Assessment and recommendations

This performance assessment review looks at the external and internal governance arrangements of Portugal’s Energy Services Regulatory Authority (Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços Energéticos, ERSE) and presents policy recommendations that aim to improve the performance of the regulator. The document builds on the work of a virtual peer policy mission that took place from 15 to 19 June 2020.1 It was presented for discussion by the OECD Network of Economic Regulators (NER) at its meeting on 17 November 2020.

ERSE is Portugal’s independent economic regulator for the electricity, natural gas and fuel sectors and the electric mobility network. It started operations in 1997 as the Regulatory Entity of the Electric Sector in tandem with the liberalisation of the Portuguese electricity sector. The regulator has provided stability and predictability to the sector over the years, and, thanks to its technical expertise and capacity, is highly regarded by stakeholders in the sector and is widely seen as a strong asset to the regulatory system. Over the years, the regulator has demonstrated flexibility and has been successful in taking on new roles. This has been matched by a proven agility to adapt governance and regulatory practice to new trends and challenges, most recently the COVID-19 pandemic. Agility will continue to be important in the post-COVID economy and more generally for the regulation of a rapidly changing sector, driven both by technological progress and policy for the decarbonisation of the Portuguese economy. In this context, ERSE will need to continue to be forward-looking in its decisions and strive to facilitate experimentation and innovation, while maintaining the strong sense of historic continuity, stability and predictability. Strengthened co-ordination and clarity of roles, as well stability of the regulator’s resourcing framework, will be necessary building blocks of this approach and will require increased dialogue with the executive. Finally, monitoring progress towards the regulator’s strategic objectives and communicating the results of its performance to a wide range of stakeholders will further demonstrate the value of ERSE and the merits of independent economic regulation.

Mandate

As Portugal’s economic regulator for electricity, natural gas, fuels and electric mobility, ERSE provides stability and confidence in the sector through transparent and predictable decisions. ERSE’s activity is most developed in the fields of electricity and natural gas regulation, in line with European legislation that has been adopted for these sectors over the last 25 years. ERSE’s objectives, clearly set out in legislation, are to: i) protect consumers; ii) ensure compliance of regulated entities with public service and other obligations; iii) ensure market integrity; iv) promote service quality; v) ensure competition between market players; vi) and resolve disputes between regulated entities and between consumers and market actors.

ERSE has approached the expansion of its mandate to the fuels sector effectively, overcoming several challenges. The law has expanded the sectors overseen by ERSE three times since its establishment: to natural gas in 2002, the electric mobility network in 2012 and the fuels sector in 2018. The new responsibilities in the fuels sector mark a departure from ERSE’s traditional work of regulating natural monopolies in network industries. In the fuels sector, ERSE is responsible for regulating downstream markets. Regulation in the oil products and biofuels sectors relies largely on ex post regulation, with the Competition Authority playing a major role until 2018. However, in the context of the energy transition, there are benefits to bringing fuels and biofuels within ERSE’s remit and it enables the regulator to have a holistic view of the different segments of the energy sector. The new role brought with it challenges of role clarity and co-ordination with other public bodies that were already active in the fuels sector, but ERSE has found workable solutions to overcome any ambiguity in legislation. The sustainable and predictable funding for this area of the regulator’s work nevertheless remains an issue (see Inputs section for further discussion).

The regulator has placed increasing emphasis on its consumer protection mandate in recent years with the liberalisation of the retail markets for electricity and gas. The Portuguese sector now counts 29 retailers in the electricity sector and 12 in the retail gas market, in addition to the suppliers of last resort. The regulator has a team dedicated to handling consumer complaints and mediating disputes between operators and consumers, and has focused on providing clear, plain language information to better inform energy consumers of their rights. It provides funding and training to arbitration centres throughout the country that handle consumer complaints in the energy sector. It also provides training to the household consumer associations that sit on its consultative councils in order to build their capacity and ability to contribute to deliberations. Stakeholders recognise and appreciate ERSE’s role in this regard. A recent survey commissioned by the regulator found that consumer support is seen as the area of ERSE’s activities that has been growing the most. A planned internal restructuring of ERSE intends to bring together consumer protection-related functions to strengthen the regulator’s work in this area even further.

Functions and powers

In general, ERSE has sufficient powers to carry out its functions, although there can be a time lag between gaining new responsibilities and the expansion of its enforcement powers. ERSE’s functions and powers include regulatory, advisory, mediation, supervisory and sanctioning (Table 1). The regulator currently lacks sanctioning powers in the wholesale energy, electric mobility and, to a lesser extent, the fuels sectors. The Energy Sector Sanctions Framework has not yet been updated to include electric mobility or the implementation of the EU Regulation on Wholesale Energy Market Integrity and Transparency (“REMIT”), while the latter gives ERSE supervisory responsibilities to monitor wholesale markets and investigate potential insider trading and market manipulation. ERSE is awaiting the transposition of EU directives into national legislation.

ERSE’s functions expand beyond national borders to cover the single electricity market with Spain, where it has advisory powers. ERSE is part of the Council of Regulators of the Iberian Electricity Market (MIBEL), created by an international agreement between Spain and Portugal in 2004 to address issues in the development of the single electricity market. The MIBEL Council is composed of the Spanish regulatory authorities for securities (Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores, CNMV) and energy (Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia, CNMC) and the corresponding entities in Portugal: CMVM (Comissão do Mercado de Valores Mobiliários) and ERSE. Market actors nevertheless raise concerns about insufficient regulatory alignment through MIBEL. Retail market regulations on either side of the border remain different, which can lead to different levels of business costs in the two countries. This can be challenging for cross-border market agents and can lead to different levels of consumer prices, impeding the functioning of a true single market. As the Council does not have executive power, its primary function is as a mechanism for information sharing. Draft regulation for the functioning of MIBEL, to be approved in Portugal or in Spain, are subject to the mandatory issuance of a non-binding co-ordinated statement of opinions by the Council.

Recommendations:

Advocate for the expansion of appropriate sanctioning powers to REMIT, electric mobility and fuels sectors. ERSE could capitalise on its knowledge of forthcoming EU legislation through its involvement in ACER and other European organisations to engage proactively with the government on developing national legislation that grants ERSE appropriate powers in a timely manner.

Argue for closer integration and harmonisation with Spain in the context of the Iberian market.

In the context of implementing the EU Clean Energy Package, particularly for retail-focused measures, ERSE could identify areas where it could take a common approach with CNMC to harmonise aspects of retail market regulation to facilitate market agents operating in both markets, to increase the level of competition and consumer benefits. Specific areas might include: regulations around smart metering, consumer information, billing requirements.

Consider establishing a cross-border consultative committee with representatives of industry, users and consumers on both sides of the border. This group could be tasked with identifying barriers to harmonisation and better outcomes for users/consumers and could be used as a sounding board for proposals and policies.

Strategic framework (vision, mission and objectives)

The regulator’s strategic framework is embodied in a four-year plan that would be strengthened by more focus on desired outcomes. ERSE operates within the framework of a four-year strategic plan (2019-2022) that sets objectives that span the regulator’s different activities. The plan is defined in a participative manner including different technical teams and senior management at ERSE. The plan sets five strategic objectives and 27 associated priorities (Table 2). The objectives are phrased according to the different activities that ERSE carries out rather than the outcomes that ERSE seeks to achieve. Many of the objectives and priorities are an aggregate of several priorities and responsible parties, which will make it challenging to monitor and report on them. The plan does not include performance targets and indicators, missing an opportunity to use it to define ERSE as an outcome-focused regulatory authority and to use the plan for strategic steering of the regulator’s activities and communicating on its performance. Recognising the value of such an approach, ERSE is working on defining indicators by strategic objective/priority (see section on Output and Outcome for further recommendations).

