1. Earnings-related public pensions

This chapter analyses public earnings-related pensions in Slovenia compared with other OECD countries. It first provides contextual information related to demographic developments and labour market performance. The chapter then discusses pension eligibility conditions and benefit calculation rules, as well as their implications for future replacement rates for employees, civil servants and the self-employed. It shows the implications of career interruptions due to childcare or unemployment on future pensions.

This chapter reviews the parameters of the public earnings-related pension scheme and identifies the main weaknesses. However, it does not discuss issues directly related to financial sustainability, which is the focus of Chapter 2. This chapter starts by describing the demographic and labour market context in Section 1.2. Section 1.3 provides an overview of the pension system today and reform trends since its introduction in 1992. Pension eligibility conditions are then discussed in Section 1.4. The calculation of pensions is analysed in the next section (Section 1.5). Based on these, pension replacement rates are analysed, including full-career cases, the impact of incomplete careers due to unemployment and childcare on pensions (Section 1.6). An analysis of pension rules for the self-employed follows (Section 1.7).

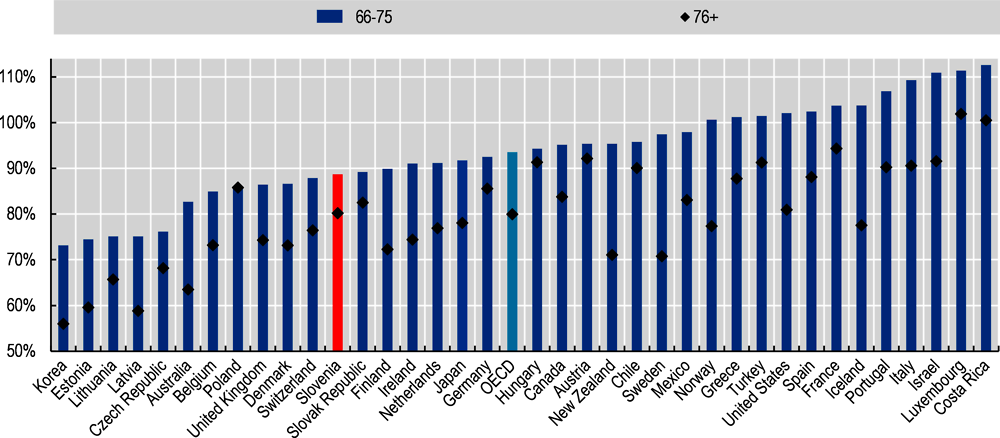

1.2.1. Relative income of older people close to OECD average

As in many OECD countries, older people in Slovenia have on average a lower disposable income than the entire population (Figure 1.1). The average disposable income of the 66-75 age group is equal to 89% of that of the full population, below the OECD average of 94%. This relative income ratio is below 80% in the Baltic states, the Czech Republic and Korea while it exceeds 100% in 12 OECD countries including Greece and Italy.

People aged 76+ have a lower average income than the 66-75 in Slovenia as in all OECD countries except Poland. The mean disposable income of this age group equals 80% of that of the entire population in both Slovenia and the OECD on average. Across the OECD, this ratio varies from less than 60% in Estonia, Korea and Latvia to more than 90% in Austria, Chile, Costa Rica, France, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Turkey.

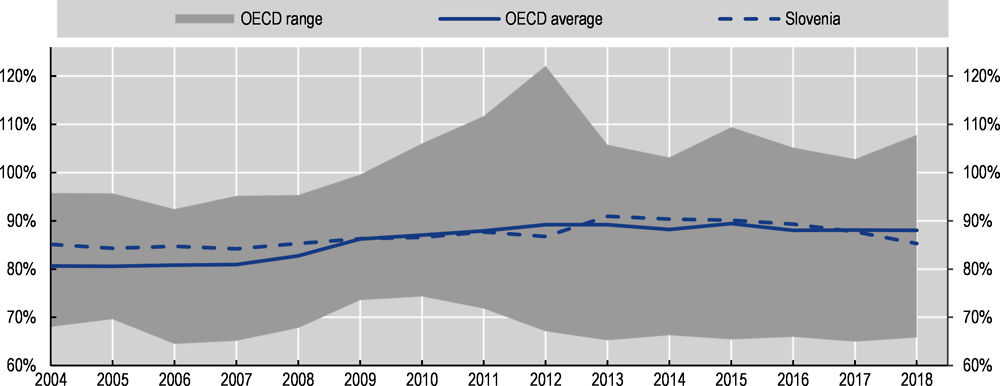

The relative income of people older than 65 improved in Slovenia between 2004 and 2015 from 85% to 90%, but it declined slightly thereafter. The average income of older people increased faster in the OECD on average from 80% of that of the entire population in 2004 to 88% in 2018 (Figure 1.2).

With a Gini coefficient – a measure of inequality that equals 0 if every person receives the same income and 1 if one person receives all income – of 0.256 among the population aged 66 and over, old-age income inequality in Slovenia is substantially below the OECD average of 0.304. The Slovenian level is comparable to that of Germany, Hungary and Poland. Relative poverty among older people is just below the OECD average (Chapter 3).

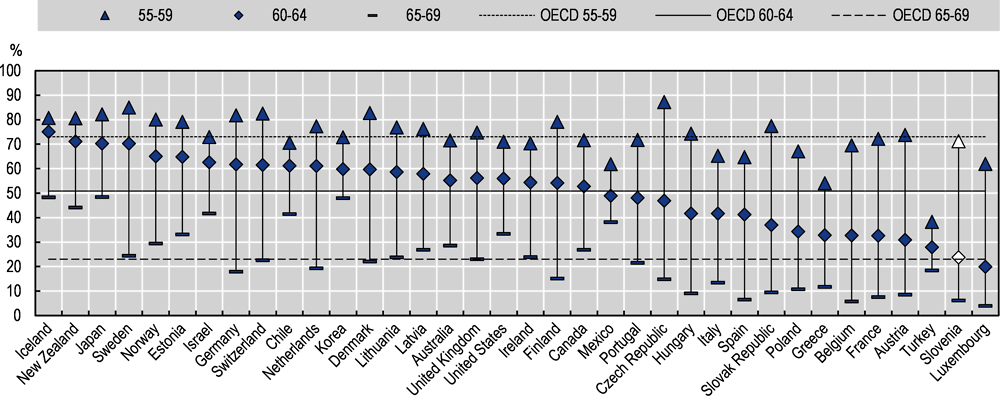

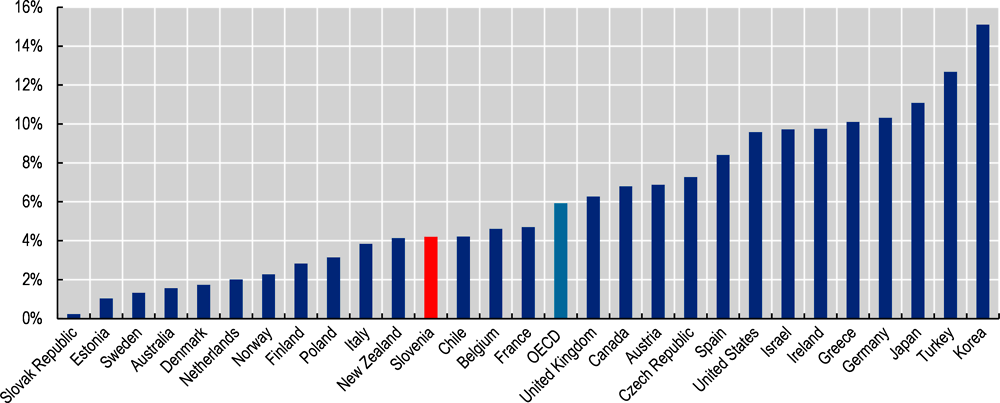

1.2.2. Employment after age 50 has been increasing but still plummets around age 60

Employment after age 60 is very low in Slovenia. In 2019, 68.6% of people aged 55-59 were employed in Slovenia, only slightly below the OECD average (Figure 1.3). The drop of employment at older ages is much sharper in Slovenia than in most OECD countries. In the 60-64 age group, one-quarter of Slovenians were in employment, half of the OECD average. The employment rate for this age group is lower only in Luxembourg. Similarly, among the 65-69, the employment rate in Slovenia at 6.2% remains well below the OECD average of 23.0%, with several Central and Eastern European countries having a similar rate, including Hungary at 9.1%, Poland at 10.8% and the Slovak Republic at 9.5%, as well as Austria at 8.6%.

However, employment of people in their fifties has significantly improved over the last two decades (Figure 1.4). Between 2000 and 2019, male employment increased by 9 percentage points to 87% in the age group 50-54, just above the OECD average level. Over the same period and for the same age group, the female employment rate increased even stronger by 35 percentage points, to 86%, compared to the OECD average of 75%. In 2019, only the Czech Republic and Sweden had higher employment rates among women aged 50-54.

While the Slovenian employment rates in the age group 55-59 were among the lowest in the OECD in 2000, employment increased among both men and women over the last two decades. Much less than half of men (44%) in this age group were in employment in 2000, increasing to three-quarters (75%) by 2019, reducing the substantial gap with the OECD average to less than 5 percentage points. The employment rate among women in this age group took off over this period, from 17% to 68% between 2000 and in 2019, surpassing the OECD average in 2018.

Employment rates in the age group 60-64 have increased less strongly since 2000. Male employment in this age group increased by around 10 percentage points to 29% in 2019, and from 10% to 19% among women. Throughout this period, Slovenia consistently was among the countries with the lowest employment rates for both men and women in this age group.

Finally, in the age group 65-69, employment fell over this period. In 2000, 16% of men and 10% of women in this age group were in employment, compared to 8% and 4%, respectively, two decades later. Over the same period, the average employment rate among people aged 65-69 in the OECD increased. As a result, the difference between the employment rate in Slovenia and the OECD average increased from 6 percentage points in 2000 to 26 percentage points in 2019 for men, and from 1 to 18 percentage points for women over the same period.

