copy the linklink copied!2. What does Paris alignment mean for development co-operation?

What does development co-operation look like when it is aligned with the Paris Agreement? This chapter outlines its four main characteristics: (i) it does not undermine the Paris Agreement but rather contributes to the required transformation (ii) it catalyses countries' transitions to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways (iii) it supports the short- and long-term processes under the Paris Agreement (iv) it proactively responds to evidence as well as to opportunities to address needs in developing countries. This chapter then discusses how some providers are already actively pursuing Paris alignment, and examines how development finance patterns and allocations point to significant remaining gaps and inconsistencies in integrating climate objectives.

-

This report argues that development co-operation that is Paris-aligned actively supports the core objectives of the Paris Agreement on climate change mitigation, adaptation and finance flow consistency and the country-driven processes established to achieve them. These processes include, in particular, nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and long-term low greenhouse gas emissions strategies.

-

This report identifies a set of key characteristics that describe what Paris alignment looks like for development co-operation. The characteristics propose that aligning development co-operation with the objectives of the Paris Agreement means ensuring that activities make an overall positive contribution to the global shift to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways. Paris-aligned development co-operation does not undermine effective climate action. Rather, it proactively supports and catalyses countries’ climate action, facilitating more robust and ambitious NDCs and long-term strategies and responding to evidence and emerging opportunities in developing countries.

-

In recent years, various providers of development co-operation have made useful progress on Paris alignment and increasingly situate climate action at the centre of sustainable development. Nevertheless, further efforts are needed.

-

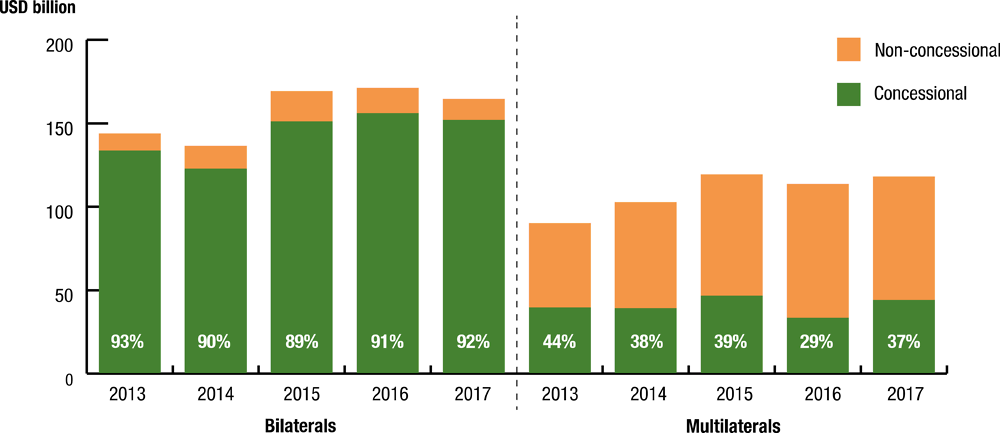

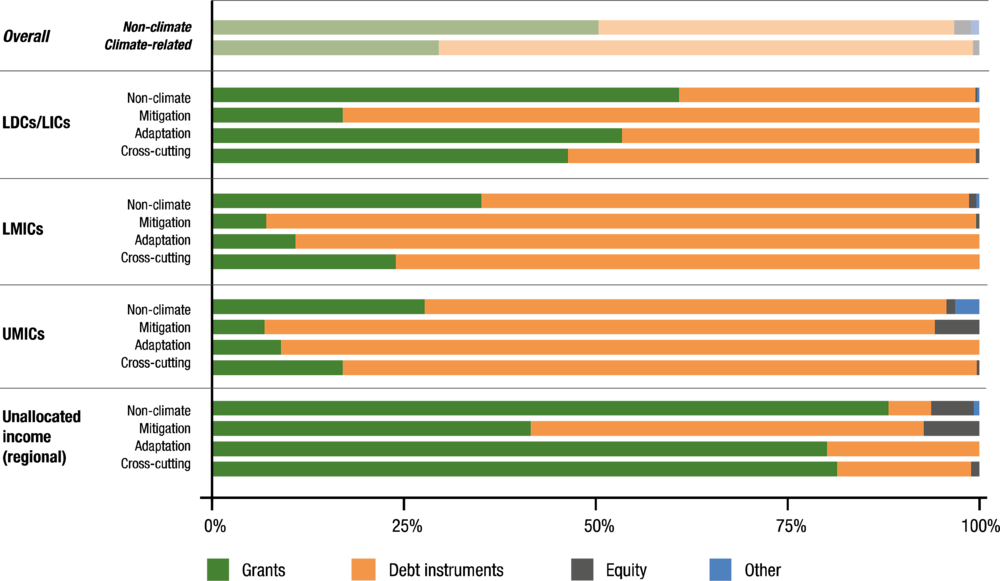

Providers are not sufficiently integrating climate considerations across portfolios. Climate-related development finance accounted for 18% of bilateral and 32% of multilateral development finance in 2013-17. But climate-related development finance is not trending strongly upward, suggesting insufficient action in development co-operation to date.

