Introduction

On 14 February 2017, the Polish Council of Ministers adopted a new development strategy for the country. The Strategy for Responsible Development (SRD) (Government of Poland, 2017[1]) endorses more balanced growth across the entire Polish territory. It sets out development policy guidance for the short term through 2020 and identifies objectives and approaches for the medium term through 2030. While the SRD sets out a picture of how Poland should evolve, it does not provide a roadmap for achieving these aspirations.

The SRD ushers in a departure from previous approaches by placing a greater emphasis on coherence, cohesion and support for smaller places – improving the links between small- and medium-sized cities and rural areas – and not just the largest urban centres. In the government’s assessment, the previous model, which concentrated investment in larger cities, has not led to the anticipated diffusion of economic growth to smaller places. Under the SRD, the proposed strategy is to target support to both leading and lagging areas. Effective management practice and appropriate governance frameworks will be critical to realising these objectives.

At the request of the Polish Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy (MDFRP) and in close collaboration with the Association of Polish Cities (APC), the OECD conducted a public governance and territorial development assessment targeted at two types of Polish local self-government units (LSGUs) - municipalities (gminas) and counties (powiats) on how to strengthen their local self-government capacity. The ultimate objective of this project, entitled Better Governance, Planning and Services in Local Self-Governments in Poland, is to better serve citizens, enhance local sustainable development and engage with stakeholders to build a collective vision and actions using good governance methods based on international best practice. One of the aims is therefore to strengthen the design and implementation of local self-government units’ medium-/long-term development strategies (thereby contributing to the achievement of the national SRD). The project was funded under the European Economic Area (EEA) and Norway Grants Financial Mechanism within the Local Development Programme 2014-21 implemented by the Polish Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy.

The project analyses local policy and practice in the eight key thematic areas of public governance and territorial development outlined below and presents an assessment of LSGU capacity in these areas along with recommendations for reforms. It is important to note that these themes represent interdependent and mutually reinforcing building blocks for good public governance and to achieve balanced territorial development. Taken as a whole, they constitute a means to serve citizens better: to improve results and outcomes for people, businesses and places. Crosswalks and linkages between the thematic chapters are therefore reflected in the recommendations that are presented as integrated elements of a coherent approach to improving public governance and territorial development. Besides the eight thematic chapters, an additional chapter provides a diagnosis of the main economic, social and demographic trends, strengths and challenges in Polish LSGUs and their effects on local development. The eight key thematic areas are:

1. Co-ordination across administrative units and policy sectors within LSGUs

3. The use of evidence in strategic decision-making in LSGUs

5. Strengthening multi-level governance and investment capacity to enhance local development

6. Toward a more strategic and effective local self-government workforce

8. Reducing administrative burden and simplifying public procurement

The primary focus of the project is the local level of self-government in Poland (municipalities and counties); however, LSGUs in Poland do not operate in a vacuum but a system of close interaction with regional and national governments. This report thus includes analyses of the multi-level governance system in Poland, wherever it is appropriate, to reveal how the mutual dependency across levels of government influences or affects the governance and development capacity of LSGUs. Through actionable recommendations, the project aims to contribute to sustaining dialogue on how specific reforms can improve performance in meeting the needs of citizens, by providing OECD data and a comparative analysis of public governance, management, institutional arrangements, budgeting, financing and policy-making practices in Polish LSGUs.

Due to the large diversity among Polish municipalities and the considerable differences between their respective situations and related challenges, the OECD’s analysis and advice provided in the main report is supplemented by three synthesis assessments. By distinguishing between three different types of municipalities (following the OECD’s classification of Polish municipalities explained below), these separate assessments summarise the report’s findings for each type of municipality and offer a greater level of granularity based on measurable characteristics that can help identify particular challenges and opportunities.

In addition, the OECD also accompanies and supports Polish LSGUs in strengthening their capacity to design and implement successfully their multi-dimensional and integrated strategic development strategies, through the design of a self-assessment tool. This tool details key indicators for Polish LSGUs to assess their main strengths and gaps on public governance and local development practices. Through its thematic focus on specific areas of good governance and territorial development, the tool also enables capacity-building that can be scaled up and out across LSGUs so that they can self-assess their own capacity to design and implement effective integrated development strategies and action plans in a manner that reflects OECD-wide standards and good practices.

The first part of this introductory chapter focuses on the creation of the project’s evidence base and the OECD’s methodology for the report. It is further explained how the report links to other OECD projects with Poland in the areas of public governance and territorial development. Poland’s territorial structure and administrative system are explained in the second part of this chapter. The third part introduces a revised territorial classification for Polish municipal LSGUs that the OECD uses for this report.

