Chapter 2. The history and current state of Community Education and Training in South Africa

This chapter looks at the former system of adult (basic) education and training that provided opportunities for South African adults to participate in education at the lower and upper secondary level. It also discusses the existing mass literacy campaign and second chance programme for upper secondary students wanting to obtain the National Senior Certificate. The key legislation and frameworks surrounding the new community education and training system are summarised to provide an overview of the current state of and vision for community education and training in South Africa.

2.1. Adult (basic) education and training

Since the start of democracy in South Africa, adult education featured among the policy priorities of the government.1 However, it was not until the 2000 Adult Basic Education and Training (ABET) Act that the adult education system was regulated. The ABET Act introduced learning and training programmes at level 1 to 4, with level 4 being equivalent to Grade 9 in the initial education system or NQF level 1 (see Table 2.1, for details on the levels). These ABET programmes are provided in Public Adult Learning Centres (PALCs) (which have recently been renamed as Community Learning Centres) and in registered private learning centres. Adults can obtain a General Education and Training Certificate: Adult Education and Training (GETC: ABET) at the NQF level 1. While ABET enrolment can help individuals prepare for the GETC: ABET, enrolment is not a requirement for taking the exam. According to Umalusi, the council for quality assurance in general and further education and training, around 56 000 GETC: ABET certificates were issued in 2016/2017.

The scope of adult education was later expanded to also include training at the Grade 10 to 12 level (i.e. upper-secondary education), changing its name from ABET to Adult Education and Training (AET). Adults can obtain a Senior Certificate (Amended), which is registered at the NQF level 4 (i.e. the same level as the National Senior Certificate (NSC), generally referred to as Matric).2 While the Senior Certificate (Amended) is very similar to the NSC, it does not allow graduates to continue to university.3 In 2016/2017, Umalusi issued just over 66 000 Senior Certificates (Amended).

The GETC:ABET and the Senior Certificate (Amended) are expected to be replaced soon by the General Education and Training Certificate for Adults (GETCA) and the National Senior Certificate for Adults (NASCA) respectively. The main difference between the GETCA and its predecessor lies in its curriculum, which will be better targeted towards adult learners. The NASCA introduces similar changes to its curriculum, and will allow graduates to access higher education (provided they obtain the required pass marks). The certificate is also more flexible: Participants may register for any number of subjects per examination sitting, provided they complete the qualification within six years. There are no minimum education requirements4 for the NASCA, but it is recommended to have a documented Grade 9 pass or a GETCA.5

2.2. Basic skills and second chance Matric programmes

The Kha Ri Gude Literacy Campaign managed to substantially reduce illiteracy among adults

