Chapter 5. Applying an internal control and risk management framework that safeguards public integrity in Argentina

This chapter assesses Argentina’s internal control and risk management framework against international models and good practices from OECD member and non-member countries. It provides an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of the internal control and risk management framework in Argentina and proposals for how this framework could be reinforced, such as through implementing a strategic approach to risk management that incorporates integrity risks, establishing control committees in all government entities, and strengthening the mandate and independence of the external audit function.

5.1. Introduction

An effective internal control and risk management framework is essential in public sector administration to safeguard public integrity, enable effective accountability and preventing corruption. Such a system should include:

-

a control environment with clear objectives that demonstrate managers’ commitment to public integrity and public service values, and that provides a reasonable level of assurance of an organisation’s efficiency, performance and compliance with laws and practices;

-

a strategic approach to risk management that includes assessing risks to public integrity, addressing control weaknesses, as well as building an efficient monitoring and quality assurance mechanism for the risk management system; and

-

control mechanisms that are coherent and include clear procedures for responding to credible suspicions of violations of laws and regulations and facilitating reporting to the competent authorities without fear of reprisal (OECD, 2017[1]).

In addition to an effective internal control and risk management environment, a public administration system should have:

-

an internal audit function that is effective and clearly separated from operations; and

-

a supreme audit institution that has a clear mandate and is independent, transparent and effective (OECD, 2017[1]).

5.2. Establishing a control environment with clear objectives

5.2.1. SIGEN could ensure that clear objectives for the control environment are communicated to staff across the national public sector

Before assessing risks and determining internal control activities, it is vital that an entity establishes clear objectives for the entity as a whole, for individual programmes and for the control environment. Where there is no clear objective, internal controls and risk management cannot be effectively implemented.

According to SIGEN, projects must align with the National Government’s 100 priority initiatives (which are grouped into eight strategic objectives). In addition, there are plans to establish a Control Board within the scope of the Chief of Cabinet of Ministers (JGM), which will monitor these projects. The National Budget Office (ONP), also provides direct technical assistance, in order to help link strategic planning to the national budget.

Through its General Internal Control Standards for the National Public Sector, SIGEN outlines that entities should clearly define the way in which each area contributes to the achievement of the entity’s objectives (SIGEN, 2014, p. 20[2]). However, interviews during the OECD’s October 2017 mission to Argentina indicated that, within the public administration, there is little awareness of these standards and that these standards are not being consistently applied. It is unclear whether entities have defined their objectives and the way in which each area contributes to this objective.

The control environment is the foundation for all components of internal control. According to the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions’ (INTOSAI’s) Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector, elements of the control environment include: organisational structure; and “tone at the top” (i.e., management’s philosophy and operating style); and a supportive attitude toward internal control throughout the organisation (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 17[3]) (see also chapter 3).

In Argentina, SIGEN is the Office of the Comptroller General and the entity responsible for coordinating the internal audit units and establishing standards of internal control. According to Article 97 of the National Financial Administration and Public Sector Control Systems Act—Law No. 24.156 (Financial Administration Act), SIGEN is an "entity with its own legal status and administrative and financial autarchy dependent on the National Executive Power". According to Articles 100, 101 and 102, the internal control system is made up of SIGEN and the internal audit units in each entity. Under the law, units are created in each jurisdiction and in the entities that depend on the National Executive Power. These units depend hierarchically on the authority of each entity, but are coordinated by SIGEN. The superior authority of each entity is ultimately responsible for the implementation of an adequate system of internal control.

Regarding SIGEN’s technical coordination of the Internal Audit Units, SIGEN provided information in April 2018 that the powers granted under Decree No. 72/2018, such as the designation or removal of the Internal Auditor, has increased the institutional strength and independence of internal audit units.

Article 103 of the Act stipulates that the internal control model must be comprehensive and integrated and must be based on the criteria of economy, efficiency and effectiveness. Article 104 outlines SIGEN’s functions—which includes supervising “the proper functioning of the internal control system”, and the responsibility for the internal audit system. (Argentina, 2016[4]).

Argentina established Internal Control standards in 1998, basing them on the first version of the COSO framework. The most recent version, General Internal Control Standards for the National Public Sector, was published in 2014 (SIGEN, 2014[2]). These standards were designed to help implement the internal control system that is set out in the Financial Administration Act. Although the standards themselves are strong, the implementation of them is not. As mentioned, the OECD found during its October 2017 mission that there was a lack of awareness of these standards in the public administration. Further information provided by SIGEN in April 2018 indicated that they disseminated the standards in 2015 and provided a number of training courses for the 190 Internal Audit Units (UAI) between 2015 and 2017. Courses included:

-

Audit 1, 2 and 3: for improving the control and audit processes, as well as increasing, strengthening and updating knowledge in this area;

-

Control tools and Intermediate and Advanced Audit: for mastering procedures and control techniques and strengthening knowledge of internal audit and control and internal audit supervision;

-

Risk Assessment: for improving risk assessment and identifying applicable methodologies; and

-

Planning of an audit: for improving the planning and control processes, the elaboration of standards, and the dissemination of control regulations.

SIGEN could coordinate with human resources units to incorporate key internal control and risk management requirements into mandatory training and induction sessions for operational staff, in addition to auditors. Government entities could also work to embed internal control standards in the daily work of the public service—incorporating them into standard operating procedures and outlining concrete actions that need to be undertaken by operational staff in their everyday work and for their specific positions. Measures could include:

-

introducing awareness programs on the need for internal control and on the roles of each area and staff member; and

-

induction training for all staff, including senior management and managers on the internal control system

SIGEN indicated in April 2018 that they agreed that new dissemination and awareness strategies would be valuable.

5.2.2. SIGEN could assist government entities to more consistently apply the principles of the three-lines-of-defence model to give greater responsibility for internal control and risk management to operational management

While senior managers should be primarily responsible for managing risk, implementing internal control activities and demonstrating the entity’s commitment to ethical values, all officials in a public organisation—from the most senior to the most junior—should play a role in identifying risks and deficiencies and ensuring that internal controls address and mitigate these risks.

One of the core missions of public officials responsible for internal control is to help ensure that the organisation’s ethical values, and the processes and procedures underpinning those values, are communicated, maintained and enforced throughout the organisation.

