Chapter 4. Rethinking public institutions in the digital era

Rising levels of mistrust in public institutions and dissatisfaction with public services in Latin America and the Caribbean illustrate a weakening social contract, which can be further eroded by the impact of coronavirus (Covid-19). The digital transformation represents a unique opportunity to improve the function and service quality of public institutions. While emerging institutional risks must be taken into account, moving towards digital governments can help public institutions become more trustworthy, efficient, inclusive and innovative. The digital transformation affects a range of public policies, which need to be included in a comprehensive framework, such as national development strategies, to guarantee coherence and synergies and make the most of new technologies. Connecting digital strategies to national development plans is crucial to align digitalisation efforts with broader, long-term development objectives.

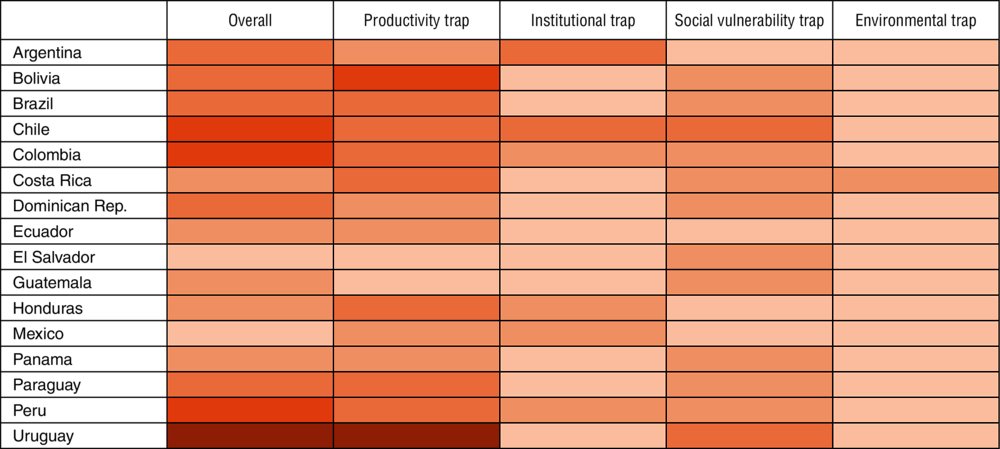

The expansion of the middle class in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) since the beginning of the century has come with rising social aspirations. The coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic is likely to increase demands for stronger public institutions and better quality public services. Institutions are failing to respond to these rising aspirations, despite improvements in public governance in past years. Across most LAC countries, distrust and low satisfaction are deepening, and social discontent is growing. Citizens see less value in fulfilling social obligations, such as paying taxes, as illustrated by low levels of tax morale, undermining revenue to finance better public services and respond to social demands (OECD, 2019a). This creates a vicious circle in LAC that can be understood as an “institutional trap”, which involves a circular, self-reinforcing dynamic that limits capacity to transition to greater development (OECD et al., 2019). The extent to which the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic deepens social discontent and changes citizens’ aspirations is yet to be seen, but public institutions have been under unprecedented pressure and will need to find ways to respond to evolving social demands and extraordinary policy challenges.

In this context, the digital transformation presents new challenges, but also significant opportunities to strengthen the social contract between citizens and the state, and better respond to rapidly changing public demands.

First, the digital transformation has resulted in rising expectations on the part of digital citizens regarding the quality of public services and the integrity, transparency and responsiveness of public institutions. The exponential growth of smartphones and daily streaming of Big Data are changing the way Latin Americans live, especially in urban areas. The growing middle class and young citizens are the most digitally savvy and demanding (Santiso, 2017). Provision by top private digital service providers of seamless user experiences creates greater demands from citizens, representing a challenge for the public sector. Without designing and implementing appropriate public policies, unmet expectations could reinforce the divide between citizens and public institutions.

Second, technological progress demands innovative policy responses to address new regulatory challenges. Regulating the digital transformation to mitigate its harmful impacts and promote its benefits for all is a key aspect of the policy agenda. Regulations are crucial to safeguarding public trust in the context of the digital transformation. Emerging policy domains, including digital security, data privacy, protection and governance, and ethical considerations, are increasingly relevant.

Third, new technologies and data analytics can transform governments. Responding to emerging challenges and embracing new opportunities require a redesign of public institutions. Latin American governments have the potential to become more trustworthy, efficient, inclusive and innovative by tapping into the new possibilities offered by technological progress. Doing so could help restore confidence in public institutions and improve the quality and reach of public services.

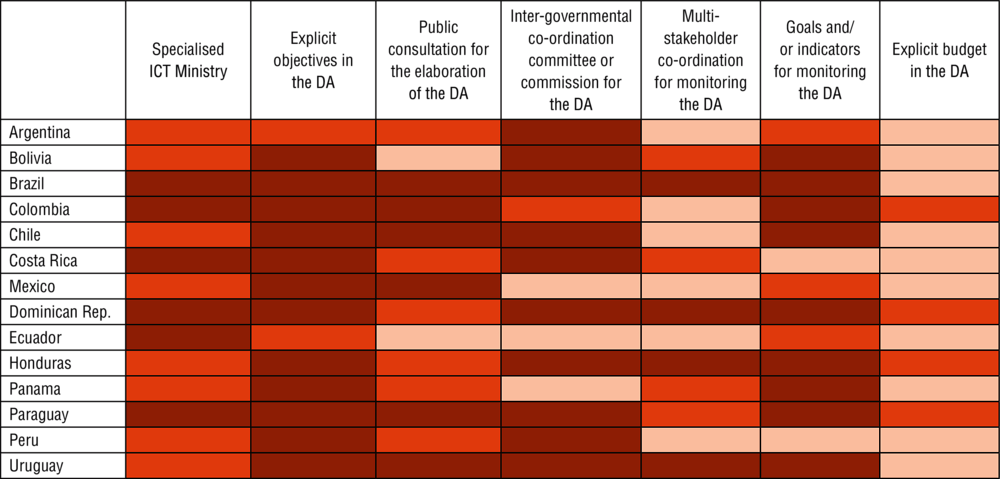

Fourth, making the most of the digital transformation requires an ambitious agenda and a co-ordinated and comprehensive approach. LAC governments need to mainstream the digital transformation in national development plans (NDPs) and digital agendas/strategies (DAs). On the other hand, digital technologies are also part of the solution. Digital tools (e.g. videoconferences, online consultations) facilitate multi-stakeholder involvement in the construction of national development strategies, thus setting the basis for a truly inclusive new social contract.

Fifth, the digital economy is an extension of the material economy. Dramatic technology-driven changes in patterns of consumption and production require policy design and regulatory frameworks that create the conditions for governments, consumers, producers and citizens to enlist new capabilities, generate value and become relevant actors in the digital economy (ECLAC, 2016).

The coronavirus (Covid-19) crisis makes the digital transformation of governments more urgent and a top priority of NDPs. Closure of public administration buildings has revealed the importance of end-to-end digital services and interoperable systems. While data have become key inputs, especially for public health, they have also raised the relevance of digital security and data protection policies.

The three sections of this chapter analyse the challenges and opportunities the digital transformation presents for public institutions, and consider avenues to rethink and adapt institutional frameworks for the digital era. The first section, “Governing the digital transformation”, describes the main challenges and opportunities of the digital transformation regarding public trust, including adequate digital security, data protection and governance, and new ethical considerations. The second, “The digital transformation of governments”, analyses how digital technologies can promote more trustworthy, efficient, inclusive and innovative states. The final section, “The digital agenda in national development strategies”, analyses how LAC countries have included the digital transformation in NDPs and DAs, and how their priorities address the region’s development traps.

The profound transformations brought about by technological progress challenge the adequacy of the current national and international institutional set-up. New risks and opportunities lie ahead; the rules of the game must adapt to make the digital transformation a driver of progress and greater well-being for all. This section considers the regulatory aspects shaping the digital transformation and areas that affect citizen trust in digital technologies, including digital security, data protection and governance, and new ethical considerations, for instance concerning artificial intelligence (AI) or misinformation and fake news. It also deals with what can be defined as the evolution of human rights in the digital era, i.e. “digital rights”, such as the right to personal data protection, transparency, information on AI and the option to opt out (OECD, 2019b). Further digital rights, such as digital communication with governments, application of the once-only principle, open data and proactive service delivery are analysed in the following section.

Regulatory frameworks must support a fair and equitable digital transformation

Governments face new regulatory challenges in ensuring that the opportunities and benefits of the digital transformation can be realised by all (OECD, 2019c). Regulatory frameworks must strike a balance between fostering the digital transformation and preserving secure and affordable access to digital technologies. Five steps can help achieve this objective.

First, regulatory frameworks must promote competition and investment arising from the increasing convergence of networks and services in the digital economy (e.g. seamless provision of digital services across networks). Competition is key to promoting innovation and enabling all consumers to benefit at competitive rates. Independent agencies are needed to address dominance issues or impose wholesale regulations when necessary to lower barriers to new entrants (OECD, 2019c). Some reforms in LAC, such as Mexico’s 2013 telecommunication reform, highlight the importance of strong competition, strong regulatory frameworks and support for investment, particularly in remote and rural areas (OECD, 2017a; OECD, 2019c). An independent regulator is essential to public confidence in the integrity of regulatory decisions (OECD, 2019d, 2014a).

Second, a stable and predictable regulatory framework fosters long-term investment in communication infrastructure and digital innovation. In a sector where return on investment is often measured in decades, guaranteeing regulatory stability, transparency and legal certainty helps firms prepare business plans and ultimately facilitates investment (OECD, 2012). Strong institutions boost investor confidence and encourage investment in communication infrastructure.

Third, the regulatory framework must help protect consumers, particularly in online transactions involving personal data. Lack of adequate protection may deter e-commerce and uptake of new products. Fostering access to data and data portability, as well as issues related to data ownership, should be a priority of regulations, ensuring that accumulation of data from incumbents does not create barriers to entry for newcomers, thereby slowing down innovation and reducing competition (OECD, 2019c).

Fourth, innovation-friendly regulations enable the growth of new industries and digitally intensive firms. Digital innovation frequently takes place outside existing frameworks. Regulations should therefore be flexible: accomplishing the legitimate goals of regulation without discouraging innovation and missing out on the benefits of the digital transformation. One policy response, “regulatory sandboxes”, provides flexibility in the form of a limited regulatory waiver, usually to facilitate experimentation and testing (OECD, 2019c). Colombia’s digital transformation and AI strategy proposed “regulatory sandbeaches” (Republic of Colombia, 2019). Encouraging and realising innovation requires technologically neutral regulations that guarantee fair competition among developing technologies (OECD, 2003).

Fifth, in establishing new regulations, stakeholder responsibilities must be clear, avoiding overlap and giving institutions tools to enforce decisions. There should be a clear separation between policy formulation and regulatory functions. Implementing systematic measurement frameworks to monitor the growth of broadband and digital services is critical to inform policy and regulatory decisions. Stakeholder involvement and peer and third-party independent reviews should be encouraged to identify improvements to the regulatory framework. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) peer reviews of telecommunication markets in Colombia (OECD, 2014b) and Mexico are examples of this approach (OECD, 2012; OECD, 2017a).

