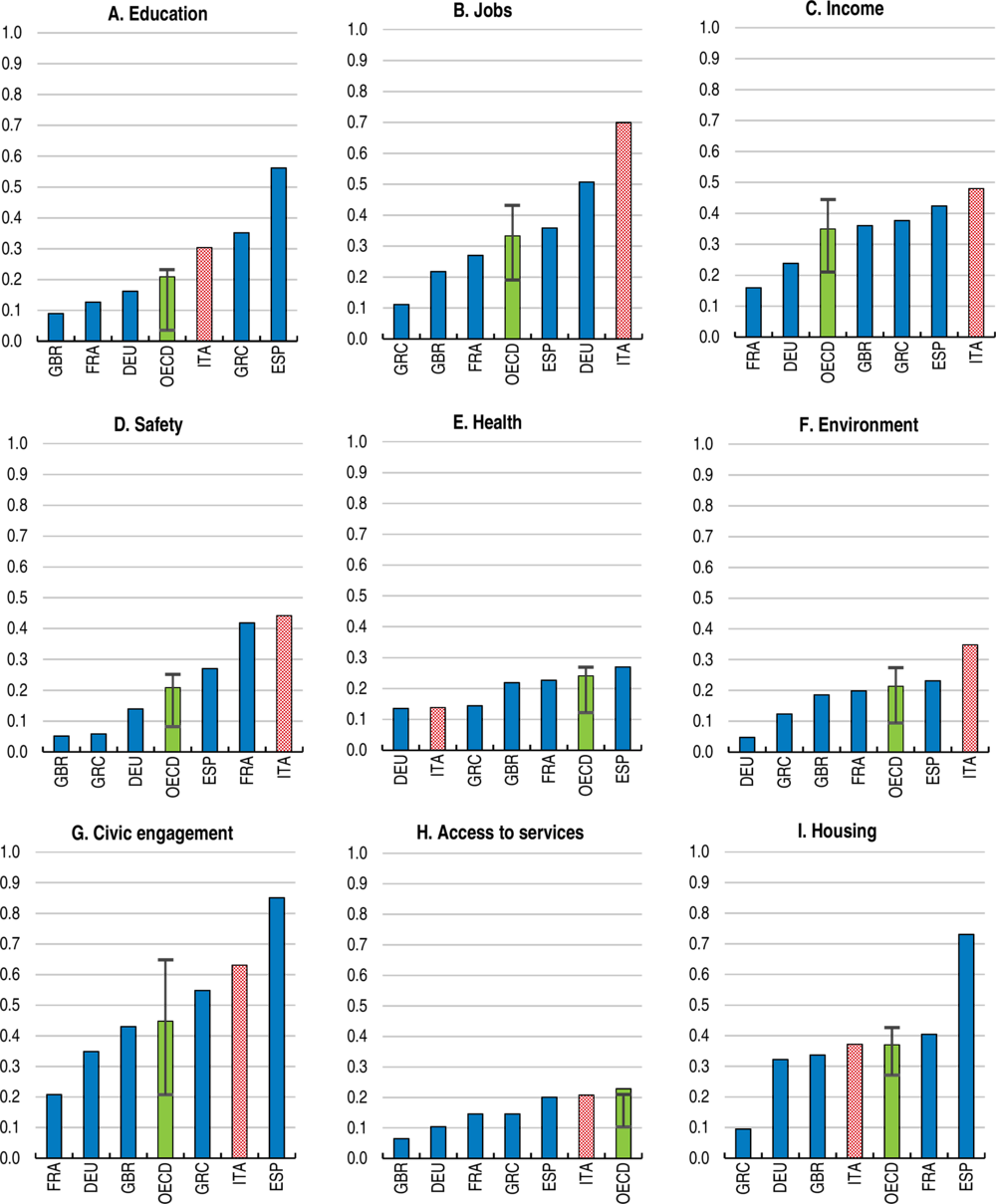

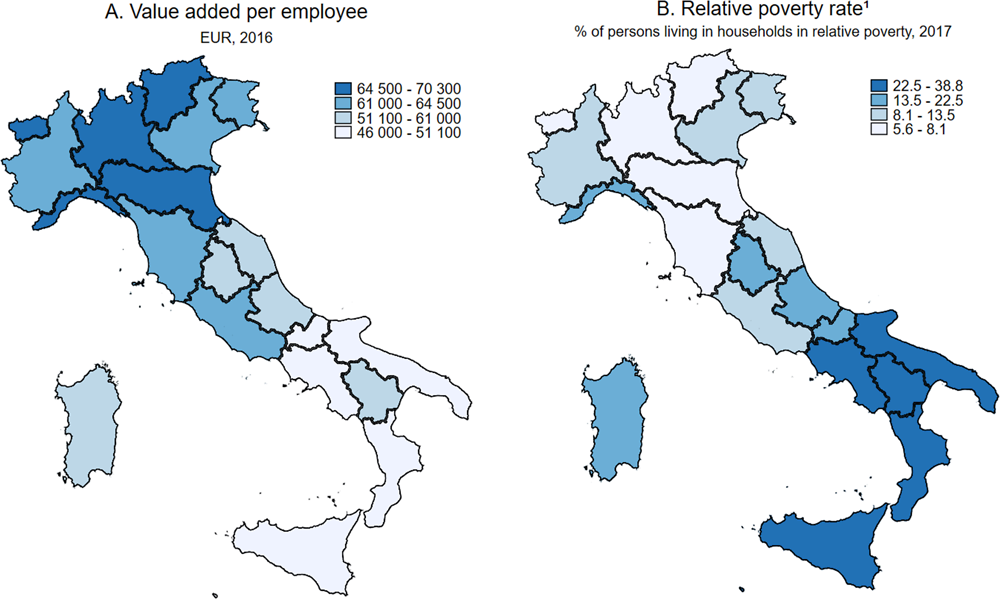

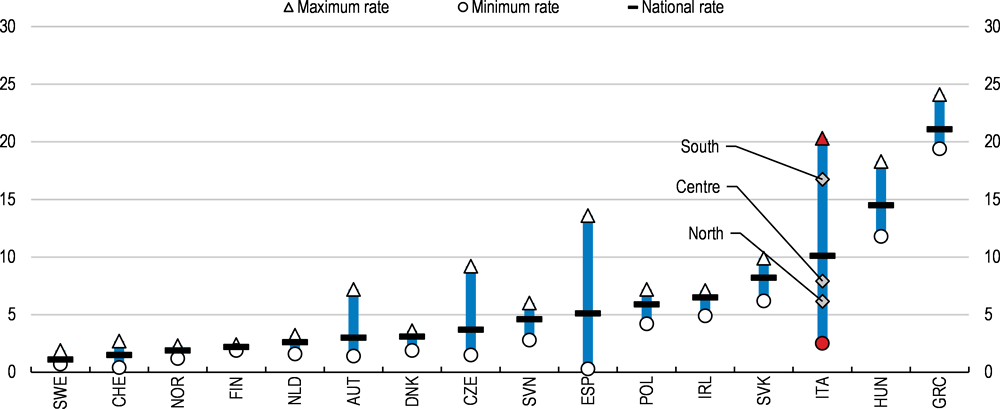

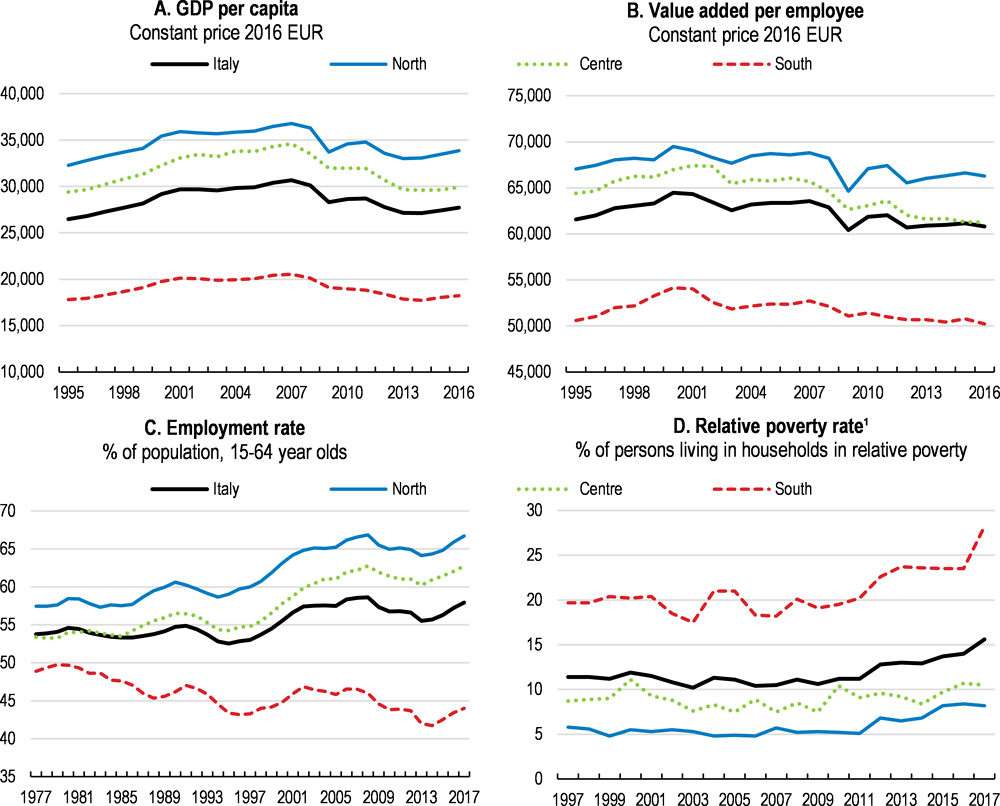

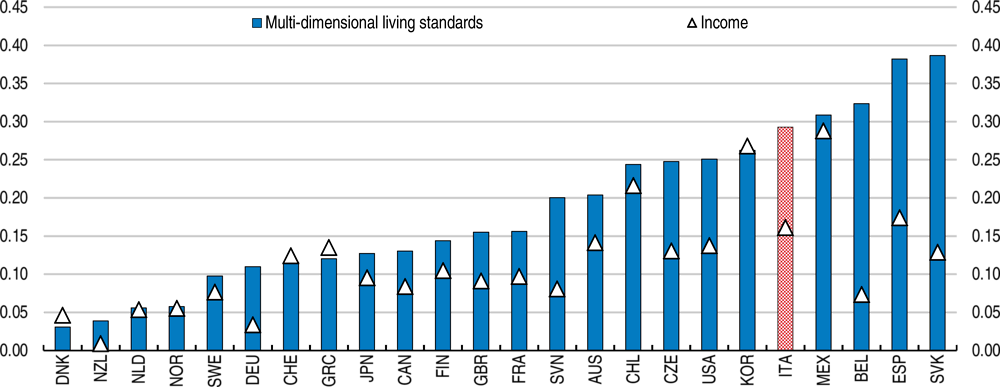

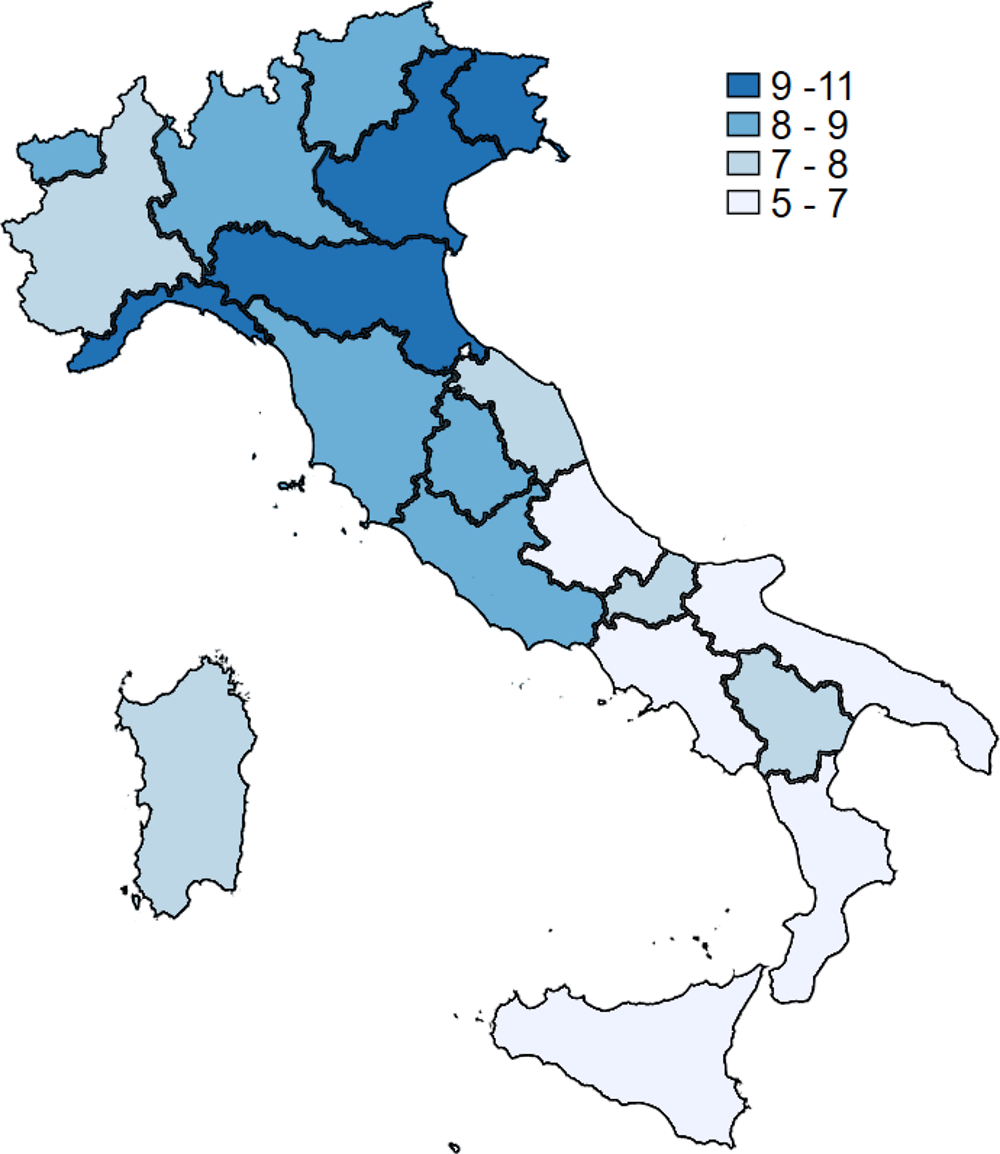

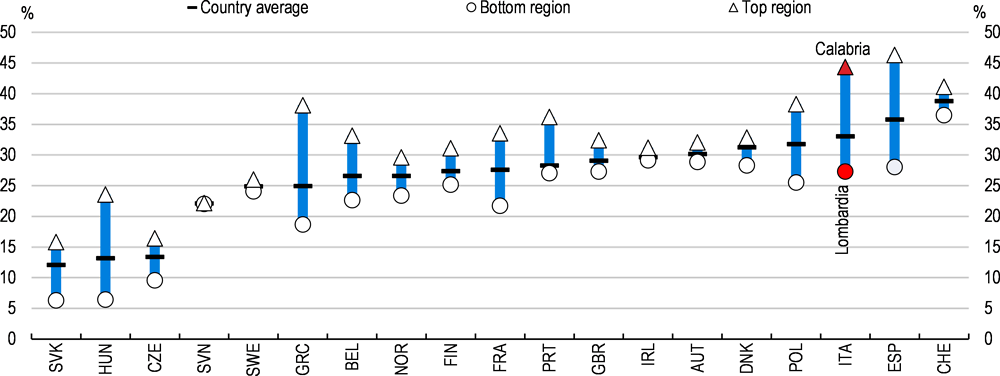

Italy’s social disparities are large. Italy’s well-being outcomes lag other OECD countries in several dimensions, as was presented in the Key Policy Insights. In Italy, social and economic disparities follow regional lines more closely than in other OECD countries (Figure 1.1). Regional disparities are especially marked for employment and income as well as safety, the environment and civic engagement. Regional disparities follow the historical north-south divide (Figure 1.2). Some regions in the South have among the lowest well-being outcomes across the OECD, while the best performing regions in the North are among the best performers in the OECD (Figure 1.3). Regional disparities are entrenched and in some dimensions, such as employment rates and relative poverty, they have widened over time (Figure 1.4).

Improving prospects for disadvantaged social groups and lagging regions would generate large gains in national income and well-being. High and persistent regional inequalities in economic, social and well-being dimensions coupled with the lack of prospects and opportunities in lagging regions weaken social cohesion, fostering resentment and creating political tensions. This chapter identifies reform priorities of Italy’s tax and benefit system and regional development policies to foster access to jobs in the formal economy, boost work incentives and reduce poverty.

Regional dispersion in well-being is markedly higher than in income alone, (Figure 1.5). Using subjective measures of well-being, individuals in the South report lower well-being than those with the same income living in the Centre and North (D’Alessio, 2017[1]). This gap between regional dispersion measures of income and of well-being is larger in Italy than in most other OECD countries for which data are available (Veneri and Murtin, 2016[2]). All this points to the strong role played by factors other than income in determining large regional disparities in the quality of life in Italy.

