3. Use of evidence in strategic planning and budgeting in Haiti

Haiti has adopted two major inter-ministerial strategies, which aim to make the country an emerging power by 2030. Their implementation will be based, among other things, on the development of a multi-year budget in line with the country's strategic priorities, the foundation for which is currently being laid. Capacity building and the establishment of an institutional framework for monitoring and evaluation would also make it possible to better measure the performance of public initiatives in relation to the country's development goals.

Haiti has set ambitious development goals, formalised in a multi-level strategic planning framework, with the intention of making the country an emerging power by 2030. This means that the Strategic Development Plan for Haiti 2012-2030 (PSDH) has become the reference framework for the country's long-term development, while the State Modernisation Programme 2018-2023 (PME-2023) aims to strengthen the effectiveness of public intervention. For strategic planning to be effective, the public policy priorities it proposes must be specific and measurable and limited in number. Haiti's whole-of-government strategies, however, suffer from methodological problems that affect their implementation.

The budget is also a powerful planning tool, reflecting the government's strategic priorities. Effective multi-year budgeting has a major role to play in this regard. In Haiti, legislative reforms have led to significant progress in this area, although the fundamentals of public finance still need to be consolidated. Performance budgeting is another way to ensure that the budget is aligned with the country's strategic priorities. It allows governments to check on a regular basis that the strategic goals, for which budgetary resources have been allocated, have been achieved. However, there is still a long way to go before public finances are managed in this way in Haiti. Multi-year budgeting must be firmly established, and the foundations for a programme budget must be laid. Performance budgeting can only be considered once these steps have been taken. In addition, the practice of gender budgeting, in its contribution to gender equality, is an important dimension of performance budgeting. This is a key subject of study for the OECD, which has published several reports in this area, such as "Gender budgeting in OECD countries" (Downes, Von Trapp and Nicol, 2017[1]). However, gender budgeting is not the focus of this chapter, which is devoted to the use of evidence in strategic planning and budgeting. Once the basic elements of performance budgeting are in place, Haiti can consider implementing gender budgeting. In addition, the topic of gender budgeting in the Haitian context has been studied by many national and international institutions and is accordingly deliberately left outside the scope of this Review.

The establishment of a robust system for monitoring and evaluating public policies will also be essential to improve public intervention with regard to Haiti's development goals. Monitoring and evaluation provide crucial evidence of the performance of public policies, which can improve their implementation and increase their transparency for stakeholders and citizens. In Haiti, the institutional framework for monitoring and evaluation will need to be strengthened and clarified to further embed the practices within government. Capacity-building and skills development will also be essential to make monitoring and evaluation a reality in Haiti, especially in the context of the country's post-crisis recovery.

In this context, this chapter looks at how the foresight, planning, programming, budgeting, monitoring and evaluation chain is implemented in Haiti within the context of the PSDH and the PME-2023. The first section analyses these two whole-of-government strategies with regard to good planning practices that enable the proper implementation of the public policy goals they enshrine. The second section analyses the Haitian government's efforts to align the budget cycle with strategic planning. Finally, the third section examines how Haiti can put in place a solid system for monitoring and evaluating public policies.

Haiti has embarked on a process of structural reform, anchored in two main whole-of-government strategic documents

For several decades now, Haiti has faced great political instability, in addition to various health crises and natural disasters. Haiti was particularly hard hit by the earthquake of 12 January 2010, which devastated the country's infrastructure. On the economic front, the country suffered two consecutive years of recession in 2019 and 2020 (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020[2]). For 2021, the Haitian government is stimulating recovery through strong public investment and job creation policies, as well as an expansionary fiscal policy. However, the COVID crisis is slowing down these efforts considerably and is expected to cause, in particular, a 5.4% contraction in GDP in 2020.

It is in this context, and more particularly in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, that the government has shown its ambition to undertake far-reaching reforms in order to improve governance, develop the economy and strengthen the fabric of Haitian society. In recent years, the Haitian government has embarked on a process of structural reform to improve development management (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2020[3]). These efforts are reflected in the continuation of State reform, the renewal of the national development planning and management system and the improvement of budgetary programming for "the implementation of the PPPBSE chain (Prospective, Planning, Programming, Budgeting, Monitoring and Evaluation)" (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2020[3]).

In line with the development planning approach implemented in the country since the 2000s, the government has formalised these reform projects in a transversal, multi-year strategic document: the Haiti Strategic Development Plan for Haiti for 2030 (Plan Stratégique de Développement d’Haïti - PSDH) (Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti, 2012[4]). The realisation of the PSDH’s vision to have the country emerge by 2030 requires its implementation through successive three-year investment plans (Plans triennaux d’investissement - PTI), which are the tools for its execution in the medium term and the articulation between these goals and the budget. However, since the adoption of this development strategy, the Haitian state has only been able to perform one PTI, that of 2014-2016 (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2020[3]).

In order to support these ambitions and successfully implement the public governance reforms essential to achieving Haiti's development goals, the government elected in 2017 has developed the State Modernisation Programme 2018-2023 (Programme de Modernisation – PME 2023). There are other strategic planning documents in Haiti, such as the Reform of Public Finance and Economic Governance Strategy (Stratégie de réforme des finances publiques et de gouvernance économique - SRFP) put in place by the decree of 9 October 2015 (Journal Officiel de la République de Haiti, 2015[5]). The Government of Haiti has also developed strategic programming instruments in collaboration with the technical and financial partners to clarify the goals and expected results of international development assistance. This is the case, for example, with the Sustainable Development Framework (Cadre de développement durable - CDD 2017-2021), which expresses the common will of the Republic of Haiti and the United Nations to place the country on the path of sustainable development (Gouvernement d'Haïti et Nations Unies, 2017[6]). However, the PSDH and the PME-2023 are the main transversal instruments for the country's development in the medium and long term.

As such, Haiti’s efforts are in keeping with growing government interest in long-term planning, both at the national and territorial levels (Máttar and Cuervo, 2017[7]). This global trend is related to two main factors:

At the international level, governments wish to be accountable for achieving the sustainable development goals of the UN 2030 Agenda (ONU, 2015[8]).

At the national level, governments recognise the need to ensure continuity of development policies across electoral cycles.

Box 3.1 presents some examples of these long-term strategic planning approaches.

There are many long-term strategic planning instruments developed by international organisations or governments.

The 2030 Agenda is a development agenda adopted in 2015 by the 193 members of the United Nations, which aims to foster peace and prosperity through the eradication of poverty and the transition to sustainable development. This universal programme is broken down into 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 priority targets. Each goal is associated with a number of statistical indicators to monitor its achievement at the local, national and international levels.

The African Agenda 2063 is a blueprint for transforming the African continent into a global powerhouse, based on sustainable and inclusive development. Its aspirations include economic prosperity based on sustainable development, good governance and the maintenance of peace and security. In order to achieve the goals set out in this plan, Agenda 2063 is broken down into several medium-term implementation plans.

At the national level, many governments have developed long-term strategic planning documents. In South Africa, for example, the National Development Plan 2030 identifies key challenges to accelerate the country's development, including the eradication of poverty and reducing inequality. The document states that the plan will be implemented in three phases and that the strategic planning instruments of the various government institutions and entities must be aligned with it.

Source : https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/; https://au.int/fr/agenda2063; https://www.gov.za/issues/national-development-plan-2030

The implementation of a new development logic with the PSDH in 2012

In 2012, with the help of the technical and financial partners (TFPs), the government added further depth to the four main initiatives or building blocks of the PARDH in the Strategic Development Plan for Haiti (PSDH) (Gouvernement de la République d’Haïti, 2012[4]). The Haitian PSDH has thus become Haiti's overall strategic reference framework for planning the country's development. The PSDH is based on four main pillars: strong economic growth, a balanced development framework, social reform to reduce inequalities and improve social cohesion and institutional reform through the in-depth reforml of public institutions and administrations. Box 3.2 provides more information on the development and content of the strategy.

