4. Measures for minimising impacts of unused pharmaceuticals

Various measures can be taken along the lifecycle to minimise impacts of unused or expired pharmaceuticals. Table 4.1 depicts a number of policy interventions to reduce leakage, including waste prevention, collection and safe final disposal of waste, as well as end-of-pipe wastewater treatment.

Bekker et al. (2018[98]) estimate that approximately 40% of UEM generated in the Netherlands can be prevented.1 Improved disease prevention, personalised medication, precision medicine and improved dimensioning of packaging sizes all reduce the risk of accumulation and improper disposal of unused drugs in households. Each of these approaches, as well as possible policy measures, are discussed more extensively in the 2019 OECD report on Pharmaceutical Residues in Freshwater (OECD, 2019[3]).

Marketplaces for unused close-to-expiry-date medicines provide better matching of supply and demand and can thus prevent pharmaceutical wastage. Similarly, redistribution of unused medicines can avoid waste and can lead to significant economic savings. Bekker et al. (2018[98]) estimate that approximately 19% of UEM returned in the Netherlands would be eligible for re-dispensing.2

In most OECD countries, resale or re-dispensing of unused medicines is currently not practiced due to concerns regarding counterfeits, quality assurance and consequent legal restraints, but a number of initiatives exist (Box 4.1).

PharmaSwap in the Netherlands allows certified pharmacists to sell unused/undamaged medicines before they expire to other pharmacies who are in demand, often at reduced prices. The platform currently connects eight hospital pharmacies, 551 community pharmacies and eight wholesalers. Since its launch, it redistributed more than 3 500 packages and avoided procurement costs of more than EUR 600 000 by making more efficient use of pharmaceutical stocks (PharmaSwap, 2022[99]).

Sirum and Prescription Promise are two US start-ups that aim to collect and redistribute unused drugs to low-income patients and people in need. Donating patients and pharmacies can send in their unused medicines. Others can apply for these drugs by submitting a prescription form (Prescription Promise, 2020[100]; Sirum, 2020[101]). Similarly, the catholic social service organisation Caritas in Italy holds periodic collection events to collect unused medicines for redistribution to people in need.

In the Netherlands, a government-funded study is currently assessing the feasibility of implementing a re-dispensing process for unused novel oral anticancer agents. The study will redistribute medication that remains unused by oncology patients, and a first pilot includes 1 150 patients from four hospitals (ZonMw, 2020[102]).

Separate collection systems help avoid environmental leakage caused by flushing UEM in the drainage or by mixing UEM with solid household waste that is destined for landfill without leachate collection (Masoner et al., 2014[18]).

A variety of different collection schemes, take-back systems and stewardship programs are in place in OECD countries that aim to recover and manage waste pharmaceuticals. These can differ in many ways, including the scope of medicine waste covered, financing, collection routes, legislation and recovery efficacies. On-site receptacles at pharmacies constitute the most common collection system. One-day collection events or mail-back envelopes are also offered in some countries (e.g. United States). Some programs rely only on government funding (e.g. Australia) while others are financed by contributions from the pharmaceutical industry or from pharmacies that provide support on a voluntary basis or driven by extended producer responsibility (EPR) legislation.

Notably, not all OECD countries have implemented separate collection schemes for UEM, either because medicine disposal in households via mixed solid household waste is considered more cost-efficient (and still environmentally sound) (Box 4.2), or because the collection system is not mature enough to cope with additional small volume streams (see Annex A for a list of different collection schemes and approaches in OECD countries).

The environmental necessity of separate collection of pharmaceutical waste depends largely on the fate of mixed municipal waste (Figure 2.3). In countries where all mixed household waste is either destined for incineration in facilities with proper air cleaning and ash treatment, or in sanitary landfills with performant capture and treatment of the leachate, the risk for entry of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) in the environment is limited.

Nevertheless, even in mature waste management systems, throwing UEM in mixed household waste could raise health concerns related to the risk of abuse by third parties accessing household bins. The US Drug Enforcement Agency recommends to households in cases when no take-back programme is available to mix medicines with undesirable substances, such as used coffee grounds or cat litter before disposal in solid household waste to avoid misuse (DEA, 2020[103]).