A more ambitiously and simply worded strategic framework would support ERSE’s identity as a forward-looking regulatory authority. The role of the regulator and its technical work are appreciated and understood by the regulated industry and other immediate stakeholders that sit on its consultative councils, but there is a lost opportunity with regard to projecting its vision and using its strategic framework to bring the message of its value to a wider audience (Figure 1). Moreover, ERSE’s forward-looking work (such as its use of regulatory sandboxes), in addition to its ability to provide predictability and consumer protection, could be more clearly captured in the strategic framework. For example, while the regulator’s strategic plan includes an analytical section on trends and challenges and the concepts of innovation and dynamic regulation appear among its strategic objectives, the vision and mission of the regulator do not articulate how ERSE fits into the “bigger picture” and contributes to driving progress in the energy sector.

Recommendations

Reinforce the strategic framework of the regulator by introducing more outcome-focus and more accessible language at all levels (Box 1). This can be undertaken for the next strategic plan of the regulator, building on an assessment of the current one and lessons learnt, to be defined in a participative manner including internal teams and sector stakeholders.

Phrase high level elements of the strategic framework (vision, strategic objectives) as outcomes that ERSE will focus on delivering, rather than descriptions of ERSE activities.

Devise the “vision” as a statement of a desired future (10-20 year time horizon) and the “mission” as a statement of what the regulator does.

Articulate how ERSE fits into the ‘bigger picture’ and can contribute to driving the sector forward in a context of rapid change. Make explicit the link between the regulator’s technical work and the value that this brings to the sector in terms that can be understood by a wide audience.

Accompany the strategic plan with clear, time-bound targets that can be monitored (see Box 2, and the Output and Outcomes section).

Devise and implement a communications strategy and plan for the vision and strategic framework of ERSE, with distinct activities and goals for internal and external stakeholders. The strategy will need a dedicated budget and resources for implementation.

Publish citizen’s summaries or Q&As alongside ERSE reports, studies and regulatory codes, using simple and clear language to communicate on the regulator’s activities to a wider non-technical audience.

Strengthen ERSE’s identity as a forward-looking regulatory authority by continuing to articulate its appetite for experimentation and flexibility, striving to push the frontiers.

Continue developing risk-taking and experimentation in the field of innovation, e.g. continued use of regulatory sandboxes, scaling up pilot projects, partnering with or increasing two-way conversations with industry on the process of innovation etc. (Box 4).

Carry out a risk-appetite mapping to identify areas where the organisation is willing to take more risks (Box 3). OECD Best Practice Principles on Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections (OECD, 2014[1]) also provide guidance on assessing risk and developing regulatory responses. It advises that: all enforcement activities should be informed by the analysis of risks; each activity and business should have their level of risk assessed and enforcement resources should then be allocated accordingly; and, each set of regulations should likewise be given a level of priority commensurate to the risks they are trying to address.

Australian Energy Regulator (AER)

The AER, and the other market bodies in the Australian energy sector, operate within a framework with an overarching statutory objective, known as the National Electricity Objective, which is to “promote efficient investment in, and efficient operation and use of, electricity services for the long term interests of consumers of electricity”.

This objective is referenced at the start of most documents and decisions produced by the AER, and is widely known across the industry. Within this framework, the AER as an organisation, also sets out a purpose and strategic objectives. The AER defines its purpose as working towards making “energy consumers better off, now and in the future”. The AER’s strategic objectives and its regulatory activities are designed in a way to advance the regulator’s purpose. This is explained in the strategic statement and in the annual corporate plan.

Source: Information provided by AER, 2020.

Essential Services Commission of South Australia (ESCOSA)

ESCOSA has a long-term objective defined as “the protection of the long-term interests of South Australian consumers with respect to the price, quality and reliability of essential services”, which is defined by legislation. On this, the regulator built its purpose statement of adding “long-term value to the South Australian community by meeting its objective through its independent, ethical and expert regulatory decisions and advice”. In its strategy document, ESCOSA goes further and defines the values which will enable it achieve its statutory objective, and thus guide its regulatory activities: responsiveness, accountability, innovation, and the building of inclusive relationships.

Source: Information provided by ESCOSA, 2020.

Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), United Kingdom

The FCA published in 2017 their Mission document, which is the framework within which the FCA takes strategic decisions, the reasoning behind the work undertaken, and the tools used to implement the regulation developed. Alongside an explanation of its regulatory remit within the scope of its three operational objectives, the FCA included in the Mission its decision-making framework which explains to the public how regulatory decisions are made within the remit of the FCA’s objectives.

Furthermore, through the Mission, the FCA identified five types of harm and mapped these across its operational objectives. Each year, it reports in its Annual Report how its regulatory and enforcement tools were used to reduce and prevent this harm.

ANEEL measures its performance using KPIs (or “strategic indicators”). These are linked to the strategic objectives which, in turn, are defined by ANEEL in its strategic planning or through legislation. A designated department (the Cabinet of the Director-General) is tasked with the monitoring of the performance indicators. Any ANEEL employee is able to consult at any time the performance of the indicators through a portal available on the intranet.

ANEEL has a total of 61 strategic indicators, linked to the 16 strategic objectives. Through the annual report, ANEEL provide an overview of its performance over time through the presentation of all strategic indicators and their comparison against the yearly targets.

The strategic indicators are categorised as follows, in order to cover all areas of the regulator:

7 strategic indicators for strategic objectives linked to results;

34 indicators for strategic objectives linked to processes; and

20 indicators for strategic objectives linked to people and resources.

Strategic indicators are designed to be all-encompassing, and to measure a wide range of aspects – both under the direct influence of the ANEEL, and the result of external factors. For instance, while ANEEL can directly impact the indicator on the timeliness of its regulatory decisions, the indicator on the average industry bond default rate is likely to be affected by matters outside ANEEL’s direct control.

The performance of each indicator feeds directly into the assessment of the strategic objectives. Therefore, the composite score of each strategic objective is calculated based on the scores of the individual indicators.

This is a tangible means for ANEEL to firstly internally monitor progress towards achieving its strategic objectives through scoring of strategic indicators, which in turn are used by teams with the aim to translate the objectives into tangible (and measurable) targets, and secondly to provide accountability to stakeholders through the Annual Report.

Source: Information provided by ANEEL, 2020; ANEEL Annual Report, 2019, https://www.aneel.gov.br/documents/653889/14859944/Exerc%C3%ADcio+-+2019/b755a474-25e9-994d-7f00-c8a6ec8d8b86.

Ireland’s Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU) developed a Risk Appetite Statement to articulate the level and type of risk that the regulator will tolerate while delivering its mission and vision. The statement forms a key component of the organisation’s Risk Management Framework.

The statement is intended to act as a guide to management indicating:

The areas where compliance is key and a risk averse approach is necessary;

How the regulator balances risk and opportunity in pursuit of value.

The main purpose of the Risk Management Framework is to integrate the process for managing risk into the organisation's various governance and operational processes. These include strategy and planning, management, reporting, policy development, and values and culture.