At the international level, there is a need to update multilateral digital taxation and trade rules. The digitalisation of the economy brings about new tax challenges. There is ongoing global negotiation within the OECD to reach a global agreement so that multinational enterprises conducting sustained and significant business in places where they may not have a physical presence – a typical feature of digital firms – can be taxed in such jurisdictions (see Chapter 5). Cross-border data flows are another relevant area. Data underpin the digital transformation and affect the trade environment. Governments increasingly seek to regulate cross-border data transfer to protect privacy when data are stored or processed abroad or require data to be stored locally (OECD, 2019c).

At the regional level, in many instances, regulatory frameworks in LAC continue to operate in silos. Regional co-operation arrangements, sharing of regulatory experiences, deployment of regional infrastructures, cross-border data flows and lowering the cost of international connectivity and roaming should be encouraged (OECD, 2019c) (see Chapter 5).

Digital security is key to make the digital transformation work for all

Digital security incidents risk causing social and economic harm if not addressed. They can cause disruption of operations and essential public services, direct financial loss, lawsuits, reputational damage, loss of competitiveness (e.g. through the disclosure of trade secrets), privacy harm and consumer distrust (OECD, 2015a).1

Digital security risks increased during the coronavirus (Covid-19) crisis. Cybercriminals count on the likelihood that individuals and organisations more easily fall for scams or pay ransoms in periods of stress, in particular those lacking good digital security practices or facing organisational disruptions. These growing risks strengthen the need for sufficient safeguards to protect sensitive sectors from digital security incidents. As critical infrastructure and essential services sectors – both private and public – become increasingly digital dependent, the need for comprehensive and holistic national strategies for digital security, developed in consultation with all stakeholders, becomes more urgent.

Recent examples highlight the importance of digital security incidents from a socio-economic perspective. The 2017 NotPetya digital security attack, which affected several countries and global companies, caused the temporary shutdown of the production, research and commercial operations of the big pharma enterprise Merck. In November 2019, ransomware forced Pemex (state-owned Mexican Petroleum) to shut down computers across Mexico; USD 5 million in bitcoin were demanded to end the attack. While the attack reportedly only affected the payments system, it could have endangered the entire country’s energy security (Barrera and Satter, 2019). These examples show that digital security risk should be treated as an economic and social challenge, rather than only as a specific technical or national security issue.

Most LAC countries are moving towards a strategic, long-term vision for digital security (OECD/IDB, 2016). In 2019, 13 Latin American countries had a national digital security strategy (IDB/OEA, 2020), but policies had a limited understanding of the economic and social dimensions of digital security, and tended to focus on criminal and technical aspects or on national security. They also showed a limited level of stakeholder co-ordination across government and business sectors. Such co-ordination is an important aspect of the digital transformation, as critical services across finance, energy and transport sectors are increasingly offered by start-ups that provide innovative payment systems or are subcontracted to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in essential service value chains. Ensuring sufficient digital security risk management across all sectors and actors, including SMEs, makes co-operation and multi-stakeholder dialogue all the more important (OECD, 2019c).

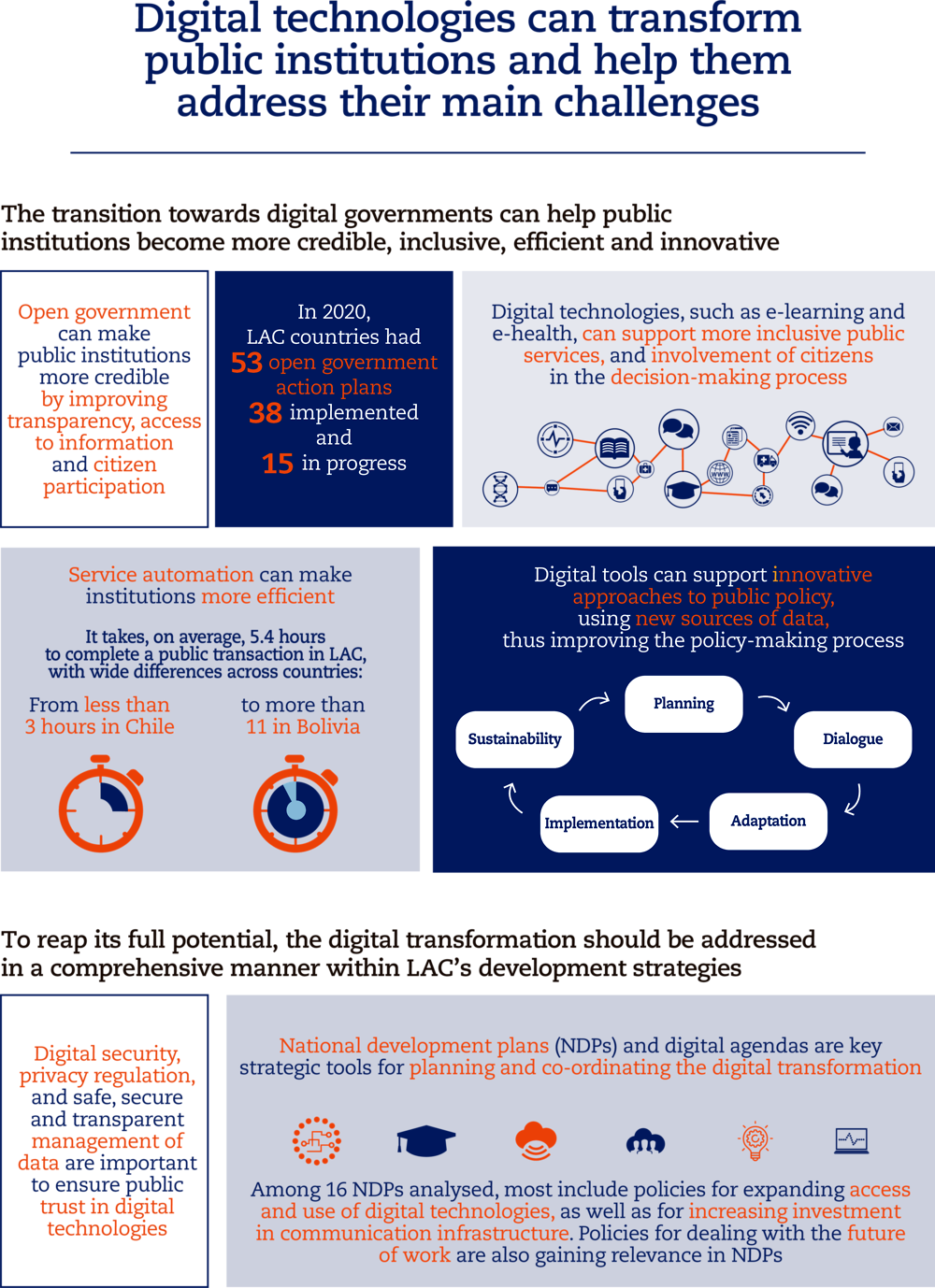

The greatest efforts related to digital security in LAC have taken place on the legal front, but other key dimensions are still lagging. LAC shows the lowest commitment to digital security after Africa, according to the United Nations (UN) Global Cybersecurity Index (ITU, 2019), which measures five dimensions: legal, technical, organisational, capacity building and international co-operation. The index combines 25 indicators in a single measure, ranging from 0 (no cybersecurity efforts) to 1. Uruguay alone shows a relatively high level of cybersecurity, scoring 0.68 and ranking 51 of 175 countries. The rest of the region scores medium or low. Progress in legislation has been more significant: 30 countries have cybercrime legislation and cybersecurity regulations, and 10 have norms for containing mass emails (spam). Regional efforts have also concentrated on developing digital security strategies, but efforts in other dimensions lag (Figure 4.1).

Data are increasingly relevant assets: Privacy, governance and value

The digital economy is characterised by a growing number of entities collecting vast amounts of personal data. These include online retailers, digital platforms, financial service providers and governments. This data-rich environment, together with the emergence of more sophisticated tools for analysis, makes it possible to infer sensitive information. Misuse of this information may undermine individuals’ personal privacy, including their autonomy, equality and free speech (Buenadicha Sánchez et al., 2019; OECD, 2016a).

During the coronavirus (Covid-19) crisis, many governments turned to digital technologies and advanced analytics (e.g. contact tracing, biometrics and geolocated data from mobile apps) to collect, process and share data for effective front-line responses to the spread. These technologies can be useful, as they provide critical information to improve the effectiveness of policies. However, left unchecked, they can also be used for extensive collection and sharing of personal data, mass surveillance, limiting individual freedoms and challenging democratic governance. Few LAC countries have frameworks to support these extraordinary measures in ways that are fast, secure, trustworthy, scalable and in compliance with existing privacy and data protection regulations. Privacy enforcement authorities (PEAs) play a key role in applying new or existing privacy and data protection frameworks. For instance, Argentina’s PEA, the National Access to Public Information Agency, released general guidance about the application of privacy and data protection laws in the crisis for data controllers and processors. Measures adopted should be proportionate and limited to the duration of the emergency (OECD, 2020a, 2020b).

Incorporating ethical reflections on data management and use in regulations and codes of conduct is therefore a key policy issue. Ethical management of data encompasses: 1) respect for the data and privacy of individuals and organisations; 2) respect for the right to anonymity; 3) the need for informed consent in data collection (informing as to the purpose and ensuring consent to use of data for this purpose); and 4) a general need for transparency (Brito, 2017; Buenadicha Sánchez et al., 2019; Hand, 2018; Mittelstadt and Floridi, 2016). The OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, updated in 2013, continue to represent international consensus on general guidance concerning the collection and management of personal information (OECD, 2013a).

Regulations for data protection have evolved significantly recently, bringing important changes in LAC. The European Union (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has strongly influenced regulatory frameworks in LAC. It sets high standards for regulating the digitalisation of the economy. It includes any organisation that collects, controls, processes or uses the personal data of data subjects who are in the EU, regardless of the organisation’s location (see Chapter 5). In August 2018, Brazil passed the Lei Geral de Proteção de Dados, a new general data protection law that will come into force in 2021. Chile’s new framework is under legislative discussion. Argentina and Uruguay have updated legislation for compliance with the GDPR.

The United States (US) data protection privileges privacy and data security, and some US framework rules apply to entities outside its territory handling the personal data of American citizens. The Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation Forum Privacy Framework, which focuses on avoiding barriers to trade information flows in LAC, is another important reference. It has been influential in developing data protection frameworks in Mexico, Colombia and Peru (Lehuedé, 2019).

Progress in regulatory frameworks for data protection in LAC is mixed. Most countries have data protection frameworks in place. Despite common features, these vary significantly (Table 4.1). Most differences may be explained by the date of adoption and, to some degree, the influence of the different regulatory frameworks mentioned above. In turn, the adoption of uncoordinated national rules is one of the main challenges to the transfer of personal data between jurisdictions. The resulting web of permissions, consents and restrictions could affect economic activity. International harmonisation initiatives in the region should be supported (Lehuedé, 2019). For instance, the European Commission’s 2020 “Shaping Europe’s digital future” envisions the creation of a common market for data (European Commission, 2020).

