6. Students’ behaviour, expectations and well-being

On several measures, the well-being and life chances of Brazilian children have clearly improved. However, significant issues remain, and new challenges have emerged, many of which are linked to the COVID-19 crisis. This chapter draws on results from PISA, the TALIS questionnaire and national surveys to discuss student behaviours, expectations and well-being in Brazil, how they compare to benchmark countries, and the implications they have for learning. The aim is to help identify policies and practices that increase resilience, lower stress levels, enhance well-being and improve learning in the short-, medium- and long-term. This chapter will focus on three interrelated themes: first, the school environment and culture, which have a profound influence on students’ attitudes, behaviour and life chances. Second, students’ aspirations and perceptions. Third, their material, psychological, cognitive, social and physical well-being.

On several measures, the well-being and life chances of Brazilian children have clearly improved: infant mortality and child labour are now much less common, while participation in education and care has been rising (de Barros and Medonça, 2010[1]) (see Chapters 1 and 2). At the same time, as in many OECD countries (Burns and Gottschalk, 2019[2]) children are reporting more stress and anxiety, and less sleep (Pacífico, Facchin and Corrêa Santos, 2017[3]; de Assis et al., 2007[4]). Child obesity is increasing, bringing with it a host of potential physical, social and psychological challenges. Alongside all the challenges to educational progress documented in earlier chapters, the COVID-19 crisis has had some very direct impacts on the well-being of children. School closures and distance education modules may cause disengagement and psychological distress at a time when the economic downturn is pushing millions of families and children back into poverty, increasing the risks of malnutrition, abuse and drop out, as children are forced to look for jobs or take on unpaid care responsibilities at home.

This chapter will draw primarily on data from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), but also from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) questionnaire and national surveys to explore student behaviour, expectations and well-being in Brazil, how they compare to benchmark countries, and the implications for learning. The aim is to help identify policies and practices that increase resilience, lower stress levels, enhance well-being and improve learning in the short-, medium- and long-term.

Given that PISA is undertaken by 15-year-olds, our analysis will focus on issues students face as they transition from lower to upper secondary education, some of which are peculiar to adolescence (e.g. rising opportunity costs of staying in school) and some, such as disengagement from learning, that reflect earlier school experience.

This chapter will examine three interrelated themes:

The school environment and culture: children spend much time in school: following lessons, socialising with classmates, and interacting with teachers and other staff members. These are not just places where students acquire academic skills; they can also help students become more resilient, feel more connected with those around them, and develop life and career aspirations. These experiences have a profound influence on students’ attitudes, behaviour and life chances.

Students’ aspirations and perceptions: student perceptions of their own learning, abilities, and their future reveal much about motivation and ambitions, shaped by school, socio-economic context and family influences.

Students’ well-being: this refers to the material, psychological, cognitive, social and physical conditions that help students live a happy and fulfilling life. What happens in and outside school is key to understanding whether students enjoy good physical and mental health, and how satisfied they are.

This section uses data from PISA and TALIS to assess the extent to which the Brazilian school environment supports learning outcomes and student well-being. The school environment and culture encompasses, among other things, the disciplinary climate and instructional practices in classrooms and the social dynamics inside the school and in the surrounding community (Fraser, 2015[5]; Gislason, 2010[6]; Picus, L.O. et al, 2005[7]; Twemlow, S.W. et al, 2001[8]; OECD, 2013[9]). These elements can either support or hinder student engagement, well-being and academic outcomes. They also bear on teacher job satisfaction, and hence teacher recruitment and retention (Engeström, Y, 2009[10]; Thapa, A. et al, 2013[11]) (see Chapter 5).

Student truancy

High levels of student truancy in Brazil

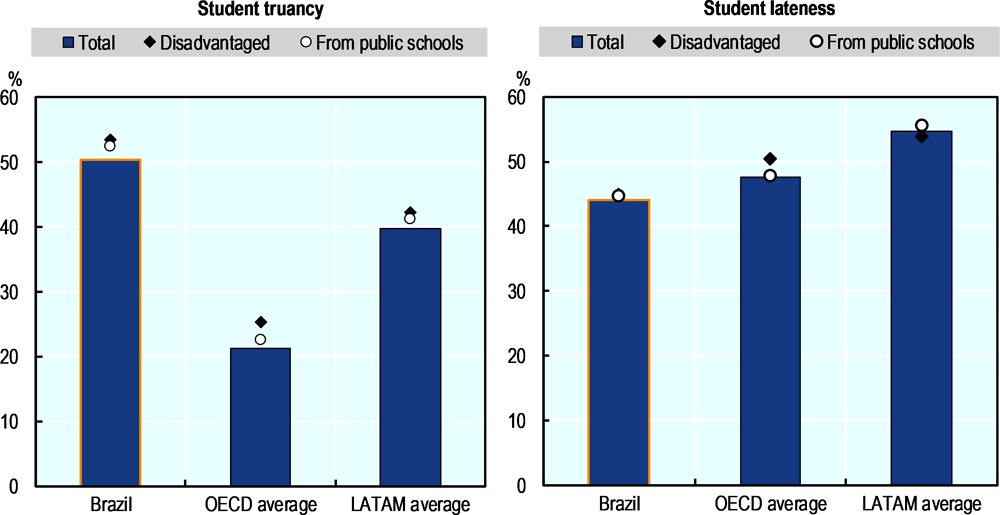

PISA 2018 asked students whether they had skipped classes or a whole school day and how often they had arrived late for school in the preceding two weeks (OECD, 2019[12]). The responses show that student truancy is twice as high among Brazilian students as it is across OECD countries (Figure 6.1). During the fortnight prior to the PISA test, half of the Brazilian students had skipped a whole day of school or some classes at least once (OECD average: 21% and 27%) and 44% of students had arrived late for school at least once during that time period (OECD average: 48%) (OECD, 2019[12]). The data also suggest that students from disadvantaged backgrounds and public schools tend to be more likely to skip school, when compared to their more advantaged peers. Truancy rates are also higher among those who have repeated a grade.

Several factors contribute to truancy. National evidence suggests that lack of motivation is one of the main reasons why students report skipping school. This is followed by the need to work and/or take care of family members (Exame, 2010[13]; Salata, 2019[14]; Schwartzman, Simon, 2005[15]). Moreover, research shows that victims of bullying often avoid school because they are too afraid or embarrassed (Townsend et al., 2008[16]; Hutzell and Payne, 2012[17]; ABGLT, 2016[18]).

Student truancy is associated with poor school performance

High rates of student truancy are one indicator that Brazilian students, and in particular disadvantaged students, are disengaged from school and their studies. Inevitably this affects learning. After accounting for the socio-economic profile of students and schools, students who had skipped a whole day of school in the two weeks prior to the PISA test scored 15 points less than students who had not done so. Skipping some classes was associated with a decline of 32 score points in reading performance; arriving late for school was associated with a drop of 23 score points, even after accounting for the socio-economic profile of students and schools (OECD averages: 40, 37 and 26 score-point decline respectively). In the medium to long-term, truants are more likely to fall behind in class, drop out of school, wind up in poorly paid jobs, have unwanted pregnancies, and even abuse drugs and alcohol (Aucejo and Romano, 2016[19]; Hallfors et al., 2002[20]; Smerillo et al., 2018[21]; Kimberly and Huizinga, 2007[22]). One challenge here is that it is hard to tell, in the context of a cluster of problems including truancy, weak school performance, and other challenges, which problems are the underlying cause.

If students who arrive late for school or skip classes fall far behind in their classwork and require extra assistance, the flow of instruction is disrupted, which may also hurt other students in the class, and damage the whole school system. PISA 2018 results show that on average, students scored 7 points lower in reading for every 10 percentage point increase in the number of schoolmates who had skipped school (OECD average: -8 score points), and 6 points lower for every similar increase in the number of schoolmates who had arrived late for school in the two weeks prior to the PISA test (OECD average: -6 score points), after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile and students’ own truancy or lateness.

School climate

Many Brazilian classrooms are not conducive to teaching and learning

For students to learn, teachers need to create a classroom environment that is conducive to learning, which means keeping noise and disorder at bay and making sure that students can listen to what the teacher (and other students) say and can concentrate on their work. PISA results suggest that this is often not the case in Brazilian schools.

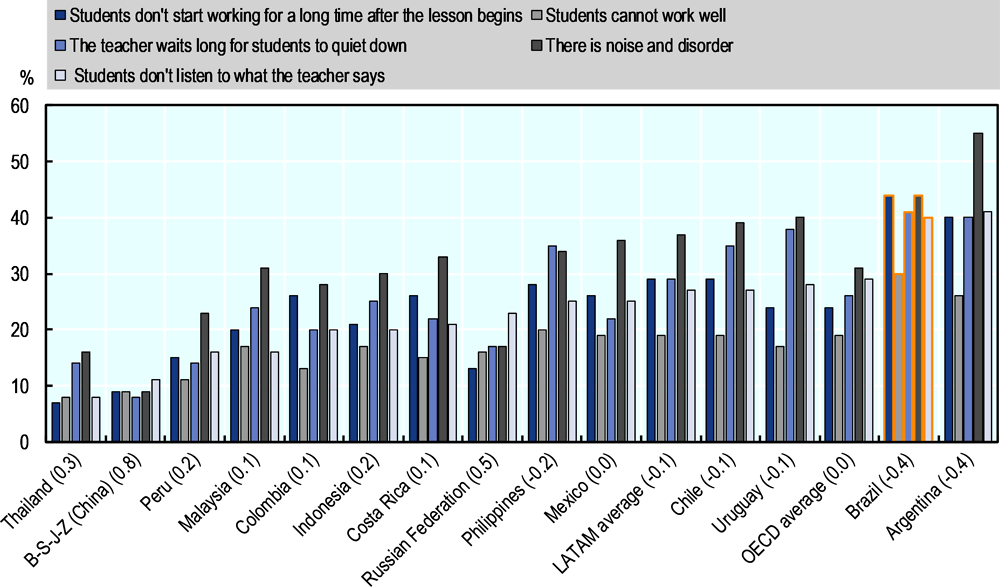

PISA asked students how frequently the following things happen in their language-of-instruction lessons: “Students don’t listen to what the teacher says”; “There is noise and disorder”; “The teacher has to wait a long time for students to quiet down”; “Students cannot work well”; and “Students don’t start working for a long time after the lesson begins” (see Figure 6.2). These statements were combined to create an “index of disciplinary climate”. According to this index, the disciplinary climate is significantly worse in Brazil (index: -0.37) than across OECD countries on average (index: 0.0) and LATAM countries (index: -0.1)1. For example, 44% of students report that students do not start working for a long time after the lesson begins in every or most lessons. This compares to 24% of students in OECD countries, and much lower rates in some East Asian countries and economies such as B-S-J-Z (China) (9%) and Thailand (7%).