The PSDH 2030 is the planning document setting out in detail the vision for Haiti's emergence by 2030. Its objectives include:

"Accelerated economic growth and strong job creation, without which our environmental and social vulnerability will increase";

"A decrease in our population growth, which slows our standard of living and increases the pressure on natural resources";

"Wiser use of land to protect the country's natural and cultural heritage, improve housing conditions and reduce environmental degradation";

"A better spatial distribution of development efforts to counter the current strong centralisation of the country";

"Greater social redistribution of the fruits of economic growth, which is necessary to meet social needs, especially in education and health";

and "a significant strengthening of the rule of law, both in terms of justice and security and in terms of respect for the law."

Since 2012, the PSDH has been the reference tool for the Haitian state's long-term planning. It consists of four major projects: territorial restructuring, economic restructuring, social restructuring and institutional restructuring, which are implemented through 32 programmes.

In particular, it is implemented successively through seven three-year PSDH implementation frameworks, each accompanied by a three-year investment programme (PTI).

Source: Haiti Strategic Development Plan (2012-2030).

The institutional dimension of the PSDH is linked to the PME-2023, which reflects the current government's goals for modernising the State

In order to revive the momentum for modernising the state apparatus and improving public governance, which had stalled after the failure of two state reform framework plans, the new Haitian government adopted the State Modernisation Programme in 2018 for a period of five years (PME-2023). This programme, supported by the Office of Management and Human Resources (Office de Management et des Ressources Humaines - OMRH), which reports to the Prime Minister, aims to create a dynamic for the transformation of public intervention and to establish a relationship of trust between users and the administration. The PME-2023 has 6 main goals:

"To improve the quality of services while developing a relationship of trust between users and the administration´;

"To provide a modern working environment for civil servants by involving them fully in the definition and monitoring of the modernisation project´;

"To rethink and optimise public spending to achieve better delivery of public services at lower cost´;

"To improve human resources management by establishing a more attractive and competitive public service that respects equal opportunities, gender equality and equity, the rights of people with disabilities and special needs, ethical and professional principles and the promotion of merit and excellence";

"To transform the public administration so that it is able to propel the country's development and its emergence by 2030", and

"To establish structures that prevent, expose and combat corrupt practices in order to develop a culture of good governance".

The PSDH and the PME-2023 have methodological limitations that could limit their effectiveness as long- and medium-term strategic planning instruments

The operationalisation of a strategic planning instrument depends primarily on the definition of clear and measurable public policy goals and their budgeting (OECD, 2018[9]) . In Haiti, as the PSDH 2030 is a long-term planning instrument, its operationalisation must be based primarily on a linkage with medium-term strategic planning instruments such as the PME-2023. However, while the PME-2023 contains clear and measurable goals, the articulation of this programme with the PSDH on the one hand, and with the budget on the other, is insufficient – which thus risks compromising the operational implementation of these strategies.

The PME-2023 has clear public policy goals that can be measured by indicators

The definition of quality public policy goals is a necessary precondition for the implementation of any strategy. The goals indicate the direction of the reforms to be carried out and underpin the actions to be implemented. In principle, a strategic plan should present general goals (broad area of reform) and more specific goals (concrete results on an aspect of the general goal). A goal should be stated in clear language, without jargon or complex phrases, so that it can be understood by all stakeholders and the general public (OECD, 2018[9]) . In general, the quality of a goal can be assessed according to the "SMART" model:

Specific: a goal must be concrete, describe the results to be achieved, be targeted and contribute to the resolution of the problem;

Measurable: a goal must be expressed numerically and quantifiably in relation to a predefined benchmark or target;

Achievable: a goal must be a stimulus for action and improvement of the existing situation, but it must also be achievable to serve as a management tool;

Realistic: a goal must be realistic in terms of the time available to achieve it and the resources available;

Timeframe: the period of time for achieving a goal must be specified.

It is the indicators, associated with their targets and reference values, that make a goal measurable and deployable over time. It is necessary to define explicit goals in terms of expected results. The more ambiguous a goal is in terms of its results, the more difficult it will be to associate a relevant indicator with it (Schumann, 2016[10]).

The goals defined in the PME-2023 are thus broken down into three levels: a general level, the "axis", and two more specific levels, the "immediate results" and the "expected results". This tiered approach is supported by a clear logical model, which allows for solid milestones to be set for the implementation of the PME-2023 and its evaluation. Indeed, the different levels of goals in a strategy must follow a logical hierarchy. Developing a causal chain (a theory of change) or logical model helps to understand how an intervention, programme or public policy is expected to bring about a particular change and have an impact. It is accordingly an evidence-based causal analysis that theorises how public policy inputs should lead to intended impacts and goals (Groupe des Nations Unies pour le Développement Durable, 2017[11]). Box 3.3 below explains in more detail how the development of a theory of change or logical model can facilitate the implementation and evaluation of a programme, policy or strategy.

A theory of change is a method for tracing or identifying the ways in which a public intervention (policy, programme, project, etc.) or series of interventions will lead to specific changes, based on evidence-based causal analysis. It has several goals:

1. The evaluability of the programme or public policy - both for implementation and for outcomes - is enhanced by identifying appropriate metrics.

2. The intentions of the policy or programme designers are clearly stated, and are explicit and open to discussion.

3. The underlying logic of the assumptions made in the theory - for example, the theory that undertaking a certain activity will lead to a certain outcome - can be clearly examined.

4. The realism of the assumptions made in the programme or policy can be tested against broader evidence of successful programmes, thereby assessing the likelihood of success.

5. Evaluation officers can test whether the programme or policy meets their needs, and providers and practitioners administering the programme can test their own assumptions and expectations against the original intentions of the programme designers.

6. Key parameters (e.g. who the programme is intended for) can be easily defined, reducing the likelihood that the programme will be used inappropriately or inefficiently.

7. The main elements - of content and/or implementation - that are considered essential to the effectiveness of the programme can be identified.

9. The most important features of the programme deployment model can be captured, allowing for delivery that adheres to the original model and helps prevent programme drift during scaling.

Source: Adapted from United Nations Development Group - UNDG (2017[11]), Theory of Change: UNDAF Companion Guide. https://undg.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/UNDG-UNDAF-Companion-Pieces-7-Theory-of-Change.pdf Ghate, D. (2018), « Developing theories of change for social programmes: co-producing evidence-supported quality improvement », Palgrave Communications, Vol.4/1, p. 90, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0139-z

In addition, each "expected result" of the PME-2023 is associated with one or more performance (output) indicators to measure its achievement. However, "intermediate results" are not associated with outcome indicators. The development of such indicators would facilitate the implementation and monitoring and evaluation of the PME-2023 (see section three for more information on monitoring and evaluation of the PME-2023). In addition, for an indicator to provide decision-makers with relevant information on the achievement of the policy goal, it must be accompanied by elements that allow for its correct interpretation (OECD, 2018[9]). These elements include the reference value or baseline of the indicator and the final target values for defining its satisfaction.

There is no clear and explicit logical framework for the articulation of long and medium term strategic planning instruments

Clearly and explicitly articulating strategic planning instruments enables governments' limited resources to be focused on a few policy priorities, while clarifying how these efforts contribute more broadly to other stated ambitions. In Haiti, the existence of several whole-of-government strategies is not a problem in itself, as they have different time horizons. However, clarifying their relationship through a logical model would ensure their effectiveness.