In order to collect information and data on public governance and territorial development at the local level in the Polish context, the OECD developed a comprehensive, composite questionnaire. The objective of this questionnaire was to obtain data, information and evidence on LSGU practice in the different thematic areas assessed and analysed in this project. The questionnaire was discussed with representatives of more than 120 local, regional and national governments in October 2019 and administered to a representative sample of LSGUs and a series of regional and national governments by the APC. The responses these governments provided enabled the creation of a solid evidence base for the report’s analysis that was a key contributor to assessing Polish practice against OECD standards. The following institutions responded to the questionnaire:

Regional level: 8 voivodeship offices and 12 marshal offices.

National level: 7 ministries and other national institutions.

While the size of the questionnaire response sample does not allow to draw statistically relevant conclusions, it nevertheless offers sample-specific insights that may be relevant for a larger audience of Polish LSGUs. Following the OECD’s established methodology, the data collection process for this report was also based on four fact-finding missions (FFMs) to Poland, the purpose of which was to conduct extensive interviews with a wide variety of stakeholders at the local, regional and national level. The institutions interviewed during these missions were jointly selected by the APC and the MDFRP in consultation with the OECD. The 9 LSGUs and the Metropolitan Association of Upper Silesia and Zagłębie (Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowska Metropolia (GZM Metropolis)) in Katowice that were visited during the first three FFMs reflect diversity in terms of economic performance, geographic location (e.g. proximity to the economic centres of the country) as well as regarding their size of the population, among other criteria. During each mission, the OECD conducted interviews with relevant LSGU representatives, civil society organisations, academics and private sector representatives to discuss public governance and territorial development issues with key stakeholders. This sample of LSGUs together with the information provided by a broad range of municipalities and counties (as well as institutions at the regional and national level) in the questionnaire allows to scale up and replicate the report’s recommendations across LSGUs not included in the sample.

Mission 1: During the first fact-finding mission, the OECD team travelled to the three LSGUs of Katowice, Krotoszyn and Ziębice and visited the Metropolitan Association of Upper Silesia and Zagłębie (Górnośląsko-Zagłębiowska Metropolia (GZM Metropolis)).

Mission 2: During the second FFM, the OECD team visited the four LSGUs of Łańcut (county), Łubianka, Międzyrzec Podlaski (rural municipality) and Międzyrzec Podlaski (urban municipality).

Mission 3: Due to the exceptional circumstances related to the evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting limitations to travel, the third FFM took place virtually. Online interviews covered the two LSGUs of Kutno and Płock.

Mission 4: During the fourth mission focused on the regional and national level of government, the OECD team conducted online interviews with representatives of the two voivodeships Lubelskie (Lubelskie Marshal Office, Lubelskie Voivodeship Office) and Śląskie (Śląskie Marshal Office, Śląskie Voivodeship Office) as well as national institutions: 8 ministries (Chancellery of the Prime Minister, Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Ministry of Development, Ministry of Digital Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Infrastructure, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration) and national agencies (Statistics Poland, National Institute of Local Self-Government, Office of the Ombudsman, Public Procurement Office, Supreme Audit Office) in Poland.

Both the draft assessment as well as the preliminary advice and recommendations were discussed during a virtual sounding-board mission with more than 170 different stakeholders from all three levels of government in January 2021. As a result of these consultations, the present report has benefitted from the written input of comments from the following entities:

Applying its peer-based approach, the OECD organised a workshop in June 2021 with country peers – senior officials from national, regional and local levels of government in OECD countries, who have faced or are facing the same challenges as those being assessed in the report. The workshop for representatives of LSGUs, regional self-governments and ministries served as a means to disseminate the report’s findings, share good practice examples of other OECD countries and generate ideas on possible courses of action in Poland to address the public governance and territorial development challenges under review.

The Better Governance, Planning and Services in Local Self-Government Units: Poland report builds on numerous collaborations between Poland and the OECD. The OECD Rural Policy Reviews: Poland 2018 (2018[2]) examines the range of policies impacting rural development in Poland. It offers recommendations on how to support economic diversification of rural areas, boost agricultural productivity, enhance inter-municipal co-ordination, deepen decentralisation and improve multi-level governance.

The Public Governance Review of Poland Poland: Implementing Strategic-State Capability (2013) (OECD, 2013[3]) proposes a practical, country-based framework for developing good governance indicators for programmes funded by the European Union (EU) in Poland.

The Urban Policy Review of Poland (2011) (OECD, 2011[4]) looks at the urban system and the challenges it faces, national policies for urban development in Poland and adapting governance for a national urban policy agenda. In that regard, the OECD also conducted the report on the Governance of Land Use in Poland: The Case of Łódź (2016) (OECD, 2016[5]).