-

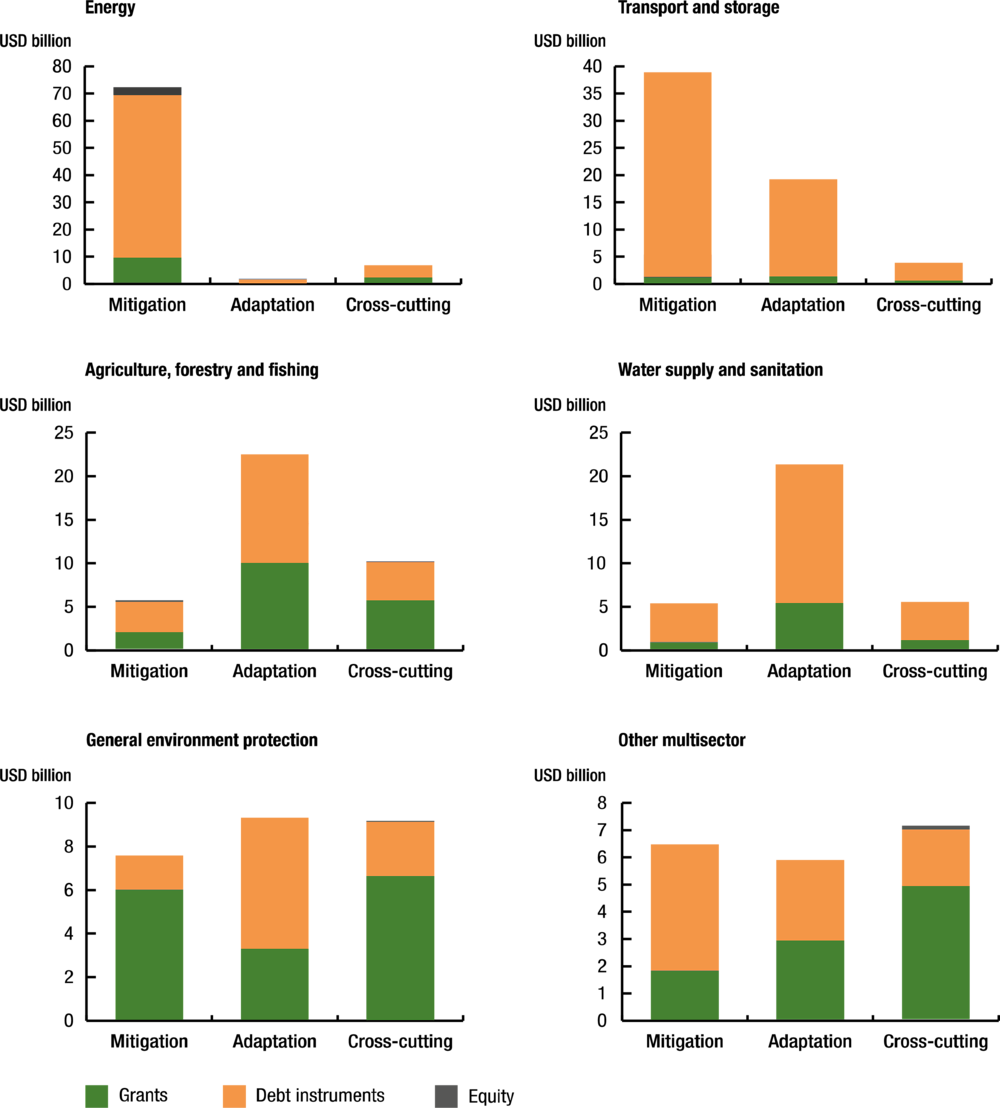

Climate-related development finance has so far been concentrated in the sectors typically viewed as central to transitioning towards low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways. But it remains a relatively small share of overall development finance in certain sectors that are increasingly recognised as critical to effective climate action, such as banking and financial services and health. This indicates that providers should more thoroughly integrate climate objectives across all sectors.

-

Development finance needs to achieve a better balance between countries’ needs for mitigation and adaptation objectives across sectors.

copy the linklink copied!2.1. Paris alignment means supporting ambitious climate action and reinforcing the principles of sound development

The Paris Agreement establishes global objectives and processes to achieve them

The Paris Agreement offers a way forward to address climate change that supports Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 13 on climate action and the broader 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015[1]). Article 2.1 of the Agreement (Box 2.1) includes its three core objectives: mitigate climate change, adapt to its adverse impacts, and make finance flows consistent with low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty. Taken together, these objectives are a basis for global climate action, as achieving them means effectively addressing the drivers and impacts of climate change. This is reflected in Article 3, which refers to Article 2 as establishing the purpose of the Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015[2]).

Article 2.1 also acknowledges that these targets require a global response, thereby implicating a range of actors from governments and international organisations to the private sector, civil society and research organisations, among others.

Article 2.1 states that the aim of the Agreement is to “strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty, including by”:

(a) “Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognising that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;”

(b) “Increasing the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development, in a manner that does not threaten food production;” and

(c) “Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.”

Article 2.2 states that the Agreement “will be implemented to reflect equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances”.

Source: (UNFCCC, 2015, p. 2[2]), Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf

Article 4.1 of the Paris Agreement sets a clear, longer-term target for abating global emissions over the coming decades – the achievement of “a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century” – that is often described as “net zero emissions” (UNFCCC, 2015[2]). The Agreement states that Parties to the Agreement should “aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, recognizing that peaking will take longer for developing country Parties, and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science”. The latest evidence shows that global emissions are not estimated to peak by 2030, let alone by 2020 (World Meteorological Organization, 2019[3]).

Two global mechanisms are key to delivering on the Paris Agreement

Nationally determined contributions

The first nationally determined contributions (NDCs) were prepared by countries in 2015-16 and are due to be revised every five years. NDCs are intended to raise collective ambition to the levels needed to meet the objectives of the Agreement on limiting global average temperature rise (UNFCCC, 2015[4]). However, current NDCs put the world on track to experience between 2.9°C and 3.4°C of warming compared to pre-industrial levels by 2100 (see Chapter 1), and the Agreement’s objectives, therefore, will not be reached (World Meteorological Organization, 2019[3]); (IPCC, 2018[5]). The next round of NDCs need to be stronger.

Long-term low emissions strategies

Article 4.19 of the Paris Agreement calls on Parties to “strive to formulate and communicate long-term low greenhouse gas emission development strategies” (UNFCCC, 2015, p. 2[2]). As these strategies, or LTSs, are to be communicated to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) by the end of 2020, Parties to the Agreement are making major short- and long-term decisions now and over the coming year (UNFCCC, 2016[6]). Chapter 3 examines the challenges posed by current NDCs and LTSs.

Other mechanisms

Developing countries also use various combinations of other UNFCCC processes to determine and communicate their efforts to address climate change, and use these in parallel with other efforts and processes at regional, national and subnational levels that have been initiated and implemented outside the UNFCCC architecture (including under the 2030 Agenda and specifically in support of SDG 13) (UNFCCC, 2019[7]; UNFCCC, 2019[8]). Among the UNFCCC processes are nationally appropriate mitigation actions, national adaptation plans (NAPs), adaptation communications, national adaptation programmes of action, technology needs assessments and technology action plans.

Ownership is fundamental to Paris alignment

Countries’ determination and ownership of their development pathways are practical necessities for effective, long-term action (Box 2.2). Both the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement recognise that countries hold primary responsibility for their economic and social development, and that global aims will be met through national and subnational actions (UN, 2015[1]). As such, they echo the principle of country ownership that the Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation identifies as a requirement for making development co-operation effective and sustainable (OECD, 2012[9]).

Country ownership is a broad principle that can be interpreted in different ways by different actors (Carothers, 2015[10]). For example, some development co-operation activities may focus primarily on supporting country ownership and approval of individual programmes and projects (“rubber stamping”), while others may focus on fostering ownership at a political level among leaders, or among key government and non-government stakeholders through inclusive, participatory methods. While a detailed examination of its multiple dimensions and practical implications is beyond this report’s scope, country ownership is a fundamental development concept and principle that underpins both the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement

Countries included these principles when formulating the universal yet country-driven approaches of the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement. The 2030 Agenda states that the SDGs and their accompanying targets are “integrated and indivisible, global in nature and universally applicable, taking into account different national realities, capacities and levels of development and respecting national policies and priorities” (UN, 2015[1]). The UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement, in Article 2.2, also explicitly recognise that “in light of different national circumstances”, countries have common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities in addressing the challenges of climate change (UNFCCC, 2015[2]). This recognition of developed and developing countries’ different circumstances is particularly important for developing countries that need significant support – for example in the form of funding, technology transfer or capacity development assistance from developed countries – to be able to determine and carry out their priorities on both sustainable development and climate action. This recognition also is consistent with Article 4.4 of the Paris Agreement, which underscores that developed countries “should continue taking the lead by undertaking economy-wide absolute emission reduction targets” (UNFCCC, 2015[2]).

The 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement further acknowledge that inclusive, local input is needed to ensure that approaches to global challenges are both just and robust. The Paris Agreement, in Article 7, states that adaptation is “a global challenge faced by all with local, subnational, national, regional and international dimensions”, and that adaptation action should “be based on and guided by … traditional knowledge, knowledge of indigenous peoples and local knowledge systems” (UNFCCC, 2015[2]). The Agreement also emphasises that national governments should engage with subnational actors to build in-country capacity in a way that fosters these actors’ ownership of activities and effectively responds to countries’ needs. It states that capacity development should be “an effective, iterative process that is participatory, cross-cutting and gender-responsive” (UNFCCC, 2015[2]). The same principles are reflected in the 2030 Agenda, which calls for countries to inclusively review their progress on the SDGs at both national and subnational levels and to draw on contributions from indigenous populations, civil society, private actors and others (UN, 2015[1]).

copy the linklink copied!2.2. Paris alignment can be understood by its four main characteristics

In view of the objectives and mechanisms outlined in the Paris Agreement and the fundamental development principles that complement them, this report proposes four main characteristics of development co-operation that is effectively aligned with the Paris Agreement, namely that it:

-

does not undermine the Paris Agreement but rather contributes to the required transformation

-

catalyses countries’ transitions to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways

-

supports the short- and long-term processes under the Paris Agreement

-

proactively responds to evidence and opportunities to address needs in developing countries.