A disaggregated analysis shows that students from disadvantaged backgrounds and in public schools in Brazil face slightly worse disciplinary climates (index: -0.39, -0.4 respectively), as measured by PISA’s disciplinary index, which is likely to contribute to their underperformance (see Chapter 3).

As discussed in Chapter 5, disorderly classrooms may explain why Brazilian teachers report spending less of their classroom time on actual teaching and learning (67%) than in OECD countries (78%). This has important implications for students’ learning, as PISA results show that students’ outcomes are significantly higher when there is more conducive classroom dynamics. On average in Brazil, a unit increase in the index of disciplinary climate (equivalent to one standard deviation across OECD countries) was associated with an increase of 12 score points in reading performance (OECD average: 11 score points).

Student-teacher relationships are difficult

Data from PISA and TALIS suggest that student-teacher relationships in Brazil are often strained and sometimes hostile, suggesting that certain Brazilian schools provide an inadequate learning environment for students or teachers. Research shows that this can have enduring consequences for student outcomes, well-being, behaviour, and engagement (OECD, 2015[23]) as well as teacher job satisfaction and retention (see Chapter 5) (Guo and Higgins-D’Alessandro, 2011[24]).

PISA 2018 asked school principals to report the extent to which their school’s capacity to provide instruction was hindered (“not at all”, “very little”, “to some extent” or “a lot”) by students lacking respect for teachers or by teachers being too strict with students. Table 6.1 shows that, on average, school leaders in Brazil are more likely to report that these issues hinder learning than across most benchmark countries. Student’s lack of respect for teachers, in particular, is seen to be an issue.

Bullying

Bullying is prevalent in Brazilian schools

PISA 2018 asked students several questions about their experiences with bullying. On average, nearly a third of students (29%) reported being bullied at least a few times a month (OECD average: 23%) and 12% of students were classified as being frequently bullied (OECD average: 8%). Internationally and in Brazil, PISA 2018 data show that physical bullying was less prevalent than verbal and relational bullying.

National data allow for a more fine-grained picture of school bullying. Results from the National Student Health Survey (Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar, PeNSE) show that among Grade 9 children who report being bullied, most are boys, from ethnic minorities and from modest backgrounds (Oliveira et al., 2015[25]). The 2015 survey also reveals that, according to victims of bullying, the main stated causes for bullying incidents were physical appearance, followed by race/ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and place of origin (IBGE, n.d.[26]). While bullying is often linked to personal issues, the profile of bullying victims seems to reflect Brazil’s socio-economic inequalities, structural racism and other forms of prejudice (see Chapter 1). This warrants careful monitoring and prevention measures from school staff and policymakers.

Bullying has severe physical and emotional long-term consequences for students and is damaging learning outcomes

A wide range of evidence from different countries shows that students who experience bullying as a victim, bully or observer – even if only sporadically – demonstrate lower academic performance. On average, every one-unit increase in the index of exposure to bullying (equivalent to one standard deviation across OECD countries) was associated with a drop of 9 score points in reading, after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile (OECD average: - 9 score points). In Brazil, 15-year-old students who reported being bullied at least a few times a month scored 24 points less in reading than students who were less-frequently bullied, after accounting for students’ and schools’ socio-economic profile (OECD average: -21 score points). The associated drop in scores is even larger when looking at specific types of bullying acts, such as being threatened by other students (Table 6.3).

Moreover, school violence, including bullying, has been shown to damage the mental and physical health of students and leads to many problems including dropout, depression and substance abuse. Teachers also suffer, and it can lead to higher teacher stress levels and absenteeism (Stelko-Pereira and Williams, 2016[27]).

Steps are being taken to fight bullying in Brazil

At the national and sub-national level, steps are being taken to assess and address this issue: self-reported data on bullying is collected by PeNSE and in 2016, the Programme Against Systematic Intimidation was implemented to fight bullying through teacher capacity-building programmes, awareness campaigns and the publication of monitoring reports (Presidência da República, 2015[28]). Education networks are now legally required to have anti-bullying arrangements in place to support students and the overall school community. In the state of Rio Grande do Sul, the Internal Commissions for the Prevention of Accidents and School Violence (Comissões Internas de Prevenção de Acidentes e Violência Escolar, CIPAVEs), formed by students, teachers, members of the school leadership, school staff and families, twice a year assess the level of school violence and identify the challenges faced by the school. The evidence collected is used to develop follow-up measures, some of which are carried out with external partners (Jotz, 2017[29]). Box 6.1 provides some insights from around the world into how anti-bullying programmes work and evidence of their effectiveness.

Many anti-bullying programmes involve a whole-of-school approach, with co-ordinated engagement among teachers, students and parents. Several of these holistic programmes include training for teachers on bullying behaviour and how to handle it, anonymous surveys of students to monitor the prevalence of bullying, and a strategy to provide information to and engage with parents.

The Olweus Bullying Prevention Programme, first developed and implemented in Norway, has greatly influenced the design of anti-bullying strategies around the world. This programme includes meetings among teachers, improved supervision, surveys of students, parent-teacher meetings, role-playing among students to learn how to handle bullies, gathering and disseminating information about bullying for students and parents, developing class rules against bullying, and talking with bullies and their parents without imposing punitive measures. Other prevention programmes include KiVa, which was developed in Finland and is now implemented in Belgium, Estonia, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden, the Kia Kaha programme, developed in New Zealand, and the Respect programme in Norway. Castile and Leon (Spain) recently launched an anti-bullying strategy that co-ordinates plans and actions of all public and private institutions involved in the fight against bullying.

Most evaluations of bullying-prevention programmes find a positive but modest impact. Randomised control trials found that the KiVa programme reduced the incidence of bullying, and also made a positive difference in students’ attitudes toward bullies and victims. Research shows that, of the various possible preventive measures, training and information for parents, better supervision in the playground, improved disciplinary measures, working with peers and classroom management are the most effective. Programmes need to be long-term, and frequently monitored and evaluated to be effective. Those combine systematic monitoring and targeting of high-risk youth are particularly constructive. Although these programmes may not eliminate bullying entirely, interventions make bullying less acceptable to students, teachers, and parents, mitigating the potentially harmful effects.

Source: (OECD, 2019[12]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives, https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en; (Smith, Pepler and Rigby, 2004[30]), Bullying in schools: How successful can interventions be?, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1017/CBO9780511584466 (accessed on 29 June 2020); (Salmivalli, Kärnä and Poskiparta, 2011[31]), Counteracting bullying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied, https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411407457; (Salmivalli, Kaukiainen and Voeten, 2005[32]), Anti-bullying intervention: Implementation and outcome, https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905x26011; (Raskauskas, 2007[33]), Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564 (accessed on 29 June 2020); (Ertesvåg and Vaaland, 2007[34]), Prevention and Reduction of Behavioural Problems in School: An evaluation of the Respect program, https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410701309258; (Evans, Fraser and Cotter, 2014[35]), The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004; (Ttofi and Farrington, 2009[36]), What works in preventing bullying: effective elements of anti‐bullying programmes, https://doi.org/10.1108/17596599200900003; (Ferguson, 2007[37]), The Effectiveness of School-Based Anti-Bullying Programs: A Meta-Analytic Review, https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016807311712; (Nocentini and Menesini, 2016[38]), KiVa Anti-Bullying Program in Italy: Evidence of Effectiveness in a Randomized Control Trial, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0690-z; (Ttofi and Farrington, 2010[39]), Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: a systematic and meta-analytic review, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-010-9109-1.