Regulation models also influence adequacy schemes, which regulate authorisations for international transfers of personal data. The European Commission determines whether a non-EU country offers adequate data protection.2 Currently, Argentina and Uruguay in LAC provide an “adequate level of data protection” for cross-border data transfers (Table 4.2). In those cases, transfers of personal data to data processors are allowed, and data controllers and processors share liabilities for data breaches (European Commission, 2019a).

More accurate and granular data are feeding into the world of research, demanding additional privacy and protection precautions. New forms of data, especially personal data from Internet usage and commercial transaction information, tracking systems and Internet of things (IoT) data and government information, have the potential to revolutionise research and provide new social and economic insights. However, they come with new ethical challenges and a responsibility to ensure public confidence in their correct use for research (Metcalf and Crawford, 2016; Mittelstadt and Floridi, 2016). In 2013, the OECD recommended the development of a code of conduct framework covering the use for research of new forms of personal data. This recommendation stressed the need to strike a balance between the social value of research and the protection of individual well-being and rights, including to privacy (OECD, 2016a). The European Union requires organisations and universities applying for public research and development (R&D) financing under Horizon 2020 to address 11 ethical concerns and give explanations and monitoring guarantees for the most sensitive projects (European Commission, 2019b; Buenadicha Sánchez et al., 2019). Mexico has a checklist to help scientists guarantee ethical protocols and the Guía nacional para la integración y el funcionamiento de los comités de ética en investigación (National guide for the integration and functioning of ethics committees in research).

Defining data responsibility and ownership is a complex and critical issue. While intellectual property rights protection can incentivise R&D investment, it risks restricting access to data derived from publicly funded research. While challenging, disentangling data types may be helpful for regulatory purposes.

Data access and data sharing are estimated to generate social and economic benefits worth between 0.1% and 1.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the case of public-sector data, and between 1% and 2.5% of GDP (up to 4% in some studies) when including private-sector data. The estimated magnitude of the effects depends on the scope and degree of openness of the data (OECD, 2019e). Business models relying on personal data as key inputs are increasingly common (OECD, 2013b). Considering data have become the main factors of production in the digital economy and thus competitive assets, regulation should ensure that data are not used and held in anti-competitive ways, and allow actors fair access to data.

The digital transformation raises new ethical issues

Artificial intelligence needs to be fair, secure and transparent

As AI applications are adopted around the world, their use can raise questions and challenges related to human values, fairness, human determination, privacy, safety and accountability, among others. This underlines the need to progress towards more robust, safe, secure and transparent AI systems with clear accountability mechanisms (OECD, 2019f). Ethical considerations should acknowledge the potential for discriminatory biases in the functioning of modern technologies. This is especially important given the increasing use of AI and machine learning in decision making in public institutions, for example for the provision of public services. Data can be imperfect as a result of flawed decisions by those collecting them. They can also be insufficient, erroneous, biased or outdated (Buenadicha Sánchez et al., 2019). Job-matching algorithms may reproduce historical inequities and prejudices against skin colour or gender, for instance. An experiment found that women were less likely than men to receive Google Ad Services ads for high-paying jobs. The algorithm targeting ads may be trained on data in which women have lower paying jobs (Datta, Tschantz and Datta, 2015). Lack of diversity in the tech sector may perpetuate these biases: LinkedIn and World Economic Forum (WEF) information suggests that only 22% of AI professionals are women (UNDP, 2019).

Transparency about the use of AI and how AI systems operate is therefore key. Regulation in this respect has progressed recently, with several LAC countries adhering to international standards. The GDPR includes the right against automatised profiling, which allows data subjects to ask to be excluded from automated decision-making processes. It also includes the right to explicability, i.e. individuals affected by an algorithmic decision have the right to be informed of the logic applied and the importance and consequences of the logic on the individual. OECD countries adopted the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence (OECD AI Principles) in May 2019 to promote innovative, trustworthy AI that respects human rights and democratic values (OECD, 2019f). The Principles complement existing OECD standards for privacy, digital security risk management and responsible business conduct. In LAC, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru adhere to the Principles. The OECD also launched an AI Policy Observatory in February 2020 (Box 4.1).

The OECD AI Policy Observatory aims to help countries encourage, nurture and monitor the responsible development of trustworthy AI systems for the benefit of society. Building on the OECD AI Principles, the Observatory combines resources from across OECD countries with those of partners from all stakeholder groups to facilitate dialogue and provide multidisciplinary, evidence-based policy analysis on AI.

The Observatory provides resources on AI public policy topics, AI policies and initiatives, trends and data, and practical guidance on implementing the Principles. Countries and other stakeholders share and update a live database of AI policies and initiatives, including AI policies from seven LAC countries, enabling interactive comparison of key elements. The database is a centre for policy-oriented evidence, debate and guidance for governments, supported by strong partnerships with a wide spectrum of external actors (OECD, 2020c).

Beyond transparency, policies that promote trustworthy AI systems include those that: encourage investment in responsible AI R&D; enable a digital ecosystem where privacy is not compromised by broader access to data; enable SMEs to thrive; support competition, while safeguarding intellectual property; and equip people with the skills necessary to facilitate transitions as jobs evolve (OECD, 2019f). Beyond helping implement OECD AI Principles, the OECD Network of Experts on AI, a multi-stakeholder, multidisciplinary group, informs the development of a repository of non-government stakeholder and intergovernmental initiatives, including private standards, voluntary programmes, professional guidelines or codes of conduct, best practices, principles, public-private partnerships and certification programmes.

More than 20 countries have national AI strategies, and LAC is catching up. Mexico was among the first ten countries, and the first in LAC, to develop an AI strategy in 2018. Colombia’s 2019 National Policy on Digital Transformation and AI commits to creating an AI market, with priority given to market-creating innovations, an ethical framework and level of experimentation. In Brazil, online public consultations are expected to deliver inputs for the development of a Brazilian AI Strategy aimed at maximising benefits for the country. Argentina is developing a national plan to foster AI development in line with the ethical and legal principles framed in the Argentina Digital Agenda 2030 and as one of the national challenges in the Innovative Argentina Strategy 2030. Chile’s Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge and Innovation has a working plan to launch an AI Strategy and Action Plan in 2020. Its priorities include reaching consensus on ethics, standards, cybersecurity and regulations (OECD, 2020d). Uruguay is in the process of approving the final draft of its Estrategia Nacional de Inteligencia Artificial para el Gobierno Digital (National Strategy of Artificial Intelligence for the Digital Government) after online public consultation between April and June 2019 (Agesic, 2019).

The risks of mass misinformation: Fake news

Digital technologies now shape daily life, making it easier to communicate and to access and share social and political information. The shift from traditional information channels (e.g. newspapers, radio, television) to digital ones (e.g. social media, websites, private messaging apps) increases exposure to misinformation and so-called fake news. In particular, especially in times of panic or stress (e.g. Covid-19 crisis, election times), our critical skills are impaired and we are less likely to discern between reliable and sensational content. While the impact of misinformation on democratic outcomes is yet to be proven, there appears to be a negative relationship between level of exposure and trust in government (OECD, 2019g). As digital channels gain relevance across LAC countries, policy makers should attempt to stem the proliferation of fake news and empower citizens with critical-thinking tools to evaluate the information they encounter.

The enhanced facility and rapidity with which fake news can spread represent critical challenges posed by new technologies. Digital technologies allow for complex data analyses that can be used to shape information and target it to socio-economic groups or geographical areas to influence opinion. The potential impacts on, for instance, electoral processes raise numerous ethical questions. Similarly, the spread of false information on coronavirus (Covid-19) can negatively affect public health. Digital platforms facilitate the creation of homogeneous social networks that act as echo chambers or filter bubbles, insulating users from contrary perspectives. They allow fake news to reach mass audiences and encourage social polarisation (Lazer et al., 2018; Marwick and Lewis, 2017; Tucker et al., 2018; Wardle and Derakhshan, 2017).

Fake news can be used to discredit authorities or be used by authorities to preserve the status quo or by interest groups to shift public opinion. Aside from facilitating the dissemination of partisan or fake news via algorithmic ranking, digital platforms allow for political campaigning and advertising based on microtargeting and psychographic profiling that enlist user data harvested from social media (Neudert and Marchal, 2019). Big Data analytics add a new layer to the fake news phenomenon, as they enable targeting of political messages based on individual wants and needs, as the Cambridge Analytica scandal showed.

On the other hand, recent scandals concerning the massive reach and impact of fake news have made citizens question the reliability of information on social media. In 2019, 53% of the LAC population believed that false information was spread frequently or very frequently to influence elections (Pring and Vrushi, 2019). Three in four believed as much in Brazil, where confidence in news overall decreased by 11 percentage points in 2019 over the previous year (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2019).

The limited evidence suggests that the impact of fake news on public opinion is large, at least in terms of number of people exposed. In the month preceding the 2016 US election, Americans were exposed to between one and three fake news stories (Allcott and Gentzkow, 2017). Similarly, of the around 126 000 tweets investigated in 2006-17, falsehoods diffused significantly faster, deeper and more broadly than truths, with the effects being more pronounced for false political news than for false news on terrorism, natural disasters, sciences, urban legends or financial information (Vasoughi, Roy and Aral, 2018). Studies tend to focus on the number of individuals who shared or interacted with fake news; quantifying the number affected by it is less evident and could be significantly greater (Lazer et al., 2018).

Policy makers have a responsibility to ensure that citizens have access to true and reliable information (OECD, 2017b). Taking action against fake news is critical to improving trust in public institutions, especially in LAC, where trust in social media as a channel for news is above the world average, although it has fallen in all countries surveyed, except Argentina: in 2019, trust in social media news was highest in Mexico (39% of respondents), followed by Chile (32%), Argentina (32%) and Brazil (31%), compared with a 23% world average. Social media is the preferred way to access online news for 42% of respondents in Chile, followed by search engines (21%) and directly from news websites or apps (19%). Similar trends are observed in Brazil (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2019).3

Media regulation and media literacy are the two main interventions used to tackle the problem. Media regulation consists of structural changes aimed at preventing exposure. Platforms have taken steps in this direction. WhatsApp introduced a limit on message forwarding to five chats at once to prevent spam. Facebook made changes to its algorithm and, together with Twitter, now publishes a transparency report on the number of malicious activities observed on the platform. Twitter reported having verified 14 million to 20 million accounts under suspicion of malicious or spam activity per month between January and June 2019 (Twitter, 2019).

The shift from social media platforms, such as Facebook, to private messaging apps, such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, to access online news may hamper the fight against fake news. Some 53% of Brazilians surveyed reported using WhatsApp to access news,4 and 58% of WhatsApp users in Brazil reported using groups to interact with people they did not know.5 The respective figures were 9% and 12% in the United Kingdom, and 6% and 27% in Australia (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2019).

