Executive summary

The euro area response to the crisis was strong and followed by a swift recovery, but risks remain.

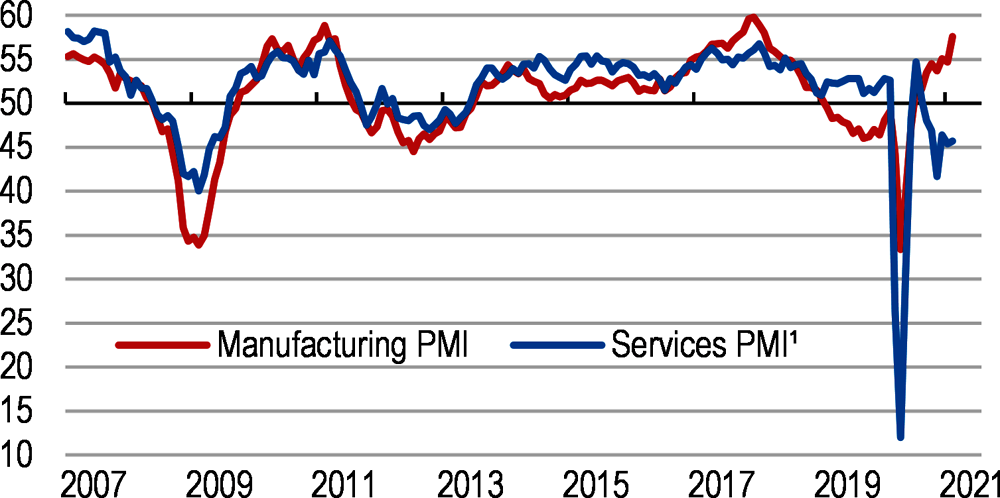

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic led the euro area into its worst recession. Several waves of infections forced most euro area economies into repeated lockdowns, curbing economic activity, especially in the service sector (Figure 1). The policy reaction to the crisis was rapid and effective. On the monetary policy side, immediate ECB action helped to shore up bank lending and liquidity. On the fiscal policy side, the EU activated the general escape clause of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) – which allows temporary deviations from SGP budgetary targets – and, among other measures, it agreed on common tools to support national short-time work schemes, and set up an ambitious plan to promote economic recovery and accelerate the green and digital transitions (Next Generation EU).

The recovery is firming up, however, the pandemic could have persistent economic consequences and fiscal support should not be withdrawn prematurely (Table 1). In some sectors the pandemic may weaken demand durably and unemployment could remain high for longer. Moreover, disruptions to the education system may affect the human capital of future generations, negatively affecting future growth. Given these challenges, European policymaking should not be complacent when the health crisis will be over. Fiscal policy should keep supporting affected sectors until the recovery is firmly established, avoiding premature consolidations. Moreover, a durable recovery will require the completion of an ambitious reform agenda, and would be supported by reforms to the economic architecture of the currency union.

Monetary policy accommodation should continue until inflation robustly converges to the ECB target. The new framework will help the conduct of monetary policy.

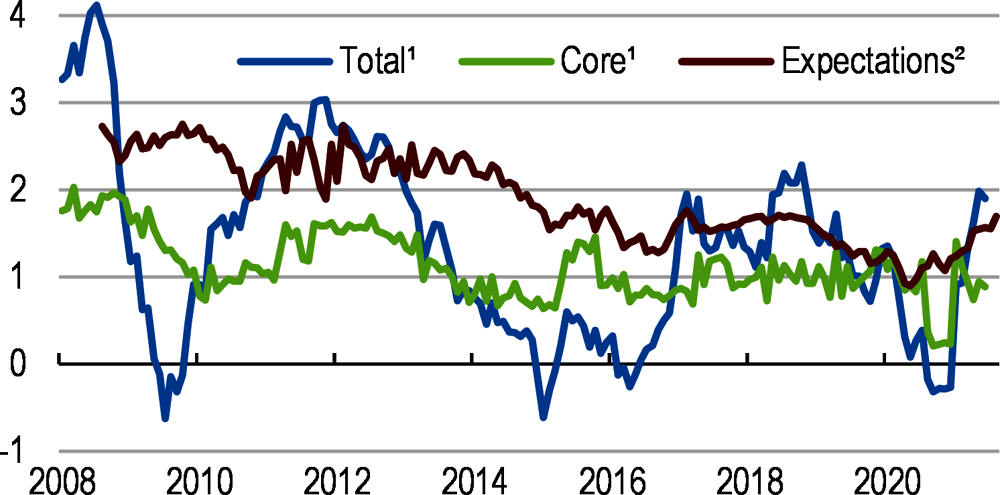

The ECB policy support in the wake of the crisis has been prompt and forceful. Newly introduced monetary policy measures included a set of longer-term refinancing operations at very favourable conditions, easing conditions on the existing and new targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), collateral easing measures and a large expansion of the central bank’ asset purchases. Such measures succeeded in calming financial markets. However, even if picking up in 2021 (Figure 2), inflation over the medium-term is still off from the ECB objective. Against this background, monetary support is still required.