Finally, by exploring the various challenges and opportunities for Polish regional development policy, the OECD Territorial Review of Poland (2008) (OECD, 2008[6]) provides recommendations to best design and implement the policy mix, looking in particular at multi-level governance challenges.

The present report also reflects the public governance recommendations presented in the 2016 OECD Better Policies Brochure on Poland (OECD, 2016[7]), linking the country’s approach to development with its efforts to implement the UN Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

An administrative structure with strong historical roots

Since 1989, with the restoration of independence and democracy, the Polish territorial structure and multi-level governance system have strongly evolved. After 45 years of centralisation, Poland has pursued political and fiscal decentralisation reforms and the scope and role of subnational governments in policy delivery have increased significantly in the last years. The principle of local self-government represents one of the pillars of Poland’s transition from the communist era to democracy. The process of decentralisation is often recognised as one of the most successful aspects of this transition (Baro Riba and Mangin, 2019[8]). However, the decentralization process has not been implemented without difficulties due to the high value conferred to the central state, seen as a guarantee of the homogeneity of the national territory. Indeed, even though the country borders were so often changed during the recent last two centuries, the notion of “territory” is deeply anchored in the national memory (Assembly of European Regions, 2017[9]; OECD, 2020[10]).

The first legislative package of local democracy and autonomy of municipalities (gminas) was enacted in 1990 resulting in the first democratic elections of almost 2 500 local councils in May of that year. The law on local prerogatives, adopted in March 1990, was achieved by restoring the former subregional units, which were abolished by the communist government in 1975 (Assembly of European Regions, 2017[9]). This law delivered more strategic capacities to LSGUs and gave them large responsibilities in terms of spatial planning, infrastructure development, utilities, municipal housing, social services, education, environmental protection, basic healthcare and recreation and culture. However, this dynamic was not accompanied by a transfer of funds (OECD, 2020[10]).

In Poland, the second wave of decentralisation (regionalisation) reforms took place in 1998-99. For regionalisation reforms, the core debate related to the number of voivodeships. Most stakeholders understood the necessity of reducing the size of the regions to restore the historical intermediary level, the county (powiat), abolished in 1975. Finally, the legislative package enacted in January 1990, restored the county as another subnational tier of local self-government (i.e. supra-municipal), which was traditional in Poland, and created 16 self-government voivodeships (regions) managed by Marshals that replaced 49 former small voivodeships managed by the national administration (Sześciło, Dawid and Kulesza, Michał, 2012[11]).

Since the first election of county and voivodeship councils in 1999, Poland has a three-tier system of subnational governments, where municipalities and counties perform the functions of local governments. The 16 voivodeships, which form the largest territorial division of administration in the country, respond to tradition and historical administrative divisions, resulting in a system of territorial governments that society could approve (Sześciło, Dawid and Kulesza, Michał, 2012[11]). What is remarkable about the system’s architecture is the capacity that is left for all levels to be independent from the other. Such a feature complies with the very historical legacy of freedom of the administrative levels in the country but has very often been blamed for fostering paralysis and blockage (OECD, 2020[10]).

The often-recognised successful implementation of decentralisation reforms in the country is partially due to the way it was designed, with a large involvement of a wide range of stakeholders. Polish authorities organised important public discussions before the adoption of the law, representing an important period of deep democratic debate. A large spectrum of participants was invited to discuss and the arguments used were often drawn from the national and local past. During these debates, it was also interesting to see how the local people had a clear idea of their own regional interest and identity. As a result, the law was passed expediently in July 1998.

While the role of voivodeships has been progressively strengthened with the decentralisation of new tasks, it is still limited when compared with regions of other OECD countries. Since 2007, voivodeships are fully responsible for a big share of European Union cohesion funds. In January 2009, the Act on Voivodeship and Governmental Administration in Voivodeship (Government of Poland, 2009[12]) was passed to strengthen and devolve greater powers to Poland’s regions in the areas of transport and environment. Since then, discussions are ongoing regarding reform of funding mechanisms, the introduction of financial incentives for mergers, the design of cost-cutting and efficiency programmes and the creation of metropolitan governance bodies. However, regional government spending remains among the lowest in the OECD area (together with New Zealand and Turkey), representing 0.7% of gross domestic product (GDP) and 1.6% of public spending compared to 3.7% and 8.7% respectively on average for OECD unitary countries (OECD, 2020[13]).

The current administrative and territorial organisation of regions and municipalities

Poland’s regional and local self-government levels are relatively new. As explained in the previous section, a series of decentralisation reforms (in 1990 and 1998) after the end of the communist era led to the first municipal elections and the creation of the regional and local self-government unit levels (OECD, 2018[2]). The regional self-government level is formed by 16 regions/voivodeships (województwo), while the local self-government level is formed by counties (powiats) and municipalities (gminas). Such governance/decentralisation reforms provided subnational self-government units with an increasingly important role in the provision of infrastructure and services.