Sense of belonging

Students report low sense of belonging at school

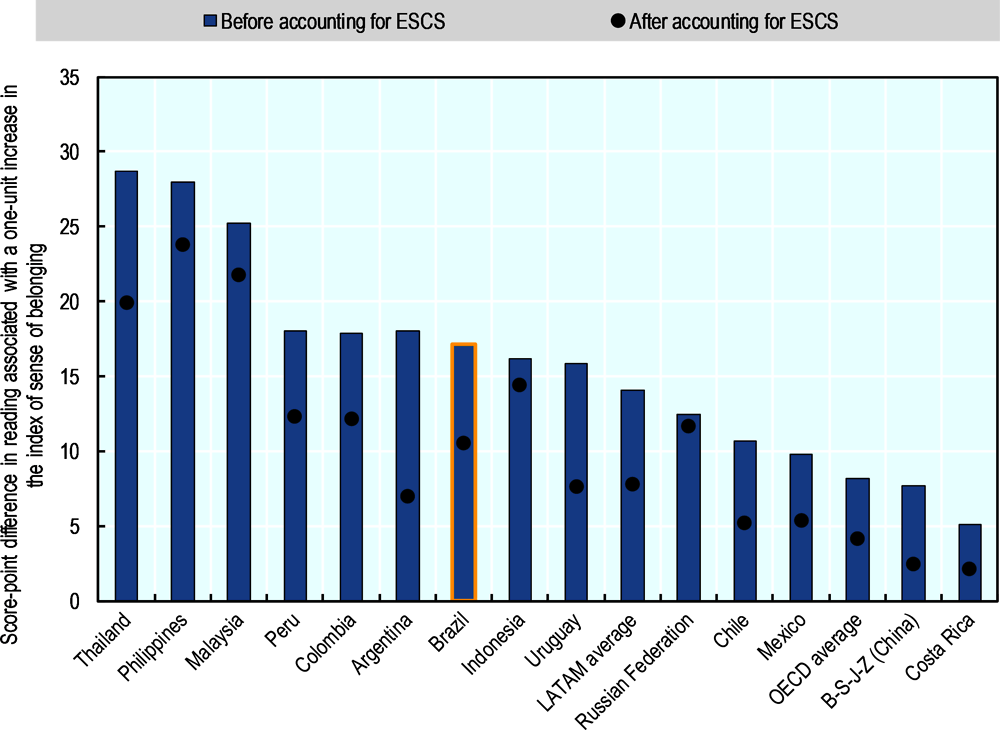

According to PISA evidence, the sense of belonging at school is lower in Brazil (-0.19) than in OECD or LATAM countries (0.0 and -0.09, respectively), on average. This suggests that Brazilian students are less likely to report feeling accepted, respected and/or supported at school. This may reflect some of the factors described above, including undisciplined classroom climate, strained student-teacher relationships and high rates of bullying (Garcia-Reid, 2007[40]; Ma, 2003[41]; OECD, 2017[42]). In Brazil, students in rural (- 0.42) and public schools (-0.24) have less sense of belonging than their peers in urban and private schools (-0.14 and 0.05, respectively).

Supporting students’ engagement with school could support better outcomes

Internationally, and in Brazil, 15-year-old students who reported a stronger sense of belonging at school scored higher in reading, even after accounting for the socio-economic profile of students and schools. On average, a one-unit increase in the index of belonging at school (equivalent to one standard deviation across OECD countries) was associated with an increase of 11 score points in reading, after accounting for the socio-economic profile of students and schools (OECD average: 4 score points) (Figure 6.3). Research shows that students who feel they belong at school are also less likely to engage in risky and anti-social behaviours (Catalano et al., 2004[43]), to play truant and drop out of school (Lee and Burkam, 2003[44]; McWhirter, Garcia and Bines, 2018[45]; Slaten et al., 2015[46]). This suggests that measures targeted at improving school connectedness could help support higher levels of achievement and participation in Brazil (see Box 6.2).

To Be and Belong (Ser e Pertencer) initiative in Rio de Janeiro

The public municipal school E.M. Bernardo de Vasconcellos, offering the last years of elementary education and upper secondary education in the neighbourhood of Penha in Rio de Janeiro, used to be considered one of the worst schools in the area because of poor infrastructure conditions and weak motivation of staff and students. In 2017, new school leadership launched the Ser e Pertencer initiative, which aimed to create an educational environment which would be seen as welcoming, safe, and inclusive by both students and staff. A sports’ court was built through collaboration between school staff, parents and students; and the school was repainted by a local artist, who represented the history of the region and its culture through images on the school walls, alongside motivational statements outlawing discrimination and promoting peace.

The initiative also involved measures designed to encourage more dynamic and inclusive learning: the history teacher used slang and local vocabulary, so students would feel represented and their culture valued. A Walk in Penha (Rolé na Penha) project aimed to stimulate local tourism and students’ knowledge of their region by having students from the neighbourhood present the region, its history and tourist spots to young people from other areas. The project was developed in partnership with a local tourism agency which promotes memory rescue and valorisation of disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods. Other activities included conversation circles and lectures on topics such as mental health, homophobia and religious intolerance.

Source: (Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 2017[47]), Futuro em construção na Vila Cruzeiro [Future under construction in Vila Cruzeiro], http://www.pcrj.rj.gov.br/web/sme/exibeconteudo?id=7317107 (accessed on 20 October 2020); (MultiRio, 2017[48]), Projeto fortalece sentimento de pertencimento dos alunos à E.M. Bernardo de Vasconcellos [Project strengthens students' sense of belonging to E.M. Bernardo de Vasconcellos], http://www.multirio.rj.gov.br/index.php/leia/reportagens-artigos/reportagens/13383-projeto-fortalece-sentimento-de-pertencimento-dos-alunos-%C3%A0-e-m-bernardo-de-vasconcellos (accessed on 20 October 2020).

How students perceive their own learning and potential can influence their attitudes towards learning and school. Students with high expectations for their future careers and strong beliefs in their own capacity for development are more likely to work hard at school and to see value in remaining in education. Conversely disengaged and low-performing students may develop less ambitious aspirations. Students’ expectations and perceptions are also shaped, at the system level, by the structure of the labour market, and the potential returns from education, and at a personal level, by family economic circumstances and wider social expectations and pressures.

Students’ outlook and self-perception

PISA collects data on three important dimensions of students’ self-perception (OECD, 2019[12]):

Self-efficacy: the extent to which students believe in their current ability to engage in certain activities and perform specific tasks, especially when facing adverse circumstances (Bandura A., 1977[49]).

Fear of failure: the extent to which students fear making a mistake because of the perceived negative consequences associated with failing (Lazarus, 1991[50]; Warr, 2000[51]).

Growth mindset: the belief that their ability and intelligence can develop over time (Caniëls M. et al., 2018[52]) (Dweck, 2006[53]).

This section explores how different students perceive themselves and their abilities and the extent to which their perceptions are associated with their performance.

Students’ self-efficacy is associated with stronger outcomes

PISA asked students to report the extent to which they agree (“strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “agree”, “strongly agree”) with the following statements about themselves: “I usually manage one way or another”; “I feel proud that I have accomplished things”; “I feel that I can handle many things at a time”; “My belief in myself gets me through hard times”; and “When I’m in a difficult situation, I can usually find my way out of it”. Brazil’s results are, on average, similar to those across OECD and benchmark countries.

In Brazil, advantaged students are much more likely than their less advantaged peers to report high levels of self-efficacy (index: -0.07 and -0.25, respectively). This matters because greater self-efficacy is associated, in Brazil as well as OECD countries, with stronger reading performance even after accounting for the socio-economic profile of students and schools, and for gender. In Brazil, a one-unit increase in the index of self-efficacy was associated with an increase of five score points in the reading assessment, on average, similar to the association observed in OECD countries (six score points). This is in line with research that suggests that students’ with more positive self-perceptions are more likely to set challenging goals for themselves, persist for longer and expend greater effort (Bandura A., 1977[49]; Ozer and Bandura, 1990[54]).

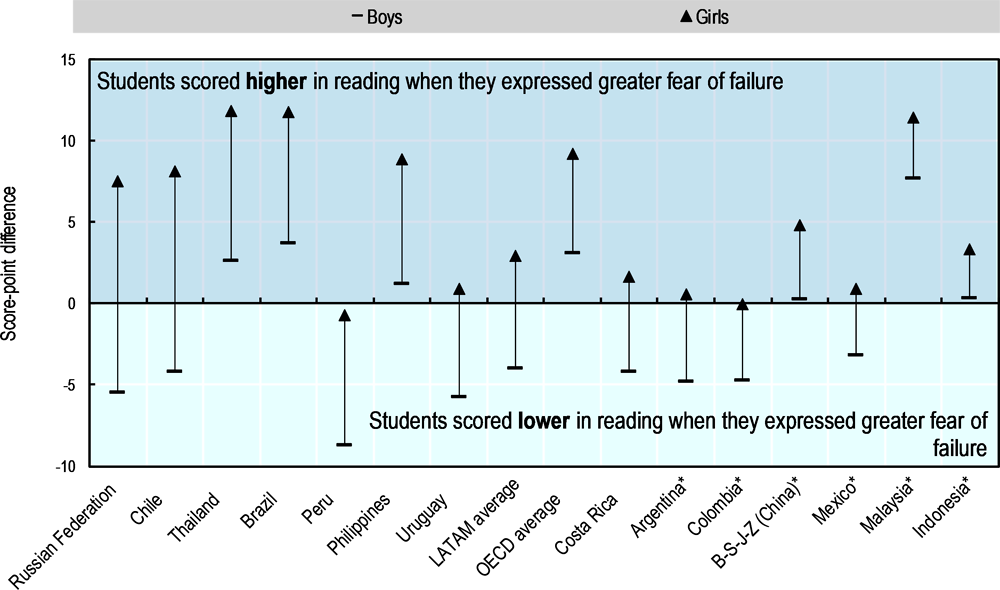

Fear of failure among students is high, especially among girls, but this may encourage stronger performance

Students were asked to report the extent to which they agree (“strongly disagree”; “disagree”; “agree”; “strongly agree”) with the following statements about themselves: “When I am failing, I worry about what others think of me”; “When I am failing, I am afraid that I might not have enough talent”; and “When I am failing, this makes me doubt my plans for the future”. These statements were combined to create the index of fear of failure whose average is zero and standard deviation is one across OECD countries. In Brazil, the fear of failure is 0.04, slightly higher than the average in OECD countries (index: -0.01). Perhaps surprisingly, students who expressed a greater fear of failure scored five points higher in reading than students expressing less concern about failing, after accounting for the socio-economic profile of students, and for gender (OECD average: four score points) (see Figure 6.4).

Disaggregated data show that not only do girls have much higher levels of fear of failure (index: 0.16 for girls and -0.10 for boys), but also that it is a much better predictor of academic performance among girls than among boys (OECD, 2019[12])). In reading, for instance, girls scored 12 points higher for every one-unit increase in the index of fear of failure, after accounting for students’ socio-economic status and the index of self-efficacy, whereas boys scored only 4 points higher.

Overall, Brazil’s results are consistent with international results and evidence that some degree of fear can urge students to expend greater effort on academic tasks. But it needs to be kept within limits: an unreasonable fear of failure has been associated with stress, anxiety, burnout and depression (H, SS and A, 2017[55]; Sagar, Lavallee and Spray, 2007[56]; Conroy, 2001[57]).