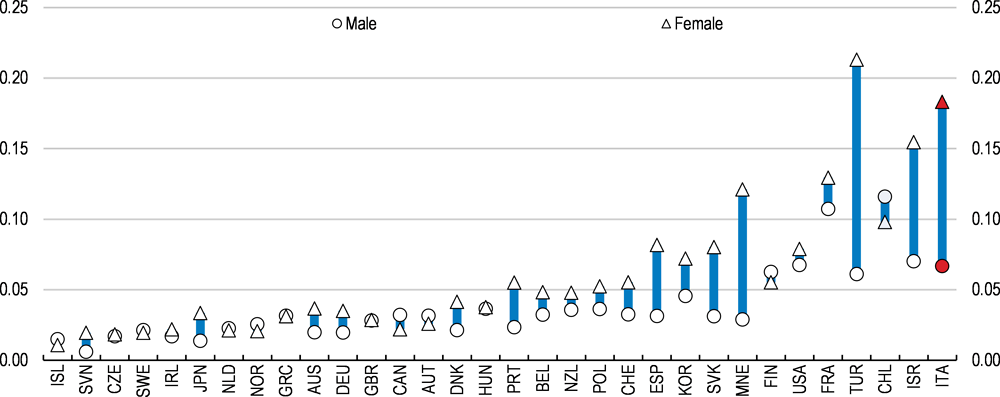

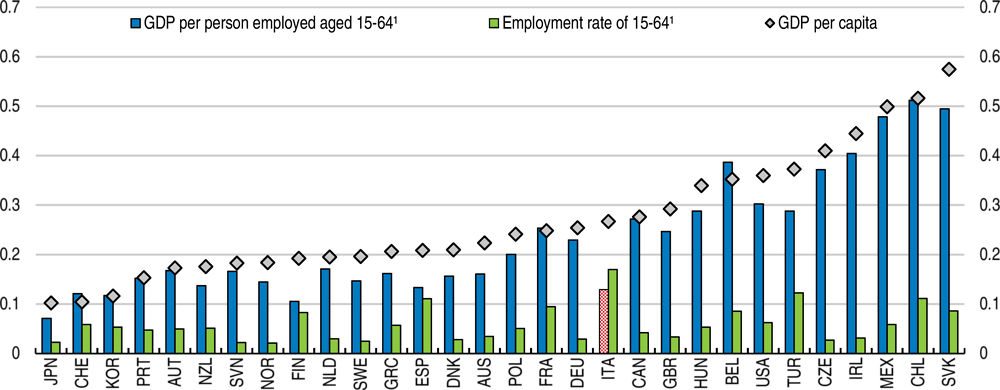

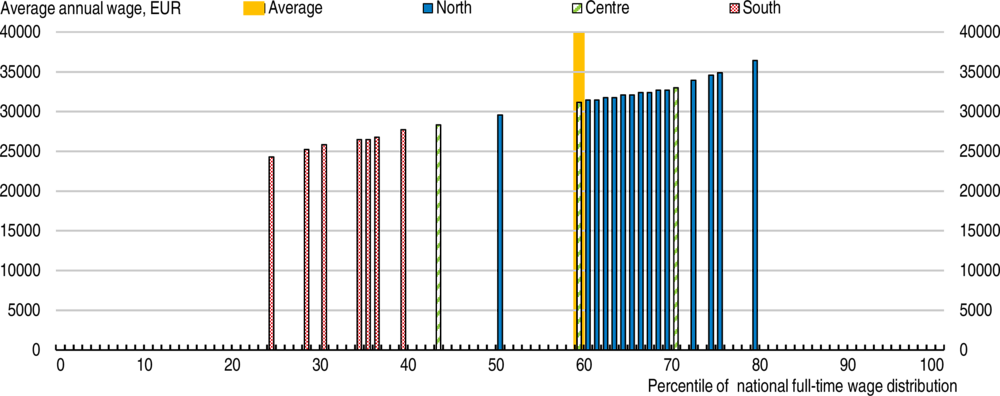

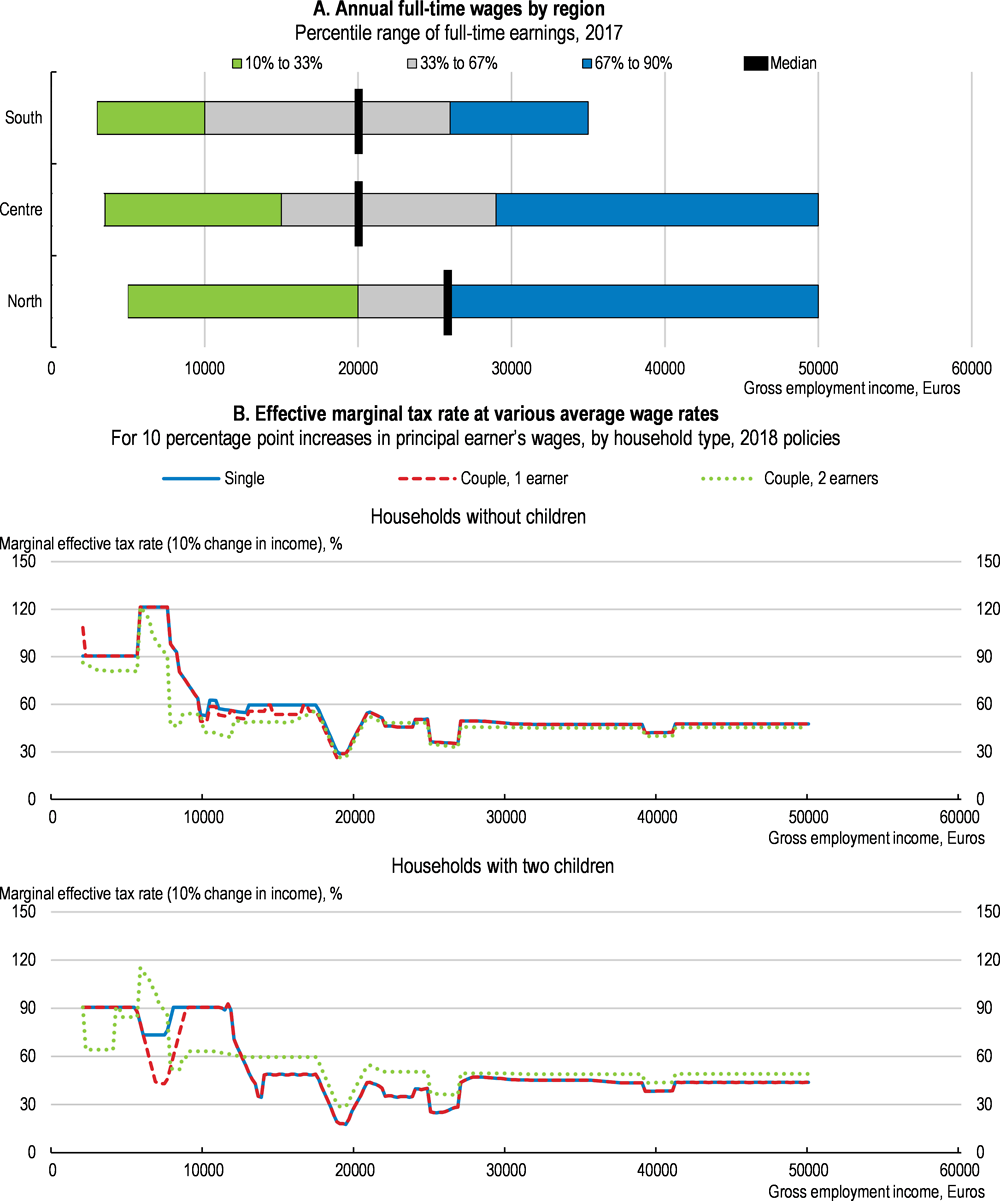

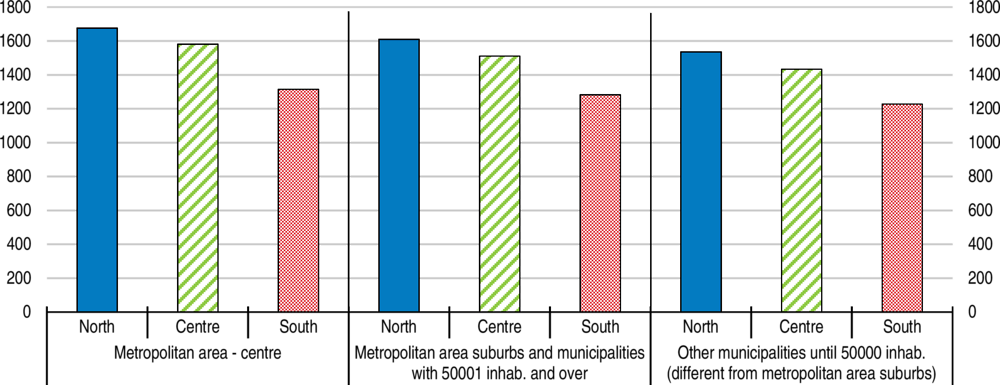

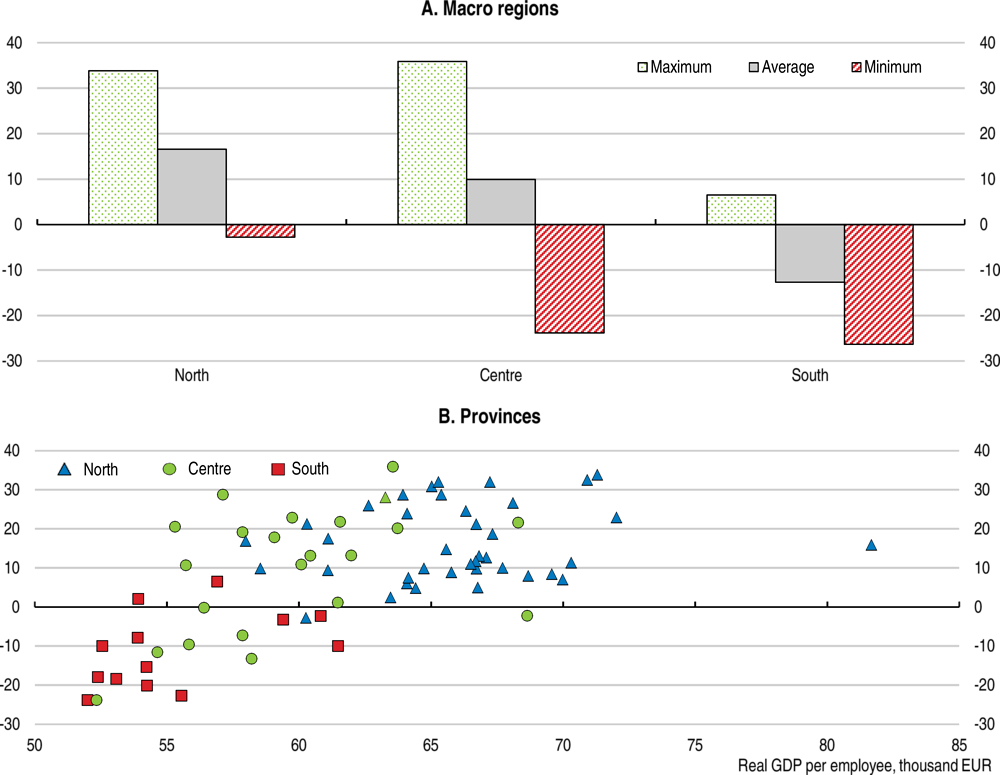

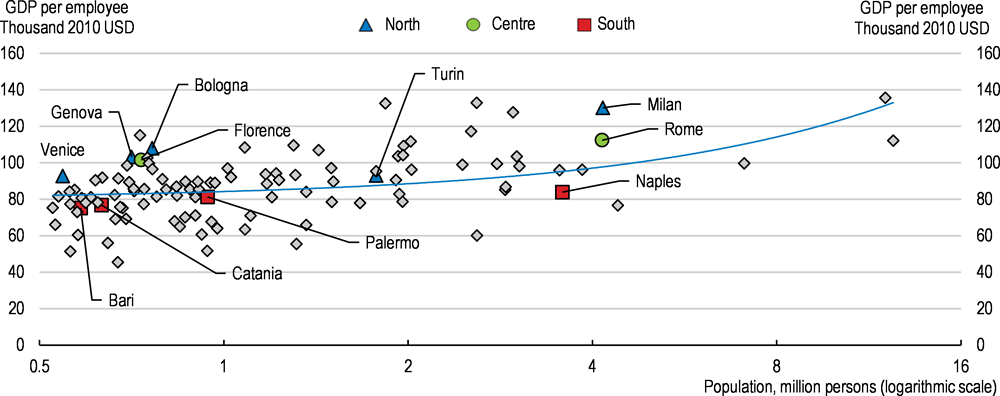

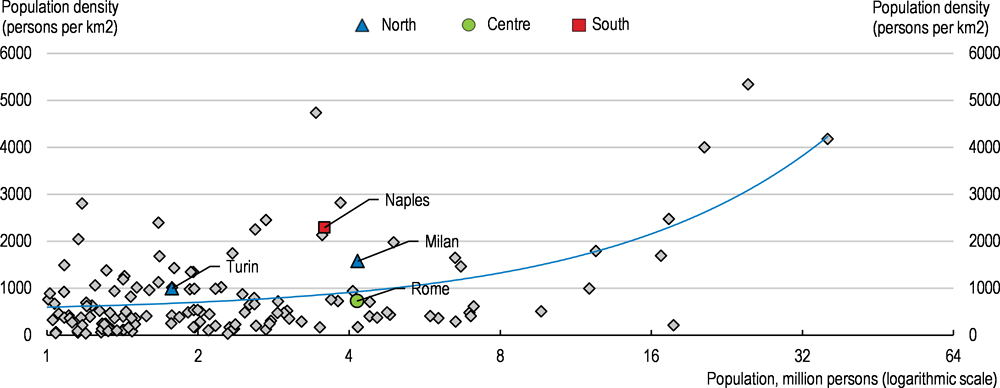

Regional differences in GDP per capita in Italy primarily reflect differences in employment rates, especially among women (Figure 1.6). This is unlike most OECD countries where productivity disparities play a much larger role in explaining differences between regions in GDP per capita (Figure 1.7). Moreover, wages in Italian lagging regions are lower than in more advanced ones. In southern regions, average wages are around 14% below the national average, while labour productivity is 20% lower, while in the North-west wages are 8% above the national average and labour productivity is 12% higher. The average wage in southern regions is around the 30-40th percentiles of the national full-time wage distribution while the average wage in most northern regions are near the 60-80th percentile (Figure 1.8).

Lower wages combined with low employment rates lead to lower household earnings in lagging regions. Though a large share of workers in lagging regions gain some income from informal work (Figure 1.9), such jobs are often associated with lower productivity and poorer working conditions and income.

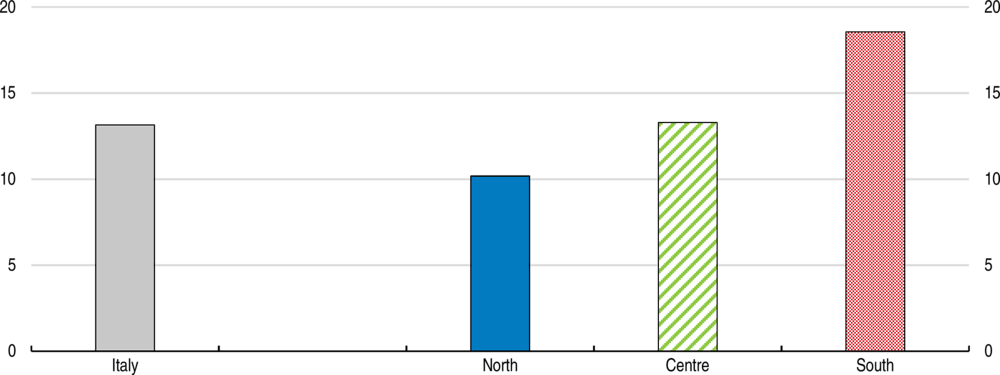

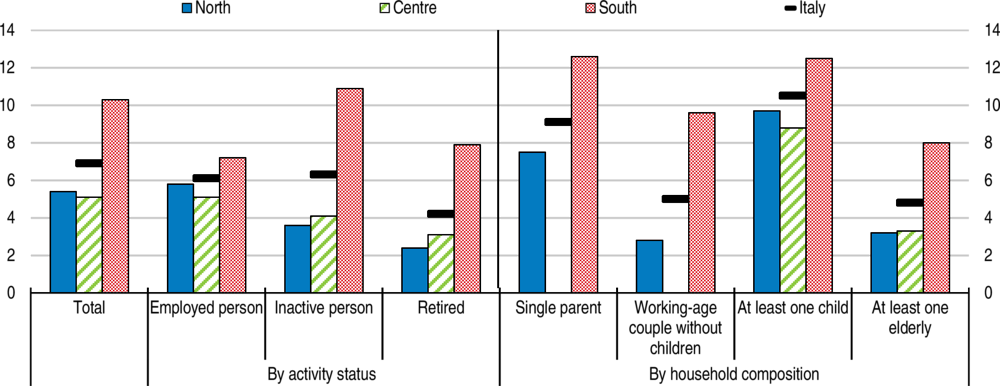

Poverty rates vary widely among Italy’s regions and across socio-demographic groups (Figure 1.10). Disparities in poverty follow the north-south divide as poverty rates – in both absolute and relative terms – are generally higher in southern than in central and northern regions across all household types. Southern regions have among the highest poverty rates across all regions in OECD countries at the NUTS-2 level, while some northern regions are well below the OECD average (Figure 1.3). Poverty is especially high for families with children and increases with the number of children, while it is lowest among retirees. Though poverty rates are highest among the unemployed, at about 25%, in-work poverty has also risen (Figure 1.11).