Inspired by the Finnish and French systems, among others, Poland has a dual system - both decentralised and deconcentrated. It is deconcentrated as the national government has a representative (the voivode) in each of 16 voivodeships. Similar to the prefect in the French system, the voivode is politically appointed by the prime minister and heads the voivodeship office. The voivode is mainly in charge of the ex post control of public funds and safety provision. At the same time, the system is decentralised as the 16 voivodeships have their own authority as regional self-governments. They are headed by the marshal (president of the region), who is a political figure elected by the voivodeship assembly. The marshal sets and drives the regional policy of the whole voivodeship, organises the tasks of the marshal office and represents the voivodeship externally. The marshal office, a self-governing organisation in the voivodeship, is a body executing the tasks designated by the marshal and the voivodeship’s elected members.

At the intermediate level of government, one finds the county (powiat), which is a local self-government unit led by the head of the county (starosta). The head of the county is elected by the county council and is responsible for driving the development of the county within the framework of the regional development strategy of the voivodeship.

The lowest level of government in Poland is the municipality (gmina), the LSGU that benefits from a right to develop its own development strategy. According to the Law on the Principles of Implementing Development Policy (2020), the strategy can be developed by a single municipality or jointly by a group of municipalities that create a supra-local development strategy in order to improve co-ordination. The municipality is responsible for all public matters of local importance in its territory, including local public transport, electricity, waterworks, health, education, housing, etc. The municipal office is headed by the mayor or president (a formal title depending on the type and size of municipalities but with no difference in competences) who is elected by citizens. The entire territorial organisation of subnational government units in Poland is described in Figure 0.1.

The geographical lens through which policy issues are defined determines the effects of policy actions at the local level. However, territorial definitions often rely on administrative or legal boundaries that do not necessarily reflect the functional and economic interactions within the territory. Capturing settlement patterns and agglomeration economies in a country requires going beyond administrative areas.

This section presents the current territorial classification of Polish territorial units, as well as a revised territorial classification based on the OECD territorial and functional urban area (FUA) typology. This functional definition of territorial units can guide governments at different levels in Poland in identifying common challenges and assets across types of municipalities to help in planning infrastructure, transport, housing, schooling and spaces for culture with the right criteria.

Poland’s territorial classification of municipalities

Poland’s National Official Register of the Territorial Division of the Country (TERYT) on the basis of which the Polish System of Coding of Territorial and Statistical Units (KTS) is based, divides the country into six territorial levels, or seven if we include Poland as a level “0” (Table 0.1). It includes a national administration with a two-tier system, a two-tier system, a national government based in the capital and delegated authorities of the national government to the voivodeships (i.e. 16 voivodeship offices – 1 in each of the 16 voivodeships). Poland also has a self-government administration with a three-tier system with a regional and two local levels of government. At the regional level it is composed of 16 voivodeships (regional self-government units in regions). At local level it consists of two types of local self-government units (LSGUs):

380 counties (LSGUs at the county level in all of the 16 voivodeships and, including 314 counties and 66 cities with county status);

2 477 municipalities (LSGUs at the municipal level in each of the 16 voivodeships).1

The lowest administrative level, the municipality, is divided into three categories: urban, rural and mixed (urban-rural). Since 2020, rural municipalities account for most of the municipalities (62%), above the number of mixed (26%) and urban (12%) municipalities. According to the official Polish categorisation, rural areas comprise rural municipalities and the rural parts of mixed municipalities, while urban areas comprise urban municipalities and the urban part of mixed municipalities.

The average number of inhabitants per municipality in Poland (15 507 in 2018) is above the average in OECD (9 700 inhabitants) and EU (5 880 for the 28 countries) countries. Polish municipalities have on average about 3 times more land area (123 square kilometres) than the average of EU municipalities (49) yet are smaller when compared to the OECD average (211). In contrast with OECD and EU averages, Poland has a relatively lower share of municipalities with fewer than 5 000 inhabitants (26% vs. 44% in the OECD and 48% in the EU) with most Polish municipalities (60%) being medium-sized administrative units (5 000 to 20 0000 inhabitants).

The OECD’s territorial classification of municipalities in Poland

The current territorial classification in Poland is based on qualitative criteria and does not differentiate among different types of rural municipalities. Moving forward, this section introduces a revised territorial classification for Polish municipalities used for this report, which leverages a functional approach by applying the OECD territorial and FUA typology.