This means that the articulation between the PME-2023 and the PSDH is an issue. Indeed, the State Modernisation Programme is in line with the PSDH. The PME-2023 states that "the State Modernisation Programme (PME-2023) [...] is consistent with the various projects of the PSDH" (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2018[12]). The PME-2023 itself states that it "will be aligned with the PSDH to maximise the chances of its successful anchoring on existing implementation arrangements". Indeed, the articulation of the different strategic planning instruments of a country is an important issue in order to concentrate efforts and public resources on a limited number of goals to be achieved.

However, there is currently no explicit logical framework to ensure the articulation and coherence of these two documents. The inclusion of indicators with clear final target values in the PME-2023, as well as in the PSDH, would also help to clarify the articulation between these two instruments.

The operationalisation of the PME-2023 in an action plan and its articulation with the budget remain to be established

International good practice stresses the need to develop action plans in conjunction with strategic planning to define the timetable for implementation, responsibilities and budget for each goal. The PME-2023 requires sector ministries to develop an action plan, assess the cost of implementing the goals assigned to them, and establish an implementation schedule. These action plans were presented at the final seminar of the PME-2023 Operationalisation Mission Phase II held on 23 March 2021.

The use and follow-up of these action plans will be essential to clarify the terms of implementation of the PME-2023, to ensure the articulation of this plan with the budget and to lay the foundations for the monitoring and evaluation system of this plan. Similarly, the gradual introduction of performance-based budget programming will make it possible to improve the linkage of the PME-2023 with the budget and a fortiori its implementation. The next section of this chapter details the precise terms of such an articulation.

Strategic decision-making requires access to solid, credible data

More generally, policy-making requires access to solid and credible evidence. This includes encouraging research and good records management. The government has a research and documentation centre (Centre de Recherche et de Documentation - CREDOC), which forms part of the Office of the Prime Minister. The Haitian government could rely on CREDOC to access information useful for strategic decisions.

The budget cycle could further support the implementation of the Haitian government's policy goals

The strategic phase of the budget is essential to align the budget with the strategic priorities of governments

The OECD recommendation on budgetary governance (see Box 3.4) states that budgets should be closely aligned with medium-term policy priorities through two main mechanisms:

This articulation corresponds to the goal of the strategic phase of the budget, which aims to balance the limited resources available against the government's spending aspirations and arbitrate between the various policy priorities of the government that cannot be achieved simultaneously in a single financial year. While not a strategic plan, the budget is thus a planning tool to achieve the goals set by the government (Long and Welham, 2016[13]).

In an annual budget cycle, the strategic phase of the budget usually begins with the presentation of the budget overview, which expresses a request for policy orientation from the administration. The quality of the data on which the analysis of past fiscal years is based is critical to the credibility of the budget forecasts. From the overview presented, the government clearly communicates the goals and budgetary constraints. The managing sectors and services then establish their costs and forward them to the budgetary authority which ensures these expenditures by individual departments are aligned with the priorities set by the government. The strategic phase ends with the publication of a "budget circular" (circulaire budgétaire) indicating the budget ceilings and including other guidelines for the preparation of the budget for the institutions responsible for expenditure. This is the beginning of the budget preparation phase.

Closely align budgets with the medium-term strategic priorities of government:

developing a stronger medium-term dimension in the budgeting process beyond the traditional annual cycle;

organising and structuring the budget allocations in a way that corresponds readily with national objectives;

Recognising the potential usefulness of a medium-term expenditure framework (MTEF) in setting a basis for the annual budget, in an effective manner which:

has a real force insetting boundaries for the main categories of expenditure for each year of the medium-term horizon

is grounded upon realistic forecasts for baseline expenditure (i.e. using existing policies), including a clear outline of key assumptions used

shows the correspondence with expenditure objectives and deliverables from national strategic plans; and

includes sufficient institutional incentives and flexibility to ensure that expenditure boundaries are respected

nurturing a close working relationship between the Central Budget Authority (CBA) and the other institutions at the centre of government (e.g. prime minister’s office, cabinet office or planning ministry), given the inter-dependencies between the budget process and the achievement of government-wide policies;

considering how to devise and implement regular processes for reviewing existing expenditure policies, including tax expenditures (see recommendation 8 below), in a manner that helps budgetary expectations to be set in line with government-wide developments.

Source: adapted from the OECD Council Recommendation on Budgetary Governance. (OECD, 2015[14])

Important reforms in this direction are underway

Improved budgeting and strategic planning are key reforms for public finances in Haiti. One of the main expected results of Axis 8 of the PME-2023, dedicated to the overall budgetary framework is the following: "The main economic and social development sectors have sectoral strategies and multi-year programmes with budget allocations in line with public policies and the resources available to the State” (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2018, p. 61[12]). Similarly, improving budgetary planning, through a medium-term expenditure framework, and introducing programme-based budgeting are two of the main areas identified by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) in its reform of the public finance strategy.

OECD discussions with the Haitian administration have indicated that the legislative framework has been amended, including by the law of 4 May 2016 on the process of drafting and executing finance laws, to modernise the budget cycle in Haiti and move it from a means-based to a results-based approach. Legislative reforms in the budgetary area have been among the most successful in recent years in Haiti. The Law of 4 May 2016 (République d'Haiti, 2016[15]) establishes a medium-term budgetary framework, with a three-year horizon, in line with the three-year investment programmes (PTIs).The Act also introduced programme-based budgeting and a medium-term expenditure framework.

In practice, however, these instruments are not yet operational. In a pilot experiment, the budget programmes of two ministries have been introduced and presented in the Finance Bill 2018-2019. In regard to the progress of a medium-term budgetary framework, overall financial projections are not yet available. In the OECD questionnaire administered to the Haitian authorities in the context of this Review (hereinafter "the OECD questionnaire"), the Office of the Prime Minister states that there are no institutional mechanisms in place to ensure the harmonisation of strategic planning and resource allocation in the annual or medium-term budgetary goals. This is not a new problem: it was pointed out in the latest available report on Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) regarding1 alignment with the document National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (Stratégie nationale pour la croissance et la réduction de la pauvreté - DSNCRP) (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]) and more recently in a World Bank report (2016[17]).This is primarily due to a lack of capacity and resources. In addition, there are no institutional incentives in Haiti to ensure compliance with spending limits, as recommended by the OECD (OECD, 2015[14]).

The interviews revealed that the programming and study units (Unité d’Étude et de Programmation - UEP) still lack capacity in budgeting and strategic planning. The sectoral strategic plans are not sufficiently developed. In the budget preparation phase, these plans should include cost reports. However, the latest available PEFA report indicates that cost reports, where they exist, cover only a small portion of the Haitian government's expenditure (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]). In addition, multi-annual cost reports are one of the foundations of the medium-term budgetary framework. These are almost non-existent in Haiti (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]). On the other hand, public policy goals, in line with the priorities defined by the government, which are themselves aligned with the PSDH, are rarely associated with the determination of expenditures (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]). This is primarily due to the lack of human resources in the UEPs: many of them are not functional. In response to this difficulty, the Ministry of Planning and External Cooperation (Ministère de la Planification et Coopération Externe - MPCE), the central actor in strategic planning, centralises and coordinates strategic budgeting through the Unit Coordinators' Forum. It holds regular working sessions with UEPs to discuss technical issues and strategic priorities. The MPCE is accordingly involved in strategic budgeting through an informal coordination mechanism.

Similarly, there is a lack of resources to identify and carry out public investments. The World Bank (2016[17]) report shows that preliminary analyses of investment projects are not sufficiently developed. Financial and strategic documentation for many investment projects is lacking, making it impossible to establish an adequate link to strategic planning. In addition, some projects are abandoned midway or transformed, creating a deviation from the strategic plans. For this reason, the IMF (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]) calls for an investment plan that would facilitate medium-term budgeting. For Fiscal Year (FY) 2017-18, the MPCE, which is in charge of most of the capital expenditure, is thus the department with the lowest budget performance rate for FY 2017-18 (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]).