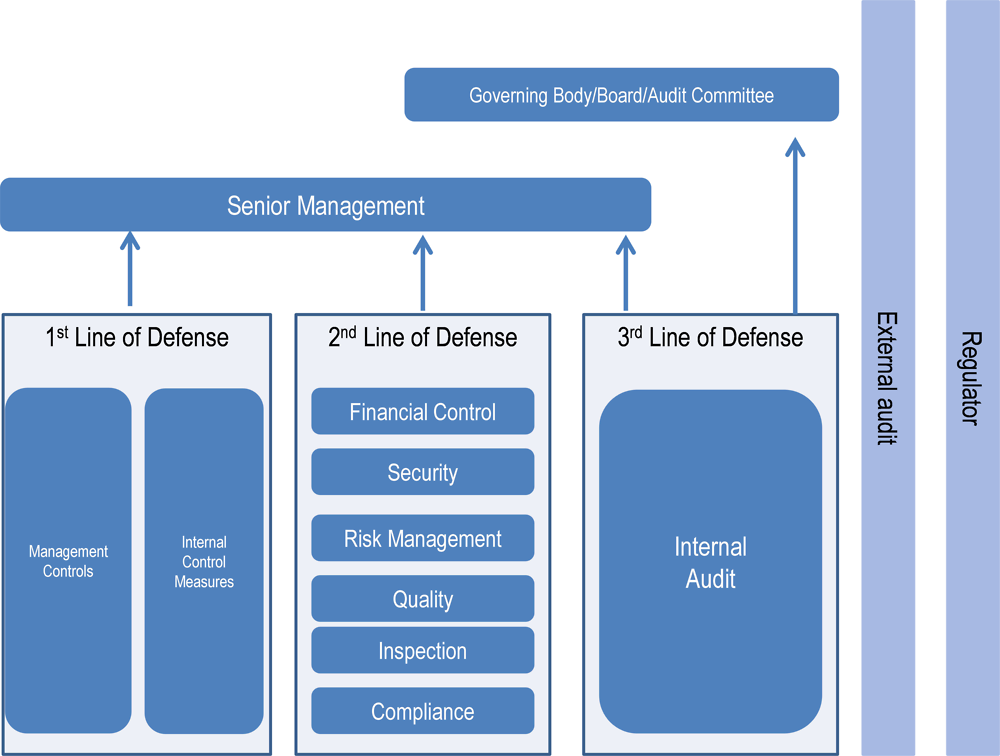

Indeed, the leading fraud and corruption risk management models among OECD member and partner countries underscore that the primary responsibility for preventing and detecting corruption rests with the staff and management of public entities. Such corruption risk management models often share similarities with the Institute of Internal Auditor’s (IIA) Three Lines of Defence Model (see Figure 5.1).

According to the IIA, the first line of defence comprises operational management and personnel. Those on the frontline naturally serve as the first line of defence because they are responsible for maintaining effective internal controls and for executing risk and control procedures on a day-to-day basis. Operational management identifies, assesses, controls, and mitigates risks, guiding the development and implementation of internal policies and procedures and ensuring that activities are consistent with goals and objectives (Institute of Internal Auditors, 2013[5]). According to information provided by SIGEN in April 2018, SIGEN has been working for a number of years to establish the first line of defence—establishing tools to generate awareness and to modify behaviours and working to transform the public administration over time. SIGEN indicates that they have incorporated the three lines of defence model into their control system, but acknowledges that they have further to go before reaching their optimum point.

The second line of defence includes the next level of management—those with responsibility for the oversight of delivery. This line is responsible for establishing a risk management framework, monitoring, identifying emerging risks, and regular reporting to senior executives. Operational management in Argentina’s government entities could be given greater responsibility for the implementation and oversight of internal control and risk management activities. Operational management should regularly report to senior management and be held accountable for the implementation of internal control activities.

The third line of defence is the internal audit function. Its main role is to provide senior management with independent, objective assurance over the first and second lines of defence arrangements (Institute of Internal Auditors, 2013[5]).

According to SIGEN, their internal audit units, as the third line of defence, issue reports on:

-

special audits;

-

internal audit unit supervision;

-

evaluation of the internal control system; and

-

regulatory compliance control—such as, year-end reports, budget evaluation, subsidies and transfers, contract management, and verification of the purchasing and contracting process.

Further, Decree No. 1344/2007 established that higher authorities must request a prior opinion from the Internal Audit Unit for the approval and modification of regulations and procedural manuals, which “must incorporate suitable instruments for the exercise of control”. To guide this work, SIGEN issued the "Guidelines for intervention by the Internal Audit Units in the approval of regulations and procedural manuals" in 2014 (Resolution SIGEN No. 162/2014).

Article 102 of Argentina’s Financial Administration Act establishes that “the functions and activities of internal auditors must be kept separate from the operations subject to their examination". Interviews during the OECD Mission to Buenos Aires in October 2017 indicated that some officials did not have a clear understanding of the three lines of defence model or the importance of separation, with some operational staff stating that the Internal Audit function should bear full responsibility for internal control.

SIGEN should assist government entities, building on already existing training and awareness activities, to help ensure that staff understand and consistently apply the internationally recognised three lines of defence model across the public sector.

5.3. Developing a strategic approach to risk management

5.3.1. SIGEN could improve its risk management approach to ensure it is consistent and clearly separated from the internal audit function

An effective internal control and risk management framework includes policies, structures, processes and tools that enable an organisation to identify and appropriately respond to risks. SIGEN’s Principle 7 of Internal Control states that each entity should identify, analyse, and manage risks that can affect the achievement of the entity’s objectives, which aligns with good governance practices among OECD countries. However, the OECD found through interviews, that operational risk management was generally not being undertaken by operational management and that SIGEN’s standards related to risk management were not being applied at the operational level.

SIGEN’s 2017 Annual Plan outlined, among its strategic objectives, that it would design and maintain a risk management system. During mission interviews, SIGEN internal audit representatives indicated that they were currently piloting a new risk management methodology with one entity (which included an evaluation carried out jointly between the internal audit unit and the entity, as well as a separate evaluation carried out by SIGEN). SIGEN indicated that they intended to move from the pilot to general implementation—however, they were expecting some difficulties with getting engagement from entities. This will particularly be the case if entity management sees it as an audit tool to be used by auditors to identify and expose entity failings.

SIGEN issues an annual Risk Map of the National Public Sector, which is made up of a matrix that exposes the levels of risk associated with the functions of government for each agency or entity of the National Public Sector. This document assists with audit planning and has been issued since 2005. Further, according to SIGEN, 2018 guidelines for internal audit planning established the obligation to incorporate actions to induce the superior authority of the entity to draw up a risk matrix. Internal Auditors developed a risk analysis and management methodology that included a self-evaluation form for the superior authority and each area of the organisation.

SIGEN could consider improving its risk management framework to be more strategic, consistent, operational, and clearly separated from the audit function. Operational managers should be able to undertake risk assessments without the fear of reprisal and completely separate from risk assessment undertaken by auditors in their audit planning. Auditors should, of course, have access to risk management information during an audit, but managers should have the freedom to manage their risks in an operational way that is frank and that exposes the real issues. Managers will not have this liberty if auditors are the ones setting up the risk management framework and having operational management create risk management information for the specific use of audit planning. There would be a conflict in this instance. To be effective, the real purpose of the risk management tool needs to be considered. Auditors should, indeed have access to all governance information, including risk management information and should continue to conduct their own separate risk analyses during their audit planning. However, operational management should be undertaking their own risk assessments for use operationally—not in conjunction with auditors or at the behest of the auditors.

Internal auditors could drive change by including audits in their audit work programmes on how risks are being managed and drawing attention to the lack of operational risk management across government in their audit reports.

In the Canadian government, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat has a range of branches and responsibilities, including internal audit coordination under the Office of the Comptroller General and the development of the Risk Management Framework under the Priorities and Planning Unit, as outlined in Box 5.1. These functions are clearly separated to avoid a conflict of interest. Auditors should not design frameworks, create guidance or set standards on risk management, as they are responsible for auditing the risk management system.

The Treasury Board of Canada is responsible for accountability and ethics, financial, personnel and administrative management, comptrollership, and approving regulations. The President of the Treasury Board: translates the policies and programs approved by Cabinet into operational reality; and provides departments with the resources and the administrative environment they need to do their work. The Treasury Board has an administrative arm, the Secretariat, which was part of the Department of Finance until 1966.

As the administrative arm of the Treasury Board, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat has a dual mandate: to support the Treasury Board and to fulfil the statutory responsibilities of a central government agency. The Secretariat is tasked with providing advice and support to Treasury Board ministers in their role of ensuring value-for-money as well as providing oversight of the financial management functions in departments and agencies. The Secretariat is also responsible for the comptrollership function of government and the development for key policy and guidance activities. The functions of the Comptroller General and the coordination of Internal Audit are clearly separated from the function of developing risk management guidelines:

-

The Internal Audit Sector of the Office of the Comptroller General of Canada is responsible for the health of the federal government internal audit community. It provides independent assurance on governance, risk management and control processes and leads the audit community in implementing the Treasury Board Policy on Internal Audit (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2017[6]).