In order to capture the functional interactions across the territory, the report uses the FUA definition, which was developed by the European Commission (EC) and the OECD (Box 0.1). Functional Urban Area (FUAs) consists of a densely inhabited core and its commuting zone whose labour market is highly integrated with the core. FUAs are powerful tools to compare socio-economic and spatial trends in cities (Box 0.1). FUAs often have a large internal market, driven by higher-value globally connected services, while areas outside FUAs have different degrees of rurality and higher reliance on primary sectors. According to the OECD typology, Poland has 58 FUAs (Figure 0.2), where the large majority (37) are small FUAs (less than 250 000 inhabitants) and the rest (21) are medium- and large-sized FUAs (with more than 250 000 inhabitants) (Table 0.2). This large number of small- and medium-sized FUAs underlines the dispersed nature of Poland’s settlement structure. TL3 regions cover the entire territory within countries, while Functional Urban Areas (FUAs) only capture a sub-sample of the territory.

The EU and the OECD have jointly developed a methodology to define FUAs, which consists of a core of FUA and their commuting zones in a consistent way across countries. A FUA can be defined in four steps:

1. Identify an urban centre: a set of contiguous, high density (1 500 residents per square kilometre) grid cells with a population of 50 000 inhabitants in the contiguous cells.

2. Identify a core of the FUAs: one or more local units that have at least 50% of their residents inside an urban centre.

3. Identify a commuting zone: a set of contiguous local units that have at least 15% of their employed residents working in the core of the FUAs.

4. A FUA is the combination of the core with its commuting zone.

The EU-OECD FUA definition ensures that the most comparable boundaries are selected. It does this by first defining an urban centre independently from administrative boundaries. As a second step identifies the administrative boundaries that correspond best to this urban centre. In this way, it ensures that central Paris is compared with all of London or Berlin.

Source: OECD/EC (2020[15]), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation, https://doi.org/10.1787/d0efcbda-en.

To better understand Poland’s territorial trends and facilitate regional comparability across OECD countries, the analysis in this chapter adopts the OECD regional classification (Territorial level 2 (TL2) and Territorial level 3 (TL3) (Box 0.2). This classification identifies two levels of geographic units within OECD countries: i) large regions (TL2), which generally represent the first administrative tier of subnational government; and ii) small regions (TL3). Both levels of regions encompass the entire national territory. Annexe 1.A displays the classification of Poland’s TL3 regions (Box 0.2).

Regions within the 37 OECD countries are classified on 2 territorial levels reflecting the administrative organisation of countries. The 427 OECD large (TL2) regions represent the first administrative tier of subnational government, for example, the Ontario Province in Canada. There are 2 290 OECD small (TL3) regions, with each TL3 being contained in a TL2 region (except for the United States). For example, the TL2 region of Aragon in Spain encompasses three TL3 regions: Huesca, Teruel and Zaragoza. TL3 regions correspond to administrative regions, with the exception of Australia, Canada, Germany and the United States. All the regions are defined within national borders (OECD, 2020[18]).

This classification – which, for European countries, is largely consistent with the Eurostat NUTS 2016 classification – facilitates greater comparability of geographic units at the same territorial level.7 Indeed, these two levels, which are officially established and relatively stable in all member countries, are used as a framework for implementing regional policies in most countries.

The OECD has adopted a new typology to classify administrative TL3 regions based on the presence and access to FUAs (Fadic et al., 2019[19]). The typology classifies TL3 regions into two groups, metropolitan and non-metropolitan regions. Within these two groups, five different types of TL3 regions are identified.

The methodology follows the criteria below:

Metropolitan TL3 regions, if more than 50% of its population live in a FUA of at least 250 000 inhabitants are classified into:

Large metropolitan TL3 regions (large metropolitan regions), if more than 50% of its population lives in a FUA of at least 1.5 million inhabitants.

Metropolitan TL3 regions (metropolitan regions), if the TL3 region is not a large metropolitan region and 50% of its population live in a FUA of at least 250 000 inhabitants.

Non-metropolitan TL3 regions, if less than 50% of its population live in a FUA, are further classified according to their level of access to FUAs of different sizes into:

With access to a metropolitan TL3 region (non-metropolitan regions close to a FUA), if more than 50% of its population live within a 60-minute drive from a metropolitan region (a FUA with more than 250 000 inhabitants); or if the TL3 region contains more than 80% of the area of a FUA of at least 250 000 inhabitants.

With access to (near) a small FUA TL3 region (non-metropolitan regions with/near a small FUA), if the TL3 region does not have access to a metropolitan region. Fifty percent of its population has access to a small FUA (a FUA of more than 50 000 inhabitants and less than 250 000 inhabitants) within a 60-minute drive; or if the TL3 region contains more than 80% of the area of a small or medium FUA.

Remote TL3 region (non-metropolitan remote), if the TL3 region is not classified as the 2 former categories of non-metropolitan regions, i.e. if 50% of its population do not have access to any FUA within a 60-minute drive.