Macroeconomic and macro-fiscal forecasts are also essential to ensure the credibility of a medium-term fiscal framework. These are still new in Haiti and need to be further developed. A team dedicated to macroeconomic and macrofiscal forecasting was created in 2013. A multi-year macroeconomic framework was prepared for the first time in FY 2018-19 (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]). The absence of a number of data, including national accounts data since end-2018 (Fonds Monétaire International, 2020[20]), and the lack of sophistication of the forecasting model used - highlighted during the OECD fact-finding mission - suggest that the macroeconomic forecasting work needs further refinement. The macro-budgetary aspect is just beginning to be introduced. Only the tax revenue projections were inserted in the preparation for the 2018-2019 financial year. Projections of government expenditure and overall budget balances are planned for the coming years.

Strengthening the fundamentals of public finances is an essential condition for the implementation of programmatic and results-based budgeting

Effective treasury management and budget implementation, whole-of-government budgeting, comprehensive and reliable budget reporting and the certainty of administrative entities that funds will be available for planned expenditures are fundamental elements that must be in place to manage an annual budget and to consider multi-year budget management. If carefully designed, the medium-term budget framework can clearly illustrate the impact of existing government policies on revenues and expenditures. It is also a tool to monitor the introduction of new policies and to track budget implementation on a multi-year basis. It provides a transparent basis for the implementation of accountability and for the preparation of more detailed, results-based budgets. It is used to assess government accountability and to prepare detailed, results-based budgets (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]). The basic principles presented in this section must become self-evident to the Haitian state before considering programmatic budgeting first and performance budgeting second.

Treasury management efforts in Haiti must not be relaxed

Treasury management in Haiti is a long-standing weakness, identified in the latest available PEFA report (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]), a World Bank report (Groupe de la Banque Mondiale, 2016[17]) and a recent IMF report (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]). Its importance is recognised in the PME-2023 plan: For example, "ensuring the consolidation of the single treasury account" is one of the goals of Axis 9 on treasury and public accounting (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2018, p. 62[12]). This is also a clear goal of the MEF in its reform of public finance strategy.

Much work has already been done with the assistance of the IMF to consolidate the government's account balances in the Single Treasury Account (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]). The continued existence of several dozen accounts with the Bank of the Republic of Haiti, however, complicates cash management planning. Traditionally, this persistence is often due to the refusal of some managing services to lose control of their account. There are many reasons for this: among others, the lack of confidence in centralised management of financial funds or the desire to preserve a form of opacity in the use of public funds by avoiding the administrative controls of the budgetary authority. A single cash account is an effective mechanism for planning, managing and monitoring budget implementation. Such an account streamlines payments and reduces the backlog of new expenditures. It would also reduce the cost of financing the government by the Central Bank and improve financial transparency.

In the absence of a single, comprehensive cash account, the release of cash based on liquid funds rather than on budget could persist, which is a constraint to strategic budgeting. Government agencies have little reason to pursue the strategic phase of the budget if the funds they can receive do not match their budget proposals. The certainty required by the administrative sectors is also based on credible macroeconomic and fiscal forecasts.

Transparency of public finances must be increased

The Review of past budget years at the beginning of the strategic phase should be based on financial and accounting reports. The seventh principle of the OECD Recommendation on Budgetary Governance states that "these reports play a fundamental role in transparency and can, if well designed, provide useful messages on performance and value for money to inform future budget allocations" (OECD, 2015[14]).

The coverage and quality of financial accounts should be improved to facilitate the monitoring of public finances. The government's financial transactions table (FTT), published monthly, has some weaknesses, including limited coverage, a high level of aggregation and inaccurate classification (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]). The creation of some institutions by decree, such as OMRH, is an obstacle to their inclusion in the budget. Similarly, better disclosure of certain budgetary expenditures, as well as the accounts of autonomous agencies and public enterprises, would improve transparency (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]).

Budgetary control and performance need to be improved

Effective parliamentary oversight of the budget is one of the goals of Axis 10 on external oversight and transparency of the PME-2023 (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2018[12]). The involvement of the legislature in the development of the budget is essential. It must be able to discuss policy priorities and contribute to the arbitration of the resources available to the State to implement these priorities. The Haitian statutory framework institutes a fixed budgetary calendar (Table 3.1) but the budget is rarely ratified by Parliament (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]) (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]), as Parliament is seldom sitting. When this is the case, it is either incomplete or submitted too late in the fiscal year. This means that since the year 2016, only one finance law has been approved by Parliament. In the absence of such approval, the State must renew the last budget ratified by Parliament.

The use of letters of transfer (lettres de virement) to pay for government expenditures should be reduced. The increase in the use of this exceptional expenditure procedure in recent years, which circumvents internal expenditure control, undermines budgetary transparency and accountability.

Budget performance in Haiti is still a significant challenge (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]; Groupe de la Banque Mondiale, 2016[17]). Poor budget management control is traditionally associated with higher levels of expenditure arrears, but also with a lack of budget credibility and poor quality of budget preparation. The implementation rate of capital expenditure in Haiti is particularly low. Indeed, between 2013 and 2018, this rate was about 41% (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]). These difficulties reflect the lack of resources needed to identify and implement public investments, as discussed above (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]).

It is important to lay the foundations for more ambitious reforms

In parallel with the completion of the public finance fundamentals described above, Haiti can better articulate the strategic planning and budget cycles in order to move towards modern public financial management. This articulation is a challenge in all countries, including the most developed ones. For example, the harmonisation of time horizons within the European Union is not yet complete (Downes, Moretti and Nicol, 2017[21]). The EU's medium-term budgetary framework, known as the "Multiannual Financial framework", has a seven-year horizon, while the main strategic planning tool, "Europe 2020", has a ten-year horizon. Synchronising these two horizons would strengthen the alignment between budgeting and planning. In addition, the OECD noted the importance of reviewing the Europe 2020 strategic plan at mid-term, and of using this assessment to conduct a public expenditure review.

The reforms underway in Haiti - programme-based budgeting, the medium-term budget framework, the medium-term expenditure framework, strategic planning - provide the basis for this linkage between strategic goals and the budget cycle. The points discussed below are essential for these reforms to support a budget architecture that is synchronised with strategic planning. The experience of Thailand, South Korea and Romania can accordingly be instructive for the reform of public finances underway in Haiti.

Articulating the timing of strategic planning and budget preparation

The medium-term budgetary framework is theoretically prepared between July and November of each year by the MEF (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]). After its presentation to the Council of Ministers and approval, it is transmitted to the sectors so that they can in turn prepare their medium-term budgetary framework.

In preparing the budget, the indicative expenditure envelopes contained in the circular of 15 October requesting ministries and agencies to submit their budget proposals must be broken down by sector. The latest available PEFA report suggests (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]) that this is not the case in practice and that it is not envisaged in the budget preparation procedures manual.

In the past, managing departments and agencies have had limited time to develop their budget proposals (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]).It is crucial that these entities have sufficient time to develop expenditure estimates. Managing departments and agencies must feel fully involved in and accountable for the budget process, including its contribution to strategic planning. This then affects the credibility of the budget and its implementation. This involvement is also crucial to the success of a programmatic structure (Box 3.6).

The fact-finding mission also revealed that the macroeconomic framework for budget planning was carried out between March and June, in parallel with the preparation of the budget. However, these macroeconomic and budgetary forecasts form the basis for a medium-term budgetary framework, which is normally prepared between July and November. This lack of consistency over time does not allow for a credible medium-term budgetary framework. This work by the Economic Studies Directorate must accordingly be carried out further ahead of the budgetary calendar.