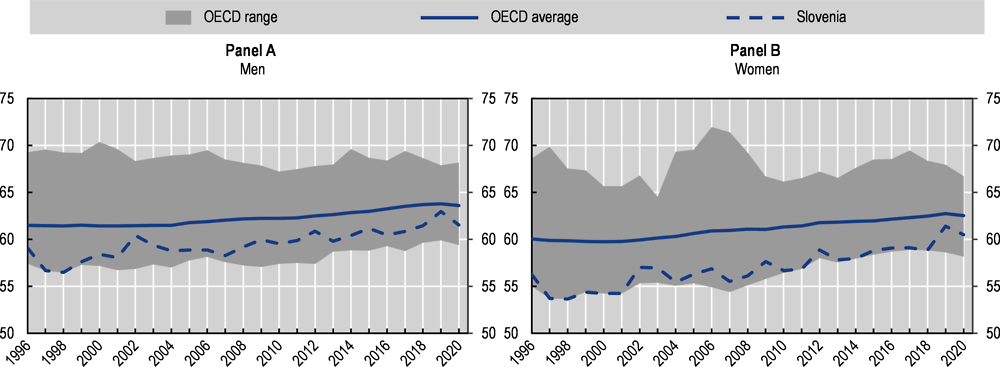

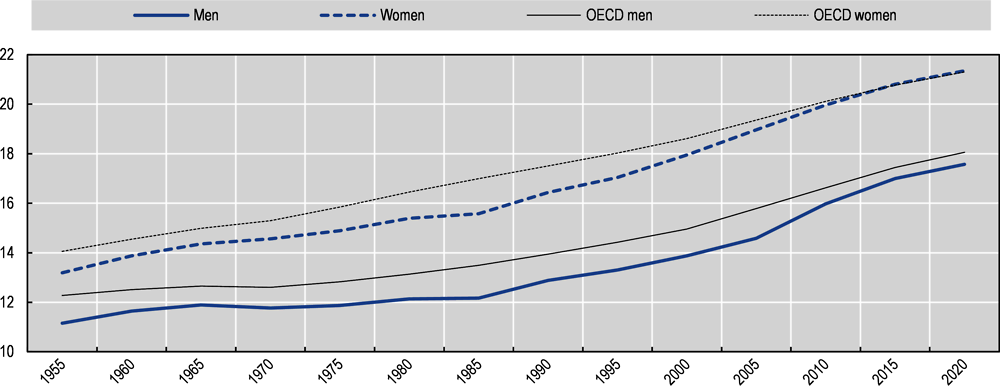

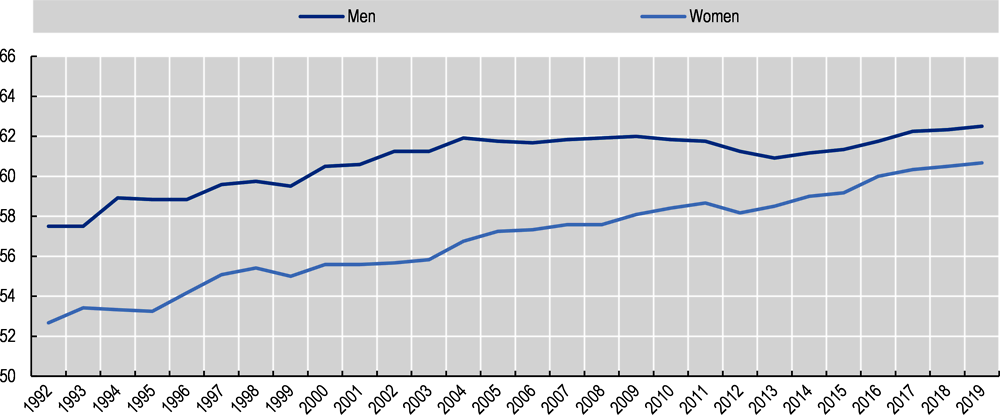

Correspondingly, Slovenia has systematically been among the OECD countries with the lowest average labour market exit age, especially for women (Figure 1.5). Steadily increasing from around 57 years in the late 1990s, the male average labour market exit age reached 61.5 years in 2020. Over the same period, it increased from around 54 to 60.5 years among women. Across OECD countries, men and women on average left the labour market at substantially older ages in 2020, 63.8 and 62.4 years, respectively. On top of Slovenia, eight other OECD countries have an average labour market exit age of 61.0 years or below, when averaging men and women.

1.2.3. Population ageing will be accelerating at a fast pace

Life expectancy in Slovenia is now close to the OECD average

Life expectancy at age 65 increased faster in Slovenia than in the OECD on average over the last decades (Figure 1.6). Women’s life expectancy at 65 caught up with the OECD average around 2010, reaching 21.4 years in 2020. Male life expectancy at age 65 has also increased faster in Slovenia since 2000, but remained half a year below the OECD average at 17.6 years in 2020. Based on UN projections, remaining life expectancy would grow in the future by about 0.9 years per decade for women, while it would grow faster for men by 2040 (1.3 years) before slowing to 1.0 year per decade.

Working-age population will shrink in Slovenia

The working-age population (20-64) is projected to decrease by 10% in the OECD on average between 2020 and 2060, i.e. by 0.26% per year. The projected fall in Slovenia will be much larger, by 27%, but substantially less than by around 40% in Latvia, Lithuania and Poland (Figure 1.7). This will lower future contribution revenues posing challenges to the financial sustainability of pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) pensions. By contrast, in Australia, Israel and Mexico, the working-age population is projected to grow by more than 20% by 2060.

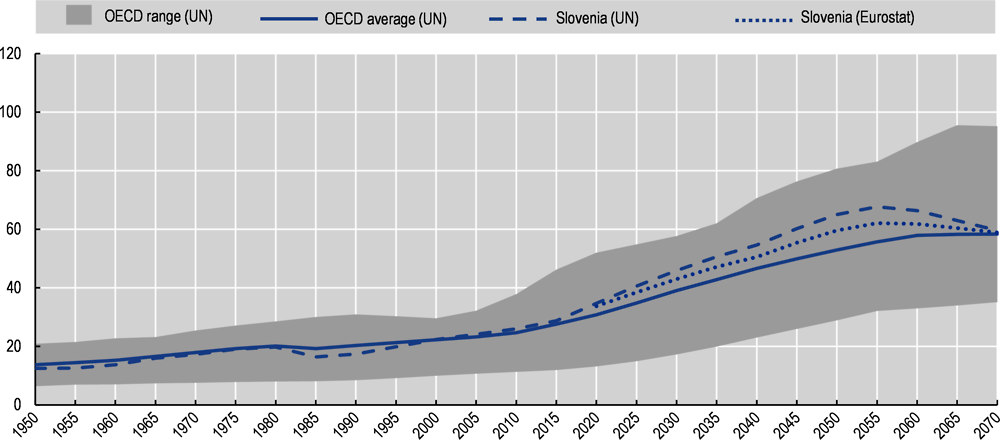

Demographic old-age to working-age ratio has accelerated

By 2050, Slovenia is projected to have 65 people aged 65+ per 100 people aged 20-64 against an OECD average of 53 (Figure 1.8). Slovenia’s demographic old-age to working-age ratio would be the seventh highest in the OECD, after Japan and Korea, and Southern European countries with a ratio of 71 for example in Portugal and 78 in Spain. Among other Central and Eastern European countries, it would range from 53 in Hungary to 60 in Poland.

These 2050 old-age to working-age ratios are much higher than current levels of 35 for Slovenia and 31 for the OECD on average, which are themselves up from 17 and 20, respectively, in 1990. Figure 1.9 shows that this ratio is projected to peak at 68 around 2055 in Slovenia and highlights that the pace of ageing (as measured by the increase in this indicator) is expected to be significantly faster than in the OECD on average in the next three decades. By comparison, Eurostat projects a somewhat slower shift in the demographic structure than based on UN data, with the old-age to working-age ratio reaching 62 in 2055 in Slovenia. Different migration assumptions partially explain the differences between Eurostat’s and UN’s projections.1

This section presents pension rules in Slovenia as of 2020 and the evolution of these rules since the introduction of the current pension system in 1992. An in-debt analysis of these rules in international perspective follows in the next sections.

1.3.1. Public pension system today

The pension system in Slovenia consists of the public pension scheme, occupational pensions and voluntary individual schemes. Occupational schemes are funded, defined contribution and voluntary except for civil servants and persons employed in hazardous and arduous occupations, for whom mandatory occupational pensions top up the universal scheme. Chapters 5 and 6 cover individual and occupational private pension arrangements.

Eligibility conditions to public pension

Eligibility to an old-age pension requires being 60 or older and having worked, and contributed, for at least 40 years. This period of paying contributions whilst working is called the “pensionable service without purchase” in the Slovenian pension law and it includes all work-related periods for which contributions have been paid, e.g. dependent employment, self-employment, agricultural activity, unemployment spells or parental leave, but it does not include the insurance periods based on either purchased periods or voluntary contributions. Alternatively, one can claim an old-age pension at age 65 with at least 15 years of insurance period. “Insurance period” is a broader term and it includes all periods for which contributions have been paid. Based on having children, military service or having started the career before the age of 18, the age condition can be lowered to 56 and 58 for women and men with 40 years of pensionable service without purchase, respectively, while 38 years of pensionable service without purchase grant eligibility in those cases from age 61. It is also possible to purchase up to 5 years of insurance, but the purchased contributions are not used to relax age requirements. If the eligibility conditions are met thanks to purchased periods, retiring before age 65 is subject to a permanent reduction of 3.6% for each year before age 65, capped at 18% in total. Very few people use this option.2

Public pension entitlements

The Slovenian public pension scheme covers all workers and is mandatory, defined benefit and pay-as-you-go. Public pensions are administered by a governmental agency named Pension and Disability Insurance Institute (ZPIZ). The benefits are earnings-related and calculated by multiplying total accruals by the reference wage. In turn, the reference wage is the average of the best consecutive 24 years of “adjusted” earnings, with past earnings valorised by the average-wage growth. Earnings are adjusted every year by multiplying gross earnings by the ratio of net average wages divided by gross average wages; this ratio was equal to 64.63% in 2019.3 Hence, “adjusted” earnings are conceptually close to net earnings; they are exactly equal to net earnings at the average wage.

Pension entitlements require at least 15 years of contributions. They will be equal to 29.5% of the reference wage plus 1.36% of the reference wage for any additional year beyond the first 15 years for both men and women from 2025 onwards, when accrual rates of men have converged to those of women. As a result, from 2025 onwards, after 40 years of contributions a person can expect gross pension to replace 63.5% (= total accruals) of the reference wage (63.5% = 29.5% + 1.36%*25). As of 2019, men accrue 27% of the reference wage for the first 15 years and 1.26% of the reference wage for each additional year of contributions. Once eligibility conditions to pensions of age 60 with 40 years of pensionable service without purchase are met, continuing to work generates an annual accrual rate of 3% for the first three years instead of the standard 1.36%. The benefits during retirement are indexed to 40% of price inflation and 60% of average-wage growth.

On top, all pensioners receive an additional payment once a year, called the annual allowance. The benefit level is set discretionarily and has been higher for low pensions since 2013, ranging from EUR 437 in 2019 for monthly pensions lower than EUR 470 (hence boosting low pensions by at least 7.7%) to EUR 127 for pensions higher than EUR 810 (hence increasing high pensions by at most 1.3%). This compares with the average annual pension of EUR 8 052 in 2019 (or 671 per month).

