copy the linklink copied!Impact of childcare breaks on pension entitlements

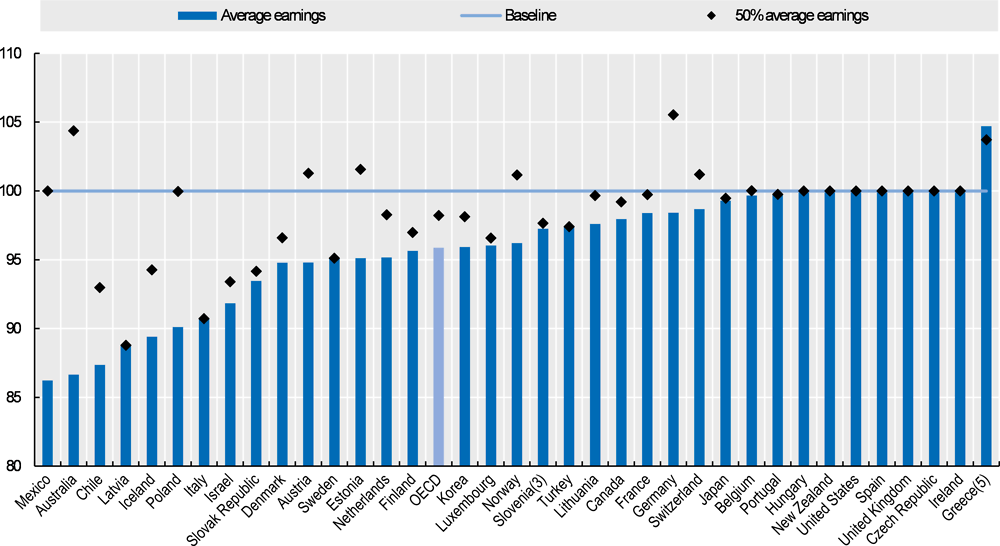

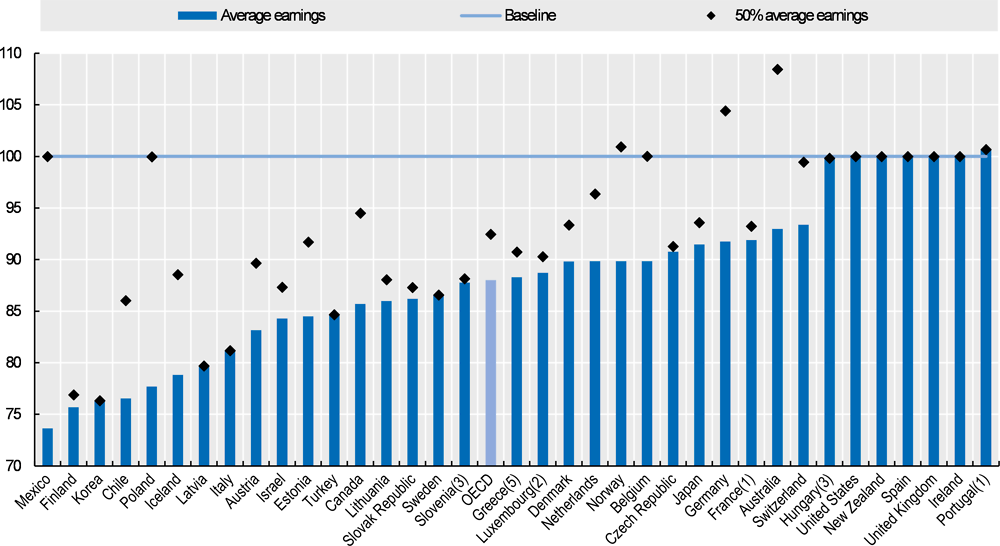

The analysis above has concentrated on showing full-career replacement rates where there has been no period of absence from the labour market. This future gross replacement rate shows the level of pension benefits in retirement from mandatory pension schemes relative to earnings when working. However, many individuals will have an interrupted career because of having children and this indicator shows how this will affect future pension entitlements. Women with average earnings and taking five years out of the labour market to care for children will have a pension equal to 96% of that for a full-career female worker on average across the 36 OECD countries with substantial cross-country variation. At the top of the range, Greece offers benefits 5% higher than for the full-career worker, but getting a full pension requires retiring five years later, whilst at the bottom of the range Mexico has a future benefit at 86% of the full-career worker.

All OECD countries, with the exception of the United States offers credit for periods of maternity, but the analysis presented here covers the period beyond maternity leave, looking specifically at childcare periods. Most OECD countries aim to protect periods of absence from the labour market to care for children. Whilst fathers are becoming increasingly able to access periods of credit the mother is still the primary recipient in many countries and so this analysis has been computed for females only.

Credits for childcare typically cover career breaks until children reach a certain age. They are generally less generous for longer breaks and for older children. Many OECD countries credit time spent caring for very young children (usually up to 3 or 4 years old) as insured periods and consider it as paid employment. By contrast, extended periods of leave to raise older children (usually aged between 6 and 16) are typically taken into account only to determine eligibility for early retirement and the minimum pension. Some countries (the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary and Luxembourg) factor childcare into assessments of eligibility, but disregard them when computing the earnings base.

The gross pension entitlements of mothers who take time out of employment is illustrated in Figures 5.10 and 5.11 at different earnings levels for breaks from work of five and ten years, respectively. In Greece the benefits are higher with a five-year career break for childcare though these individuals will retire five years later to get a full pension; they only have higher benefits because those in payment for the full-career worker are indexed to prices. In the Czech Republic, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States, pensions are not affected by breaks whatever the earnings. In Ireland the reason is that career breaks to care for children under 12 are considered insured periods up to a maximum of 20 years. Those breaks are therefore excluded from the averaging periods used to compute pension entitlements. In Spain, too, the five years that mothers may spend looking after their children count as insured periods. In New Zealand, the public pension is simply residence-based, so any period spent out of the labour market does not change the benefits.

In Germany having a child gives one parent a credit of one pension point for three years, thereby making it equivalent for pension purposes to earning the average wage throughout the credit period resulting in a much higher benefit entitlement for low earners. Similarly in Estonia credits are given based on the nationwide average income again resulting in higher benefits for low earners.

In Austria, Chile, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania and Mexico, contribution gaps can make a substantial dent in retirement income, especially if the childcare period lengthens. In some of these countries crediting mechanisms for childcare do not exist (such as in Iceland, Israel and Mexico). In the other countries where they do exist they better cover short interruptions and/or low-earners.

In six countries, Greece and Slovenia for both 5- and 10-year breaks and France, Hungary, Luxembourg and Portugal for the 10-year break, workers have to retire later to be entitled to a pension without penalty due the rules governing required contribution periods. In Slovenia, for example, a worker who enters paid employment at 22 but takes ten years out of work will have contributed for less than 40 years at age 62, and will therefore have to work until 65 to be able to retire without penalty.

Definition and measurement

The OECD baseline full-career simulation model assumes labour market entry at the age of 22. For the childcare career case, women are assumed to embark on their careers as full-time employees at 22, and to stop working during a break of up to ten years from age 30 to care for their two children born when the mother was aged 30 and 32; they are then assumed to resume full-time work until normal retirement age, which may increase because of the career break. Any increase in retirement age is shown in brackets after the country name on the charts, with the corresponding benefits for the full career worker indexed until this age. The simulations are based on parameters and rules set out in the online “Country Profiles” available at http://oe.cd/pag.

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/b6d3dcfc-en

© OECD 2019

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.