Media literacy is a complementary intervention empowering individuals with skills and tools to evaluate the news they encounter, including through fact-checking and news-verification initiatives (Lazer et al., 2018). Such initiatives have surged in LAC, in some instances via journalism in the run-up to elections, e.g. Chequeado and Reverso in Argentina, Agencia Lupa and Comprova in Brazil, Colombiacheck, Ecuador Chequea, VerificadoMX in Mexico and Verificado.uy in Uruguay. Governments have encouraged other media literacy initiatives, such as Gobierno Aclara in Costa Rica and #VerdadElecciones2019 in Colombia. More recently, initiatives have emerged to fight misinformation about the coronavirus (Covid-19) crisis. In Colombia, the UN Centre for Information put in place strategic partnerships with local radio stations and news agencies to monitor fake news. It also manages the Voces Unidas radio station, which answers questions or doubts about the virus in both Spanish and indigenous languages (UN, 2020a).

The non-territoriality and global scope of fake news indicates a need for exploring networks of co-operation at the regional and international levels, sharing best practices on countering disinformation and organising co-ordinated responses. The Rapid Alert System, established as part of the EU Action Plan against Disinformation, is an example of international co-operation (European Commission, 2019c). Developed ahead of the 2019 European Parliament elections, the Action Plan was a comprehensive effort to tackle fake news at the state level. It aimed to: improve detection, analysis and exposure of disinformation; strengthen co-operation and joint responses to threats via a dedicated Rapid Alert System; enhance collaboration with online platforms and industry to tackle disinformation; and raise awareness and improve social resilience (European Commission, 2018). The European Union also developed the Code of Practice on Disinformation, a voluntary, self-regulatory set of standards to fight disinformation signed by platforms, leading social networks and the advertising industry.

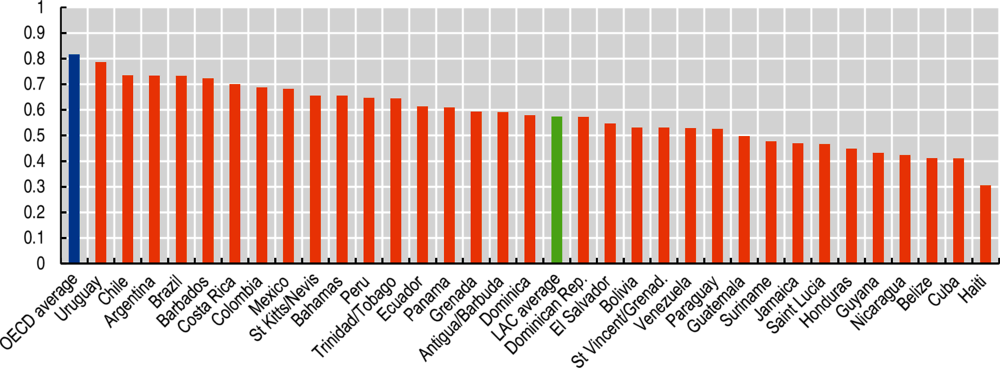

From e-governments to digital governments in LAC: Where are we?

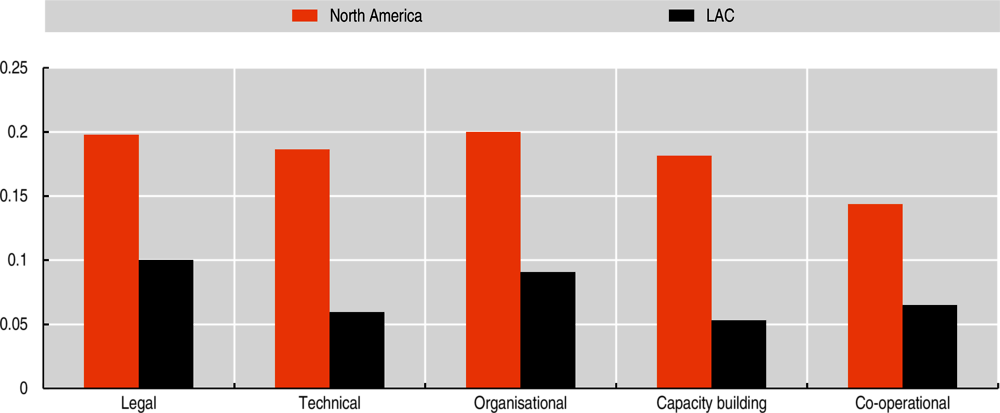

Incorporation of digital technologies to transform public institutions is evolving rapidly. Three main stages can be identified (Figure 4.2). Analogue government was based on analogue procedures. E-government consists in “the use by the governments of information and communication technologies (ICTs), and particularly the Internet, as a tool to achieve better government” (OECD, 2014c). E-government makes more content and information available on line, but there is little interaction with citizens, and management practices remain hierarchical.

Digital government is defined as “the use of digital technologies, as an integrated part of governments’ modernisation strategies, to create public value. It relies on a digital government ecosystem comprised of socio-economic actors of the country which support the production of and access to data, services and content through interactions with the government” (OECD, 2014c). Progress towards the digital transformation of government entails a radical shift in public sector culture with respect to participation, policy making, public service delivery and collaboration. The OECD Digital Government Framework outlines six dimensions of a digital government: digital by design, user-driven, government as a platform, open by default, data-driven and proactive. Whereas e-government had a technology focus, digital government is about embedding a digital culture throughout the practice of government that focuses on meeting users’ needs by re-engineering and redesigning services and processes. Technology is a background enabler, woven into the ongoing activity of improving government, rather than the driver of transformation (digital by design) (OECD, 2019h).

New technologies have changed expectations of engagement with government. Digital technologies enable new forms of stakeholder participation, occasioning a shift from citizen-centric approaches, whereby government anticipates citizen and business needs, to citizen-driven approaches, whereby citizens and businesses identify and respond to needs in partnership with government (OECD, 2014c). In such public administrations (user-driven), government is no longer a service provider, but a platform for the co-creation of public value (government as a platform) enabled by the disclosure of data in open formats (open by default) (OECD, 2019h).

Using the full potential of new digital technologies and data in the design, delivery and monitoring of public services and policies can transform governments. A truly data-driven public sector should: 1) recognise data as a key strategic asset, define its value and measure its impact; 2) reflect active efforts to remove barriers to managing, sharing and re-using data; 3) apply data to transform the design, delivery and monitoring of public policies and services; 4) value efforts to publish data openly and the use of data between and within public sector organisations; and 5) understand the data rights of citizens in terms of ethical behaviours, transparency of usage, protection of privacy and security of data (OECD, 2019b). In turn, the automatic processing of data allows governments to anticipate and respond quickly to emerging public issues or needs, rather than react (proactive) (OECD, 2019h).

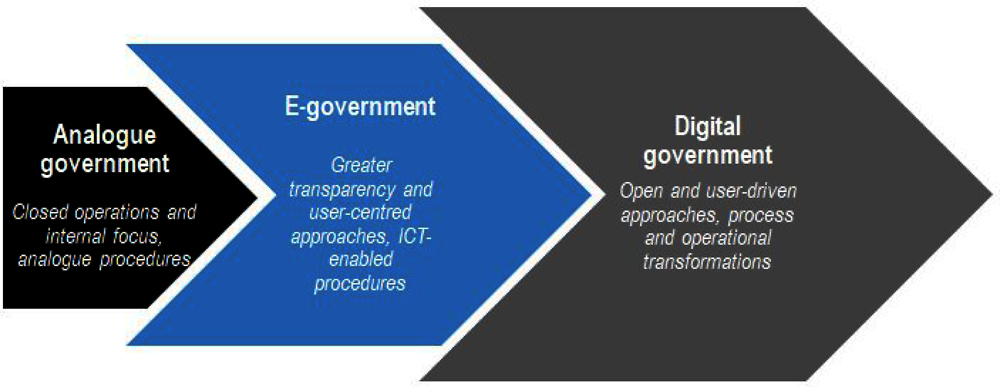

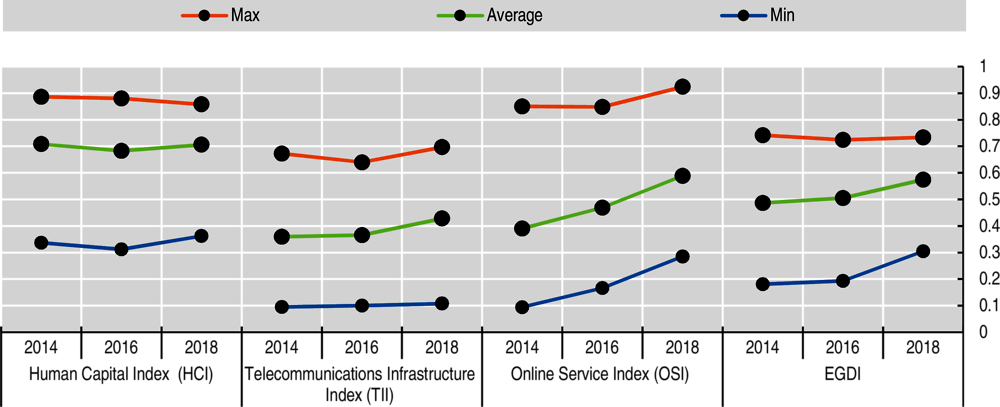

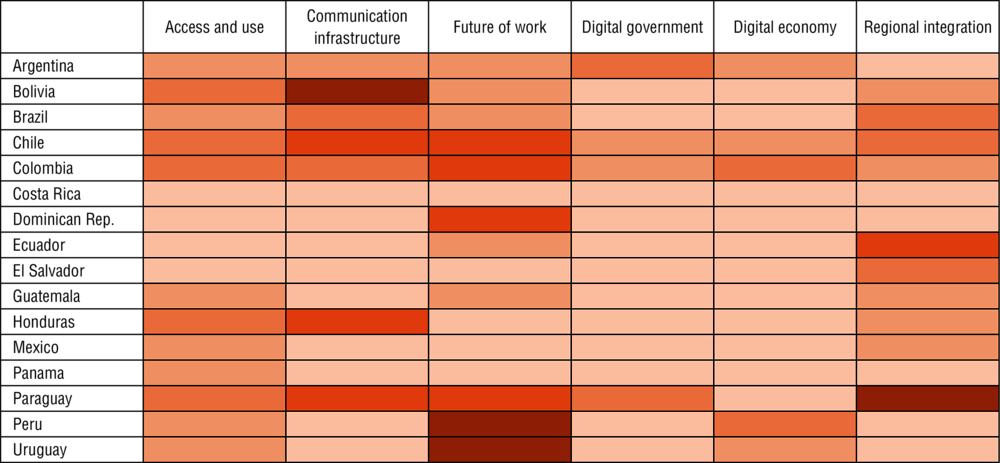

LAC countries are at various stages of the digital transformation of their governments. While it does not capture all the dimensions of a fully digital government, the UN E-Government Development Index (EGDI) is a comprehensive measure of e-government development world wide and an internationally recognised benchmark for comparing countries’ efforts. It is based on measures of online services, communication infrastructure and human capital. In LAC, Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay stood among the top 50 performers of the 193 countries surveyed in EGDI 2018, performing slightly below the OECD average. Belize, Cuba, Haiti and Nicaragua were among the worst LAC performers (Figure 4.3; UN, 2019). In-depth country analysis on the state of the digital transformation of governments in LAC can be found in the OECD Digital Government Studies series covering Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Panama and Peru.