The evaluation of environmental and health risks differs from country to country. Countries that deem the risks sufficiently important typically introduce a separate collection scheme for unused medicine. Other countries have decided that the limited environmental and health risks do not justify collecting UEM separately. The overview in Annex A highlights the divergence of national policies.

In Europe, the EU List of Waste (2000/532/EC) only categorises cytotoxic and cytostatic medicines as hazardous. Other unused medicines are not categorised as hazardous. The EU Directive 2004/27/EC, Article 127b requires EU Member States to “ensure that appropriate collection systems are in place for medicinal products that are unused or have expired.” (European Commission, 2004[104]). It is left to individual member states to determine whether separate collection through take back systems is necessary to ensure appropriate disposal. Most EU countries have opted for separate collection, but others such as Germany do not have a separate collection scheme at national level (Methonen et al., 2020[87]).

In Germany drug return schemes are only in place in some local areas. At the national level, it is recommended to dispose of pharmaceuticals in solid household waste, as all MSW is only landfilled after prior thermal treatment (NaWaM, 2020[105]). This approach is accompanied with information and awareness campaigns, informing citizens of safe household disposal routes in each region and discouraging the flushing of UEM (UBA, 2018[106]).

If separately collected, final disposal of UEM is ideally done by high temperature incineration (of at least 1 000°C), equipped with adequate flue gas cleaning, to ensure destruction or removal of the substances of concern (Methonen et al., 2020[87]; EU JRC, 2019[107]). However, some countries, where municipal solid waste incineration is pervasive and households are instructed to dispose of UEM through mixed household waste, consider that incineration at lower temperatures (typically 850°C or higher) is also safe. The EU Waste Codes only classify two classes of medicines as hazardous wastes, cytostatic and cytotoxic medicines (EWC code: 18 01 08) (European Commission, 2000[108]). However, some EU countries go beyond the European classification (e.g. Finland and Denmark classify all UEM as hazardous) and consequently require high temperature incineration for a larger share of UEM (Methonen et al., 2020[87]).

4.2.1. Voluntary collection schemes

In some countries, such as the Netherlands, drug take-back schemes are implemented in the form of voluntary approaches. Pharmacies and the pharmaceutical industry implement these systems driven by their corporate social responsibility commitments. Other motivating factors are pressure from consumers or pre-empting regulatory requirements (Box 4.3).

In the Netherlands, pharmacies are not legally obliged to take back leftover medicines from citizens. However, many pharmacies voluntarily act as a collection centre on behalf of the municipalities. Once collected, municipalities generally pick up the waste at the pharmacies and take care of its safe disposal (KNMP, 2020[109]). Surveys indicate that a majority of the population (54%) use the return scheme and dispose of unused medication via this channel (Reitsma et al., 2013[90]).

Similarly, in Finland pharmacies act as voluntary collection points. Municipalities provide waste collection bins to pharmacies and organise further treatment. It is estimated that 60-80% of unused medicines are returned to pharmacies by Finnish citizens (Methonen et al., 2020[87]).

In Poland, some municipal offices, health care centres or pharmacies voluntarily collect and dispose of UEM in special disposal containers financed by local governments. But the availability of collection points appears to be sparse, especially in smaller towns and rural areas (Rogowska et al., 2019[110]).

4.2.2. Government-funded collection schemes

In other countries, such as Australia, pharmaceutical waste collection is funded and organised by national or local governments (Box 4.4).

In Australia, the National Return of Unwanted Medicines Scheme (NatRUM), established in 1999, is a national program that collects unwanted medicine via pharmacies. While the pharmaceutical industry is aware and supportive of the RUM project, the program is entirely financed by the Australian Health Department. Collection rates have steadily increased and are now at around 60 tonnes per month (32 g/capita per year) (NatRUM, 2020[111]). However, awareness and use of the scheme are still limited; only 18% of respondents had heard of the NatRUM Project and the most common form of medicine disposal reported by Australian consumers continues to be the household bin followed by toilets or drains (Bettington et al., 2018[112]; Kelly et al., 2018[113]).

In Switzerland, pharmaceutical waste is classified as hazardous waste and should not be disposed of in normal household bins. UEM from households can be returned to the pharmacies or to designated disposal points. The funding of these schemes differs per Canton. In some Cantons the scheme is government-funded while in other Cantons pharmacies bear the cost, which can be passed on to the consumer.

