Tracing the impacts of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine on official development assistance (ODA)

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine is having direct and indirect impacts on the composition of official development assistance (ODA) and pressures that shape it. Large increases in support to Ukraine combined with spending to welcome refugees in OECD countries have driven ODA to its highest level ever. At the same time, demand for resources continues to increase elsewhere, already heightened by the COVID-19 crisis, with the war driving changes in the type and level of support needed by low- and middle-income countries. This chapter provides insights into how the development co-operation community is responding to such unprecedented demand and points to trends likely to affect ODA in 2023 and 2024.

This paper was prepared under the direction of Pilar Garrido, Director, Development Co-operation Directorate, Rahul Malhotra, Head of Division, Development Co-operation Directorate, and Ida Mc Donnell, Team Lead for the Development Co-operation Report. Editing and proofreading was by Misha Pinkhasov.

Special thanks for research assistance go to Maayan Sacher.

The authors are also grateful for contributions and feedback from: Mark Baldock, Joelle Bassoul, Elena Bernaldo de Quiros, Emily Bosch, Olivier Bouret, Olivier Cattaneo, Thea Christiansen, Stephanie Coic, Pietrangelo de Biase, Jean-Christophe Dumont, Cyprien Fabre, Philippe Herve, Jens Hesseman, Renwick Irvine, Ola Kasneci, Anita King, Fatos Koc, Ave Lauren, Rachel Morris, Amalia Pape, Santhosh Persaud, Henri-Bernard Solignac Lecomte, Andrzej Suchodolski, Sarah Spencer-Bernard, and William Tompson.

The guidance of the DAC Chair Carsten Staur is also appreciated.

1. Donor support to Ukraine is the second highest ever given to a country, after Iraq in 2005. Support to Ukraine and for refugees drove ODA to its highest-ever level in 2022, USD 204 billion. Development Assistance Committee (DAC) countries gave more than USD 16 billion in support to Ukraine and EU institutions disbursed a further USD 10 billion. This is the second-largest amount of aid ever given to a single country in a single year, behind USD 27.4 billion to Iraq in 2005, due partly to exceptional debt relief.

2. Elevated in-donor refugee costs could be here to stay. The cost of welcoming refugees in DAC countries jumped from USD 12.8 billion in 2021 to USD 29.3 billion in 2022, more than doubling as a proportion of ODA budgets. The outflow of Ukrainian refugees coincided with a sharp rise in refugees arriving in DAC countries from other countries, raising concern that DAC members will continue to spend high proportions of ODA on refugee costs, leaving less for SDGs and climate transition in developing countries, if this expenditure is not additional.

3. Reconstruction of Ukraine will require innovative approaches to financing, with a bounded role for ODA. It is estimated that reconstruction and recovery will require over USD 400 billion over 10 years, almost double the global ODA spending of DAC countries in 2022. Public and donor funding will not be enough: the Ukrainian government and its partners, particularly international financial institutions, are striving to put mechanisms in place to leverage private investment

4. Demand for ODA far outstrips supply, hence the need to ensure that every dollar achieves maximum impact. Bilateral ODA from DAC countries to least developed countries and sub-Saharan Africa dropped from 2021 to 2022, by 0.7% and 7.8% respectively. At the same time, COVID-19 and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have triggered record-high inflation, escalating public debt, food crises, and rising poverty for the first time in decades. Sudden shocks, such as the earthquake in Türkiye and Syria and the outbreak of conflict in Sudan, add to growing needs for humanitarian assistance. Combined, these crises place significant pressure on ODA budgets.

5. Rising needs for concessional development finance and humanitarian aid are highly heterogenous across developing countries, requiring tailored international development strategies. One hundred and forty-one countries are eligible to receive ODA. In 2022, their GDP growth ranged from -30% in Ukraine to 62.3% in Guyana and inflation from 1.5% in Benin to 200% in Venezuela. Pacific-Asia and North Africa were most vulnerable to the drop in Ukraine’s wheat exports. Sub-Saharan Africa struggled to compensate for the drop in fertilizer exports leading consumption to fall by 25%. Donors are challenged to respond effectively, with impact, to this rapidly evolving environment.

6. High levels of debt are a major challenge for low-income countries in 2023 and beyond. Bondholders and other private creditors now hold the highest levels of developing-country debt and China is the largest bilateral lender to developing countries, outstripping all Paris Club bilateral lenders combined. ODA lending does not feature heavily in the debt composition of most low- and middle-income countries but the demand for concessional resources will continue to grow. For countries with no market access, ODA remains a lifeline.

In 2021 and 2022, official development assistance (ODA) reached record highs, driven in large part by responses to the consecutive crises of COVID-19 and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The capacity of ODA to respond to sudden shocks has underlined its importance. At the same time, growing use of ODA for emergency response has raised concerns about the implications for development-budget composition, for example potential reduction of funds for long-term development needs.

This chapter traces the ways in which the war in Ukraine is directly and indirectly reshaping ODA supply and demand. Depressed gross domestic product (GDP) growth and high inflation in 2022 did not dampen ODA supply. Forecasts show that ODA will remain vital for recipient countries, particularly in African and least-developed countries (LDCs), where it accounts for a larger share of GDP than in other ODA-eligible countries. Despite its importance, the share of ODA focused on these contexts has declined in recent years. Against this backdrop, this chapter examines the war’s direct impacts on ODA, including increases in Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members’ support to Ukraine, driven primarily by the European Union (EU) institutions and the United States (US), and spending to welcome refugees from Ukraine during a record-high year for refugees from all countries. Elsewhere, the war and the COVID-19 crisis that preceded it have driven cost-of-living crises, a debt crunch, and poverty increases, putting additional pressure on ODA budgets and other sources of finance for targeted support that takes these rapid contextual changes into account.

In addition to reforming the international financial system (a strong demand of developing countries), raising finance for the Sustainable Development Goals, and funding longstanding and new climate commitments, development co-operation providers are facing two major challenges in 2023: 1) meet reconstruction costs for Ukraine and 2) respond to the growing levels of debt and poor access to finance among low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This chapter highlights the importance of all actors’ roles in responding to these complex needs while noting the relatively smaller and more bounded role for ODA in relation to other finance flows in meeting large development finance needs.

Building on three previous editions examining the impact of global crises on ODA (Ahmad and Carey, 2022[1]; Ahmad and Carey, 2021[2]; Ahmad et al., 2020[3]), this chapter assembles an original evidence base for DAC members and ODA-eligible countries, including key economic variables that provide the context for ODA supply and demand, and variables specifically related to support provided for the people of Ukraine (Annex A, Annex B and Annex C).

Official development assistance budgets increased in 2022 despite sluggish economic conditions in DAC countries

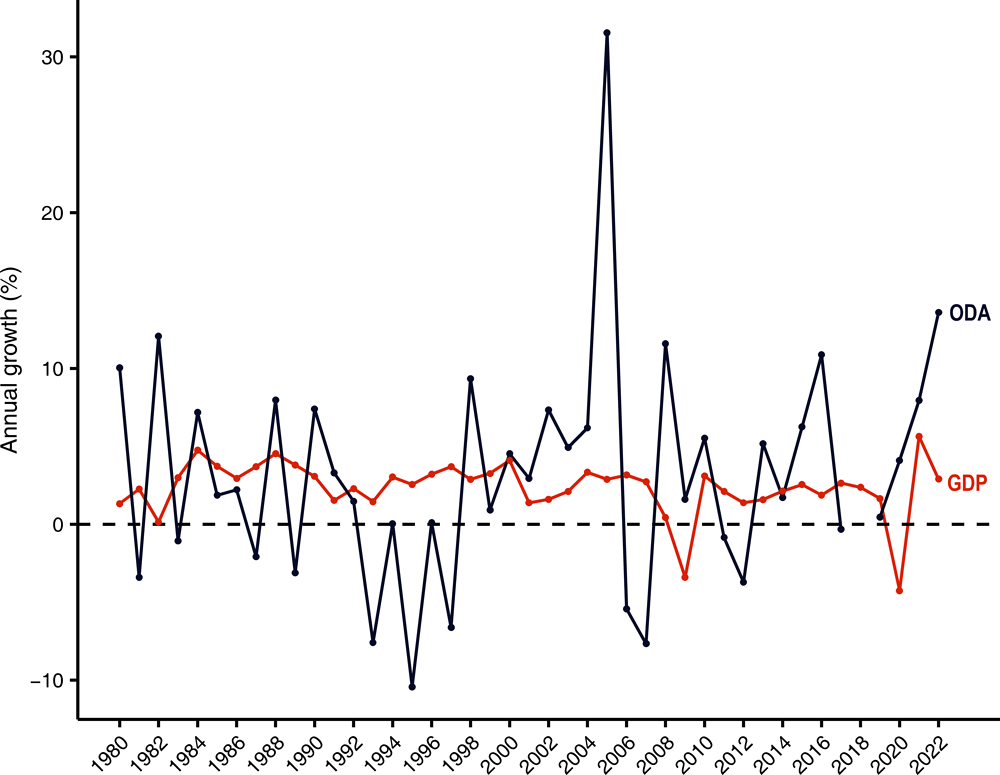

Official development assistance (ODA) by DAC member countries amounted to USD 204.0 billion in 2022, representing an increase of 13.6% in real terms over 2021. This is one of the highest growth rates recorded in ODA, at a time of global economic uncertainty and slowing-but-positive GDP growth in OECD countries (Official development assistance by OECD-DAC countries continues to increase despite economic slowdown). Additionally, ODA amounted to 0.36% of DAC countries’ collective gross national income (GNI), the highest ratio in 40 years. ODA continues to act countercyclically as previous analysis has shown (OECD, 2022[4]).

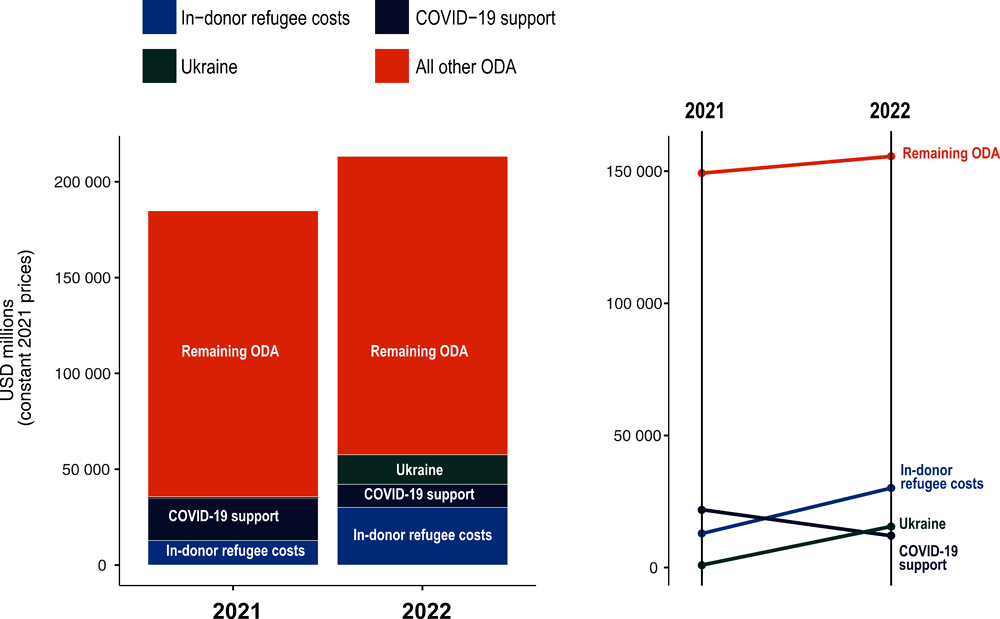

Net bilateral ODA to Ukraine (USD 16.1 billion) and ODA for processing and hosting refugees in donor countries (USD 29.3 billion) – together accounting for 22% of members’ total ODA in 2022 – helped explain this record level in ODA volume (COVID-19 support declined in 2022, but official development assistance (ODA) to Ukraine and in-donor refugee costs as well as all remaining ODA increased). Deducting in-donor refugee costs and aid to Ukraine, net ODA dropped 2% in 2022 compared to 2021, largely driven by a decline in ODA spent on COVID-19 vaccine donations to developing countries.