As part of the Risk Management Framework, the CRU has developed as Risk Appetite Statement, which states that the CRU overall has a conservative risk appetite. The CRU acts in accordance with this Risk Appetite Statement to achieve its strategic objectives. The CRU recognizes that it is not practical or desirable to avoid all risk. Accordingly, the CRU tolerates some risk, in pursuit of its mission and values. Acceptance of any risk is subject to ensuring that potential benefits and risks are fully understood and that measures to mitigate risks have been established. The Risk Appetite Statement establishes risks in a number of categories, and the CRU have considered a number of factors to determine its tolerance for each of these risks. The risk categories considered by the CRU are:

The Risk Appetite Statement is intended to be a living document. CRU reviews its risk appetite tolerances annually to reflect changes in the external environment.

Source: Information provided by CRU, 2020.

Ofgem launched in July 2020 their refreshed Energy Regulation Sandbox. This follows from the 2017 experience, when Ofgem worked with 68 innovators from the energy sector recruited through two sandbox application windows. Ofgem analysed the results of these sandbox cohorts, and published a report on Insights from running the regulatory sandbox. This not only provided the regulator with valuable insight on how to adapt the future Sandbox programmes, but also provided public accountability and gave future applicants further understanding of the process.

The Sandbox service complements current Ofgem reforms by allowing innovators to trial or launch new products, services, methodologies and business models without some of the usual rules applying. These can be rules that Ofgem controls (usually in licences) or, in some circumstances, from the rulebooks (codes) owned by industry, which underpin the day-to-day operations of the energy system. The Sandbox offers a range of tools to innovators across all the regulated areas, including suppliers, generators and network companies, or even those who are not directly regulated by Ofgem – for example third party intermediaries and energy services providers.

The use of Sandboxes in 2020 is considered an ideal time, as the energy system and consumer behaviour are evolving. As well as responding to the long term challenge of achieving net-zero, the Sandbox can help innovators and industry participants respond to nearer term challenges wrought by COVID-19, with consumer demand patterns changing as more people work from home, and more reliance on renewable generation due to lower levels of industrial demand.

The Energy Regulation Sandbox is run by the Ofgem’s dedicated Innovation Link team, which offers support on energy regulation to businesses looking to launch new products, services or business models and will act as the single point of entry for innovators who also wish to access the flexibility available in industry codes that have developed sandbox capabilities.

Source: Information provided by Ofgem, 2020.

Co-ordination

There are no permanent, sector-wide mechanisms for co-ordination between different actors in the Portuguese energy sector. However, the government establishes ad hoc groups that appear to work well. The ministry in in charge of the energy sector (Ministry of the Environment and Climate Action, Ministério do Ambiente e da Ação Climática (MAAC)) establishes working or expert groups on specific topics depending on need. ERSE participates upon invitation in such working groups.

ERSE counts on three independent consultative councils that in many ways play a significant role in supporting co-ordination between stakeholders from public authorities (including MAAC), consumer associations and industry. Although the councils’ primary purpose is to provide a consultation forum on the regulator’s decisions, they serve a secondary, indirect purpose of enabling multilateral discussions between the major players in the sector, as opposed to a one-way or bilateral consultation process between the regulator and its stakeholders. This is a source of great value to Portugal’s energy sector as it enables players to understand each other’s perspectives and develop relationships of trust over time. In this way, the councils provide stability to stakeholders and achieve consensus in their statements in an impressive 90% of cases.

ERSE is clear on its role and responsibilities vis-à-vis other actors in the sector and has taken proactive measures to address challenges of co-ordination when needed, but the division of responsibilities between entities is not always clear for regulated industry or the public. ERSE co-ordinates with a large number of organisations at national and international levels. The regulator is explicitly empowered and required through its statutes to co-operate with other bodies where this will assist in meeting common objectives. To overcome cases of ambiguity in responsibilities, ERSE has also established a number of co-operation agreements. Nevertheless, resolving overlaps often requires clarification on a case-by-case basis. ERSE has on occasion proposed new legislation when it has identified gaps or overlaps in responsibilities and maintains a record of institutions with whom it shares joint competences. While legislation defines the obligations for co-ordination between ERSE and other public agencies for providing non-binding opinions (e.g. with the Competition Authority, AdC) there are no mechanisms in place to ensure broader aspects of co-ordination such as information sharing. Moreover, the recent reorganisation of regulatory functions between ERSE, the Directorate General for Energy and Geology (DGEG) and ENSE appears to have sown confusion and the new division of responsibilities appears to be unclear.

The area of consumer protection requires particularly careful co-ordination given the large number of entities involved in handling complaints. Several organisations are potentially involved, including ERSE, ENSE, the Directorate-General for Consumer-Affairs, DECO (a private consumer rights association), the Economic and Food Safety Authority (ASAE) as well as nine independent arbitration centres. Most of the arbitration centres serve a particular region and they are not specialised in the energy sector; they cover all economic sectors and can only process complaints from households and not, for example, small businesses. Seven of the centres are partly financed2 by and receive training from ERSE. There is also disparity in type of mandate between different institutions involved in consumer protection: for example, the decisions of the arbitration centres are binding, unlike ERSE, which does not have the power to impose a resolution to a dispute. The large number of organisations involved could reduce consistency and predictability in decisions towards market agents, if each organisation follows different processes or interprets and applies rules differently. The system could also create risk to consumer harm as consumers may be confused or intimidated by the complex or unclear processes to bring a claim.

Recommendations

Assess which areas of work could benefit from having formal co-ordination mechanisms in place:

Consider establishing a formal co-ordination mechanism with the Competition Authority (AdC) that includes provisions for information-sharing. The co-operation agreement could cover points such as data ownership, what the information can be used for and for how long, and who has the duty to act on information that points to harm on competition, etc.

Invest in developing a strong understanding of the different operational roles of ERSE, ENSE and DGEG. This could be aided by simple solutions, such as using the same text on all three websites, to producing more detailed information, such as publishing an “approach to supervision” document to explain to the markets the current division of responsibilities within the sector, what types of entities can expect ERSE visits, and what ERSE will look at. Establishing a “one-stop shop” for data collection and administrative processes could also ease regulatory burden.

Advocate for an assessment of the effectiveness of the current consumer complaints system for the energy sector. The assessment could be mandated jointly by concerned public bodies and carried out by an external party. Such an assessment could investigate, for example, if all actors (households, small businesses, large businesses, etc.) have access to proportionate and specialised support in case of a complaint, if information on processes is made clearly available, if decisions are consistent across authorities and the country. If relevant and applicable, the conclusions of such an assessment could be used to rehaul, align or consolidate practices and mechanisms in the interest of all consumers in the energy sector (Box 5).

Ireland’s Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU) has responsibility for customer complaint resolution in the energy and water sectors.

The Commission has a statutory obligation (defined in legislation) to provide a complaint resolution service to domestic and small and medium business customers who have an unresolved complaint with their energy supplier or network operator. Only customers who have completed their supplier or network operator’s complaint resolution process, and failed to reach a resolution, may raise their complaint with the Commission.

CRU has the power to direct suppliers/network operators to resolve a complaint in a particular fashion. For example, the Commission can issue determinations and directions to suppliers and network operators, including the payment of a refund or compensation, where appropriate.

Final decisions are not subject to appeal and are binding on the energy supplier/network operator. However, customers are not obliged to accept the Commission’s findings and are free to take the matter further in another forum if they wish to do so.

CRU has a team of 5-6 staff dedicated to this function that is also responsible for reporting and consumer survey work.