-

The Priorities and Planning Unit is responsible for key policy and planning activities that underpin both government-wide management excellence and efficient and effective corporate governance within the Secretariat. This unit provides leadership for governance and planning processes to ensure coherence in corporate priorities, clear accountabilities, and continuous improvement. This includes the Risk Management Framework (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2017[7]).

Source: (Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, 2018[8]).

5.3.2. SIGEN could promote the incorporation of risk management into the culture of government entities by providing clear guidance for operational staff and including risk management requirements in mandatory training

Once a clear risk management framework has been established, risk management should be promoted and communicated and should permeate the organisation’s culture and activities in such a way that it becomes the business of everyone within the organisation—it should not be the domain of the internal audit units and should not be managed in isolation. Informed employees who can recognise and deal with risks are more likely to identify situations that can undermine the achievement of institutional objectives. Operational risk management begins with establishing the context and setting an organisation’s objectives. This concept is captured in SIGEN’s Principle 6 of Internal Control, which states that an Organisation ‘must specify objectives with clarity’ (SIGEN, 2014, p. 23[2]). Risk management continues with the identification of events that might have a negative impact on their achievement and represent risks.

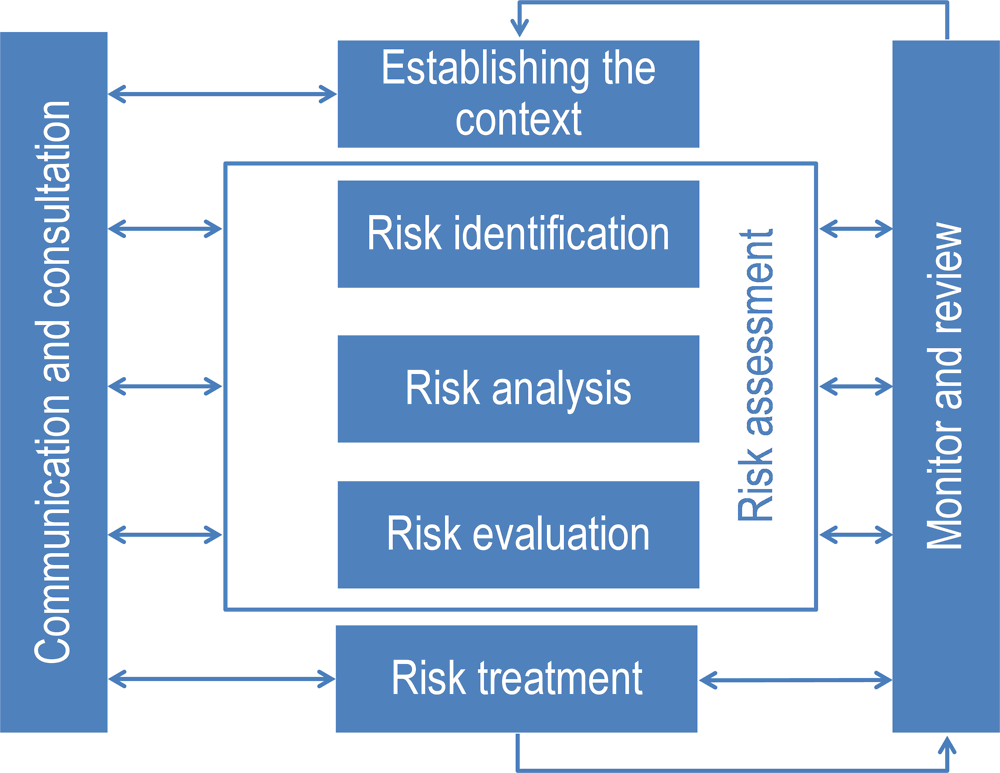

SIGEN outlines a risk assessment model under its Principle 7 of Internal Control, which includes risk identification, analysis and evaluation, in alignment with international risk management standards (SIGEN, 2014, pp. 25–26[2]). According to the ISO standards for risk management, risk assessment is a three-step process that starts with risk identification and is followed by risk analysis, which involves developing an understanding of each risk, its consequences, the likelihood of those consequences occurring, and the risk’s severity. The third step is risk evaluation, which involves determining the tolerability of each risk and whether the risk should be accepted or treated. Risk treatment is the process of adjusting existing internal controls or developing and implementing new controls to bring a risk’s severity to a tolerable level (ISO, 2009[9]). A depiction of the risk management cycle is provided at Figure 5.2.

SIGEN’s General Internal Control Standards outline a solid risk management framework; however, it does not clearly state what risk information should be collected or how responsibility for risk will be assigned. Further, the OECD found through interviews with government officials that although auditors undertake an annual risk mapping exercise, these standards were not consistently applied at the operational level.

Appropriate and reliable risk information is essential to operationalising a risk management framework. Information to support risk management can come from a number of internal and external sources. Further, a consistent approach to sourcing, recording, and storing risk information improves the reliability and accuracy of required information. Staff should be made aware of the risk management framework and key requirements through training and awareness-raising activities. Communication and consultation with staff is also a key step towards securing input into the risk management process and giving staff ownership of the outputs of risk management. The Australian Government has developed guidance on building risk management capability in entities (outlined in Box 5.2), which could provide some useful insights.

The Australian Department of Finance has developed guidance on how to build risk management capability in government entities, focused on the following areas:

People capability – A consistent and effective approach to risk management is a result of well skilled, trained and adequately resourced staff. All staff have a role to play in the management of risk. Therefore, it is important that staff at all levels of the entity have clearly articulated and well communicated roles and responsibilities, access to relevant and up-to-date risk information, and the opportunity to build competency. Building the risk capability of staff is an ongoing process. With the right information and learning and development, an entity can build a risk aware culture among its staff and improve the understanding and management of risk across the entity. Considerations include:

-

Are risk roles and responsibilities explicitly detailed in job descriptions?

-

Have you determined the current risk management competency levels and completed a needs analysis to identify learning needs?

-

Do induction programmes incorporate an introduction to risk management?

-

Is there a learning and development programme that incorporates ongoing risk management training tailored to different roles and levels of the entity?

Risk systems and tools – Risk systems and tools provide storage and accessibility of risk information. The complexity of risk systems and tools often range from simple spreadsheets to complex risk management software. The availability of data for monitoring, risk registers, and reporting will assist in building risk capability. Considerations include:

-

Are your current risk management tools and systems effective in storing the required data to make informed business decisions?

-

How effective are your risk systems in providing timely and accurate information for communication to stakeholders?

Managing risk information – Successfully assessing, monitoring and treating risks across the entity depends on the quality, accuracy and availability of risk information. Considerations include:

-

Have you identified the data sources that will provide the required information to have a complete view of risk across the entity?

-

What is the frequency of collating risk information?

-

Do you have readily available risk information accessible to all staff?

-

How would you rate the integrity and accuracy of the available data?

Risk management processes – The effective documentation and communication of risk management processes will allow for clear, concise and frequent presentation of risk information to support decision-making. Considerations include:

-

Are your risk management processes well documented and available to all staff?

-

Do your risk management processes align to your risk management framework?

-

Is there training available, tailored to different audiences, in the use of your risk processes?

Source: (Department of Finance, 2016[10]).