Deducting in-donor refugee costs and aid to Ukraine, net ODA dropped 2% in 2022 compared to 2021, driven by a decline in ODA spent on COVID-19 vaccine donations to developing countries.

Members’ ODA in response to the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and COVID-19 are examples of ODA being a “central instrument in crises” (Melonio, Rioux and Naudet, 2022, p. 12[7]), quickly and flexibly disbursed where needed. Despite this increase however, ODA spending remains below commitments such as the UN 0.7% ODA/GNI target.

ODA budgets grew from 2021 to 2022 in all but 4 of the 31 DAC members,1 despite variation in their economic backdrops: GDP growth ranged from 1% in Japan to 10.1% in Ireland, while headline inflation ranged from 2.5% in Japan to 18.8% in Lithuania (Annex A). Forecasts show that GDP growth will continue to slow in DAC countries, reaching an average of 1% in 2023 (with declines in some countries2) and 1.7% in 2024 (with all countries seeing growth). Headline inflation in DAC countries is predicted to ease to 6.5% in 2023 and 3.3% in 2024 (OECD, 2022[9]; OECD, 2023[10]), though this is above central bank targets and concern persists about underlying inflation, set to remain high in advanced economies until at least 2025 (IMF, 2023[11]). In 2022, USD 11 billion of the rise in ODA offset the increase in prices, representing 5.2 % of total ODA. In 2023, ODA would need to rise by USD 9 billion to compensate for forecast inflation in DAC countries (i.e., to have the same buying power in 2023 as 2022 ODA volumes). Particular attention might need to be paid to ODA levels in countries with contractions in GDP predicted for 2023 if this results in reductions in government spending or decreases in ODA in line with GDP.

ODA would need to rise by USD 9 billion in 2023 to compensate for forecast inflation in DAC countries.

Public expenditure and public debt in DAC countries look set to remain relatively stable in 2023 (Annex A) but debt stocks remain significantly higher than pre-pandemic levels (OECD, 2023[12]; IMF, 2023[13]). While economic factors are not the primary drivers of ODA levels (Ahmad et al., 2020[3]), this relative stability might create favourable conditions for maintaining ODA efforts at the 2022 level of 0.36% of collective GNI, following a long period of stagnation, or further increases towards the UN ODA target of 0.7%. It is worth noting that the cost of borrowing is rising and nearly half of OECD country marketable debt is due to be re-financed or re-fixed under new interest rates between 2023 and 2025 (OECD, 2023[12]), which could lead to tighter budgeting environments. However, ODA is only a small fraction of general government spending and cuts would not free up much fiscal space for providers (Carey and Desai, 2023[14]).

Official development assistance to LDCs has been decreasing but remains vital despite an outlook for strong growth

Developing countries had seen a steep decline in government revenue and foreign direct investment even before accounting for the effects of recent crises on trade and tax revenues (UNCTAD, 2022[15]; OECD, 2022[16]). Russia’s war of aggression in particular has stopped the recovery of government revenue in developing countries which is expected to remain almost 20% below pre-pandemic projections (OECD, 2022[16]). However, 2022 GDP growth in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) (4%) was stronger than in advanced economies (3.4%) and is expected to reach 3.9% in 2023 and 4.2% in 2024 (IMF, 2023[13]). While growth in low-income countries (LICs) is expected to be 5.1% on average over 2023-24, this will not be sufficient to meet their needs (IMF, 2023[13]). LICs are estimated to need an additional USD 440 billion for 2022-26 (IMF, 2022[17]). Inflation in EMDEs was higher than the world average and in advanced economies in 2022, and predicted to remain so through 2025, exacerbating financing needs (IMF, 2023[13]). Behind these averages were wide variations among ODA-eligible countries, with GDP growth ranging from -30% in Ukraine to 62.3% in Guyana (driven by the oil sector) and inflation from 1.5% in Benin to 200% in Venezuela (Annex B). The relative importance of ODA changes drastically depending on these and other factors.

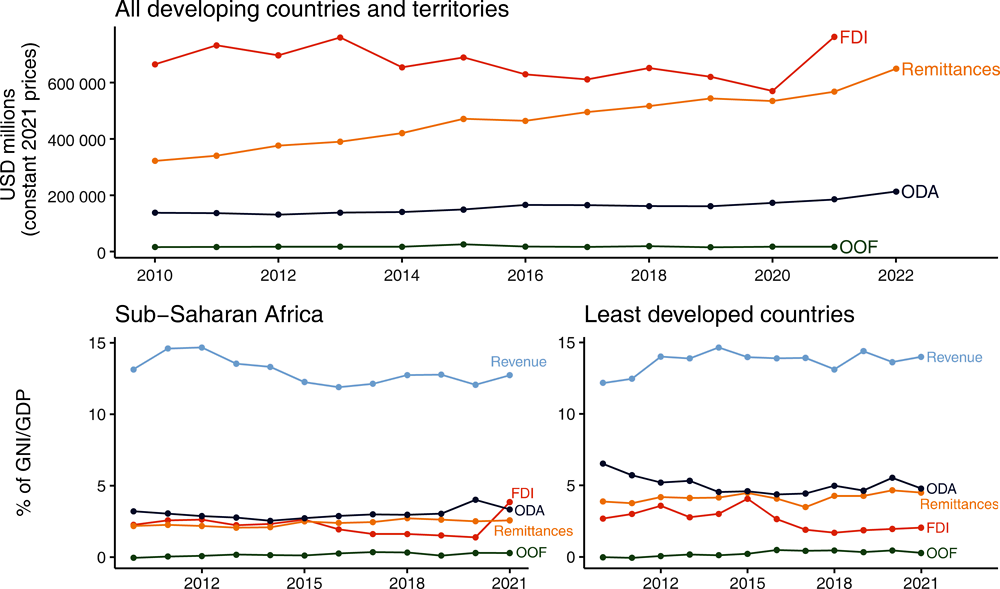

The sub-Saharan African (SSA) region, with a high concentration of LDCs, has experienced flat government revenue, and falling remittances and foreign direct investment (FDI).3 ODA remains a vital part of the financing mix, outstripping all sources as a share of GDP/GNI except government revenue in SSA and LDCs (ODA is a vital part of the financing mix for developing countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa and Least Developed Countries). Overall, bilateral DAC ODA to LDCs increased in volume by 8.5% from 2010 to 2022, even though it experienced a drop by 0.7% from 2021 to 2022. However, when taken as a share of LDCs’ GNI, net total ODA to LDCs, which also includes outflows from multilateral organisations and contributions from other official providers, has declined by 1.7 percentage points from 2010 to 2021. Additionally, ODA to SSA dropped by 7.8% from 2021 to 2022. (OECD, 2023[18]).4 Given ODA’s outsized importance to LDCs, this reversal merits attention.

ODA remains a vital part of the financing mix, outstripping all other sources except government revenue in SSA and LDCs.

Disaggregated data is key to understanding wider trends for least developed countries

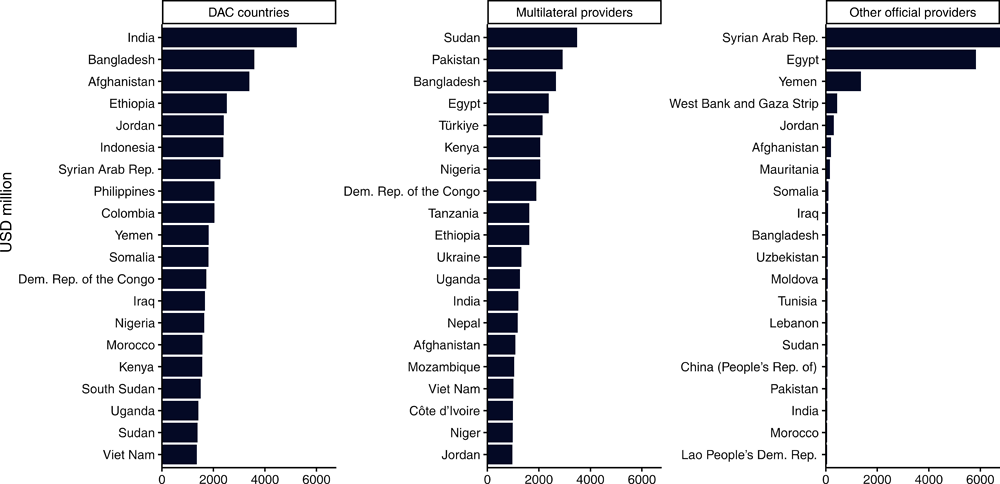

In 2021, the largest LDC recipient countries of net bilateral ODA from DAC countries were Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Yemen and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which together received 39% of total flows to LDCs. Net ODA to the top five countries grew from 2012-2021 over the last decade, except for Afghanistan where it fell by 43% in the same period. The largest donor countries were the United States, Japan, Germany, France and the United Kingdom, which together provided nearly three-quarters of DAC countries’ ODA to LDCs in 2021. Multilateral providers allocated a little over a third of their concessional outflows to Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Tanzania, combined, with the largest providers, the EU Institutions and the World Bank providing over half the aid.

It is possible that outflows from multilateral organisations in 2022 might offset the declining trend in bilateral ODA to LDCs and SSA from 2021 to 2022. While this can only be confirmed with the release of final aid statistics in December 20235, retrospective analysis suggests that an estimated average 40.4% of multilateral ODA targeted SSA from 2012 to 2021, with an upward trend over the decade, compared to an average 26.1% of bilateral ODA, which showed a declining trend. Similarly, an estimated average 36.8% of multilateral ODA targeted LDCs in the same period, compared to 27.2% of bilateral ODA. Thus, applying the average annual rate of change from 2012 to 2021 to the volume of multilateral outflows to LDCs in 2021 would increase total ODA to LDCs by 0.5%, compared to the 0.7% decline seen in bilateral ODA alone.6 However, concessionality levels are not the same: an average 55% of multilateral outflows to LDCs, and 53% to SSA, were grant-based from 2019 to 2021, compared to 87% of bilateral ODA to LDCs, and 90% to SSA. If bilateral providers strategically use the multilateral system to channel assistance to countries in need, these different concessionality levels and that should be borne in mind. Multilateral development finance overall continues to favour middle-income countries (OECD, 2022[19]).

If bilateral providers strategically use the multilateral system to channel assistance to countries in need, different concessionality levels should be borne in mind.

In addition to support from DAC members, outlined above, low- and middle-income countries receive financing from a range of partners, which provide different types and levels of support depending on financing needs, geographical and thematic priorities, pre-existing partnerships, and the capacities of countries to manage certain types of financing. In 2021, DAC countries allocated the highest combined amounts to India, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, while multilateral providers made the largest outlays to Sudan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Other official providers7 concentrated their support on the Syrian Arab Republic and Egypt8 (A range of official providers give ODA to developing countries). Total ODA from DAC countries accounted for 90.7% of all ODA received by developing countries in 2021 from all providers that reported to the OECD.

ODA budgets have responded to Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine in two ways: the large disbursement of concessional finance to Ukraine and significant spending to welcome the people fleeing the war in DAC countries.