Having responsibility for complaints resolution enables CRU to have visibility of the issues in the sector that can then inform the regulator’s decisions on whether to update its regulations in response. Having a single organisation interpreting and making decisions on the compliance of energy companies with regulations also increases regulatory predictability, reduces complexity in the system and simplifies the process for consumers.

Source: Information provided by CRU, 2020.

Input into policy making and relations with the executive and legislative branches

Given its strong technical capacity and expertise, ERSE opinions carry weight and are valued by the executive. ERSE has a formal advisory role and contributes to policy development through the provision of advice, non-binding opinions, studies and participation in working groups. The time that ERSE has to comply with requests can vary from a few days for the more informal requests to a month for formal requests. Its opinions to formal requests are made public via its website and in its annual report to ensure transparency. ERSE estimates that contributing to the formulation and refinement of policies, laws and regulations consumes about 10% to 15% of its total resources, mostly staff time. The regulator reports that this is manageable, although the burden can be considerable if several requests are received at the same time.

Transparent reporting and approval processes are in place but dialogue between ERSE, the executive and the parliament could be improved. The government defines the broad energy policy within which ERSE must act as an independent regulatory body. The government and parliament also approve the regulator’s annual budget and the respective multiannual plan, its balance sheet, and the annual report and accounts. Without prejudice to its functional independence, ERSE must keep the government informed of its regulatory activity, reporting on recommendations, legislative proposals and draft external regulations which it intends to adopt, as well as on instruments in the framework of the government’s general policy for regulated sectors.3 ERSE informs the member of the government responsible for energy in writing about the launch of public consultations, the submission of the tariff proposal, as well as of the approval of the tariff regulation and tariff decisions. However, beyond this there appear to be few institutionalised processes, such as a statement of expectations, to ensure close and effective dialogue between the regulator and the ministry in charge of energy (Ministry of the Environment and Climate Action, MAAC). Furthermore, on occasion the regulator has been taken by surprise by additional tasks or responsibilities included in the annual state budget, on which there has been no prior dialogue with or warning from the executive or the legislative.

Recommendations

Take steps to build a constructive, ‘no surprises’ relationship with the executive and legislative:

Set up a formalised and structured dialogue with the executive for each year. The objective of such a dialogue could help set expectations of work priorities and deliverables.

Request that MAAC send ERSE a letter during the preparation of the annual state budget that would highlight any new responsibilities that deviate from the approved multi-annual plan. ERSE could formally respond before the finalisation of the annual state budget.

Advocate for the creation of a policy initiatives forum hosted by government that convenes relevant authorities intervening in the energy sector (e.g. MAAC, DGEG, ERSE, ENSE…) to share planned policy changes, legislative changes or major supervisory actions (Box 6).

The Financial Services Regulatory Initiatives Forum is formed of the main five institutions which impact the financial services sector (Financial Conduct Authority, Bank of England, Prudential, Regulation Authority, Payment Systems Regulator, Competition and Markets Authority), plus the HM Treasury (government department) as observer member.

The Forum’s role is to improve information-sharing on the timing and operational impact of regulatory initiatives. The goal is to help manage the operational impact on firms from implementing these initiatives. The Forum is a mechanism for sharing information and supporting coordination between authorities – focusing on the timing of regulatory initiatives. The content of regulation remains the responsibility of individual Forum members. Reflecting this, the Forum itself does not have decision-making powers.

The public outcome of the work of the Forum is the Regulatory Initiatives Grid, which is published every 6 months, and which sets out the planned regulatory workplan over the following twelve months. It will help firms and other stakeholders understand – and plan for – the timing of the initiatives that may have a significant operational impact on them.

At the moment, the Grid is run as a 1-year pilot, and the Forum encourages industry and stakeholders to engage with it and provide feedbacks, so that its content and format can be amended so that it becomes as useful as possible for its users.

Source: Financial Conduct Authority, Regulatory Initiatives Forum, 2020, https://www.fca.org.uk/publications/corporate-documents/regulatory-initiatives-grid 2020; Financial Conduct Authority, Regulatory Initiatives Grid, 2020, https://www.fca.org.uk/news/press-releases/financial-services-regulatory-initiatives-forum-launches-grid.

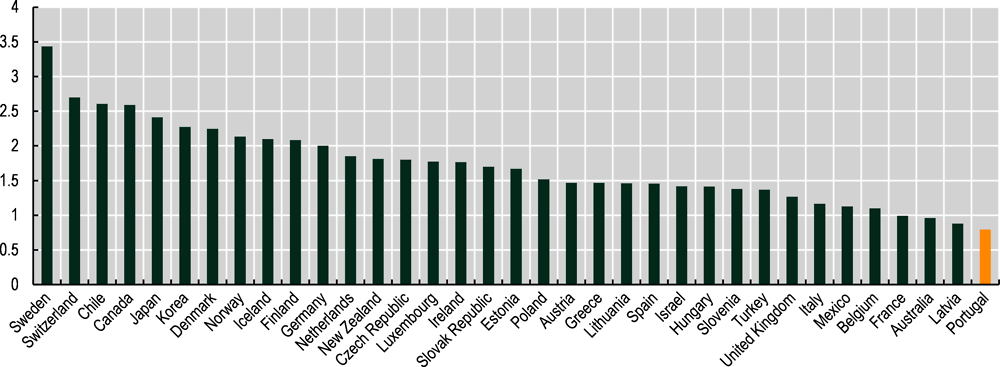

Independence

ERSE performs well on several dimensions of independence and has policies in place to foster a culture of independence internally. Nevertheless, it has been facing restrictions on its autonomy over financial and human resources. ERSE shows arrangements closest to good practice on independence4 among energy regulators in OECD countries as per the OECD Indicators on the Governance of Sector Regulators (Figure 2). The regulator also demonstrates independence in its technical decision-making, drawing on empirical evidence and transparent stakeholder input. The Board and Heads of Division and similar managers (ERSE senior management) provide independent leadership bolstered by post-separation employment policies such as a two-year cooling off period during which they cannot work in the regulated industry. During this period, Board members are compensated. Staff, however, do not have any post-employment restrictions. ERSE statutes, internal codes and plans also include provisions that deal with ethics, corruption prevention, incompatibilities and conflicts of interests. With regard to regulator resources, despite legislation that establishes the regulator’s de jure independence, provisions introduced through the annual state budgets have restricted ERSE’s autonomy in managing its financial and human resources in recent years (see Input section for more detailed assessment and recommendations).

Recommendation:

Establish an association or group of Portuguese independent regulatory authorities as a forum to discuss common challenges and opportunities and advance common positions when necessary (akin to the French “Club de Régulateurs”). This group could be used, for example, to discuss restrictions to financial and management autonomy faced by all Portuguese regulators.

ERSE is funded mostly by regulatory contributions from industry, and not by the government budget, providing a solid underpinning for the regulator’s financial independence. The vast majority (95%) of ERSE’s income comes from contributions (fees) paid by concession holders of the electricity and gas transmission networks,5 which are included in the network access tariffs paid by consumers (Table 4). The fees are defined by ERSE according to criteria set out in legislation. Since the expansion of the regulator’s responsibilities in 2018, ERSE also receives a small proportion of its revenue from fees paid by market agents in the fuels sector (2% in 2019, and 1.4% in 2020). ERSE’s finances are well managed; the external auditor’s reports indicate that ERSE follows sound financial management and budgeting practices and do not signal any major financial risks.