“Growth mindset” — a belief that one can improve — is associated with better outcomes

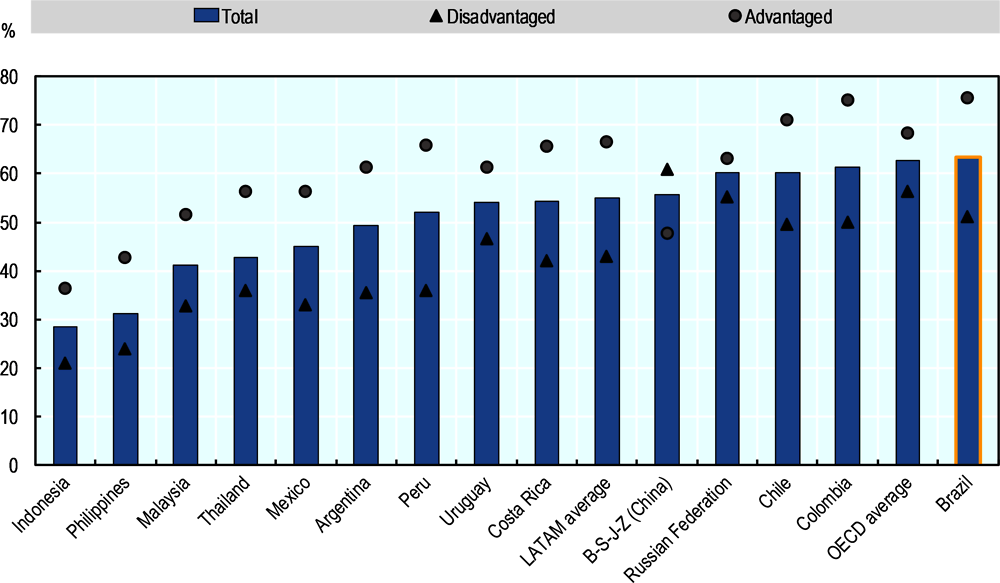

To measure the “growth mindset”, PISA 2018 asked students whether they agreed (“strongly disagree”; “disagree”; “agree”; “strongly agree”) with the following statement: “Your intelligence is something about you that you can’t change very much”. Students who disagreed with the statement are considered to have a stronger growth mindset than students who agreed with the statement. Results for Brazil show that nearly two-thirds of 15-year-olds have a strong growth mindset (63%), which is equivalent to the OECD average and higher than in many LATAM countries (see Figure 6.5).

Internationally, and in Brazil, socio-economically disadvantaged students were more likely than advantaged students to believe that their intelligence cannot change very much over time. However, the gap is much higher in Brazil than in OECD countries: 75% of advantaged students have strong growth mindsets, compared to only 51% of disadvantaged students (OECD average: 68% and 56%, respectively). A similar gap is observed between students in public and private schools.

Internationally, PISA results show a statistically significant positive association between a strong growth mindset and students’ scores. That is to say, students that disagree that “your intelligence is something about you that you can’t change very much” score higher than their peers who agree with the statement. Brazil has one of the strongest associations among PISA-participating countries: students who disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement scored 57 points higher than the latter group after accounting for the socio-economic profile of students and schools (OECD average: 32 score points).

These findings are consistent with the theory that encouraging a growth mindset in students can improve academic performance. However, PISA cannot prove cause and effect: holding a growth mindset could be the result of strong academic performance, rather than the other way around. In the case of Brazil, this discussion is closely linked with socio-economic disparities among students, which may further reinforce performance gaps.

Academic expectations

Great expectations: most students aspire to enter university

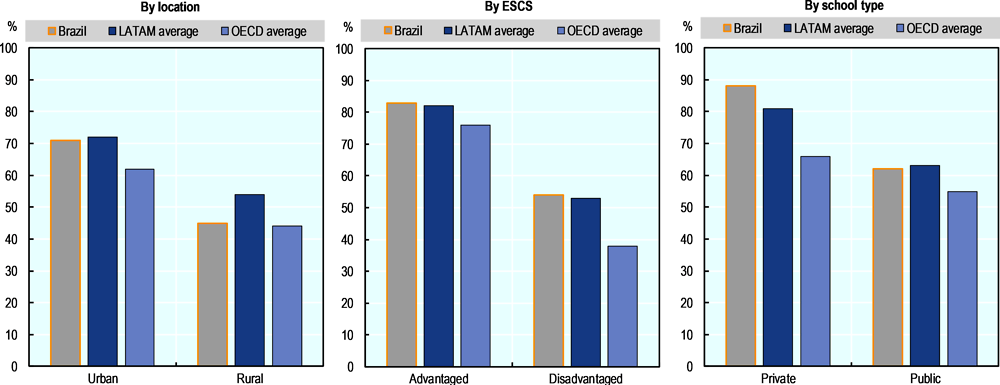

In Brazil, 66% of 15-year-olds report that they expect to obtain a tertiary qualification (ISCED 5 or more). While similar to Latin American countries (67%), this share is higher than the one found in OECD countries (56%) on average (Figure 6.6). As is the case elsewhere, in Brazil, students from more advantaged backgrounds, private schools or urban areas are more likely to expect to progress into higher levels of education.

Such expectations might reflect socio-economic circumstances and the broader education structure

Expectations of entry to higher education are likely a reflection of wider societal and family pressures. PISA 2018 results show that 73% of Brazilian parents expect their children to complete a tertiary degree, which compares to 63% in OECD countries. These high aspirations are striking, as participation in tertiary education is in fact much lower in Brazil than in OECD countries (see Chapter 2). As discussed in Chapter 3, there are very good labour market returns to tertiary qualifications in Brazil, providing strong economic incentives for young Brazilians to aim for university.

These strong aspirations for tertiary level education among 15-year-olds suggest that secondary education in Brazil may be seen by students primarily as an academic path to university, with few opportunities for children to acquire more practical knowledge and skills. This has implications for adolescents and young adults, as well as for the Brazilian labour market (OECD, 2018[59]; OECD, 2020[60]). The recent restructuring of upper secondary education in Brazil is a chance to address this issue, as students will be able to take more vocational and technical courses as part of their studies. It might also offer the possibility of strengthening one- or two-year postsecondary vocational programmes (at ISCED 4 and 5) that might meet the need for higher technical skills in the Brazilian economy. This level of education is currently relatively undeveloped in Brazil compared to many OECD and other countries. It would also help address the current wide gap, identified above, between high academic aspirations among 15-year-olds, and relatively low levels of participation in higher education programmes (at ISCED 6 level).

Student well-being, defined as the quality of students’ lives, has increasingly been identified as important by policy makers and educators around the world. Evidence shows that students who feel that they are part of a community and supported by others, tend to have stronger motivation and better academic performance. Higher well-being also has wider benefits, including a link to better health and less anti-social behaviour (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005[61]; Park N., 2004[62]).

In Brazil, as in other countries, increasing attention is being given to how the education system can support student well-being. Since the early 2000s, federal and local initiatives have promoted healthy lifestyles in schools and sought to prevent violence. In recent years, PeNSE has collected data on student well-being and the school environment (see Box 6.6). But gaps remain in the policy measures. First, some key dimensions of well-being, especially psychological health, tend to be overlooked, and little data collected. This makes it difficult to assess the existing (and emerging) issues, monitor the effectiveness of on-going programmes and develop targeted responses. Second, without a common framework for student well-being, there has been limited continuity or alignment in policies at the national and sub-national levels.

In 2020, COVID-19 has had a new, damaging and unanticipated impact on student well-being. School closures and lockdowns inhibited social life, and sometimes damaged nutrition because of the loss of access to school meals. International evidence suggests that in times of crisis and lockdowns, children may be more at risk of maltreatment, neglect, sexual abuse and teenage pregnancies (Folha de S. Paulo, 2020[63]; OECD, 2020[64]). While most schools are now (in late 2020) re-opening, even if only part-time, the COVID-19 health and economic crisis will have long-lasting effects on students’ well-being and life chances. This crisis has also exposed the lack of any systematic and co-ordinated approach to student well-being in Brazil.

This section will draw on PISA (see Box 6.4 for PISA’s definition of well-being), and national results looking at four different dimensions: their material, psychological, physical and social well-being. The data were collected before the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore do not reflect students’ well-being during and after school closures and the crisis.

The five domains of student well-being identified in the Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-Being in the PISA 2015 Study are:

Cognitive well-being, which refers to the knowledge and skills students have to participate effectively in today’s society, as lifelong learners, effective workers and engaged citizens. This is discussed in Chapter 3.

Material well-being, which refers to the material resources that make it possible for families to provide for their children’s needs, and for schools to support students’ learning and healthy development.

Psychological well-being, which includes students’ evaluations and views about their lives and their feelings and issues.

Physical well-being, which refers to students’ health status, engagement in physical exercise and the adoption of healthy eating habits. Limited data for Brazil meant that sources other than PISA had to be explored.

Social well-being, which refers to the quality of social lives. For the purposes of this report, the analysis will distinguish between students’ social life at school (with peers and friends) and their connections within the home environment (with parents and families).

Source: (Borgonovi and Pál, 2016[65]), "A Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-Being in the PISA 2015 Study: Being 15 In 2015", https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlpszwghvvb-en.

Material well-being

PISA student questionnaires are used to compute the PISA Index of Economic, Social and Cultural Status (ESCS), which is a composite score based on parental education, highest parental occupation and home possessions, which acts as a proxy for wealth. Analysis of the students’ home possessions indicator offers insights into the material well-being of Brazilian students and their access to educational resources. This is particularly important in the context of an economic and health crisis which may exacerbate inequalities in Brazil.