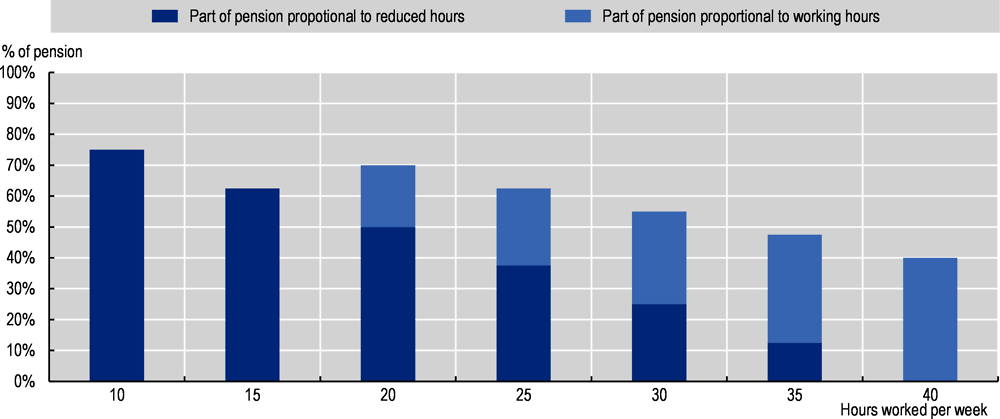

Part-time workers acquire pension rights proportionally to their working hours (relative to full-time working hours of 40 hours per week). Working part time affects pension entitlement through lower accruals, but not through the reference wage. More precisely, total accruals take into account the working time while for reference wage calculation, the wage of a part-time worker is converted into a full-time equivalent. For example, if a person works 20 hours a week for a year, only half a year is taken into account for total accruals. This also means that for eligibility conditions the insurance period for part-time work is also prorated. Someone who worked half-time during 28 years validates 14 years of contributions and is therefore not eligible to pensions. Consequently, part-timers need to work for longer periods to meet eligibility conditions.

Minimum pension

In the case of low earnings during the whole career, the reference wage is set at a minimum of 76.5% of the net average wage, thereby effectively providing a floor to the earnings-related pension, i.e. minimum pension. This minimum pension is by definition unrelated to past earnings and increases with the pensionable service from 22.6% of net average wage after a full-time career of 15 years to 48.6% after 40 years. On top of this floor, the reference wage is also subject to a ceiling, set at four times the minimum reference wage, which then imposes a ceiling to pension levels. Hence, earnings higher than about three times (~ 4 * 76.5%) the average wage do not generate any pension entitlements while there is no ceiling to contributions. Additionally, a guaranteed pension was introduced in 2017 at EUR 500 (EUR 620 in 2021) for those who have met full conditions regarding pensionable service (Chapter 3).

Survivor pensions

Survivor pensions are paid to widows and widowers and to other dependent family members, including children and parents. From 2022, claiming pensions after the death of a spouse will be possible from the age of 58 and being at least 53 when the death occurred. The right to a survivor pension applies also after a divorce if the deceased person paid alimony. Survivor pensions equal to 70% of the deceased’s pension but it is eligible only if the survivor does not work and does not receive an own pension. The survivor having an own pension can choose to combine it with the survivor pension, which in that case is reduced to 15% of the deceased’s pension subject to a ceiling of 11.7% of the minimum reference base, or to forego the own pension and receive the full survivor pension of 70%.4

Public pension finances

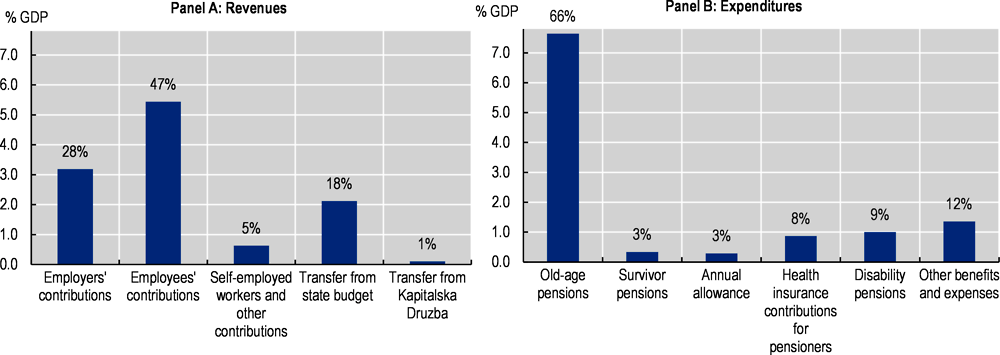

Old-age and survivor pensions are financed along with disability pensions from contributions equal to 24.35% of gross wages for employees5 – 15.50% paid by employees and 8.85% by employers – or of earnings for the self-employed, direct transfers from the state budget and a small transfer from publicly owned assets, managed by a state-owned enterprise, Kapitalska Druzba. In 2019, contributions covered 81% of all revenues while transfers from the state budget accounted for 18%, and transfers from Kapitalska Druzba covered the remaining 1% (Figure 1.10, Panel A). Any pension deficit is always financed by the state budget, in particular as there is no buffer fund.

ZPIZ expenditures equal 11.5% of GDP (2019 data), with old-age pensions, survivor pensions and the annual allowance representing 66%, 3% and 3% of total spending, respectively (Figure 1.10, Panel B). In addition, 8% of the social security budget finances health insurance of all pensioners. Indeed, while workers pay separate contributions to the National Health Insurance Institute at the rate of 12.92% (6.56% paid by employers and 6.36% by employees), pensioners do not pay any health contributions and the ZPIZ contributes for them at the low rate of 5.96%. Finally, 9% of ZPIZ expenditures relate to disability pensions, with about four-fifths of recipients of disability pensions being 60 or older. Other benefits account for 12% of spending and include mainly long-term care benefits. The financing of non-contributory benefits, which top up low pensions or are granted to those with less than 15 years of contributions, was shifted from the ZPIZ to the state budget in 2012 (Chapter 3).

1.3.2. Evolution of the Slovenian public pension system

The social security system in Slovenia originates in the 19th-century Austro-Hungarian Empire. A Bismarck-type social insurance system covered risks related to health, work accidents and old age, first for miners and then expanded to civil servants at the beginning of the 20th century. A population-wide old-age insurance was introduced after World War I in Yugoslavia, replaced by a new one in 1948 when all accumulated assets were nationalised and the system became fully pay-as-you-go (Kresal, 2013[3]; Stanovnik, 2002[4]). After Slovenia gained independence in 1991, the first national pension system was introduced in 1992. It inherited many elements of the Yugoslavian system along with the employment and earnings records dating back to the 1960s. Parametric reforms took place since 1992 within the PAYGO defined benefit framework. However, in contrast to many Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs), Slovenia did not go through a systemic reform.6 Table 1.1 summarises the main measures, which were taken as part of the 1999, 2012 and 2019 reforms.

Tighter eligibility conditions combined with lower retirement ages for having children

Since 1992, pension eligibility conditions have depended on both age and the length of insurance record. People were initially allowed to retire at 65 for men and 60 for women based on 15 years of insurance; for women, this age condition increased gradually to 65 between 2000 and 2016. Moreover, having 20 years of insurance used to provide access to pensions at younger ages.7 The 2012 law gradually eliminated this possibility, which was closed in 2020.

However, in the old system, the most frequent retirement option required 35 and 40 years of insurance period at age 50 and 55 for women and men, respectively. The 1992 law gradually increased the age conditions to 53 and 58 years, respectively, by 1998. The 1999 law gradually raised the insurance period condition to 38 years for women. Finally, the 2012 law gradually increased these eligibility conditions to 40 years of pensionable service without purchase at age 60 for all by 2019.8 The option to purchase up to 5 years of insurance period was maintained but retiring thanks to the purchased period has become subject to benefit reduction. Additionally, the age requirement to survivor pensions was increased from 53 to 58 years by 2022.

People who reached eligibility conditions before 2012 have retired following the previous rules. Figure 1.11 shows that until 2014, the majority of new pensions were granted following the previous law and that the transition was almost over by 2018 when 96% of new pensions followed the 2012 law.

The tightening of the eligibility conditions since 1999 was partially offset by providing exemptions for having children, to one of the parents. Which parent should benefit from the exemption was to be agreed between them. In 2000, the retirement age was lowered depending on the number of children. For each child, the reduction was initially of 0.50, 0.75, 1.00 and 1.25 months for the first, second, third and each subsequent child, respectively, and set to increase gradually to 8, 12, 16 and 20 months by 2015. However, the 2012 law limited these reductions to 6, 10, 10 and 10 months, respectively, and 12 months for the fifth child and 0 for any subsequent ones. In addition, a floor was introduced for the retirement age, at 56 and 58 years for women and men, respectively, while, upon meeting other eligibility conditions, the mother has become the default parent unless the father has received parental benefits.

Changes in pension calculation over the last two decades

Under the 1992 law, the reference wage was calculated based on wages from the 10 best consecutive years. This period was gradually extended to 18 years by the 1999 reform and to 24 years by the 2012 reform, to be fully effective by 2017. The impact of a longer reference period on pension levels and pension distribution is discussed in a subsequent section.

The 1992 law granted total accruals of 85% of the reference wage after 35 years of insurance for women and 40 years for men, i.e. 2.4% and 2.1% annual accrual rates, respectively. The total accrual could not exceed 85%, no matter how long the insurance period was. The uprating of past wages with average-wage growth was further adjusted by some complicated formula (Guardiancich, 2012[5]), resulting in the reduction of the reference wage by 16% in 2000 and 27% in 2012, compared to its value without this further adjustment (Majcen and Verbic, 2009[6]; Čok, Sambt and Majcen, 2010[7]), affecting all reference wages similarly, irrespective of the exact earnings trajectory.

The 1999 reform lowered total accruals to 72.5% after 38 and 40 years of insurance for women and men, respectively, i.e. to 1.9% and 1.8% annually, while eliminating the ceiling of 85%. There was a gradual phase-in for new pensions as the changes only affected entitlements accruing after 1999. The full effect would have thus been fully visible after 2020 when new pensioners would have worked most of their career under the 1999 law.

The 2012 reform lowered total accruals further to 64.25% and 57.25% after 40 years of contributions for women and men, respectively, i.e. to 1.6% and 1.4% annually. In addition, total accruals would gradually decrease to 60.25% for women by 2023. However, these reductions were largely offset by uprating past wages fully to average-wage growth through the elimination of the unfavourable adjustment discussed above. Moreover, this elimination improved transparency.

The 2012 reform was legislated as the Global Financial Crisis was exerting large public finance pressure. In contrast to previous reforms, it was introduced with a very short transition period while sharply limiting the grandfathering of past entitlements. Indeed, for those who had not reached the eligibility conditions by 2012, the new accrual rates were applied to the whole earnings histories. This change was particularly important for insurance periods prior to 2000, when the accrual rates were substantially higher.

However, the 2019 reform backtracked and eliminated any further decrease, freezing women’s total accruals at 63.50% after 40 years of insurance. In addition, the reform introduced a pension bonus for having children, at 1.36% accrual per child up to three children. This bonus does not apply if the retirement age condition is lowered based on childcare. The 2019 reform also increased men’s total accruals from 57.25% to 58.50% in 2020 and then gradually to the new women’s level of 63.50% by 2025.