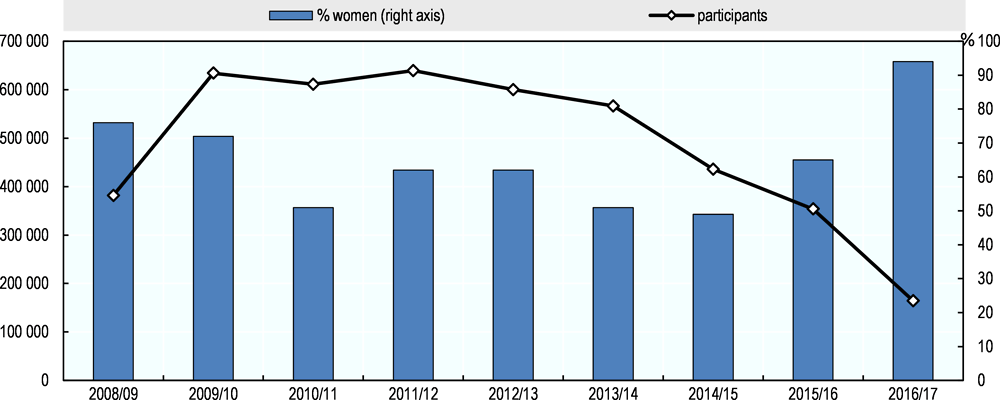

As a response to the low skill levels of many South African adults, the South African government launched in 2008 the Kha Ri Gude Literacy Campaign. The campaign is being phased out since the end of 2016/2017. The aim of the campaign was to reduce the illiteracy rate by 50% by 2015 (i.e. reaching 4.7 million people), as such empowering socially disadvantaged people to become self-reliant and able to participate more effectively in the economy. The programme provides 240 hours of training to all participants, free of charge. The focus of the training is to teach people to i) read and write in their mother tongue, ii) use spoken English, and iii) develop a basic number concept and apply arithmetic operations to everyday contexts. At the end of the training, participants should achieve an equivalence of Grade 3 in the basic schooling system (i.e. AET level 1, see Table 2.1). The programme also has a life skills component, which puts emphasis on themes that are central to the participants’ socioeconomic context, such as health or income generation. The campaign provides inclusive education, and specific efforts are made to target vulnerable groups, like women, old-age individuals, youth and people living with disabilities. With around 40 000 learning centres across the country, often in informal settings, the campaign has been able to reach learners from rural areas and informal settlements. In the period 2008/09 to 2016/17 the campaign reached almost 4.4 million South Africans (Figure 2.1), 62% of them being female, at a cost of ZAR 4.2 billion.

The Kha Ri Gude programme relies on volunteers to work as programme educators and facilitators. Annually around 40 000 volunteers were actively working on the programme. Only individuals with at least a Matric qualification are recruited as volunteers, and all volunteers receive basic training related to various aspects of adult education. The volunteers receive a monthly stipend, provided they meet certain criteria (e.g. submitting learner assessment portfolios). In the period 2008/09 to 2016/17 the programme created work opportunities for almost 350 000 volunteers, and 217 of them were awarded Funza Lushaka bursaries to obtain a full teaching qualification.

An extensive monitoring and evaluation system has been set up to ensure the effectiveness of the Kha Ri Gude campaign. Educators are monitored by supervisors, and these supervisors are in turn monitored by coordinators.6 In addition, participants are continuously assessed in literacy and numeracy, using learner assessment portfolios. These tests are marked by the volunteers, and further moderated and controlled by the supervisors and coordinators. The South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) furthers verifies a sample of the portfolios to ascertain the general integrity of the marking. Participants who successfully complete their portfolio receive a certificate at AET level 1, and are actively encouraged to register for Adult Education and Training at the primary and lower-secondary level (AET 2-4). (McKay, 2015[3])

The Kha Ri Gude campaign received several national and international awards, including the Unesco Confucius Prize for Literacy, acknowledging the innovative and inclusive character of the programme. The campaign successfully reached out to a large and diverse group of illiterate adults, and the average completion rate is higher than what is generally observed in literacy programmes (McKay, 2015[3]). In addition to helping to eradicate illiteracy, the programme also created work opportunities and income generation for a large number of volunteers, therefore contributing to poverty alleviation. Some negative points were, however, brought to light by a performance evaluation of the Auditor General of South Africa, including fruitless and wasteful expenditure, part of which was the result of fraudulent behaviour of a number of volunteer educators.

A second chance programme has been put in place to support students retaking the Matric examination

Over the last ten years, the National Senior Certificate (NSC or Matric) exam pass rate in South Africa increased significantly. In 2017, 75.1% of students who took the NSC exam passed it, compared to 65.2% in 2007. In an effort to further increase the pass rate, and hence the number of students that could potentially advance to further education and training, the Department for Basic Education launched the Second Chance programme in 2016. The programme provides free online learning materials, radio and television broadcast lessons, as well as face-to-face classes. The latter are only provided in areas with a sufficient number of students. The programme is available for four types of students:

-

Supplementary exam candidates: Students who failed at most two subjects during the NSC exam are allowed to retake those subjects in a supplementary exam. These exams take place three months after the initial NSC exam. In 2017, almost 125 000 students enrolled for the supplementary exam, but only 62% of them actually participated. The pass rate was low, with only 18% individuals taking the exam also obtaining the certificate ( (Parliamentary Monitoring Group, 2017[4])).