These characteristics offer a conceptual framework for development co-operation providers to design, implement and continually assess their efforts to align with the Paris Agreement. They are relevant at different levels and over varied timescales. They can guide decisions about the larger-scale strategic changes that are needed across systems and sectors as well as decisions about specific development practices, activities and projects. The extent of change envisioned by the Paris Agreement – at local to global levels and over the span of multiple decades – means that individual development actions and practices need to be consistent with long-term goals (Box 2.3).

The four characteristics of Paris-aligned development co-operation are qualitative and descriptive to allow for the diversity of mandates, priorities, operating models and circumstances among development co-operation providers and developing countries. These characteristics could potentially inform the design and implementation of more quantitatively measurable actions in the future, in line with the temperature goals articulated in Article 2.1 of the Paris Agreement. These characteristics are also complementary; development co-operation providers should prioritise and pursue all of them simultaneously.

To align with the objectives of the Paris Agreement, development co-operation providers need to understand more than just the short-term imperatives of sustainable development in the face of climate change. They should also understand, and support, system-wide transformation over the long term (World Resources Institute/UNDP, 2018[11]).

This may entail, for example, not only using current climate data and vulnerability assessments to design and implement immediate development interventions, but also simultaneously working to strengthen the quality and availability of data and assessment tools to support stronger, evidence-based policies and practices for the long term.

Another example relates to the imperative to anticipate and support more electrified energy end use. In addition to providing financial support for renewable energy-based power systems and technologies, development co-operation can support developing countries to formulate regulatory and policy support measures for greater electrified energy end use in the long term as well as education policies and systems to prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s employment opportunities in a more sustainable energy system.

Characteristic 1: Paris-aligned development co-operation does not undermine the Paris Agreement but rather contributes to the required transformation

Development co-operation activities that are Paris-aligned not only do no harm to effective action on climate change. They also make a positive contribution to the system-wide transformation needed to achieve low-emissions, climate-resilient societies, as discussed in detail in Chapter 1. Both the 2030 Agenda and the objectives in Article 2.1 of the Paris Agreement set out an ambitious vision for countries to fundamentally transform their development. It is insufficient for development co-operation providers to focus on meeting a minimum standard of doing no harm by avoiding decisions and activities that undermine the Paris Agreement. A systemic shift is only possible if all countries comprehensively prioritise and pursue the required transformation in all of their decisions about their growth and development, across all sectors and activities, and with a consistent emphasis on inclusion and leaving no one behind (New Climate Economy, 2018[12]).

Development co-operation providers are important agents for supporting the transition away from outdated frameworks and activities that add to the existing mitigation and/or adaptation burden. Their mandate is to actively contribute to the type of development progress that is needed in the 21st century. To be Paris-aligned, all development co-operation activities – including those without a designated climate objective – should be low-emissions and climate-resilient. While it is not necessary for all development co-operation activities to include active climate objectives, it is critical that their underlying assumptions, conditions and objectives be comprehensively adapted to support a systemic approach to achieving low-emissions, climate-resilient development.

The Paris Agreement, in Article 3, acknowledges the need to raise ambition to adequately address climate change, committing that the Parties shall undertake and communicate ambitious efforts so that the Agreement is effectively implemented (UNFCCC, 2015[2]). The stark reality, as discussed in Chapter 1, is that the collective commitments outlined in current NDCs are insufficient to limit temperature rise in line with either of the objectives of Article 2.1, i.e. to well below 2°C or to 1.5°C. In parallel with these inadequate commitments, global progress across sectors on both climate change mitigation and adaptation has been limited since adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015 and its entry into force in late 2016. Global energy-related CO2 emissions reached a historic high in 2018, growing by 1.7% from 2017 (IEA, 2019[13]). This was the highest rate of annual growth since 2013, and demonstrates the massive gap between current emissions and global mitigation objectives (IEA, 2019[13]). Similarly, on adaptation, a major gap persists between current efforts and the levels of coherent policy commitment and financing that are needed across many sectors. The United Nations (UN) Environment Programme noted in 2018 that fewer than half of 162 countries1– both developed and developing – had in place integrated frameworks for holistically addressing climate change adaptation (UNEP, 2018[14]). Moreover, available adaptation finance remains far less than the latest global estimates of the costs of adaptation and far below the needs identified in current NDCs (UNEP, 2018[14]).

As Chapter 1 outlines, the world is not yet on track to achieve the fundamental transformation of socio-economic systems that is needed for low-emissions, climate-resilient societies (OECD/World Bank/UNEP, 2018[15]; UNFCCC, 2019[16]). Chapter 3 discusses further the challenges and limitations of efforts to date.

Characteristic 2: Paris-aligned development co-operation catalyses countries’ transitions to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways

Development co-operation that is Paris-aligned acts as a catalyst for developing countries’ inclusive transformation (as described in Characteristic 1). This means deploying finance strategically and engaging in policy support and capacity development (see Section 2.3) to trigger broader change, in particular change led by partners and other actors. In this sense, Paris alignment requires providers to plan and implement individual projects with a view towards creating a more conducive environment for the transformation while also helping to ensure that activities support the groups and communities in developing countries that need support the most (Box 2.4). This reflects what the Paris Agreement calls the “intrinsic relationship” between “climate change actions, responses and impacts” on the one hand and “equitable access to sustainable development and eradication of poverty” on the other (UNFCCC, 2015[2]).

Given the mandate of development co-operation and the limited volumes of available development finance, providers need to use development finance to support interventions that maximise development impact. Catalysation is vital. Concessional development finance, in particular, provides significant flexibility to beneficiaries and enables them to operate in higher-risk environments and activities. It is especially critical that such finance be allocated in a way that is targeted, strategic and uses resources efficiently for optimal impact, including by catalysing further action.

While development finance is a relatively small resource, it is the major source of international climate finance flows to developing countries (OECD, 2015[17]). Development co-operation providers need to increase the volume of development finance resources that are available to support Paris-aligned development. As a first step, they should meet their existing commitments and ensure that these commitments are Paris-aligned. Among these are developed countries’ long-standing commitments to continue their existing collective mobilisation goal of increasing the joint mobilisation of climate finance to developing countries to USD 100 billion annually through 2025, and to set a higher collective goal before this date (UNFCCC, 2016[6]), recognising that the need to scale up dedicated climate finance will persist over the coming decades (UNFCCC, 2018[18]).

At the same time, it is clear that development finance alone cannot deliver or account for the full extent of the transition that needs to happen. Where possible, catalysation should support the reduction or phasing out of development finance in sectors, markets, locales or categories of interventions when adequate flows of other financing and funding resources are present. Catalysation includes direct finance mobilisation as well as support for the systems that underpin resource flows in countries, including those that support private financial markets in particular and also fiscal and public financial management and revenue systems in developing countries (Box 2.4). The objectives set out in Article 2.1 demand greater mobilisation and shifting of all financial flows to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement. A strategic focus on using development co-operation to catalyse increased resources across a broad range of financial flows supports Article 2.1c, which calls for making all financial flows consistent.

In this report and across the broader work of the OECD, catalysation refers to activities that help to create a more conducive environment for meeting a certain objective by triggering changes led by other actors. Catalysation can involve the use of development finance to crowd in commercial capital through programmatic approaches and market creation (such as the Renewable Energy Independent Power Procurement Programme in South Africa), for example, or support to capacity development for local governments to unlock commercial resources for building climate-resilient urban settlements. Mobilisation is a subset of catalysation and refers to finance transactions wherein one form of financing unlocks another that otherwise would not have been available. Notably, mobilisation is specific to the context of individual transactions, and maximising mobilisation is not a goal in itself but should instead be pursued in order to meet development objectives.