How much have DAC members committed and spent in Ukraine?

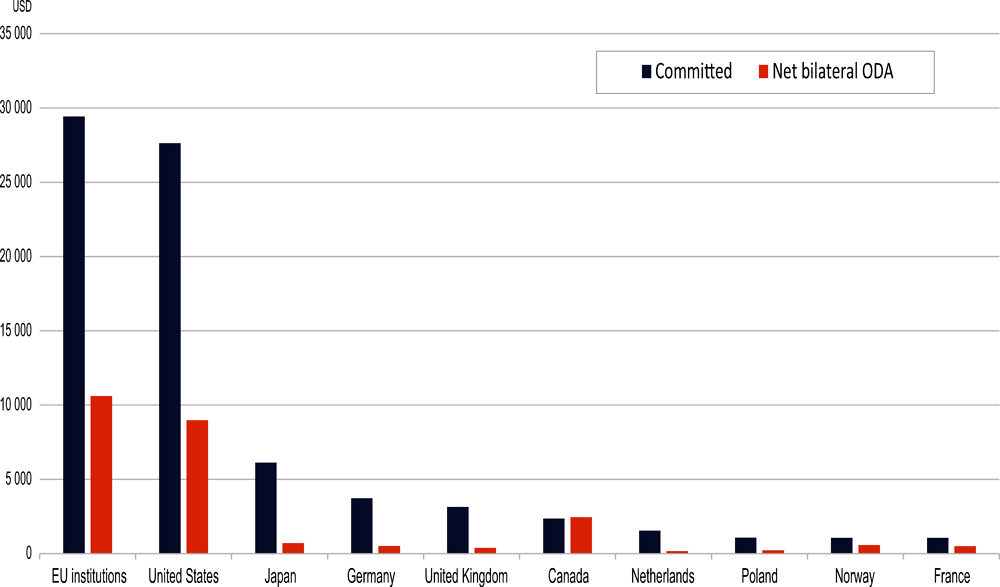

Bilateral spending by DAC countries in Ukraine was USD 16.1 billion in 2022. This volume represents the second-largest amount of aid given to a single country in a single year, behind USD 27.4 billion to Iraq in 2005, half of which was debt relief. For comparison, the volume of ODA in 2022 to Ukraine is greater than bilateral ODA in 2021 to the top five recipients combined,9 and more than double what Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen together have received in any year.10 EU institutions gave a further USD 10.6 billion, amounting to 38.4% of their total ODA. By comparison, Egypt was the largest recipient country of EU institutions’ bilateral ODA in 2021, receiving USD 2.1 billion. DAC members together therefore mobilised USD 26.7 billion in ODA for Ukraine in 2022.

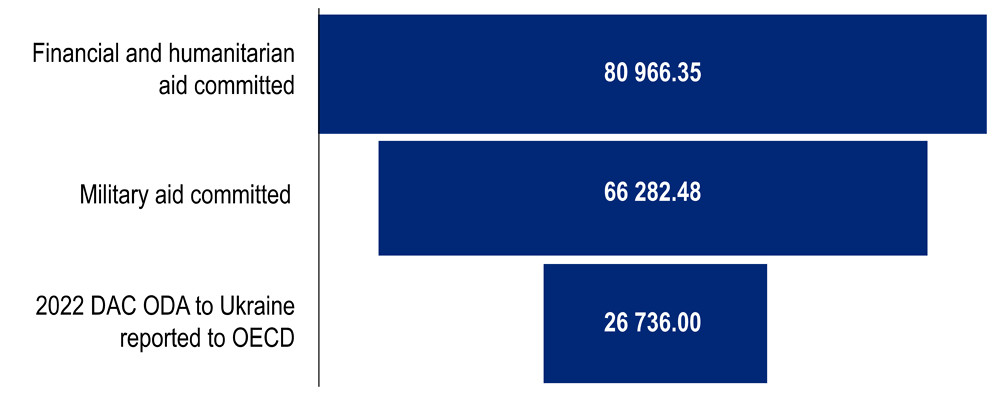

DAC members’ humanitarian and financial commitments to Ukraine, as tracked by the Kiel Institute up to 24 February 202311 amounted to nearly USD 81 billion (Kiel Institute, 2023[20]) (DAC members’ ODA to Ukraine in 2022 equalled one-third of financial and humanitarian commitments to Ukraine). The large difference between commitments and ODA reported is likely explained by factors including but not limited to: commitments not equalling disbursements; commitments made in 2022 being disbursed over multiple years; not all financial and humanitarian support meeting criteria to qualify as ODA though Ukraine is an ODA-eligible country; 2022 ODA data being preliminary and reporters still gathering information about total support to Ukraine that year. Preliminary 2022 ODA figures for support to Ukraine are therefore equivalent to about one-third the amount of financial and humanitarian support committed since the beginning of the war.

Preliminary 2022 ODA figures for support to Ukraine are therefore equivalent to about one-third the amount of financial and humanitarian support committed since the beginning of the war.

ODA disbursed to Ukraine in 2022 is equivalent to about 40% of military assistance committed by DAC members (USD 66 billion), which does not qualify as ODA, and to a small fraction of military expenditure by states in Central and Western Europe in 2022, which was partly driven by countries’ reaction to Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine (SIPRI, 2023[21]). Thus, ODA is a relatively small part of this larger budget effort.

Trends in support to Ukraine are largely driven by two donors: EU institutions (see DCR Profile of EU institutions (OECD, 2022[22])) and the US (see DCR Profile of United States (OECD, 2022[23])). The largest commitments tracked by the Kiel Institute are USD 30 billion from EU institutions and USD 28 billion from the US, of which the majority is financial support. This is mirrored in the preliminary ODA data on bilateral net disbursements, with the EU (USD 10.6 billion) and US (USD 8.9 billion) being the largest donors to Ukraine in 2022 (Of all DAC members, EU institutions and the US made the largest commitments and ODA disbursements to Ukraine).

Trends in support to Ukraine are largely driven by two donors: the European Union and the United States.

Loans are a key feature of support to Ukraine, particularly from the EU

According to the Kiel Institute tracker, nearly USD 42 billion, or just over half of total financial aid committed, was in the form of loans. EU institutions committed USD 29.7 billion, with the largest single commitment (EUR 18 billion) to support macroeconomic stability, public services and wages, and fund reconstruction of critical infrastructure. The EU had been supporting Ukraine with loans before the war, with a large increase in lending for general budget support and infrastructure investments in 2020 (OECD, 2022[4]). Other significant loan commitments up to February 2023 were made by Japan (USD 6.1 billion), Canada (USD 1.8 billion), and France (USD 0.7 billion). G7 and Paris Club members announced a suspension of Ukraine’s debt service payments from 1 August 2022 until end of 2023, with the possibility of extension for an additional year (European Parliament, 2023[24]). Lending is not an unusual financing mechanism for middle-income countries like Ukraine. This group received 43% of ODA lending in 2021, the value representing 18% of gross bilateral ODA that year.

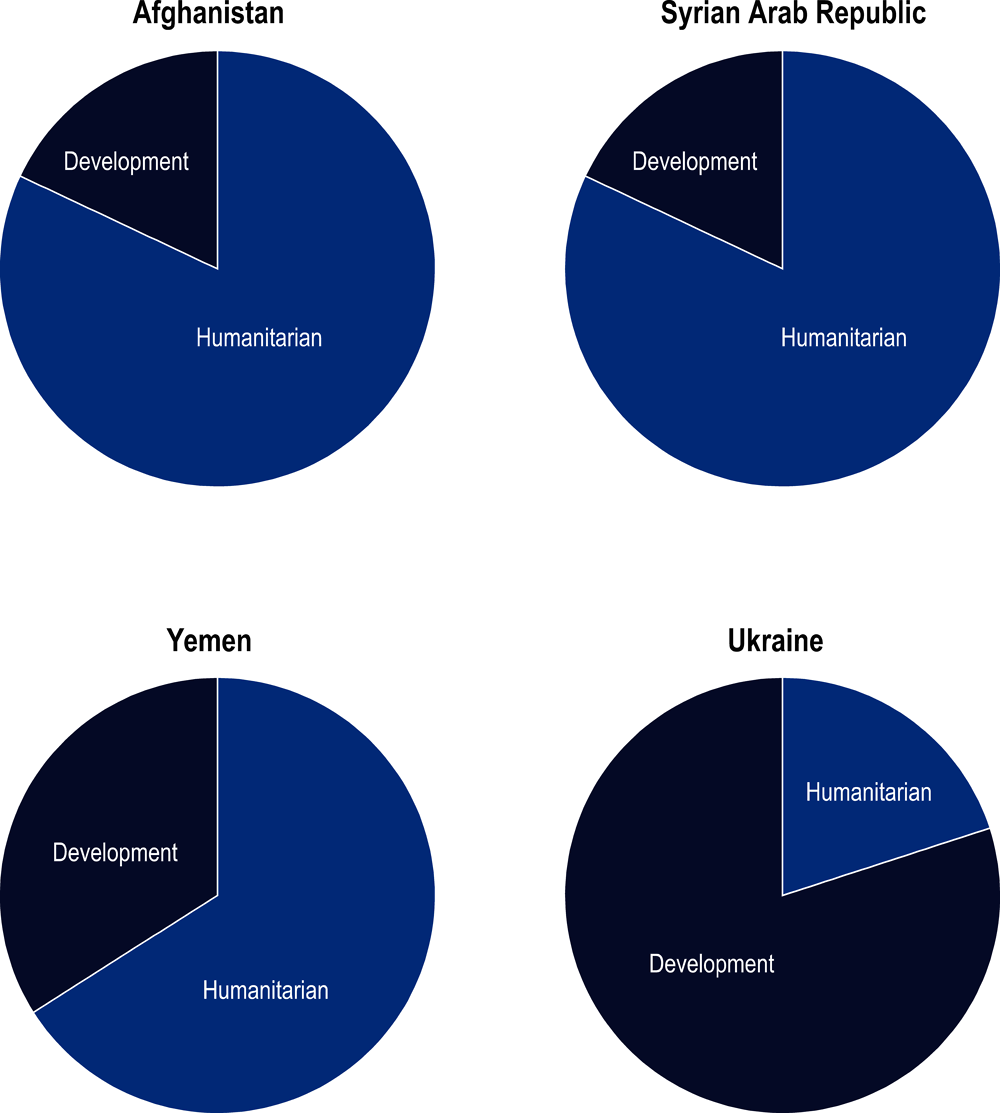

The share of humanitarian aid in financing for Ukraine is smaller than for other major conflicts

The split between financial (development-oriented) and humanitarian support to Ukraine differs markedly from that in other conflicts. Estimates of financial commitments to Ukraine suggest that humanitarian pledges account for one-fifth of total financial assistance (Kiel Institute, 2023[20]).12 In contrast, in the first year of violent conflict in Afghanistan (2001), 82% of bilateral ODA disbursements were humanitarian. Similarly, in the first years of violent conflict in Syria (2012) and Yemen (2015), humanitarian aid was 82% and 66% of total ODA, respectively (Humanitarian and development-related assistance in Ukraine so far: an atypical split). Notably, in the latter two cases, more than 70% of ODA was humanitarian from after the first year of conflict up to 2021: the crisis response model followed by DAC donors remains overly reliant on humanitarian support over the long term (OECD, 2022[25]). Additionally, both Syria and Yemen were middle-income before their respective conflicts, having since been reclassified as low-income economies (World Bank, 2023[26]).