Linking budget documentation to strategic planning

A functional classification of expenditures in the budget nomenclature promotes consistency between the budget cycle and strategic planning by measuring progress against strategic goals. It also promotes transparency vis-à-vis Parliament, citizens and the technical and financial partners.

In 2011, a functional classification was not yet in place in Haiti (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]). The budgetary nomenclature included only an administrative classification and an economic classification. A functional classification has since been established (Groupe de la Banque Mondiale, 2016[22]). This classification is similar to the 12-category Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG) developed by the OECD.

For budgeting to have a real strategic dimension, a functional classification must allow for the analysis of past budget years and the determination of budgetary perspectives for future years. This classification is present in the last two available schedules of the Finance Acts, i.e., those for financial years 2017-18 and 2020-21. It is also included in the latest available schedules to the Finance Bill, which are for the year 2017-18. However, in order to encourage budgetary accountability and transparency, this functional classification of performed expenditures should be made public on a regular basis. This is not the case today: only a very aggregated classification by nature is available. Discussions have revealed that efforts are underway to improve the fiscal nomenclature, in partnership with the IMF.

Strengthening institutional coordination

Lack of coordination affects the reliability and completeness of financial information

Externally funded capital expenditures, such as donor funds, constitute the vast majority of the total capital budget. Indeed, the 2017-2018 Supplementary Budget Act indicates that they account for 54.6% of that budget. However, reporting on projects funded and funds implemented is very incomplete (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]). This is a long-standing problem. For example, the 2012 PEFA report indicated that information on revenues and expenditures of donor-funded projects is not included in the monthly budget performance reports, nor in the annual budget performance reports submitted by the MEF (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]). In 2017, the Haitian government established a partnership framework for tax reform and public financial management to improve coordination between the various technical and financial partners and the Haitian administration (Fonds Monétaire International, 2019[18]). Such a tool should facilitate the integration of donor-funded projects into the budgeting process. In addition, Haiti can learn from the good practices of a number of African countries, such as Uganda and Tanzania (Collaborative Africa Budget Reform Initiative, 2008[23]).

There is no monthly MEF budget performance report covering all administrations (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]). Each jurisdiction generally publishes monthly reports on revenues and expenditures. This lack of clarity undermines budgetary transparency because it prevents policy makers, citizens and Parliament from having an overall infra-annual view of the country's budgetary situation.

Interviews with the Haitian administration revealed that a channel of communication between the Higher Court of Accounts and Administrative Disputes (CSCCA) and the General Inspectorate of Finance (IGF) located within the MEF, which was previously non-existent, is being established. This communication would ensure the transfer of information between internal and external auditors and thus improve the quality of financial reporting.

Lack of coordination hampers budget preparation, especially with regard to the predictability of expenditure

Responses to the OECD questionnaire also suggest that during the budget preparation phase, MEF does not have all the information necessary to ensure the authenticity of the budgets submitted by line ministries.

The latest available PEFA report (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012[16]) stresses that capital and operating budgets are separate processes. The MEF is in charge of the operating budget, while the MPCE manages the capital budget. These two institutions are not yet sufficiently coordinated to estimate the recurrent costs of capital expenditures (Commission économique pour l'Amérique latine et les Caraïbes, 2019[19]). From this perspective, the organisational structure of Thailand, East Timor and South Korea established to articulate budgeting and strategic planning is illuminating (Box 3.5).

Public investment programmes (PIPs) rarely include donor investment projects (Groupe de la Banque Mondiale, 2016[17]). These could result in unforeseen costs to the national budget. The 2012 PEFA points out that "budget support and project aid forecasts are not comprehensive and are not communicated to the MPCE and MEF departments in time to be taken into account in the budget law" (Morachiello and Lopke, 2012, p. 17[16]).

A strategic planning agency separate from the budget authority in Thailand

The medium-term fiscal framework in Thailand is prepared by four institutions that form the Fiscal Policy Committee. The Fiscal Policy Office within the Department of Finance is responsible for revenue, public debt and cash management, as well as sub-annual monitoring and reporting. The Budget Office is responsible for budget policy, planning and performance, and budget and expenditure estimates. The Central Bank of Thailand and the National Economic and Social Development Board are jointly responsible for macroeconomic forecasting. The Central Bank manages economic analysis and advice while the Council is the strategic planning agency.

A common budgeting and planning authority: the Economic Planning Commission in South Korea

In South Korea, from the early 1960s to the early 1990s, the Economic Planning Commission was responsible for strategic planning as well as budgeting. This institution was attached to the Deputy Office of the Prime Minister. The Commission has put in place a medium-term strategic plan, called the Economic Development Plan, with a five-year horizon, in which budgetary constraints are integrated. The Economic Planning Commission is also responsible for coordinating the design and implementation of these plans.

In Romania, the Ministry of Public Finance oversees the preparation of the medium-term budget.

The Romanian Ministry of Public Finance is responsible for the management of public finances in accordance with national and European rules. In this context, it prepares the fiscal and budgetary strategy, which sets out the country's medium-term fiscal framework. The Ministry of Public Finance also sets spending limits and prepares the Finance Bill by collating the proposals of the spending authorities. The Ministry also cooperates with the National Strategy and Forecasting Commission, which is a separate entity subordinate to the General Secretariat of the Government. It is officially responsible for the main macroeconomic projections, such as GDP or sectoral demand.

Source: (Blazey et al., 2021[24]); (Nicol and Park, 2020[25]), (Choi, 2015[26]).

Developing sectoral strategic plans

During the fact-finding mission, the Haitian administration has indicated that the budget cycle is aligned with the long-term strategic planning, i.e. the PSDH. However, the PSDH is too vague to facilitate the allocation of budgetary resources and the selection of investment projects. One obstacle is the lack of prioritisation in terms of importance and feasibility. Sectoral strategic plans, with strategic goals, should accordingly play a key role in budget planning. The OECD fact-finding mission to the Haitian administration revealed that efforts are underway to harmonise sectoral policies and strategies. It should be noted that some managing services are more advanced than others in developing multi-year strategic plans. These include the Department of Education and the Department of Public Health and Population.

In addition to contributing to a medium-term budget and expenditure framework, sectoral strategic plans can serve as an anchor for programme budgeting (Downes, Gay and Kraan, 2018[27]).Indeed, in many countries, programmes are selected in the context of a policy "cascade", starting from high-level strategic and development goals that feed into specific medium-term outcome goals, which in turn feed into ministerial or sectoral goals and associated outcome targets. International experience also indicates that reclassification of the budget on a programmatic basis is best achieved with well explained multi-year budget estimates, preferably formulated in terms of results. Once a medium-term, programme-based sector strategy is developed, countries can assign clear organisational and managerial responsibilities for achieving the selected plans and goals. Haiti can draw on the experience of East Timor, where medium-term planning is a precondition for the introduction of programme budgeting (Box 3.6).

The development of programme-based budgeting, and subsequently performance-based budgeting, are clear goals for the Haitian administration. But the road to achieving these goals is long. This chapter has detailed some of the aspects of a modern budget architecture, relating to the link between budgeting and strategic planning, that need to be understood in order to move forward on this path.

A strategic planning agency involved in budget planning, but separate from the budget authority.

The Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation Unit (PMU) is an agency within the Office of the Prime Minister of East Timor. It is responsible for coordinating, organising and supervising the planning, monitoring and evaluation process of all government policies and programmes, including the state budget. The PMU ensures that the annual plan is consistent with the strategic development plan and that the sectoral programmes are consistent with the annual plan and the strategic development plan. The Ministry of Finance is the budgetary authority that prepares and executes the budget. Management departments are responsible for developing sector plans and submitting budget proposals to the Ministry of Finance and the PMU for analysis. They are also responsible for monitoring the implementation of the annual plan and budget by their departments and for sending quarterly and annual reports on results to the PMU.