5.3.3. Argentinian government entities could operationalise the risk management framework by assigning clear responsibility for risk management to senior managers

Managers should be responsible for the design, implementation, and monitoring of the internal control and risk management functions, with this being recognised in laws and policies of many countries. Having laws that ensure managers’ ownership over these activities can provide incentives for managers, and aid countries in achieving committed oversight and stronger accountability. In the majority of OECD countries, managers in the executive branch are held responsible by law for monitoring and implementing control and risk management activities. Moreover, many countries have laws that hold managers specifically responsible for integrity risk management policies, as depicted in Table 5.1. However, in Argentina line managers have not been given responsibility for internal control or risk management (OECD, 2017, p. 158[11]).

Responsibility for specific risks, including fraud and corruption risks needs to be clearly assigned to the appropriate senior managers. These managers need to take ownership of the risks that could affect their objectives, use risk information to inform decision-making and actively monitor and manage their assigned risks. These managers should also be held accountable to the executive through regular reporting on risk management – (Department of Finance, 2016[10]).

5.4. Implementing coherent internal control mechanisms

5.4.1. SIGEN could assist government entities to strengthen their internal control mechanisms to ensure that they are implemented and effective and that reasonable assurance is provided

One fundamental way risks are mitigated is through internal control mechanisms. Internal control mechanisms are implemented by an entity’s management and personnel and continuously adapted and refined to address changes to the entity’s environment and risks. Argentina’s General Internal Control Standards define internal control as:

A process carried out by higher authorities and the rest of the entity’s personnel, designed to provide a degree of reasonable safety in terms of the achievement of organisational objectives – both in relation to the operational management, the generation of information and compliance with regulations (SIGEN, 2014, p. 8[2]).

This aligns with INTOSAI’s definition, which views internal control as activities designed to address risks that may affect the achievement of the entity’s objectives and to provide reasonable assurance that the entity’s: operations are ethical, economical, efficient and effective; accountability and transparency obligations are met; activities and actions are compliant with applicable laws and regulations; and resources are safeguarded against loss, misuse, corruption and damage (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 6[12]).

Internal control activities should not attempt to provide absolute assurance – as this could constrict activities to a point of severe inefficiency. ‘Reasonable assurance’ is a term often used in audit and internal control environments. It means a satisfactory level of confidence given due consideration of costs, benefits and risks. Argentina’s internal control standards include the concept of reasonable assurance, stating that “an effective internal control system provides reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of the objectives of the organisation” (SIGEN, 2014, p. 9[2]).

Determining how much assurance is reasonable requires judgment. In exercising this judgment, managers should identify the risks inherent in their operations and the levels of risk they are willing to tolerate under various circumstances. Reasonable assurance accepts that there is some uncertainty and that full confidence is limited by the following realities: human judgment in decision-making can be faulty; breakdowns can occur because of simple mistakes; controls can be circumvented by collusion of two or more people; and management can choose to override the internal control system.

Argentina’s standards outline three considerations that should be taken into account when internal control mechanisms are designed:

-

Integrity: ensuring integrity during the treatment, processing and registration of all transactions or operations;

-

Accuracy: ensuring operations are timely and correct; and

-

Validity: ensuring posted transactions accurately represent executed operations (SIGEN, 2014, p. 30[2]).

These are valid considerations that could assist Argentina government entities with establishing more effective internal control activities. Further, it is not enough to have standards and controls in place; they need to be implemented and effective. It has been observed that a characteristic feature of the Argentine government is ‘not the lack of control, but the fiction of control’ and that ‘while the law is complied with formally, it is not complied with substantially (Santiso, 2009, p. 86[13]). Further, this ‘façade formalism’ constrains managers by detecting minor administrative mistakes rather than addressing structural dysfunctions and political corruption (Santiso, 2009, p. 86[13]). To provide reasonable assurance on an entity’s operations, it is vital that internal control and its underlying principles are fully integrated.

Argentina’s standards for internal control include a section on “control activities”, which outlines and defines general controls, IT controls and relevant policies and procedures. According to Argentina’s standards, control activities should be aimed at reducing the risks that can affect the achievement of the objectives of the organisation, are both preventive and detective, and carried out by all areas of an entity (SIGEN, 2014, p. 29[2]). This corresponds well with INTOSAI’s Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector, which states that internal control activities should occur throughout an entity, at all levels and in all functions and that internal controls should include a range of detective and preventive control activities. However, as noted in the previous sections, SIGEN’s standards are not being systemically applied.

In particular, interviews during the OECD’s October 2017 mission indicated that internal audits frequently find issues with the use of petty cash and expenditure on travel – related to mismanagement, inefficiency and corruption. In addition to internal auditors examining the internal control system and identifying areas for improvement, government entities could consider updating its internal controls related to petty cash and travel and improving or introducing controls where there are identified gaps. For example, authorising and executing procurement transactions should only be done by persons with appropriate authority. Authorisation is the principal means of ensuring that only valid transactions and events are initiated as intended by management. Authorisation procedures, which should be documented and clearly communicated to managers and employees, should include the specific conditions and terms under which authorisations are to be made. Conforming to the terms of an authorisation means that employees act in accordance with directives and within the limitations established by management or legislation (INTOSAI, 2010, p. 29[12]).

SIGEN provided further information to the OECD in April 2018 that it has worked to strengthen the internal control system since its creation in 1992. SIGEN sees this as a long-term process and initially aimed its efforts at determining the status of the system, establishing internal audit units, and developing the regulatory framework. Subsequently, SIGEN has designed monitoring tools and methodologies to assist entities, such as the Program for Strengthening the Internal Control System, which includes the Commitment Plan to Improve Management and Internal Control, the Particular Rules for the Establishment and Operation of Control Committees, and the Self-Assessment and Diagnosis Methodology of Processes.

5.5. Improving the internal audit function

5.5.1. SIGEN could ensure that its central coordination of internal audit leverages the available resources in order to strengthen oversight and enable a cohesive response to integrity risks

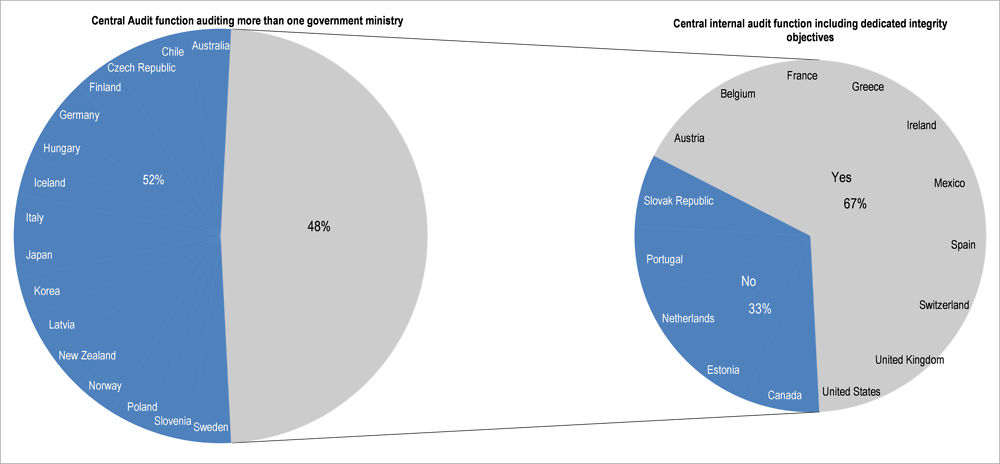

Having a central internal audit function, particularly that includes integrity in its strategic objectives, can strengthen the coherence and harmonisation of the government’s response to integrity risks. Auditing of multiple entities at a central level can: leverage available audit resources; enhance the government’s ability to identify systemic, cross-cutting issues; and put measures in place to respond from a whole-of-government perspective (OECD, 2017[11]). Many OECD countries have a central internal audit function that has responsibilities for auditing more than one government ministry – and most of these central internal audit functions have dedicated integrity objectives, as shown in Figure 5.3.