Why is support to Ukraine more development-oriented than humanitarian-focused? First, the government of Ukraine remains in situ and continues to provide and co-ordinate public services, limiting the role for humanitarian actors to fill public service gaps. Second, pre-existing infrastructure and a partially functioning economy mean humanitarian needs are not as large as in other conflict situations—albeit noting the severity of humanitarian needs for internally displaced populations and in parts of the country under the military control of Russia (OCHA, 2022[27]). Third, the geographic proximity of this war to OECD members, particularly in Europe, has led to larger budget provisions to welcome refugees than was the case during other conflicts, which could account for some variations in spending behaviour. Finally, this spending pattern may also be an indication of strategic political support to the Ukrainian government.

The nature of the response has implications for Ukraine’s post-war reconstruction and recovery efforts, (see below: “Trends to watch in 2023 and beyond”) and donor responses to other conflicts, especially as they seek coherence and complementarity in their efforts across the humanitarian, development, and peace nexus (OECD DAC, 2019[28]). For example, this composition of assistance to Ukraine underscores the fact that humanitarian aid, while important in addressing immediate needs at the onset of conflict, are not the only mechanisms that donors can use in conflict situations; development and peace-related assistance can also play important roles depending on the context (OECD, 2022[25]). It is important for donors to consider the entire range of mechanisms and tools available to ensure that the right financing reaches the right countries at the right time (OECD, 2018[29]).

How have DAC members responded to escalating in-donor refugee costs?

By April 2023, over 8 million refugees from Ukraine had been recorded across Europe with just over 5 million having registered for Temporary Protection or similar national schemes since the start of Russia’s invasion against Ukraine (UNHCR, 2023[30]). The increase in Ukrainian refugees came at a time of growing pressure on asylum systems, as factors such as climate-change, conflict, and the lifting of COVID-19-related travel bans led to increased numbers of people seeking protection. In the first six months of 2022 alone, DAC countries collectively received asylum applications from all regions equivalent to 72% of all applications received in 2021, with some receiving twice the number of applications during that period as in the whole of the previous year (Annex B). European Union countries saw a 64% increase in first-time asylum seekers from 2021 to 2022 (Eurostat, 2023[31]). The top nationalities applying for protection were Syria, Afghanistan, and Türkiye (EUAA, 2023[32]). In 2021 the United States put in place a target to scale up a refugee programme (known as USRAP) to 125,000 admissions annually, leading to an increase in admissions overall in 2022 and the resettlement of 80,000 Afghans (U.S. Department of State, 2023[33]).

The increase In Ukrainian refugees came at a time of growing pressure on asylum systems, as factors such as climate-change, conflict, and the lifting of COVID-19-related travel bans led to increased numbers of people seeking protection.

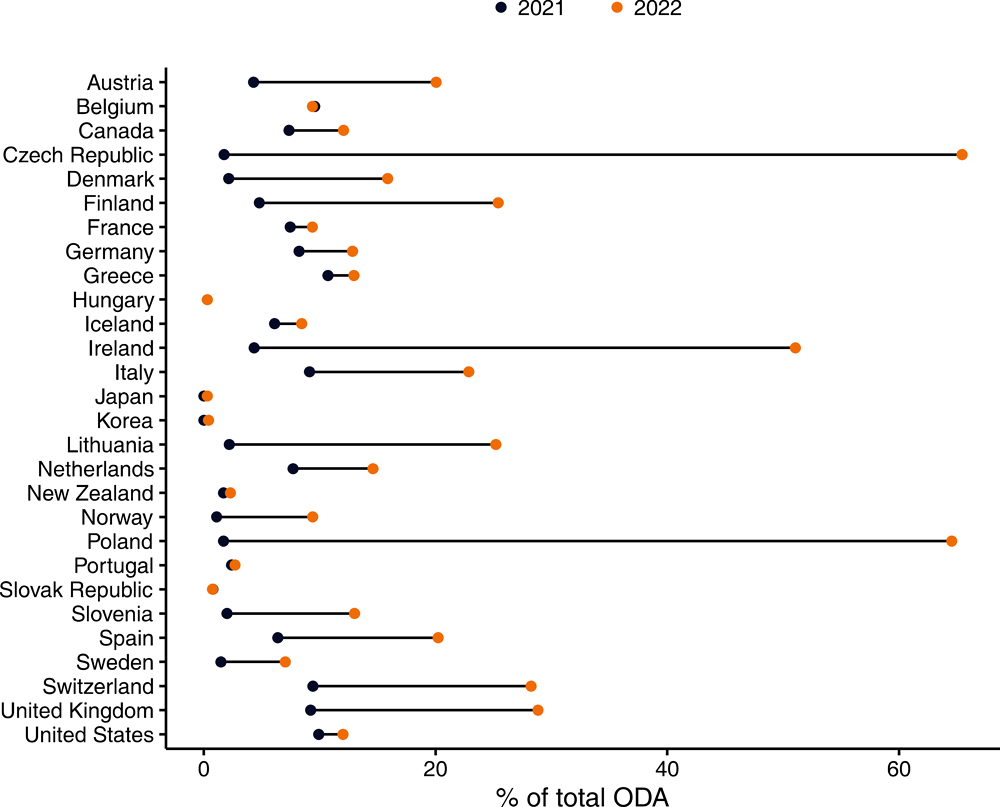

In-donor refugee costs (IDRCs) funded from ODA budgets rose from USD 12.8 billion in 2021 (6.9% of total ODA from DAC countries that year) to USD 29.3 billion in 2022 (14.4% of total ODA).13 IDRCs as a portion of ODA budgets rose for most members but not uniformly (In-donor refugee costs have had varied impacts on ODA budgets). The increase in ODA from 2021 to 2022 was sufficient to absorb the elevated cost of IDRCs in 17 DAC countries, but this was not the case in others (Annex B).

Some DAC countries were destinations for large numbers of Ukrainian refugees in 2022, others received high numbers of asylum applications, and some experienced both (Elevated numbers of refugees fleeing the war in Ukraine coincided with higher numbers of asylum seekers in many countries in 2022). Poland (see DCR profile of Poland (OECD, 2022[34])) and the Czech Republic (see DCR profile of Czech Republic (OECD, 2022[35])), the countries with the largest portions of ODA budgets going to IDRCs in 2022, were among the top three countries receiving Ukrainian refugees. Ireland (see DCR profile of Ireland (OECD, 2022[36])) had the third highest portion of ODA for IDRCs in 2022. In Poland and Ireland additional resources reported as ODA were sufficient to cover the elevated IDRCs in 2022 (Annex B).

IDRCs are driven by costs in host countries, mechanisms for support, and the number of refugees arriving. Not all refugees require the same level of protection and support. The triggering of the Temporary Protection Scheme for Ukrainian nationals in the EU means that they have the right to work in many countries and early indications are that their participation in labour markets has been faster than that of other refugee groups (OECD, 2023[37]). EU member states receive some compensation from the European Commission to help with the cost of welcoming Ukrainians. In some countries, support is given through the wider social-protection system rather than special refugee-support schemes. This could lead to costs for Ukrainian refugees differing from costs for other refugees. The OECD is currently surveying members for more granular information on costs.

While some DAC countries attempt to cushion the impact of increasing IDRCs on their ODA budgets (DAC country mechanisms to respond to increasing costs of welcoming refugees), the rise in costs, the portion of ODA allocated to IDRCs, and the practice of reporting IDRCs as a component of ODA raises concern (DAC-CSO Reference Group, 2023[38]; ICAI, 2023[39]; Netherlands Court of Audit, 2023[40]). For example, civil society organisations noted that “Countries can and should support the reception of refugees and asylum seekers, but the budgetary costs should be covered through alternative financing and budget sources to the ones already allocated to ODA” (DAC-CSO Reference Group, 2023[38]).

DAC rules underline that: (1) refugee protection is a legal obligation; (2) it is considered a form of humanitarian assistance; (3) DAC countries can count the cost of welcoming refugees in their ODA within certain limitations; and (4) methodology applied to count these costs should be conservative. DAC country practice varies, with some using mechanisms to cushion or mitigate the impact on ODA budgets. Mechanisms put in place during the last large increase in migration to the EU (2015-16) and in 2022 demonstrate the variety of approaches.

2015-16

In response to the 2015-16 increase in migration to the EU, Sweden implemented an IDRC cap at 30% of its ODA budget. Other members set up more flexibility in multi-year budget appropriations to smooth the impact on their ODA budgets over a longer period. Iceland implemented improvements in accounting for IDRCs.

2022

17 DAC members increased the volume of their ODA sufficiently to compensate for the increase in IDRCs.

Belgium opted to exclude exceptional ad-hoc IDRCs under the European Temporary Protection Directive that was reactivated following the invasion of Ukraine.

The Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs agreed with its Ministry of Finance that no more than EUR 150 million of the cost to welcome Ukrainian refugees would come from the ODA budget.

Poland established an aid fund to support public-finance intermediaries in the distribution of aid to refugees from Ukraine who found shelter in Poland. The fund pools state budget finances with EU funds, bonds issued by Poland’s national development bank, and donations.

The Slovak Republic opted to include only eligible in-donor costs related to statutory asylum-seekers.

Note: Mechanisms listed here are not exhaustive but indicative of approaches. Other countries not listed here may have taken steps to mitigate the impact of IDRCs on ODA.

Source: Ahmad and Carey (Ahmad and Carey, 2022[1]) (2022[1]) "How COVID-19 and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine are reshaping official development assistance (ODA)", in Development Co-operation Profiles, https://doi.org/10.1787/223ac1dd-en; , KMPG (2021[41]) , “Evaluation of in-donor costs for asylum seekers and quota refugees in Iceland”, www.government.is/library/01-Ministries/Ministry-for-Foreign-Affairs/Int.-Dev.-Coop/Evaluations/Evaluation%20of%20in-donor%20costs%20English%20version.pdf; Government of the Netherlands (n.d.[42]) “Dutch aid for Ukraine: from day to day”, www.government.nl/topics/russia-and-ukraine/dutch-aid-for-ukraine; https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/ODA-2022-summary.pdf ; https://www.en.bgk.pl/funds/aid-fund/; https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/sweden_2023_mid_term_review_letter.pdf

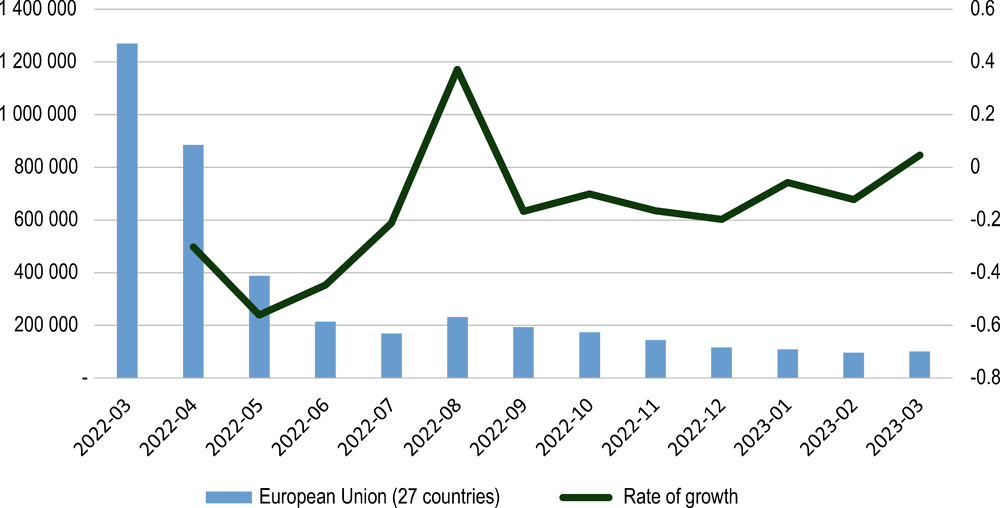

The number of Ukrainians fleeing the war has plateaued in Europe since mid-2022 (The number of Ukrainian refugees applying for temporary protection in Europe has levelled off, with little growth since mid-2022). These data do not take into account Ukrainians who may have registered for temporary protection in an EU country and later returned to Ukraine or moved to other countries (for example there has been some increase in secondary flows in non-EU countries such as Canada, the US, and the UK); therefore actual numbers might be lower. Without another large outflow of Ukrainians, the proportion of IDRCs incurred to provide support to this group should fall in 2023 owing to the twelve-month rule, which states that expenditure by DAC members on eligible refugees and agreed cost items cannot be counted in ODA flows beyond 12 months (OECD, 2023[43]). However, the overall magnitude of IDRCs in 2023 and beyond could depend less on the number of Ukrainian refugees than on individuals arriving in DAC countries from other countries.