In recent years, focus has increasingly centred on mobilising private finance for sustainable development, including in climate-sensitive sectors, with an emphasis on blended finance.1 A shift away from the traditional focus on financing the private sector and towards mobilising private finance is crucial to effective climate action in line with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Such a change requires greater mobilisation of specific development finance transactions and increased catalytic ambition over time (OECD, 2018[19]). Effective catalysation is consistent with a trend of increasing mobilisation of commercial finance and decreasing use of development finance in a given geographic area or sector, with the eventual goal being an exit from development finance. While mobilisation at the transaction level holds significant potential and is important, the catalytic role of development co-operation for aligning financial flows with low-emissions, climate-resilient development is broader, as it aims beyond the transaction level to have a wider impact. The OECD Blended Finance Principles reflect a broader perspective, referring to the need for local financial market development and promotion of a sound enabling environment (OECD, 2018[20]), two goals for which development co-operation providers’ support for capacity development and engagement at the policy and regulatory level is key.

← 1. Blended finance refers to the strategic use of development finance for the mobilisation of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries. See (OECD, 2018[19]) at https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264288768-en

Characteristic 3: Paris-aligned development co-operation supports the short- and long-term processes under the Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement establishes short- and long-term processes to achieve its objectives for addressing climate change in the 21st century and beyond. Paris-aligned development co-operation helps countries to increase their ambition over time, in line with the objectives presented in Article 2.1 of the Agreement, by supporting the development, financing and implementation of NDCs and LTSs. In many developing countries, development co-operation providers have an equally important role to play by supporting the integration of other climate action processes that countries are pursuing in parallel, including under and outside of the UNFCCC architecture, including at the subnational level (see Section 2.1).

Development co-operation should also help countries to link Paris Agreement processes with other overarching development and sectoral plans. Action on climate change cannot be effective when it is disconnected from countries’ broader visions and decision making on development, including efforts to achieve the SDGs (World Resources Institute/UNDP, 2018[11]). One example pertains to adaptation – countries often develop policies by sector, and both developed and developing countries commonly formulate national adaptation strategies that they pursue through more detailed national and sectoral plans (UNEP, 2018[21]); (New Climate Economy, 2018[12]). Immediate and mid-term plans provide crucial policy signals that create the enabling environment for forward-looking decision making by both public and private actors, and therefore have the potential to determine the effectiveness of both NDCs and LTSs (World Resources Institute/UNDP, 2018[11]). Development co-operation providers already help developing countries to integrate climate processes into development planning. This integration is vital for establishing the right policy settings, realising co-benefits by connecting efforts to achieve multiple SDGs, creating project pipelines that support ambitious climate action, and mobilising new sources of finance (including the unlocking of private capital).

Development co-operation providers need a concerted, long-term focus if they are to plan and allocate resources and encourage institutional change in a way that supports the transformation to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways. As Chapter 1 illustrates, LTSs that adequately incorporate the necessary transitions in countries are critical for reducing the risks of carbon lock-in and embedded climate vulnerability (Ross and Fransen, 2017[22]).

Development co-operation providers should support countries to connect the short-term and longer-term policy imperatives of climate change and sustainable development. They should also support countries to address the inconsistencies that may arise if climate change and sustainable development are pursued in isolation, as separate agendas. Where greater ambition or coherence between approaches is needed, development co-operation providers should support and work with developing countries to identify and take up opportunities to enable a smooth transition, leveraging their concessional finance resources and long-standing role in facilitating the transfer of technology. This is particularly applicable in developing countries with limited capacities and special needs, and which require support to develop coherent short- and long-term approaches through means such as continuous capacity development, peer learning and collaboration programmes (Ross and Fransen, 2017[22]). Chapter 3 examines some of the key challenges, considerations and priorities for development co-operation in promoting ambitious NDCs and LTSs in the context of sustainable development.

Characteristic 4: Paris-aligned development co-operation proactively responds to evidence and opportunities to address needs in developing countries

Paris-aligned development co-operation proactively responds to continually emerging and evolving evidence on the pace and scale of climate change and its impacts; to identified needs and special circumstances within specific communities and sectors (consistent with Article 2.2 of the Agreement); and to opportunities and solutions (including technologies, innovation and good practices) for addressing these challenges. New information, lessons and opportunities continue to emerge as countries develop. Development co-operation should be attuned and responsive to support countries’ self-determined development pathways while also facilitating the transformation to low-emissions, climate-resilient societies that is needed to achieve the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.

Development co-operation can only facilitate this required transformation if providers commit to using up-to-date information on both climate change and sustainable development progress to inform their institutional priorities and guide their work with developing countries. The Paris Agreement sets objectives that countries will pursue over multiple decades. It is self-evident, then, that Paris alignment is not a single or static task; rather it is a continuous and dynamic process in which providers should refer to the latest evidence to regularly assess and adjust their efforts and take up new opportunities that offer the greatest impact potential (UNFCCC, 2015[2]; World Resources Institute/UNDP, 2018[11]). Such an approach supports the ratchet mechanism of the Paris Agreement and the process for assessing collective progress towards achieving the purpose of the Agreement and its long-term goals. The Agreement states that this assessment process, which it terms the global stocktake, should be done “in the light of equity and the best available science” (UNFCCC, 2015[2]).

The direct relationship between action on climate change and sustainable development means that providers can be crucial pioneers in their Paris-aligned development interventions by supporting developing countries to identify opportunities, respond flexibly to emerging evidence, and work towards Paris alignment in their development and sector strategies. This includes gathering and using not only the latest of evidence of good practice but also evidence from different sources and at different scales – including the best available science on climate scenarios, impacts and emissions trajectories as well as knowledge from traditional, emerging country- and local-level sources on vulnerability, risks and potential solutions. Development co-operation providers’ institutional incentive structures, operations and practices offer catalytic potential, so it is especially important that these are flexible and able to adapt to address existing and emerging constraints. Providers that support Paris alignment focus on the accelerated identification, deployment and scaling of innovation and new solutions (including technologies and practices stemming from local innovation) and are ready to adjust their own operations to the changing approaches or products that these solutions require.

The climate strategy of the European Investment Bank (EIB) – the first version of which was approved two months before the Paris Agreement in 2015 – is an example of a plan that has successfully provided for institutional responsiveness to new evidence and opportunities. The strategy commits EIB to extending its coverage of sector policies and to regularly updating policies in view of sectors’ climate sensitivity and the need to account for “the most recent scientific knowledge and available best practice” (European Investment Bank, 2015[23]). The strategy further provides for the revision of sector policies with reference to shifting economic and regulatory conditions, as well as “transition pathways towards a maximum 2°C global temperature rise”2 (European Investment Bank, 2015[23]). In 2019, these provisions were a basis for informing a new energy lending policy that commits the EIB Group to aligning all financing activities with the goals of the Paris Agreement from the end of 2020, and to end EIB financing for fossil fuel energy projects from the end of 2021 (see Section 2.4) (European Investment Bank, 2019[24]).

Responding to evidence inherently entails also responding to existing and future needs for support within countries at both the national and subnational levels. Development co-operation providers already significantly contribute to recognising and responding to needs and opportunities within developing countries. This knowledge allows them to target their interventions and help to protect populations facing the greatest vulnerability. This role is also recognised throughout the Paris Agreement including in Article 2.2, which notes the differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities of actors in the light of different national circumstances (UNFCCC, 2015[2]).

Development co-operation providers best support developing countries’ transformation by being responsive to evidence and needs and working with these countries to improve access to vital information and evidence and identify emerging opportunities, experience, innovation and needs.