Brazilian students are not as wealthy as their OECD peers, and there are large disparities

According to PISA 2018 results, on average, Brazilian students’ index of home possessions (-1.43) is significantly lower than that found across OECD countries (-0.04) although similar to Latin American comparison countries (-1.27) with the exception of Chile (-0.71) and Uruguay (-0.96) (Table 6.5). Moreover, the disparities between students in rural and urban schools, public and private schools, and from disadvantaged and advantaged backgrounds are much wider than those found in OECD countries, although similar to those in LATAM countries on average. The same is observed across all indices.

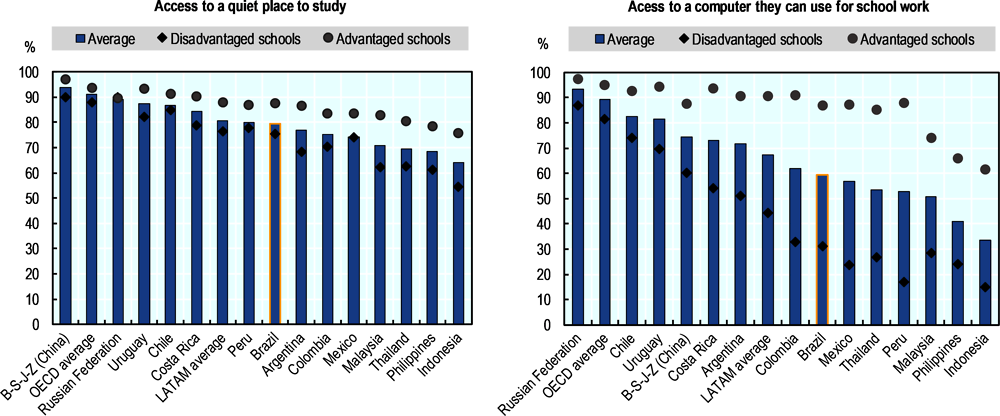

Lack of access to basic educational resources at home can be a barrier for learning, in particular for disadvantaged students

PISA research shows that home education resources, including quiet study space and Internet access, are associated with stronger learning outcomes (OECD, 2017[42]). Although less than 10% of Brazilian 15-year-olds have no home Internet access, (OECD average: 4%) (OECD, 2020[66]), 20% of students have no quiet place to study (OECD average: 9%) and 40% have no computer that they can use for school work (OECD average: 11%) (see Figure 6.7). Access to home educational resources is closely tied to socio-economic background everywhere, but the disparities are much wider in Brazil than in most OECD countries. For example, 31% of students from disadvantaged schools have a computer to work with at home, compared to 89% of advantaged students. This compares to a 14 percentage point difference in OECD countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly increased the importance of home Internet access and computing facilities, as distance learning and socially-distanced school models (e.g. hybrid classrooms) become the norm. Students lacking these facilities at home (most disadvantaged students), risk falling further behind in their studies (see Chapter 3). While certain initiatives have been taken at the local or school level to support these students (e.g. laptop donations or using social media tools), many students remain unable to follow their online courses.

Psychological well-being

Psychological well-being is a vital element in health (Choi, 2018[67])(Box 6.4), a key component of overall well-being (Pollard and Lee, 2003[68]) and a precondition of "good quality" life (Morgan et al., 2007[69]). Childhood and adolescence are crucial periods in the development of psychological well-being. Children who are in a good state of emotional well-being have a much better chance of growing into adults who are happy, confident and able to enjoy healthy lifestyles, and to contribute to society (Morgan et al., 2007[69]; OECD, 2015[70]). Conversely, adult mental health disorders mostly originate during childhood or adolescence (Kessler et al., 2007[71]; Paus, Keshavan and Giedd, 2008[72]; Kieling et al., 2011[73]; Jones, 2013[74]), but treatment usually does not begin until later in life due to the stigma and lack of awareness, as well as other cultural or social norms. Nearly one-in-two adult mental health problems begin by age 14 and 75% by the mid-20s (WHO, 2020[75]) and many of these problems recur and persist.

Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, PISA results revealed worrying evidence related to declining levels of students’ life satisfaction in Brazil. More recently, national surveys have revealed the damaging impact of school closures and lockdown measures, with between 40% and 50% of interviewees reporting sadness, irritation and lack of motivation as a result of the disruption (Fundação Lemann, 2020[76]). At the same time, the pandemic has disrupted child and adolescent mental health services and identification, partly because of social distancing measures and partly because of the redeployment of staff to COVID-19 activities (Chevance et al., 2020[77]). School closures also interrupt the use of schools as a common site for mental health interventions, especially for low-threshold interventions (McDaid, Hewlett and Park, 2017[78]).

Although the terms “psychological well-being”, “emotional well-being” and “mental health” are often used as synonyms, there are some important differences:

Mental health is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community." It is commonly used as a clinical indicator for the existence or absence of mental disorders and diseases.

Emotional well-being – often referred to as "hedonic well-being" – has been defined as “the quality of an individual's emotions and experiences, i.e. sadness, anxiety, worry, happiness, stress depression, anger, joy, and affection that leads to unpleasant or pleasant feelings”. Emotional well-being encompasses mental health.

Psychological well-being, as defined by PISA’s Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-being, depends on students’ evaluations and views about their lives, their engagement with school, and the goals and ambitions they have for their future. Psychological well-being encompasses aspects both of emotional well-being and mental health. However, in PISA, no direct objective indicators for well-being as a whole are available. This means that the PISA data cannot be used to make conclusions about students’ mental health.

Source: (OECD, 2019[79]), PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework, https://doi.org/10.1787/b25efab8-en; (Choi, 2018[67]), Emotional well-being of children and adolescents: Recent trends and relevant factors, https://doi.org/10.1787/41576fb2-en.

Life satisfaction among Brazilian students is similar to the OECD average but lower than in neighbouring countries

PISA 2018 defines life satisfaction in terms of an individual’s evaluation of their quality of life (Shin and Johnson, 1978[80]). Box 6.5 explains how the assessment measured students’ satisfaction. Brazilian students reported 7.1 on the life satisfaction scale, similar to the OECD average (7.0), but slightly lower than the LATAM average (7.5). On average across OECD countries, and in Brazil, PISA data show that boys are more likely than girls to be “satisfied” with their lives (the gender gap is equivalent to 11 percentage points in Brazil and in OECD countries). While in most countries, students from more advantaged backgrounds are more likely to be satisfied with their lives, this was not the case for Brazil.

PISA 2018 asked students to rate their life satisfaction on a scale from 0 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied). Based on students’ responses, 15-year-olds were classified into four different groups and are referred to as the following:

A student is “not satisfied” if he or she reported between 0 and 4 on the life-satisfaction scale

A student is “somewhat satisfied” if he or she reported 5 or 6 on the life-satisfaction scale

A student is “moderately satisfied” if he or she reported 7 or 8 on the life-satisfaction scale

A student is “very satisfied” if he or she reported 9 or 10 on the life-satisfaction scale

A fifth group “satisfied” combines the two groups of students that reported the highest levels of life satisfaction (between 7 and 10 on the life-satisfaction scale).

Source: (OECD, 2019[12]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives, https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en.

PISA 2015 asked the same question about life satisfaction as PISA 2018. In Brazil, as in most participating countries, students reported less satisfaction with their lives in 2018 than they did in 20152, with a larger decline in Brazil (-0.53) than in OECD countries (-0.30). While it is important not to infer much from only two data points, this decline should be monitored.

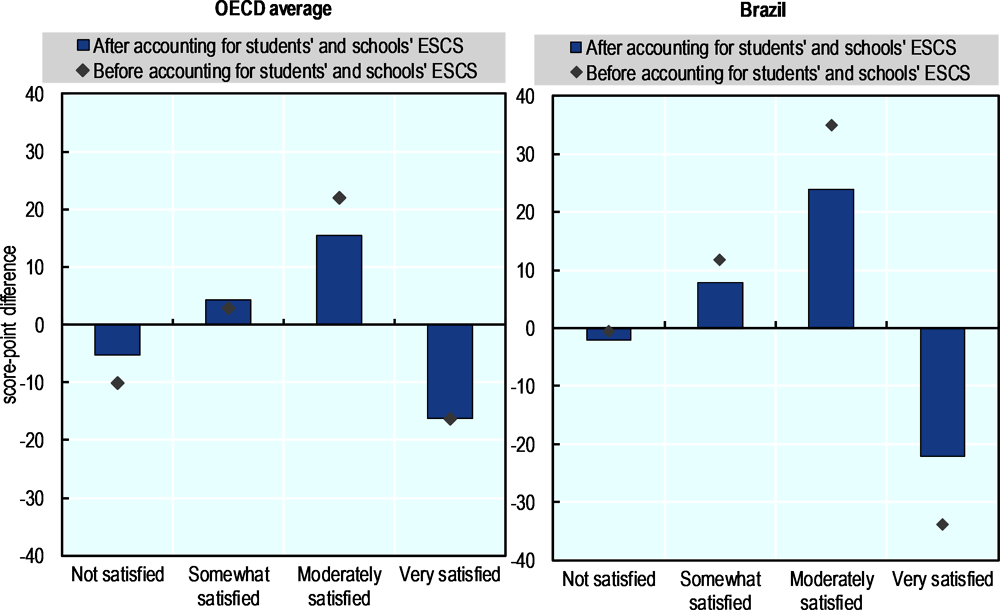

Higher life satisfaction does not always mean better outcomes

In Brazil and in OECD countries, PISA 2018 results show an inverted U-shaped relationship between reading performance and life satisfaction. Reading scores were lower amongst students who reported between 0 and 4, and 9 or 10 on the life-satisfaction scale, while reading scores were higher among students who reported 5 through 8 on the scale (see Figure 6.8).