The overall magnitude of IDRCs in 2023 and beyond could depend less on the number of Ukrainian refugees than on individuals arriving in DAC countries from other countries.

Disaggregated final data for 2022 that will become available at the end of 2023 will allow additional analysis including:

Total number of refugees and asylum applicants received by countries in 2022

Refugees’ country of origin, allowing for distinction of costs for Ukrainian refugees versus refugees from other countries

The level of support DAC members provided to refugees hosted in other DAC countries

Any consequences of increased support to Ukraine or ODA to host refugees in donor countries for ODA spending on other priorities or countries

Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has created devastating ripple effects around the world. Developing countries were already struggling to recover from the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis before war compounded already unprecedented levels of need. ODA providers made significant budget efforts, disbursing a combined USD 47 billion dollars over 2020 to 2022 for COVID-19 response (discussed in more detail below). However, Russia’s war in Ukraine is changing the scale, intensity and type of needs in low- and middle-income countries. Coupled with rising demand for humanitarian resources spurred by disasters and other conflicts, ODA budgets are under severe strain and trade-offs for the world’s poorest people are becoming evident.

The scale, intensity, and type of needs are changing across developing regions, calling for more targeted responses by providers of development co-operation

In the world’s most vulnerable countries people’s struggle to meet basic needs was already severe in the wake of COVID-19 and has been made even more difficult by the impacts of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine (UNDP, 2022[44]; World Bank, 2023[45]). This evolution underscores the changing scale, intensity, and type of needs worldwide.14

Tightness in the energy market following re-opening after the COVID-19 crisis has been exacerbated by Russia’s war in Ukraine leading to energy prices reaching historic highs. Countries unable to pay these higher prices struggle to compete and secure energy supply. In Africa in particular, higher market prices are reversing trends in improving access to energy (IEA, 2022[46]).

Noting that food prices were already rising prior to the invasion (FAO, 2022[47]), the war in Ukraine aggravated food shortages, with significant declines in the Ukrainian production and export of wheat and other commodities impacting developing regions, in particular Pacific-Asia and North Africa, which received an average 30% and 27% of Ukraine’s wheat exports, respectively, over 2016-2020 (European Council, 2023[48]). These food shortages disproportionately affect poorer countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which receives 87% of its wheat imports from Russia (FSIN and Global Network on Food Crises, 2023[49]). Global fertiliser trade, a key to boosting food security, was also impacted. Sanctions on major suppliers Russia and Belarus, and export restrictions to conserve supply for domestic use, particularly in China, led to significant shortfalls (IFPRI, 2023[50]). While some countries switched to other suppliers, estimates for sub-Saharan African show fertilizer consumption down 25% in 2022 (IFPRI, 2023[50]). The Black Sea Grain Deal, which kept Russian and Ukrainian exports of grain and fertilizer from collapsing in 2022, remains short-term and subject to all parties’ continued co-operation (VOA, 2023[51]). Between 2015 and 2021, the total official flows to agriculture in developing countries increased by 14.6 per cent, from USD 12.8 billion to USD 14.2 billion (in constant 2021 prices). Total aid to agriculture peaked in 2020, when it grew by nearly 18 per cent compared to 2019, partly due to food security concerns during the pandemic. However, in 2021, it fell by 15 per cent and in terms of volume, was close to its pre-pandemic levels.

Development co-operation providers will need to consider the varied needs of different regions (Needs are highly variable across regions and being transformed by crises) and the ways in which recent crises have exacerbated these to tailor and target support. In sub-Saharan Africa, more than a third of the population is in extreme poverty15 in 2023, with the extreme poverty rate expected to be 28% by 2030 based on projected economic growth. With almost half (43%) of countries in the region being in or at a high risk of debt distress, and government revenue amounting to 18% of GDP – compared to general government debt of 38.7% of GDP – amid historic levels of inflation, sub-Saharan Africa faces a “big funding squeeze” (IMF, 2023, p. 3[52]). This is affecting governments’ ability to fund sectors critical for addressing extreme poverty, such as health, education, and social protection The recent experience of Nigeria, which has the highest rate of extreme poverty in Africa, illustrates these funding gaps and trade-offs: in 2022, the Government spent the equivalent of 96.3% of its revenue on debt servicing (World Bank, 2023[53]).

Meanwhile, ODA to sub-Saharan Africa accounts for an average 21.4% of DAC countries’ bilateral ODA from 2020 to 2022. By comparison, ODA to Asia amounts to 23.2% of the total in the same period, despite countries in Asia facing lower intensity of need on average across several indicators (Needs are highly variable across regions and being transformed by crises). As circumstances evolve and ODA funds remain under pressure, it is important for DAC countries to keep this spectrum of needs in mind to ensure that every dollar can work harder to help partner countries achieve sustainable development and peace (OECD, 2023[54]).

ODA-eligible countries geographically close to Ukraine are also likely to need increased support. Reduced remittances from Russia and rising inflation have raised concerns about rising poverty in Caucasus countries (IMF, 2022[55]). Developing countries in Europe have seen the highest annual increases in inflation rates in 2022 (Needs are highly variable across regions and being transformed by crises). Fifteen of 40 downgrades in credit ratings seen in emerging markets and developing economies in 2022 were in European countries reflecting the effect of the war (OECD, 2023[12]). This decline in the credit quality of EMDEs and rise in borrowing costs occurs against a backdrop of high refinancing needs from bonds in the upcoming three years.

DAC members have made significant budget efforts to respond to the COVID-19 crisis, driving increases across countries and sectors

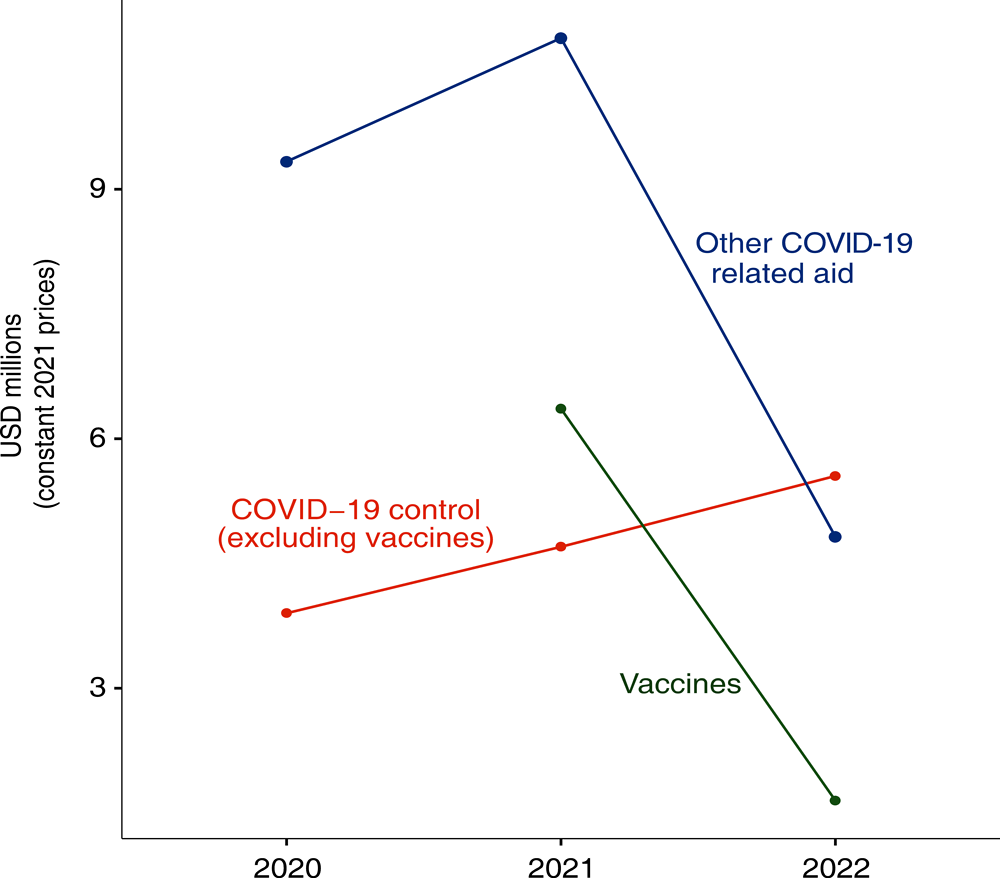

DAC members provided USD 47 billion (constant 2021 prices) from 2020 to 2022 to support developing countries’ responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (USD 13.2 billion in 2020, USD 21.9 billion in 2021, and USD 12.0 billion in 2022).16 The 45% decline in real terms from 2021 to 2022 was led by decreased spending on vaccines (from USD 6.4 billion in 2021 to USD 1.53 billion in 2022), reflecting a drop in the volume of donations made, (the OECD recommended that an average price of USD 6.66 per vaccine dose should be used in 2022 ODA and USD 6.72 in 2021 as determined by GAVI and aligned with the COVAX Facility), while support for COVID-19 control increased (Spending on COVID-19 vaccines declined in 2022, but support to COVID-19 control increased).

The 45% decline in COVID-19-related ODA spending from 2021 to 2022 was led by decreased spending on vaccines, while support for COVID-19 control increased.

COVID response funding was also provided in the form of sector budget support. In addition, DAC members provided bilateral support to the Gavi COVAX Advance Market Commitment for the development and procurement of vaccines to benefit developing countries, as well as the ACT-Accelerator and the CEPI.

DAC members’ focus on COVID-19-related spending has shifted from vaccines to control

COVID-19 control includes activities focussed on testing, prevention, vaccines and immunisation, treatment and care, and information, education and communication. DAC member countries spent USD 3.7 billion on COVID-19 control in 2020 which represented 23% of total ODA for COVID-19. This rose to USD 11.1 billion in 2021, representing 51% of total ODA for COVID-19. In 2022, spending on COVID-19 control stood at USD 7.0 billion. The sharp increase in 2021 was driven by vaccine donations, which represented USD 6.4 billion. Excluding vaccine donations, the share of COVID-19 control in overall COVID-19-related aid remained stable at around 21%. For multilateral organisations, the share of COVID-19-control spending within total COVID-19 activities rose from 0.5% in 2020 to 15% in 2021. This dynamic changed in 2022, when support to vaccines declined and support to other components increased.

Excluding vaccine donations, ODA in 2021 for COVID-19 control amounted to USD 4.7 billion. Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the US were the top five DAC-country donors, representing over two-thirds of total DAC aid provided for COVID-19 control other than vaccines.

Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the US were the top five DAC-country donors, representing over two-thirds of total DAC aid provided for COVID-19 control other than vaccines.

The bulk (89%) of aid for COVID-19 control, excluding vaccines, from DAC countries was provided in the form of grants, with France, Italy, and Korea providing some support in the form of ODA loans. EU institutions provided approximately one-third of their aid for COVID-19 control in the form of loans.