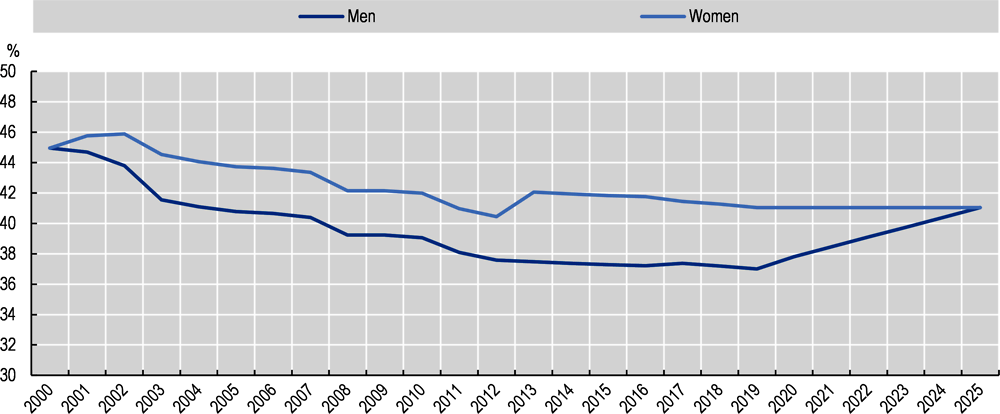

Figure 1.12 shows the joint effects of changes in accrual rates, in the uprating of past wages and in the gross-net wage coefficient on gross replacement rates. Both men and women who earned the average wage and retired in 2000 had a gross replacement rate of 45% after a full career of 40 and 35 years, respectively. Total accruals then diverged between men and women, while the adjustment to the uprating of past wages lowered the replacement rates further by 6% by 2003 and by 13% in 2012. Overall, for individuals retiring in 2012, the theoretical replacement rates decreased to 37.6% for men and 40.4% for women.

In 2013, the improved uprating of past wages almost fully offset the decrease in accrual rates for men. By contrast, the replacement rate for women rose to 42% as it is associated with an increase in the period to accrue the full pension from 38 to 40 years. Men’s replacement rates started to converge to women’s levels in 2019 as a result of the reform, reaching 41% in 2025.

The average newly granted pension recently declined for men, from 45% of the national average wage in 2013 to 41% in 2019 (Figure 1.13, Panel A), while extending the full-career condition for women from 38 to 40 years in 2012 has helped maintaining their new pensions at around 44% of the average wage. More generally, the decrease in the average effective insurance period for men and its increase for women (see below) have been central in the evolution of pension differences across genders.

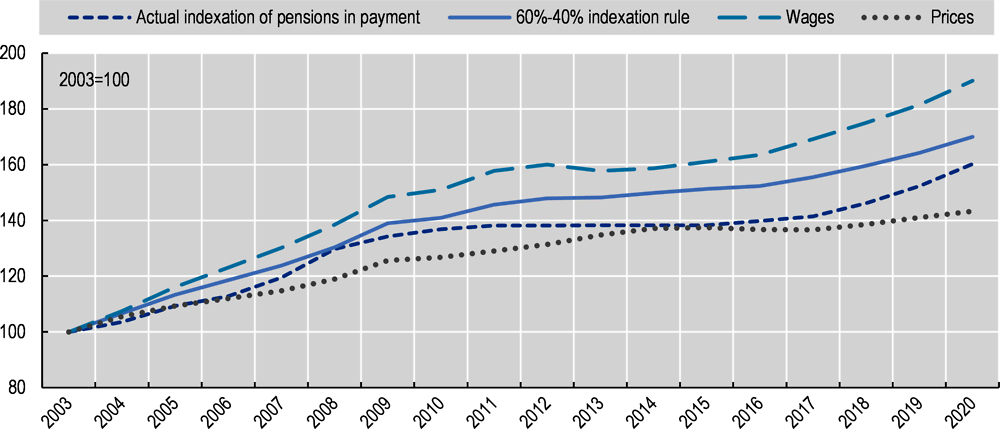

Between 1992 and 2012, benefits were indexed in relation to wage growth but with some complex albeit significant additional adjustment. This implied that the actual indexation was about 0.6 percentage points lower than wage growth per year on average (Majcen and Verbic, 2009[6]). The 2012 reform set pension indexation as a mix of 60% of wages and 40% of prices, which greatly improved transparency. Still, between 2012 and 2015 the benefits were not indexed at all as the fiscal situation was tight, but this was offset from 2020 by extraordinary pension indexations in 2019 and 2020.

Overall between 2000 and 2019, pensions thus did not keep pace with wages. The gross average wage increased by 39% in real terms against only 5% for gross average pension, with even a decline in real terms between 2009 and 2014. This led to a big fall in the average pension relative to the average wage from 51% to 39%, i.e. a drop of almost one-quarter (Figure 1.13, Panel B).

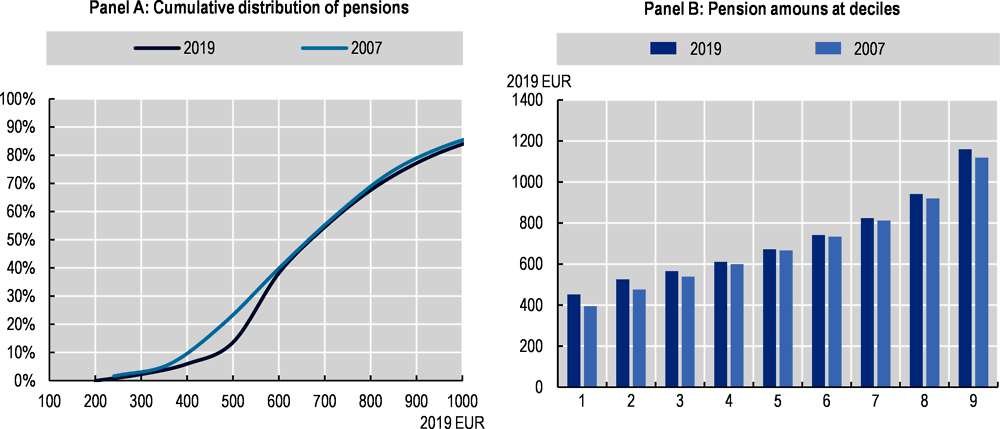

The distribution of pensions remained broadly stable in real terms for the upper half of pensions between 2007 and 2019 (Figure 1.14). However, the first deciles increased sharply partly due to the introduction of the guaranteed pension in 2017 (Chapter 3).

Flexibility of retirement and combining work with pension have been eased

When working after fulfilling eligibility conditions to an old age pension, there is no earnings cap nor earnings limit beyond which pension benefits are reduced. However, only part of the pension can be claimed when combined with work. The 2020 reform provided some improvement in the flexibility to combine work and pensions. Yet, when working full time, only 40% of the old-age pension can be claimed for the first three years and 20% thereafter. This implies a mandatory deferral of 60% and then 80% of the benefit when working. The same rules apply to people who re-join employment after having retired.

Between 2016 and 2020, the share of pension that could be combined with full-time work was only 20%, also applicable to those re-joining full-time employment. Between 2012 and 2016, the conditions were tighter and the 20% of pension was paid only until age 65 and only to those who have not reduced working hours after qualifying to pensions. The option was not available upon re-joining employment after having retired. Before 2012, it was possible to combine work and part of pensions only when working less than half time.

As of 2020, when working after meeting full eligibility conditions the annual accrual rate is increased from 1.36% to 3.00% for three years. Between 2013 and 2019 the additional accrual was 4.00%, but, as explained above, only 20% of pension could be claimed. Between 2000 and 2012, the accrual rates were set at 3.0%, 2.6%, 2.2% and 1.8% for the first through the fourth year of work beyond the eligibility conditions. Before 1999, the accrual rate beyond eligibility condition was in fact lower than the regular one, at 1% annually.

The share of new pensioners who combine work and pensions sharply increased from 7% to 36% between 2013 and 2018 and is likely to rise further as the part of the pension available to full-time workers increased from 20% to 40% in 2020 (Figure 1.15).9 Figure 1.15 shows that the number of newly granted benefits increased steadily from 18 241 to 23 791 between 2013 and 2018 while the number of non-working new pensioners declined from 17 071 to 15 906. This suggests that extended options of flexible retirement may have contributed to prolonging working lives.

Combining work and pensions in Slovenia is roughly actuarially neutral, as the inflated accrual rate of 3% actuarially compensates for the mandatory deferral of 60% of pensions when working. Such mandatory deferrals are complex and rather uncommon in OECD countries and combining work and pensions after the official retirement age is possible in all OECD countries – at least when pension eligibility conditions are met – although disincentives exist in several of them. By contrast to most defined benefit schemes in OECD countries, Slovenia does not provide any bonus for deferring pensions when not working. A more detailed analysis of combining work and pensions in Slovenia compared to the OECD countries is provided in Annex 1.A.

1.4.1. The normal retirement age will continue to lag well behind the OECD average

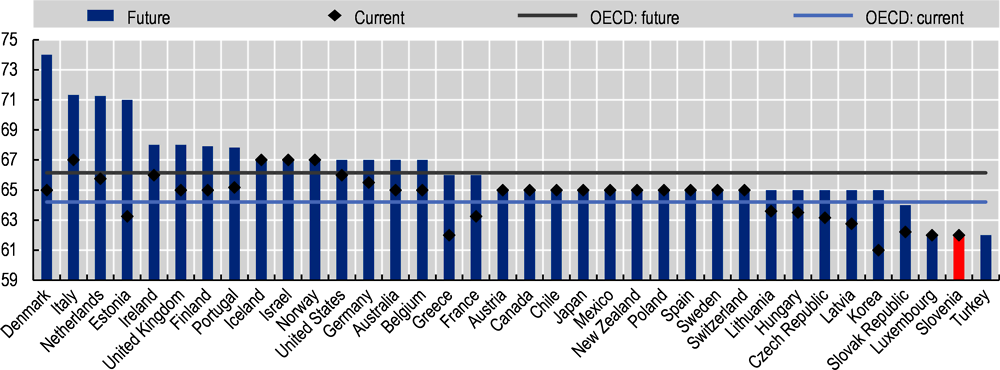

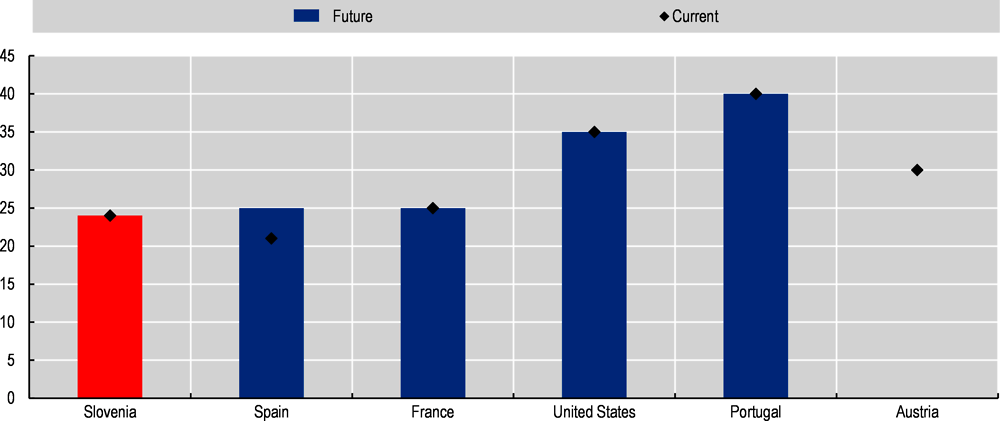

The OECD normal retirement age is defined as the age when you can start receiving a full pension without penalties after an uninterrupted career from age 22. The normal retirement age typically combines both the age and insurance period criteria. In 2018, the normal retirement age across OECD countries was equal to 64.2 years for men and 63.5 years for women on average among OECD countries (Figure 1.16). Only Greece, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Turkey had a normal retirement age below 63 years. Iceland, Norway, Italy and, for men only, Israel had the highest normal age of 67.