Students’ feelings can support better outcomes only to a certain point

PISA asked students to report how frequently (“never”; “rarely”; “sometimes”; “always”) they feel happy, lively, proud, joyful, cheerful, scared, miserable, afraid and sad. Overall, Brazilian students reported feeling good about their lives. Between 80% and 90% of students reported sometimes or always feeling happy, cheerful, joyful and lively; 65% reported feeling proud with the same frequency. By contrast, around 40% of students sometimes or always feel scared, sad and miserable, and about half of students reported feeling afraid with the same frequency. These results are relatively similar to those found in OECD and LATAM countries (OECD, 2019[12]). Negative feelings, as long as they do not dominate lives, are not necessarily harmful, as they can play a constructive role in life. The relationships between students’ feelings and reading performance are curvilinear (increasingly positive until a certain point and decreasing thereafter), similar to the pattern for life satisfaction.

Physical well-being

In OECD and partner countries, as in Brazil, many children and young people are risking their health through lack of exercise, poor diet and insufficient sleep (Aston R., 2018[81]). This reflects wider trends, including but not limited to, the use of technology, changing family structures and sedentary lives. At the same time, there is growing awareness of the impact of physical health on cognitive, mental and social well-being (and vice versa), and how negative impacts can reduce academic performance and increase social costs. As a result, educators and policymakers are increasingly interested in the role education and schools might play in addressing physical health issues.

This section looks at self-reported data from PISA 2015 student questionnaires3, and from PeNSE (see Box 6.6). This offers an indication – albeit imperfect and incomplete – of 15-year-old students’ health conditions, and the extent to which they engage in healthy habits.

PeNSE is a survey carried out by the national Brazilian government in a collaboration between the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, IBGE), the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education (Ministério da Educação, MEC) since 2009. As a sample survey, PeNSE collects self-reported information from students from both public and private sectors with the goal of identifying and monitoring behavioural risk factors and health protection of young students in Brazilian schools.

Since its first cycle, PeNSE’s questionnaire has evolved and together with the improvement of data collection instruments (see below), these developments have allowed the survey to cover a wide array of topics and collect more disaggregated data, including:

the four common risk factors for chronic non-communicable diseases (smoking, physical inactivity, inadequate nutrition and alcohol consumption)

the following themes: socio-economic aspects of students, including family context; drug use and consumption; sexual and reproductive health; eating habits; hygiene habits; mental health; violence, safety and accidents; perception of body image; student well-being

information about characteristics of the school environment.

Initially, PeNSE’s target population were students from Grade 9. Since 2015, the survey has collected data from two different sampling groups: students attending Grade 9, as before, allowing for trend comparability, and 13-17 year-olds, i.e. students attending Grades 6-9 of elementary education and Grades 1-3 of upper secondary education. This second sample allows for a stronger developmental focus, and better comparability with the international Global School-Based Student Health Survey (GSHS), developed by the WHO.

For PeNSE’s most recent, 2019 edition, a single national sample of 13-17 year-old students from public and private schools will be used to guarantee international comparability with GSHS. PeNSE has no fixed periodicity. Since 2012, the survey results have been available at the national and region level. In 2015, results were available by states and state capitals (for sample 1).

Source: (Ministério da Saúde, 2020[82]), Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar (PeNSE): o que é, para que serve, temas [National Student Health Survey (PeNSE): what is it, what is it for, themes], http://antigo.saude.gov.br/saude-de-a-z/pense (accessed on 13 October 2020); (IBGE, n.d.[83]), Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar - PeNSE [National Student Health Survey - PeNSE], https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9134-pesquisa-nacional-de-saude-do-escolar.html?=&t=o-que-e (accessed on 13 October 2020).

Obesity rates are high

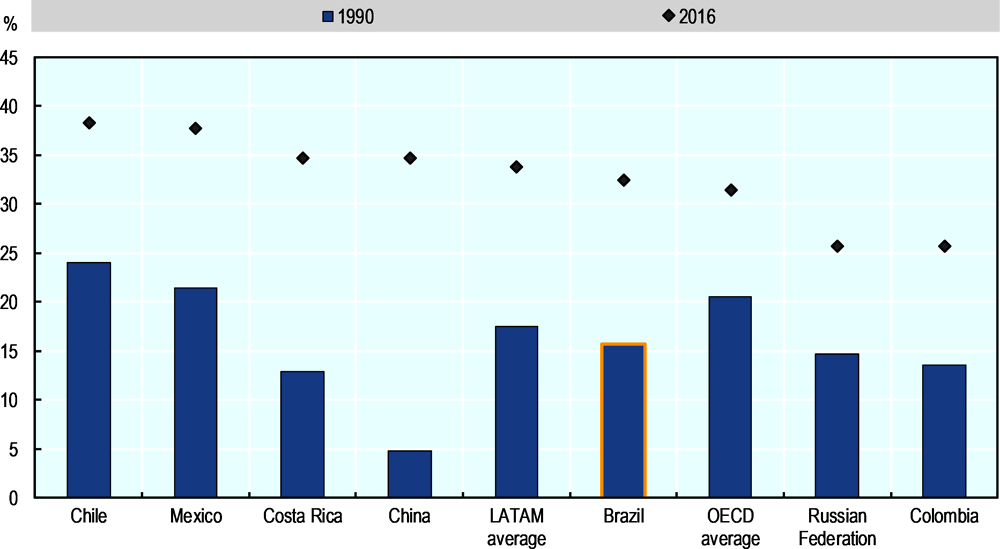

In 2017, a third of Brazilian children (5-9 year-olds) were overweight, similar to the OECD average (31%) but better than Costa Rica (35%), Mexico (38%) and Chile (38%). However, this share has doubled since 1990 (16%) (see Figure 6.9) (OECD, 2019[84]). Childhood obesity is a strong predictor of obesity in adulthood, which is in turn linked to diabetes, heart disease and certain types of cancer (Bösch, 2018[85]; OECD, 2019[84]). Obesity can also lead to poor self-esteem, eating disorders and depression. It may also inhibit participation in educational and recreational activities

Childhood obesity is a complex issue with many causes. In Brazil, the response has been to implement a suite of complementary policies involving government, community leaders, schools, health professionals and industry. The Health in Schools Programme (Programa Saúde nas Escolas, PSE), undertaken by the Ministry of Education, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and municipalities aims to assess and monitor students’ health, and encourage healthy habits, including a balanced diet and physical activity (Presidência da República, Casa Civil, 2007[86]).

Brazilian students are not very physically active at school or during their free time

Self-reported data suggest that in 2015, only 20% of lower secondary Brazilian children reach the recommended 300 minutes a week of moderate or vigorous activity (Saúde Brasil, Governo Federal, 2017[87]). PISA 2015 also reveals that one in fine Brazilian students failed to engage in any moderate or vigorous physical activity during the week, nearly twice the OECD average (see Table 6.6).

Schools play an important role in encouraging and offering physical exercise, through physical education (PE) lessons or extra-curricular activities. While physical education is compulsory in Brazil’s basic education, more than one in ten students (14%) reported not having had any PE classes in the week prior to the PeNSE 2015 survey. Several factors may explain low participation. First, many schools, and in particular municipal schools at the primary and lower secondary levels, lack the necessary infrastructure (e.g. football field) (INEP, 2020[88]). Second, schools are still seen, for the most part, as places where students acquire academic skills and, as a result, students’ physical health and development are much less valued than other classes (e.g. mathematics). Third, many students are unable to take part in physical activities outside of school, either because of lack of safe spaces and activity offerings outside of school, or because of lack of time due to care and work responsibilities. Currently, the need to impose social distancing measures and potential school closures may further discourage physical activity in and outside schools.

Social well-being

An extensive research literature has documented the importance of families for children's cognitive, developmental, educational, labour and health outcomes (OECD, 2011[89]). Outside families, other peers can also affect these outcomes, both positively and negatively (Haynie and Osgood, 2005[90]; Reitz et al., 2014[91]; Hay, 2005[92]; Burns and Gottschalk, 2019[2]). Problems with home and family relationships can have profoundly negative effects on well-being (Stavropoulos et al., 2015[93]). Peer rejection and feeling disliked by your peers have been shown to be a strong predictor of having difficulties in school, such as truancy, dropout and disciplinary problems (Hartup, 1992[94]). For example, poor parental contact and poor peer relationships (i.e. not being happy with classmates, spending time alone) are significant predictors of adult mental and functional health (Landstedt, Hammarström and Winefield, 2015[95]). These are important factors in Brazil, as student truancy, dropout and disciplinary problems are common.

Students report that their social connections in school are not always positive

Self-reported data collected through PISA 2018 questionnaires suggests that, for the most part, Brazilian youth benefit from healthy social lives: 70% of 15-year-olds agree or strongly agree that they make friends easily at school, and 78% agree or strongly agree that other students seem to like them. These are similar to results from OECD and LATAM countries (OECD, 2019[12]).

But some indicators for Brazil are more concerning. Bullying is common, and less than half of Brazilian students report that students value co-operation or cooperate with each other (48% for both), a lower figure than in OECD countries on average (57% and 62%, respectively) (OECD, 2019[12]). Around one-quarter of PISA-participating students report feeling lonely at school (23%). Such loneliness is particularly worrying in the context of school closures due to COVID-19. International organisations have warned that millions of children are currently missing social contact that is essential to learning and development (UNESCO, n.d.[96]).