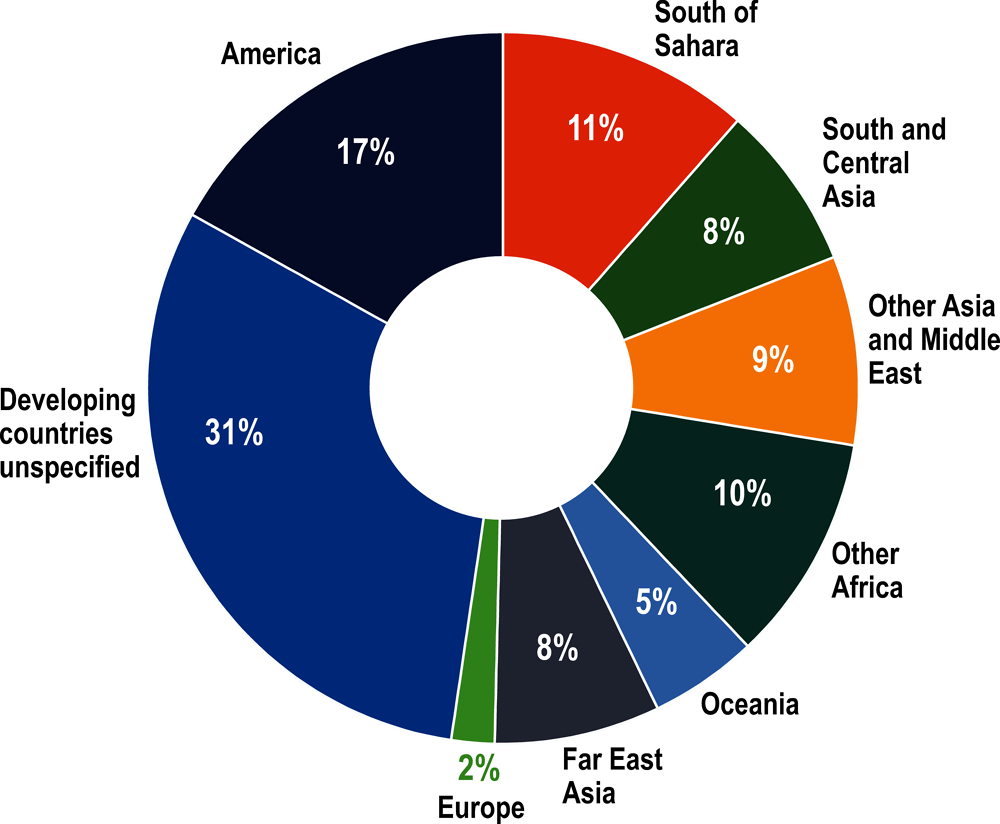

In terms of regional allocations, about one-third of aid for COVID-19 control, excluding vaccines, from DAC member countries was unallocated by region. Asia (USD 1.1 billion) and Africa (USD 1 billion) were the largest recipient regions (DAC countries’ support to COVID-19 control by region).

In 2021, nearly half of support for COVID-19 control was delivered through UNICEF (USD 777 million), Gavi (USD 740 million), and WHO (USD 609 million), while 15% (USD 732 million) was channelled through recipient-country governments.

Increased COVID-19 spending was mostly driven by grants, with some countries receiving large portions of their ODA as COVID-19 related aid

Multilateral COVID-19-related spending grew from USD 8.7 billion in 2020 to USD 15.2 billion in 2021, while COVID-19-related support by non-DAC providers remained constant at USD 0.5 billion in 2020 and 2021. But this increased role of multilaterals did not push the composition of COVID-19-related support towards higher levels of loans, as might have been anticipated. On average, about two-thirds of COVID-19-related aid by all donors in 2020 was provided in the form of grants, and one-third as loans or other types of non-grant finance, whereas in 2021, the share of grants rose to three quarters and the share of non-grant finance dropped to one quarter.

The increased role of multilaterals has not pushed the composition of COVID-19-related support towards higher levels of loans.

COVID-19-related aid has accounted for a large share of some recipient countries’ total ODA received over the period (Top recipients of COVID-19-related aid (2020-21 average)).

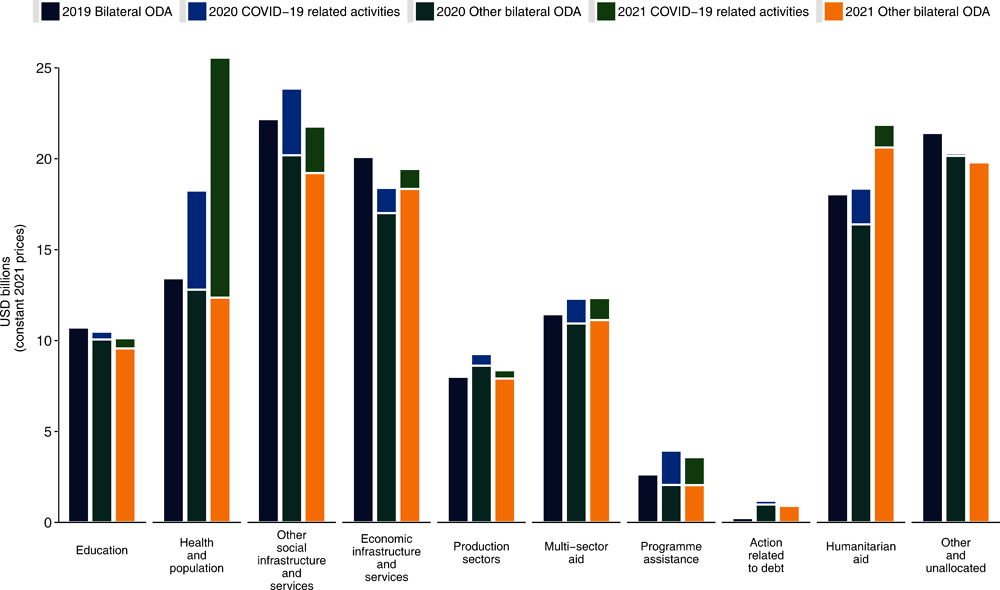

COVID-19 related spending benefitted all sectors, particularly health, with no evidence of offsetting

Given that 2020 budgets were set before the pandemic, there was little evidence of significant aid re-allocations between sectors that year, with gross bilateral ODA to all sectors increasing due to additional COVID-19 allocations. This trend was confirmed in 2021 figures, which showed no significant changes in ODA allocations across sectors compared to 2020 (DAC countries’ bilateral ODA showed no significant changes in allocations by sector during 2020-21). Of the USD 21.9 billion DAC countries spent on COVID-19 in 2021, USD 13.2 billion was for health and population activities, an increase of 142% over 2020, and included USD 6.4 billion of COVID-19 vaccine donations. Excluding vaccines, ODA for the health and population sector increased 25%. This increase in funding to support health systems in developing countries will require a further commitment by donors to ensure that populations have access to health services, which were overwhelmed during the pandemic, and not reverse health outcomes that have already been achieved. COVID-19-related aid for education rose 31% in 2021, while most other sectors saw a drop in COVID-19-related spending, with economic infrastructure falling 21%, the production sector 28%, and humanitarian aid 37%.

2021 figures showed no significant changes in ODA allocations across sectors compared to 2020.

ODA for social protection which had risen 162% in 2020, fell 12% in 2021, and general budget support which had increased 91% in 2020 fell 27% in 2021.

COVID-19 spending had a positive effect on all country income groups in 2020, but this effect began to wane in 2021

Growth in 2020 in bilateral ODA from DAC member countries across all country-income groups was driven by COVID-19-related aid. However, in 2021, ODA fell across all groups except for LMICs, where it grew 2%. Excluding COVID-19-related aid, ODA rose 4% in LDCs but remained below its pre-pandemic levels in 2019. Similarly, flows from multilateral organisations increased in 2020 due to COVID-19-related expenditures (ODA by income group including and excluding COVID-19 related aid (2019-21)). In 2021, multilateral ODA to LDCs and LMICs increased 3% and 4% respectively; in contrast, excluding COVID-19-related aid, multilateral ODA to LDCs fell 22% and remained below its 2019 level.

In comparison to (pre-pandemic) 2019, the dynamics outlined above indicate that COVID-19 spending had a significant, positive effect on ODA receipts among all country-income groups and that increased spending on health and other relevant sectors was not offset by reductions elsewhere, at least during 2020 and 2021. In May 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that COVID-19 was no longer a public health emergency of international concern (WHO, 2023[56]) and called for a shift to long-term disease management (WHO, 2023[57]). That COVID-19-related spending seems to have shifted away from vaccines and towards control might indicate that ODA has already begun to shift in line with the WHO’s call. However, if the end of the pandemic precipitates a fall in COVID-19-related ODA spending, this might have a disproportionate impact on countries where such spending is a large component of ODA receipts. ODA providers will need to consider ways to maintain focus on health systems and managing any decreases carefully with partners.

If the end of the pandemic precipitates a fall in COVID-19-related ODA spending, this might have a disproportionate impact on countries where such spending is a large component of ODA receipts.

Disasters and other conflicts continue driving demand for humanitarian resources, with trade-offs for development

2021 and 2022 saw record-high appeals for humanitarian assistance, followed by a 25% increase in the estimated cost of humanitarian response in 2023, amounting to USD 54.6 billion (UNOCHA, 2022[58]) – a 169% increase from 2016. The number of people experiencing acute food insecurity rose from 193 million in 2021 to 258 million in 2022, largely as a result of economic shocks and the impact of the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine (WFP, 2023[59]). In 2022, 57% of requirements were funded (UNOCHA, 2023[60]).

Sudden shocks, such as the earthquake in Türkiye and Syria and the outbreak of conflict in Sudan, add to growing needs for humanitarian assistance. As of May 2023, 30.2% of requirements for the flash appeal for Türkiye were met (UNOCHA, 2023[61]) and 98.9% for Syria (UNOCHA, 2023[62]), with the United States and Germany being the biggest contributors to both. As of 9 May 2023, 700,000 people were estimated to be internally displaced by the fighting in Sudan, alongside more than 150,000 refugees, asylum seekers, and returnees (UNHCR, 2023[63]; UN, 2023[64]). Meanwhile, requirements for the 2023 response plan for Sudan were 14% funded by early May 2023 (UNOCHA, 2023[65]).

Sudden shocks, such as the earthquake in Türkiye and Syria and the outbreak of conflict in Sudan, add to growing needs for humanitarian assistance.

Humanitarian and food aid as a portion of bilateral ODA has risen in response to the increasing scale, frequency and duration of crises over the past decade, from an average of 10% in 2010-12 to 15.2% in 2019-21 (OECD, 2023[54]). In fragile contexts, where needs are concentrated (OECD, 2022[25]), humanitarian aid amounted to 28% of DAC countries’ bilateral ODA in 2021 – a historic high. By comparison, ODA for peacebuilding and conflict prevention totalled 10% of bilateral ODA – a historic low. Thus, in 2021, for every dollar spent on peace-related ODA to address the root causes of crises, member countries spent almost three dollars on humanitarian assistance to respond to crises, reflecting a tendency toward ‘firefighting’ rather than prevention (OECD, 2018[29]).