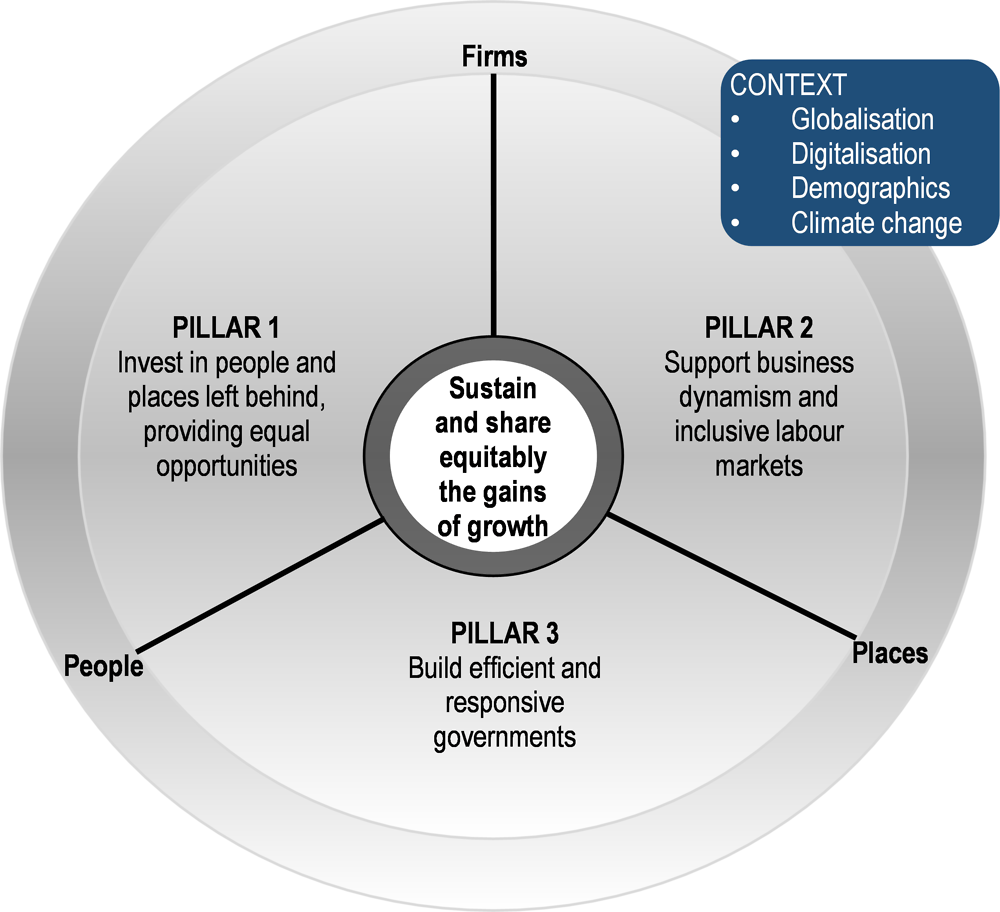

Reducing Italy’s social disparities requires addressing its large regional inequalities by improving welfare and supporting sustained growth. This chapter identifies reform priorities of Italy’s tax and benefit system and regional development policies to boost growth and share more equitably its gains by fostering inclusive access to good quality jobs in the formal economy, strengthening work incentives and reducing poverty. These ambitions and policy measures apply the OECD’s Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth (Box 1.1) (OECD, 2018[3]).

In 2018 the OECD Ministerial Council adopted a Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth, to guide policies to better achieve growth that benefits all and that allow for people, regions and business to fulfil their potential. The framework is not prescriptive, instead emphasising specific policy options that can adapt to Italy’s circumstances. It is centred on three broad principles (Figure 1.12):

-

1. Invest in people and places that have been left behind through (i) targeted quality childcare, early education and life-long acquisition of skills; (ii) effective access to quality healthcare, justice, housing, infrastructures; and (iii) optimal natural resource management for sustainable growth.

-

2. Support business dynamism and inclusive labour markets through (i) broad-based innovation and technology diffusion; (ii) strong competition and vibrant entrepreneurship; (iii) access to good quality jobs, especially for women and underrepresented groups; and (iv) enhanced resilience and adaptation to the future of work.

-

3. Build efficient and responsive governments through (i) aligned policy packages across the whole of government; (ii) integration of distributional aspects upfront in the design of policy; and (iii) assessing policies for their impact on inclusiveness and growth.

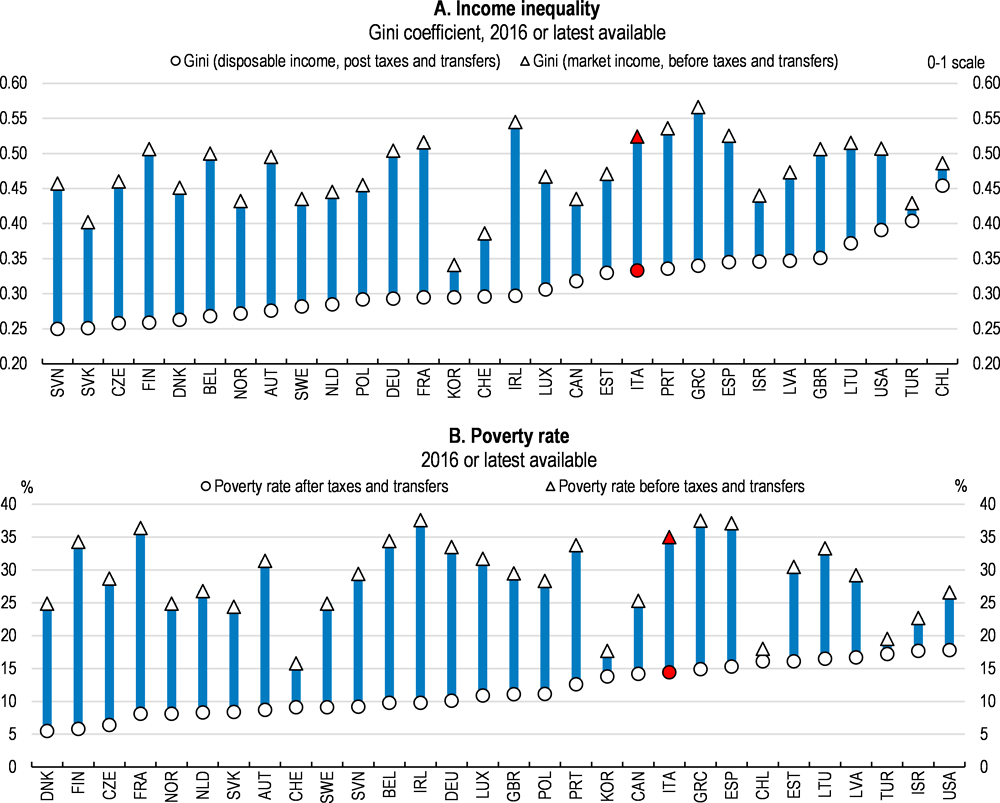

Italy’s tax and benefit system can do more to support employment and to lower poverty

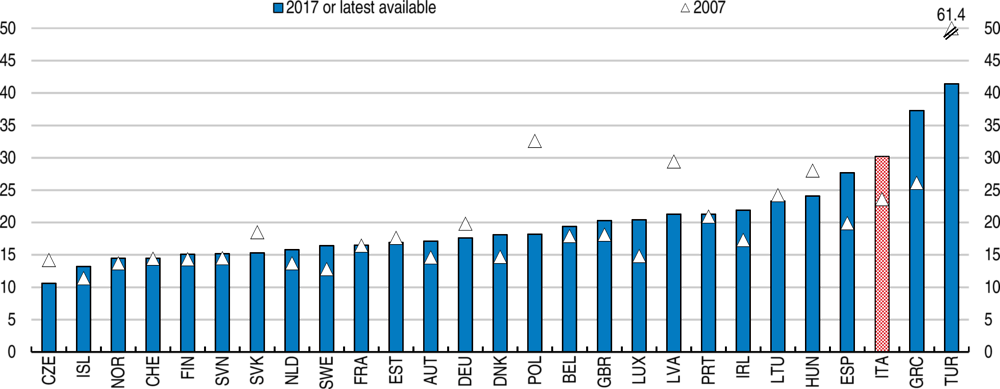

In Italy, inequality and poverty are above the OECD average (Figure 1.13). Italy’s indicators of disposable income inequality in Italy are below those of the United Kingdom but significantly higher than those of France or Germany. This reflects the large inequality in market income (the fourth highest among OECD countries), which the tax and benefit system only partly offsets. After taxes and transfers, Italy’s poverty rate remains among the top half of OECD countries. Italy’s high pension spending and limited social protection favours older people ahead of the young. As discussed below, well-designed reforms of the personal income tax and social benefit system would improve jobseekers’ ability to find work and better protect young and working age people from poverty.

Italy’s tax and benefit system discourages work

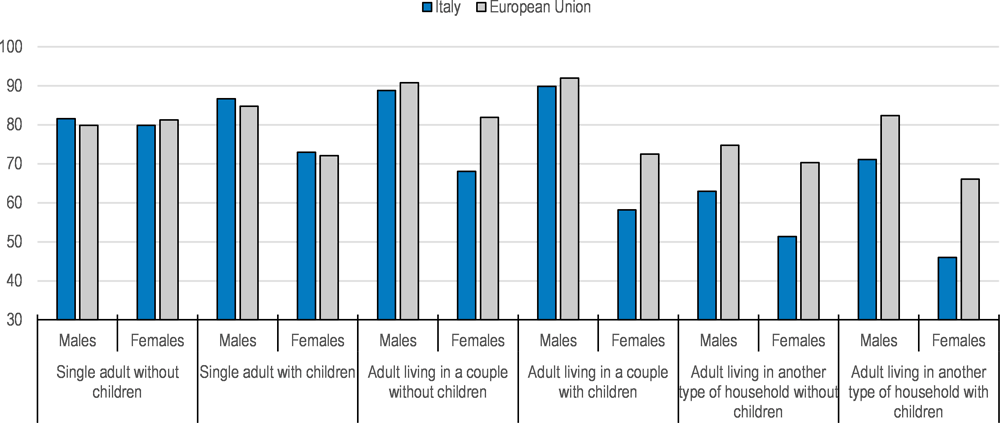

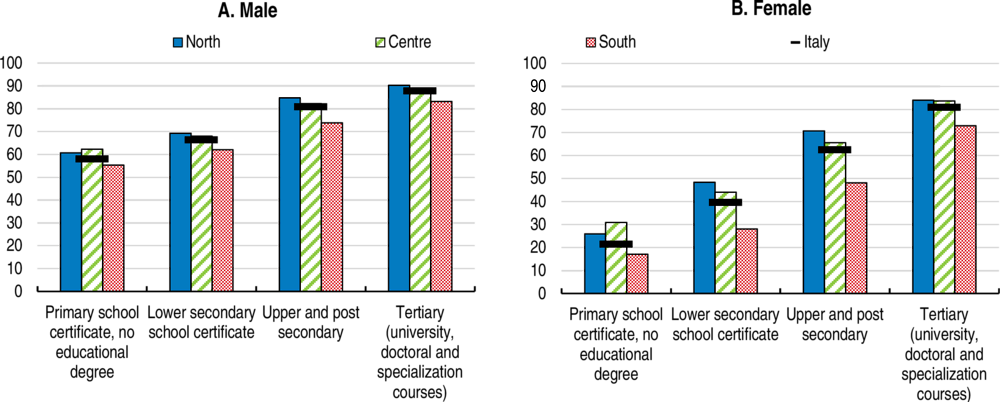

The size and structure of Italy’s tax and benefit system discourage employment, especially among low wage earners and second earners in couples. This is especially problematic in lagging regions where wages tend to be lower than in more developed ones. The shares of single men and women who work in Italy are similar to other European countries. However, among members of a couple, Italy’s employment rates fall below European averages, especially among women and in households with caring needs (Figure 1.14). Second earners’ decisions to seek employment tend to be more sensitive to work incentives and expected disposable income than primary earners (OECD, 2011[4]), especially in Italy (Bargain and Peichl, 2013[5]; Bargain, Orsini and Peichl, 2013[6]; Immervoll et al., 2011[7]). As the female spouse is usually the second earner in Italy, like in most OECD countries (Thomas and O’Reilly, 2016[8]), weak work incentives and low expected income discourage employment among women. Employment rates are markedly lower among women with less education and in regions with lower average wages (Figure 1.15).

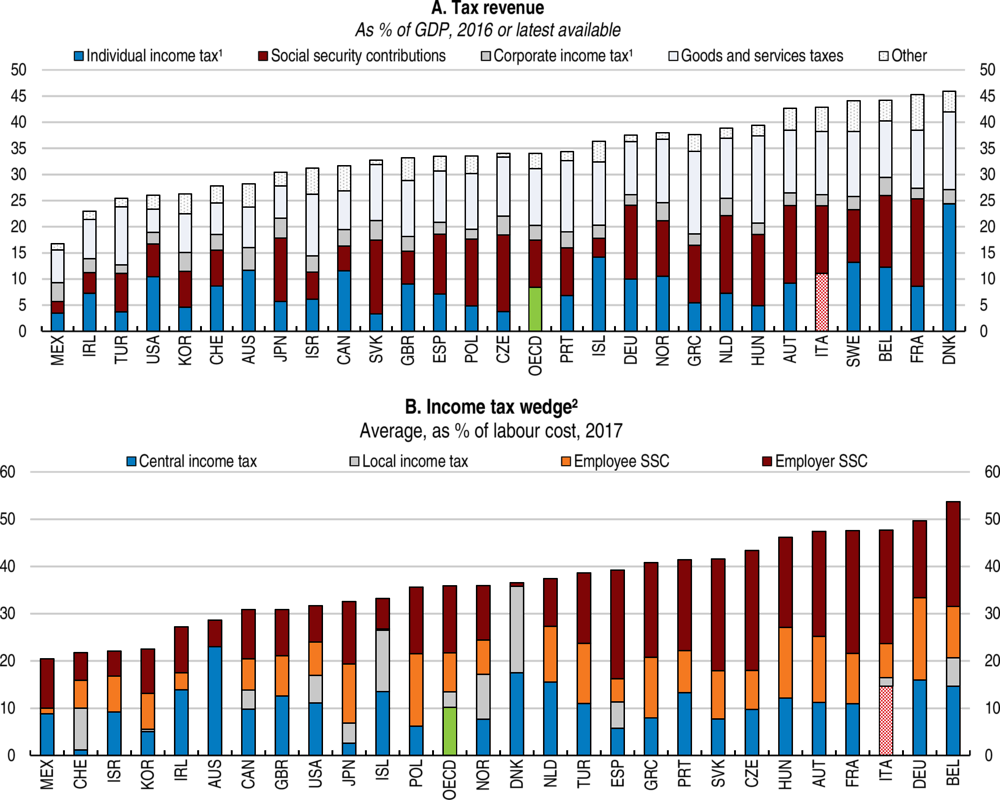

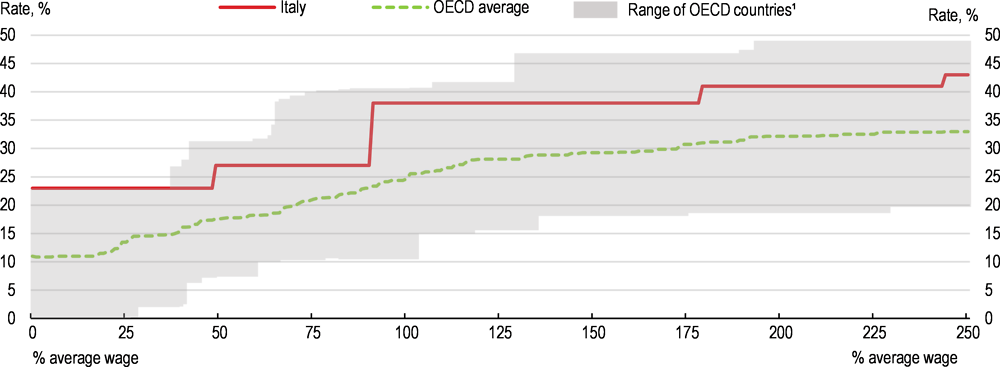

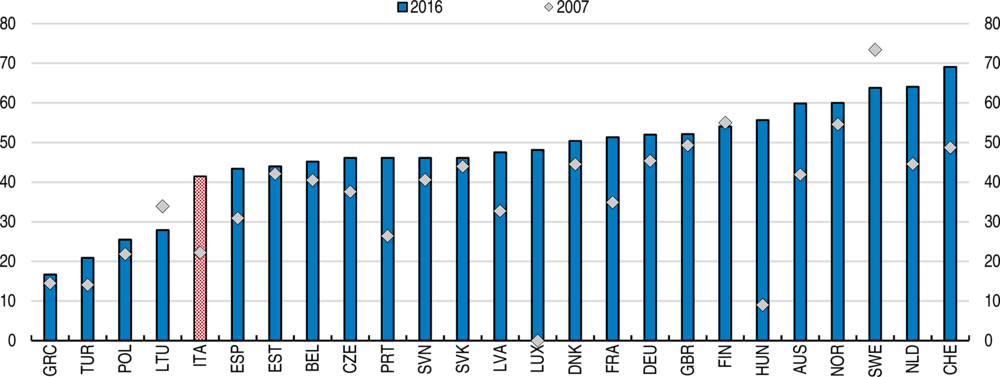

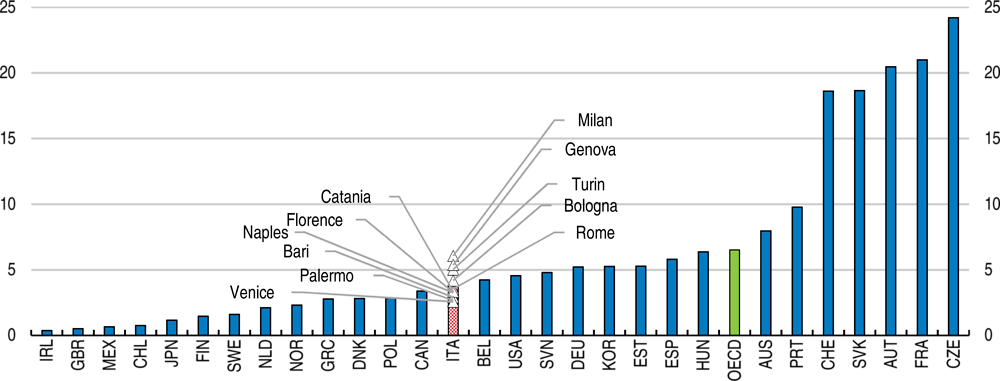

Italy’s tax share is among the highest relative to GDP across OECD countries (Figure 1.16, Panel A). Personal income taxes and social security contributions amounted to 24% of GDP in 2016. Corporate income and indirect taxes generate smaller shares of overall revenues than in most OECD countries, even if they too are large relative to GDP. High employer social security contributions and personal income taxes make Italy’s labour income tax wedge one of the widest of any OECD country (Figure 1.16, Panel B). This curbs labour demand especially in low productivity areas.