The ECB has completed a review of its monetary policy strategy. The review brought welcome changes, such as emphasised symmetry in the monetary policy objective, guidelines for improved ECB communication and an action plan for the incorporation of climate change considerations into the monetary policy framework. In the current context, vigilance should remain high against possible negative side effects of protracted easing measures, such as unsustainable asset price dynamics in financial and real estate markets.

The evaluation of EU fiscal rules should aim at improving the fiscal framework. New crisis-related fiscal tools should be deployed quickly and their assessment should feed the debate on the completion of the monetary union.

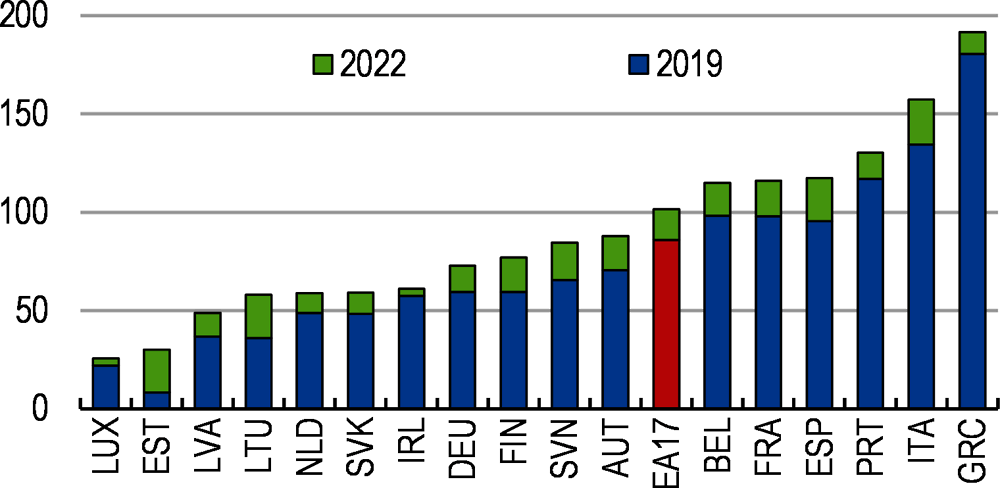

The COVID-19 crisis poses new challenges to the current fiscal framework. At times, European fiscal rules did not prevent pro-cyclical fiscal policy, and the framework has become too complex. The COVID-19 crisis significantly worsened fiscal balances causing public debt to rise to new highs (Figure 3). While the existing framework has flexibility margins, strict compliance with it would require large consolidations efforts over the coming years, risking to derail the recovery. Against this background, the current set of fiscal rules should be evaluated with the aim to better ensure sustainable government finances, sufficient counter-cyclicality and greater ownership. Fiscal prudence could be encouraged through strengthening the involvement of independent fiscal institutions, by enhancing medium term budgetary frameworks, and by considering positive incentives.

Common European, crisis-related fiscal instruments should be deployed fast. SURE and Next Generation EU represent a remarkable achievement. EU countries should focus on a prompt implementation of the recovery and resilience plans to deliver structural reforms and investment based on sound cost-benefit analysis. At a later stage, the economic impact of SURE and Next Generation EU should be rigorously assessed as they could provide valuable inputs to the debate on the completion of the EMU architecture.

Resilient labour markets will help the economic rebound. Strengthening the single market for capital will reduce the risk of financial fragmentation.

After the global financial crisis, large differences in business cycles across euro area countries emerged. These differences developed into diverging economic paths for hardest hit economies, threatening economic convergence and European cohesion. The COVID-19 pandemic again has affected euro area economies differently, raising the risk of economic divergence inside the currency union. This calls for policies to foster cyclical convergence, to ensure that no country will be left behind during the recovery.

More resilient labour markets increase the capacity of the economy to absorb shocks and accelerate the recovery. Job retention schemes (JRSs) have proven effective in preserving employment in the face of large economic shocks. To ensure a prompt recovery of labour markets, the phase out of JRSs should be paired with augmented job mobility policies. In this regard, active labour market policies and training programmes should be extended to workers under JRSs.

Cross-border labour mobility can be effective in abating differences in domestic labour markets. However, despite having increased over the last decade, labour mobility across euro area countries was still limited before the pandemic. An extension of automatic recognition of professional qualifications, and the complete implementation of the Electronic Exchange of Social Security Information could effectively support cross-border labour mobility.