The regulator reports to have sufficient resources to meet most of its objectives although there is uncertainty in the funding for its fuels sector work. ERSE’s income has risen by 16% over the last three years, driven by contributions from the natural gas sector and new resources from the fuels sector. However, the regulator deems that the resources for the fuels sector work are insufficient. Furthermore, ERSE lacks budgetary autonomy and long-term certainty on this portion of its income. The government determines the amount of fees due from fuel sector actors according to a formula that it sets on an annual basis. This creates a degree of uncertainty on ERSE’s regulatory and financial autonomy and difficulties to plan beyond the current financial year for these activities. Although the fuels work represents a small proportion of ERSE’s overall budget, the current system for setting fees undermines the regulator’s financial independence.

In terms of human resources, ERSE benefits from an experienced, knowledgeable and technically proficient staff that is highly committed to the organisation. A new generation of staff recently recruited can bring in fresh ideas and perspectives as ERSE looks to the future. As of December 2019, ERSE employs 95 staff, 80% of which are professional staff, which is generally felt to correspond to the workload of the regulator. Stakeholders regard ERSE staff as technically highly competent. The most represented fields in ERSE are engineering (24%), law (22%) and economics (22%). Over a quarter of staff (26%) have been with ERSE since its founding (ERSE Annual Report, 2018), while 27% have been at the organisation less than three years. The coexistence of different “generations” of staff within the regulator may create challenges in terms of creating a cohesive “ERSE culture” but is an opportunity to bring in new ideas and ways of working and to position ERSE as a forward-looking regulator.

Lengthy processes for recruitment due to the need for government authorisation may reduce the regulator’s agility in bringing in new skills. Looking ahead, ERSE highlights the need to strengthen its capabilities in emerging fields (such as the energy transition, energy systems integration, energy communities, and circular economy), communication and support to market actors, behavioural science and data analytics. Since 2012, due to rules encompassing the Portuguese public administration, the regulator must request government authorisation to increase its headcount. As the approval process can take up to a year, this adds significant time to bring new staff on board and may reduce the agility of the regulator.

This restriction is symptomatic of a broader climate of constraints on ERSE’s HR and budgetary autonomy since the 2009 financial crisis. Portugal was deeply affected by the crisis, leading to an international bailout package and a period of intense austerity policies that affected the whole Portuguese public administration and independent regulators alike. Although ERSE’s budgetary autonomy is enshrined in its statues and in the Framework Law of Independent Administrative Entities, subsequent legislation introduced through the annual state budgets as a result of austerity policies curtailed ERSE’s autonomy in managing its resources to a certain degree. The restrictions apply to all public sector bodies including independent regulatory authorities in Portugal, although the latter are not funded by government budget. Some of these restrictions have been lifted in the last year or so, while others have been added more recently despite the general easing of austerity policies in line with Portugal’s economic recovery. Examples include:

In some instances, a portion of the approved budget not being released and unable to be spent without prior authorisation from the government body responsible for finance.

The government seeking to retain ERSE’s budget surplus for the state budget, rather than it being returned to energy consumers through the tariffs, as is foreseen in law.6

Limits on public procurement spending were introduced in the 2019 state budget, and had been included on occasion in previous state budgets.

Authorisation needed for the addition of new budget lines to ERSE’s annual budget, even those related to core functions of the regulator (e.g. for audits).

Salary cuts in 2009 and a freeze on salaries between 2009 and 2020.

Government approval needed for promotions (restriction removed in 2020).

Despite some restrictions, a level of autonomy in its management of human resources has allowed ERSE to weather this difficult period relatively well in terms of staff retention. Staff turnover averaged 4% between 2016 and 2019. The ability of ERSE to set its own salaries outside of public servant bands gives the regulator significant potential to attract and retain talent.7 Salaries at entry level are competitive compared to the Portuguese energy sector, becoming less so at senior levels. A higher turnover rate at senior management level (11% between 2016 and 2019) could be a reflection of this difference. ERSE also compensated for the inability to reward good performance with promotions and bonuses by offering other incentives, such as opportunities for training.

While restrictions appear to be easing, readiness for similar measures in the future is important given current economic forecasts. In a positive development, some of the budget restrictions that were in place in 2019 have been removed in the most recent state budget. Although it appears that austerity measures may be easing, the limitations that were imposed on regulators’ financial independence set a precedent. At the time of writing, the prospect of another recession following the novel coronavirus pandemic seems possible. It is conceivable that a government could introduce similar austerity measures in the future. ERSE’s experience of the post-2009 period could provide valuable lessons for how to respond should the situation be repeated.

Advocate for lifting of certain practices that limit the financial autonomy of the regulator and anticipate future challenges in post-COVID economy and effects on public finances. The regulator should contact the executive as part of a proactive stance to address practices highlighted the paragraphs above, and safeguard its HR & budgetary autonomy in case of future austerity measures. As part of this strategy, ERSE could:

Strengthen direct engagement with the ministry in charge of finance on ERSE’s annual budget and activity plan ahead of their official submission for approval.

Collect information on the impact of the current and any foreseen restrictions on its ability to carry out its tasks effectively, and appraise the practical implications of this upon the sector and consumers;

Advocate for setting fees for the fuel sector on a longer-term basis, with criteria set in legislation;

Explain how ERSE delivers value for money (VFM), maximising the delivery of its objectives whilst minimising cost. For example, show how ERSE has embedded VFM criteria such as efficiency and effectiveness into the culture of the organisation (e.g. through the efficient use of cross-sector teams) and how a VFM strategy is taken into account throughout the decision-making process.

Work with other economic regulators and influential figures within the energy sector to publicly advocate for the importance and value of independent economic regulation and develop common positions;

Proactively communicate to key stakeholders such as parliamentarians the value of independent economic regulation jointly with other regulators as a pre-emptive strategy in case of future challenges to financial independence.

Encourage mobility of junior-to-mid level staff generally in the energy sector and other public bodies in Portugal and abroad, including in other regulatory agencies, as part of an overall drive to promote innovation (Box 7). Staff mobility could ensure a stream of fresh knowledge and ideas and a greater diversity of perspectives. This could be achieved through secondments or temporary placements as part of a professional development programme. Encouraging mobility is particularly important in the context of a relatively small country such as Portugal. ERSE may need to advocate for the removal of legal obstacles to recruitment or secondment from other parts of the energy sector (public or private) or secondments from other bodies.

Ensure that ERSE remains an attractive place to work and strengthen the culture of meritocracy, enhancing visibility and opportunities including for junior-to-mid level staff.

Develop a range of internal career options including non-management posts for specialised staff who do not wish to pursue management responsibilities.

Expand the system of opportunities for staff development such as training, publishing or presenting at conferences.

Collect data on salaries in the regulated sectors and other Portuguese regulators to enable benchmarking and ensure ERSE salaries remain competitive with comparable agencies, particularly at senior levels.

Harness the performance evaluation system to reward good performance with career progression, complementing the incentives that are already in place such as training opportunities.

Encourage staff mobility within the regulator, taking the opportunity of the restructuring as a first step. For example, ERSE could carry out a ‘call for interest’ exercise so that staff can indicate if they are interested in moving teams. A more formalised mobility programme could be envisaged for the medium-to-long term. In general, ERSE could advertise all openings (internal and external) to all staff.

Implement measures to bring together different “generations” of ERSE staff, in the interest of institutional culture and ownership for the values and strategic framework of the regulator. Concrete measures could include “buddy-up” programmes or mentorship schemes between long-standing members of staff and more recent recruits.