The greatest challenges for LAC countries are in the dimensions of telecommunications infrastructure and human capital, according to the evolution of the EGDI sub-indices between 2014 and 2018. The dimension of online services showed a moderate advance in the period (Figure 4.4). This highlights the difficulty of changing structural variables, such as human capital and infrastructure. The design and implementation of e-government strategies has been a main factor in the advancement of online service provision in LAC countries.

The shift from e-governments to digital governments has not yet taken place in statistical systems. At present, there is no measure of digital government able to capture all of its dimensions. Various scattered indicators show that Chile, Mexico and Uruguay are advancing rapidly in the provision of online government services (Figure 4.9), and Colombia is making progress in open government data (OGD) policies (Figure 4.12). However, neither of these measures yields a comprehensive picture of the state of the digital transformation of governments. The OECD is currently developing a new generation of Digital Government Indicators (Box 4.2).

Most international measurements still focus on government use of technologies to support the digitisation of existing processes, procedures and services (e-government) rather than on the characteristics that make a government fully digital. The OECD developed a set of Digital Government Indicators encompassing the six dimensions of a digital government (digital by design, user-driven, government as a platform, open by default, data-driven and proactive), which can be used as a maturity index, enabling governments to assess progress in each dimension.

This project is a first attempt to measure the digital transformation of the public sector. It is the result of a collaboration between the OECD Digital Government Unit of the Public Governance Directorate and the OECD Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders). It builds on the theoretical framework of the 2014 Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies and resulting peer reviews. The index will not only provide a tool for benchmarking across countries, but also a basis for monitoring their efforts to implement the Recommendation (OECD, 2019i).

Moving towards more credible, efficient, inclusive and innovative public institutions

The digital transformation represents a unique opportunity to transform public institutions deeply and adapt them to rising social aspirations. In a rapidly changing world, development processes demand agile public institutions that are ready to meet emerging challenges and embrace new opportunities. The Latin American context has been characterised by a growing divide between citizens and institutions, leading to an institutional trap that acts as a vicious circle of low trust, declining willingness to pay taxes and, consequently, low public resources to finance good-quality public services and meet citizen demands (OECD et al., 2019). This section explores opportunities offered by the digital transformation to move towards public institutions in LAC that are more credible, effective, inclusive and innovative.

Although not the focus of this section, infrastructure development and investment in civil servants’ digital skills are two essential prerequisites to ensure a successful digital transformation of governments. Infrastructure development must close the digital divide, so all citizens can equally access public services on line and engage with government and each other digitally. Digital literacy and culture in public administration are essential to make the most of digital technologies and respond to new challenges (see Chapter 3). Beyond user skills with digital technologies (e.g. email, word processing, spreadsheets, workflow apps) and soft and hard digital skills in public-sector professions (e.g. data analysts), complementary digital skills are increasingly required for public functions profoundly transformed by digitalisation (e.g. tax collection, government communications, citizen services management, planning) (OECD, 2019j). Digital management and leadership skills are also necessary for acknowledging the opportunities, benefits and risks of using digital technologies in the public sector (OECD, 2017c).

Towards more credible public institutions

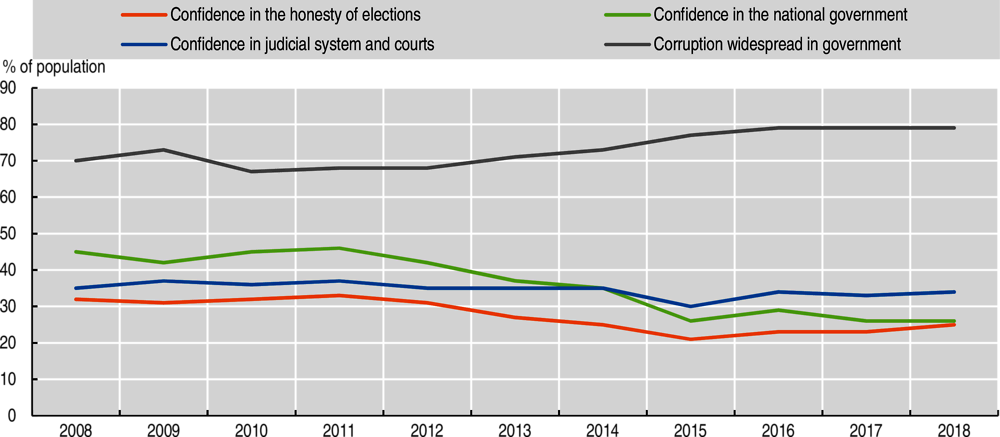

Trust in public and democratic institutions has declined in LAC in recent years. In 2018, 26% of the population had confidence in the national government vs. 45% in 2008, 21% in Congress (vs. 32%), 24% in the judiciary (vs. 28%) and 13% in political parties (vs. 21%) (Figure 4.5). Perception of democracy has also undergone significant erosion (Figure 4.6).

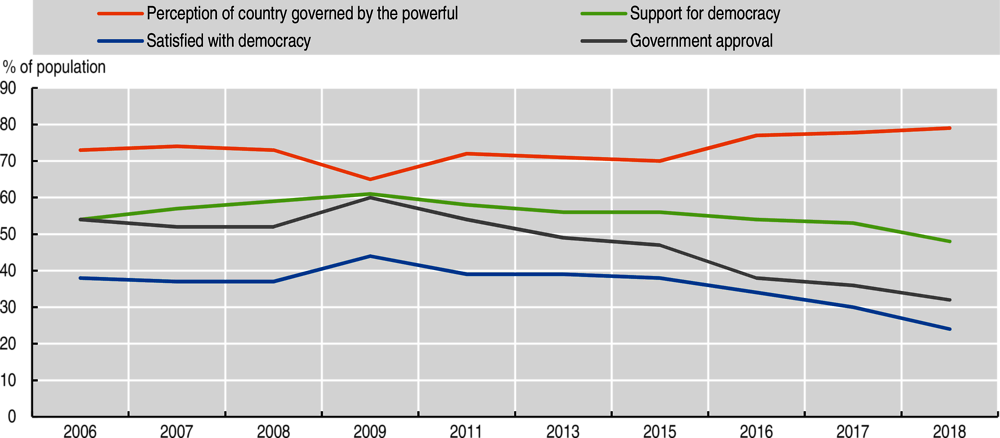

Widespread perception of corruption is a main driver of mistrust in public institutions. In 2018, 79% of the LAC population believed corruption was widespread in government (Figure 4.5). Some 53% thought corruption increased between the end of 2018 and the end of 2019 (Pring and Vrushi, 2019). This deepens public perception that economic and political elites exert a strong influence on policy decisions for private gain. Some 79% believed the country was governed by, and for the benefit of, a few (Figure 4.6).

Trust is a cornerstone of public governance and fundamental to the success of public policies. Many policies depend on the co-operation and compliance of citizens, while many others assume the public will behave in a way that translates policies into effective action (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018).

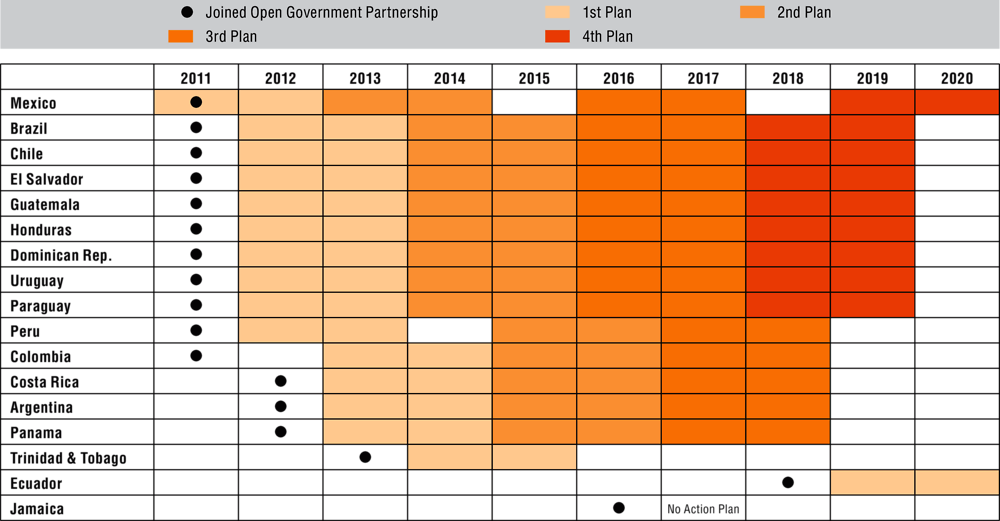

Open government, as a paradigm of public management, can contribute to addressing these challenges, emphasising the importance of transparency, access to information, collaboration and citizen participation (Naser, Ramírez-Alujas and Rosales, 2017). LAC countries have demonstrated commitment to open government (Figure 4.7): by January 2020, there were 53 action plans in the region – 38 already implemented and 15 in progress. Moreover, 1 116 action commitments were added, reflecting the relevance of open innovation as a modality of collaboration with citizens for the co-creation of solutions.

Access to information is a fundamental aspect of open government, and OGD is a natural evolution of the proactive publication of public information. Open data have thus become a central component of open government plans. Increased data availability opens up new possibilities to increase the trustworthiness of public institutions. The potential of OGD strategies to improve democratic governance is large, as open data availability supports a culture of transparency, accountability and access to public information. OGD puts large amounts of information in the hands of citizens, civil society and international organisations, which can then play an oversight role and act as watchdogs and whistle-blowers in cases of corruption or malpractice. The availability of budget and public finance data was critical in uncovering large-scale corruption scandals in the region, such as the Panama Papers or the Odebrecht corruption network (Santiso and Roseth, 2017).

Digital technologies can improve areas particularly susceptible to corruption, including public contracts, infrastructure investments and transfers from national to subnational authorities. While there is room for improvement, LAC has seen progress in these areas. MapaInversiones is a regional Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) initiative to support countries in creating digital platforms for data visualisation. Its main objective is to improve the transparency and efficiency of public investment. The platforms can be used by citizens to exert social control over the use of public funds, by the private sector to prioritise investment, and by policy makers to strengthen planning, design and implementation of public policies (Kahn, Baron and Vieyra, 2018). Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Paraguay and Peru have implemented such platforms. In Colombia, the MapaRegalías platform, which shows the origin and destination of financial resources obtained from the exploitation of natural resources, has helped identify numerous irregularities (Santiso, 2018). Since its launch, the implementation efficiency of projects financed with royalties increased by 8%, on average (Lauletta et al., 2019).