The European banking system is not yet fully integrated, contributing to financial fragmentation and economic divergence after the financial crisis. Deposits in euro area banks are vulnerable to shocks in individual countries, and discussions are ongoing in the High Level Working Group on a European Deposit Insurance Scheme (HLWG on EDIS). Completing the banking union would require to address all outstanding issues in a holistic manner and with the same level of ambition.

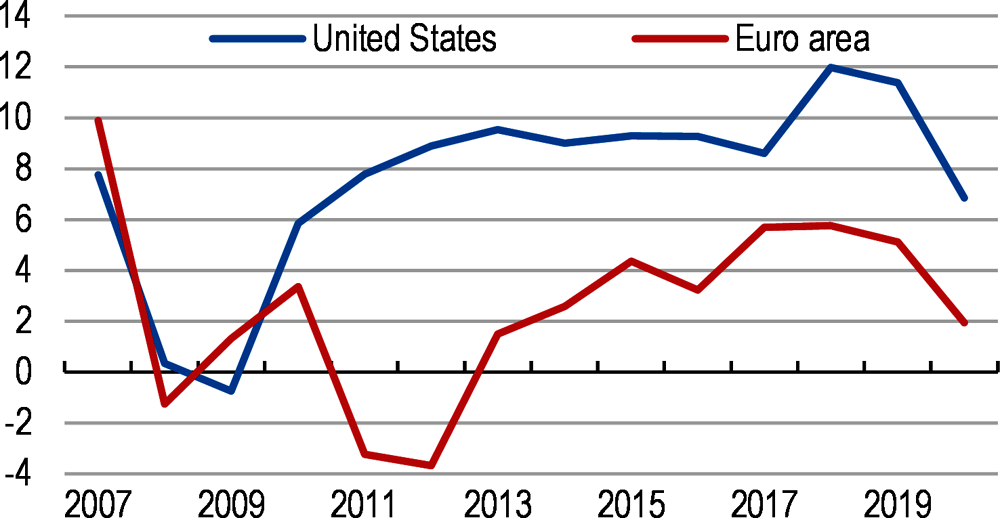

Financial authorities should strengthen the European framework to deal with NPLs. Bank profitability could be further weakened by a possible new wave of non-performing loans (Figure 4). Supporting banks dealing with NPLs will require approving ongoing reforms on foreclosing procedures and supporting the development of secondary markets. The establishment of a network of Asset Management Companies (AMCs) should also be considered.

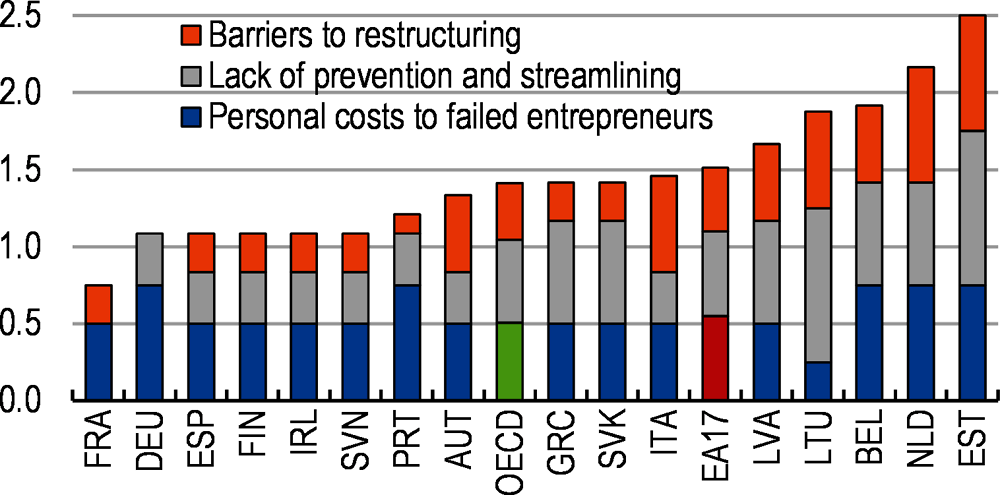

Reducing the reliance of European financial markets on banks is a priority. Higher diversification in sources of funding for corporates would allow to increase the resilience of credit to firms during downturns, avoiding that possible bank distress could lead to financial fragmentation. Several aspects of the Capital Markets Union remain incomplete, most notably the development of securitisation and equity markets together with the convergence of national frameworks regarding financial market regulation, supervision, and insolvency proceedings (Figure 5).

Increasing fiscal integration is key to reduce divergence in business cycles and strengthen the stability of the euro area in case of shocks. A common fiscal capacity is one of the main tools for business cycle stabilisation and cyclical convergence in a currency union, and it remains a missing feature of the euro area. The establishment of a common fiscal capacity should be considered to complement the capacity of euro area member states to conduct counter-cyclical fiscal policy.