Disaggregated final data for 2022 that will become available at the end of 2023 will allow additional analysis including:

Breakdown of spending by DAC members by individual recipient countries and regions, allowing for analysis of any geographical re-orientation of budgets in 2022

Breakdown of spending by DAC members by sectors, allowing for analysis of any sectoral re-allocation of budgets to address ongoing and changing needs

In addition to the emergency response to conflict and crises that marked 2022 and the beginning of 2023, international attention in the second half of the year is likely to be on systemic development and climate concerns. A recent UN report noted that only 12% of the Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDG) targets are on track, and member states are encouraged to deliver USD 500 billion per year up to 2030 as an SDG stimulus (UN, 2023[66]). At the UN General Assembly in September 2023, member states will be asked to recommit to the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on financing for development, and in the same month, the UN Secretary General will convene a climate summit (Reuters, 2022[67]). A transitional committee established at COP27 to advise on the operationalisation of the agreed Loss and Damage Fund is expected to report at COP28 in December, and further progress towards a new collective quantified goal on climate finance in 2024 is expected (UNFCCC, 2022[68]). Against this backdrop, the composition and levels of in-donor refugee costs remain uncertain (see How have DAC members responded to escalating in-donor refugee costs?), ongoing support to and reconstruction of Ukraine will continue to require policy attention and financing, while the need to find solutions for high levels of debt in developing countries is unlikely to abate.

Ongoing support to and reconstruction of Ukraine will continue to require attention in 2023

Several countries have signalled that they intend to provide the same amount of aid to Ukraine in 2023 as in 2022. From 16 January to 24 February 2023, EUR 12.96 billion were committed to Ukraine (Kiel Institute, 2023[20]). Though this is a decline in new pledges from December 2022, it indicates that spending in response to Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine is likely to continue affecting ODA budgets in 2023.

After the first year of the war (February 2022-February 2023), estimates for the cost of reconstruction and recovery in Ukraine stood at USD 411 billion over ten years – twice the size of Ukraine’s pre-war economy in 2021 (World Bank, 2023[69]). Needs in 2023 are around USD 14 billion, for which USD 3.3 billion has been allocated from Ukraine’s state budget and USD 5.1 billion is earmarked as donor opportunities, with the remainder expected to come from the private sector (World Bank, 2023[69]) (Government of Ukraine, 2023[70]). Domestic resource mobilisation remains critical to state coffers and fluctuates depending on territory made inaccessible due to incursion. Financing priorities for 2023 are energy infrastructure, humanitarian demining, housing, critical and social infrastructure, and support for the private sector. While the initial National Recovery Plan set out by Ukraine in July 2022 envisaged partner grants covering 40% of funding needs in 2023-25 (National Recovery Council, 2022[71]), reconstruction estimates come with a warning that the scale of investment required will necessitate leveraging limited public and donor funding to encourage private investment, and that the use of concessional finance should be prioritised carefully to avoid being overwhelmed by short-term needs (World Bank, 2023[69]).

Reconstruction estimates come with a warning that the use of concessional finance should be prioritised carefully to avoid being overwhelmed by short-term needs.

Multilateral organisations have taken the lead in co-ordinating support to Ukraine and innovating to meet needs (Multilateral partners co-ordinate efforts and innovate to leverage collective resources). Given the scale and long-term nature of financing required, their access to resources and financial instruments, and their ability to aggregate, share and offset risks will be vital for Ukraine and members looking for appropriate mechanisms to channel their support. The Lugano Declaration and Principles – partnership, reform-focus, transparency, accountability and rule of law, democratic participation, multistakeholder engagement, gender equality and inclusion, and sustainability (Ukraine Recovery Conference, 2022[72]) – provide a sound basis for co-ordinated support. The long-standing Effectiveness Principles of country ownership, focus on results, inclusive partnerships, and transparency and mutual accountability can also guide co-ordination and response efforts (GPEDC, 2011[73]).

Multilateral organisations have played a dual role in supporting Ukraine since the war began: (1) co-ordination of international support and (2) leveraging their access to markets, financial resources, and range of financial instruments to provide direct support to Ukraine. Efforts include:

The EU facilitated several international conferences relating to Ukraine’s recovery, including in Lugano (July 2022), Berlin (October 2022), and Paris (December 2022). The next conference is due to take place in London in June 2023.

In addition to providing direct support, the EU facilitated the January 2023 launch of a Multi-agency Donor Co-ordination Platform to support Ukraine’s repair, recovery, and reconstruction. The platform’s steering committee is co-chaired by the governments of Ukraine, the US, and the European Commission, and attended by representatives of G7 countries and international financial institutions.

EU loans to Ukraine have been sizeable and innovative. Through the MFA+ instrument, the EU borrows funds on capital markets backed by guarantees from the EU budget. In addition to reform conditions, such as the establishment of a financial reporting system, the loans are on highly favourable terms (35-year maturity with a 10-year grace period) and interest-rate and administrative costs can be subsidised through the EU budget with contributions by members.

The European Investment Bank (EIB) committed EUR 2.26 billion to Ukraine and disbursed EUR 1.7 billion by May 2023. It also put in place a EUR 4 billion credit line to support EU member states with costs associated with welcoming Ukrainian refugees.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is the largest institutional investor in Ukraine, with a portfolio of EUR 4.7 billion. It committed EUR 3 billion in 2022-23 to support Ukraine. Of EBRD financing risk in Ukraine, 50% was shared with donor resources via the EBRD Crisis Response Fund.

Following support for Ukraine under its Rapid Financing Window in March and October 2022, the IMF approved a new four-year Extended Fund Facility (EFF) in March 2023 worth USD 15.6 billion, with immediate disbursement of USD 2.7 billion. The EFF focuses on stability, economic recovery, enhancing governance, and strengthening institutions to promote long-term growth in the context of post-war reconstruction. It expressly intends to mobilise large-scale concessional financing from Ukraine’s international donors to help resolve balance of payments issues and restore debt sustainability. It is the first time that the IMF lent to a country in active conflict. The EFF is part of a USD 115 billion support package from the IMF, involving grants, concessional loans, and debt-relief.

In April 2022, the IMF opened a special Administered Account for Ukraine, for individual donor countries to channel loans or grants, which some countries have availed themselves of.

The World Bank mobilised over USD 23 billion in support, of which USD 20 billion was disbursed by end-April 2023. Grants, loans, and guarantees were provided through a range of channels, including the Ukraine Relief, Recovery, Reconstruction, and Reform Trust Fund (URTF) established in December 2022.

At the end of 2022, the International Finance Corporation launched a USD 2 billion package to support the Ukrainian private sector, of which USD 150 million was disbursed by April 2023. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) issued USD 106 million in guarantees to enable additional lending.

Note: The amounts quoted above are correct as of early May 2023. Where bilateral resources are channelled through multilaterals, amounts might overlap with bilateral commitments discussed in earlier sections of the chapter and should not be aggregated.

Source:https://decentralization.gov.ua/uploads/attachment/document/1060/Lugano_Declaration_URC2022-1.pdf; https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/733763/IPOL_IDA(2023)733763_EN.pdf; https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/03/31/pr23101-ukraine-imf-executive-board-approves-usd-billion-new-eff-part-of-overall-support-package; https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ukraine/brief/world-bank-emergency-financing-package-for-ukraine#:~:text=Since%20February%202022%2C%20the%20World,(April%2027%2C%202023); https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/region__ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/europe+and+central+asia/priorities/ukraine; https://www.miga.org/press-release/miga-supports-ukrainian-financial-sector-resilience-new-guarantee; (Government of Ukraine, 2023[70]); (IMF, 2023[74])

Reconstruction efforts will likely generate significant contracting opportunities. Ukraine is not among the countries covered by the DAC Recommendation on Untying official development assistance.17 However, some DAC members already untie all of their aid, regardless of whether the destination is covered under the recommendation (OECD, 2023[54]). ODA support to Ukraine could consider such practice, particularly considering the prevalence of multi-donor efforts.

Private finance is also expected to play a role in Ukraine’s support and reconstruction. At the beginning of the invasion, for example, Ukraine issued war bonds which were primarily purchased by local banks and private citizens, thanks to the re-purposing of its COVID-19 app to facilitate transactions (The Washington Post, 2022[75]). That Ukraine’s government debt is largely held by domestic banks reduces risks from external creditors, and helpfully major private-sector creditors agreed to a temporary debt-service suspension for Ukraine (European Parliament, 2023[24]). Efforts were being made in Spring 2023 to mobilise additional private investment for Ukraine, for example through a Memorandum of Understanding between the US International Development Finance Corporation, USAID and the Government of Ukraine (U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, 2023[76]). In response to numerous downgrades of Ukraine’s credit rating since the beginning of the war (OECD, 2023[12]) Germany’s government is providing investment guarantees (European Business Association, 2023[77]) and G7 nations are leveraging their Export Credit Agencies to underwrite Ukrainian business opportunities (Government of the United Kingdom, 2023[78]).

Ukraine’s government has emphasised the importance of private-sector investment, including suggesting war-risk insurance mechanisms supported by bilateral and multilateral partners as a way to attract private-sector investment (Government of Ukraine, 2023[79]). Private finance mobilised by DAC countries for Ukraine was USD 56 million in 2021; it has ranged over the past decade from a low of USD 9 million (2015) to a high of USD 760 million (2017).

Responding to escalating and complex debt, particularly in low-income countries

As of February 2023, 53 ODA-eligible countries were at moderate or high risk of debt distress and nine were already in distress (IMF, 2023[80]). Borrowing to fund responses to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the largest proportion of public debt in six decades, raising concerns about debt vulnerabilities particularly in low- and middle-income countries (IMF, 2022[81]). The strong dollar and rapid raising of interest rates to contain inflation make servicing US denominated debt more expensive and borrowing on markets more difficult (OECD, 2023[54]) (IMF, 2023[82]). African currencies have depreciated significantly and remain under pressure (IMF, 2023[83]).

The composition of debt in developing countries changed significantly since the debt cancellation movements of the early 2000s. Bondholders and other private creditors now hold the highest levels of developing-country debt, followed by multilaterals (Reuters, 2023[84]). China is now the largest bilateral lender to developing countries, outstripping all Paris Club bilateral lenders combined (Reuters, 2023[84]). Recent analysis found that 22 debtor countries received USD 240 billion in Chinese rescue lending (Central Bank Swap Lines18 and rescue loans) since 2000 (Horn et al., 2023[85]). The majority of this assistance was made available in recent years, aligning with China’s rise as an important creditor, and to low- and middle-income countries already heavily indebted to China – essentially preventing default on Chinese debt already extended (Horn et al., 2023[85]) (see Annex C). The growing use of central bank swap lines can further complicate debt transparency and reporting (Horn et al., 2023[85]).

Eight of the nine countries in debt distress are in Africa, and experience in the region illustrates the trends described above. New lending rose from around USD 10 billion in 2000 to over USD 80 billion in 2020 (Mihalyi and Trebesch, 2023[86]). While the level of public debt has not reached the peaks of the early 1990s or 2000s, it is now dominated by domestic rather than external debt (FinDevLab, 2023[87]), with bonds the largest source. Chinese creditors now hold 17% of external debt in sub-Saharan Africa, the highest proportion in any region (OECD, 2023[12]). In 2022, the region had the highest yields on government bonds at 7.9% against an average of 5.3% for all developing countries (OECD, 2023[12]). Though private lending levelled off during the COVID-19 period (World Bank, 2023[88]), the high costs of repayments – an average of 6.2% – to private-sector lenders (Africa’s debt landscape is increasingly heterogenous) are causing significant issues for African countries (Mihalyi and Trebesch, 2023[86]).

As of 2018,19 bilateral ODA loans from DAC countries accounted for only an average 4.1% of total external debt stock in partner countries in Africa. In contrast to high rates for private lending, the average interest rate for bilateral creditors (excluding China) was 1.3% with 24.7-year maturity (Africa’s debt landscape is increasingly heterogenous). ODA lending in 2021 had an even lower average interest rate of 1.1% in 2021, but with slightly lower maturity at 21.1 years. Though it has been noted that conditions on ODA lending to LDCs have hardened in recent years, rates and maturities to LDCs remain more favourable than those for LMICs and for LIMCs in comparison to UMICs (OECD, 2023[89]). While the profile of creditors varies across country-income groups (e.g., multilaterals are the most important creditors for low-income countries), countries borrow from the full range of creditors, meaning that they are subject to a wide range of interest rates, and research suggests that a portion of low-cost borrowing is used to pay down higher-cost debts (Mihalyi and Trebesch, 2023[86]).