The ACCC and the AER see value in secondments as a tool for staff development and capacity building (enhancing knowledge, skills and experience) and for building understanding and closer relationships with peer and partner agencies and stakeholders. The ACCC/AER has a number of formal and informal secondment arrangements in place for staff at different levels including the following:

The ACCC has established a number of reciprocal secondment arrangements with other government agencies, including the Treasury and the Department of Communications. To deepen understanding and knowledge of the indigenous peoples of Australia, the ACCC has a formal arrangement for placement of selected staff in an indigenous community for six months. The ACCC also has secondment arrangements in places with its peer agency in New Zealand (the New Zealand Commerce Commission, NZCC). The current Chief Economist of the NZCC is on leave from the ACCC. The ACCC also hosts staff from other agencies from time to time, such as staff on secondment from the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission.

The ACCC (together with the New Zealand Commerce Commission) has a formal training and secondment programme to assist ASEAN countries as they seek to implement competition laws and to combat anti-competitive activities. This programme includes staff exchanges, expert placements, secondments and resident advisors between ASEAN countries and the ACCC/NZCC. Secondments and exchanges have occurred with the competition authorities of Singapore, Malaysia, Viet Nam, Laos, Myanmar and Indonesia, amongst others. ACCC Chief Operating Officer Rayne de Gruchy commented “CLIP activities, such as staff exchanges, are proving an effective way to share know-how among agencies, as well as developing mutual understanding and relationships that can help agencies become operational more quickly.”

At the more senior level, the ACCC has an arrangement for exchange of senior management with the Canadian Competition Bureau. The Chair of the ACCC, Rod Sims, has said about this arrangement: “Exchange programmes like this allow the ACCC to build partnerships with international counterpart agencies to share and develop knowledge. These relationships are particularly valuable when it comes to pursuing cross-border investigations”.

Similarly, the AER makes use of secondments to keep up to date with regulatory best practice and to build technical knowledge. The AER has organised staff exchanges with AEMO (the electricity system operator in Australia) and with a few international energy regulators. The AER has a formal staff exchange / secondment arrangement with Ofgem in the UK. Several AER staff have spent between 6-12 months at Ofgem. The AER has hosted several staff from Ofgem in return. The AER also has an exchange programme with IESO (the system operator in the state of Ontario in Canada), as part of an arrangement between the members of the Energy Intermarket Surveillance Group (EISG), the peak international group coordinating and sharing skills between energy market surveillance and enforcement bodies.

The ACCC/AER has developed a secondment policy covering the various practical and legal issues associated with secondments. As a general rule, when a secondment opportunity becomes available the opportunity is advertised to all staff along with the selection criteria and selection process. On the whole the ACCC/AER considers that secondments provide valuable opportunities for staff development and building understanding and co-operation across agencies.

Source: Information provided by ACCC/AER, 2020.

Governing body and decision making

ERSE’s three-person Board of Directors is selected through a transparent process that provides safeguards for independence. The board comprises a president and two members. Legislation establishes that board members must have adequate qualifications, recognised independence and technical and professional competence in the regulated activities. Of the three current board members, two were former ERSE staff and one was formerly the ERSE Tariff Council president. Board members are appointed by the Council of Ministers, following their nomination by the member of government responsible for energy and opinions from an independent appointments committee (CRESAP, the Public Administration Recruitment and Selection Committee) and the parliament. Although the opinion of the parliamentary commission is not binding, it appears to be a robust check on power: the appointment of a candidate to the board was once rejected following a negative opinion from the parliament.

A longer time required between Board appointments could support continuity and decouple the process from political cycles. Members are appointed for a term of six years, non-renewable, and appointments must be staggered, with a minimum period of six months between appointments. This provision opens the possibility for an entirely new board to be in place within a little over a year, which could undermine continuity in the regulator’s strategic direction and predictability in decision-making.

The board’s wide-ranging responsibilities and small size may reduce its capacity to focus on strategic matters. The Board’s vast responsibilities combine both strategic and executive functions, which is not unusual in the Portuguese context and in smaller regulatory authorities in other jurisdictions. Board members act as members of the senior management team rather than being at arm’s length from the operations of the regulator. The absence of the Director-General for Regulation post since 2017 or another executive management position results in the board engaging directly with heads of Division without the support of an intermediate level. The board has agreed a division of labour whereby each member oversees the work of particular divisions, and all divisions and offices report directly to the board. Board members are highly involved in the work of their assigned divisions. The board holds a weekly co-ordination meeting with all heads of division and each member meets weekly with their assigned divisions. This may undermine the Board’s ability to dedicate time to strategic, foresight activities.

Decision-making appears to be a highly efficient process supported by a digital tool that ensures internal transparency. External transparency mechanisms are more limited. Board meetings take place once a week and are preceded by an informal meeting during which members discuss issues and prepare for the formal meeting. The board uses a digital platform (“Portal do CA”) to manage the decision-making process, through which ERSE teams submit relevant items for approval, information or review. All exchanges within the decision-making process are recorded in the portal, although in practice board members will usually have discussed issues in person with the relevant head of division in the course of their regular meetings with teams. Decisions are taken by majority or by unanimous decision of the three board members. The president has the deciding vote. When the board takes a decision, the relevant head of division/manager is notified automatically through the portal. ERSE publishes the non-confidential versions of its decisions, sends them to its mailing list and may publish them on its website. ERSE does not publish the minutes of the board meetings.

Decisions are informed by internal and external inputs; external inputs provide valuable information and perspective that ERSE uses in its decision making. The board relies greatly on the technical input from ERSE teams and in particular the heads of division. Three independent, external bodies (the Advisory Council, the Tariff Council and the Fuels Council) provide non-binding opinions on all proposed regulatory decisions and also on corporate documents, such as the annual budget, in the case of the Advisory Council (see section on Engagement). The board places great importance on the opinions of the councils, which provides an important challenge function in the decision-making process.

Recommendations:

Invest in the Board’s strategic, outward-looking role, dedicating more time to monitoring future challenges and opportunities in the industry; continuing to foster constructive, cordial relationships with the executive and the parliament; and representing the organisation externally with aligned messaging.

Alleviate the Board from certain operational and management decisions, in order to free time for its strategy and policy setting duties.

Look for further opportunities to delegate decision-making. For example, create an executive position (e.g. COO) or assign the reinstated DG Regulation with responsibilities for operational and management decisions (e.g. performance evaluations, training and leave plans compliance, occupational health and safety, risk management, approving expenditure above certain thresholds…).

Rotate responsibility of divisions and areas of work among board members.

Advocate increasing the minimum time required between board appointments from six months to at least one year.

Introduce mechanisms to improve the transparency of the board’s decision-making to all stakeholders. For example, the board could publish summaries of its meetings, redacting any confidential or commercially sensitive information (Box 8).

Regulators have developed a number of tools in order to ensure transparency and accountability towards the industry.

Ireland’s Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU)

Prior to 2020, Ireland’s Commission for Regulation of Utilities (CRU) did not publish the minutes of its commission meetings. In response to a request for the minutes under Freedom of Information (FOI), the CRU reconsidered this approach, in light of its commitment to transparency in its decision-making. Following this review, the CRU has now started publishing the minutes of its weekly Commission meetings.

Source: CRU, 2020.

Brazil’s Electricity Regulatory Agency (ANEEL)

Brazil’s Electricity Regulatory Agency (ANEEL) has in place a number of measures aimed at promoting transparency of regulatory decision-making.