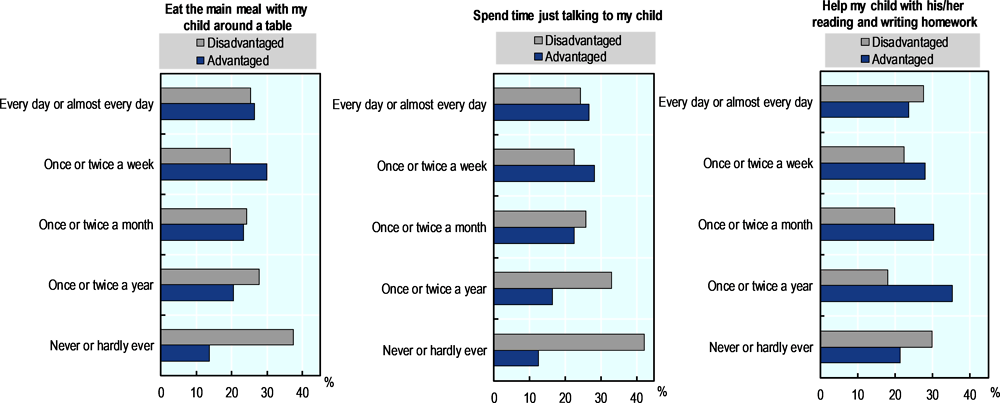

The home environment: differences in parental support may further increase disparities

Even as children mature, family support remains critical. PISA 2018 collected self-reported data from students on the type and frequency of parental emotional and learning support. In every education system, emotional support from parents, as perceived by students, was positively associated with students’ positive feelings. Compared with OECD countries for which there is available data, Brazilian students receive less emotional and learning support from their parents. Brazilian parents are more likely to spend time with their children talking (85%) or having a meal (84%), but are rather less likely to spend time helping them with school work (41%) (OECD, 2019[12])4.

Students from disadvantaged backgrounds are much less likely to report feeling supported (see Figure 6.10). Parents with low levels of educational attainment often struggle to communicate with school staff, and to support their children with academic tasks and questions. Many also lack the time to be involved in their children’s schoolwork. Others are simply unaware of the importance of doing so. Differences in emotional support may therefore be contributing to the observed performance disparities between advantaged and disadvantaged students (Chapter 3).

This chapter highlights four main issues that children and adolescents in Brazil face, which not only contribute to their underperformance in education, but also negatively impact their well-being. These are:

First, the Brazilian school climate is not very conducive to learning or students’ well-being. Student misbehaviour and disruption in the classroom is common and takes time away from actual learning. Furthermore, relationships among students and between students and teachers in schools are strained and, at times, hostile. This creates an unsafe environment where students feel little connection, which in combination with a disengaging curricula, encourages student truancy, dropout and underperformance. Evidence suggests this issue is particularly prominent in public and disadvantaged schools.

Second, students perceive few attractive options for their future academic and professional careers, other than a university degree. The fact that Brazilian students aspire to obtain a university degree is understandable considering the large economic benefits associated with tertiary attainment (see Chapter 3). However, the fact that this is the expectation of the majority of 15-year-olds despite the fact that few actually attain a tertiary qualification is concerning. First, this suggests that secondary education is narrowly understood as a pathway to university and, in turn, to the labour market. As a result, few young Brazilians perceive – much less aspire to – any other alternative for their future. The effect is that the very large proportion of Brazilians who aspire to university entrance but fail to achieve it may, as a result, become disillusioned and unmotivated. This is particularly concerning because, at present in Brazil, young adults have few opportunities to pursue alternative vocational and professional pathways.

Third, not enough is being done to promote children’s well-being. There is growing recognition in Brazil that education is not only a narrow academic enterprise, but also a means for individuals to develop key social and emotional skills that allow them to become independent citizens, build social connections and help attain a sense of control over – and satisfaction with – their life and future. Despite this recognition, many aspects of psychological, social and physical health remain overlooked. Too many students are overweight or obese, and too few take sufficient exercise. The COVID-19 crisis has magnified many of these challenges and therefore the importance of supporting children’s well-being.

Fourth, parental and home environments are not always able to support their children’s education. Disadvantaged families are particularly likely to lack the cultural and economic resources to offer their children sufficient support at school. This may contribute to inequity in learning outcomes, particularly if the home resource gap is not effectively compensated in the school environment. Once again, the COVID-19 crisis and the move to distance learning has amplified this issue, as home support becomes doubly vital during school closures. As schools reopen, it will be vital for schools to reach out to those who have fallen furthest behind and help them succeed despite the multiple challenges they have faced.

References

[18] ABGLT (2016), Pesquisa Nacional sobre o Ambiente Educacional no Brasil 2015: as experiências de adolescentes e jovens lésbicas, gays, bissexuais, travestis e transexuais em nossos ambientes educacionais, Associação Brasileira de Lésbicas, Gays, Bissexuais, Travestis e Transexuais. Secretaria de Educação, Curitiba, https://abglt.org.br/pesquisa-nacional-sobre-o-ambiente-educacional-no-brasil-2016/ (accessed on 19 October 2020).

[81] Aston R. (2018), “Physical health and well-being in children and youth: Review of the literature”, OECD Education Working Papers, N° 170, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/102456c7-en.

[19] Aucejo, E. and T. Romano (2016), “Assessing the effect of school days and absences on test score performance”, Economics of Education Review, Vol. 55, pp. 70-87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.08.007.

[49] Bandura A. (1977), “Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change”, Psychological Review, Vol. Vol. 84/(2), pp. pp. 191-215, https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4.

[65] Borgonovi, F. and J. Pál (2016), “A Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-Being in the PISA 2015 Study: Being 15 In 2015”, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jlpszwghvvb-en.

[85] Bösch, S. (2018), Taking Action on Childhood Obesity, World Health Organization & World Obesity Federation, Geneva, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/274792/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-18.1-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[2] Burns, T. and F. Gottschalk (2019), Educating 21st Century Children: Emotional Well-being in the Digital Age, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b7f33425-en.

[52] Caniëls M. et al. (2018), “Mind the mindset! The interaction of proactive personality, transformational leadership”, Career Development International, Vol. Vol. 23/(1), pp. pp. 48-66, https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2016-0194.

[43] Catalano, R. et al. (2004), “The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: findings from the Social Development Research Group”, The Journal of school health, pp. 252-261, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x.

[77] Chevance, A. et al. (2020), “ssurer les soins aux patients souffrant de troubles psychiques en France pendant l’épidémie à SARS-CoV-2 [Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: A narrative review]”, L’Encephale, Vol. 46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2020.03.001.

[67] Choi, A. (2018), “Emotional well-being of children and adolescents: Recent trends and relevant factors”, OECD Education Working Papers 169, https://doi.org/10.1787/41576fb2-en.

[57] Conroy, D. (2001), “Fear of Failure: An Exemplar for Social Development Research in Sport”, Quest, Vol. 53/2, pp. 165-183, https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2001.10491736.

[4] de Assis, S. et al. (2007), Ansiedade em Crianças: Um olhar sobre transtornos de ansiedade e violências na infância [Anxiety in children: a look at anxiety disorders and childhood violence], FIOCRUZ/ENSP/CLAVES/CNPq, Rio de Janeiro, http://www5.ensp.fiocruz.br/biblioteca/dados/txt_530050460.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2020).

[1] de Barros, R. and R. Medonça (2010), Trabalho infantil no Brasil: rumo à erradicação [Child labor in Brazil: towards eradication], Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada, Brasília, https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/images/stories/PDFs/TDs/td_1506.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2020).

[53] Dweck, C. (2006), Mindset, Random House, New York, NY.

[10] Engeström, Y (2009), “From learning environments and implementation to activity systems and expansive learning”, Actio: An International Journal of Human Activity Theory, Vol. Vol. 2, pp. pp. 17-33.

[34] Ertesvåg, S. and G. Vaaland (2007), “Prevention and Reduction of Behavioural Problems in School: An evaluation of the Respect program”, Educational Psychology, pp. 713-736, https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410701309258.

[35] Evans, C., M. Fraser and K. Cotter (2014), “The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review”, Aggression and Violent Behavior, Vol. 19/5, pp. 532-544, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004.

[13] Exame (2010), MEC diz que 18% deixam escola por falta de interesse [MEC says 18% leave school for lack of interest], https://exame.com/economia/http-www-abril-com-br-noticias-brasil-mec-diz-18-deixam-escola-falta-interesse-1054376-shtml-560094/ (accessed on 8 October 2020).

[37] Ferguson, C. (2007), “The Effectiveness of School-Based Anti-Bullying Programs: A Meta-Analytic Review”, Criminal Justice Review, pp. 401–414, https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016807311712.

[63] Folha de S. Paulo (2020), Pesquisa aponta aumento de ansiedade e tristeza em jovens na pandemia [Research points to increased anxiety and sadness in young people during the pandemic], https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2020/08/pesquisa-aponta-aumento-de-ansiedade-e-tristeza-em-jovens-na-pandemia.shtml (accessed on 11 October 2020).

[5] Fraser (2015), “Classroom learning environments”, Encyclopedia of Science Education, Springer, Netherlands, pp. pp. 154-157.

[76] Fundação Lemann (2020), Educação não presencial na perspectiva dos alunos e famílias [Non-presential education from the perspective of students and families], https://fundacaolemann.org.br/materiais/educacao-nao-presencial-na-perspectiva-dos-alunos-e-familias-453 (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[40] Garcia-Reid, P. (2007), “Examining Social Capital as a Mechanism for Improving School Engagement Among Low Income Hispanic Girls”, Youth & Society, Vol. 39/2, pp. 164-181, https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118x07303263.

[6] Gislason (2010), “Architectural design and the learning environment: A framework for school design research”, Learning Environments Research, Springer, Netherlands, pp. pp. 127-145, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-010-9071-x.

[24] Guo, P. and A. Higgins-D’Alessandro (2011), The place of teachers’ views of teaching in promoting positive school culture and student prosocial and academic outcomes, Paper presented at the Association for Moral Education annual conference, Nanjing, China.

[20] Hallfors, D. et al. (2002), “Truancy, Grade Point Average, and Sexual Activity: A Meta-Analysis of Risk Indicators for Youth Substance Use”, Journal of School Health, Vol. 72/5, pp. 205-211, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06548.x.

[92] Hay, D. (2005), Early Peer Relations and their Impact on Children’s Development, Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/peer-relations/according-experts/early-peer-relations-and-their-impact-childrens-development#:~:text=The%20risk%20for%20children%20with,children%20against%20later%20psychological%20problems. (accessed on 19 October 2020).

[90] Haynie, D. and D. Osgood (2005), “Reconsidering Peers and Delinquency: How do Peers Matter?”, Social Forces, pp. 1109–1130, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1353/sof.2006.0018.