The four characteristics of Paris alignment work in tandem

While not exhaustive, these four characteristics highlight important considerations for development co-operation providers in interpreting and prioritising Paris alignment. Taken together, they synthesise what Paris alignment means for development co-operation and underscore that providers will contribute positively to the needed transformation by making the most of their resources, connecting with and involving the right actors, and using established mechanisms to support climate action and raise ambition in line with the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

copy the linklink copied!2.3. Paris alignment means supporting climate action through financing, policy support and capacity development

The four characteristics of Paris-aligned development co-operation (Section 2.2) apply to development co-operation actors that pursue their mandate and work through three levers: financing, which is the provision of financial resources that address financial gaps and bottlenecks to enable development interventions by public and private actors; policy support to developing countries to identify and advance policy and regulatory measures that create and sustain an enabling environment conducive to the achievement of development goals; and capacity development, which means supporting the development and enhancement of the ability of people, organisations and society as a whole to manage their affairs successfully with the required information, knowledge, skills and technology (Figure 2.1).

To support developing countries’ transition towards low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways, development co-operation providers need to use all three levers:

-

Financial resources provided should be consistent with the adaptation and mitigation needs of sustainable development.

-

Development co-operation providers should support enabling policy and regulatory frameworks for the transformation of economic and social sectors in line with low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways over time.

-

Development co-operation providers should support capacity development as an essential element in undertaking practical, country-driven and participatory steps towards low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways.

In practice, development co-operation interventions almost always involve more than one lever. Policy and regulatory action is contingent on the capacity for policy development and implementation, for instance. Likewise, financial support is not merely provided to fill a financing gap but can be paired with technical assistance to support capacity to implement and sustain associated new technology. Policies shape public actions as well as investment, in that policies determine the scope and frame for private economic actors operating in a country, both domestic and international, that have the ability to unlock and direct funding and finance.

At the same time, different types of actors in the international development system have different approaches, roles and underlying business models. These are relevant when considering Paris alignment, and are discussed in this section, according to a stylised categorisation, as donor governments, development banks and bank-like institutions, non-bank providers of development co-operation, and specialised agencies and funds (including both those with and without a climate focus).

The stylised institutional models are less clear-cut in the real world, and it is often difficult to make categorical distinctions between the support that development banks, development finance institutions (DFIs) and development agencies provide across the different levers of financing, policy support and capacity development. Development banks, for example, often support capacity building in partner financial institutions in developing countries as an accompanying measure to the provision of green credit lines (Gietzen, 2018[25]). Donor countries use the financing lever in a complementary manner, for example issuing financial compensation for forest conservation efforts to reflect the value of forest ecosystems for the climate and, in tandem, supporting developing country partners with the legal and institutional framework for sustainable forest management and biodiversity conservation (Government of Norway, 2018[26]). Moreover, many multilateral development banks (MDBs) engage in policy-based lending to developing countries, such as by targeting policy reform for renewable energy promotion (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2018[27]). With specific reference to the Paris Agreement, MDBs and members of the International Development Finance Club (IDFC)3 committed to a variety of actions in 2017, such as supporting institutions to translate NDCs into policies, investment plans and bankable projects (Asian Development Bank, 2017[28]). Donor governments raise resources, set the mandates, and define the authorising environment and policy priorities for development co-operation.

Donor governments are defining actors of the international development co-operation system. They represent the sovereign peer and partner to developing country governments as the basic fundament for development partnerships and counterpart for policy dialogue. Individually, donor governments define bilateral development co-operation; together with developing countries, they collectively shape and sustain the multilateral development architecture.

Donor governments raise the budgetary resources that underpin development co-operation and finance. They provide the funds for grant spending and highly concessional instruments, and raise resources through the capitalisation of development banks and institutions with a bank-like business model.

Donor governments also set the mandates for bilateral development co-operation and determine the priorities, strategies and resource allocations to achieve these mandates. Donor governments have either direct execution capacity or they are responsible for the governance and oversight of the institutions and organisations charged with the implementation of technical or financial assistance. They also are responsible for addressing potential conflicts between policy goals in different areas. Through their shareholding and governance role and their substantial contributions and funding, donor governments also steer the strategies and policies of multilateral development institutions and define their overall authorising environment.

Importantly, an expanding range of countries are able to actively, and at increasing scale, contribute to the international development effort. Historically, members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) were predominant in international development. Increasingly, countries that are not DAC members – including some that are themselves developing countries – are playing an important role and making important contributions, both as providers of technical and financial co-operation to other countries and as financial supporters and sponsors within the multilateral system.

Development banks and development finance institutions have a primary focus on non-grant instruments typically used for infrastructure financing

Development banks and DFIs include multilateral and bilateral institutions of vastly different sizes, financial assets and operational focuses. While heterogeneous, development banks and DFIs share a fundamental, defining feature – their business model is that of a financial institution, which means that their operations need to generate the financial returns to cover their operating expenditure and funding costs. As such, and by necessity, the core operations of these institutions rely on non-grant, repayable financial instruments. Once capitalised, development banks and DFIs can continue to operate and recycle their financing, although in the absence of additional grant or concessional funding, they are constrained in their ability to finance highly concessional activities with high financial risks.

In addition to financing, development banks and DFIs provide capacity development and policy support. To do so, they also receive grant resources from their shareholders and additionally use these resources to offer highly concessional financial terms to the poorest countries and countries with the least access to market finance. MDBs, for example, engage in these activities through their concessional windows. While development banks and DFIs are distinctly financing institutions, they also are often a channel of choice for donors to engage in capacity-building policy support, due to their substantial and unique expertise, skill set, and delivery capacities

Nonetheless, it is useful to differentiate development banks from DFIs according to their partner entities and use of financial instruments. Very generally, bilateral and multilateral development banks pursue both public and private sector operations. Public sector operations of bilateral banks and MDBs provide debt finance and, to a lesser degree, grants. With a view to their partner entities, these institutions work largely with the public sector; private sector operations of development banks have a specific mandate to engage with the private sector. Many DAC members also have bilateral DFIs. DFIs and private sector operations of development banks provide equity, loans, guarantees and insurance, for example to private sector infrastructure projects, and most often do so at non-concessional terms.

Development banks and DFIs serve as important channels for infrastructure finance to developing countries, and therefore have a direct impact on low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways (Crishna Morgado and Taşkın, 2019[29]). For development co-operation providers and development banks, particularly DFIs, investments in hard infrastructure, i.e. physical assets, have taken centre stage in Paris alignment to date. Beyond the provision of finance for infrastructure-related investment, however, their efforts – for example, the mobilisation of additional resources and provision of finance to promote specific business models and technologies – have an impact on developing countries’ transition to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways.

Development agencies are critical to facilitating the transformation that is needed

Non-bank development co-operation providers, hereinafter called development agencies, deliver grant-based development co-operation across a range of sectors and policy areas, relying on recurrent funding from budgetary appropriations and donor contributions. Very generally, development agencies focus on capacity development, technical co-operation and support to policy reform. With few exceptions, the financial volume of these activities usually does not reach the scale of development co-operation in the form of debt instruments such as sovereign lending or project finance for hard infrastructure. As a rule, development agencies are comparatively more focused on activities that do not lend themselves to non-grant, i.e. repayable, assistance that is typically associated with hard infrastructure.

Policy support and capacity building usually do not have major direct climate outcomes per se, for example in the form of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced or avoided by a financed power plant. However, policy support and capacity development can have significant impacts on developing countries’ enabling environment and the resulting public or private investment choices, as well as on their capacities to successfully undertake the transition to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways. Paris alignment is much less understood and developed with respect to policy support and capacity development. But alignment across all three levers is essential for development co-operation to effectively support low-emissions, climate-resilient development (see Section 2.2).

Specialised agencies and vertical funds need to integrate the climate dimension into their policy and sector focus

Specialised agencies and vertical funds are institutions with a focused mandate on a specific development priority or challenge. In the climate change area, some notable examples include the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the Adaptation Fund and the Global Environment Facility (GEF), although the latter has a somewhat broader mandate. The International Renewable Energy Agency and the Global Green Growth Institute can also be included in this category.