4.2.3. Extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes for pharmaceutical waste

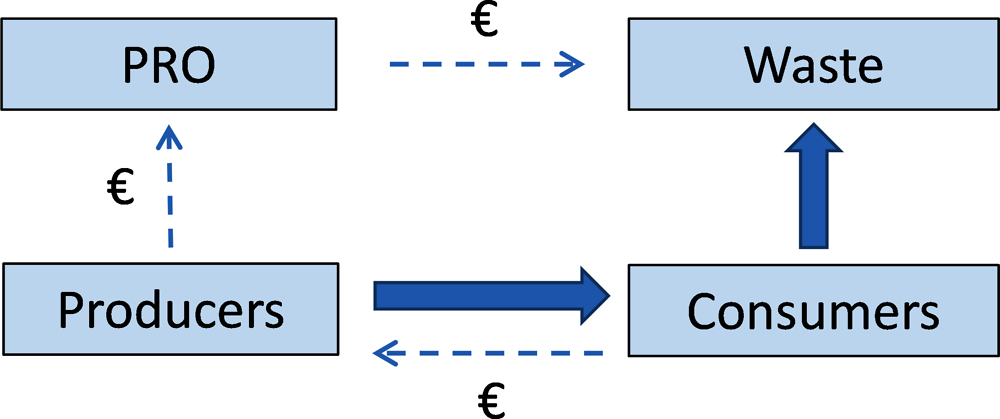

Several countries and provinces, such as France, Spain and Portugal have pursued an EPR approach to managing household medication (Box 4.5). By obliging pharmaceutical companies to collect and destroy unwanted pharmaceuticals that they have put on the market, EPR shifts the economic and organisational burden of unused drugs collection and disposal from the government to the pharmaceutical industry. As a result, EPR implements the “producer pays principle”, moving waste management costs from taxpayers to producers. Companies can internalise these costs in the price and can, in theory, provide services more cost-efficiently.

EPR systems in pharmaceutical waste streams are commonly organised as collective producer responsibility schemes (CPRs), where producers pay a contribution to a producer responsibility organisation (PRO), which manages the collection and safe disposal of UEM (Figure 4.1).

In France, pharmacies are obliged to collect unused medicinal products free of charge since 2007 (Legifrance, 2007[115]). Since 2009, pharmaceuticals are included in the national framework for EPR. Pharmaceutical companies finance the collection and disposal of unused drugs from households and pharmacies act as collection points. The ministry of environment gives a six-year accreditation to a PRO that organises the scheme. This mandate currently lies with Cyclamed (2022-27) (Legifrance, 2021[116]). Because of the mandatory participation, the program has a 100% subscription rate for pharmacies (22 000 pharmacies), pharmaceutical companies (191 companies) and pharmaceutical wholesalers (195 agencies). According to Cyclamed, 78% of all patients participate in the scheme and return unused medicines to collection points. In 2018, 10 827 (161 g/capita) tonnes of unused pharmaceuticals were collected and sent for incineration with energy recovery (Cyclamed, 2019[82]). The total cost of the collection scheme amounts to EUR 10 million and is financed by a contribution of producers of EUR 0.0032 per medication pack excluding VAT. The amount of unused drugs accumulating in French households has steadily decreased, from 878 g per capita in 2010 to 614 g per capita in 2018 (CSA, 2018[117]).

Sweden has a long tradition (since 1971) of returning unused pharmaceuticals to pharmacies. Originally, drug-return schemes were introduced by the Swedish monopoly pharmacy chain (Apoteket AB) for health security reasons. In 2009, Sweden introduced an EPR scheme for pharmaceuticals (SFS 2009:1031) including provisions for the take-back of left-over household pharmaceuticals.1 Unlike many other countries, the responsibility for financing and organising collection and safe disposal of UEM lies entirely with the pharmacies. The scheme is supposed to be financed by trade margins, though in some cases these are insufficient, and pharmacies carry the remaining costs.2 The scheme functions well and has achieved a high public awareness. In 2020, the total amount of medicines collected amounted to 1 400 tonnes (136 g/capita) (Swedish Pharmacy Association, 2021[118]).