Temporary cuts in employer social security contributions over 2015-2018 for new permanent contracts and for targeted workers, such as the young, boosted job creation over this period (Table 1.1). The 2019 Budget introduces corporate income tax breaks for firms expanding employment. However, these tax breaks are likely to have a narrower effect in encouraging employment than a cut in social security contributions as only firms liable to pay corporate income tax will benefit from these tax breaks. Permanently reducing employer social security contribution rates, particularly for low income jobs, would better improve Italy’s competitiveness and boost job creation for a given reduction in revenues (Johansson, 2016[9]; De Mooij and Keen, 2012[10]).

Italy’s statutory personal income tax rates are also high (Figure 1.17). Taxpayers with very low incomes are liable to income tax, unlike many OECD countries where they benefit from a zero tax rate. Instead, in Italy low-income taxpayers and taxpayers supporting dependants benefit from tax credits, transfers and allowances. This system limits tax liabilities for very low income households without dependent children, largely through family tax benefits, and supports very low income households with dependent children through family benefits and transfers (Figure 1.18 and Table 1.2).

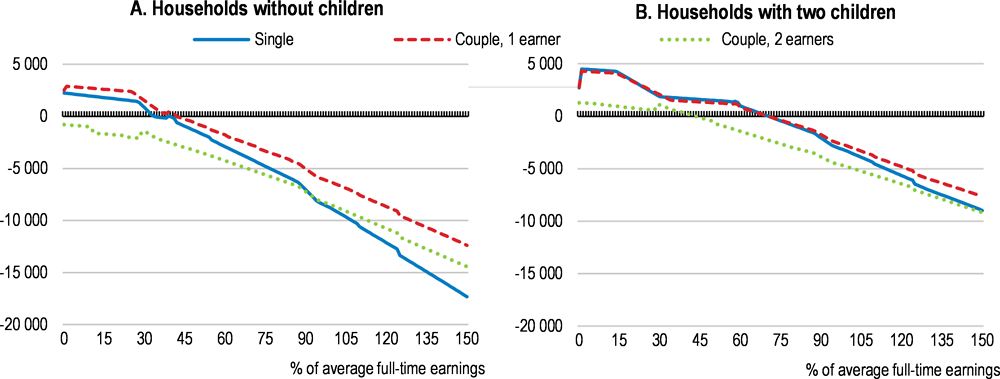

The various benefits, credits and transfers mean that in Italy an individual’s effective tax rate depends on their household’s composition and income. The current system penalises households with a second earner and poor households with children by excluding low income households from some tax credits, resulting in higher average effective tax rates (Figure 1.18). The difference in household tax burdens among household types is larger at lower incomes than at higher incomes. Other OECD countries, whether they assess tax liabilities against individual or household income, also adjust effective tax rates according to household composition. How these adjustments are made brings trade-offs between equity and efficiency. In general, the more dependent an individual’s effective tax liability is on other household members’ incomes, the greater the disincentive for the second earners to seek employment (Box 1.2).

In Italy, earners lose eligibility for many tax credits, allowances and transfers when their incomes are at relatively low levels, raising their effective marginal tax rate (Table 1.2). For example, the in-work benefit of EUR 80 per month phases in at moderate wage levels (higher than the wage rates of the working poor) and then phases out sharply as incomes rise from EUR 24 600 to EUR 26 600, raising the marginal effective tax rates markedly. In lagging regions, where more jobs are paid at lower wages, a larger share of households face these high effective marginal tax rates, which weakens work incentives (Figure 1.19). The tapering in the effective tax rate is not smooth, as households gain and then lose eligibility for specific transfers or benefits as their income rises through thresholds that differ between different tax credits and transfers (Figure 1.19, Panel B). This can create inconsistencies between otherwise similar households.

In 29 out of 36 OECD countries, personal income tax (PIT) is assessed against an individual’s income. Seven countries require and another four give taxpayers the option of assessing their PIT on a couple’s joint income, or even on the income of all members of the household. Some countries, including Italy, with personal income assessments in practice have a hybrid system, as they provide tax relief or allowances based on joint or household income or provide credits that can be transferred between spouses.

The choice of tax unit entails a trade-off between equity between families, equity between family structures (e.g., singles relative to couples), marriage neutrality (not providing an incentive or penalty when two individuals marry) and progressivity across income levels. No tax structure can simultaneously achieve all objectives.

Whether the individual or the couple is the tax unit affects the neutrality of the tax and benefit system between singles and couples, and the incentives for the second earner in a couple to enter work. When the couple or family is the tax unit, families earning similar total income pay similar levels of taxes, regardless of how earnings are distributed within the couple, improving horizontal equity across families. However assessing income jointly combined with progressive tax rates discourages second earners, as the second earner will face a marginal tax rate equal to that of the primary earner, which is likely to be higher than if the second earner was assessed independently. A larger difference between spouses’ incomes will amplify this disincentive.

Tax and benefit systems that assess income individually but provide tax credits, allowances and transfers on the basis of joint or household incomes, such as Italy, generate high marginal participation tax rates for the household as the second earner enters employment, especially in low-income families that benefit from these allowances.

Similar trade-offs apply to the design of working or earned income tax credits, such as in Italy’s system. These supplement incomes when employment pay is low. Eligibility thresholds that are based on total household income and circumstances can discourage second earners from entering low-income work, as the additional income may reduce the tax credit paid to the household. Eligibility criteria based solely on the individual’s income would avoid this disincentive, but may lead to individuals in high-income households benefiting from the transfer.

Family policies can offset the employment disincentives for second earners of family-based tax assessment systems. For example, in France, income tax is assessed jointly and then adjusted for the number of family members, lowering marginal rates as family size grows. To encourage spouses to enter employment, the French government provides capped allowances, tax credits and subsidies for childcare and household assistance. Social benefits, such as subsidised access to childcare or children’s meals, can further reduce work disincentives.

Sources: (Thomas and O’Reilly, 2016[8]; Colonna and Marcassa, 2015[12]; Luca, Rossetti and Vuri, 2014[13]; Alm, 2005[14])

The structure and withdrawal of family tax credits favours households with an inactive second earner, especially when the second earner can only access low wage work. A household with one earner receiving the average full-time salary is entitled to a tax credit of EUR 710 if the second earner’s annual income is below EUR 2 840. The household becomes ineligible for this credit once the second earner’s income rises above this level, leading to high effective tax rates for the household as the second earner enters work at low wages or part-time. This loss of the tax credit adds to other costs faced by the household as the second earner starts working, such as childcare (discussed below). This further discourages labour force participation of second earners especially in lagging regions where wages are lower. In contrast, in many other OECD tax systems the second earner faces a lower effective tax rate than the first earner at most wage rates.

The benefit system inadequately addresses poverty and social disparities among the young and the working age population

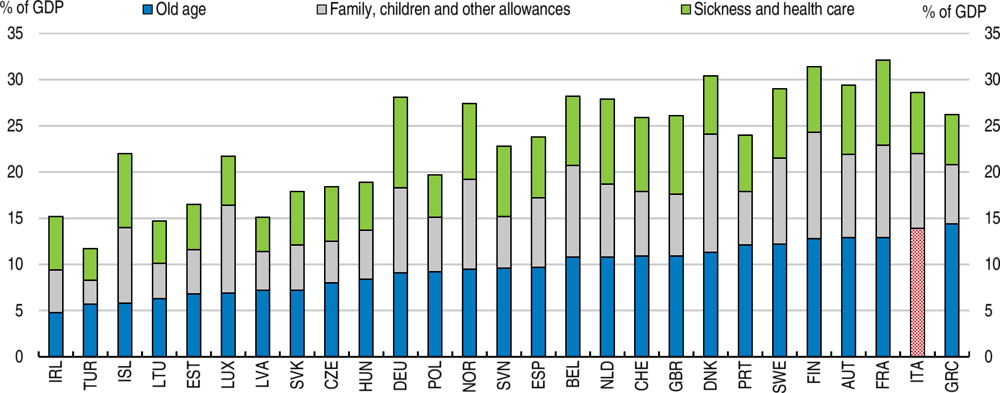

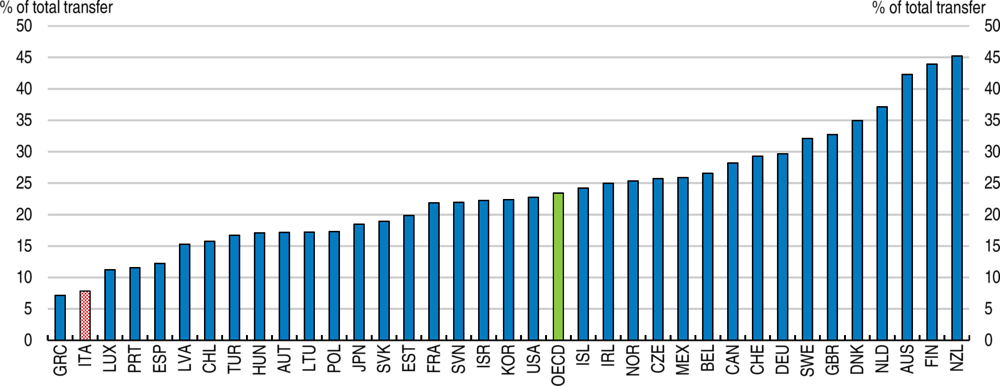

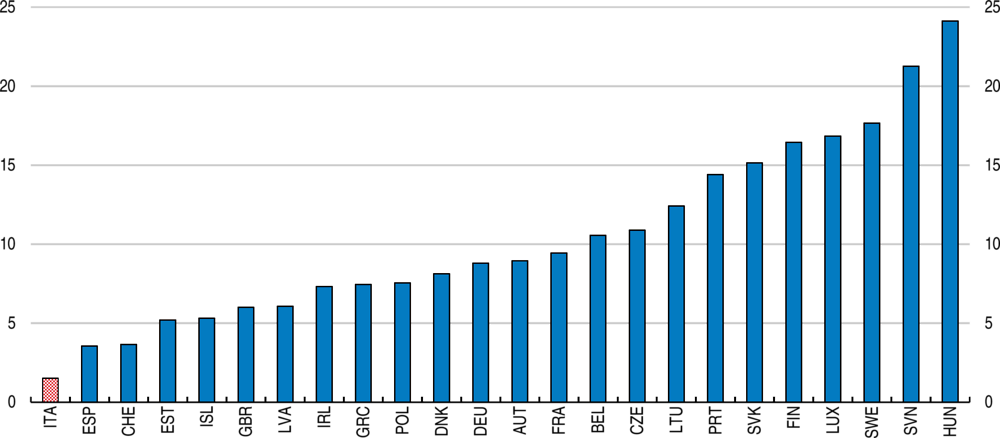

Pensions account for about half of total social protection spending, a higher share than in most OECD countries (Figure 1.20). As a result, spending as a share of GDP on family benefits, active labour market, disability and housing programmes is lower than elsewhere (Figure 1.20). Furthermore, social transfers to the working age population are poorly targeted as only a small share of them reach the poorer households (Figure 1.21).