Board meetings

Agendas for board meetings are published at least 5 days in advance on ANEEL’s website. The public can attend a board meeting in person or watch a live-stream on ANEEL’s website. For each board decision, the act along with information about the vote and supporting documents are published in the Federal Official Gazette (Diário Oficial da União) and on ANEEL’s website. In addition, the video recordings of the board meetings are uploaded to ANEEL’s YouTube channel, so they can be consulted retrospectively by anyone.

Internal organisation and management

ERSE’s internal teams are organised by function rather than by sector, a feature that appears to give the regulator a certain degree of agility as it has taken on responsibilities for new sectors over the years. Such a structure may also help in terms of ensuring consistency of regulatory processes across sectors. The current exception is a small team that was created to work on ERSE’s new duties in the fuel sector, an ‘internal commission’ of four people (the National Petroleum System Installation Commission, CISPN).

A long restructuring process runs the risk of slowing down the implementation of activities and creates uncertainty for staff. ERSE is currently restructuring, a process that was scheduled to finish in 2020. The rationale of the restructuring is multi-faceted: to consolidate the consumer protection activities that are dispersed across different teams, to strengthen focus on particular areas (e.g. on innovation through an ‘Innovation and special projects’ office or on internal procedures with the ‘internal management’ office) and to create intermediate management positions within the divisions. The organisation by function rather than sector will continue under the new structure. Staff report that certain activities have slowed down in anticipation of the definitive implementation of the reorganisation. The lengthy process also appears to be creating some uncertainty among staff and runs the risk of instilling ‘reform fatigue’.

The recent expansion of the workforce may test the limits of internal processes that worked well previously. The regulator has grown significantly in recent years. Between 2016 and 2019, ERSE’s workforce increased by over 20% to 95 staff. Some internal processes that may require co-ordination between different teams (e.g. making requests for data to regulated entities) seem to rely on informal contacts and understanding between staff rather than codified processes or policies. This approach may have been adequate at a smaller scale and with a core of staff with long-standing working relationships. It may not be as effective in a larger organisation with a significant number of new staff. As the 2018 annual report shows, 27% of staff have been at the organisation less than three years. The second largest cohort at 26% is those that have been with ERSE since its founding. As part of the on-going restructuring, ERSE intends to create a team whose terms of reference will include improving the coherence of internal processes (the Unit for Internal Management). This team will play an important role in finding workable solutions to this challenge.

Recommendations:

Embed institutional renewal in the internal restructuring process and take the opportunity to strengthen the regulator’s focus on innovation and foresight.

Introduce the Innovation and Special Projects Office and include foresight functions in its terms of reference, to consolidate understanding on changes taking place in the sector. This office could report directly to the board and support its strategic function of looking at future challenges and opportunities in the industry. This office could bring in expertise from outside the regulator (e.g. academia, energy sector more broadly) for limited periods (e.g. 6 months) to work at ERSE on specific technical areas.

Establish “communities of practice” bringing together staff from across the organisation and from other public authorities and regulators interested in particular topics (Box 9). For example, there could be a community of practice on distributed energy or on the implications of electric mobility.

Respond to the evolving needs of the organisation as it grows.

Regulators have established communities of practice bringing together staff interested in particular topics as a way to share knowledge and stay abreast of latest developments.

Professional Networks at Sweden’s Post and Telecom Authority (PTS)

At the Swedish Post and Telecom Authority (PTS), several internal professional networks provide the opportunity for staff members from different departments and units to come together and discuss topics of mutual interest. The structure and set-up of the networks differ depending on the theme and purpose and may shift over time. Topics include workshop facilitation, competitive intelligence or simply providing a forum for all the lawyers in the authority to meet and discuss.

One of the more long-standing and established networks is themed around supervision. PTS is organised so that supervision of market actors takes place in different departments and based on different legislation and regulations. The Supervision fora is a chance for all staff members actively working on supervision to exchange views and ideas but also a way for PTS to try to ensure coherence in its processes across departments. Although the supervision is based to some extent on different legal frameworks, and there may be justified reasons for different approaches, the aim is to have coherent processes when possible.

The fora meets twice a year and in-between there are possibilities for exchange of information on ongoing cases or other interesting topics. Often there are external speakers invited as well, providing perspectives on supervision from other regulators or, for example, the Parliamentary Ombudsmen, that responsible for ensuring that public authorities and their staff comply with the laws and other statues governing their actions.

The fora is administrated by a group of staff members working on supervision in different departments.

Source: Information provided by PTS, 2020.

Communities of Practice at the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) and the Australian Energy Regulator (AER)

The ACCC/AER has several internal “communities of practice”. For example, there is a community of practice on distributed energy. The regulator also has internal “networks” which bring together like-minded people using specific tools or approaches. For example, there is a “Quantitative Analysis Network” that meets regularly to discuss and learn about tools and techniques for quantitative analysis (such as R, excel, python). An “Economics Network” meets to share issues and developments in economics.

Source: Information provided by ACCC/AER, 2020.

Regulatory quality tools

Ex ante assessments of regulations are not used systematically and there is no standard methodology for carrying out assessments, which could generate inconsistencies in approach. No formal ex ante assessment is mandatory for ERSE activities, except in some areas where they are required under European regulation.8 Although ERSE does not undertake systematic ex ante assessment of costs and benefits, every ERSE decision must be subject to formal hearings and must be accompanied by a justification document. The justification document may include scenario analysis, impact evaluation, explanation of the regulation’s intention, its legal framework, etc. There is no explicit proportionality requirement for ERSE to tailor the level of the assessment to the potential impacts of a new regulation.

Nevertheless, the level of detail used in the ex ante analysis depends on the type of decision and its general impacts. For decisions on tariffs and regulated companies’ revenues, the economic analysis is detailed and data on costs and benefits is usually included. Currently, each head of division is responsible for determining whether a cost-benefit analysis is needed and for coordinating the analysis. Generally, the benefits assessed in the CBAs amount to the costs avoided for the regulated sectors. The methodology does not tend to assess other types of costs and benefits, such as societal, environmental etc. or include equality and diversity assessments. A new unit (GGI) is currently being established in the context of ERSE’s restructuration that will review and develop internal processes and quality control procedures, including for CBAs.

ERSE undertakes ex post reviews within the tariff-setting process and at the end of a regulatory period (every 3 or 4 years, depending on the sector). However, these do not follow a standard methodology across all sectors regulated, and do not encompass sufficient regard as to the quality of the regulatory setting process or of the regulatory tools employed by the regulator.

Recommendations

Develop a standardised approach for and increase the use of regulatory impact assessments on new regulatory policies, proportional to the significance of the regulation, to boost the quality of regulation.

Include ex ante assessments in all justification documents prepared for stakeholder consultations. When doing so, care should be taken to use clear and simple language to facilitate access to a broad audience.

Put in place corporate processes and detailed guidance material to ensure a consistent approach to regulatory impact assessments. Certain regulations may not require a full-fledged, quantitative cost-benefit analysis. There may be synergies with work on-going at the central government level in the Technical Unit for Legislative Impact Assessment (UTAIL). UTAIL is developing an impact assessment methodology, giving technical support and providing training to ministries and other bodies from the public administration.

Identify all relevant direct and important indirect costs as well as benefits. Consider assessing a wider range of costs and benefits, such as societal, environmental as well as costs avoided for regulated sector. Similarly, equality and diversity assessments (e.g. assessments on the most financially vulnerable consumers) would help ensure that regulations do not disproportionately affect disadvantaged groups.