In 2018, women had different normal retirement ages than men in one-third of OECD countries. The largest gender difference was 5 years in Austria, Israel, and Poland. However, for the generation entering the labour market now, gender gaps are being phased out in all OECD countries except Hungary, Israel, Poland and Switzerland, and in Turkey for those starting the career in 2028. In Slovenia, the tightening of eligibility conditions since 1999 has not affected the normal retirement age for men entering the labour market at age 22, which has remained at 62 years, but has raised it for women from 57 to 62 years as the full contribution period increased from 35 to 40 years. The gender gap was eliminated in Slovenia in 2019.

The normal retirement age will increase in 20 OECD countries (Figure 1.16). For the generation entering the labour market in 2018, the average normal retirement age will raise to 66.1 years for men and 65.7 years for women based on current legislation, hence an increase of about 2 years. The future normal retirement age is below 65 years only in Luxembourg and Slovenia – the only countries where the retirement age is currently low and not projected to increase – as well as the Slovak Republic and Turkey.

Even with rising retirement ages, the time spent in retirement as a share of adult life is expected to increase in the vast majority of OECD countries (OECD, 2019[8]). Between the generations ending and starting their career in 2018, the remaining life expectancy at age 65 is projected to increase on average from 18.1 to 22.5 years for men and from 21.3 to 25.2 for women. This means that based on current legislations less than half of life expectancy gains would be passed on to increases in the normal retirement age. The share of adult life spent in retirement is 35% today and 39% in the future in Slovenia, among the highest levels in the OECD, which represent an increase of more than 10% in that share.10

1.4.2. Short contribution period to retire at age 60 without penalty

Along with Slovenia, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Spain provide options to retire without penalty before the statutory retirement age for those having contributed long enough in public earnings-related schemes (Table 1.2). In Germany and Portugal this option is only for those with very long careers of 45 and 48 years, respectively. Belgium and France require 42 and 41.5 years, respectively. In Greece, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Spain a worker can retire after a shorter contribution period of 40 years (or even 37 years in Spain), but in Greece this is possible only from age 62, and in Spain from age 65. Italy introduced Quota 100, a temporary scheme that allows retiring at age 62 with 38 years of contributions; it applied since 2019 and was supposed to expire in 2021 but it was prolonged for 2022 with a higher age condition of 64. Thus, Luxembourg and Slovenia stand out as countries where one can retire without a penalty at age 57 or 60 after a 40-year career. Hungary allows only women to retire after having contributed for 40 years without any age requirement.

Based on current legislation, these eligibility conditions will be tightened in most countries, but not in Slovenia. In France and Spain, the reference contribution period will be lengthened by 1.5 and 2 years, respectively. In Germany, Italy (except for Quota-100) and Portugal, which already apply a long reference period to retire early without penalty, the retirement-age condition will be tightened. The combined conditions will remain loose in Luxembourg and Slovenia, and for women in Hungary.

1.4.3. Low minimum retirement age

The large majority of countries had an early retirement age – the earliest age at which the receipt of a pension (potentially with penalties) is possible – for private-sector workers lower than the normal retirement age.11 The early retirement age was 61.2 years in 2018 on average among the 31 OECD countries that have a specific minimum retirement age for their mandatory earnings-related scheme (Figure 1.17). Tightening eligibility conditions for early retirement either by increasing the minimum retirement ages or by making early retirement more penalising has been one major pension policy trend over the last decades. Early retirement ages have been rising by a little over one year between 2004 and 2018.

In Slovenia, it is possible to retire at age 60 after a 35-year long career, provided that the insurance years missing to reach 40 years are purchased; in that case, benefits are subject to the penalties described in the Overview section above. When starting the career at age 22, a worker without career interruptions needs to purchase two years of insurance to be able to retire at age 60. Slovenia is among few OECD countries where private-sector workers can access their pensions at age 60 or below (Figure 1.17).12

1.4.4. Sharp increase from a low level in the effective age of claiming pensions

The average age of claiming pensions for the first time sharply increased by five years, from 57.5 to 62.5 for men between 1992 and 2019 (Figure 1.18). For women, the rise was even larger from a very low age of 52.7 years to 60.7 years. Hence, the gender gap more than halved during that period although women still retire about two years before men on average. This relates to the tightening of eligibility conditions for women through the whole period, while they did not change for men between 1999 and 2012. Since 2013, the effective age of claiming pension has increased significantly due to improvements in labour market conditions after the global financial crisis and following the 2012 pension reform, which tightened eligibility conditions and eased the possibility to combine work with pensions.

Despite these upward trends, many people still retire very early. As explained in Section 1.2.1, retirement-age conditions can be lowered based on having children, military service or having started the career before the age of 18. Half of women and one fourth of men started claiming their pension before age 60 in 2019 (Figure 1.19). Incentives to work longer when eligible to pensions before age 60 are poor. The age-related penalties for early retirement, i.e. based on the purchased period, are capped at age 60. Moreover, the accrual rate increases from 1.36% to 3% for working beyond 40 years only after age 60: before age 60 there is no bonus on deferring pensions and the 1.36% accrual rate provides little incentive (Annex 1.A). Retiring after age 65 – which requires a much shorter insurance period of 15 years – is uncommon among women: only 1 in 20 do so against almost 1 in 3 among men.

1.4.5. Lower average insurance period of new male retirees since 2006

The upward trend in the average insurance period of new retirees stopped around 2007 (Figure 1.20). With the global financial crisis, and perhaps due to the uncertainty around pension reforms, people then tended to retire with slightly shorter contribution periods. As a result, the average insurance period among new retirees declined from 38.3 to 37.3 years for men between 2006 and 2012, and from 36.0 to 34.9 years for women between 2008 and 2011.

After 2013, it fell further for men to 37 years in 2019, probably due to the increasing impact of less favourable employment records since the transformation in the early 1990s. For women, the upward trend resumed in 2012 and the average insurance period increased strongly to 39 years in 2019. By crediting periods of part-time work to one of the parents of children younger than four in the same way as full-time work, the 2012 reform has been a key determinant of this increase along with the impact of retiring later as shown in Figure 1.18. In 2019, among new retirees, about one-quarter of men and half of women retired at age 59 or earlier with an average qualifying period of around 40.5 years.

The increasing incidence of combining work and pensions might partially explain the recent decrease in the average insurance period among new male pensioners. The share of new pensioners combing work and pensions increased from 6% to 36% between 2013 and 2018. More than three-fifths of those combining work and pension work full time, which is called dual status, of whom 60% are men. When working full-time, only 40% of the pension is paid (20% before between 2013 and 2019), but the beneficiaries are not taken into account in the calculation of the published average insurance period of new pensioners; they are taken into account once pensioners claim the full benefit after having stopped working full-time. This might temporarily lower the average insurance period of new pensioners because the average insurance period of people in dual status was 39.8 years for both men and women in 2019, which is substantially more than among all new pensioners, at 37 and 39 years for men and women, respectively.

1.4.6. At the same ages, younger cohorts accumulated shorter insurance periods

Younger cohorts generally have shorter insurance periods at the same age (Figure 1.21). In 2009, men and women aged 50-54 had an average cumulative insurance period of 29.3 and 31.1 years, respectively, which decreased to 27.4 and 30 years in 2019 (Panel A). A similar pattern is visible also at younger ages (Panel B). Shorter insurance periods at given ages stem from younger cohorts having spent more time in education.13 Additionally, younger cohorts have been more exposed to unemployment risks after 1992. Younger cohorts will have to retire later to offset the impact on pension replacement rates.

1.4.7. Favourable unemployment protection for older workers might help early retirement

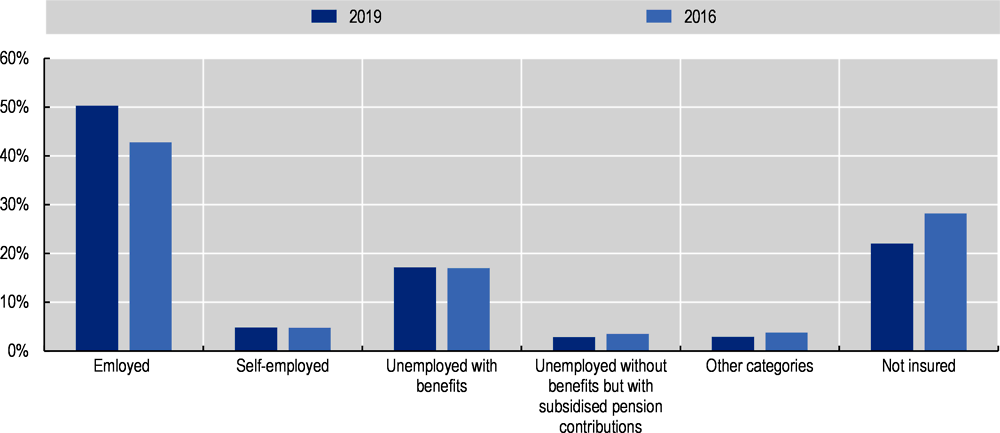

Many people are unemployed immediately before claiming pensions in Slovenia. Almost one in five new retirees were insured based on their unemployment status one month before claiming pensions in 2019 Figure 1.22.14 The more favourable unemployment protection of older workers contributes to this pattern. First, unemployment benefits are paid for 19 months when older than 53 years with at least 25 years of insurance, increasing to 25 months when older than 58 with 28 years of insurance. This compares with 12 months maximum for younger individuals. Second, when less than one year is missing to reach the pension eligibility conditions, pension contributions are subsidised by the state budget to bridge the gap and pension entitlements accrue accordingly. This contributes to explaining why in 2019 among the 55+ there were only 100 unemployed classified according to the ILO definition (i.e. actively searching for a job) out of 301 total registered unemployed against only 134 of registered unemployed aged 25-49.15