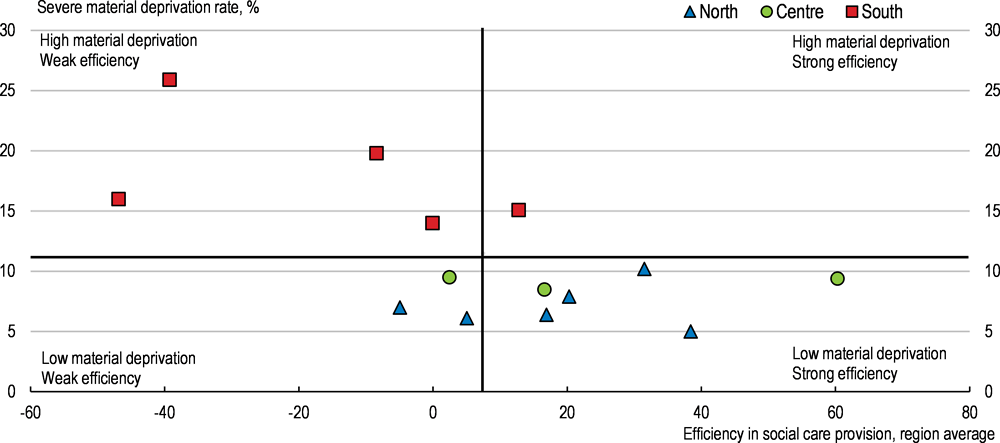

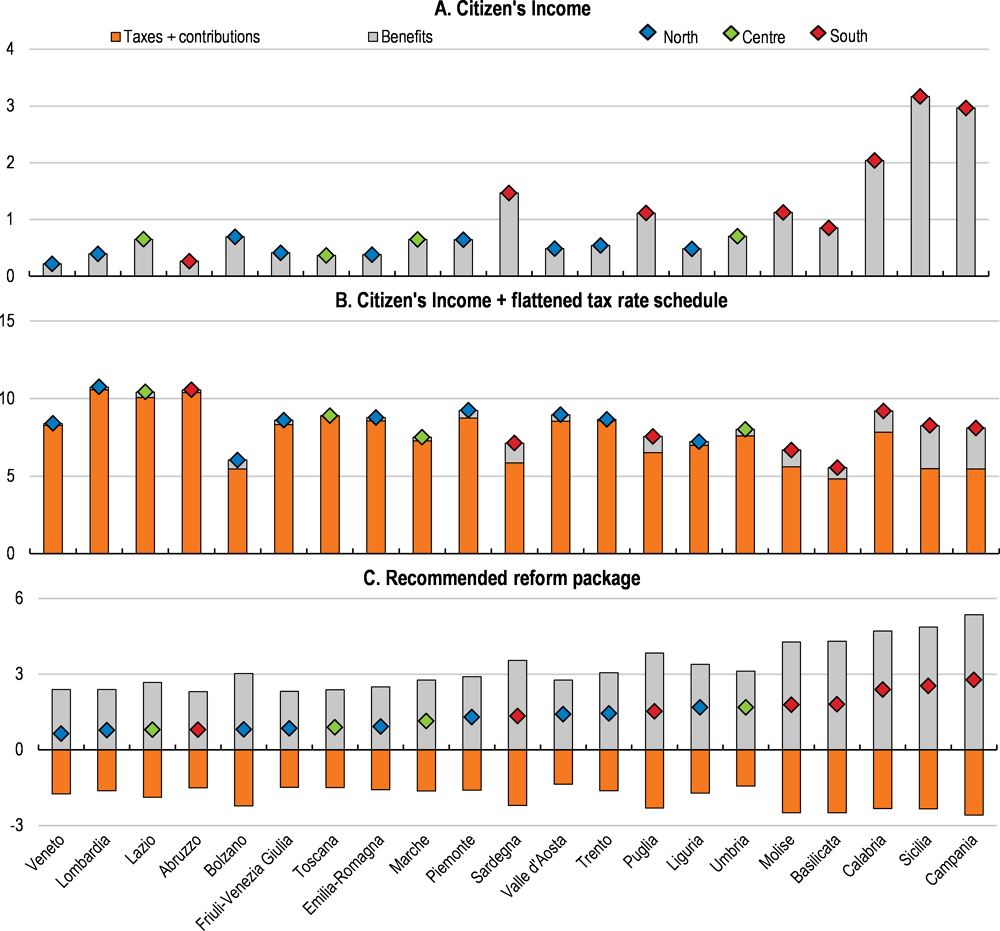

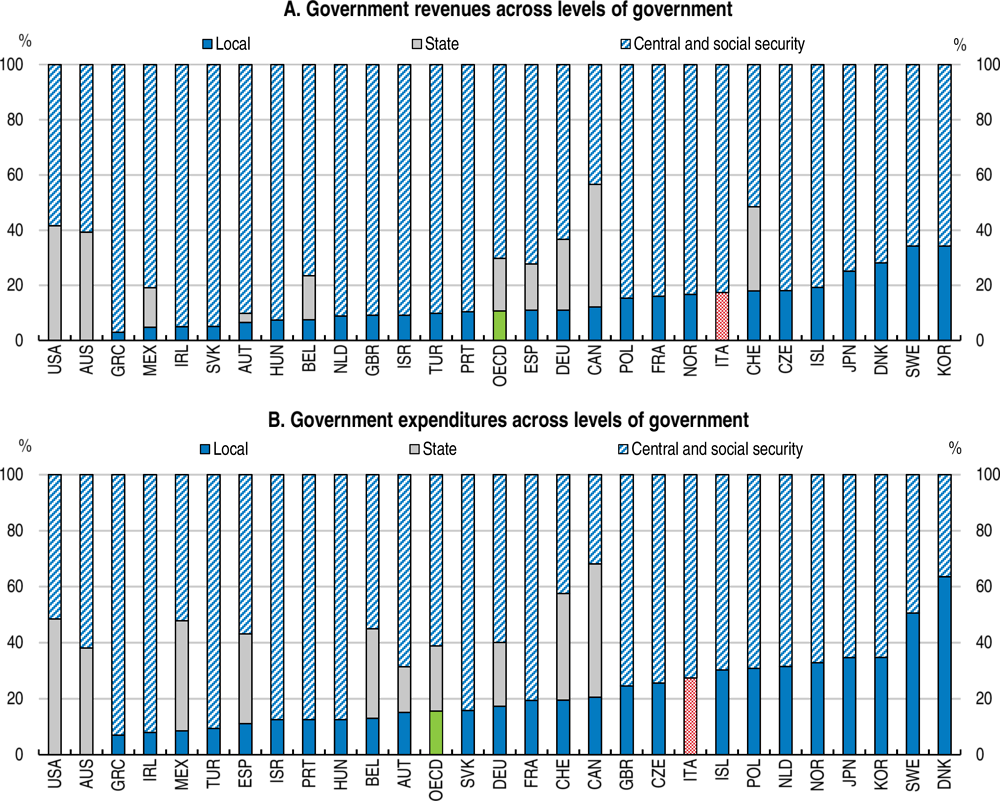

Social spending does little to reduce regional disparities. Municipal authorities are responsible for implementing social protection programmes but capacity and resources vary with the prosperity of the region (Figure 1.22). Lagging regions have larger populations with social needs, but fewer resources and less capacity to address these (Frazer and Marlier, 2009[15]).

Italy’s pension spending is high and new policies will raise it further

Italy’s pension spending is the highest across OECD countries and absorbs more than half of Italy’s total social spending (Figure 1.20). Reforms since the mid-1990s have helped to contain rising pension spending, slowing it to below nominal GDP growth. The 2012 Fornero reform extended contribution periods by increasing the retirement age of women to that of men, accelerated the transition to a notional defined contributions system, delayed when a worker would be eligible for pensions and strengthened the link of retirement age to life expectancy. Following this reform, older workers extended their working lives, although they are still shorter on average than in most OECD countries. According to the European Commission, without considering the effect of the retirement policy changes introduced with the 2019 budget, pension spending will rise by 2040, because of the fast ageing process, to the highest level of any European country at any point in the European Commission’s 50-year projection framework, before falling to below 2016 levels by 2060 (European Commission, 2018[16]).

The changes to retirement rules provided in the 2019 budget will lower the effective retirement age. Workers who are aged at least 62 and with at least 38 years of contributions will be allowed to retire with a reduced pension. The changes also weaken the link between life expectancy and retirement age by discontinuing until to 2026 the link between the updates of early retirement contribution requirements and developments in life expectancy. The 2019 reforms also expand access to early retirement for women. These changes reforms follow 2016 reforms that allowed workers to retire earlier by borrowing against future pension benefits (Iudicone, 2017[17]; Ministry of Economy and Finance, 2017[18]).

The 2019 changes to retirement rules are expected to result in up to 300 000 additional retirees in 2019, 330 000 in 2020 and 355 000 in 2021. Pension spending will rise by up to EUR 4 billion (about 0.2% of GDP in 2019) and by about EUR 8 billion yearly in 2020 and 2021, depending on how many eligible workers take-up the scheme. A worker accessing early retirement may lose between 2% and 16% of their standard pension.

Closing the early retirement scheme that the 2019 Budget introduced and reallocating the financial resources to growth-enhancing and social inclusion policies, such as the in-work benefit scheme discussed below, innovation policies and education would preserve the sustainability of the pension system and lead to a faster debt reduction. The sustainability of the pension system crucially also depends on raising the employment rate towards the EU average, and on stronger productivity growth. A sustained increase of 0.4 percentage points in total factor productivity growth would reduce pension spending by 1.1% of GDP from 2050.

Reforming tax and benefit policies to better fight poverty, encourage employment and improve inclusiveness

Over the past few years, introducing a guaranteed minimum income has become a priority of Italian governments (Sacchi, 2018[19]), in line with past OECD Surveys’ recommendations (OECD, 2013[20]; OECD, 2015[21]; OECD, 2017[22]). Guaranteed minimum income schemes act as last-resort safety nets for very low-income and-low wealth households. Design choices for guaranteed minimum income schemes centre eligibility thresholds and transfer amounts as well as the associated requirements of engaging in job-search, training, and other social programmes. As benefits are generally low and well below national poverty lines, such schemes by themselves reduce the depth of poverty, rather than lifting households out of poverty. That eligibility to guaranteed minimum income schemes is conditional on actively seeking work or joining training programmes and that benefits are often limited in time distinguishes guaranteed minimum income from universal basic income schemes, which are universal and unconditional (Box 1.3).

Sustained employment is the best antidote to poverty (Causa, Hermansen and Ruiz, 2016[23]). While the income transfers provided by guaranteed minimum income schemes can be effective in the short term in alleviating poverty, there is a trade-off between the transfer generosity and the incentive for beneficiaries to find work. To help beneficiaries move into employment, many guaranteed minimum income schemes require beneficiaries to actively seek work or take part in training or other social support programmes. To ensure that work pays for beneficiaries, some schemes reduce transfer amounts gradually as beneficiaries start gaining employment income, and a growing number of OECD countries provide in-work benefits to top-up the incomes of low-wage earners.

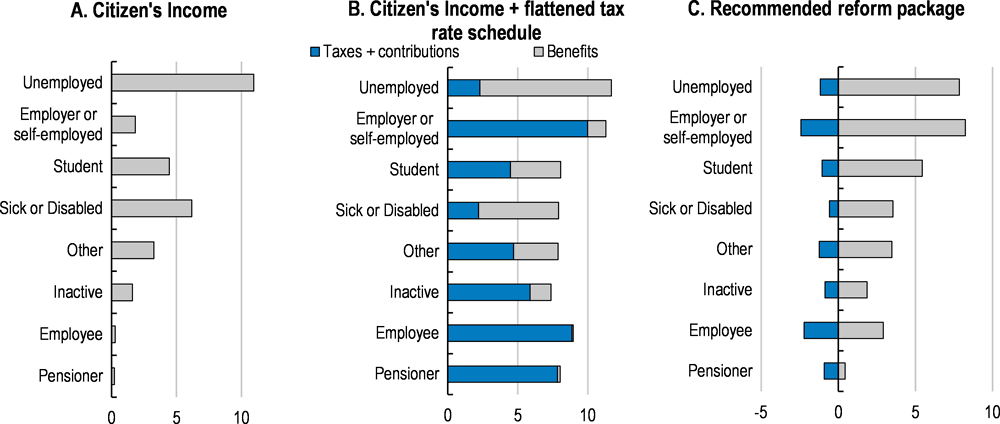

This section assesses three scenarios based on planned and hypothetical tax and benefit policy reforms in Italy to reduce poverty and expand employment. The reform options are compared with Italy’s tax and benefit policies at the end of 2018, following the July 2018 expansion of the Inclusive Income Scheme (REI). The reform scenarios are:

-

1. Citizen’s Income scenario. The Citizen’s Income (Reddito di Cittadinanza) will be introduced from April 2019 and will replace the REI. Its transfers and eligibility thresholds will be more generous than those of the REI. Overall, the Citizen’s Income could lower poverty rates and the poverty gap substantially. Beneficiaries will only retain a small share of any gains in employment income, and only for the length of an existing Citizen’s Income agreement. This, interacting with other aspects of the tax and benefit system, risks discouraging recipients from obtaining full-time employment in the formal sector. Job search and other obligations of Citizen’s Income beneficiaries are intended to offset these disincentives but will need improved capacity.

-

2. Citizen’s Income and hypothetical flattened personal income tax rates scenario. Flatter personal income tax rates and reduced steps have been discussed for some time in Italy and have been considered by the current government. The effects of a flatter income tax rate schedule in conjunction with the Citizen’s Income warrant assessing, as these measures are likely to be highly costly. Without changes in deductions and allowances to maintain the progressivity of personal income tax, flatter income tax schedules will largely benefit high income households without improving work incentives for low-income households.

-

3. Recommended reform package. This would consist of a guaranteed minimum income, together with in-work benefits for low-wage earners, and a simpler system of personal income tax rates and credits. This system may better protect households from poverty and encourage formal sector employment, especially among second earners, at a moderate net cost for public finances. This policy mix draws on many countries’ approaches to addressing the same objectives.

Reforming Italy’s tax and benefit policies will affect households’ incomes and work incentives in addition to social and regional disparities, and public finances. The policy scenarios are modelled using the OECD’s Tax-Benefit model (Bulman et al., 2019, forthcoming[94]; Browne et al., 2019, forthcoming[95]). Simulations of the direct household-level effects are aggregated to regional and national level with the EUROMOD model. EUROMOD incorporates the population’s characteristics (Sutherland and Figari, 2013[26]) and enables to estimate the direct effect of the reform scenarios on tax revenues and benefit spending. All EUROMOD simulations take into account only the immediate effect of policy reforms given households’ existing compositions and characteristics, and do not allow for behavioural responses. In the longer-term, policy reforms may lead to behavioural changes, for example as reduced effective tax rates lead individuals to start working, which can effect employment rates, income and spending.

Universal basic income (UBI) schemes provide a uniform benefit to all, regardless of individual earnings, labour-market status or family or other circumstances. In contrast, guaranteed minimum income (GMI) benefits are conditional on recipients’ income and assets being below a certain limit and recipients are typically required to engage in job search and training programmes.

By being universal and unconditional, UBI recipients do not lose benefits as they gain income, limiting effective tax rates at low incomes as they start working. However being universal means that the UBI transfers are not targeted to those in greater need. This means that UBI schemes require much greater resources than GMIs to ensure that poor households can access a minimum income. Raising these funds requires much higher tax rates or very substantial cuts to existing social benefits (Browne and Immervoll, 2017[27]).

UBI proposals generally envisage transforming existing social payments and tax credits into a flat payment to all adults. The size of benefits is debated. Simulations find that transforming the existing GMI provided in most countries into a UBI, while ending existing social protection programmes would require large increases in tax revenues, and may lead in many countries to higher poverty rates as targeted benefits are converted to a universal income available to all.

UBIs have gained greater attention in recent years. Many see them as the right response to changing forms of employment that break down traditional, long-term employer-employee relationships, to fears of automation causing large-scale job losses, and to greater recognition of gaps in existing social protection systems’ coverage. UBIs have the attractions of being simpler than traditional tax and benefit systems and of avoiding high effective marginal tax rates as means-tested benefits are withdrawn as income rises.

The Netherlands and Finland have trialled UBI-like programmes, although they have been limited to particular groups – generally the unemployed – or regions – smaller towns (Pareliussen, Hwang and Viitamäki, 2018[28]). Livorno, in central Italy started a small 6-month trial in June 2016, providing 200 of the poorest households with EUR 500 per month, conditional on completing community service and showing that they are actively searching for work.