Develop a standardised and systematic approach for ex post assessments of ERSE regulations, together with a communications strategy which allows the market and consumers to understand the impact and effectiveness of ERSE’s economic regulations.

Audit, inspections and enforcement

The audit process is relatively more transparent than inspections, but neither process uses a risk-based approach. ERSE carried out 13 audits and 8 inspections between 2015 and 2019. Portuguese legislation does not require audits and inspections to be risk-based. The Framework Law of Independent Administrative Entities establishes that regulators shall carry out inspections and audits on an ad hoc basis, in execution of previously approved plans and/or whenever there are circumstances that indicate disturbances in the respective sector of activity (for example, complaints). ERSE has two categories of audits: one-off specialised audits triggered by the identification of potential non-compliance, and regular audits, generally on an annual basis. In the case of entities that are subject to the Tariff Regulation, ERSE approves an auditing and oversight plan containing the issues subject to periodic auditing. The plan does not include a calendar of audits, but ERSE notifies regulated companies by letter well in advance that an audit is due to take place. Specialised audit firms selected by ERSE carry out the audits whereas ERSE carries out inspections itself. In the past, ERSE has had annual inspection plans but more recently has carried out inspections on a needs-based approach, based on data analysis and monitoring of the regulated companies. The regulator can also decide to take action because of consumer complaints. The ERSE website publishes reports on the outcomes of some but not all audits; it does not publish data or information on the outcomes of inspections (ERSE, 2020[2]).

Sanctioning procedures are transparent but the diverse legal frameworks that underpin ERSE’s sanctioning powers lead to different enforcement outcomes. In some sectors sanctions may not be an adequate deterrent. Stakeholders commend ERSE for its transparent sanctioning procedures. All procedures are public and searchable on request. ERSE can impose a wide range of sanctions, including warnings, fines and accessory sanctions.9 Under the Energy Sector Sanctions Framework10 the gradation of available sanctions is considered adequate to allow credible deterrence through the escalation of sanctions. The maximum fine is 10% of total turnover depending on the seriousness of the administrative offence for legal persons and 30% of total annual remuneration for natural persons, and can be doubled for repeat offenders. The Energy Sector Sanctions Framework applies to the electricity and natural gas sectors but does not cover fuels, electric mobility and the EU’s REMIT Regulation. Different legislation, in particular the special penalty regimes, confers sanctioning powers to ERSE in the other sectors. Fines are limited to a maximum of EUR 15 000 under the complaints book rules and EUR 44 891.81 under unfair trading practices. Several cases of repeat offenders indicate that the sanctions under these special penalty regimes are not a credible deterrent.

Recommendations:

Ensure inspections and enforcement are risk-based and proportionate. Decisions on what to inspect and how should be grounded in data and evidence, and results should be evaluated regularly (Box 10).

Advocate for change to sanctioning regimes to ensure sanctions are credible deterrent.

A number of tools can be implemented as part of developing a risk-based approach in relation to the inspection plan. For instance, the build-up of the risk table is a useful instrument which aids to the identification of priorities.

For instance, the approach in the table below was developed by the Health and Safety Executive England in order to determine the risk gap. This table matches the consequence and likelihood of the actual risk with the consequence and likelihood of the benchmark risk. In this manner, the regulator knows where to focus its efforts as part of their inspection activities. This leads to more targeted enforcement activity designed to counter the actual higher risk to consumers, as well as allows the regulator to identify areas of activity where a market actor might need additional guidance or education from the regulator.

Furthermore, an analysis of the areas flagged consistently as high risk over a longer period, enables a regulator to identify and investigate whether there are systematic deficiencies with the substance of the regulation, or with the interpretation of regulation by the market actors.

Engagement and transparency of engagement process

ERSE counts on several mechanisms for consultation that enable differentiated degrees of stakeholder engagement depending on the nature of the regulation. All decisions on codes and regulations must be preceded by a public consultation or a stakeholder consultation in the case of tariff decisions. ERSE also organises public hearings in the majority of regulatory reviews to promote more dynamic and interactive discussions. For particularly complex or sensitive issues, ERSE may conduct pre-consultations before the presentation of the regulation proposal in order to identify stakeholders’ main concerns. ERSE also has three independent advisory bodies – the Advisory Council, the Tariff Council and the Fuels Council – that provide opinions on all decisions.

The three consultative councils are constructive, transparent structures for engagement with major stakeholders that bring value to ERSE’s decision-making and to Portugal’s energy sector more broadly. ERSE consults on its various decisions with its key stakeholders through three independent advisory bodies that deliver non-binding opinions: the Advisory Council, the Tariff Council and, since 2019, the Fuels Council. All opinions of the councils are approved by majority vote, although if members do not agree with all or parts of the opinion of the council they can state this in the submission to ERSE. The opinions of the councils are made public and published on the ERSE website (ERSE, 2020[3]). If the opinions of the councils do not lead to a change in ERSE’s proposed decision, the regulator must justify why it is not making the suggested changes. The councils are an important space within the energy sector for stakeholders to gather and understand each other’s positions, in addition to the value that they bring to ERSE in terms of ensuring that its decision-making is more accountable and robust.

The councils include a wide variety of perspectives and membership bestows a privileged position to members. The councils are composed of members defined under the law including industry, consumer representatives, representatives from other regulatory entities or public bodies and, in the case of the Advisory Council, government representatives from both national and regional levels. Industry and consumer representatives must be represented in equal numbers. Members serve a renewable term of three years and many members have been on the councils for several terms. Membership was updated in legislation two years ago. Some segments of the energy sector are less represented (e.g. the renewable energy sector is not represented on the councils; ERSE has also struggled to engage with relevant players for its consultations on electric mobility11). Membership bestows a privileged position to members in terms of access to information on ERSE activities that may not be publicly available to all stakeholders at large. While there are some periodic and recurring procedures which occur at the same time every year, the Advisory Council has no advanced schedule of consultations available to its members or the public. Given the extremely important role of the councils, it is essential that they remain representative of the sector. There is a delicate balance to be struck between continuity (with the benefit of experienced, skilled presidents who can build consensus among all members) and ensuring that the councils remain dynamic and open to new perspectives.

Membership of the councils requires a significant commitment of time and resources given the growing workload. Councils provide opinions when requested by the ERSE president. Each council decides how often to meet in order to address these requests, but in general the work entails several meetings a month and sometimes several a week at the ERSE headquarters in Lisbon. Members are expected to travel to all meetings, including members based outside the Lisbon area such as representatives from the Madeira and Azores archipelagos (a three-hour flight in the case of the Azores). The organisations that members represent are not remunerated for their participation. However, in order to facilitate the participation of household consumer representatives, ERSE allocates a per diem to these members. Over time, the range of issues that councils discuss has expanded. ERSE sometimes asks councils to provide opinions on the same issue several times. Members of the councils may also submit opinions twice: once via the consensus opinion of their council and again from their organisation alone via the standard public consultation process.

Consultation through these formal channels is transparent. Information on interactions with stakeholders outside these processes is less accessible to the public. ERSE can hold meetings with stakeholders to hear from specific perspectives outside the broader public consultation process. ERSE does not publish a list of these meetings or their minutes. Separately, ERSE may have meetings with formal “support groups” composed of stakeholders, for which the documentation and minutes are kept for legal and administrative purposes. This information is not published, but can be accessed upon request (e.g. freedom of information provisions and right of recourse of administrative procedures).