Specialised agencies and vertical funds concentrate expertise and substantive capacity on climate change, although they tend to have less implementing capacity on the ground in developing countries compared to development agencies and development banks. Their individual models and mandates vary. The Adaptation Fund has an exclusive focus on adaptation and resilience activities. The GCF mandate relates to both adaptation and mitigation, whereas GEF’s remit covers a broader range of environmental priorities including but not limited to climate change. All operate through accredited entities that develop and have execution responsibility for selected programmes and activities. Their public counterparts include many traditional development finance actors, both international and national, that invariably link them back to the broader institutional architecture for international development.

The specialised institutions with a dedicated mandate for addressing climate change do not operate with a bank-like business model, although they may use financial instruments such as loans, equity, guarantees and grants. In doing so, they have a greater ability to take on financial risk across their portfolio of activities than do bank-type institutions, because the core resources that sustain their operations do not rely on these financial activities and instead are provided mainly through regular replenishments. At the same time, the financial scale within which they can take on risk is more limited than that required for full project finance of large-scale infrastructure.

Many other specialised agencies exist to address specific development priorities outside the area of climate change. Most are international bodies, among them the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and specialised UN agencies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization and the UN Industrial Development Organization, although some, like the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, are bilateral institutions. Like specialised funds in the climate change space, these agencies often have unique expertise and resource capacities, and they play a systemic role in their focus area, including to identify and understand new and emerging challenges to their policy mandates. One of these challenges is climate change, given its impact on development, and these actors need to respond to it. While the immediate, direct exposure to climate change is well understood in sectors such as agriculture, stronger awareness and action are also required for development priorities that have so far been only marginally associated with climate change such as health, as climate change is liable to affect the entire delivery system for health in many developing countries (UNEP, 2018[14]).

Paris alignment of development co-operation requires a stronger focus beyond the financing lever

Measures of Paris alignment and analytical work have so far largely focused on the financing lever and emissions reduction, as indicated by a survey conducted for this report, commitments made by providers and a growing body of literature (IDFC, 2018[30]; Larsen et al., 2018[31]; African Development Bank et al., 2018[32]) (Germanwatch/NewClimate Institute, 2018[33]). Focus on direct financing, and particularly direct financing of hard infrastructure, is clearly relevant and important. Across developing countries, the investment gap for sustainable infrastructure is estimated at USD 4 trillion annually until 2030, equivalent to two-thirds of global infrastructure investment needs (Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, 2016[34]). The goals of the Paris Agreement require a fundamental transformation of existing infrastructure (IPCC, 2018[5]). This should be reflected in the policies and factors development banks and DFIs look at in determining how and why to finance infrastructure projects and the technologies they support through this financing.

Nonetheless, the overall share of development finance in direct financing of infrastructure is relatively small, at 6-7% of total infrastructure spending in developing countries (OECD, 2015[35]). Moreover, direct financing of infrastructure investments through development finance is much more important in least developed and low-income countries than it is in middle-income countries. This difference reflects their greater aid dependency and that alternative sources of infrastructure finance are less available and accessible. It also points to the need to unlock alternative sources of development financing as income levels increase (Sy and Rakotondrazaka, 2015[36]).

Policy reform and capacity strengthening levers have an important catalysing role for climate and development financing. Against this backdrop, the policy and capacity levers assume central importance, including with regard to the mobilisation and re-directing of further funding and finance. For example, much of the advancement of renewable energy has been achieved due to effective policies that provided a level playing field with fossil fuel-based energy sources, a basic precondition for the financial viability of such investments in the first place (IRENA, 2019[37]) (IRENA, International Energy Agency and REN21, 2018[38]). In developing countries, development agencies have supported such policy reform and are increasingly taking a systems approach to support developing countries to leapfrog inefficient and polluting heating, cooling and transport systems.

In addition to supporting these emission-critical sectors, policy reform can support the establishment of financial systems and fiscal policies for climate action that will be needed to mobilise domestic and international and public and private financing for sustainable development. While not directly responsible for climate policy and action, fiscal policy and the way financial systems are regulated and governed can have significant effects on climate outcomes. These can be direct effects, e.g. through fossil fuel subsidies, or reflected in the way climate risks are accounted for in financial regulation for due diligence, which has immediate and significant impacts on the performance and viability of a given project (OECD, 2018[39]). Beyond this, indirect effects can be important, for example through inadvertent technology bias in corporate income taxation (Dressler, Hanappi and van Dender, 2018[40]). Fiscal policy and financial regulatory frameworks are therefore powerful determinants in efforts to transition to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways.

Policy frameworks need to be matched with essential capacity to provide an enabling environment for climate action. Developing and developed countries need stronger capacities at different levels to effectively undertake the transition to low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways. While there is no universal definition of these levels, capacities can be required at the system, institutional, individual and network level (GIZ et al., 2012[41]). Development agencies have traditionally supported capacities across these levels. For example, they support municipalities to design and implement climate change action plans. Development agencies also facilitate exchange among industry and business associations, financing institutions, and governmental entities to promote conducive partnerships for the implementation of mitigation measures that go beyond those supported directly through individual technical co-operation projects.

Policy support and capacity development are critical building blocks in Paris alignment. While development co-operation providers can only facilitate the processes of establishing and strengthening enabling environments, they can extend their impact beyond individual measures by informing and supporting the rules of the game for economic and financial and public and private actors and by building these actors’ capacities. All of these can have a beneficial, catalytic effect. Therefore, it is critical that development agencies integrate the objectives of the Paris Agreement across their activities.

Given that Paris-aligned development co-operation can take the form of financing, policy support and capacity development, separately or in tandem, these efforts will require different approaches, tools, monitoring and reporting. The three levers need to be used in improved ways that sufficiently incorporate climate objectives and facilitate sustainable development. For example, triangular co-operation, whereby providers of development co-operation facilitate initiatives between two developing countries, can be used as a tool for technical exchange that furthers various environmental objectives (OECD, forthcoming[42]). More information and evidence on emerging good practice approaches, initial lessons learned and challenges to Paris alignment are needed across varying scopes and domains of development co-operation.

Delivering effective development co-operation against existing and future threats of climate change will require a more systematic and scaled-up effort to provide development finance that consistently supports low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways. A systematic and accelerated effort will also be needed to embed climate considerations in the policy and capacity levers and into endeavours to catalyse financial flows more broadly.

copy the linklink copied!2.4. Paris alignment means inclusion of climate action in development co-operation strategies, programmes and operations

Paris alignment involves different approaches and instruments that can be used alone or together to support developing countries to strengthen the global response to the climate crisis. Development co-operation providers have developed an array of tools to ensure that development co-operation activities support climate and other environmental aims. Such tools are essential for institutionalising and implementing commitments made under the Paris Agreement. Identifying and examining providers’ most commonly used tools and approaches provide a baseline for strengthening efforts towards Paris alignment and ensuring that providers are supporting climate objectives and, by extension, sustainable development.

Three themes emerge from actors’ efforts to conceptualise and interpret Paris alignment. First, these efforts reflect a growing understanding that climate action belongs at the heart of sustainable development, fully integrated into strategies, theories of change and programming. This understanding places the Paris Agreement within the broader strategic context of sustainable development. Second, many approaches emphasise that Paris alignment means increasing the mobilisation of climate finance while concurrently ensuring that all activities, whether or not they are financed via climate financing, consider and incorporate the objectives of the Paris Agreement. Third, emerging conceptions of alignment combine the same bottom-up, country-oriented processes and top-down, global approaches that are outlined in the Paris Agreement.