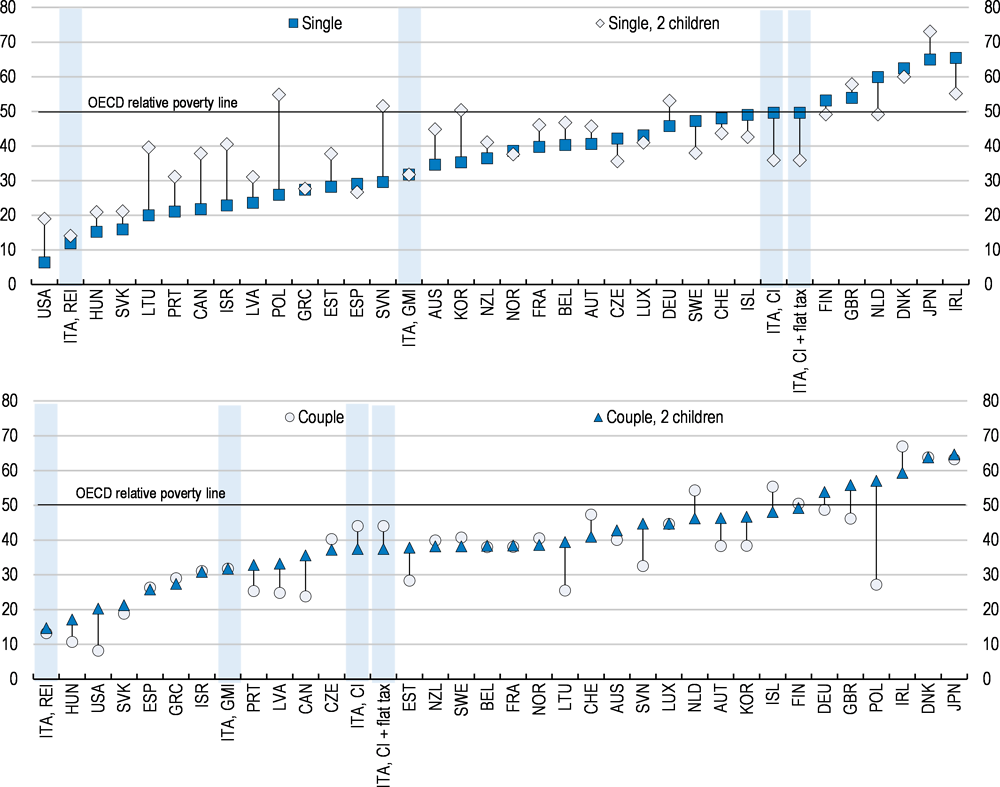

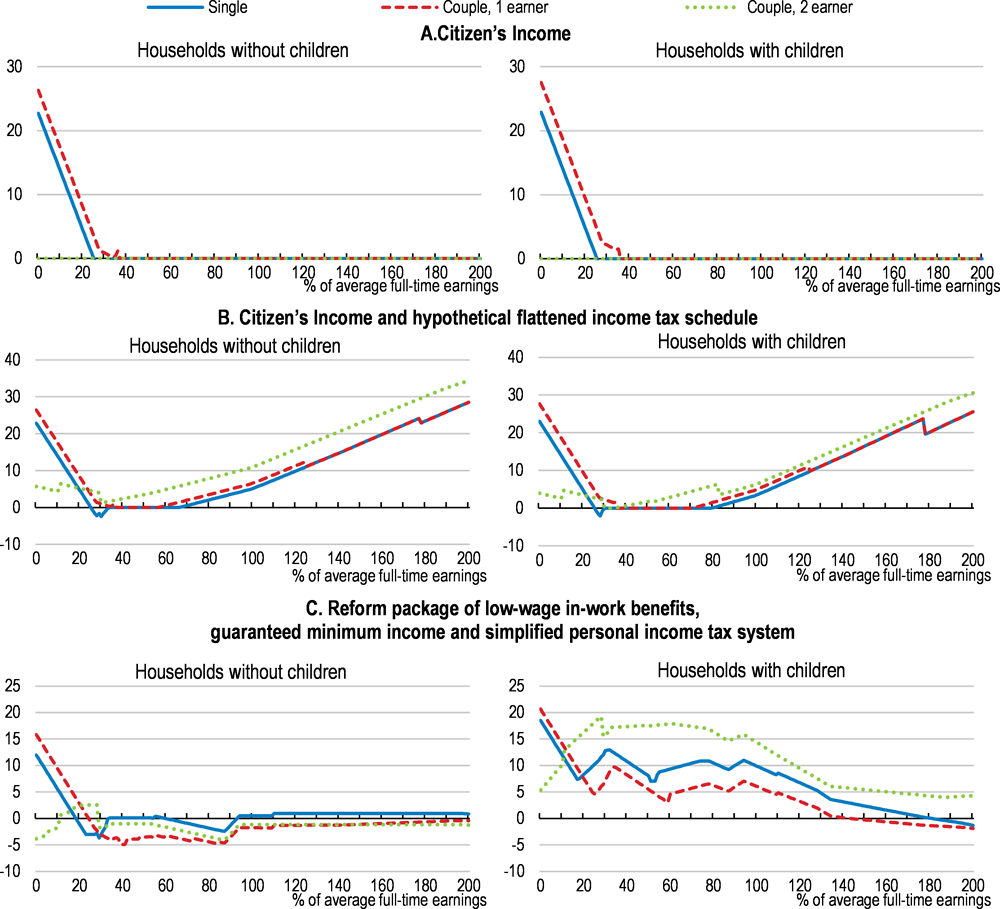

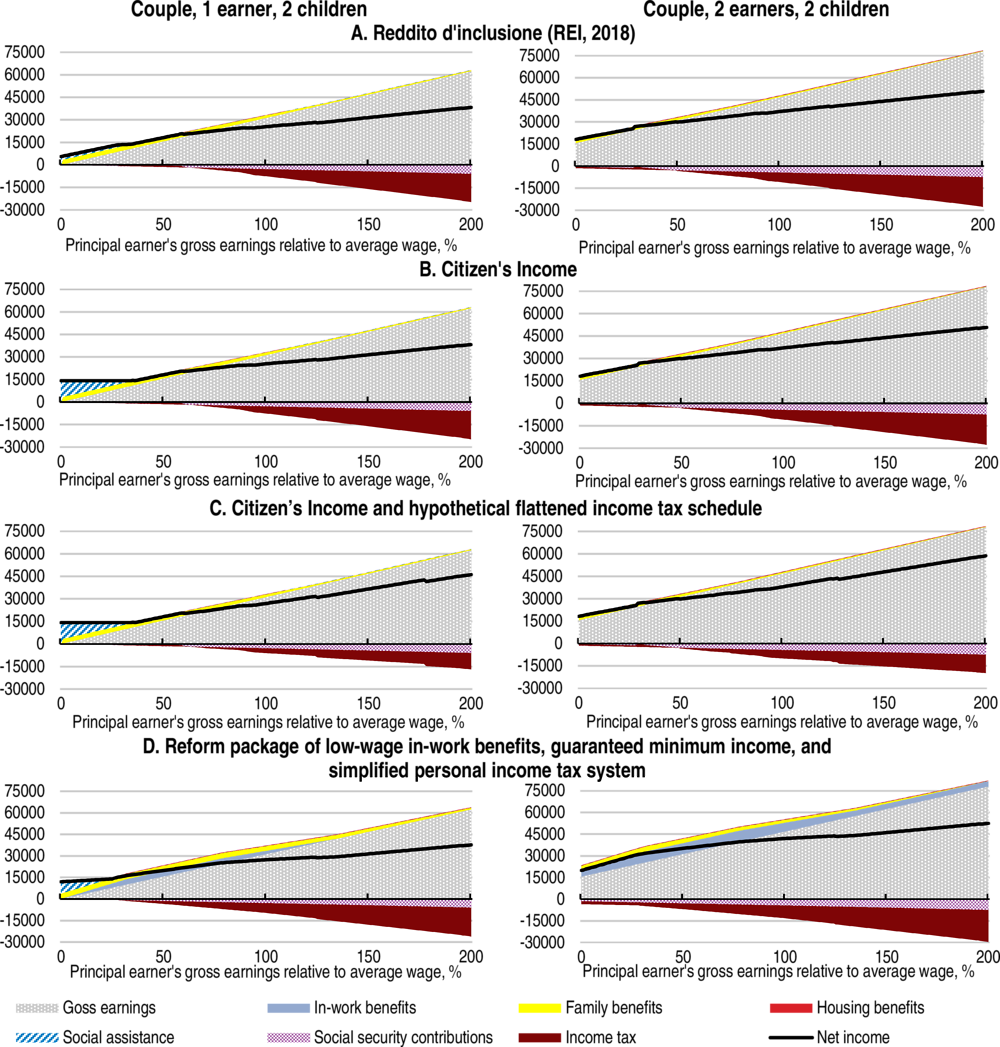

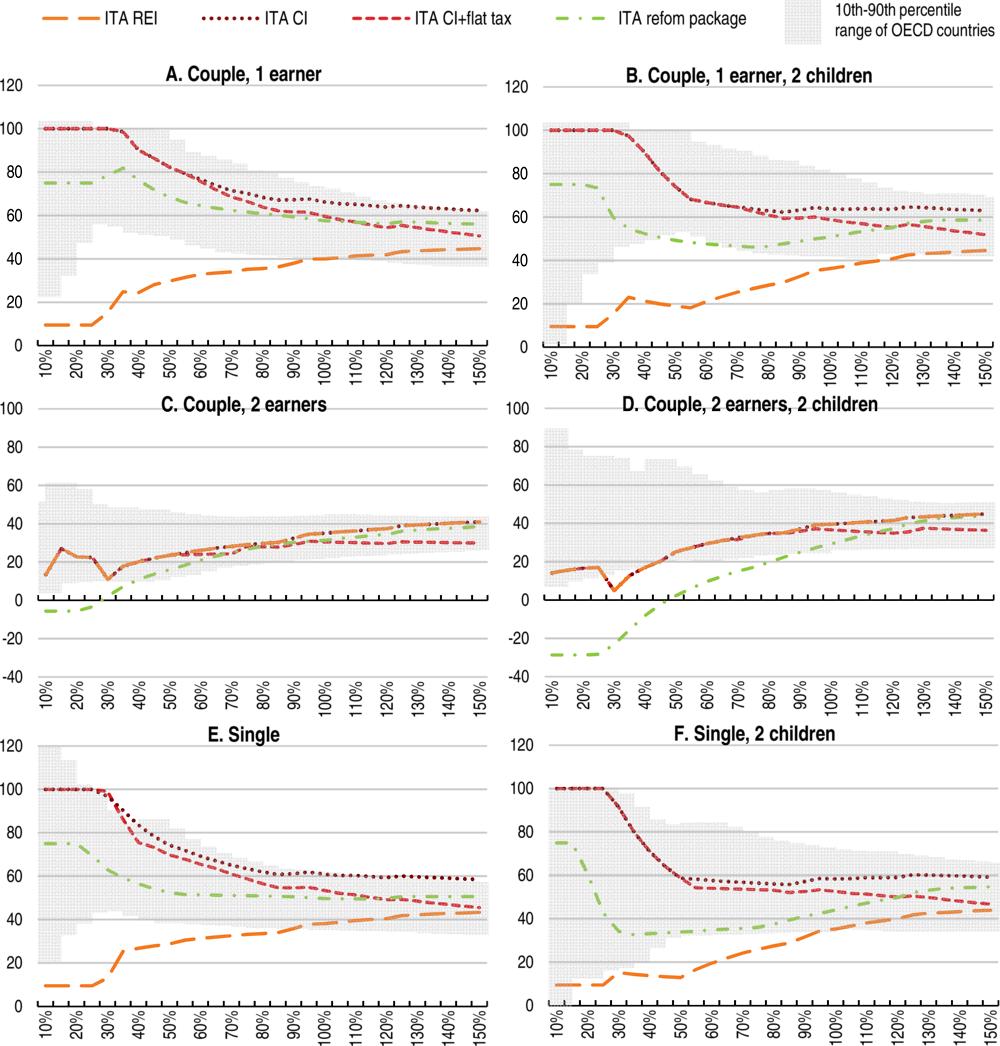

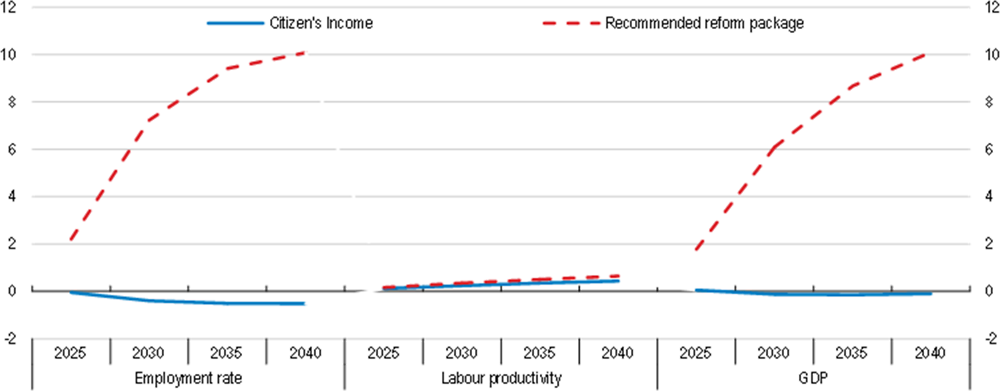

The effects of the three policy scenarios are presented across several Figures and Tables. Table 1.6 reports the effect of the policy scenarios on poverty rates, poverty depth (i.e., the gap between their incomes and the poverty line), inequality, tax rates at various income levels, and the net effect on public finances. Figure 1.23 illustrates the income out-of-work households would receive, relative to the national average full-time wage and compared with other OECD countries, under the 2018 Inclusive Income Scheme (REI), the Citizen’s Income and the recommended reform package’s guaranteed minimum income scheme. Figure 1.25 shows the change in income across the various policy scenarios relative to the 2018 REI for different household types across wage levels. Figure 1.26 illustrates the effects of the various policy scenarios on net earnings, and its components, for families with 2 dependent children and with either one or both adults working at different wage levels. Figure 1.27 shows the participation tax rates of the various policy scenarios of moving into work at different wage levels and household situations, compared with other OECD countries. Figure 1.31 shows the long-run macroeconomic effects of the recommended reform package on labour productivity and activity. Bulman, et al, (2019, forthcoming) provide additional results across a wider range of household types.

The REI introduced a national guaranteed minimum income to Italy

The Inclusive Income Scheme (Reddito di Inclusione, REI) was first introduced in early 2018 and was Italy’s first nationwide guaranteed minimum income scheme. Previously, some Italian municipalities provided local guaranteed minimum income programmes, and the REI had absorbed them. Eligibility to the REI was determined by the household’s income, assets and compositions, as measured by the Equivalent Economic Situation Indicator (ISEE). The ISEE is a synthetic measure of a household’s income and assets adjusted for the household’s composition and whether household members need special care (Box 1.4). As the REI was operating at the end of 2018, it is included in the baseline against which the Citizen’s Income and two hypothetical tax and benefit reform scenarios detailed below are compared.

The REI’s transfers and eligibility thresholds were low relative to other countries (Figure 1.23; Table 1.3). The REI’s cash transfers topped up eligible recipients’ very low incomes. This reduced the depth of poverty they faced – i.e., the gap between their incomes and the poverty line – without raising their incomes above the poverty line (Figure 1.23), similarly to most countries’ guaranteed minimum income programmes. Reflecting its low benefits and strict eligibility thresholds, the budgeted cost of the REI was small, at 0.1% of GDP.

The REI’s low eligibility thresholds and transfers mean it had minimal negative effect on employment incentives. Participation tax rate for beneficiaries moving into low-wage work were among the lowest across the OECD. In addition, REI beneficiaries were required to engage in job-search, training or other social programmes tailored to recipients’ needs.

Italy’s main instrument to means-test eligibility for social benefits is the Equivalent Economic Situation Indicator (ISEE – Indicatore della Situazione economica Equivalente). Households apply to the national social security institute (INPS) for an ISEE value. INPS calculates the ISEE value from information provided by the household and tax authorities. The household’s ISEE value determines whether its members can access non-contributory social benefits, ranging from the REI to subsidised childcare places.

The ISEE calculation is standard across Italy, while eligibility thresholds based on ISEE for specific benefits can vary between regions. Nationally, 23.4% of the population had an ISEE value at the end of 2016, with higher shares in southern than in northern regions, ranging from one-third of the population in Sardinia to 9.8% in Trentino. Requests for ISEE values peaked in 2010 and 2011 during the economic downturn.

The ISEE value for a household is calculated from the household’s income (Income Situation Index, ISR) and assets (Asset Situation Index, ASP), adjusted for the number and characteristics of household members:

ISEE = (ISR + 20% ASP)/(Equivalence scale)

The ISR covers all income sources from all household members, allowing for specific deductions, over the previous 12 months. These deductions include 20% of income from employment or similar sources, including unemployment insurance benefits, up to EUR 3 000, or, alternatively, 20% of the income from non-taxable benefits or pensions up to EUR 1 000. A family’s rental costs can be deducted up to EUR 7 000 per annum and by EUR 500 more for the third and additional children. Income and health expense allowances for each disabled household member can be deducted. These deductions lead to around 10% of households’ ISEE value to be zero in 2016.

The Asset Situation Index sums household wealth, including both movable and immovable properties, subtracting deductions and allowances. These rules favour renters over homeowners, as rent expenses are deductible from income, while home ownership increases the ISEE value.

Household sizes are adjusted to equivalent sizes by scaling the number of members to the power of 0.65, for up to 6 members. From 2019, households with more than two children can make additional deductions from their income and asset values.

A household’s initial ISEE value is calculated from the previous year’s taxable income and assets. An asset-poor household may only be eligible for social protection the year after losing their income. Conversely, the household will remain eligible for ISEE-assessed benefits even as they restart work. Reforms introduced in 2019 allow a household which already holds a current ISEE to request that it be recalculated based on their previous two months’ situation if a household member’s work situation changes and the household’s total ISR falls by at least 25%.

The ISEE has been criticised for how it weighs incomes and assets, and for applying the same equivalence scale to different types of benefits. However, individual benefits may apply specific eligibility thresholds. In practice, regions and local communities may adjust the criteria by applying discretion in valuing and calculating the components.

Sources: Motta (2011[29]); Ghetti (2012[30]).

The Citizen’s Income raises support for low incomes but risks weakening incentives to work

The Citizen’s Income scheme will replace the REI from April 2019. Table 1.3 summarises this scheme. It will provide a transfer to top-up poor households’ income to a minimum level. The income transfer is higher for larger households, although the scaling factor is capped, penalising large households. The Citizen’s Income will also provide transfers to cover rental or mortgage expenses, though this rental or mortgage allowance does not vary with the household’s size. The Citizen’s Income applies to households with working-age members, while a new “Citizen’s Pension” provides a safety net for very low income households made up of only people aged 67 or above. Households will be eligible for the Citizen’s Income if they have been resident in Italy for at least 10 years and continuously for the previous 2 years. The benefit is conditional on participating in municipal works and employment or social inclusion “pacts”. The public employment services will be responsible for administering the scheme. Beneficiaries that fail to provide complete or updated information on their eligibility or to comply with the employment or social inclusion “pacts” risk penalties ranging from retrospective forfeiting of the benefit to up to 6 years’ imprisonment.

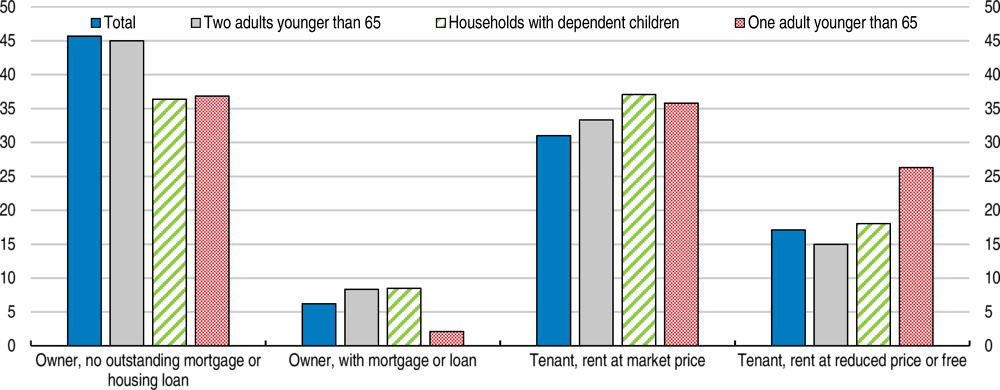

The Citizen’s Income transfers will be considerably more generous than the REI. For smaller households, it will be more generous than similar schemes in most other OECD countries relative to the national average income (Figure 1.23). Simulations suggest that the direct effects of the Citizen’s Income will reduce the depth of poverty by 25%, the poverty rate by 2.8% (when poverty is measured against a national relative poverty line), and inequality by 8.9% (when measured in terms of the ratio between the 80th and the 20th income percentiles) (Table 1.6). The income transfer alone is below relative and absolute poverty thresholds, but when the income transfer is combined with the rent or mortgage allowance the total transfer rises above some relative and absolute poverty thresholds for smaller households and those living in low cost areas (Table 1.4). At least one-third of households at risk of relative poverty rent a residence at market rates, while about 16% own their residence with a mortgage (Figure 1.24).

The Citizen’s Income’s transfer rules risk accentuating the tax and benefit system’s disincentives for low-income households to work, and could lead to poverty traps. The transfer is intended to ensure that beneficiaries achieve a minimum income, which is set at EUR 500 per month (without the rental or mortgage allowance). The transfer value is calculated as the difference between this minimum income and the recipient household’s existing income, allowing for some exclusions such as a carer’s allowance. If the household receiving a Citizen’s Income transfer starts earning additional income and remains eligible for the Citizen’s Income, the transfers would be reduced by 80% of the additional income until their Citizen’s Income employment or social inclusion “pact” expires. If they renew their participation in the programme, their transfer amounts would be fully reduced by the gain in income. These withdrawal rates are visible in Figure 1.26 (Panel B) as the net income (solid back line) remains flat as gross earnings rise up to 36% of the average full time gross wage for a single person. It is also evident in the high participatory tax rates at low wages – the effective tax rate from moving into employment (Figure 1.27).