In Canada, pharmaceutical waste management is organised at the provincial level. The first provincial EPR scheme was established in British Columbia in 1997 and similar programs have been developed in Manitoba (2011), Ontario (2012) and on Prince Edward Island (2015) (Government Manitoba, 2010[119]; Government Ontario, 2014[120]; Prince Edward Island Government, 2015[121]; British Columbia, 2017[122]). In the Canadian EPR systems, producers can either set up their own return program or sign up with a PRO. In Canada, the Health Products Stewardship Association (HPSA) is the only PRO currently managing pharmaceutical returns on behalf of pharmaceutical producers. The association is fully funded by brand-owners and contributions are based on market share. Retail pharmacies commonly act as collection sites. The Association has currently over 148 member producers and close to 5 746 retail pharmacies registered. It collected 433 tonnes of UEM in 2019 (20 g/capita) in these provinces (HPSA, 2020[123]). In other provinces, take back is managed by voluntary programs, which are funded by pharmacies, manufacturers or government agencies. For example, Nova Scotia’s Medication Disposal Program is a voluntary system run by the pharmacy association (PANS, 2019[124]). In Quebec pharmacies are obliged to take back returned UEM, but no EPR regulation is in place that secures the financing.

Similarly, the United States (US) does not have a national EPR drug take-back program, but an increasing number of mandatory programs (EPR) can be found at the state or local level. As of 2018, there were 25 local EPR laws in the US: 3 at state-level, 18 at county-level and 4 at city-level (New York Department of Environmental Conservation, 2018[125]). All of these are mandatory EPR programs and are funded by pharmaceutical manufacturers and run by MED-Project, the PRO, on behalf of pharmaceutical companies. The United States also has a national voluntary drug take-back program. The US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) organises biannual collection events, the “National Take Back Days.” The last two events in April and October 2021, recovered 420 and 372 tonnes of UEM (2.4 g/capita for 2021) (DEA, 2022[126]). Additionally, following a 2010 change in US federal law,3 DEA developed regulation allowing pharmacies to collect unwanted pharmaceuticals from households, and allowing them to utilise mail-back envelopes. Where no take-back program exists, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides guidelines on how to safely dispose drugs in household waste4 (FDA, 2020[127]).

← 1. Some pharmaceuticals, such as cytostatic and cytotoxic pharmaceuticals are classified as hazardous waste and are not covered by the scheme. Municipalities are responsible for collection, transport and disposal of hazardous wastes from households.

← 2. Based on an interview with the Swedish Pharmacy Association.

← 3. The 2010 “Drug Disposal Act” made it possible for public and private entities to develop secure and convenient collection and disposal systems and encourages them to do so on a voluntary basis (US Government, 2010[157]).

← 4. The “FDA flush list” indicates a list of 13 active pharmaceutical ingredients that can be disposed by a household by flushing if no drug take-back program is available. Flushing in these instances is endorsed to limit accidental poisoning and potential exposure to children and pets. According to FDA the risk of accidental exposure outweighs the environmental harm of flushing for all pharmaceuticals on the list (FDA, 2020[127]). The FDA maintains that the best disposal option for all pharmaceuticals, including those on the flush list, is via drug-take-back programs.

Collection rates differ among the schemes. For the countries where data was accessible, per-capita collection rates seem to be highest in France and Sweden, followed by Portugal and Spain (blue columns in Figure 4.2).

Pharmaceutical waste generation and collection rates also depend on the initial per-capita consumption. The ratio of collected waste and expenditure can be used as a rough proxy to inform about the effectiveness of different collection schemes (yellow dots in Figure 4.2).3 Sweden and France, with around 270 mg collected per USD spent, seem to be the most effective systems in collecting UEM. Portugal and Spain, with 200-220 mg/USD also perform relatively well. All four countries with high ratios have an EPR system in place with full and harmonised national coverage and with collection points at pharmacies. In Portugal, Spain and France, a producer responsibility organisation (PRO) collectively implements responsibilities of producers and organises the pick-up and disposal of collected waste medicines as well as the reporting, whereas in Sweden, pharmacies organise the collection individually. A share of the PRO budget is dedicated to awareness campaigns aimed at waste prevention and better patient compliance. Some countries (e.g. France) already witnessed a decrease in the collection rate due to waste prevention measures such as reduced prescriptions, precision medicine and better patient compliance.