The described procedure leads to more statistical consistency and interpretable categories that emphasise urban-rural linkages and the role of market access. The OECD TL3 typology acknowledges the existence of a rural-urban continuum, with regions being differentiated based on the degree of rurality.

Source: OECD (2020[18])), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/959d5ba0-en; Fadic, M. et al (2019[19]), "Classifying small (TL3) regions based on metropolitan population, low density and remoteness", https://doi.org/10.1787/b902cc00-en.

This OECD territorial classification defines metropolitan TL3 regions non-and metropolitan TL3 regions based on the presence and access to Functional Urban Area (FUAs). Metropolitan regions are the TL3 regions where more than 50% of the population live in a FUA, while non-metropolitan regions have less than 50% of its population living in a FUA.2 This territorial typology acknowledges the existence of a rural-urban continuum, so regions are differentiated based on the degree of rurality, which means that even metropolitan regions have a share of population living in rural places. In addition, the typology uses accessibility as a defining characteristic of regions, taking into account the relative location of rural places with respect to FUAs. As such, it differentiates amongst different types of non-metropolitan regions – those close to cities and those that are remote Box 0.3.

This report uses the OECD/EU methodology of FUAs and the OECD TL2 and TL3 regional classification for international comparisons of Poland’s FUA’s and metropolitan and non-metropolitan regions. All metropolitan regions, non-metropolitan regions close to a FUA, non-metropolitan regions with/near a small FUA and non-metropolitan regions remote are TL3 regions, so the report won’t specify “TL3” when those types of regions are mentioned. Reference will be made to “large FUAs” when referring to FUAs above 1 million inhabitants, “medium FUAs” when referring to FUAs between 250 000 and 1 million inhabitants and “small FUAs” when referring to FUAs below 250 000 inhabitants. Municipalities will be grouped according to the alternative OECD municipal classification proposed for this particular study.

An alternative territorial approach for the classification of municipalities in Poland

To better capture the commonalities among local self-government units in terms of economic opportunities and challenges, the OECD has developed an alternative territorial classification for municipalities in Poland. It classifies municipalities beyond administrative, political and historical reasons and adopts a typology based on economic functionality, population size and accessibility (see more details in Box 0.4).

In Poland, the TERYT classification of municipalities and rural/urban areas is used for official statistics and applied in most academic research and policy analysis in Poland. However, Poland’s territorial typology has scope for improvement as it relies on qualitative criteria to classify urban and rural municipalities and lacks differentiation in the degree of rurality among municipalities, as highlighted in the OECD Rural Policy Review (2018[2]) (Box 0.3).

As identified in the OECD Rural Policy Reviews: Poland (2018[2]), the TERYT classification of municipalities could improve certain aspects:

1. The typology relies on qualitative criteria. Urban status is conferred to municipalities through political (supported by local residents/self-government) and administrative procedures, regardless of quantitative or objective characteristics of the municipalities. The process also involves historical reasons when assigning urban status (cities with county status or the traditional administrative regional centres).

2. There is no differentiation among different types of rural. Rural municipalities with significant linkages with an urban centre are not distinguished from rural municipalities that are remotely located.

3. The “mixed municipality” classification, i.e. urban-rural municipality, creates limitations and distortions for policy analysis and research. Rural parts of mixed municipalities are incorporated into the definition of rural areas. However, certain statistical variables, such as municipal revenue and expenditure as well as the allocation of EU funds, are often not available at this municipality level. Such situation can bias some analyses. For example, the average accessibility of rural dwellers to public services is overestimated because services are often located in the urban part of urban-rural municipalities.

Source: OECD (2018[2]), OECD Rural Policy Reviews: Poland 2018, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264289925-en.