The Citizen’s Income risks entrenching regional disparities in employment rates. In lagging regions, a larger share of the population will be eligible for the Citizen’s Income (Figure 1.28), but they face labour market and economic conditions that are likely to discourage them from gaining formal-employment income. Overall, the Social Security Institute (INPS) estimates that 45% of private sector employees in the South earn net labour income below the Citizen’s Income transfers (Commissione 11a del Senato della Repubblica, 2019[31]; Boeri, 2019[32]). For example, almost one-third of jobs in the South pay wages that are below the Citizen’s Income’s income eligibility thresholds of EUR 9 360 for a single person household who rents (Figure 1.8). At the same time, in lagging regions lower living costs (Figure 1.29) boost the purchasing power of Citizen’s Income benefits, in addition to there being more opportunities to supplement transfers with undeclared work.

The Citizen’s Income will particularly benefit single-person households, the unemployed and students (Figure 1.30). The Citizen’s Income equivalence scale is capped and below the cap it increases only modestly the benefits and income eligibility thresholds for larger households (Table 1.5). This limits transfers and imposes relatively stricter income-eligibility thresholds for larger households, even though absolute poverty rates are higher among larger households. This low scaling for larger households may encourage households to split, at least for the purposes of their Citizen’s Income applications, though the government is putting in place a system to discourage couples from legally separating to receive higher payments. Greece, which recently introduced a guaranteed minimum income programme similar in many respects to the Citizen’s Income, has experienced an increase in the numbers of households splitting. Greece’s scheme follows the Eurostat equivalence scale, which is somewhat more generous to larger households and does not cap the scaling of benefits. The share of single person households accessing Greece’s programme is 10 percentage points higher than the national average, without other significant differences in the households’ needs. This experience suggests applications from single person households need careful verification. To discourage households from splitting, benefit parameters should be less generous to single households and more generous to larger households (Marini et al., 2019[33]).

Eligibility criteria limit the cost of the Citizen’s Income by excluding some households that would be eligible given their low incomes and assets. Recipients must have ten years’ residency in Italy and have been continuously resident for the two years before their applications. The government estimates that this restriction will exclude 87 000 households (6.5% of the total) that otherwise would be eligible, saving about EUR 0.5 billion from the cost of the programme. This restriction will also exclude these households from benefiting from the Citizen’s Income employment and social support.

Requirements that beneficiaries participate in activation or other social support programmes, and in municipal work, are intended to help beneficiaries move into work and to counter the disincentives to gaining work income. Citizen’s Income beneficiaries will be required to complete an assessment of needs and then to engage in employment or social inclusion “pacts”. This is similar to the REI’s requirements and many other countries’ guaranteed minimum income schemes. Beneficiaries able to work will sign an employment “pact”, requiring them to engage in job search and training activities. They will be obliged to accept one of three “fair” job offers where ‘fairness’ is defined with respect to the job offer’s distance from the beneficiary’s residence. Beneficiaries will also be required to work 8 hours per week for municipalities’ social and development projects. For these requirement to be effective, job search and training programmes need to be effective and accessible (as discussed below).

The Citizen’s Income strict conditions and penalties, intended to encourage beneficiaries to enter work, may discourage take-up among the neediest population. Effective social protection programmes engage all eligible recipients, especially those with high needs, but this is a challenge especially when schemes are complex (Frazer and Marlier, 2009[15]; Bodewig et al., 2016[34]). Attaching punitive conditions to welfare benefits may discourage the households with the greatest needs from applying for or maintaining the benefit. Several assessments found that to be the case with the UK’s ‘Universal Credit’ reforms (Wright et al., 2016[35]; Work and Pensions Committee, 2018[36]). Highly vulnerable beneficiaries have greater difficulties both complying with job search, training and social programmes and demonstrating that they have done so, increasing the risk they either drop out or not apply for the Citizen’s Income (Crepaldi et al., 2017[37]). Following the UK reforms, the beneficiaries with the greatest needs (the homeless, mentally ill and those with poor literacy) were least able to meet benefit conditions, most likely to be sanctioned for failing to do so, and suffered most from those sanctions, even while those engagement conditions can also improve behaviour for other households (Batty et al., 2015[38]). Proactively engaging with potential beneficiaries, such as contacting them directly and guiding them through the programme’s application and requirements can be effective but requires tailored efforts that may be best undertaken by municipalities’ social services.

The cost of the Citizen’s Income is in line with similar schemes in other countries but it risks rising if beneficiaries do not move into employment as expected and the benefit’s take-up improves over time. The 2019 Budget allocates EUR 5.6 billion or about 0.3% of GDP to fund the Citizen’s Income, and between EUR 7.1 billion and EUR 7.4 billion annually from 2020. The REI, itself heavily expanded in July 2018, was allocated 0.1% of GDP in 2018 (European Commission, 2018[11]). The government’s cost estimates of the Citizen’s Income is consistent with OECD simulations using EUROMOD. It is within the range of other European countries’ guaranteed minimum income schemes (Baldini et al., 2018[39]). For example, Greece’s 2017 GMI, similar in many respects to the Citizen’s Income, is projected to cost near 0.4% of GDP when fully implemented (OECD, 2018[40]; European Commission, 2018[41]). The government expects the Citizen’s Income cost to decline in later years as beneficiaries graduate out of the scheme into employment. However, experience in Italy and elsewhere shows that awareness and participation in such schemes take time to grow. For example, in the early 2010s the municipality of Turin trailed a minimum income programme and found that it reached less than two-thirds of the eligible population. A similar share of the anticipated eligible beneficiaries had taken up the REI by January 2019. More than a year after Greece’s guaranteed income scheme was rolled out nationally, 60% of households in the poorest income decile had not applied (Bodewig et al., 2016[34]).

Flattening personal tax rates would benefit high-income households and involve high costs

Reducing taxes on lower incomes is a powerful instrument to achieve inclusive growth. Improving the incentives to work and to earn, particularly for people with lower skills and in lagging regions, requires adjusting the tax systems, along with benefits. Lowering the tax rate for low earners would bring Italy’s tax schedules closer into line with other OECD countries (Figure 1.17). The current government has considered simplifying Italy’s multiple personal income tax rates into two tax rates and rationalise tax expenditures while ensuring the personal income tax system remain progressive. However, the 2019 budget included no such proposals. Table 1.7 presents one hypothetical reform to the personal income system going in this direction and compares it the 2018 system.

The hypothetical flatter income tax, with the Citizen’s Income in place, would raise disposable incomes across household types, especially among high income households (Figure 1.25; Figure 1.26, Panel B). The ratio of the disposable income of well off households (those in the fourth quintile of the income distribution) relative to the less-well off households (those in the first quintile) would increase by 4.4%.

Flattening personal income tax rates would involve large fiscal costs. Simulations suggest a direct cost of EUR 61 billion annually, before accounting for changes in employment rates and productivity that would follow the reforms (Table 1.6). In addition, flattening the personal income tax rates risks entrenching social and regional disparities. For low income households, which may be near eligibility thresholds for the Citizen’s Income, flattening the personal income tax rates would not improve incentives for second earners to move into employment. For high income households, which are not eligible for the Citizen’s Income, reducing marginal tax rates and making them less progressive would further encourage households to increase their already high work hours, such as by second earners entering the workforce.

In-work benefits, a guaranteed minimum income and personal tax income reforms would boost employment and raise poor households’ income

This sub-section proposes a recommended reform package combining in-work benefits for low-income earners, a guaranteed minimum income with gradually decreasing transfers (as beneficiaries start working) and a simplified and progressive income tax system. The recommended reform package would adjust benefit rules and reform the personal income tax rate schedule to address the competing objectives of reducing poverty and encouraging employment within limited fiscal space. Like the Citizen’s Income, households who do not own their residence would receive an allowance for housing costs. Table 1.8 summarises the package. The recommended reform package would reduce income inequality and poverty by 10.5% and 8.6% respectively with respect to 2018 policies, and encourage employment and activity, at a net cost comparable to the Citizen’s Income (Table 1.6).

The in-work benefits included in the recommended reform package would provide additional income for low wage earners and ensure that beneficiaries’ net income rises as they earn greater employment income. This goes further than the existing system of tax credits. Among other benefits and credits, this would replace the existing low income tax credit and the EUR 80 per month fiscal bonus. This is visible in Figure 1.26 (Panel D) where the in-work benefits (light blue area) contribute to raise net income (solid back line) as gross earnings rise from zero to 50% of the average wage, resulting in low participatory tax rates at low wages (Figure 1.27; Box 1.5). This is in contrast with the Citizen’s Income (Figure 1.26, Panels B and C) where the net income rises little as gross employment earnings increase, resulting in high participatory tax rates (Figure 1.27). In-work benefits would raise employment rates and incomes of poor households at lower cost than transfer systems that impose higher participatory tax rates.

In Italy, an in-work benefit programme should assess eligibility on the basis of the individual earner’s salary level rather than their household’s total income. If eligibility is assessed according to household income (such as through the ISEE value) the principal wage earner may lose access to in-work benefits if the second earner starts working, even at low wages. This has been found to reduce work by the second earner, and to reduce the household’s overall employment levels (Brender and Strawczynski, 2018[42]). However, eligibility assessed according to household income would improve the targeting of in-work benefits to low-income households by ensuring that it does not benefit low-wage earners living in households with relatively high total income.

Reducing in-work benefits gradually as incomes rise would also improve incentives for beneficiaries with low incomes to increase their work effort and earn more. This approach would reduce the participation tax rate, the effective marginal tax rate and the tax wedge at lower and middle income levels, benefiting lower and even some middle income earners (Figure 1.26, Panel C). Macroeconomic simulations, based on Guillemette and Turner (2018[43]), suggest that reducing the tax wedge in this way, before taking into account other policies, would raise the employment rate by 2.6% in 2030 relative to 2018 policies, and lead to 2.4% higher GDP, which in turn would support public revenues. Strengthened active labour market policies and support for families would complement the positive effect of the recommended reform programme on employment and activity (Figure 1.31).

The proposed reform package would include a guaranteed minimum income for low income households. The transfers would be greater than those of the REI but somewhat lower than those of the Citizen’s Income for single person households. They would be scaled by more than the Citizen’s Income as household size increases and the scaling would not be capped. Overall transfers would decrease more gradually than under the Citizen’s Income as a beneficiary starts to earn income. Modest benefits that gradually decline as gross earnings rise would better address the trade-off between reducing poverty and encouraging work than the Citizen’s Income. Like the REI and Citizen’s Income, receiving the recommended reform package’s guaranteed minimum income would be conditional on participating in a tailored programme of job search and training programmes or other social support programmes.

The reform package proposes simplifying the tax system, notably by consolidating various tax credits into one that is linked to the individual’s income and the household’s structure. Along with the in-work benefits, the design of this credit would reduce the effective marginal tax rates for many households as they gain employment income at low wage rates. They would particularly reduce to negligible levels the participatory tax rate faced by a second earner moving into low-wage work (Table 1.6). The accompanying working paper (Bulman et al, 2019, forthcoming) presents the participation and effective tax rates. The relative generosity of the simplified family allowance and credit, with the guaranteed minimum income, would allow for the consolidation of other family benefits.

The recommend reform package’s overall fiscal cost is estimated at under EUR 8 billion in the short-term relative to 2018 policies (Table 1.6). This is similar to the 2019 budget estimate of the full-year cost of the Citizen’s Income. Within the recommended reform package, the guaranteed minimum income is estimated to cost about EUR 3 billion less than the Citizen’s Income. This estimate does not account for the boost to revenues entailed by higher employment rates, greater economic activity and improved productivity that the recommended reform package are expected to generate in the long term, underpinning the reform’s fiscal sustainability.

To support low income households while encouraging household members to seek formal employment, a growing number of OECD countries have adopted in-work benefits. These are also known as ‘make work pay’ policies as they provide a net income transfer to individuals or to households working a minimum number of hours and with employment incomes below specified thresholds. Designed correctly, these measures can improve employment rates, support the progressivity of the tax and benefit system, and reduce poverty. They can achieve this at lower cost for public finances than direct transfers to households. They can also be more effective at raising well-being for poorer households than increasing the minimum wage, which may reduce the number of low-wage jobs available.

The effects of the in-work benefits on employment rates and on redistribution are determined by whether eligibility and the size of in-work benefits are assessed against household as opposed to individual income and circumstances. Assessing eligibility against household income ensures that the benefit spending is better targeted towards poorer households. Studies of in-work benefits in various countries find that in-work benefits increase employment levels of primary earners. But assessing benefits against household income can create a high participation tax rate when the second earner starts working, as their income would make all earners in the household ineligible for the benefit. Overall this can lead to lower employment levels among second earners and lower employment for the household overall. Basing eligibility of in-work benefits on individual rather than household’s income and circumstance, as proposed in this Survey, has the advantage of generating stronger work incentives for second earners. This comes at the cost of poorer targeting of the benefit, as second earners who live in rich households and starting to work in low wage jobs would be able to claim the benefit.

Sources: Luca, Rossetti and Vuri (2014[13]), Eissa and Hoynes (2004[44]) Brender and Strawczynski (2018[42]).

Overall this section has shown that Italy can build on recent improvements in its social protection system to redress social and regional disparities by raising employment rates and incomes, and lowering poverty. Achieving this requires a reform package that provides a social safety net to low-income individuals while encouraging rather than penalising beneficiaries for moving into employment. A guaranteed minimum income combined with low-wage in-work benefits and reforms to the personal income tax can achieve this at modest fiscal cost. To be effective, tax and benefit policies need the support of effective administrative systems, capable of providing useful job-search and training policies as well as other social services.

Reforming social policies to support inclusiveness, productivity and growth

Strengthening employment services

Strengthening Italy’s public employment services (PES) is essential to improve job matching and labour market outcomes across the population. This has been made more vital by the PES having the lead role in implementing the Citizen’s Income. The PES play a small role in job matching (Figure 1.32) and lack the capacity and experience to administer a broad social protection programme such as the Citizen’s Income. Recognising these needs, recent government budgets allocated considerable additional resources to strengthen the PES’s capacity, including EUR 950 million over two years in the 2019 budget and rapid reform programmes are being developed. This follows the central government’s transfer in 2018 of EUR 235 million to regions for the PES. The increase in resources allocated to the PES is a positive step but a detailed multi-year plan on how to improve PES is yet to be defined.

Currently, Italy counts 550 public employment service centres, which are managed by regional administrations. Many of these centres, especially in lagging regions, lack the staffing and organisational capacity to fill their core employment service function (Figure 1.32), or to administer a programme as complex as the Citizen’s Income.

Citizen’s Income beneficiaries that enter an employment “pact” and many entering a social inclusion “pact” will be required to have ongoing engagement with the PES. The PES will need to be able to monitor and report on beneficiaries’ participation in their assigned programmes and take action if beneficiaries do not meet their obligations. In contrast, the REI operated through municipal social services, which would call on the PES to provide beneficiaries support with employment services, as part of a broader and package of tailored support. The Citizen’s Income encourages employers seeking staff to use the PES to fill their vacancies. If they hire Citizen’s Income beneficiaries through the PES, the employer will receive a rebate on their social security contributions.

Providing accessible and quality employment services across the country, especially in lagging regions, can contribute to reducing disparities and improving labour market outcomes for all people, including those not eligible for the Citizen’s Income (OECD, 2018[46]). Employment service capacity could expand faster if private employment agencies can complement the PES’ role in job matching. A trial programme provided job seekers with vouchers to use for employment services, including those provided by private agencies. The voucher’s value reflected the difficulty for the job seeker to find work given their characteristics. The Citizen’s Income rules restrict these vouchers to Citizen’s Income beneficiaries, excluding other job seekers, such as unemployment benefit’s recipients, reducing their access to employment services. Providing all unemployment benefit recipients with access to the vouchers may improve their prospects for finding work before their income loss leaves them eligible for the Citizen’s Income.

Improving coordination between ANPAL¸ the central agency responsible for overseeing regional PES, and PES is crucial to ensuing eligible beneficiaries can access the Citizen’s Income and receiving support to move into work. In 2017, regional and central governments agreed on minimum service standards, and regional governments must now provide performance data to ANPAL, which can identify where a region falls short. However, ANPAL lacks the power to enforce such standards as job-search and training policies fall within the remit of regional governments.

ANPAL needs additional power to strengthen regions’ PES services for the Citizen’s Income to produce results. For instance, ANPAL could have the responsibility of developing and implementing special restructuring programmes for those PES that repeatedly fail to reach the agreed standards. Such restructuring programmes could include management changes, structural reorganisation of PES and requalification of personnel. Strengthening accountability and incentives for regional PES to adopt best practice and improve performance would also help. Clarifying who is responsible for what and publishing data on the activities and performance of all PES would go in this direction, strengthening accountability and yardstick competition. Successful strategies also include making sufficient case staff available and disseminating information about the programme, even by directly contacting potential beneficiaries (Frazer and Marlier, 2009[15]).

Improving skills and training to support employment and formalisation

Encouraging on-the-job training is crucial to expanding employment and raising productivity and incomes. It can help workers move into the formal sector, especially when formalisation requires educational qualifications. Italy has achieved rapid expansion in access to adult skill education and training over the past decade. However, average adult workplace skills and training rates remain below many other OECD countries (Figure 1.33), especially in lagging regions (Figure 1.34). Stronger skills are in demand and approximately six out of ten jobs facing skills shortages are in high-skilled occupations (OECD, 2017[47]).