Moreover, Slovenia provides additional employment protection for older workers. A worker cannot be dismissed for economic reasons from age 58 until qualifying for an old-age pension, or during the five years just before fulfilling the qualifying period. This additional protection ceases when workers become eligible to old-age pensions or to unemployment benefits, and in that latter case until meeting the conditions for an old-age pension.16 In December 2020, the requirement to provide a justified reason when dismissing an employee who has met eligibility conditions to the old-age pension was removed, which effectively introduces a mandatory retirement age. However, the implementation of this amendment is uncertain as it has been appealed in the Constitutional Court on the ground of discrimination.17

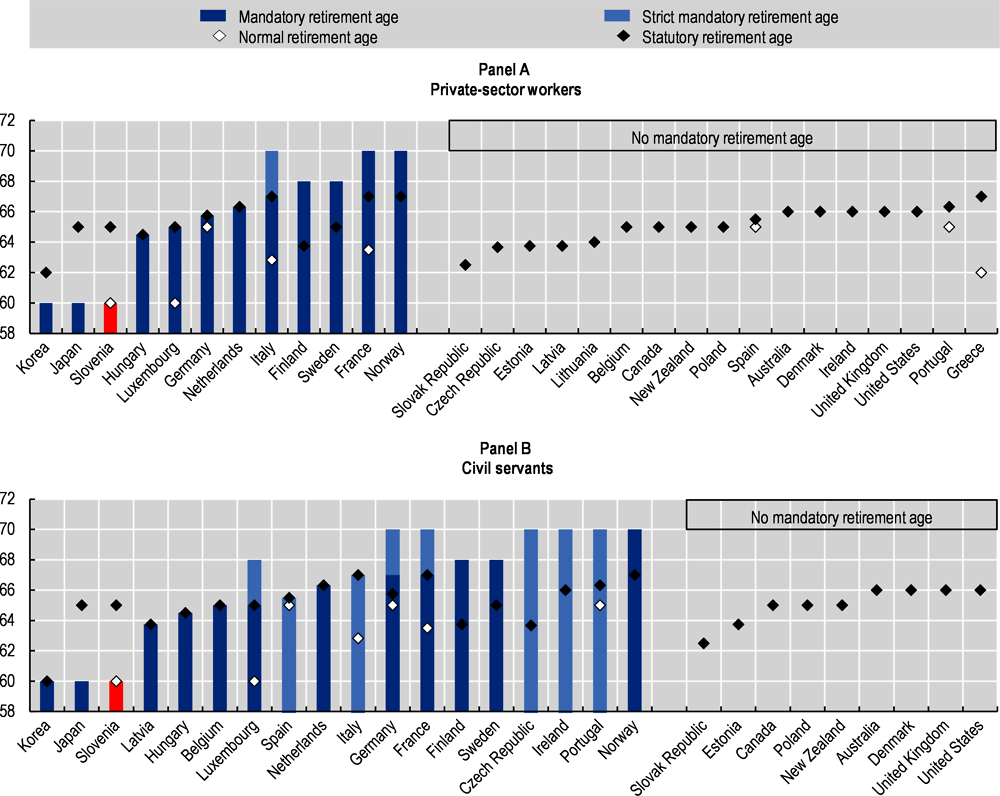

Annex 1.B provides a summary of mandatory retirement and pensions in OECD countries, with implications for Slovenia. The analytical part leads to three main findings:

More than half of OECD countries do not allow for mandatory retirement in the private sector. Nine OECD countries ban mandatory retirement even for civil servants.

Mandatory retirement practices have been reduced in a number of countries. With the exception of Slovenia since December 2020, no European country allows mandatory retirement before the statutory retirement age, except for specific occupations with health and safety concerns. Only a few European countries have some form of mandatory retirement in the private sector before the age of 68 years.

Mandatory retirement is sometimes advocated if seniority is an important component in wage setting or in the case of strict employment protection against individual dismissals. Slovenia scores below the OECD average in terms of both importance of seniority pay and strictness of employment protection.

In Slovenia, pension benefits are calculated from a defined benefit formula in which: the average annual accrual rate depends on the insurance period; the reference wage is based on net wages from the best consecutive 24 years; and there is a strong redistribution through the high level of the minimum reference wage.

1.5.1. The reference wage is based on only 24 years of earnings

Pension benefits in Slovenia are calculated by multiplying total accrual rates by the reference wage (also called the pension rating base). To calculate the reference wage, past wages are valorised with the average wage growth. Then the most favourable 24 consecutive years are averaged to calculate the reference wage. Only years in which contributions were paid for at least six months are included in the calculations. If, in a given calendar year, contributions were paid for a shorter period, the year is not taken into account and is replaced with the next available year (or years). This applies only to the reference wage calculation while the total accrual rate accounts for all months of insurance.18 As mentioned before, a floor at 76.5% of the net average wage applies to the reference wage, and a ceiling of 306% of the net average wage.

The large majority of OECD countries take into account wages throughout the whole career for calculating pension benefit. Recently, the Czech Republic, Greece and Norway joined this group (Boulhol, 2019[10]). Exceptions are Austria (which will use lifetime earnings for people born from 1955), France, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and the United States (Figure 1.23). France, Slovenia and Spain are the only countries using 25 years or less, although France was planning to use lifetime earnings, but the reform was suspended due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Using part of the career generates inequities as people with the same lifetime earnings and the same total contributions might have very different pensions. While taking into account only the best years protects against some forms of career incidents, it also generates perverse, regressive effects by favouring workers experiencing large wage improvements who tend to be high-wage earners, as the low-wage periods (typically at the beginning of the career) are ignored (Aubert and Duc, 2011[11]). In addition, men and women with longer career breaks, due to e.g. childcare, rarely enjoy strong career progression (OECD, 2017[12]) and therefore they do not benefit from the shorter period to calculate the reference wage.

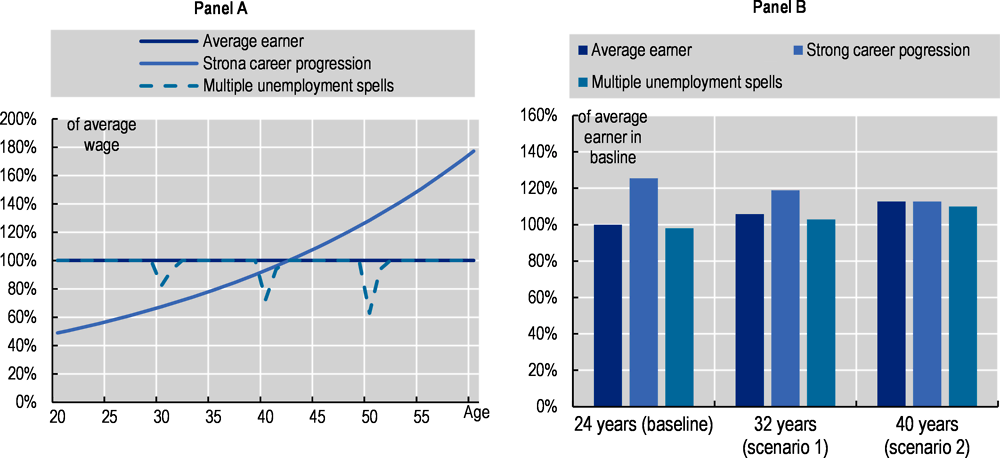

Figure 1.24, Panel A shows three career cases: one with stable earnings at the average wage throughout the career, one with a strong earnings progression: from 49% to 177% of average wage between ages 22 and 62, and one with average earnings when working but with the career affected by multiple unemployment periods covered by unemployment benefits. The wage parameters of the wage-progression case are calibrated such that the average wage over the whole career is equal to that of the stable-earnings case.

Under the current reference-wage calculation (baseline), the strong career progression leads to a 25% higher pension than the stable-earnings case although the lifetime earnings are the same (Figure 1.24, Panel B). Moreover, this reference wage calculation protects well against career breaks as the career-break case generates a pension that is only 2.0% lower compared to the uninterrupted career case.

The potential aggregate impact on pension expenditure of changing the reference period was analysed for Slovenia in 2010 (Čok, Sambt and Majcen, 2010[7]). The analysis based on individual earnings histories of people who retired in 2007-09 showed that increasing the reference period from 24 to 32 or 40 years while keeping other parameters constant would decrease average pensions by 5.4% or 11.2%, respectively.19 However, to better identify the mechanism at work with short reference periods, it is best to consider changing the length of the reference period in a budget-neutral way, meaning in such a way that total pension expenditure and the average pension are unaffected. Lowering pension spending might be needed, but this is a different objective that can be pursued by a range of instruments. One simple way to lengthen the reference period in a budget-neutral way consists of raising accrual rates. The following analysis is based on such reform scenarios.

Were the calculation of the reference wage prolonged to 32 years in a budget neutral way (scenario 1), the pension would increase by 5.7% in the stable-earnings case due to higher accrual rates (Figure 1.24, Panel B). The pension of the strong-career progression case would decrease by 5.0% while remaining substantially higher than that of the stable-career worker. In the case of multiple unemployment spells, the pension loss compared with the full-career case increases only very slightly to 2.7%.

Finally, were the calculation of the reference wage expanded to 40 years (scenario 2), i.e. to the full career of someone starting career at 22 and retiring at age 62, the pensions of the workers with uninterrupted careers but differing in the earnings profiles would equalise, being 12.6% higher than in the average earner pension under the current conditions (baseline). At the same time, the pension of the person with multiple unemployment spells is now 2.5% lower than the full-career case. This confirms that the current reference wage calculation strongly favours workers with strong career progression, who are likely to also have higher income, while extending the reference period does not penalise those with unemployment breaks.

Consistent with this, Čok, Sambt and Majcen (2010[7]) show that increasing the reference period would reduce pension inequalities. Indeed, such a reform while keeping the other parameters unchanged would not affect pensioners in the lowest quintile of pensions thanks to the effect of the minimum reference wage. The impact of increasing the period from 24 to 34 years would lower pension by about 6% for all higher quantiles. Hence, if such a reform is conducted in a budget neutral way, it could reduce old-age inequality without affecting average pension levels.

1.5.2. Gross pensions unusually accrue based on net wages

All OECD countries, except for Hungary and Slovenia, accrue pension entitlements based on gross wages. In Slovenia, the reference wage is expressed in approximately net terms because gross wages that enter in the calculation of the reference wage are multiplied by a coefficient, which is calculated from the tax and social security rate at average earnings and thereby fluctuates slightly every year. This coefficient (64.63% in 2019) means that at the average wage the reference wage is exactly equal to the net wage. Such a design makes gross pensions dependent on tax and social security rates.