The creation of central purchasing bodies as centres of procurement expertise, and the development of e-procurement solutions, are transforming traditional practices in LAC. ChileCompra and Colombia Compra Eficiente are two e-procurement platforms providing transparent information on public contracts, for instance. In addition to improving transparency in public management, the data generated by e-procurement platforms can be re-used for anti-corruption purposes through Big Data and machine learning techniques. The OCEANO system, developed by Colombia’s General Comptroller, cross-checks information derived from the e-procurement system, administered by Colombia Compra Eficiente, with the business and social register to detect corruption networks (Cetina, 2020). Brazil’s Observatory for Public Expenditure tracks and cross-checks procurement expenditure data with other government databases to identify atypical scenarios that, while not a priori evidence of irregularities, warrant further examination. The platform revealed fraud in Brazil’s largest social welfare programme, Bolsa Família.

Blockchain is another emerging technology that can support the integrity of public institutions and prevent corruption. Blockchain allows for recording assets, transferring value and tracking transactions in a decentralised manner, ensuring data transparency, integrity and traceability. It eliminates the need for intermediaries, cuts red tape and reduces the risk of arbitrary discretion.

Social media and online audio-visual mediums can help build trust in the management of crises. As seen during the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, conflicting government messages make it hard for the public to know how serious the risks are and what to do. Disinformation and fake news can exacerbate the trend and create panic and confusion (De La Garza, 2020). Governments should ensure that clear, trustworthy information channels reach the greatest number. Social media can provide an important platform to inform citizens about risks, the evolution of the crisis and the measures adopted to counter it. Examples include digital awareness-raising campaigns and daily briefs shared on official government social media accounts. This channel can be especially effective in LAC, given the high use of social media. News verification initiatives can also help counter the spread of fake news (see the section “The risks of mass misinformation”). The UN launched Verified, a platform to increase the volume and reach of trusted, accurate information on the crisis (UN, 2020b).

Social media and search engines can also help governments better manage crises by highlighting, surfacing and prioritising content from authoritative sources (Donovan, 2020; OECD, 2020e). Social media algorithms usually promote the most engaging content, risking heightening the spread of sensational fake news. However, during the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, digital platforms pinned informative government websites to the top of their coronavirus (Covid-19) search results. For instance, Google tweaked its algorithm so that the top search results provided a panoramic overview of the outbreak, information on symptoms, preventive tips and links to national government and World Health Organization (WHO) websites. Other initiatives included co-operation with fact-checkers and health authorities to flag and remove disinformation, and granting free advertising spaces to health authorities to disseminate critical information on Covid-19 on-line (OECD, 2020e).

Digital technologies also pose new challenges for institutional trust. The increasing interconnectedness favoured by technological advances may create new paradigms of social progress. Easier comparison with progress in LAC countries at higher levels of development may inflate aspirations among younger generations, leading to frustration with public institutions if there is a perception that these are not delivering (Nieto-Parra, Pezzini and Vázquez, 2019). Widespread access to information can also be a source of vulnerability for trust in public institutions, insofar as the Internet is used to spread propaganda and fake news and misinform citizens. Fighting fake news is complex, but initiatives are emerging to counter its pervasive impact on public trust (see the section “Governing the digital transformation”). Moreover, the Internet can affect political attitudes and, in certain circumstances, decrease public confidence in government (Guriev, Melnikov and Zhuravskaya, 2019).

Towards more efficient public institutions

As governments face significant public spending constraints and struggle to meet growing expectations, digital technologies can help make public services more efficient by cutting transaction times and administrative costs.

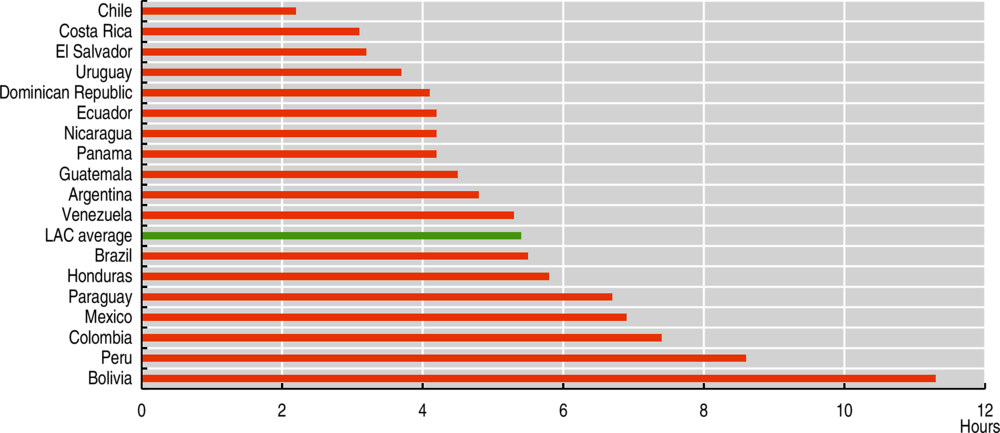

LAC’s complex bureaucracy is best exemplified by the average time it takes to carry out a government transaction, such as getting a birth certificate, paying a fine or obtaining a licence. It takes 5.4 hours, on average, to complete a public transaction in LAC, although variation among countries is high, ranging from more than 11 hours in Bolivia to less than 3 in Chile (Figure 4.8). A high proportion of transactions require three or more interactions with officials, resulting in high transaction costs for citizens, who have to dedicate time and money to dealing with institutions, and for governments, which have to invest financial resources in dealing with citizens face-to-face, reviewing documents and responding to queries. Digital tools can help reduce this burden, for instance the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham reduced processing time by 30 days and saved GBP 617 000 per year by digitalising benefit claims (Local Government Association, 2014).

Transaction times and administrative costs could be reduced through bureaucratic simplification and automation using technologies. Establishing a digital channel for processing transactions would eliminate in-person time and cost for citizens. Establishing interoperable automated systems among government institutions would further reduce and simplify steps to complete a transaction. Such transformation depends on interinstitutional co-ordination among government bodies. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies called for “providing the institution formally responsible for digital government co-ordination with the mechanism to align overall strategic choices on investments in digital technologies” (OECD, 2014c).

Administrative reforms in LAC countries mainly focus on whether regulations can be simplified or eliminated.6 For instance, the Dominican Republic launched RD+ Simple, a website to report on burdensome regulations or administrative processes. Argentina developed a similar website. Yet, only half of the ten countries surveyed (Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru) had undertaken administrative simplification at the regional and municipal levels, with little progress shown since 2015-16 (OECD, 2020f).

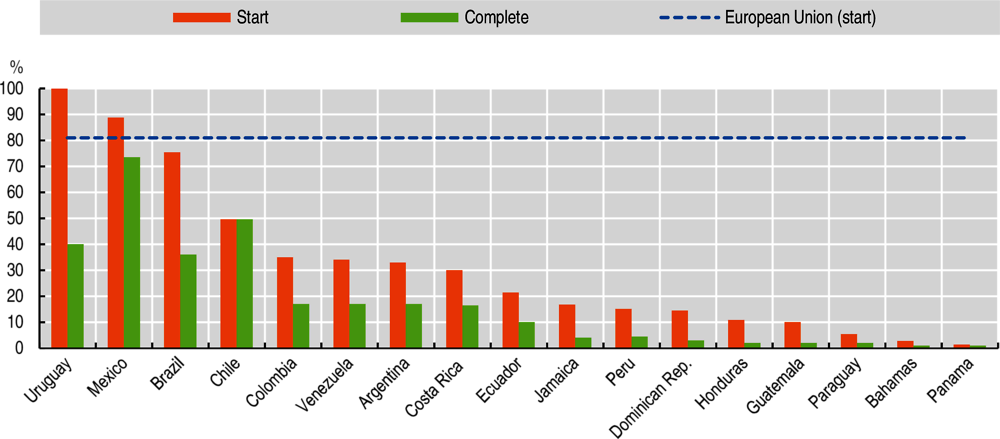

With respect to automation, use of digital transactions in LAC is heterogeneous, but remains rare in the majority of countries. This is usually because: 1) transactions are not available on line; 2) the public cannot access online transactions (e.g. due to lack of broadband access, identification or debit card); and 3) the experience with available, accessible online transactions is unsatisfactory (Roseth, Reyes and Santiso, 2018). Mexico and Chile are the only LAC countries in which more than half of government transactions can be started and completed on line (Figure 4.9). An inclusive digital transformation should not forget the physical service delivery channel, as it remains important in many LAC countries, especially for older and less digitally savvy citizens, and those without Internet access.

During service transformation, service design is a critical discipline that helps governments: 1) understand a user’s journey from first attempt at solving a problem to final resolution (from end to end rather than within organisational siloes of provision); 2) address citizen-facing experiences and back office processes (external to internal and vice versa) as a continuum rather than two separate models; and 3) create consistency of access and experience between and across channels (omni-channel) rather than adopt different solutions for different channels (multi-channel) (OECD, forthcoming).

The six-year project, initiated in 2012, to transform the justice system in Panama is an example of successful service design and implementation. The collaboration between the National Authority for Government Innovation and several stakeholders focused on both digital elements and physical infrastructure problems and analogue interactions, addressing the end-to-end experience. Paper is no longer involved, and the justice system has reduced time investment by 96% (OECD, 2019j). The digital transformation of Colombia’s Attorney/Inspector General’s Office (PGN) is another promising initiative. Through a digital filing project, it is expected that all PGN cases will be fully operational at all PGN offices using: 1) optimised workflows that facilitate direct interaction between officials and citizens via digital channels; 2) digital document processing, content management and user services; and 3) access to information from legacy systems. Yet, despite virtuous exceptions, the justice system remains one of the least digitalised sectors of public administration in LAC.

In addition to simplification, automation and service design, adoption of interoperable systems among public administrations is key to more efficient governments. Integrating data systems from different government bodies requires significant digitalisation of databases that share reporting standards and identifiers. Automated cross-checks of tax, wealth, social and payroll data could result in more effective targeting of social transfers and detection of tax evasion (Izquierdo, Pessino and Vuletin, 2018). By integrating information on beneficiaries of various programmes, Iraq’s Social Safety Net Information System allowed the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs to identify households receiving multiple benefits to which they were not entitled. Exclusions resulted in savings of USD 18 million in the system’s budget for Baghdad alone. Estonia and Korea are the most advanced in system integration, but Argentina’s national fiscal and social system of identification (SINTyS), Chile’s integrated system for social information (SIIS) and Brazil’s Cadastro Único have achieved remarkable levels (Barca and Chirchir, 2014).

Uruguay’s national electronic health record (EHR), Historia Clínica Electrónica Nacional, features similar integration. While providers manage their own systems, shared data standards make information interoperable. Patients can receive personalised health care anywhere in the country because their records, including medical visits, examination results and mobile consultations, are shared across providers on a platform (Bastias-Butler and Ulrich, 2019).