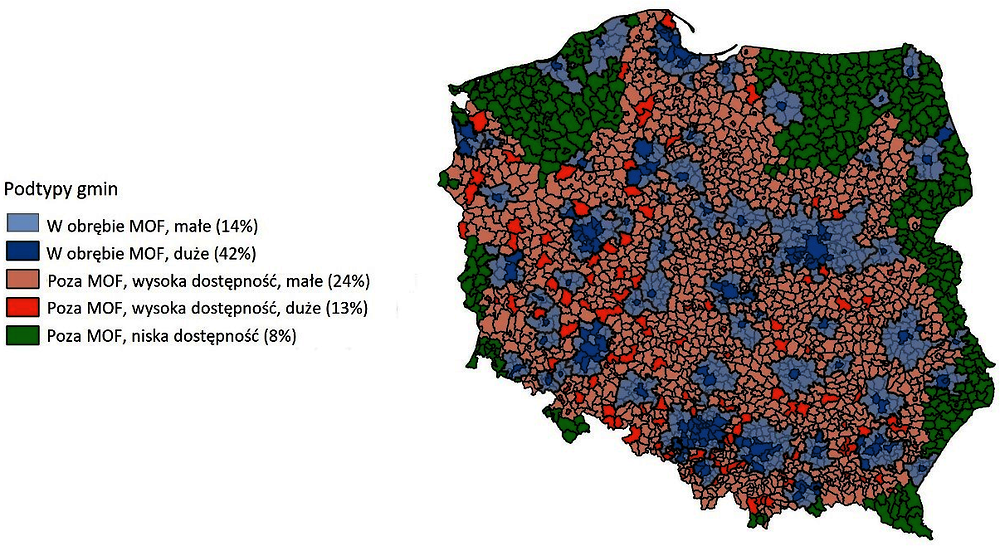

Drawing from the classification of FUAs, the alternative OECD territorial classification for municipalities in Poland identifies three types of municipalities, based on quantitative and functional characteristics (Please see the full methodology in Box 0.4). Some of these types of municipalities are divided in subtypes, according to population size, creating a total of 5 subtypes of municipalities. The following describe the different municipalities according to the OECD alternative territorial classification for Poland (in parenthesis a simplified name that this report will refer to in figures and tables):

2. Municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility:

a. Big municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility (Out FUA high access big): Municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility and more than 20 000 inhabitants. A municipality is classified with high accessibility if the level of population it can reach within a 90-minute drive is above the bottom 10th percentile of the population distribution that all Polish municipalities can reach within a 90-minute drive.

b. Small municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility (Out FUA high access small): Municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility and fewer than 20 000 inhabitants. A municipality is classified with high accessibility if the level of population it can reach within a 90-minute drive is above the bottom 10th percentile of the population distribution that all Polish municipalities can reach within a 90-minute drive.

3. Municipalities outside FUAs with low accessibility (Out FUA low access): Municipalities outside FUAs with low accessibility, regardless of their population size. Some 7% of these municipalities have more than 20 000 inhabitants. A municipality is classified with low accessibility if the level of population it can reach within a 90-minute drive is below the bottom 10th percentile of the population distribution that all Polish municipalities can reach within a 90-minute drive.

The alternative classification follows a three-step process:

1. Identifying municipalities inside and outside FUAs. The methodology identifies municipalities inside and outside FUAs (city and commuting zone).

2. Measuring accessibility for municipalities outside FUAs. The methodology measures the level of accessibility to population settlements by following three steps:

Population within a 90-minute drive around each municipality: it calculates all the population that can be reached from the centroid of each municipality outside FUAs within a 90-minute drive by car in every direction.

Threshold of population reached: It then calculates the bottom 10th percentile of the distribution of the population that all Polish municipalities can reach within a 90-minute drive.

Classify low accessibility and high accessibility municipalities: A municipality is classified with low accessibility if the level of population reached within a 90-minute drive is below that 10th percentile. Above the threshold, the municipality is classified with high accessibility.

The previous two steps identify three types of municipalities:

In order to account for unique characteristics of municipalities, the methodology differentiates those municipalities inside FUAs and outside FUAs by size of population. The municipalities outside FUAs with low accessibility are not differentiated by size of population given their relatively homogenous distribution in size. Therefore the final step to classify municipalities by size of population is as follows:

3. Dividing municipalities with high accessibility outside FUAs and municipalities inside FUAs by population size. The methodology identifies municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility and municipalities inside FUAs that are relatively large and small in terms of population. To define the population threshold, the methodology follows Poland’s population distribution of all municipalities and Poland’s official threshold to differentiate among small and medium/large cities (20 000 inhabitants). Therefore, municipalities with a population of more than 20 000 inhabitants are classified as big and those with a population of fewer than 20 000 inhabitants as small.

The previous three steps identify five subtypes of municipalities:

These five subtypes of municipalities introduce a new lens to look at municipalities in Poland by differentiating among municipalities inside and outside FUAs, large or small in terms of population and high or low level of accessibility to population settlements. This classification brings a number of policy advantages:

1. Enabling to identify and group municipalities based on measurable characteristics. Shifting from administrative, political and historic classification (see Chapter 6 for further discussion) to one based on economic functionality, size and accessibility.

2. Identifying different types of rural municipalities in the territory (close to and far from FUAs).

3. Allowing identification of common challenges and opportunities across groups of municipalities of certain type, which can lead to common policy approaches and cross-learning mechanisms from the peers among relevant types of municipalities.