Most pensioners do not pay income taxes. Pensions are taxed based on the progressive tax rates, which increase from 16% for low income (below 40% of annual average wage in 2019) to 50% (for income exceeding 350% of annual average wage). However, some tax allowances lower the taxable income. The general tax allowance amounts to EUR 3 500, i.e. 17% of annual average wage, and is granted to all taxpayers. This allowance is increased for people earning less than 63% of annual average wage, which results in no personal taxes being paid for income lower than 44% of annual average wage. On top, pensioners are granted an extra tax allowance of 13.5% of their pension, which additionally reduces the tax base. All this means that a single person receiving only pension would start paying the personal income tax when benefits exceed 120% of average pension or 46% of average wage. As a result, the average net pension was only 1% lower than the average gross pension in 2019.

This combination of pension accruals based on net wages and generous tax allowances for pensioners makes net pensions unduly complex. Any increase of personal income tax rates mechanically reduces gross replacement rates. It lowers net wages, and therefore gross pensions. Additionally, higher tax rates will reduce high net pensions further, having a double effect on pensions. On top, any increase of employees’ social security contribution rate will automatically reduce gross pension benefits. Both these effects might lead to unintended consequences of benefit deterioration following changes in tax or contribution rates. They also make the benefit calculation harder to understand for workers.

1.5.3. Strong redistribution through the minimum reference wage

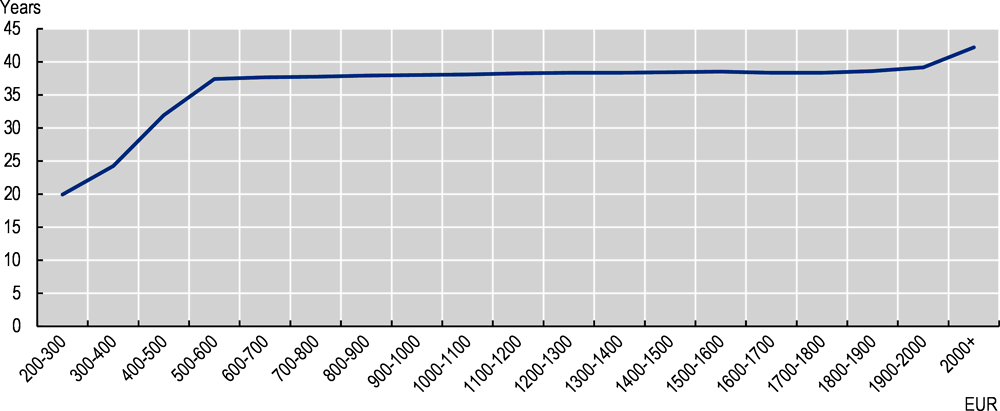

The minimum reference wage is set at 76.5% of the net average wage, providing a floor that benefits low earners. In 2021, the minimum reference wage was EUR 913 per month, compared with a reference wage based on the minimum wage of EUR 662. The minimum reference wage multiplied by total accruals leads to minimum pension benefits, which thus depend on the length of the insurance period. The redistributive effect of the minimum reference wage is slightly offset by the minimum base for contributions, which is set at 60% of the gross average wage, implying that the effective contribution rate is higher for workers close to the minimum wage, which was equal to 55% of the average wage in 2020. In addition, the maximum reference wage is set at EUR 3 651 per month, or 306% of net average wage; contributions continue to be paid on wages above that ceiling, but they do not bring additional pension entitlements.

The minimum reference wage plays an important and increasing role in Slovenia. The share of new pensions calculated with the minimum reference wage stood at 38% for women and 30% for men in 2019 compared to 32% and 17% in 2013, respectively. In 2021, the minimum pension after a 40-year career stood at EUR 580 (= 913*63.5%) for women and EUR 543 (= 913*59.5%) for men, which is topped up to EUR 620 through the guaranteed pension (Chapter 3).

Pensions are concentrated around levels corresponding to the minimum pension amount after a full career, and even more so for women than for men (Figure 1.25). The median pension was between EUR 600 and 700 in 2019. One in five men and one in four women received pension amounts between EUR 500 and 600. Only 5% of pensioners had pensions higher than EUR 1 500 and less than 1% had more than EUR 2000, which means that the maximum reference wage is effectively binding for only few workers: a 40-year career with net earnings equal to the maximum reference wage would result in a pension equal to EUR 2 213 (= 3 485 * 63.5%).

For those having pensions lower than EUR 300 the average contribution period is about 20 years while among those with a pension between EUR 500 and 600 the average contribution period is 37.4 years (Figure 1.26). For those with higher pensions the average contribution period is only slightly higher as for the recipients of pensions of between EUR 1 500 and 1 600 the average contribution period is 38.5 years. Thus, whatever the pension bracket, many retirees have a total insurance period of less than 40 years for a few reasons. First, women were entitled to the full pension with careers shorter than 40 years until 2017 whereas the option of early retirement after a 20-year career was closed for men in 2016 only and for women in 2020. Second, 38 years of pensionable service without purchase grant eligibility to the old-age pension from age 61 in case of having children, military service or having started the career before the age of 18. Third, those who have started working late or had long career breaks can retire with a much shorter insurance period of 15 years from age 65.

1.5.4. Effective accrual rate close to the OECD average

The effective accrual rate measures the rate at which benefit entitlements are effectively built for each year of contribution. For defined benefit (DB) schemes, it equals the nominal accrual rate adjusted to account for how pensionable earnings are defined (thresholds, valorisation of past earnings, sustainability factors). In defined contribution schemes (funded or notional) schemes the effective accrual rate depends on contribution rates, rates of returns and annuity factors.

Given the nominal accrual rates described above, the average annual nominal accrual rate for a 40-year career stands at 1.026% in Slovenia for women and 0.945% for men retiring now converging to 1.026% for both men and women entering the labour market now.20 When the annual allowance is included it gives an effective accrual rate of 1.045%, which is very close to the OECD average of 1.046% (Figure 1.27). Based on current legislation, the highest future effective annual accrual rates are in Austria (1.78%)21 while Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain and Turkey also have an average accrual rate that is larger than 1.6%.

1.5.5. Indexation of pensions in payment

Most OECD countries index pensions in payment to prices. Eight countries index benefits with a mix of price inflation and wage growth, four countries combine inflation and either GDP or wage bill growth. Norway and Sweden index pensions based on wage growth minus a fixed rate of 0.75% and 1.6%, respectively.22

Slovenia belongs to countries that index pensions to a mix of wages and prices, with weights of 60% and 40%, respectively.23 This indexation rule was introduced in 2012 while before indexation was linked to the changes in the average wage and in the average pension in a complicated way. Figure 1.28 shows that the actual indexation was close to the 60%-40% mix between 2003 and 2008 on average. Frozen indexation in 2012-15 resulted in the actual pension indexation being around 3 percentage points lower than implied by the 60%-40% rule in this period, but this was offset by the extraordinary indexation in 2019 and 2020. On average over 2003-20, nominal wages increased by 3.9% per year and consumer prices by 2.1% while the average annual pension indexation was 2.8%.

The real value of pensions should be protected to maintain standards of living, especially as retirees have very limited options to accommodate to lower income. This implies that pensions should be indexed at least to inflation. The indexation rule is the result of a political choice. For a level of total pension spending consistent with financial sustainability, there is a trade-off between lower pensions when retiring and more generous indexation, with the higher level of indexation benefiting the pensioners in the first part of their retirement period and the groups having lower life expectancies.

This section provides an assessment, based on the OECD pension model, of future replacement rates in international comparison, for dependent employees by earnings levels and for various career patterns, including the impact of career breaks due to unemployment and childcare.

1.6.1. Slightly higher net replacement rates than OECD average at the average wage…

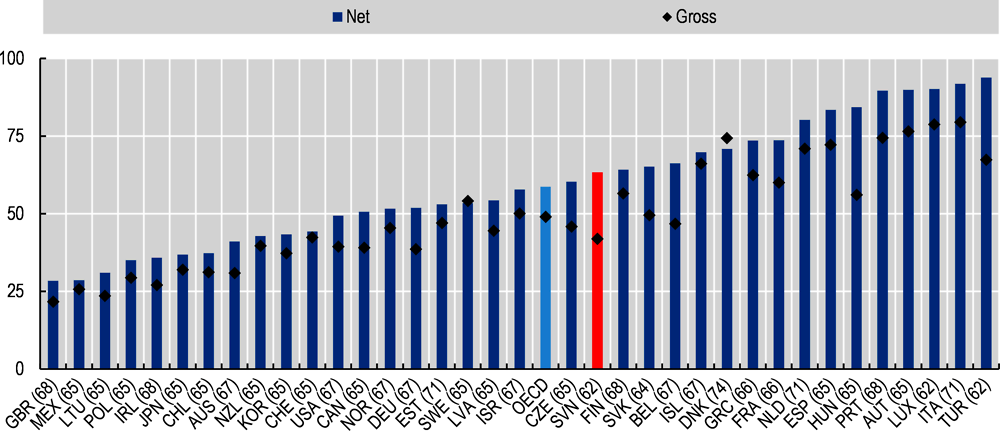

As a best case – full career from age 22 until the normal retirement age – illustrating what pension systems produce in a comparable way, the future net replacement rate from mandatory schemes for people entering the labour market now averages 59% in OECD countries at the average-wage level (Figure 1.29). In Slovenia, it is slightly higher at 63%.24 There is a substantial cross-country variation, from less than 30% for example in Lithuania to 90% or more in Austria, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal and Turkey. This compares to 60% and 64% for men and women retiring in 2021.

However, accounting for differences in life expectancy, retirement ages and indexation rules, the net pension wealth will be much larger in Slovenia than in the OECD on average even though replacement rates at retirement are similar. The net pension wealth measures the total discounted value of the lifetime flow of all retirement incomes in mandatory pension schemes at retirement age in number of years of net wages. It is a summary measure of total pensions that are expected to be paid throughout the retirement period. For average earners, net pension wealth for men is 10.6 years and for women 11.7 years of net average wages in the OECD on average. It is substantially higher in Slovenia at 13.6 and 15.2 years, respectively. This indicator varies from less than 6 years for both men and women in e.g. Lithuania to 21.4 years for men and 23.5 years for women in Luxembourg. For low earners, net pension wealth stands at 12.4 and 13.8 years for men and women on average among OECD countries while it is very high in Slovenia, about 8-to-9 years higher at 20.2 and 22.9 years for men and women, respectively, second only to Luxembourg.

For average earners, the net replacement rate is 10 percentage points higher than the gross replacement rate on average in the OECD due to the effect of progressive taxation and contributions paid by employees as well as favourable tax treatment of pensioners in some countries. The difference is over 30 percentage points in Hungary and Turkey and 15-20 percentage points in Belgium, Portugal and the Slovak Republic, and 21 percentage points in Slovenia. In Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Turkey, pension income is liable for neither taxes nor social security contributions, whilst in Belgium, Portugal and Slovenia pensioners are granted higher tax allowances than workers.

1.6.2. … while low earners with full careers benefit from high replacement rates

In most OECD countries, low earners benefit from progressive pension calculation or qualify for minimum pensions or targeted benefits. As a result, low earners often have higher replacement rates than average earners. Low-income workers at half the average wage would receive net replacement rates averaging 69% among OECD countries, compared with 59% for average-wage workers (Figure 1.30).