The gradual introduction of a programme-based budget

Following the approval of the Strategic Development Plan, which is the long-term strategic plan for East Timor, the Office of the Prime Minister took the initiative to develop a government planning process around programmes. For this purpose, it launched a pilot project in 2016 to establish a programmatic classification, in ten ministries and 15 autonomous agencies. One of the goals of the latter is to link programmes to the overall goals and vision defined in the strategic development plan and relevant sectoral plans. Sectoral, annual or medium-term plans were not yet fully integrated into budget planning. In particular, PMU trained departments on how to develop their programme structure, costing and monitoring. East Timor has also opted for a simplified approach, in which budget programmes correspond to ministerial portfolios, rather than being inter-ministerial or transversal.

The main difficulties encountered in this implementation

One of the main lessons learned from the experience of OECD countries and East Timor is to avoid information overload for managing ministries and autonomous agencies. During the preparation of the budget, the latter are often offered two frameworks for expressing their budgetary proposals: on the one hand, the structure by programme, and on the other, the traditional structure by budget item. Given the limited time available to complete these documents, the process of preparing annual and medium-term strategic plans must be streamlined and understood from the outset. For this reason, programme budgeting should be done downstream of strategic planning. The second lesson is the importance of information loops between participants so that reform is not understood as a "vertical" policy. The adherence of all participants to the programme structure is sometimes not achieved. All participants must feel responsible for the programmatic structure of the budget, not just its performance. The mechanisms of institutional coordination and ownership by ministries and autonomous agencies thus play a major role in the implementation of a programme budget.

Source: (Downes, Gay and Kraan, 2018[27]).

In addition to improving the quality of public financial management, monitoring and evaluation are used to improve the achievement of national development goals by providing critical evidence on how well the government is implementing these goals, and what has worked and what has not in the pursuit of these goals. Monitoring and evaluation also provide essential information to citizens on the performance of public policies.

A strong monitoring and evaluation system is essential to achieving the results of strategic planning

Monitoring and evaluation are two distinct practices

Monitoring and evaluation are two distinct practices, with different methods and goals. This means that monitoring aims to facilitate strategic planning and inform public decision-making by measuring the performance of reforms and identifying stress points and bottlenecks. It also strengthens the accountability of public decision-makers and public information on the proper use of resources (OECD, 2019[28]). Unlike evaluation, monitoring is accordingly characterised by routine and continuous data collection processes (Table 3.2).While policy evaluation aims to show the extent to which the observed outcome can be attributed to the policy intervention, monitoring provides descriptive information without establishing a causal link between a policy intervention and the observed outcomes.

Conversely, the specific goal of evaluation is to inform decision-makers about the success or otherwise of a public policy and to determine whether there is a causal link between the observed results and the policy in question. In this respect, assessment is an episodic process, tailored to a specific problem, with actions and resources targeted and personalised according to the assessment (OECD, 2020[29]). Evaluation, however, shares common goals with monitoring, namely to determine whether government efforts are achieving the intended results, whether value for money is being achieved, and for communication with citizens and other stakeholders.

Monitoring and evaluation have complementary goals

A robust policy monitoring system provides policymakers with the tools and evidence needed to detect bottlenecks in policy implementation, adjust policy performance, and communicate policy outcomes to citizens. For example, OECD and non-OECD countries have developed their policy monitoring practices with a view towards accountability and performance management, but also to communicate with citizens and improve the achievement of development goals (see Box 3.7).

The practice of monitoring public policies has developed since the 1990s in OECD countries with a view to making public management more accountable and efficient.

In the United States, the Government Performance and Result Act of 1993, strengthened in 2010, aims to improve government performance management. In particular, it requires federal agencies to engage in a performance approach by measuring and reporting their results through the development of multi-year strategic plans, an annual performance plan and an annual performance report.

In Canada, a modern comptrollership initiative has been underway since 1997. A new management accountability framework (cadre de gestion pour la reddition de comptes - CRG) was thus adopted in 2003, and a results-based management policy has been implemented since 2016 through a results-based budget allocation.

This trend has been complemented by a desire to better communicate and showcase government results.

In the United Kingdom, this led to the creation in 2001 of a Delivery Unit attached to the Prime Minister, in a framework of citizen dissatisfaction with the quality of their public services. This mechanism was set up to monitor and measure the implementation of reforms assigned to ministries and agencies. It is an effective tool for communication, transparency and accountability in government.

In Colombia, the national system for the evaluation of management and results (SINERGIA) aims to improve the effectiveness of the formulation and implementation of the national development plan. This mechanism includes a monitoring component based on the use of a system of indicators associated with the Plan's goals at the strategic, sectoral and management levels. This monitoring is applied at the central level but also at the territorial and decentralised levels, in order to provide global information on the performance of public policies in the country.

Many non-member countries have also adopted a policy monitoring framework to better monitor the performance of their policy instruments.

In South Africa, the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation aims to empower officials and managers, improve public policy planning and get departments working towards common goals. This system is based on performance targets for each ministry and a system of indicators associated with government performance targets.

Source: Based on information from the United States Office of Management and Budget, the Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada, the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation of the Republic of South Africa (OECD, 2018[30]), the Public Governance Review of Paraguay (Lafuente and Gonzalez, 2018[31]) and Do Delivery Units deliver?

Similarly, the evaluation of public policies is an essential governance tool to ensure that reforms carried out contribute to the improvement of public services and the well-being of citizens. For this purpose, evaluations aim to objectively measure the extent to which the results observed are attributable to the public policies implemented. In this way, the evaluation contributes to the dissemination of a culture of results within the administration, to the accountability of public decision-makers and to the achievement of long-term government goals (OECD, 2020[29]).

The institutional framework for monitoring and evaluation (M&E) is fragmented

A strong institutional framework for policy monitoring and evaluation enables the formalisation and systematisation of practices that are isolated and uncoordinated in their absence. The institutionalisation of the M&E system accordingly aims to establish standards and guidelines for methods and practices (Gaarder and Briceño, 2010[32]) and can provide effective incentives for the conduct of quality assessments and the systematic collection of performance monitoring data (OECD, 2020[29]). Although there is no single approach in the way countries have institutionalised their M&E practices, a strong institutional framework should include:

One or more clear and comprehensive definitions, anchored in a formal framework. These definitions must clearly distinguish between monitoring and evaluation, which are complementary but distinct practices, and specify the policies involved.

A practice anchored in a political and statutory framework, either at a specific level of the hierarchy of norms (law, regulation, etc.), or through strategic documents or dedicated guidelines.

Identification of the institutional players responsible for overseeing or conducting monitoring and evaluation, as well as their resources and mandates.

Macro-level guidance on "who, when and how" monitoring and evaluation of public policies should be carried out.