Technological change and automation, and Italy’s ageing population, add pressure to training systems, especially in lagging regions. About 15% of jobs in Italy are at high risk of automation and 35.5% may experience significant changes (Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[48]). Low-skill and low-wage jobs are at greater risk from automation (OECD, 2018[49]) and constitute more of the workforce in lagging regions. IT and computer skills are weak across the population. Population ageing leads to shifts in the demand for skills and for workers to adapt their skills as their working lives extend. In Italy, participation of 50-60 year old workers in skill training has risen but is still low.

The formal sector can invest in workers’ skills and readiness for new tasks and support formal employment by investing in on-the-job training. Strengthening apprenticeships is central, as has been outlined in previous Surveys (OECD, 2015[21]; OECD, 2017[22]). Training is particularly limited at SMEs, despite their skills needs. To improve workers’ readiness for vocational training and re-skilling, the government is implementing new measures to develop adults’ general and vocational skills (Box 1.6).

Italy’s Training Funds (Fondi Interprofessionali) are designed to support in-work professional training and can provide disadvantaged groups with access to training. Training Funds are less well-funded than equivalent schemes in other OECD countries and the government has reduced their resources since the crisis (OECD, 2019[119]). While there remain large gaps between JIPFs training offerings and skills needs, the gap has been closing. JIPFs’ role and management have been clarified by guidelines published in April 2018 by ANPAL.

Extending JIPFs’ purview from employed workers to the unemployed is welcome and can support participants’ entry into formal employment. This measure would be more effective if the quality of the courses and the skills gained by participants were certified, and if JIPFs were consolidated into funds linked with specific economic sectors. Stronger coordination with other stakeholders would better ensure that courses better reflect skills needs, and that programmes meet minimum operating standards.

Provincial Centres for School Education for Adults (CPIAs) were developed from the early 2010s to provide school-level learning to adults, as well as Italian language courses to immigrants. They provide sequential courses and recognise students’ progress through certificates and diplomas, including school-level diplomas. The Centres are usually organised by province and link with local authorities and the local labour market, and with regional educational institutions. 130 CPIAs operated across the country in 2018, and one CPIA in each region is mandated to research and develop adult education. A national monitoring system follows the centres and students, and found strong growth in enrolments, reaching 109 000 students, 14% of whom were aged 50 or older in the 2016/17 school year. Over 2 million Italians aged 25 to 64 have completed only primary school and 11 million have only a lower secondary school certificate.

Source: Benedetti (2018[50])

Lowering labour market informality and precarious employment

Increasing Italy’s share of formal and permanent employment would improve job quality. Workers in non-standard employment generally have lower productivity, lack opportunities to build their human capital, have more volatile incomes and are less protected from labour market risks (OECD, 2018[49]; OECD, 2018[46]).

A relatively large and growing share of workers are employed on temporary contracts and other non-standard arrangements (Figure 1.35). Also, the Italian statistical office estimates that 13.5% of Italian workers were undeclared in 2015, rising to 20% in lagging regions. In addition, about one in five Italian workers is self-employed, above OECD averages although the share has declined since the start of the recession (Jessoula and Pavolini, 2017[51]) About 8% of the workforce were ‘dependent self-employed’ in 2015, among the highest shares of any EU country (Williams and Lapeyre, 2017[52]). These workers who have the legal statue of being self-employed lack many of the employment protection and benefits of employees without enjoying the flexibility or autonomy of self-employment, as they have only one client and no authority to hire staff or take other strategic decisions about their operations.

Inclusiveness, equity and incomes in Italy would be supported by encouraging formalisation and employment in larger firms. Legislation passed in 2017 aims to strengthen protection for dependent self-employed workers, such as measures to improve work/life balance through access to parental leave or protecting workers on sick leave, although it is unclear how enforceable these measures will be in practice (European Commission, 2018[11]). A regulatory environment and tax and benefit reforms that encourage formal dependent employment may be more effective at reducing informality and precarious self-employment than targeted measures. These measures are likely to benefit lagging regions more, given their higher incidence of informal work and self-employment.

Firms and workers will formalise if they perceive that formalisation brings greater benefits than costs. Italy’s large tax wedge imposes a sizable cost to formalising, by reducing the income that formal employees retain relative to their employment cost, as well as lowering output (Akgun, Cournède and Fournier, 2017[53]). This adds to the costs of the regulatory environment and effectiveness of the public administration (OECD, 2017[22]).

The 2019 budget introduces a disincentive for the self-employed and small firms to grow and become part of larger organisations by decreasing the tax burden for low income self-employed and micro enterprises. The budget enlarges the simplified tax regimes (forfeit regime) available to self-employed and micro enterprises by raising to EUR 65 000 the income threshold taxed at 15%. The lower tax rate is applied to the gross turnover of the SME multiplied by a profitability index which is dependent on the firm’s sector of activity. The 2019 budget also introduces a reduced tax rate at 20% for SMEs with turnover between EUR 65 000 and EUR 100 000, effective from 2020, with the purpose of flattening the marginal tax rates when the turnover rises above the EUR 65 000 threshold. Simplified tax regimes and reduced tax rates for self-employment or small businesses need to be carefully designed to directly address any market failures that affect the intended beneficiaries, otherwise they risk adding to the system’s complexity or unintendedly discouraging businesses’ growth (OECD, 2018[49]).

Greater access to quality childcare would strengthen work incentives and improve wellbeing

Access to care for very young children raises women’s likelihood of seeking work (Olivetti and Petrongolo, 2016[55]; Figari and Narazani, 2017[56]; Tavora, 2012[57]). Also, childcare facilities improve children’s performance through the course of their education and can particularly benefit disadvantaged households (OECD, 2017[58]). When affordable facilities are not accessible, families turn to family members to care for children. This may be less pedagogical, and relying on this care makes relocating to other regions with better employment opportunities more difficult (OECD, 2017[58]).

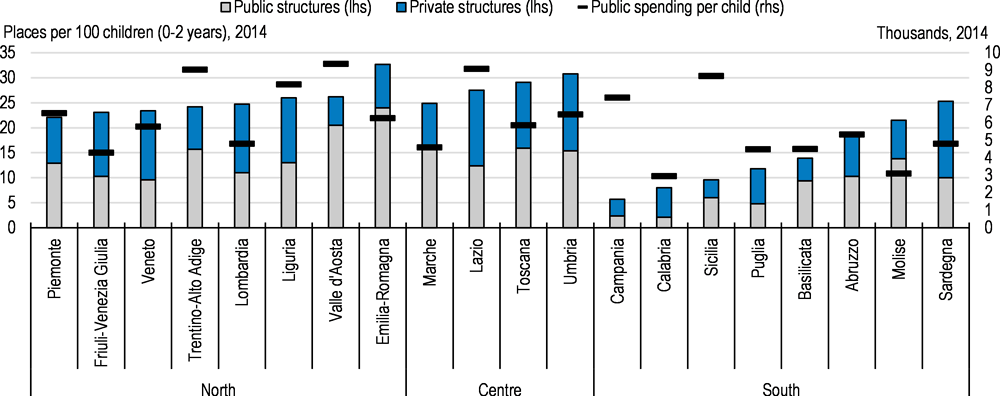

During the 2013/14 school year, less than a quarter of children under three had access to childcare facilities in Italy, less than in 2005 (OECD, 2017[58]). Far fewer places were available in lagging regions than in higher income regions (ISTAT, 2016[59]). The amount and share of total costs paid by parents vary considerably between regions, as does the total spending per child, which suggests that the quality of care varies considerably. From the age of three, children have access to 40 hours of free pre-primary education per week and all regions record near-universal enrolment.

Italy would benefit from following examples of other European countries which have expanded access to quality and affordable childcare (León and Pavolini, 2014[60]; Tavora, 2012[57]). These countries ensured that childcare places are widely accessible to all households, including those where the spouse is not currently in full-time employment, and that the places offer quality education and care for the children at a cost that is proportionate to the income that parents would gain from entering work (Colonna and Marcassa, 2015[12]). In Italy, a national plan was approved in late 2017 and established a national governing body to support, monitor and evaluate an integrated early childhood education and care system. It provides a small amount of additional funds to regions where enrolment rates are lower than the national average. Building on this step and monitoring its effectiveness are necessary complements to improve early childhood education while supporting families’ participation in the workforce.

Making regional development policy more effective to boost economic dynamism

Italy’s regional development policies have not been effective at narrowing the large north-south divide in terms of income and well-being. Lagging regions’ lower quality public administration hinders services for populations with the greatest needs, and impedes investments and productivity improvements. This section proposes possible remedies to tackle regional divides while underlining that increasing the efficiency of the central and local public administrations is a necessary condition for more effective regional policies and to provide the public goods and services that people and firms rightly expect.

Policies have failed to narrow the long-standing and large regional divide

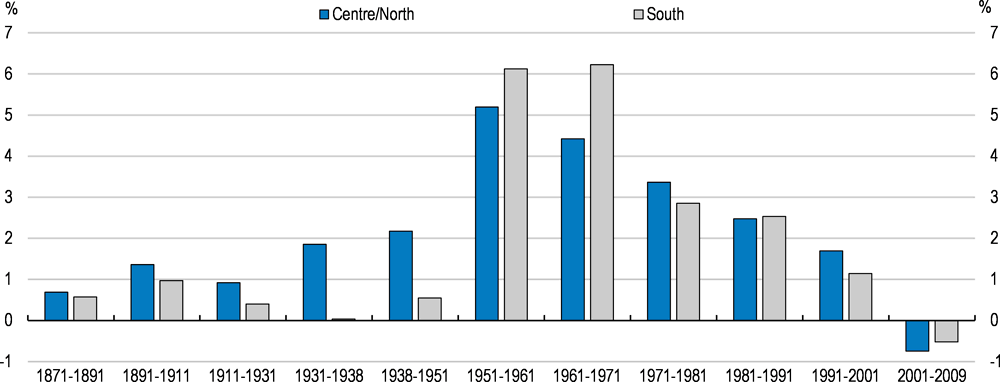

Italy’s geographical inequalities are deeply entrenched and the debate about their causes and remedies is as old as the Italy unitary state (Felice, 2007[61]; Federico et al., 2017[62]). Italian policymakers have attempted to address the “Mezzorgiono problem” since the early 20th century. After World War II, the government allocated substantial resources to southern regions through the Extraordinary Intervention for the South programme. This programme was implemented by the agency “Cassa per il Mezzogiorno” and then AgenSud. It lasted until 1992 (Box 1.7). The 1950s and 1960s was the only period since unification when GDP per capita of southern regions grew substantially faster than in the Centre and the North (Box 1.8).

As highlighted in the previous sections, differences in living standards between northern and southern regions are explained mainly by lower employment rates in southern regions. The Extraordinary Intervention for the South (EIS) programme and the “Cassa”, along with AgenSud (discussed in Box 1.7), failed to create the conditions for a self-sustaining convergence process in employment and productivity growth rates. There are two main reasons for this:

-

Firstly, focussing mostly on physical capital accumulation, the EIS failed to develop the technological and institutional capacity of southern regions. This would have required more investment in human and social capital, as well as other soft infrastructure, such as the efficiency of the public administration. Massive physical capital investment in the 1950s and 1960s failed to boost employment rates and entrepreneurship in southern regions (Felice, 2010[64]; Zamagni, 2010[65]).

-

Secondly, from the 1970s onwards, rising political interference and the curtailment of the autonomy of the “Cassa” led to resources being redirected from productive investment to redistributive programmes (Felice and Lepore, 2017[66]; La Spina, 2003[67]), contributing to halting the convergence process (Box 1.7). Moreover, the oil shock greatly diminished the comparative advantage of heavy industries, which was the basis of southern regions’ convergence.

The current institutions managing Italian regional policy were developed in the early 2010s (Box 1.8). Two agencies are responsible for regional development: the “Dipartimento per le Politiche di Coesione” (Department of Cohesion Policies, DCP) and the “Agenzia per la Coesione Territoriale” (Territorial Cohesion Agency, TCA) The DCP plans investment strategies and policies for regional development and convergence, spanning physical infrastructure, social investments, such as education and skills, and wellbeing. It acts through the Territorial Cohesion Agency (TCA), which leads monitoring activities and provides support to ‘managing authorities’ of regional and national development programmes. Also, in 2016 the government created a new political-level coordinating committee within the Prime Minister’s Office to facilitate the coordination of planning and monitoring of regional development funds among central and sub-national governments. Moreover, Invitalia – a company owned by the Ministry of Economy and Finance working in close cooperation with the Industry and Development Ministry – has responsibilities, among other things, to support the public administration for the effective management of EU structural funds. It also supports local cohesion policies developed by the public administration, and leads on public contracts.

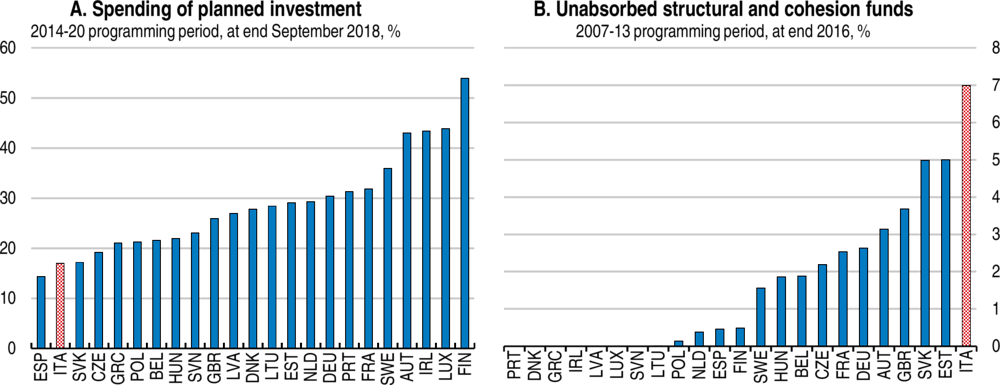

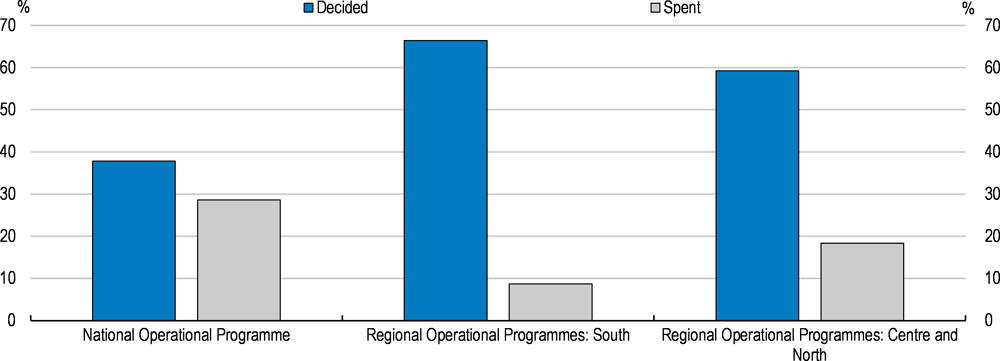

Despite these changes, deficient planning and coordination as well as long delays in project execution still hamper the effectiveness of Italian regional policies and the utilisation of EU cohesion and social funds (Figure 1.34). Commitments and payments relating to the 2014-2020 programming period proceed slowly. As at end-2018, for the 2014-2020 programming period commitments amounted to 30.4% of the total allocated funds for the whole country and payments to just 12.2% (Figure 1.38). Southern regions are performing considerably worse than central and northern regions (Figure 1.39). Spending has mostly involved improving processes and institutions to manage projects, not the realisation of projects themselves (SVIMEZ, 2017).

Delays in committing and spending the available funds have several causes. The central governments still lacks much needed coordination powers and capacity to formulate and implement a coherent regional development strategy, as highlighted in the previous Survey (OECD, 2017[22]). This problem partly stems from the constitution (Art 117) as it grants regional governments large powers on issues relating to regional development, such as national energy and transport networks. However, many sub-national governments, especially in lagging regions, still lack the capacity to plan, select and execute projects of high quality and on time. Projects in lagging regions, where public administration is less efficient, suffer from longer delays than in more developed ones (Court of Auditors, 2018[68]). Also, as is shown below, local public administration in lagging regions tend to be less efficient than in more developed regions.

Problems are not confined to sub-national levels. The shares of commitments and payments relating to the National Operational Programmes, which are managed centrally, are also low (Figure 1.39). By November 2017, the central government used only 42.5% of the funds shifted in the early 2010s – supposedly to accelerate spending – from the national co-financing quota of EU funds to the Actions and Cohesion Plan (Patto Azione Coesione, ACP) (Court of Auditors, 2018[68]).

Italian regional development policies started in 1904 with special legislation promoting industrial activities in Campania and infrastructure investment, mostly in Basilicata and Calabria). These early interventions were limited however; in addition, the onset of World War I altered government policies and in the inter-war period the “Mezzogiorno” problem stopped being seen as priority. Overall, from unification up to World War II the gap in living standards between northern and southern regions increased. In 1951, GDP per capita in southern regions (including islands) was 60% the national average compared with 88% in 1891 (Felice, 2010[45]).