This section explores the main emerging approaches, instruments and mechanisms of Paris alignment that development co-operation providers are using. It draws on a survey of DAC members and multilateral development co-operation providers, direct engagement and interviews with those providers, and a broader literature review. The section also reviews examples of how selected actors in the development community are interpreting what Paris alignment means – concretely, through initiatives and approaches – and how it can be more clearly centred in development co-operation.

Linking climate action to sustainable development requires alignment across development finance and associated activities

Aligning development co-operation with the objectives of the Paris Agreement preserves development progress already made and helps to achieve the SDGs. Climate action and sustainable development are inseparable, as is put forth in Article 2.1 of the Agreement. As sustainable development is the primary aim of development co-operation, the impacts of climate change need to be taken into account in pursuing this objective. These include all areas that substantially affect, or are substantially affected by, climate change either directly or indirectly, such as investment, taxation, fiscal systems, energy, agriculture and sustainable food production, employment, transport, and regional and urban policy. In this way, an overarching understanding can be built of what Paris alignment entails for development co-operation, and which is relevant to most policy areas and sectors in developing countries.

Intertwining climate action and sustainability has implications for how development co-operation conceives of financing and respective mandates. Development co-operation providers have begun to make commitments to align with the Paris Agreement, and this reflects an evolving interpretation and conceptual shift.

Recent analysis shows the need for what Larsen et al. (2018[31]) call a “Paris Alignment Paradigm” that supports Article 2.1c and would represent a shift from the current “Climate Finance Paradigm”. Climate financing currently focuses on defining, tracking and maximising financing towards climate change mitigation and adaptation. The Paris alignment paradigm would alternatively ensure consistency with the Paris Agreement across portfolios, pipelines and activities in addition to maximising climate finance volumes. While this literature focuses on MDBs and DFIs, the significance of the Paris alignment paradigm applies across development co-operation. Its associated framework (Figure 2.2) applies globally to all activities across countries and organisations. This paradigm also highlights a need for all development co-operation providers and developing countries to pursue Paris alignment using the levers of finance, policy support and capacity development and a need to carefully track and report on how finance flows are shifting towards low-emissions, climate-resilient development pathways.

Development actors have various approaches to alignment

Bilateral development co-operation providers have started to purposefully define Paris alignment as a core dimension of financial decision making, and they have made commitments towards alignment. One example is the French Development Agency (AFD). Having committed to making its activities “100% Paris Agreement-compatible”, AFD created what it terms a “sustainable development analysis” mechanism (AFD, 2018[43]; AFD, 2017[44]). This mechanism defines six operational dimensions for sustainable development, including a two-part climate change dimension on the “transition to a low-carbon pathway” and “climate change resilience”. This approach situates climate action at the heart of sustainable development along with five other dimensions of sustainable development (AFD, 2018[43]): sustainable and resilient economic growth; social well-being; gender equality; biodiversity conservation and management of environments and natural resources; and project impact sustainability and governance.. AFD also defines the scope of climate action at the country level through respective NDCs. This strengthens consistency with country-led climate action but requires emphasis on the role of development co-operation in raising ambition and ensuring that NDCs themselves are Paris-aligned. Box 2.5 outlines the AFD approach.

The French Development Agency (AFD) is one of the first institutions to commit to an alignment-related goal in its overarching strategy. In 2017, AFD announced its ambition to ensure all activities are “100% Paris Agreement-compatible”, i.e. aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement (AFD, 2017[44]). This commitment originated in the French government’s national Climate Plan, published in 2017, and is the first of five goals in the AFD Group’s corporate strategy for 2018-22 (AFD, 2018[43]). While the strategy reiterates AFD’s continued target of 50% of climate finance in overall financing, it also represents a shift to the broader goal of ensuring that all operations are consistent with the Paris Agreement objectives while also supporting developing countries to prepare long-term strategies for low-carbon and climate-resilient growth.

AFD’s strategy aims to support developing countries to achieve the SDGs by focusing on what it terms “transitions” in sectors and thematic areas that integrate climate and other sustainability considerations. For example, AFD’s support for the energy transition focuses on decarbonisation alongside the need for affordable and reliable energy in developing countries. In line with such a transition, AFD will support electricity and transport policy reform, increase investment in renewables and power distribution, and promote energy efficiency. In the strategy, AFD also commits to not invest in coal or nuclear power.

AFD also is implementing the commitment to 100% compatibility by integrating specific alignment-related criteria into the Sustainable Development Analysis framework that it applies to all operations. Alignment is assessed not only from the point of view of promoting low-carbon development, but also resilience and adaptation. The approach used in the framework is qualitative and embedded in national efforts; consistency with national climate policies is one of the criteria use for assessing alignment. The AFD’s initial experience of implementing this approach has shown its utility in supporting a wider discussion on alignment with project teams.

Source: (AFD, 2018[45]), Towards a World in Common - AFD Group 2018-2022 Strategy, https://www.afd.fr/sites/afd/files/2018-09-04-05-09/afd-group-strategy-2018-2022.pdf

The Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO) is an example of an actor approaching climate mitigation as fundamentally tied to the science-based temperature goals set out in Article 2.1 of the Paris Agreement (Box 2.6). Actors that are not development co-operation actors are taking similar approaches. The Science Based Targets initiative, for instance, supports companies to develop corporate targets for reducing their emissions that are consistent with the temperature goals of the Paris Agreement (Science Based Targets, 2019[46]). To accomplish this, the initiative proposes methods such as defining a carbon budget and using emissions scenarios and allocation approaches to make companies’ approaches credible and rigorous (Science Based Targets, 2019[46]). The initiative’s aim – to help private sector actors to make their activities consistent with the global temperature goals in the Agreement – reflects the growing recognition that Paris alignment is a priority for non-government actors and a critical part of the global effort to meet the objectives of Article 2.1. Science Based Targets also emphasises that companies should devise targets that cover up to 15 years of activity while also developing long-term targets for 2050 (Science Based Targets, 2019[46]). This approach is mitigation-centric and does not explicitly support companies to achieve climate resilience or adaptation aims, but instead concentrates support into high-emitting sectors when Paris alignment requires shifts across portfolios.

The Netherlands Development Finance Company (FMO) focuses on financing the private sector in developing countries. In terms of portfolio size, it is the largest member of the association of European Development Finance Institutions. In 2017, as part of a new Sustainability Policy, FMO committed to using its investments to contribute towards the goals of the Paris Agreement, specifically to limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C and preferably to 1.5°C (FMO, 2019[47]). This commitment is contained within the FMO strategy, which highlights SDG 13 (climate action) as a key priority. It also reflects the approach of FMO to sustainability, which incorporates an exclusion list (e.g. on coal); screening for environmental, social and corporate governance risks; and proactive promotion of sustainable finance using a green label. This green label identifies investments that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote natural capital and support adaptation, and it corresponds with internal annual targets. FMO accounts for greenhouse gas savings from these investments, and an independent panel within FMO screens investments to assess whether the benefits of the investment are aligned with FMO’s green label criteria.

For FMO, delivering on SDG 13 translates into climate adaptation, climate mitigation and climate finance mobilisation.

Government funds and the Dutch Fund for Climate and Development (DFCD), which FMO manages, are the main source of funds for FMO’s adaptation efforts. The DFCD aims to achieve climate-resilient economic growth in least developed countries by adopting what it calls a “landscape strategy” for deal origination and execution. DFCD investments seek to improve the well-being, economic prospects and livelihoods of vulnerable groups – particularly women and children – and to enhance the health of critical ecosystems including water basins, rivers, tropical rainforests, marshland and mangroves.

In terms of mitigation (i.e. reducing emissions), FMO uses the 1.5°C pathway as a benchmark to steer investments towards renewable energy, energy efficiency, and negative-emitting transactions like reforestation and climate-smart agriculture. FMO also uses a 1.5°C scenario and corresponding carbon budgets as a starting point for assessing alignment of its portfolio with the Paris Agreement (FMO, 2019[47])(FMO, 2019[47]).