[55] H, G., S. SS and S. A (2017), “Fear of failure, psychological stress, and burnout among adolescent athletes competing in high level sport”, Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, pp. 2091-2102, https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12797.

[17] Hutzell, K. and A. Payne (2012), “The Impact of Bullying Victimization on School Avoidance”, Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, Vol. 10/4, pp. 370-385, https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204012438926.

[26] IBGE (n.d.), Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar - PeNSE (2015) [[National Student Health Survey - PeNSE (2015)], https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/saude/9134-pesquisa-nacional-de-saude-do-escolar.html?edicao=17050&t=downloads (accessed on 9 October 2020).

[83] IBGE (n.d.), Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar - PeNSE [National Student Health Survey - PeNSE], https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9134-pesquisa-nacional-de-saude-do-escolar.html?=&t=o-que-e (accessed on 13 October 2020).

[88] INEP (2020), Censo da Educação Básica 2019: Resumo Técnico [Census of Basic Education 2019: Technical Summary], Instituto Nacional de Estudos e Pesquisas Educacionais Anísio Teixeira, Brasília, http://portal.inep.gov.br/documents/186968/484154/RESUMO+T%C3%89CNICO+-+CENSO+DA+EDUCA%C3%87%C3%83O+B%C3%81SICA+2019/586c8b06-7d83-4d69-9e1c-9487c9f29052?version=1.0 (accessed on 19 October 2020).

[74] Jones, P. (2013), “Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset”, The British journal of psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164.

[29] Jotz, M. (2017), O combate a antimidação sistemática sob a tutela da constituição federal: “bullying” é questão de direito [The fight against systematic antimidation under the tutelage of the federal constitution: “bullying” is a matter of right], Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, https://www.pucrs.br/direito/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2017/03/maria_jotz_2016_2.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2020).

[71] Kessler, R. et al. (2007), “Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature”, Current opinion in psychiatry, Vol. 20, pp. 359–364, https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c.

[73] Kieling, C. et al. (2011), “Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action”, The Lancet, Vol. 378/9801, pp. 1515-1525, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1.

[22] Kimberly, H. and D. Huizinga (2007), “Truancy’s Effect on the Onset of Drug Use among Urban Adolescents Placed at Risk”, Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 40/4, pp. 358.e9-358.e17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.138.

[95] Landstedt, E., A. Hammarström and H. Winefield (2015), “How well do parental and peer relationships in adolescence predict health in adulthood?”, Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, pp. 460-468, https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1403494815576360.

[50] Lazarus, R. (1991), “Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion”, American Psychologist, pp. 819–834, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819.

[44] Lee, V. and D. Burkam (2003), “Dropping Out of High School: The Role of School Organization and Structure”, American Educational Research Journal, pp. 353–393, https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00028312040002353.

[61] Lyubomirsky et al. (2005), “The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success?”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. Vol. 131/(6), pp. pp. 803–855, https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

[41] Ma, X. (2003), “Sense of Belonging to School: Can Schools Make a Difference?”, The Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 96/6, pp. 340-349, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670309596617.

[78] McDaid, D., E. Hewlett and A. Park (2017), Understanding effective approaches to promoting mental health and preventing mental illness, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/bc364fb2-en.

[94] McGurk, H. (ed.) (1992), Friendships and their developmental significance, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

[45] McWhirter, E., E. Garcia and D. Bines (2018), “Discrimination and Other Education Barriers, School Connectedness, and Thoughts of Dropping Out Among Latina/o Students”, Journal of Career Development, pp. 330–344, https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845317696807.

[82] Ministério da Saúde (2020), Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde do Escolar (PeNSE): o que é, para que serve, temas [National Student Health Survey (PeNSE): what is it, what is it for, themes], http://antigo.saude.gov.br/saude-de-a-z/pense (accessed on 13 October 2020).

[69] Morgan, A. et al. (2007), Mental well-being in school-aged children in Europe: associations with social cohesion and socioeconomic circumstances, https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/74751/Hbsc_Forum_2007_mental_well-being.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2020).

[48] MultiRio (2017), Projeto fortalece sentimento de pertencimento dos alunos à E.M. Bernardo de Vasconcellos [Project strengthens students’ sense of belonging to E.M. Bernardo de Vasconcellos], http://www.multirio.rj.gov.br/index.php/leia/reportagens-artigos/reportagens/13383-projeto-fortalece-sentimento-de-pertencimento-dos-alunos-%C3%A0-e-m-bernardo-de-vasconcellos (accessed on 20 October 2020).

[38] Nocentini, A. and E. Menesini (2016), “KiVa Anti-Bullying Program in Italy: Evidence of Effectiveness in a Randomized Control Trial”, Prevention Science, Vol. 17/8, pp. 1012-1023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0690-z.

[64] OECD (2020), Combatting COVID-19’s effect on children, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=132_132643-m91j2scsyh&title=Combatting-COVID-19-s-effect-on-children (accessed on 11 October 2020).

[66] OECD (2020), Learning remotely when schools close: How well are students and schools prepared? Insights from PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/learning-remotely-when-schools-close-how-well-are-students-and-schools-prepared-insights-from-pisa-3bfda1f7/ (accessed on 16 December 2020).

[60] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Surveys: Brazil 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/250240ad-en.

[84] OECD (2019), Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

[79] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b25efab8-en.

[58] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Database, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

[12] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives, PISA, https://doi.org/10.1787/acd78851-en.

[59] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Brazil 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-bra-2018-en.

[42] OECD (2017), PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264273856-en.

[23] OECD (2015), Do teacher-student relations affect students’ well-being at school?, http://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/pisainfocus/PIF-50-%28eng%29-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

[70] OECD (2015), Skills for Social Progress: The Power of Social and Emotional Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en.

[9] OECD (2013), “PISA 2012 Results: What Makes Schools Successful? Resources, Policies and Practices (Volume IV)”, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201156-en.

[89] OECD (2011), Doing Better for Families, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264098732-en.

[25] Oliveira, W. et al. (2015), “The causes of bullying: results from the National Survey of School Health (PeNSE)”, Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, Ribeirão Preto, Vol. 23/2, https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-1169.0022.2552.

[54] Ozer and Bandura (1990), “Mechanisms governing empowerment effects: A self-efficacy analysis”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. Vol. 58/(3), pp. pp. 472-486, https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.58.3.472.

[3] Pacífico, M., M. Facchin and F. Corrêa Santos (2017), “Crianças também se estressam? A influência do estresse no desenvolvimento infantil [Do children also get stressed? The influence of stress on child development]”, Temas em Edução e Saúde, Vol. 13/1, pp. 107-123, https://doi.org/10.26673/rtes.v13.n1.jan-jun2017.8.10218.

[62] Park N. (2004), “The role of subjective well-being in positive youth development”, The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. Vol. 591/(1), pp. pp. 25-39, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260078.

[72] Paus, T., M. Keshavan and J. Giedd (2008), “Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence?”, Nature reviews. Neuroscience, Vol. 9, pp. 947–957, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2513.

[7] Picus, L.O. et al (2005), “Understanding the relationship between student achievement and the quality of educational facilities:”, Peabody Journal of Education, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, London, UK, Vol. Vol. 80/3, pp. pp. 71-95, https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327930pje8003_5.

[68] Pollard, E. and P. Lee (2003), “Child Well-being: A Systematic Review of the Literature”, Social Indicators Research, pp. 59–78, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021284215801.

[47] Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro (2017), Futuro em construção na Vila Cruzeiro [Future under construction in Vila Cruzeiro], http://www.pcrj.rj.gov.br/web/sme/exibeconteudo?id=7317107 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

[28] Presidência da República (2015), Lei Nº 13.185, de 6 de Novembro de 2015 Institui o Programa de Combate à Intimidação Sistemática (Bullying) [Law Nº 13.185 of November 6th 2015: Institutues the Programme against Systematic Intimidadion (Bullying)], Presidência da República, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2015/lei/l13185.htm (accessed on 17 June 2020).

[86] Presidência da República, Casa Civil (2007), Decreto nº 6.286 de 05 de dezembro de 2007 [Decree No. 6,286 of December 5, 2007], http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=1726-saudenaescola-decreto6286-pdf&category_slug=documentos-pdf&Itemid=30192 (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[33] Raskauskas, J. (2007), “Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents”, Developmental Psychology, pp. 564–575, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564.

[91] Reitz, A. et al. (2014), “How Peers Make a Difference: The Role of Peer Groups and Peer Relationships in Personality Development”, European Journal of Personality, pp. 279-288, https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1965.

[56] Sagar, S., D. Lavallee and C. Spray (2007), “Why young elite athletes fear failure: consequences of failure”, Journal of Sports Sciences, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410601040093.

[14] Salata, A. (2019), “Razões da evasão: abandono escolar entre jovens no Brasil [Reasons for dropout: school dropout among young people in Brazil]”, Interseções [Online], http://journals.openedition.org/intersecoes/310 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

[31] Salmivalli, C., A. Kärnä and E. Poskiparta (2011), “Counteracting bullying in Finland: The KiVa program and its effects on different forms of being bullied”, International Journal of Behavioral Development, Vol. 35/5, pp. 405-411, https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411407457.

[32] Salmivalli, C., A. Kaukiainen and M. Voeten (2005), “Anti-bullying intervention: Implementation and outcome”, British Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 75/3, pp. 465-487, https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905x26011.

[87] Saúde Brasil, Governo Federal (2017), Recomendações do tempo da atividade física por faixa etária [Time recommendations for physical activity by age group], https://saudebrasil.saude.gov.br/eu-quero-me-exercitar-mais/recomendacoes-do-tempo-da-atividade-fisica-por-faixa-etaria (accessed on 12 October 2020).

[15] Schwartzman, Simon (2005), Os desafios da educação no Brasil [The education challenges in Brazil], Nova Fronteira, http://www.schwartzman.org.br/simon/desafios/1desafios.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2020).