-

Progressed learners taking the multiple exam opportunity: Students who progress to the next grade without fulfilling all the promotion requirements are referred to as progressed learners.7 Progressed learners in grade 12 who perform weakly throughout the year are allowed the Multiple Examinations Opportunity, which gives them the possibility to spread their NSC subjects over two exam periods (November and June). In the first exam session, a minimum of three subjects must be taken. There were just over 107 000 progressed learners among the 802 000 Matric candidates in 2007.

-

Senior Certificate (Amended) exam candidates: Adults can obtain the Senior Certificate (Amended), a certificate at the same level as the NSC. See Section 2.1 for details.

-

NSC part-time exam candidates: Students who took the NSC exam for the first time over the previous three years and want to repeat one or more subjects, may register as a part-time candidate for the NSC examinations. Part-time candidates may not take more than six subjects in one examination round. This option allows students who failed one or more subject in their matric exam to repeat these subjects the next year, and combine the results from the two examination rounds. In 2017, 117 000 part-time candidates took the Matric exam.

Until 2016, a similar small-scale second change Matric Rewrite programme was run by the National Youth Development Agency, which recorded 21 000 participants over six years.

2.3. Building a Community Education and Training system

Acknowledging that the provision of education and training opportunities for adults and young people who dropped out of school before completing was inadequate, the Department for Higher Education and Training’s (DHET) Green Paper for Post-school Education and Training articulated the idea of creating a community education and training system (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2012[5]). The Green Paper argues that the Adult Education and Training (AET) system does not satisfy the needs of adults interested not only in completing their schooling, but also in acquiring labour market or sustainable livelihood skills. At the same time, the AET system does not harness the potential for development and social cohesion that exists in some community and popular education initiatives. To address these issues, the Green Paper proposed to develop a Community Education and Training (CET) system that would absorb the public adult learning centres (PALCs) and gradually expand to other skills programmes.

The ideas from the Green Paper were, after public consultation, further formalised in the 2013 White Paper (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2013[6]), which sets a goal of 1 million students in CET institutions by 2030 (compared to 265 000 students in public adult learning centres in 2011). The main features of the CET system are described as:

-

Role: Facilitate a cycle of lifelong learning in communities by enabling the development of skills (including literacy, numeracy and vocational skills) to enhance personal, social, family and employment experiences. Assist community organisations and institutions, local government, individuals and local businesses to work together to develop their communities by building on existing knowledge and skills.

-

Setup: Multi-campus institutions that cluster the PALCs. Other campuses will be added where necessary based on enrolments and programmes.

-

Curriculum: CET institutions will build on the current offerings of the PALCs to expand vocational and skills-development programmes and non-formal programmes. Non-formal programmes will be geared to the needs and desires of local communities and their organisations, including community-based cooperatives and businesses

-

Cooperation with community institutions: CET colleges and their campuses should make an effort to draw on the strengths of the non-formal sector (particularly their community responsiveness and focus on citizen and social education), in order to strengthen and expand popular citizen and community education. They may enter into partnerships with community-owned or private institutions.

-

Teacher quality: A qualifications policy for adult educators will be put in place that describes appropriate qualifications and sets minimum standards for these qualifications. Universities and TVET colleges will be supported to develop capacity to train adult educators.

-

Funding: The DHET will provide the core funding of the colleges, including for core permanent teaching and administrative staff, and this has to be complemented by funds from SETAs, the National Skills Fund (NSF) and the private sector where appropriate and available. CET colleges may charge fees for some of the programmes that they provide, especially for those funded by SETAs, the NSF or the private sector. In general, as far as possible, youth and adults attending CET colleges will be fully funded, whether by the DHET or from other sources.