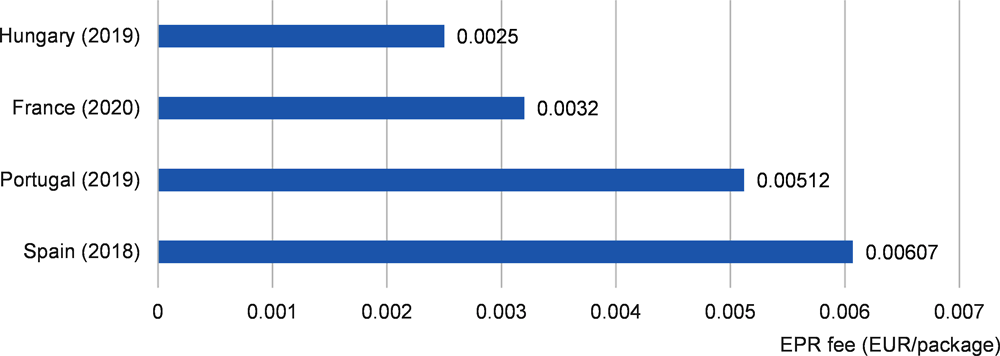

In most countries PROs are financed by contributions of pharmaceutical companies (producers) through EPR fees. The fees are charged based on market share, but methodologies and rates differ depending on national contexts. In countries where a per-package fee is charged and where this data was available, these ranged from 0.14 EUR cents per package in Hungary and 0.607 EUR cents per package in Spain. In some OECD countries additional EPR fees arise for outer packaging.

Assessing the efficiency and effectiveness of the systems in different countries is challenging due to the disparate conditions. Nonetheless, some good practices for a well-functioning pharmaceutical waste management system can be identified.

A sustainable source of funding is required to ensure the long-term operation of a scheme. Many countries structure funding responsibility along the “producer pays principle”, in form of an EPR scheme, with financial contributions from the pharmaceutical industry. In other cases, public entities (either municipalities or national governments) cover the cost of collection and treatment.

The responsibility for all costs should be clearly allocated. For example, clarifying who should carry the costs related to the role of pharmacies as collection points (dedicating commercial space, administrative costs and possibly also costs of disposal of packaging) is needed.4

Coherence of communication and harmonisation of systems is important to achieve compliance of users (citizens) and adherents (the industry). Since some countries manage pharmaceutical waste at the sub-national or municipal level, the multitude of different schemes can lead to confusion. For instance, in Canada some provinces have EPR schemes whereas others do not. In the United States a total of 23 different schemes currently exist at the state, county or city level. In the EU single market, each country sets its own approach.

Additionally, EPR systems should foresee mechanisms to deal with the risks of online sales of medicines. Online sales are creating free-riding opportunities as consumers are able to buy more easily from sellers in other regions/countries that do not always respect local EPR obligations. The use of mail-order medicines and online pharmacies (ePharmacies) has increased and the global ePharmacy market is projected to more than triple between 2018 and 2026 (Business Fortune Insights, 2019[132]). If no appropriate legislation is in place, ePharmacies could avoid producer/retailer/distributor obligations (and costs), whilst adding to the waste stream, undermining the financial stability of the EPR system.5

The limited awareness of consumers about proper disposal routes and drug take-back schemes weakens their impact on disposal practices in many countries (Box 4.6) (Paut Kusturica, Tomas and Sabo, 2016[96]). In a US survey, 45% of the respondents did not recall receiving information on proper disposal practices (Kennedy-Hendricks et al., 2016[79]). In Portugal, almost half of the respondents consider the current dissemination to be insufficient and would like to receive more information about existing disposal options (Winning Scientific Management, 2018[92]). In Latvia, 60% of respondents admitted to not being aware of how to dispose of UEM properly (Methonen et al., 2020[87]) and a survey conducted in the Netherlands concluded that 17.5% were unaware that liquid medicines should not be flushed (Dutch Sustainable Pharmacy Coalition, 2020[133]).