Argentina has a centrally coordinated internal audit function, an annual audit risk map, and guidelines for internal audit planning, but it could build on this to enhance oversight by establishing dedicated strategic integrity objectives and by identifying trends and systemic issues and giving management the ability to respond to integrity risks, in a cohesive and holistic way. The United Kingdom’s Government Internal Audit Agency is a good example of an internal audit entity that has dedicated integrity objectives, as outlined in Box 5.3.

The Government Internal Audit Agency (GIAA) helps ensure the United Kingdom government and the wider public sector provide services and manages public money effectively and develops better governance, risk management and internal controls. The GIAA delivers a risk-based programme of work culminating in an annual report and opinion on the adequacy and effectiveness of government organisations’ frameworks of governance, risk management and internal control. It provides a range of services, including:

-

Assurance work: This provides an independent and objective evaluation of management activities in order to give a view on an organisation’s effectiveness in relation to governance, risk management and internal controls.

-

Counter fraud and investigation work: We provide advice and support to customers on counter fraud strategies, fraud risk assessments, and measures to prevent, deter and detect fraud. Where commissioned, their professionally trained staff investigate suspicions of internal or supplier fraud or malpractice.

Source: (United Kingdom Government Internal Audit Agency, 2018[14]).

5.5.2. All Argentinian government entities could implement control committees to better monitor the implementation of audit recommendations

SIGEN’s Internal Audit Standards state that auditors must outline recommendations of possible steps to correct detected shortcomings as outlined in audit observations, with these recommendations seeking to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the entity and its internal control mechanisms. The Standards further state that formal recommendations will “provide a basis for the subsequent follow-up on the part of the internal audit unit, the SIGEN or others” (SIGEN, 2002, p. 26[15]).

According to SIGEN, it requires the follow-up of observations through Resolution SIGEN N ° 15/2006 and Resolution SIGEN N ° 73/2010. Further, through the recent Decree No. 72/2018, it is necessary to follow up through the Control/Audit Committee with the participation and commitment of the superior authority.

The Standards also state that auditors must monitor compliance with the instructions given by the entity authorities for solving the shortcomings exposed in audit reports. This must be verified through follow-up audits. To this end, SIGEN expects that databases be maintained, containing all the observations and recommendations made in connection with the work. SIGEN expects that periodic monitoring will enable the auditor to ensure that appropriate action is taken and to determine areas for the conduct of new audits. Further, monitoring can assist auditors with evaluating not only the correctness of their advice, but also if the results obtained from their recommendations correspond with expectations. (SIGEN, 2002, p. 32[15]).

According to SIGEN’s 2017 Annual Plan, of the 53 process controls activities planned to be undertaken in 2017, three were to relate to the follow-up of audit recommendations:

-

Follow-up on pending comments and recommendations in audit reports related to non-contributory pensions (Ministry of Social Development);

-

Follow-up on the Report executed by the Internal Audit Unit of the Posadas National Hospital; and

-

Follow-up on the Report executed by the Internal Audit Unit of the National Hospital Network Specialized in Mental Health and Addiction (SIGEN, 2017, pp. 100–104[16]).

According to SIGEN, it records and regularly follows up internal audit observations and recommendations. In 2001, SIGEN dictated (through Circular No. 1, 17 January 2001) that all Internal Audit Units under its jurisdiction had to present the details of the audit observations pending regularisation at the close of fiscal year (using the SISIO System). In 2006, the Annual Plans of the Internal Audit Units were integrated into the SISIO system, which provided an online platform for including follow-up in the internal audit planning process across the public sector.

Further, the recent Work Instruction N° 2/2017 requires the updating of information related to the observations and their status of regularisation. The information generated from this work is then included both in recurring audit reports (where prior audits are referred to in the background section) and year after year in the Internal Control System Evaluation Reports, which are carried out for each entity.

During mission interviews in October 2017, the OECD found that SIGEN had assisted agencies with setting up control committees in approximately 30 entities – with the goal to roll out the concept to the almost 200 unique entities in the public sector. Since Decree No. 72/2018 was issued in January 2018, all entities in the national public sector are required to establish a control committee. According to Article 1 of this decree, each committee is required to meet at least twice each year, with attendance to include the superior authority of the entity (or a nominated representative), the head of the internal audit unit, a representative from SIGEN, and those responsible for the operational areas of the entity.

These committees will be valuable for monitoring the implementation of audit recommendations. This concept is similar to the audit committee model in use in OECD countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. Argentina could consider following this ‘audit committee’ model more closely, where each entity has an audit committee that is independent from the day-to-day activities of management and regularly reviews the entity’s systems of audit, risk management and internal control as well as its financial and performance reporting. These committees are well positioned to assess and track the entity’s implementation of audit recommendations. The Australian example is provided at Box 5.4.

It is a requirement of Australia’s Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) that every Australian Government entity has an audit committee.

An independent audit committee is an important element of good governance as it provides independent advice and assurance to the head of an entity on the appropriateness of the entity’s accountability and control framework. It also independently verifies and safeguards the integrity of an entity’s financial and performance reporting.

In Australia, an audit committee must consist of at least three persons who have appropriate qualifications, knowledge, skills and experience to assist the committee to perform its functions. The majority of the members of the audit committee must be persons who are not officials of the entity.

The functions of the audit committee need to be outlined in a charter and must include that the committee will review the appropriateness of the entity’s:

-

financial reporting;

-

performance reporting;

-

systems of oversight (including internal and external audit);

-

systems of risk management; and

-

systems of internal control.

In relation to the audit function, audit committees may :

-

advise the head of the entity on the internal audit plans of the entity;

-

advise about the professional standards to be used by internal auditors in the course of carrying out audits in the entity;

-

review the adequacy of the entity’s response to reports of internal and, as far as practicable, external audits – including the entity’s response to audit recommendations; and

-

review the content of reports of internal and external audits to identify material that is relevant to the entity, and advise the accountable authority about good practices.

The distinguishing feature of an audit committee is its independence. The committee’s independence from the day-to-day activities of management helps to ensure that it acts in an objective, impartial manner, free from conflict of interest, inherent bias or undue external influence.

Source: (Department of Finance, 2015[17]; Department of Finance, 2015[18]).

5.6. Strengthening the supreme audit institution

The integrity of a government relies not only on an effective risk management, internal control and internal audit framework, but also on a strong external audit function – that, among other things, provides external oversight for the risk management and internal control framework. To this end, a country’s supreme audit institution should have a clear mandate and be independent, transparent and effective.

5.6.1. Argentina’s National Congress could strengthen the functional independence of the AGN by increasing the AGN’s power to select its own audit topics and by clearly outlining the AGN’s independence and mandate in a specific organic law

In Argentina, the external audit function is provided by the Auditoría General de la Nación (AGN). The AGN is a collegiate board model supreme audit institution with seven members –a President and six auditors general. The President of the AGN is appointed by the National Congress under the proposal of the opposition party for a renewable term of 8 years; if the opposition party changes, a new president is appointed. The remaining six members of the Board are elected for on 8-year renewable terms – with three selected by the Senate and three selected by the Chamber of Deputies, along political party lines.