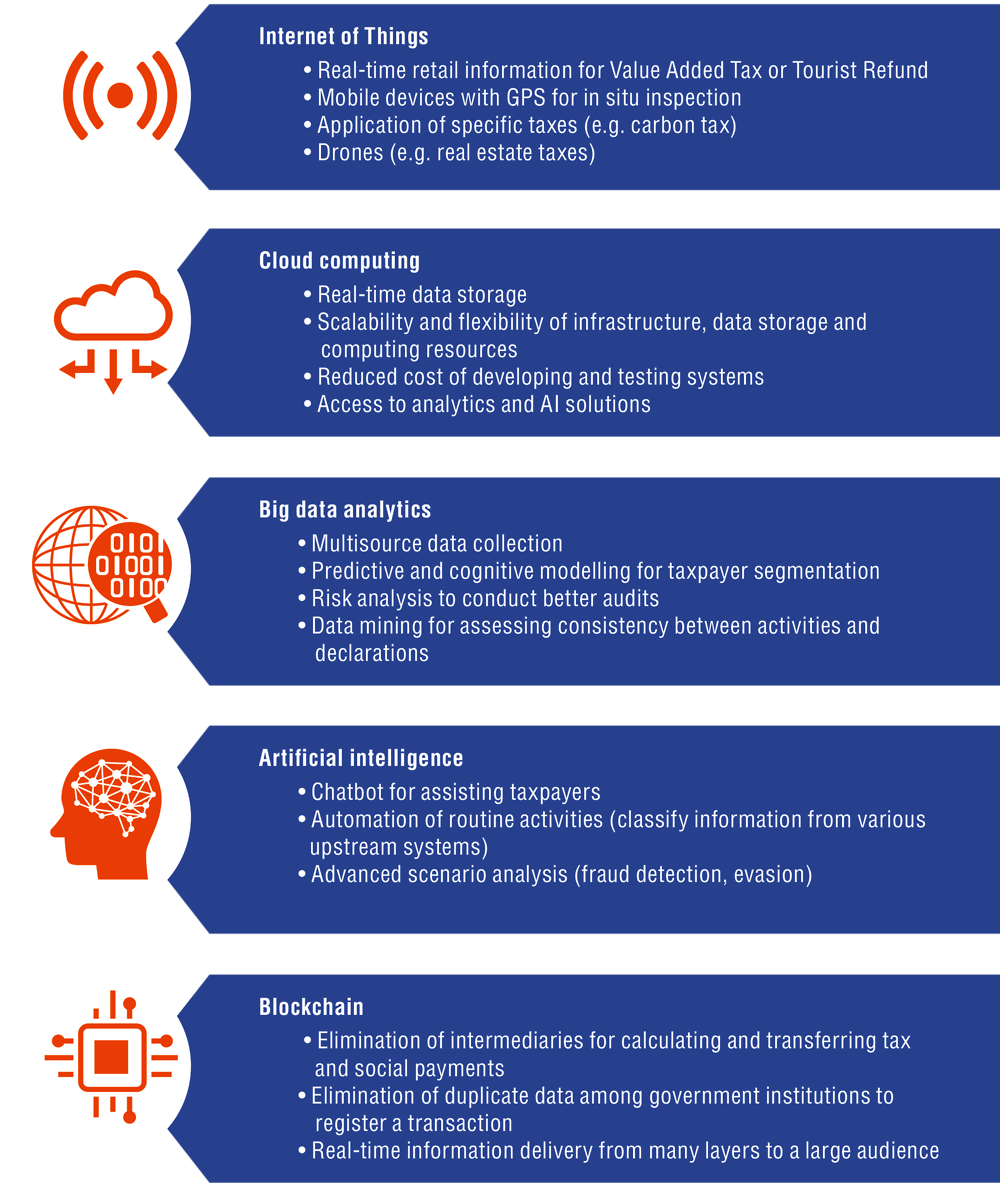

The digital transformation of tax administration can positively affect process efficiency and service delivery (OECD, 2019k). Digital technologies open up new ways to collect, store, manage and analyse tax information. Income tax filing is one of the most diffused online government services globally (UN, 2019). Latin America leads the way in e-invoicing, which electronically records and automatically transfers commercial transactions to tax authorities. E-invoicing helps fight tax evasion by providing real-time information and making cross-referencing tax filings easier (Barreix and Zambrano, 2018; Bellon et al., 2019). Chile was the first to adopt e-invoicing in 2003, followed by Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay and other LAC countries. Ecuador has gradually introduced e-invoicing since 2013. In 2016, taxpayers who already emitted e-invoices reported 24% more taxable sales than those not yet included in the programme, up from 17% in 2015 (Ramírez Álvarez, Oliva and Andino, 2018). Other digital technologies, such as the IoT, cloud computing, Big Data analytics, AI and Blockchain, offer new opportunities to increase the efficiency of tax administration (Figure 4.10).

Towards more inclusive public institutions

The digital transformation can make public institutions more inclusive by facilitating interaction with stakeholders (e-consultation) and citizen engagement in decision making (e-decision making). Digital platforms can be a low-cost means for governments to interact with stakeholders in policy design, monitoring and implementation. The digital transformation can help governments provide more inclusive public services, making public institutions more accessible and citizen centred. Using digital technologies, public institutions can develop policies that are better targeted and put citizen experience at the centre of their design.

According to the 2018 UN E-Participation Index, which includes measures of e-information sharing, e-consultation and e-decision making, the performance of Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Uruguay was above the OECD average, while other countries lagged far behind (Figure 4.11).

Digital technologies are opening up innovative channels for stakeholder engagement at various stages of the policy-making process. In 2018, the city of Montevideo set up the Montevideo Decide platform to foster and facilitate citizen participation in public matters through debates, proposals and participatory budgets. One of the more innovative features is a space for citizens to make proposals to the city and choose the winning option(s), to which the city then commits. Chile’s Vota Inteligente was a similar open and participatory platform aimed at transmitting proposals to electoral candidates in the 2017 elections. Brazil’s Promise Tracker allows citizens to track authorities’ compliance with their commitments and promotes spaces of dialogue between citizens and authorities to find shared solutions to pressing challenges. Citizens can also increase their participation in legislative processes through CrowdLaw, which uses technology to tap the knowledge, creativity and expertise of citizens to improve the law-making process. Communication is a critical aspect of successful public policies. Digital technologies offer many opportunities for true public engagement and strengthening the impact of government communications (Box 4.3).

The digital transformation of governments can also support inclusive public services by reaching remote and disadvantaged segments of society that have difficultly accessing services. Digital technologies have expanded the reach of public education, for instance. Among other developments, e-learning alternatives have undergone an extraordinary transformation in recent years. Massive open online courses have the potential to democratise education by expanding access and providing many with opportunities for flexible career paths more closely aligned with labour market needs (OECD, 2015b). E-health delivery systems, such as remote consultations, portals and wearable devices, open up new options for on-demand non-emergency health care that covers more patients at lower cost. These digital modalities may allow a refocussing of health-care services on prevention and early diagnoses (Pombo, Gupta and Stankovic, 2018). One-and-a-half years after implementation of the online service, Peru had carried out 6 800 telemammographies and diagnosed 39 cases of breast cancer in areas with no radiologists (Peru Ministry of Health, 2018).

Government communications are an indispensable tool for public institutions to build trust, boost taxpayer morale and encourage public participation. Digitalisation brings unprecedented opportunities for government communications.

Social media provides a relatively inexpensive way to reach millions of citizens. Governments can build support for policy and demonstrate progress with engaging online formats (e.g. video, digital storytelling, data visualisations), promote behavioural change and encourage citizens to join national and local efforts to achieve sustainable development.

The most innovative institutions treat online media not as new broadcasting channels but as multiway processes, creating platforms where citizens can shape debate and communicate their own messages.

Digitalisation also provides governments with a precious information source. With data analytics and online consultations, they can better anticipate public debate, understand audience segments and develop more engaging and effective messaging (OECD, 2020g).

These digital solutions played a crucial role during the coronavirus (Covid-19) crisis. Schools adapted content and went digital to ensure continuity (see Chapter 3). Doctors provided e-consultations to mitigate emergency room overcrowding and viral spread. Recent events have laid the groundwork for an emerging e-health services market that could be developed beyond national borders (Blyde, 2020), similar to e-learning. Low culture and language barriers in LAC could generate important economies of scale for e-health and e-learning providers. However, if complementary investments are not made to ensure equal access to communication infrastructure and skills, these digital services may benefit a small part of the population, exacerbating inequalities in the region (Basto-Aguirre, Cerutti and Nieto-Parra, 2020).

Towards more innovative public institutions

The digital transformation can help governments be more innovative in all stages of policy making, thereby improving the quality of public policies. Digital technologies, combined with data, can be drivers of innovation in public administration by supporting better informed and targeted public policies and services.

Technology, and the digitalisation of societies and governments, generate massive amounts of data. Timely and sufficiently granular data offer opportunities for evidence-based decision making, with digital technologies supporting the policy cycle. Harnessing this potential requires a shift in public administration from an information-centred approach to an innovative, data-driven approach that incorporates digital technologies and data into policy design, delivery and evaluation.

Digital technologies and data promote this approach in various ways. They allow tracking of rapidly changing or previously under-recorded phenomena, such as pollution, financial activity or disease outbreak. Improved data availability, sharing and visualisation help policy makers tailor and differentiate policy design by geographical area, policy setting or socio-economic group (Huichalaf, 2017). Big Data and advanced econometric techniques supported by more granular data allow for greater policy experimentation and evaluation. Last, digital tools facilitate real-time data collection and exchange among both public and private actors, allowing governments to predict and respond proactively to emerging trends or risks (OECD, 2019l). The coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic illustrates the use of digital technologies and data for innovative policy making. The OECD Country Policy Tracker is a visual platform created to monitor and compare coronavirus-related measures (OECD, 2020h). Korea was among the first to use a smartphone app to deliver test results, track adherence to quarantine and map the geographical distribution and evolution of contagion (Kim, 2020). More countries have adopted a contact-tracing tool, one being Go.Data, developed by WHO and Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network partners to collect case and contact data, and visualise disease transmission (WHO, 2020).