In Lithuania, awareness about the legal obligation of pharmacies to act as a collection centre for UEM, is limited and awareness campaigns are only scarcely available (Kümmerer and Hempel, 2010[21]). As a result, citizens often dispose of medicines along with their household waste (89% in towns, 50% in the countryside) or by flushing down the drain (8% of town residents). In the countryside open burning of pharmaceutical waste also remains common practice (Kruopienė and Dvarionienė, 2010[89]).

In Israel there is no mandatory legislation regarding the collection and disposal of household pharmaceutical waste, nor are there campaigns conducted to educate citizens about the safe disposal of pharmaceutical waste. Whilst UEM can be returned to pharmacies on a voluntary basis, only 6% of the interviewed citizens make use of this option, probably due to limited awareness (Barnett-Itzhaki et al., 2016[86]).

Information campaigns can increase the awareness and use-rate of take-back schemes (Box 4.7). When developing effective awareness campaigns the following considerations are important:

Target group: Identify the target group to customise the design and communication channels of the campaign. Elderly (>65 years) are the age group with the highest rates of medicine prescription and possibly also the age group where most drugs accumulate and/or expire. Additionally, Cyclamed, the French PRO, identified that motivating young people is a particular challenge as they tend to have relatively few drugs stored and visit pharmacies less frequently.

Information gap: The reasons for a lack of participation should be analysed before designing the awareness campaign. For instance, whereas solid pharmaceutical waste is more commonly returned to pharmacies, liquid drugs and creams seem to be more often disposed of via toilets and sinks (Braund, Peake and Shieffelbien, 2009[91]).

The #Medsdisposal campaign is a European initiative jointly co-ordinated by several European supply chain and healthcare organisations. The initiative aims to combat the negative impacts of mismanaged pharmaceuticals on the environment by informing customers about disposal routes and available take back systems in different European countries. This is complemented by media campaigns in different languages (MedsDisposal, 2021[134]).

The DUMP (Disposal of Unwanted Medicines Properly) Campaign conducted in New Zealand has been considered effective in educating the general public about the safe disposal of UEM. The Project is supported by different health agencies in New Zealand (SaferX, 2017[135]).

The German education campaign: “No pharmaceuticals down the toilet or sink!” is also considered a cost-efficient and effective information campaign (UBA, 2018[106]).

Other approaches can also lead to increased awareness and behavioural change. For example: special instructions for disposal that appear on the outer packaging of medicinal products or in the information leaflet; nudges such as ‘challenges’ or ‘saving accounts’ to return medication to pharmacies; and product ecolabelling to inform consumer choices (Table 4.3).

Doctors and pharmacists have a key role in prescribing and informing the public about safe medicine disposal practices. Therefore awareness campaigns and the availability of customised tools for health professionals can improve the overall awareness of the population. For example, advanced practitioner trainings and environmental classification schemes help practitioners to prescribe medication taking into account environmental criteria. The Swedish Association of pharmaceutical industry developed such a scheme, which so far covers around 200 APIs. There is interest to extend this initiative within the EU.

Notes

← 1. UEM was considered preventable when 1) larger amounts of medication were prescribed than needed for the expected duration of use; 2) excessive medication amounts were prescribed for a terminal patient; 3) a pharmacist dispensed more than the prescribed amount; 4) in case of a prescription error (e.g. wrong strength prescribed); 5) a refill that was no longer needed was dispensed; or 6) patients had side effects or insufficient effect of treatment at the moment of a refill, but still collected the medication.

← 2. In the study, returned medicines were considered eligible for re-dispensing when all of the following criteria were met: 1) the package was unopened; 2) the package was undamaged; and 3) there was at least 6 months between the return date and the expiry date.

← 3. Uncertainty exists about how much of the medicines bought are entering the waste stream. This indicator thus needs to be interpreted with caution.

← 4. For instance, in the Netherlands, municipalities generally cover the costs of disposal for pharmacies, though in 19 out of 355 Dutch municipalities (6%), pharmacies need to bear the costs themselves (KNMP, 2020[109]).

← 5. See the OECD Working Paper Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) and the Impact of Online Sales for more specific guidance on this topic (Hilton et al., 2019[158]).

![Figure 4.2. Per capita collection rates of pharmaceutical waste in selected OECD countries [g/capita] (blue bars), compared to expenditure (yellow dots)](../../../images/images/3854026c/media/figure4.2.png)