The AGN received constitutional status as a legislative body in 1994. Article 85 of the National Constitution of Argentina states that “the Legislative Power is exclusively empowered to exercise the external control of the national civil service” with its opinions to be based on the reports of the AGN. Article 85 further states that the AGN is a technical advisory body of Congress with functional autonomy”. It is in charge of the control of the legal aspects, management and auditing of all the activities of the centralized and decentralized civil service (Argentina, 1994, p. 14[19]).

Article 85 also states that the AGN ‘shall be made up as established by the law regulating its creation and operation, which shall be approved by the absolute majority of the members of each House.’ Although the 1994 Constitution foreshadowed that an organic law specific to the AGN would be introduced, this law has been pending for 14 years.

The Auditor General’s functions are outlined in Article 118 of the Financial Administration Act (summary provided at Table 5.2).

OECD country SAIs are established under specific laws that outline, among other things, the powers, responsibilities and independence of the Auditor General. For example, the Australian SAI is established under the Auditor-General Act 1997 (Australia, 1997[20]) and the Canadian SAI is established under the Auditor General Act 1985 (Canada, 1985[21]). Within the Latin American and Caribbean context, the SAI of Argentina is the only one that does not have an organic law—with the following 17 countries introducing organic laws for their SAIs between 1953 and 2002: Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela (Santiso, 2009, pp. 52–55[13]).

In its 2013–17 Strategic Plan, the AGN outlined, as one of its strategic objectives, that it would “strengthen the identity of the AGN and its relationship with stakeholders” (AGN, 2013, p. 6[22]). A specific law regulating and outlining the creation, operation, powers, responsibilities, independence, and internal governance of the AGN would be beneficial for strengthening the independence, powers and identity of the AGN and for clarifying its mandate and relationship with stakeholders.

The AGN’s values are independence, objectivity, institutional commitment, probity, professionalism, and ethics. The Auditor General defines ethics as “observing the set of values and principles that guide our daily work”. The AGN is guided by the Government External Control Standards, which were based on INTOSAI’s International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI), as well as international best practices and professional standards in force in Argentina.

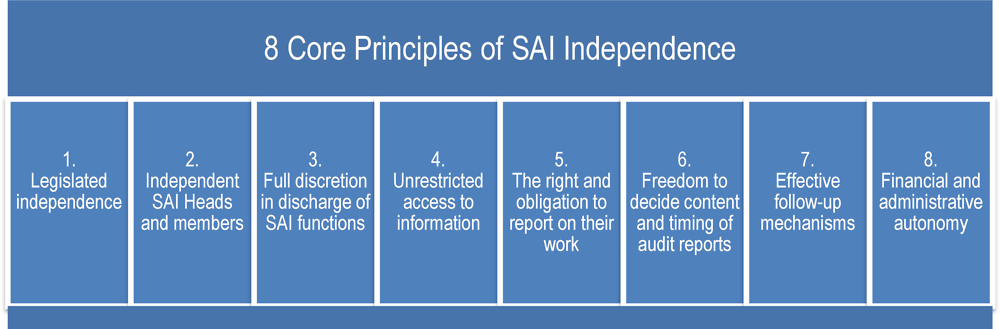

INTOSAI’s first cross-cutting priority for 2017–22 is the independence of SAIs. INTOSAI strongly advocates for and supports constitutional and legal frameworks that call for comprehensive audit mandates, unlimited access to needed information, and unrestricted publication of SAI reports. According to INTOSAI, “only fully independent, capable, credible, and professional SAIs can ensure accountability, transparency, good governance, and the sound use of public funds” (INTOSAI, 2017, p. 9[23]).

Argentina’s Government External Control Standards outline that all government external control work should contribute to the good governance by providing objective, independent, and reliable information (Auditor General of Argentina, p. 5[24]). The Standards further outline that the Auditor General must comply with basic ethical principles, such as: independence of judgement, objectivity and political neutrality (Auditor General of Argentina, pp. 10–12[24]).

Although the AGN’s values, standards and principles emphasise the importance of independence and political neutrality, the current structures and processes for the planning and approval of audits make it difficult for the AGN to undertake its functions in a completely independent and political neutral way.

The AGN’s main liaison point with the National Congress is through the Joint Parliamentary Committee of Audit, which has 12 members – 6 senators and 6 deputies. Each year, this committee elects a president, a vice-president and a secretary. The Joint Parliamentary Committee of Audit has a long history. It was first created in 1878 by Law No. 923. Its current powers arise from Law No. 24.156 – the Financial Administration Act (Senado Argentina, 2017[25]). According to Article 129 of the Financial Management Act, the committee must, among other things: approve the annual action programme on external control developed by the AGN; and instruct the AGN on studies and special investigations and set deadlines for their implementation, which does not align withinternational good practice.

INTOSAI has published a number of documents that cite the importance of independence for external auditors – which includes the need for independence in audit planning and the content and timing of audit reports. Further information is outlined in Box 5.5.

Ensuring audit institutions are free from undue influence is essential to ensure the objectiveness and effectiveness of their work, and principles of independence are therefore embodied in the most fundamental standards concerning public sector audit. The International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI), for example, has two fundamental declarations citing the importance of independence. Specifically, the “Lima Declaration of Guidelines on Auditing Precepts” (ISSAI 1) states that SAIs require organisational and functional independence to accomplish their tasks.

The “Mexico Declaration on SAI Independence” (ISSAI 10) and INTOSAI’s Strategic Plan 2017–2022 outline eight related principles of independence:

In relation to Principle 3 on functional independence, ISSAI 10 states that an SAI should have a sufficiently broad mandate and full discretion in the discharge of its functions, and SAIs should be empowered to audit the: use of public monies, resources, or assets; collection of revenues owed to the government or public entities; legality and regularity of government or public entities accounts; quality of financial management and reporting; and economy, efficiency, and effectiveness of government or public entities operations. Further information is provided in INTOSAI’s Guidelines and Good Practices Related to SAI Independence (INTOSAI, 2007[26]).

SAIs should be free from direction or interference from the Legislature or the Executive in the: selection of audit issues; planning, programming, conduct, reporting, and follow-up of their audits; organisation and management of their office; and enforcement of their decisions where the application of sanctions is part of their mandate.

Sources: (INTOSAI, 1977[27]; INTOSAI, 2007[28]; INTOSAI, 2017[23]).

Independence rarely happens to a supreme audit institution by accident. Independence needs to be planned for carefully and can take years of persistent work by many key partners – including the legislature, the Public Accounts Committee and the Ministry of Finance. Like any project, it is important that the SAI is clear about what it wants to achieve, has a full appreciation of the barriers and risks, makes a strong case to those who can help achieve the greater independence (such as the Public Accounts Committee), sets milestones and assigns responsibility for achieving those milestones. Wider support from stakeholders such as the media and civil society organisations can also help keep the campaign on track – if they are fully informed of the role of SAIs and the value of greater independence (National Audit Office, 2015, pp. 7–11[29]).

Once the legislature has agreed to consider developing new organic law, the AGN would need to work closely with the legislature and law commissions involved in drafting legislation so that they understand the areas of potential contention. The AGN would need to carefully review current legislation and compare this with the audit laws developed for other SAIs in similar circumstances – there would be no need to start from scratch (National Audit Office, 2015, p. 12[29]).

SAIs that are strong and functionally independent have greater credibility and are better able to effect change. There have been issues in recent years with the National Congress of Argentina ignoring audit reports submitted by the AGN – even those detailing serious cases of administrative irregularities and possible corruption (Manzetti, 2014, p. 192[30]).

The AGN could work with the National Congress to strengthen its functional independence, particularly by increasing the power of the AGN to select its own audit topics during the audit planning and audit approval processes and by clearly outlining the AGN’s independence and mandate in a specific organic law.