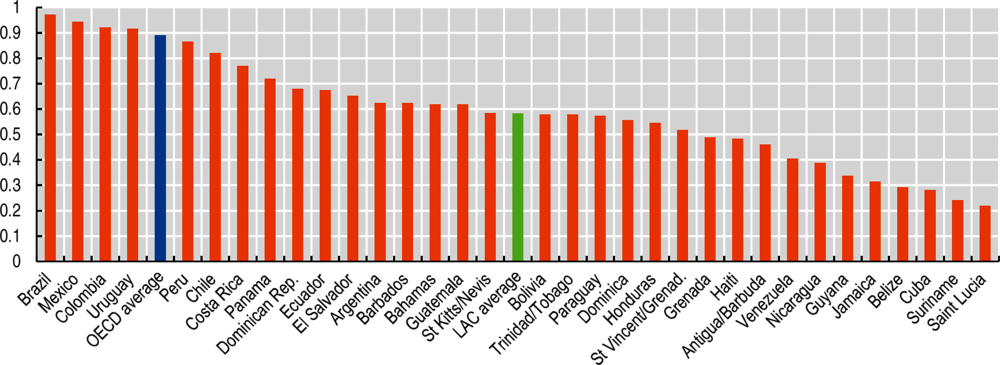

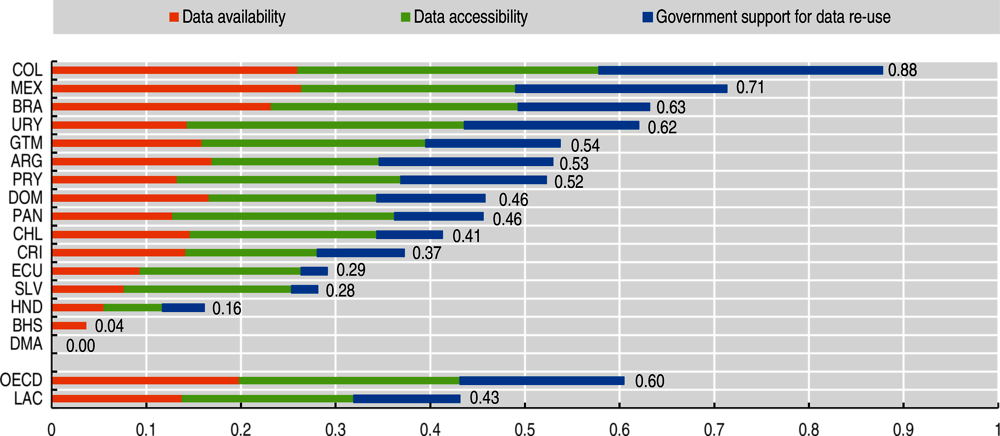

Innovative policy making can be fostered by making data openly available, but also usable and re-usable. OGD policies must be complemented with efforts to make the data re-usable so that they can feed into public administration policy cycles and help firms and individuals make more informed decisions (van Ooijen, Ubaldi and Welby, 2019). The OECD/IDB Open, Useful and Re-usable data (OURdata) Index 2019 measured government commitment to OGD policies, ranging from 0 (lowest) to 1 (highest). LAC countries scored 0.43 in 2019, compared with an OECD average of 0.60. OGD levels are very heterogeneous in LAC: Colombia (0.88), Mexico (0.71) and Brazil (0.63) are leaders, while Caribbean countries, such as the Bahamas (0.04) and Dominica (0.00), are not yet implementing OGD policies (Figure 4.12).

Data availability (Pillar 1 of the OURdata Index), which measures the extent to which central/federal governments promote OGD, shows that, except for Brazil, Colombia and Mexico, LAC is underperforming, compared with the OECD: 10 of the 16 LAC countries surveyed have formal requirements to ensure publication of transparency data. LAC shows better performance in data accessibility (Pillar 2), which measures how OGD are released: 13 of 16 countries, including Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic and Guatemala, provide all or most of the data in machine-readable format on their central portals, and 12, including Argentina, Brazil and Chile, provide all or most of the associated metadata. Except for Brazil, Colombia and Mexico, LAC countries most lag in government support for data re-use (Pillar 3). In particular, countries could better monitor the impact of OGD, since the LAC average score in this sub-category is 0.07, compared with 0.14 for the OECD (Figure 4.12) (OECD, 2020f).

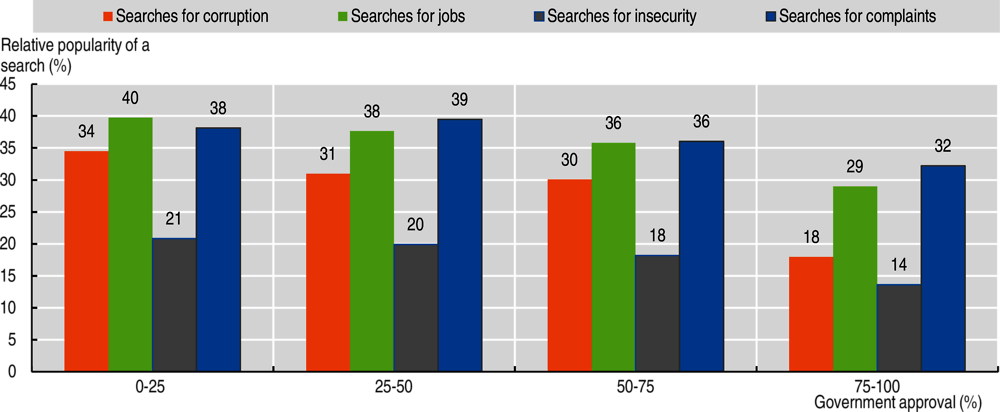

Innovative governments should explore the potential of public-private collaboration in the exchange of data to inform public policies. Search engine data can provide invaluable information that complements traditional socio-economic and institutional data. In contrast to traditional citizen surveys or macroeconomic indicators, such as GDP growth, inflation or unemployment rates, data generated by Internet searches can inform public policies with readily available, anonymous, high-frequency data. For instance, the frequency of Google Trends searches for terms related to government corruption, public services complaints and insecurity have a statistically significant negative association with government approval in the region, after controlling for traditional macro variables (Montoya et al., 2020) (Figure 4.13). Many examples illustrate the potential of public-private collaboration to address policy issues (Socías, 2017). Throughout the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic and 2014 Ebola crisis, mobile phone data were used to map regional population movements, identify areas at increased risk of outbreak and determine where to focus preventive and healthcare measures (OECD, 2019l). The same type of data can be used to track migration phenomena (Frias-Martinez et al., 2019; Isaacman, Frias-Martinez and Frias-Martinez, 2018) or map poverty, as done in Guatemala (Benjamins et al., 2017; Hernandez et al., 2017). The IDB used Waze traffic data to measure the impact of a Buenos Aires bridge on traffic congestion (Yañez-Pagans and Sánchez, 2019).

To support public sector innovation, it is essential to invest in civil servant skills, including technical skills, as well as a range of softer behavioural and cognitive skills, such as creative thinking and communication. When supported and motivated, front-line staff and middle managers can play a role in bringing forward innovative ideas and working them through at every stage. People management is therefore an important lever to sustain public sector innovation and a key area where countries should focus efforts to raise their innovative potential. In 2014, Chile set up the Laboratorio de Gobierno, a multidisciplinary institution to catalyse citizen-centred public-sector innovation that focuses on developing innovation capabilities and supporting innovative projects in public institutions. Its promising Experimenta programme encourages a learning-by-doing approach and helps civil servants address concrete institutional challenges with a citizen-centric, collaborative approach (OECD, 2017d).

Governments should take a bolder stance in favour of innovation, including by supporting innovative initiatives outside the public sector. Part of this strategy should be support for GovTechs (SMEs and start-ups dedicated to developing digital technology solutions for public administrations). While large companies dominate the market for public administration technology solutions, which generates around USD 400 billion per year world wide, creative entrepreneurs have emerged in LAC (Santiso, 2019).

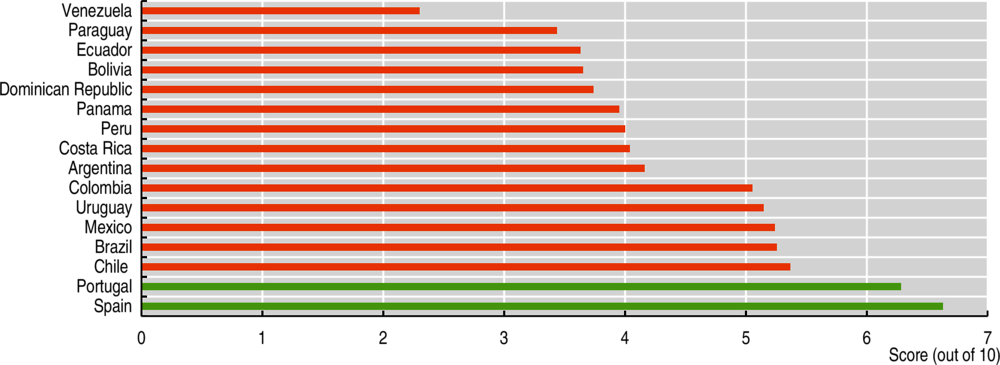

The maturity of GovTech ecosystems across LAC countries is heterogeneous. The Corporación Andina de Fomento (Andean Development Corporation [CAF]) GovTech Index 2020 is the first attempt to measure the development of GovTech ecosystems in the region. Its three pillars assess the start-up industry, government policies to promote the GovTech ecosystem, and the quality and efficiency of procurement systems. The start-up pillar has the lowest score across the region. This is mainly explained by the low availability of the venture capital needed for funding start-ups and scaling up. Portugal and Spain display greater average maturity than their Latin American counterparts (Figure 4.14).

Among successful LAC GovTech initiatives, Visor Urbano is a platform for managing online transactions related to business licences and construction permits of the Government of Guadalajara, Mexico. It has helped fight corruption, supported evidence-based policy making and saved citizens time and money (Zapata and Gerbasi, 2019a).

MuniDigital®, a platform focused on improving municipal services management by collecting accessible, up-to-date data, is currently employed by 40 municipalities and institutions in 10 Argentinian provinces. Government and citizen savings were attributed to, among other effects, improved administrative efficiency and reduced costs related to infrastructure maintenance and public transport, which helped lower environmental costs (Zapata and Gerbasi, 2019b).

Government-GovTech collaboration presents challenges that should be addressed. Fixed, long-term contracts with technology companies prevent public administrations from engaging with newer entrants. The public procurement process is also long and complex: the search for the cheapest solutions and the duration of decision making can result in contracting firms that are competitive, but not innovative (Ortiz, 2018). Regulatory frameworks should focus on lowering entry barriers for innovative start-ups. Colombia’s Compra Publica para la Innovación applies an innovation criterion in procurement to find alternative solutions that satisfy public needs. Brazil and Chile are also making public procurement rules more flexible (Santiso, 2019). Innovation requires upfront and long-term financing (Mazzucato and MacFarlane, 2018). The longer maturation times of companies catering to the public sector deter venture capital funds. The public sector could play a key role in establishing funds for supporting these emerging start-ups. Denmark, Israel, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal and the United Kingdom have taken steps in this direction. Mexico is testing this approach through Reto México.

Digital technologies and new forms of data open up new opportunities for all levels of government, including cities, which is particularly relevant in highly urbanised LAC. Incorporating digital technologies can transform public service provision and quality of life (smart cities). Citizens’ regular interactions with local public administration (e.g. carrying out transactions at local government offices, voting in the constituency or using public transport) influence their perception of public institutions, making investment in digital technologies at the local level critical to improving their well-being and satisfaction with government.

Public institutions and cities can benefit from the digital transformation in terms of credibility, efficiency, inclusiveness and innovation. Data-driven innovation can increase efficiency and promote integration of urban systems. For instance, smart grids can be connected to electric vehicles and home devices to manage energy supply and demand more efficiently. Civic technology can foster citizen engagement by facilitating access to information and providing spaces for expression of opinion, public consultation and online voting. Moreover, digital innovation at the local level often has lower costs and requires less capital expenditure, allowing smaller firms to compete with dominant incumbents in a disruptive ecosystem (OECD, 2019m). Pinhão Valley, the innovation ecosystem of Curitiba, Brazil, includes multiple actors, such as universities, accelerators, incubators, investment funds, start-ups, cultural and creative movements, and civil society.