According to this alternative OECD classification, most of Poland’s population lives inside FUAs (56%). Particularly, big municipalities in FUAs concentrate the majority of Poland’s population (41.6%) within a small number of municipal units (6% of total municipalities). The second-largest subtype in terms of population are small municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility (out FUA with high access), which host 23.7% of the population in 49% of Poland’s municipalities. Figure 0.3 describes the geographical distribution of municipalities in each of the five types.

References

[9] Assembly of European Regions (2017), “Regionalisation in Poland: Modifying territorialisation while acknowledging different regional identities”, https://aer.eu/regionalisation-poland-modifying-territorialisation-acknowledging-different-regional-identities-ror2017/#:~:text=The%20important%20law%20on%20local,by%20a%20transfer%20of%20funds.

[8] Baro Riba, D. and P. Mangin (2019), Local and Regional Democracy in Poland, Council of Europe, https://rm.coe.int/local-and-regional-democracy-in-poland-monitoring-committee-rapporteur/1680939003.

[19] Fadic, M. et al. (2019), “Classifying small (TL3) regions based on metropolitan population, low density and remoteness”, OECD Regional Development Working Papers, No. 2019/06, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b902cc00-en.

[1] Government of Poland (2017), Strategy for Responsible Development for the Period up to 2020, https://www.gov.pl/documents/33377/436740/SOR_2017_streszczenie_en.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2021).

[12] Government of Poland (2009), Act of 23 January 2009 on Voivodeship and Governmental Administration in Voivodeship, https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20090310206 (accessed on 29 March 2021).

[10] OECD (2020), Decentralisation and Regionalisation in Portugal: What Reform Scenarios?, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/fea62108-en.

[17] OECD (2020), “Metropolitan areas”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00531-en.

[13] OECD (2020), OECD Database on Regional Government Finance and Investment: Key Findings, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/datacollectionandanalysis.htm.

[18] OECD (2020), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/959d5ba0-en.

[16] OECD (2020), “Regional demography”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/a8f15243-en.

[21] OECD (2020), Rural Well-being: Geography of Opportunities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d25cef80-en.

[26] OECD (2020), Rural Well-being: Geography of Opportunities, OECD Rural Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d25cef80-en.

[2] OECD (2018), OECD Rural Policy Reviews: Poland 2018, OECD Rural Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264289925-en.

[7] OECD (2016), Better Policies Series Brochure on Poland.

[5] OECD (2016), Governance of Land Use in Poland: The Case of Lodz, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260597-en.

[3] OECD (2013), Poland: Implementing Strategic-State Capability, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201811-en.

[4] OECD (2011), OECD Urban Policy Reviews, Poland 2011, OECD Urban Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264097834-en.

[6] OECD (2008), Territorial Review of Poland, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/oecdterritorialreviewspoland.htm (accessed on 20 May 2021).

[22] OECD/EC (2020), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d0efcbda-en.

[23] OECD/European Commission (2020), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d0efcbda-en.

[24] OECD/European Commission (2020), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d0efcbda-en.

[25] OECD/European Commission (2020), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d0efcbda-en.

[15] OECD/European Commission (2020), Cities in the World: A New Perspective on Urbanisation, OECD Urban Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/d0efcbda-en.

[14] Statistics Poland (2020), Classification of Territorial Units, https://stat.gov.pl/en/regional-statistics/classification-of-territorial-units/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

[20] Statistics Poland (2020), Regional Statistics, https://stat.gov.pl/en/regional-statistics/ (accessed on 15 November 2020).

[11] Sześciło, Dawid and Kulesza, Michał (2012), “Local government in Poland”, in Moreno, A. (ed.), Local Government in the Member States of the European Union: A Comparative Legal Perspective, INAP, Madrid.

The OECD has adopted a new typology to classify administrative TL3 regions based on the presence and access to FUAs (OECD, 2020[21]). The OECD typology classifies TL3 regions into two groups, metropolitan and non-metropolitan regions. Within these two groups, five different types of TL3 regions are identified. Annex Table 1.A.1 depicts the classification of TL3 regions in Poland according with this typology:

Notes

← 1. The newest form of territorial structure (still of a pilot character in Poland) is the metropolitan association, established in 2017 by virtue of the Metropolitan Associations Act in the Silesian Voivodeship and dedicated only to that territory in Poland. According to the Act, the association of municipalities within the Silesian Voivodeship is characterised by strong functional bounds and advanced urbanisation processes, located in an area coherent in spatial terms and inhabited by at least 2 000 000 residents.

← 2. Please note that due to lack of equivalents and to ensure comprehensibility for a broad audience in Poland, the Polish language version of the report includes analogous translations of certain terms. For example, the Polish version of this report translates “non-metropolitan regions” to a Polish term closely related to the term “rural areas". An explanation of each of the relevant terms can be found in the glossary of the report.