Research suggests that a portion of low-cost borrowing is used to pay down higher-cost debts

Looking ahead, low-income countries that issue bonds are facing significant re-financing risks with nearly half (42%) of their marketable debt coming due within three years (OECD, 2023[12]). There is also significant variation in debt stocks, sustainability, yields and maturities across developing countries, which DAC members and other development co-operation providers will need to take into account as a key contextual factor in design of country strategies.

Bilateral, multilateral, and private creditors are being called on to make progress with debt restructuring, relief, and swap efforts (Global Development Policy Centre, 2023[90]; UNDP, 2023[91]). Calls for a new financial architecture (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade Barbados, 2022[92]) indicate that long-term solutions will be needed to deal with the complex debt landscape and attempt to avoid such a situation in the future. For example, low-income countries issuing bonds are advised to build out domestic bond markets and increase issuance in local currency (OECD, 2023[12]). To address the high cost of private lending to developing countries, some are calling for a new approach to credit ratings of African countries to make market finance more affordable, freeing up fiscal space (UNDP, 2023[93]). However, the heterogenous debt landscape makes swift action difficult because of the need for co-ordination among creditors. A Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable co-chaired by the IMF, World Bank, and G20 Presidency during the 2023 Spring Meetings brought together Paris Club and non-Paris Club members, debtor countries, and private sector representatives to discuss ways to accelerate debt restructuring (IMF, 2023[94]). This might address frustrations that action under the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatment (CF) has been slow (Georgieva and Pazarbasioglu, 2021[95]). Expectations for improvements were raised, with China indicating that it might drop a demand that multilateral creditors take losses on loans before it would enter CF negotiations with debtor countries that request it (Reuters, 2023[84]). The Summit for a New Global Financial Pact, (Paris, June 2023), focuses on dealing with debt among other topics (Focus2030, 2023[96]).

While ODA lending does not feature heavily in the debt composition of most low- and middle-income countries, DAC-member governments will be key in designing and executing international solutions. ODA providers will need to consider the wider debt landscape in all allocation decisions and be prepared for higher debt levels to drive demand for more concessional finance.

ODA providers will need to consider the wider debt landscape in all allocation decisions and be prepared for higher debt levels to drive demand for more concessional finance.

For the countries with little or no access to markets, for example around half of the countries in SSA did not issue bonds in 202220 (OECD, 2023[12]), the role of ODA and other development finance remains critical. ODA is also uniquely placed to provide support to public financial management and domestic revenue mobilisation to free up fiscal space, particularly noting the drop in government revenue for developing countries in recent years (see Official development assistance to LDCs has been decreasing but remains vital despite an outlook for strong growth).

The annexes provided below compile data on key indicators for DAC members and ODA-eligible countries. This data was compiled from a large range of publicly available international databases (see source notes for full breakdown) and the OECD Creditor Reporting System and DAC Statistics. All data has been made comparable using OECD methods. These tables are downloadable in Excel Workbook format at https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-cooperation-report/

References

[3] Ahmad, Y. et al. (2020), “Six decades of ODA: insights and outlook in the COVID-19 crisis”, in Development Co-operation Profiles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5e331623-en.

[1] Ahmad, Y. and E. Carey (2022), “How COVID-19 and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine are reshaping official development assistance (ODA)”, in Development Co-operation Profiles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/223ac1dd-en.

[2] Ahmad, Y. and E. Carey (2021), “Development co-operation during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of 2020 figures and 2021 trends to watch”, in Development Co-operation Profiles, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e4b3142a-en.

[14] Carey, E. and H. Desai (2023), Maximising official development assistance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/cecd8a6c-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/cecd8a6c-en#.

[38] DAC-CSO Reference Group (2023), It’s not enough and it’s not ODA, https://www.dac-csoreferencegroup.com/post/it-s-not-enough-and-it-s-not-oda-with-global-crises-growing-in-scale-and-severity-oda-levels-must (accessed on 1 May 2023).

[32] EUAA (2023), Almost 1 million asylum applications in EU+ in 2022, https://euaa.europa.eu/news-events/almost-1-million-asylum-applications-eu-2022#:~:text=New%20analysis%20released%20by%20the,were%20lodged%20in%20EU%2B%20countries.

[77] European Business Association (2023), The German Government provides guarantees for new German investments in Ukraine - European Business Association, https://eba.com.ua/en/nimetskyj-uryad-nadaye-garantiyi-dlya-novyh-nimetskyh-investytsij-v-ukrayinu/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[48] European Council (2023), How the Russian invasion of Ukraine has further aggravated the global food crisis - Consilium, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/how-the-russian-invasion-of-ukraine-has-further-aggravated-the-global-food-crisis/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

[24] European Parliament (2023), “Multilateral financial assistance to Ukraine”.

[31] Eurostat (2023), Asylum applicant by type of applicant, citizenship, age and sex, monthly data, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/MIGR_ASYAPPCTZM__custom_627198/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=1e12e794-fd27-476a-a6d0-76adbeef12ad (accessed on 5 May 2023).

[47] FAO (2022), FAO Food Price Index | World Food Situation | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

[87] FinDevLab (2023), African perspectives on the current debt situation and ways to move forward - FinDevLab, https://findevlab.org/african-perspectives-on-the-current-debt-situation-and-ways-to-move-forward/ (accessed on 4 May 2023).

[96] Focus2030 (2023), Summit for a New Global Financial Pact: towards more commitments to meet the 2030 Agenda?, https://focus2030.org/Summit-for-a-New-Global-Financial-Pact-towards-more-commitments-to-meet-the-1030 (accessed on 4 May 2023).

[49] FSIN and Global Network on Food Crises (2023), 2023 Global Report on Food Crises, https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/GRFC2023-compressed.pdf.

[95] Georgieva and Pazarbasioglu (2021), The G20 common framework for debt treatments must be stepped up.

[90] Global Development Policy Centre (2023), Report: Guaranteeing Sustainable Development – Debt Relief for Green and Inclusive Recovery, https://drgr.org/our-proposal/report-guaranteeing-sustainable-development/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[42] Government of the Netherlands (n.d.), Dutch aid for Ukraine: from day to day, https://www.government.nl/topics/russia-and-ukraine/dutch-aid-for-ukraine (accessed on 26 May 2023).

[78] Government of the United Kingdom (2023), Heads of G7 Export Credit Agencies – Joint Statement Expressing Support for Ukraine - GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/heads-of-g7-export-credit-agencies-joint-statement-expressing-support-for-ukraine (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[70] Government of Ukraine (2023), Second meeting of the steering committee from the multi-agency donor coordination platform for Ukraine, https://mof.gov.ua/en/news/second_meeting_of_the_steering_committee_for_the_multi-agency_donor_coordination_platform_for_ukraine-3922 (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[79] Government of Ukraine (2023), War risk insurance mechanisms should be launched to attract investors to Ukraine: Yuliia Svyrydenko in Brussels, https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/dlia-zaluchennia-investoriv-v-ukrainu-treba-zapustyty-mekhanizmy-strakhuvannia-voiennykh-ryzykiv-iuliia-svyrydenko-u-briusseli.

[73] GPEDC (2011), The Effectiveness Principles, https://effectivecooperation.org/landing-page/effectiveness-principles.

[85] Horn, S. et al. (2023), China as an International Lender of Last Resort, https://d1e00ek4ebabms.cloudfront.net/production/uploaded-files/China%20as%20an%20International%20Lender%20of%20Last%20Resort-66b326f5-bbb0-4ab7-bee0-919453685b0b.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[39] ICAI (2023), UK aid funding for refugees in the UK - ICAI, https://icai.independent.gov.uk/review/uk-aid-funding-for-refugees-in-the-uk/review/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

[46] IEA (2022), Key findings – Africa Energy Outlook 2022 – Analysis - IEA, https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2022/key-findings (accessed on 16 May 2023).

[50] IFPRI (2023), The Russia-Ukraine war after a year: Impacts on fertilizer production, prices, and trade flows | IFPRI : International Food Policy Research Institute, https://www.ifpri.org/blog/russia-ukraine-war-after-year-impacts-fertilizer-production-prices-and-trade-flows (accessed on 16 May 2023).

[83] IMF (2023), African Currencies Are Under Pressure Amid Higher-for-Longer US Interest Rates, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/05/15/african-currencies-are-under-pressure-amid-higher-for-longer-us-interest-rates.

[11] IMF (2023), Europe’s Knife-Edge Path Toward Beating Inflation Without a Recession, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/04/28/europes-knifeedge-path-toward-beating-inflation-without-a-recession (accessed on 2 May 2023).

[74] IMF (2023), FAQ, https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/ukraine#Q5.%20Is%20it%20the%20first%20time%20that%20the%20IMF%20is%20lending%20to%20a%20country%20in%20active%20conflict?.

[82] IMF (2023), Global Financial Stability Report, April 2023, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2023/04/11/global-financial-stability-report-april-2023?cid=bl-com-spring2023flagships-GFSREA2023001 (accessed on 9 May 2023).

[94] IMF (2023), Global Sovereign Debt Roundtable Co-Chairs Press Statement, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/04/12/pr23117-global-sovereign-debt-roundtable-cochairs-press-stmt (accessed on 17 May 2023).

[80] IMF (2023), List of LIC DSAs for PRFT-Eligible Countries, As of February 28, 2023, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dsa/dsalist.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[52] IMF (2023), Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa, April 2023, International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C., https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/SSA/Issues/2023/04/14/regional-economic-outlook-for-sub-saharan-africa-april-2023.

[13] IMF (2023), World Economic Outlook, April 2023: A Rocky Recovery, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2023/04/11/world-economic-outlook-april-2023 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

[81] IMF (2022), In Focus | IMF Annual Report 2022, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/2022/in-focus/debt-dynamics/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[17] IMF (2022), Macroeconomic Developments and Prospects in Low-Income Countries - 2022, International Monetary Fund, Washington D.C., https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2022/12/07/Macroeconomic-Developments-and-Prospects-in-Low-Income-Countries-2022-526738.

[55] IMF (2022), Russia’s war in Ukraine could raise poverty in Caucasus, Central Asia.

[20] Kiel Institute (2023), Ukraine Support Tracker | Kiel Institute, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/ (accessed on 27 February 2023).

[41] KPMG (2021), Evaluation of in-donor costs for asylum seekers and quota refugees in Iceland, https://www.government.is/library/01-Ministries/Ministry-for-Foreign-Affairs/Int.-Dev.-Coop/Evaluations/Evaluation%20of%20in-donor%20costs%20English%20version.pdf.

[7] Melonio, T., R. Rioux and J. Naudet (2022), Official Development Assistance at the Age of Consequences | AFD - Agence Française de Développement, https://www.afd.fr/en/official-development-assistance-age-of-consequences-melonio-naudet-rioux (accessed on 19 October 2022).

[86] Mihalyi, D. and C. Trebesch (2023), “Who Lends to Africa and How? Introducing the Africa Debt Database”, Kiel Working Papers, Vol. 2217, https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/kiel-working-papers/2022/who-lends-to-africa-and-how-introducing-the-africa-debt-database-17146/ (accessed on 3 May 2023).

[92] Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade Barbados (2022), The 2022 Bridgetwon Initiative.