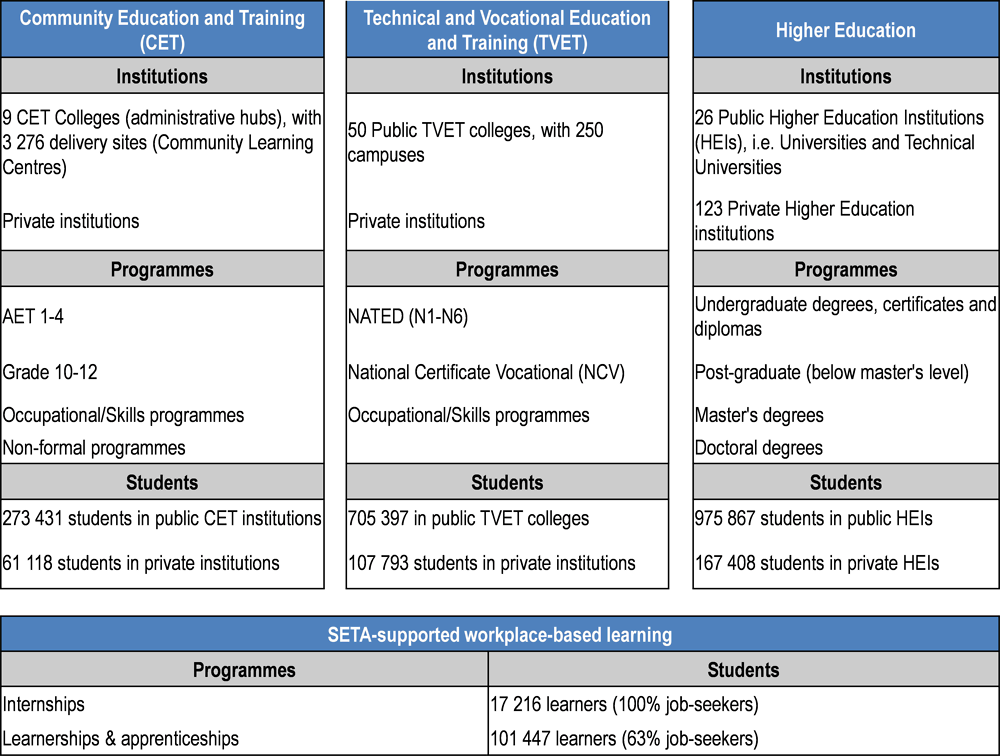

In April 2015 the first nine CET colleges were opened, one in each province, clustering the existing 3 276 PALCs. The PALCs were renamed as Community Learning Centres (CLCs). The nine colleges serve as administrative hubs, whereas the CLCs are delivery sites of CET. The long-term goals is to have a CET college in each of the 52 district municipalities, and a CLC in each of the 226 local municipalities. The CET system forms a third pillar in the post-school education and training system (see Figure 2.2).

Since the publication of the White Paper on Post-School Education and Training, the DHET has released (draft) policies and frameworks on a range of topics related to the CET system, including curriculum development, staffing norms, monitoring and evaluation, and student support services (see Annex A for a full overview).

In July 2017, the Ministerial Committee on the review of the funding frameworks of TVET Colleges and CET colleges published a report on the funding framework for CET. It concludes that the current adult education and training system is of very poor quality, and that the current mode of operation and available funding does not allow for significant quality improvements. A steady process of reform and incremental growth is needed, starting with a proper holding operation and a new CET implementation plan. The main recommendations from the report are described in Box 2.1.

In light of the forthcoming National Plan for Post-Secondary Education and Training, a Ministerial Committee on the review of the funding frameworks of TVET and CET was put in place. The poor outcomes from TVET and CET colleges have often been attributed to the fact that funding allocations have not kept pace with the increased number of students. The Ministerial Council concludes that more resources need to be mobilised from a variety of sectors in order for these colleges to play a more useful role in society. Their recommendations for the CET sector include:

-

Legislation: Once a sound conceptual model of the CET sector is developed it should be piloted and then a comprehensive Adult and CET Act should be developed (which is not simply a clone of the legislation relating to TVET Colleges.)

-

Structural reform and funding:

-

CET institutions should move towards a more community-oriented rather than school-based approach. There should be no admission criteria ensuring access to all who want to attend.

-

There needs to be a framework for institutional growth with due attention paid to the need for considerable funding for the effective development of this sector, as well as to more effective use of existing infrastructure and to its expansion.

-

Communities, local government and civil society bodies must be involved in the conceptualisation and development of the local CET institutions, including enrolment planning and the qualifications and programmes that should be offered, all within the context of the development of the regions where the institution is based.