In Haiti, there is no definition of monitoring or evaluation that is shared by the different components of government

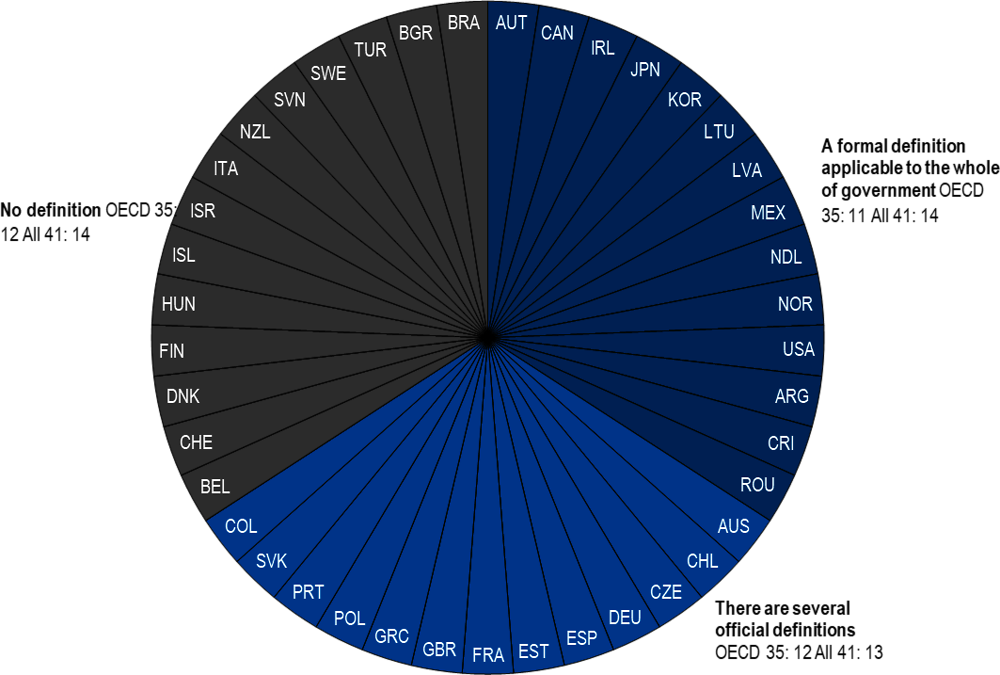

According to data collected by the OECD, (OECD, 2020[29]) the majority of OECD countries (23 out of 25) have one (11 countries) or more (12 countries) official definitions of policy evaluation (see Figure 3.1). In some countries, this definition is anchored in a statutory or regulatory framework. This is the case in Japan, where the government law on the evaluation of public policies, provides a definition of evaluation (Law No. 86 of 2001), while in Argentina, Decree 292/2018, designates the players responsible for developing the evaluation of social policies and programmes (Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica, 2018[33]). Other countries define evaluation in methodological guides, as is the case in Colombia.

In Haiti, there is no such shared definition. However, the adoption of a clear and precise definition is an important step in the institutionalisation of evaluation. Indeed, this enables a common understanding of the issues, goals and tools to be mobilised to implement the evaluation, not only within the public sector, but also between all the players of the system, such as the TFPs and civil society organisations (CSO).

For example, while the content of evaluation definitions could vary from country to country, a few key concepts are found in most of the definitions analysed by the OECD (OECD, 2020[29]), namely

Evaluation criteria (impact, effectiveness, efficiency, etc.),

The type of public policies involved (projects, programmes, plans, etc.),

The characteristics of the evaluation, which include the quality criteria of the evaluation, the type of measures expected, the method of conduct and the players involved.

Haiti's monitoring and evaluation system forms part of a clear institutional landscape that primarily involves the MPCE and sector ministries

The Decree of 17 May 2005 on the organisation of the central government administration sets out the general regulatory framework for the national system for monitoring and evaluating public policies. Several players at the level of the centre of government (CoG) thus play an important coordinating and promotional role in this area. These are:

The Office of Human Resources Management (OMRH) is responsible, in particular, for "ensuring the performance of the public service system through regulation and evaluation". This responsibility is entrusted to it by Article 113 of the 2005 Decree. However, it is limited to the monitoring and evaluation of measures related to the public service.

The Public Policy Coordination and Monitoring Unit (cellule de coordination et de suivi des politiques publiques - CCSPP), which "monitors and evaluates government action and contributes to the preparation of strategic reflection files, primarily on issues relating to good governance". This unit, attached to the Prime Minister, was nevertheless disbanded in 2016 due to potential duplication with the MPCE mandate.

The Ministry of Planning and External Cooperation (Ministère de la Planification et de la Coopération Externe - MPCE) is responsible for "monitoring and evaluating the plans and programmes developed by the Ministry". This planning coordination role is confirmed by the Decree of 2 February 2016 organising the MPCE (Gouvernement d'Haiti, 2016[34]). The MPCE is accordingly the main actor for coordinating and promoting monitoring and evaluation within government.

In addition to these new players at the centre of government, line ministries are responsible for monitoring and evaluating sectoral public policies, through the study and programming units (UEP) (Article 63 of the 2005 Decree). The box below (Box 3.8) provides more information on how UEPs work.

The UEPs are central State services whose powers are defined in Article 63 of the Decree of 17 May 2005 on the organisation of the central State administration.

The UEPs serve as the main point of contact for the Ministry of Planning and Cooperation within each sectoral ministry. They are responsible for monitoring and evaluating sectoral public policies on behalf of the MPCE. The capacities of these units vary considerably from one department to another. There is currently no consistent competency framework for personnel working in these units.

Source: Decree of 2 February 2016 on the organisation of the Ministry of Planning and External Cooperation; Decree of 17 May 2005 on the organisation of the central administration.

Finally, in Haiti, the TFPs play an important role in the monitoring and evaluation of public policies. However, the initiatives carried out by the TFPs in this area do not seem to contribute to the Haitian national system of M&E and accordingly, ultimately, to the improvement of the use of evidence in national policy-making.

There is a separate monitoring system for the PME-2023

In Haiti, in addition to the mandates of these players, there are specific systems for monitoring the government's priority policies, formalised in the PSDH and the PME-2023. This means that a specific governance is created to ensure the monitoring and evaluation of the PME-2023, composed of the following players

A strategic steering committee chaired by the Prime Minister and composed of the sectoral ministries and the OMRH, which ensures the steering of the PME-2023 at the highest political level;

An operational steering committee, chaired by the OMRH, and composed of the sectoral and sub-sectoral committees of the ministries, which develops the monitoring processes in the ministries and evaluates the results of the implementation;

Sectoral committees in each department, composed of Directors General and UEPs, which develop a monitoring plan and communicate internally and externally on progress.

There is no inter-ministerial legal or policy framework for monitoring and evaluation in Haiti

A majority of the countries surveyed by the OECD (29 countries, including 23 OECD countries) have developed a legal framework for whole-of-government evaluation. The fact that more than two-thirds of the countries surveyed have developed such a legal framework shows the importance attached to systematising this practice. However, OECD countries have anchored evaluation at several levels in the hierarchy of standards. The OECD (2018) survey indeed shows that evaluation can be recognised at the highest level of the hierarchy of norms, in a law or even in the constitution, but it is not a necessity.

In France, for example, the practice of public policy evaluation is affirmed at the constitutional (Article 47-2 on the mandate of the Court of Auditors), legal and regulatory levels (see Box 3.9).

France has established a statutory framework for policy evaluation integrated at three different levels: the Constitution, primary legislation and secondary legislation.

At the constitutional level, Article 47-2 entrusts the supreme audit institution, the Court of Auditors, with the task of assisting Parliament and the Government in the evaluation of public policies. The results are made available to government and citizens through the publication of evaluations. Evaluation activities are also defined in Articles 39 and 48 of the Constitution.

Regarding primary legislation, Articles 8, 11 and 12 of Organic Law No. 2009-403 on the application of Article 34-1 of the Constitution require that legislative proposals be subject to an ex ante impact assessment. The results of the assessment are then attached to the legislative proposal as soon as they are sent to the Supreme Administrative Court (the Council of State).

At the level of secondary legislation, Article 8 of Decree No. 2015-510 provides that any draft law affecting the missions and organisation of the State's deconcentrated services must be the subject of an impact study. The main goal is to verify the consistency between the goals pursued by the proposal and the resources allocated to the decentralised services.

In addition, France has a number of circulars from the Prime Minister on evaluation. On 12 October 2015, the circular dealt with the assessment of standards, and in May 2016 with the impact assessment of new bills and regulatory texts.

Source: OECD Study (2018), Constitution of the Fifth Republic, respective Articles on Légifrance (https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr).