As a first step, FMO’s so-called “fair share” of the global carbon budget and corresponding pathway are assessed using global data on OECD and non-OECD countries. Second, FMO compares the annual emissions footprint of its finance against the point where it should be along a pathway towards limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C. This goes beyond calculating and reporting greenhouse gases avoided as a result of an investment and towards an approach that steers overall portfolio allocations and investment decisions based on an absolute emissions footprint of FMO’s portfolio. FMO carried out an assessment of new investments in 2015 and 2016 as a way of piloting this approach. It found that annual financed emissions were within its emissions allowance, largely due to a large share of investments being in renewable energy and other low-carbon sectors.

Source: (FMO, 2018[48]), Absolute GHG Accounting Approach for Financed Emissions, https://www.fmo.nl/l/en/library/download/urn:uuid:a85bc36b-feb5-4321-9a49-4dd3dd00bfb8/absolute+ghg+accounting+approach+ final+for+consultation+oct+2018.pdf.

Another approach to Paris Alignment is exemplified by the United Kingdom, which has embedded its commitment within broader government policy. In July 2019, the United Kingdom committed to align its official development assistance (ODA) with the Paris Agreement in the government’s Green Finance Strategy, which is designed to align private sector financial flows with clean, environmentally sustainable and resilient growth supported by government action (Government of the United Kingdom, 2019[49]). The strategy specifies that aligning ODA includes pricing carbon during the assessment of relevant bilateral development programmes and ensuring that fossil fuel support aligns with temperature goals and transition plans, as well as a commensurate response for addressing climate risks. The strategy also highlights a need to ensure that development activities do not undermine the ambition of country NDCs and adaptation plans in support of fundamental processes of the Paris Agreement. This approach translates the objectives in Article 2.1 into a top-down commitment for development co-operation activities, and also recognises the need to work with developing country governments to make their contribution towards the Paris Agreement goals.

Multilateral development co-operation providers have also committed to define alignment across financing activities and have started to do so. At the 2017 One Planet Summit, MDBs and the IDFC committed to align financial flows with the Paris Agreement. One aspect of this is the commitment by MDBs and IDFC members to redirect financial flows in support of low-emissions, climate-resilient development in developing countries and to develop processes and tools to put commitments into practice. They also expressed the need for urgent action to enhance support to developing countries to develop decarbonisation and long-term, low-emissions development strategies. This joint commitment illustrates the recognition of a need for consistency across development banks and DFIs, and builds on existing efforts to harmonise approaches in tracking climate finance.

In 2018, reinforcing their 2017 joint statement with IDFC, nine MDBs announced they would develop a dedicated approach to Paris alignment, identifying six “building blocks” that reflect its conceptualisation (African Development Bank et al., 2018[32]). The building blocks present Paris alignment as a process and objective that the MDBs will incorporate into internal and external activities in pursuance of the objectives of mitigation, adaptation and finance flow in Article 2.1. Three of the building blocks are clearly anchored in these objectives: align with the Paris Agreement’s mitigation goals and countries’ individual low-emissions development pathways; manage climate change risks and support adaptation; and increase and accelerate the provision of climate finance (African Development Bank et al., 2018[32]). The other three relate more to the processes that support coherent and effective implementation: i.e. support the revision of NDCs and broader policies; further develop and harmonise monitoring and reporting of Paris alignment activities; and align MDBs’ internal activities. The MDB group was to report in late 2019 on its progress on the joint approach and on advances by individual MDBs towards Paris alignment.

A 2018 IDFC position paper recognises the need to go beyond examining areas “that are directly beneficial for the climate and traditionally classified as climate finance” in aligning finance flows with the Paris Agreement (IDFC, 2018[30]). The IDFC articulated this position in the context of its joint commitment with a group of MDBs to align financial flows with the Paris Agreement (African Development Bank et al., 2018[32]). The IDFC paper focuses on Article 2.1c as a guidepost for alignment and emphasises the overarching need to mobilise finance for climate action while ensuring that the “non-climate” aspects of IDFC members’ portfolios are consistent with low-emissions, climate-resilient pathways (IDFC, 2018[30]). The paper recognises the need to increase domestic and international resources mobilised for climate action and to support country-led, climate-related policies (e.g. long-term, 2050 decarbonisation pathways). IDFC has also committed to help to enhance developing countries’ capacity for implementing climate-related policies, particularly in regard to the support for climate resilience to those most vulnerable to risks. The IDFC paper further states the IDFC’s intention to support the transition away from fossil fuels and prioritise financing for renewables, for example by embedding GHG emissions into project selection and overall decision-making processes. Finally, it notes the need for financial institutions to make the internal transformation necessary to comply with the Five Voluntary Principles for Mainstreaming Climate Action adopted at the time of the Paris Agreement in 2015 (IDFC, 2018[30]).

A number of studies in recent years have examined development co-operation providers’ progress on Paris alignment to date and reflect that Paris alignment is a far-reaching imperative that providers need to pursue across their strategies, programmes and operations. For example, a review of six MDBs’ consistency with Article 2.1c assesses progress along four extensive categories derived from the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures: governance, strategy, risk and operational management, and transformational initiatives (Wright et al., 2018[50]). Another 2018 study focuses on the role of financial policies and regulations, fiscal policy, public finance, and information instruments as part of governments’ and non-state actors’ efforts to pursue the objectives of Article 2.1c (Whitley et al., 2018[51]). Both studies are examples of the predominant focus of the Paris alignment literature to date on Article 2.1c and the critical role of finance, policy and regulation.

Development actors’ interpretations of Paris alignment suggest an emerging consensus

These examples are just a sampling of the important initiatives and approaches related to Paris alignment that are underway within the development community. Reviewed as a whole, these interpretations of Paris alignment suggest some emerging areas of consensus on its key elements among development co-operation actors and others. For example, the frameworks for identifying aligned and misaligned investments and activities – such as those devised by Larsen et al. (2018[31]) and Wright et al. (2018[50]) – indicate that certain investments and approaches are increasingly seen as fundamentally incompatible with the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

The focus so far has been on which projects and technologies to finance, often using a mitigation lens and driven by the more quantifiable and measurable elements of Article 2.1, that is, the temperature goals for climate change mitigation (Article 2.1a) and the consistency of all finance flows (Article 2.1c). As noted, this has resulted in a de facto focus on investments in hard infrastructure and assets; while clearly essential, this narrow focus relates to only a small share of infrastructure financing in developing countries (OECD, 2015[52]). Such a focus also does not appropriately account for the systemic role and constraints posed by capacity and policy gaps and their ability to unlock and direct broader financial mobilisation.

Internal and external provider policies and capacities are increasingly being integrated as key aspects for Paris alignment (Whitley et al., 2018[51]; IDFC, 2018[30]; African Development Bank et al., 2018[32]). This concept of Paris alignment needs to broaden and apply across development co-operation activities. Collectively, development co-operation actors enjoy a breadth of reach and diversity of operational models that can produce transformational impact if they embrace a broad-based approach to Paris alignment (see Chapter 3). Development co-operation should make full use of policy and capacity levers, in addition to finance, to achieve transformational change.

Incorporating climate action into overarching commitments, therefore, not only places it at the heart of sustainable development. It also enables development actors to formulate coherent strategies, programmes and operations that support sustainable development objectives and to implement climate action in accordance with the Paris Agreement. Many of the emerging approaches to Paris alignment demonstrate that development co-operation providers are embracing the Paris Agreement vision of climate action through top-down or global approaches and bottom-up, country-driven processes.

Paris-aligned development co-operation is both top-down and bottom-up