-

A dedicated high level CET sector development support team should be set up to develop and monitor the implementation plans for each new CET institution and simultaneously undertake the necessary demographic and demand analyses to justify investment in CET institutions in those particular localities.

-

-

Setting the level of funding: The overall budget should be increased as fast as possible to at least 3% of the national education budget as an interim measure and certain percentages of the budget should be ring-fenced for personnel costs (including coordination), curriculum and materials, maintenance and monitoring and evaluation. Materials development should be a priority in the initial year or two. Building the capacity of the institutions to handle an increase in funding needs to be factored in.

-

Use of private and public facilities: Given the low likelihood of massive funding for new infrastructure in the near future, the state should encourage the use of spare capacity in public college and university facilities. Similarly, private non-profit facilities could also be used on fair contractual terms. In addition, the DHET should negotiate with municipalities to identify available facilities for this purpose, potentially in cooperation with the South African Local Government Association. There is also scope for the use of schools that have closed down.

-

Incorporation of the Kha Ri Gude structure into the CET system.

General recommendations include substantially increasing spending on the TVET and CET system, and limiting staff costs to 70% of the total budget. The report also highlights the importance of differentiation between TVET and CET colleges to avoid duplication.

Source: Ministerial Committee on the review of funding frameworks of TVET and CET colleges (2017[8])

References

[9] Aitchison, J. (2003), “Struggle and compromise: a history of South African adult education from 1960 to 2001”, Journal of Education 29, pp. 125-178.

[2] Department of Basic Education (2017), Annual Report 2016/17, https://www.education.gov.za/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/DBE%20Annual%20Report%202017.pdf?ver=2017-09-26-090956-673 (accessed on 23 March 2018).

[1] Department of Basic Education (2017), Kha Ri Gude Mass Literacy Campaign: 2008 to 2016/2017.

[7] Department of Higher Education and Training (2016), Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africa Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africaa, Department for Higher Education and Training.

[6] Department of Higher Education and Training (2013), White Paper for Post-School Education and Training.

[5] Department of Higher Education and Training (2012), Green Paper for Post-School Education and Training.

[3] McKay, V. (2015), “Measuring and monitoring in the South African Kha Ri Gude mass literacy campaign”, International Review of Education, Vol. 61, pp. 365-397, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-015-9495-8.

[8] Ministerial Committee on the review of the funding frameworks of TVET Colleges and CET colleges (2017), Information Report and Appendices for presentation to Minister B.E. Nzimande, M.P..

[4] Parliamentary Monitoring Group (2017), NSC 2016 examination results; Examination merge; Annual National Assessment (ANA) remodelling | PMG, https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/24590/ (accessed on 29 March 2018).

Notes

← 1. Before and during the apartheid regime, adult education was mainly organised informally, usually at the initiative of NGOs. See Aitchison (2003[9]) for a detailed overview of adult education in South Africa in the 20th century.

← 2. Before the introduction of the National Senior Certificate (NSC) in 2014, adults could participate in the National Certificate examinations. With the introduction of the NSC, which is limited to individuals of at most 20 years old, a gap was created for adult learners wanting to obtain an NQF level 4 qualification. This gap is currently (but temporarily) filled by the Senior Certificate (Amended), in anticipation of a new senior certificate targeted at adult learners.

← 3. As an interim measure, adults who obtained the Senior Certificate (Amended) can get an age exemption for university access.

← 4. There are a few minimum requirements that are unrelated to educational attainment: participants must be at least 18 years old, hold a valid South African document of identification and may not be enrolled at a public or independent school

← 5. Individuals who hold other NQF level 2 or 3 qualifications with languages and mathematics as fundamentals also fulfil the minimum prior learning recommendations.

← 6. Each supervisor monitors ten educators, and each co-ordinator monitors 20 supervisors.

← 7. In the South African education system, students may not spend more than four years in any particular education phase, and can therefore only fail one grade once. After that, learners are advanced to the next grade even if they fail the promotion requirements. There are, however, some minimum requirements in terms of attendance and performance.