Similarly, several OECD countries have developed a transversal statutory or regulatory framework to organise performance monitoring. This is the case in the United States under the Government Performance and Results Modernisation Act.

In Haiti, there is no coherent statutory framework underpinning the system of evaluation and monitoring of public policies across government2. In addition, as the example of the CPPCC shows, some of the public administration decrees that anchor the institutional mandate of monitoring and evaluation players are not up to date.

There is no general or specific guidance for conducting monitoring or evaluation

Other countries have chosen to place these practices within a policy framework. A policy framework is generally a document or set of documents that provide strategic direction, principles and a plan of action for government on a specific sector or issue. Public policy frameworks could or could not include legislative acts, as well as ministerial acts in the form of guidelines, for example (OECD, 2020[29]). The existence of such a policy framework demonstrates the importance that governments attach to these practices as vehicles for improving public policy and, ultimately, development. These policy frameworks make it possible, above all, to define the goals and concrete methods for implementing monitoring or evaluation: who are the players, what policies are to be evaluated or monitored, and what is the timetable for implementing M&E.

Therefore, like half of the countries surveyed by the OECD (21 in total, including 17 OECD member countries), Benin has developed such a public policy framework for whole-of-government evaluation. The following box (Box 3.10) provides more information on this framework.

Benin has rooted the practice of evaluation in a solid policy framework through the National Evaluation Policy 2012-2021 (NEP (République du Bénin, 2012[35])) and more recently the National Evaluation Methodology Guide (Bureau de l’Évaluation des Politiques Publiques et de l’Analyse de l’Action Gouvernementale, 2017[36]). This NEP sets out an overall framework for the purpose and goals of evaluations, the standards and principles to be followed in their conduct, and the measures available to implement them. In this sense, the NEP 2012-2021 institutionalises the practice of evaluation by contributing to the development of formal, systematic and aligned evaluative practices in terms of methodology and use of results across government (Gaarder and Briceño, 2010[32]).

Sources: in the text.

The latest PSDH implementation report indicates that the Haitian government intended to develop "methodological documents [on] the results framework for monitoring the PSDH and public policies and the ODD". However, these initiatives have not been successful due to the economic and social difficulties faced by the country in recent years (Gouvernement d'Haïti, 2020[3]). There is a Manual of Procedures on the Management of Public Investments (Government of Haiti, 2014), which applies exclusively to public investment projects and focuses on a summary monitoring of the financial and physical implementation of projects.

The terms (players, methodology and sequencing) and tools for monitoring are still unclear, which can significantly constrain the effectiveness of performance monitoring. There is no methodological document organising whole-of-government monitoring. This means that if the governance of the monitoring of the PME-2023 is explained in this document, its exact methodology and all the players involved are not specified. Indeed, if the committees presented above are mandated to validate the monitoring reports (called "evaluation" in the PME-2023, but more likely monitoring reports) and to take concerted decisions on the way forward, they do not seem to be involved as such in several key stages of the monitoring value chain: data collection and updating of indicators, consolidation of progress scorecards and proposal of scenarios concerning the way forward In the event of implementation difficulties. In other words, they are decision-making bodies, which are an indispensable part of a performance monitoring system, but which cannot function without their operational or administrative counterparts.

Laying the foundations for a robust public policy evaluation system by institutionalising practice

A system can be defined as "a set of elements linked together by a dynamic that produces an effect, creates a new system or influences its elements" (OECD, 2017[37]). More specifically, a public policy evaluation system can be defined as "a system in which evaluation is a normal part of the life cycle of public policies and programmes, conducted in a systematic and rigorous manner, and whose results are used in decision-making processes and made available to the public" (Lázaro, 2015[38]).

To establish such a system, the first step is for governments to institutionalise the practice of evaluation in order to give an explicit mandate to public players (see Box 3.11).

A good public policy evaluation system is developed through the following three dimensions:

Institutionalisation: refers to the process of integrating evaluative practices with more formal and systematic approaches. This could include establishing a system of evaluation in government settings through specific policies or strategies (Lázaro, 2015[38]; Gaarder and Briceño, 2010[32]).

Quality: refers to policy evaluations that are technically rigorous and well governed, i.e., independent and responsive to the decision-making process (Picciotto, 2013[39]).

Use: occurs when evaluation results lead to a better understanding or a change in the design of the evaluation topic, or when evaluation recommendations inform decision-making and lead to a change in the evaluation topic.

Source: Lázaro (2015[38]), Gaarder and Briceño (2010[32]), Ledermann (2012[40]), and Picciotto (2013[39]).

Providing a statutory framework and general guidance for the conduct of the evaluation

The Haitian government could benefit from the adoption of a law defining a framework for the implementation of monitoring and evaluation throughout the government, in order to build political consensus, beyond electoral cycles, on the importance of M&E for the country (OECD, 2020[29]). The relevance of this law is heightened in a period of electoral transition.

In addition, the Haitian government could benefit from the adoption of a directive or methodological guide to clarify the role of players in M&E, as well as to provide guidance at the global level on "by whom, when and how" monitoring and evaluation of public policies should be carried out. This type of guidance is useful for ensuring that departmental resources are focused on monitoring and evaluating high-stakes social and economic policies, as well as for planning the human and financial resources that will be devoted to the M&E.

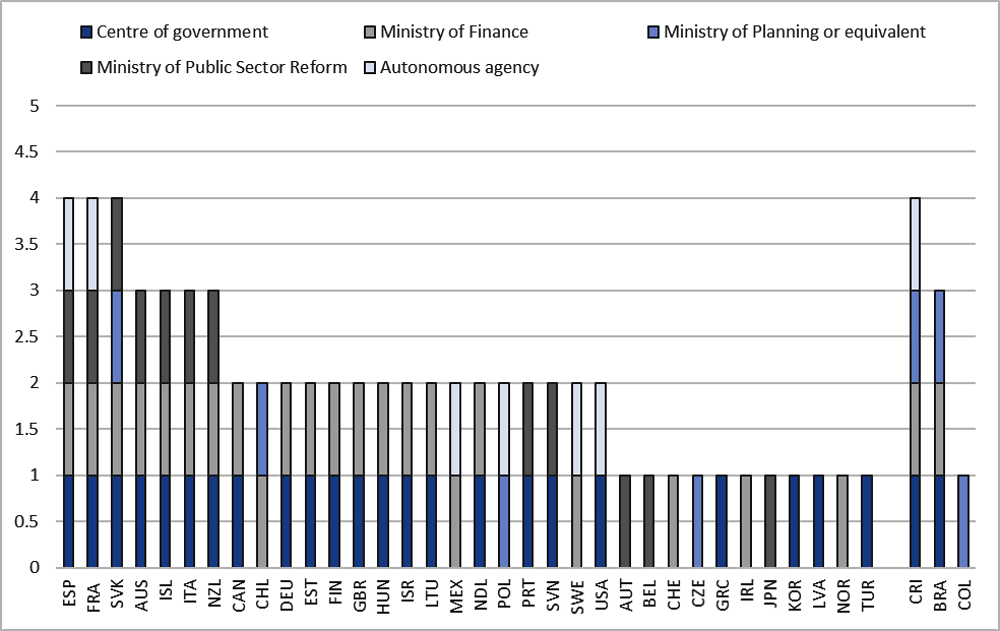

Streamlining the functioning of the players and strengthening the role of the centre of government in evaluation

In the majority of countries surveyed by the OECD, the centre of government3 (CdG) has a major role to play in coordinating the evaluation practices of ministries. Indeed, the various structures of the centre of government are strategically positioned to disseminate a culture of evaluation throughout the administration, as well as to coordinate the action of the various ministries, agencies and sectoral institutions (OECD, 2020[29]). In addition, the coordination capacities of the CdG are all the more important as governments will have to assess the impact of economic aid and health policies (Figure 3.2).