5.6.2. The AGN could strengthen its processes for the follow-up and monitoring of audit recommendations

As mentioned a core principle of SAI independence is effective mechanisms for the follow-up of audit recommendations (INTOSAI, 2007[26]). Audits help improve public administration and increase accountability and transparency when the audit findings are addressed and the audit recommendations are implemented. The SAIs for OECD member countries have a variety of methods for following-up recommendations. For example, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) conducts a selection of follow-up performance audits each year to assess entities’ implementation of performance audit recommendations from previous years. Australian government entities also have Audit Committees that meet regularly to, among other things, monitor the implementation of audit recommendations, and the ANAO can attend these meetings as an observer and/or request the meeting minutes. The Auditor-General has also written to entities to request an update on recommendations during the annual planning process for the audit work program.

In Canada, the office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, a sub-national audit office, has published follow-up reports based on self-assessments from audited entities and conducted follow-up audits on a selected number of them (see Box 5.6). The AGN could consider strengthening its processes to allow for the follow-up of recommendations, such as through a selection of follow-up audits or through organising annual self-assessments

The Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia (OAG) published a report entitled, Follow-Up Report: Updates on the Implementation Of Recommendations from Recent Reports, in June 2014. According to the then Auditor General of British Columbia, it was critical that the OAG follow up on the recommendations to ensure that citizens receive full value for money from the OAG’s work as the recommendations identify areas where government entities can become more effective and efficient.

The OAG did this by publishing a follow-up report that contained self-assessment forms completed by audited entities. These forms were published unedited and were not audited. The June 2014 report contained 18 self-assessments, two of which report that the entity had fully or substantially addressed all of the recommendations in their reports.

The OAG also followed up on their recommendations by auditing four self-assessments to verify their accuracy. The OAG found that in almost all cases, entities had accurately portrayed the progress that they had made to implement the recommendations. While the OAG sometimes found that recommendations were partially implemented rather than fully or substantially implemented as self-reported, the discrepancy usually resulted from a difference in understanding of what fully or substantially implemented meant. In those cases, the OAG worked with the ministries and agencies to clarify expectations and reach agreement on the status of the implementation.

Source: (Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia, 2014[31]).

5.6.3. The AGN could increase its influence by setting an example of transparency

In its 2013–17 Strategic Plan, the AGN outlined, as one of its strategic objectives, that it would “promote transparency and accountability in the national public sector” (AGN, 2013, p. 6[22]). Further, Section 6.ii of the Declaration of Asunción on Budget Security and Financial Stability of SAIs, which was signed by members of the Latin American and Caribbean Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (OLACEFS) on 4 October 2017, states:

As a guarantor of the proper use of public resources, we must subject ourselves to a process of oversight that gives transparency to the proper management of the funds that the entity receives and administers.

Supreme Audit Institutions, such as the AGN, should set an example for the public sector on transparency and on administering public funds with regard to efficiency, effectiveness and economy. Currently, the AGN provides little to no information on its website particularly regarding its discretionary expenditure. The AGN would increase its influence and credibility by providing the public with information on the AGN’s discretionary spending. This would serve as an example of transparency for the rest of the public sector. A good practice on SAI transparency from the Canadian Office of the Auditor General is presented in Box 5.7.

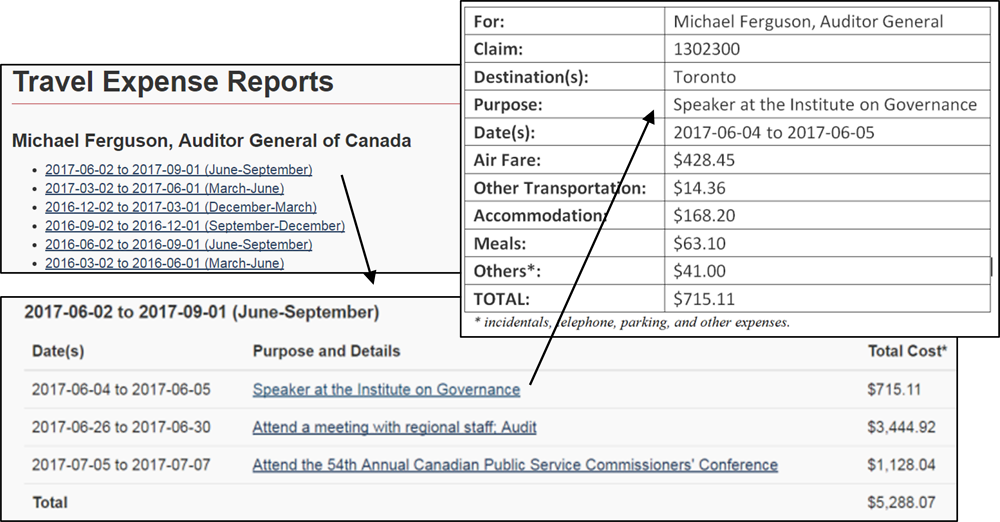

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) has a prominent section on its website entitled Transparency. This includes information on its audit practice accountability (such as detail on its external reviews and internal audits), office operations (such as travel, hospitality, contracts and client surveys) and access to information.

The OAG publishes annual travel reports on its website, as well as quarterly travel expense reports for the Auditor General and all of its executives. Reporting is timely. For example, the OECD accessed the reports for June to September 2017 (as well as all previous quarters going back to 2011) on 18 October 2017. With a few clicks, it was easy to see the details of expenditure for each trip.

Proposals for action

Argentina has established an internal control and risk management framework that aligns in many areas with international better practices, however, more could be done to strengthen the implementation of the framework and to build capacity in their internal control and risk management environment. Specific proposals for action that Argentina could consider are outlined below.

Establishing a control environment with clear objectives

SIGEN could ensure that clear objectives for the control environment are communicated to staff across the national public sector by:

-

including mandatory training on control objectives and requirements;

-

introducing awareness programs on the need for internal control and on the roles of each area and staff member; and

-

induction training for all staff, including senior management and managers on the internal control system

-

clearly outlining standards for specific roles; and

-

embedding controls into the daily operations of the public service

SIGEN could assist government entities to more consistently apply the principles of the three lines of defence model by:

-

giving greater responsibility for internal control and risk management to operational management;

-

assisting government entities with capacity building; and

-

building on already existing training and awareness activities for public servants, to help ensure they understand and consistently apply the internationally recognised three lines of defence model across the public sector.

Developing a strategic approach to risk management

SIGEN could improve its risk management approach to ensure it is consistent and clearly separated from the internal audit function by:

-

improving its risk management framework to be more strategic, consistent, and operational;

-

incorporating a risk management tool that is clearly separated from the audit function;

-

giving operational managers the ability to undertake risk assessments without the fear of reprisal;

-

maintaining a separate risk assessment process undertaken by auditors in their audit planning.

SIGEN could promote the incorporation of risk management into the culture of government entities by:

-

providing clear guidance for operational staff; and

-

including risk management requirements in mandatory training and induction sessions.

Argentinian government entities could operationalise the risk management framework by:

-

assigning clear responsibility for specific risks, including fraud and corruption risks needs, to the appropriate senior managers;

-

managers taking ownership of the risks that could affect their objectives;

-

managers using risk information to inform decision-making;

-

managers actively monitoring and managing their assigned risks; and

-

holding managers accountable to the executive through regular reporting on risk management.

Implementing coherent internal control mechanisms

SIGEN could assist government entities to strengthen its internal control mechanisms to ensure that they are implemented and effective and that reasonable assurance is provided by:

-

aiming control activities at reducing the risks that can affect the achievement of the objectives of the organisation;

-

ensuring that internal control activities are being implemented throughout each entity, at all levels and in all functions; and

-

ensuring that internal controls include a range of detective and preventive control activities.

Improving the internal audit function

SIGEN could ensure that its central coordination of internal audit leverages available resources to strengthen oversight and enable a cohesive response to integrity risks by:

-

building on the existing annual audit risk map and guidelines for internal audit planning by establishing dedicated strategic integrity objectives and by identifying trends and systemic issues; and

-

giving management the ability to respond to integrity risks, in a cohesive and holistic way—through reporting on the status of integrity risks, trends and issues that are systemic across the public service.

All Argentinian government entities could implement control committees to better monitor the implementation of audit recommendations by:

-

setting up committees that are independent from the day-to-day activities of management and that regularly review the entity’s systems of audit, risk management and internal control; and

-

giving these committees the ability to assess and track each entity’s implementation of audit recommendations.

Strengthening the supreme audit institution

Argentina’s National Congress could strengthen the functional independence of the AGN by:

-

increasing the AGN’s power to select its own audit topics; and

-

clearly outlining the AGN’s independence and mandate in a specific organic law.

The AGN and Argentina’s National Congress could strengthen the follow-up and monitoring of audit recommendations through:

-

adding a selection of follow-up audits to their annual audit work program; or

-

organising annual self-assessments of entities by writing to the management of entities to ask for their assessment of the status of audit recommendation implementation. The AGN could then select a sample for further follow, as has been done by the British Columbia audit office.

The AGN could increase its influence by setting an example of transparency, by:

-

providing the public with information on the AGN’s discretionary spending. This would serve as an example of transparency for the rest of the public sector. This could be done by providing access to information on the AGN’s website—similar to how information is provided by the Australian SAI.

References

[22] AGN (2013), “Strategic Plan 2013-17”, http://oecdshare.oecd.org/gov/sites/govshare/psi/integrity/Shared%20Documents/Integrity%20Review%20of%20Argentina/FFM%20Mission%20Oct%202017/Follow%20up%20material/AGN/AGN%20PEI%202013-2017.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2017).

[4] Argentina (2016), National Financial Administration and Public Sector Control Systems Act, http://www.sigen.gob.ar/pdfs/ley24156.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2017).

[19] Argentina (1994), “Constitution of the Argentine Nation”, http://www.biblioteca.jus.gov.ar/argentina-constitution.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2017).

[24] Auditor General of Argentina (n.d.), Government External Control Standards/NORMAS DE CONTROL EXTERNO GUBERNAMENTAL Auditoría General de la Nación, https://www.agn.gov.ar/files/files/5%20NORMAS%20CONTROL%20EXTERNO%20GUBERNAMENTAL.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2017).

[20] Australia (1997), Auditor-General Act 1997, https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2016C00685 (accessed on 10 November 2017).

[21] Canada (1985), Auditor General Act, http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/a-17/ (accessed on 10 November 2017).

[10] Department of Finance (2016), “Building risk management capability”, https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/comcover-information-sheet-building-risk-management-capability.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[18] Department of Finance (2015), Audit Committees, https://www.finance.gov.au/resource-management/accountability/audit-committees/ (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[17] Department of Finance (2015), “Resource Management Guide No. 202: Audit committees for Commonwealth entities and Commonwealth companies”, No. 202, https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/RMG-202-Audit-committees.pdf?v=1. (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[5] Institute of Internal Auditors (2013), IIA Position Paper: The Three Lines of Defense in Effective Risk Management and Control, https://na.theiia.org/standards-guidance/Public%20Documents/PP%20The%20Three%20Lines%20of%20Defense%20in%20Effective%20Risk%20Management%20and%20Control.pdf.

[23] INTOSAI (2017), “INTOSAI Strategic Plan 2017-2022”, http://www.intosai.org/fileadmin/downloads/downloads/1_about_us/strategic_plan/EN_INTOSAI_Strategic_Plan_2017_22.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2017).

[3] INTOSAI (2010), “Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector”, INTOSAI Guidance for Good Governance, No. GOV 9100, http://www.issai.org/en_us/site-issai/issai-framework/intosai-gov.htm (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[12] INTOSAI (2010), “Guidelines for Internal Control Standards for the Public Sector”, INTOSAI Guidance for Good Governance, No. GOV 9100, http://www.issai.org/en_us/site-issai/issai-framework/intosai-gov.htm (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[26] INTOSAI (2007), ISSAI 11 - INTOSAI Guidelines and Good Practices Related to SAI Independence, http://www.issai.org/en_us/site-issai/issai-framework/2-prerequisites-for-the-functioning-of-sais.htm (accessed on 6 July 2018).

[28] INTOSAI (2007), “Mexico Declaration on SAI Independence”, International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI), No. 10, INTOSAI Professional Standard Committee Secretariat, Copenhagen, http://www.issai.org.

[27] INTOSAI (1977), “Lima Declaration of Guidelines on Auditing Precepts”, International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI), No. 1, INTOSAI Professional Standard Committee Secretariat, Copenhagen, http://www.issai.org.

[9] ISO (2009), ISO 31000-2009 Risk Management, https://www.iso.org/iso-31000-risk-management.html.

[30] Manzetti, L. (2014), “Accountability and Corruption in Argentina during the Kirchners’ Era”, Latin American Research Review, Vol. 49/2, https://lasa.international.pitt.edu/LARR/prot/fulltext/vol49no2/49-2_173-196_manzetti.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2017).

[29] National Audit Office (2015), Making SAI independence a reality: Some lessons from across the Commonwealth, http://www.intosai.org/fileadmin/downloads/downloads/4_documents/Commonwealth_Making_SAI_independence_a_reality.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2017).

[11] OECD (2017), Government at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/gov_glance-2017-en.

[1] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, http://www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/Recommendation-Public-Integrity.pdf.

[31] Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia (2014), Follow-Up Report: Updates on the Implementation Of Recommendations from Recent Reports, http://www.bcauditor.com/sites/default/files/publications/2014/report_19/report/OAGBC%20Follow-up%20Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[13] Santiso, C. (2009), The Political Economy of Government Auditing: Financial Governance and the Rule of Law in Latin America and Beyond, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, http://www.u4.no/recommended-reading/the-political-economy-of-government-auditing-financial-governance-and-the-rule-of-law-in-latin-america-and-beyond/ (accessed on 23 October 2017).

[25] Senado Argentina (2017), Joint Parliamentary Committee of Audit webpage, http://www.senado.gov.ar/parlamentario/comisiones/info/100 (accessed on 4 September 2017).

[16] SIGEN (2017), 2017 Annual Plan, http://www.sigen.gob.ar/plan-anual.asp (accessed on 7 September 2017).

[2] SIGEN (2014), General Internal Control Standards for the National Public Sector/Normas Generales de Control Interno Para el Sector Publico Nacional, SIGEN, http://www.sigen.gob.ar/pdfs/normativa/ngci.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2017).

[15] SIGEN (2002), Internal Audit Standards, http://www.sigen.gob.ar/normas-06.asp (accessed on 7 September 2017).

[8] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2018), Organizational Structure, https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/corporate/organization.html (accessed on 18 January 2018).

[7] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2017), Framework for the Management of Risk, http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=19422 (accessed on 17 January 2018).

[6] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2017), Policy on Internal Audit, http://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=16484 (accessed on 17 January 2018).

[14] United Kingdom Government Internal Audit Agency (2018), About us, https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/government-internal-audit-agency/about (accessed on 18 January 2018).