In Slovenia, the future net replacement rate for low earners is equal to 95%, much higher than the OECD average, and 25 percentage points above that for average earners. The minimum reference wage is the main driver of this pattern while progressive taxation of labour earnings also plays a role to some extent. This high replacement rate is similar to levels in Austria, the Czech Republic and Hungary. Denmark is at the top of the range with 105%. At the other extreme, Chile, Japan, Lithuania, Mexico and Poland offer net replacement rates below 50% to low-income earners, implying a very low pension even after a full career. As for high earners at twice the average wage, the net replacement rate is 51% on average in OECD countries, below the 59% figure for average earners. Replacement rates for these high earners are higher than 80% in Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Turkey, while at the other end of the spectrum, Ireland, Lithuania, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United Kingdom offer a replacement rate of less than 25% from mandatory schemes. In Slovenia, the high earners can expect a net replacement rate of 59%, which is slightly lower than for average earners, at 63%.

1.6.3. Prolonged unemployment spells require retiring later to avoid penalties

The full-career case is instructive for capturing the impact of key pension parameters, but falls short of being representative. Many individuals experience some periods of unemployment or enter relatively late in the labour market for example due to tertiary education. In terms of pension entitlements, most OECD countries aim to protect against at least some gaps in the employment record.

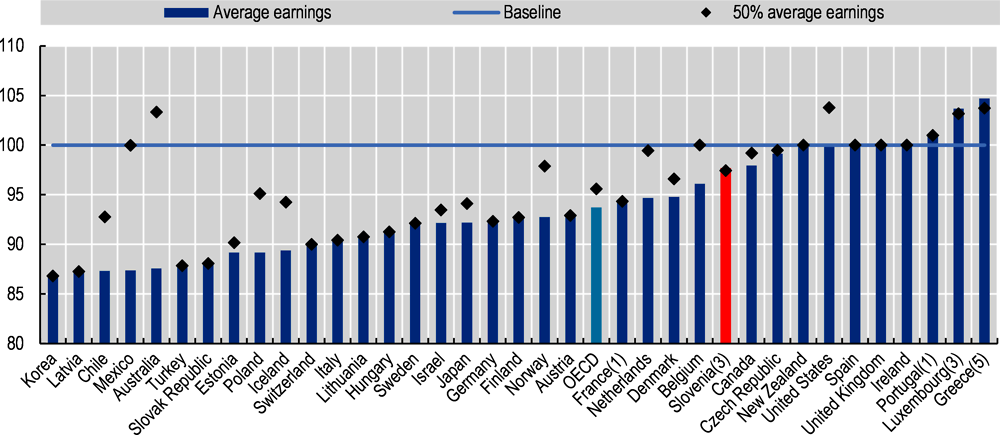

Average-wage workers with five years of unemployment will have a pension equal to 94% of that of a full-career worker on average across OECD countries, with substantial cross-country variation (Figure 1.31). In some countries, workers in this case will have to retire later than the normal retirement age to avoid pension penalties. This includes Greece, Luxembourg and Portugal, where workers in this situation have higher benefits than full-career workers. At the bottom of the range, Australia, Chile, Estonia, Korea, Mexico, the Slovak Republic and Turkey have limited pension protection against unemployment risks and the future benefit is equal to about 87% of that of a full-career worker.

In Slovenia, a five-year unemployment break in the middle of the career implies retiring at age 65 rather than at age 62 as is the case for full-career workers, and with lower pension. Pension entitlements accrue only in the first year of the unemployment spell based on unemployment benefits, which are equal to 80% of previous earnings in the first three months and 60% in the following nine months. Hence, the five-year break creates a four-year hole in pension accruals. When retiring without penalty is possible at age 65, the insurance period will still be one year shorter compared to the full-career case. As a result, despite retiring three years later, the five-year career break lowers pension benefits by 2.3% compared to the full-career case. In Slovenia, accruals lost during the career break similarly affect pensions of workers with average and low wages whereas many OECD countries provide better cushioning to low earners. However, low earners already benefit greatly from the effects of the minimum reference wage as explained before.

1.6.4. Pension credits cover part of childcare periods

Many individuals, often women, interrupt their career to care for children. Pension credits for childcare typically cover career breaks until children reach a certain age. They are generally less generous for longer breaks and for older children. Many OECD countries credit time spent caring for very young children (usually up to 3 or 4 years old) as insured periods and consider it as paid employment for pension purposes. In addition, Hungary, Italy, the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic currently relax pension eligibility conditions based on having children; the last two countries in this list will eliminate these relaxations.25

Figure 1.32 shows the case of average-wage female workers taking a five-year career break to care for two children. In that case, the future pension is equal to 96% of the full-career case on average across OECD countries, under the strong assumption that these women resume their career at the same wage level as those who continued to work (Figure 1.32). The pension level is not affected by such a career break in nine countries including the Czech Republic and Hungary. At the other extreme, average-wage women caring for children during five years will have a pension at least 10% lower in Australia, Chile, Iceland, Latvia and Mexico.

With the childcare break, Greece and Slovenia require that women retire later than the normal retirement age – five years in Greece, two years in Slovenia – to avoid benefit penalties. As a result, benefits are projected to be 5% higher than for the full-career worker in Greece. In Slovenia, maternity and parental leaves accrue pension entitlements in the first year of a child’s life at the level of 100% of previous earnings up to a ceiling.26 Additionally, provided the woman fulfils the full-retirement condition when retiring, she then receives a pension bonus equivalent to one-year accrual for each child (of up to three). Thus, while career breaks for childcare may affect the reference wage, their impact on pensions goes mainly through any lost accruals for part of the breaks.27

In Slovenia, a woman who enters paid employment at age 22 and takes five years out of work to care for two children will have been insured for 37 years at age 62 (37 years = 40 years – break of 5 years + 2 years covered). The earliest age at which she can retire without penalty is 63 years and 8 months with 39 years of insurance as the retirement age at 65 can be lowered by 16 months for having cared for two children.28 In that case, these two additional years will accrue pension entitlements if she works, but she will not receive the bonus for childcare. She will end up with a benefit being 1.2% lower than in the case of a woman born the same year retiring at age 62 with 40 years of insurance once pension indexation is taken into account. An alternative that is not shown in Figure 1.32 is for her to retire at age 65, when she will benefit from the pension bonus equivalent to 2 years of insurance. Her pension will then be 5.8% higher compared to the full career case and 7.1% higher than in the case of retiring at 64 after the childcare period.

1.6.5. Pensions are higher for civil servants thanks to an additional funded scheme

Slovenia, along with ten other OECD countries including Austria, Denmark and Norway, has a top-up mandatory component for civil servants above and beyond the mandatory scheme that exist for private sector workers. Only Belgium, Germany, France and Korea have an entirely separate scheme for civil servants. About two-thirds of OECD countries have no special scheme for civil servants, all employees being covered under the same mandatory schemes, at least for new labour market entrants, or they offer benefits similar to those for private-sector workers based on technically separate schemes, the difference lying mainly in the administration of the schemes.

In Slovenia, the top-up component for civil servants consists of a separate occupational defined contribution scheme. The employer (ultimately the state) pays additional contributions to the occupational scheme at the most common flat rate of EUR 30.53 a month in 2020,29 valorised with the average-wage growth of civil servants, while employees do not pay any contributions. At the national average wage, EUR 30.53 adds 1.7 percentage points to the regular contribution rate of 24.35% to the universal scheme. Following standard assumptions in the OECD pension modelling for funded defined contribution schemes,30 a civil servant retiring in 2060 after earning the average wage for a full career can expect to have a gross pension that is 11% higher than a private sector employee with the same earnings. While significant, this 11% difference is relatively small compared with other countries having a top-up or totally different schemes, especially relative to Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. A separate analysis of supplementary pension schemes provides more information about this scheme.

1.7.1. Same total contribution rates as for employees in Slovenia

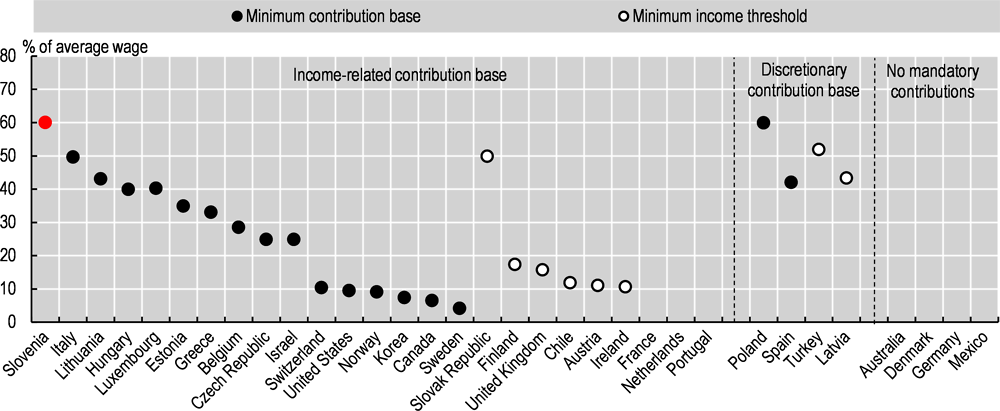

The pension coverage of the self-employed varies considerably across OECD countries although most require the self-employed to participate in earnings-related pension schemes. In 18 countries, self-employed workers are mandatorily covered by earnings-related schemes, but the pension coverage is limited as they are allowed to contribute less than employees through reduced contribution rates, a high degree of discretion in setting their income base often resulting in only minimum contributions being paid, or minimum income thresholds below which they are exempt from contribution obligations.

In half of the countries including Slovenia, mandatory contribution rates are aligned between dependent workers and the self-employed: the self-employed pay a contribution rate that corresponds to the total contribution rate of employees, i.e. the sum of employee and employer contributions, which is equal to 24.35% in Slovenia. Beyond Slovenia, this includes Canada, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Turkey and the United States. Among them, the self-employed contribute based on income in only ten OECD countries, including Slovenia. However, even there, insufficient compliance with pension rules may undermine pension coverage (OECD, 2019[2]). In the other countries with earmarked pension contributions, contribution rates are lower for the self-employed.

1.7.2. Less contributions paid and less entitlements accruing due to base effects

Even when nominal contribution rates are the same for dependent employees and self-employed workers, pension contributions can differ substantially because the contribution base, i.e. the earnings reference to calculate contributions, is not identical. For employees, pension contributions are usually paid on gross wages, which are equal to total labour costs minus the employer part of social security contributions. For the self-employed, there is no genuine equivalent of gross wages.

Most countries use some income-related measure as the contribution base for the self-employed. Depending on the country, this measure is income either before or after deducting social security contributions. A number of countries apply the contribution rate to a fraction of gross income, e.g. 50% in the Czech Republic, 67% in the Slovak Republic, 75% in Slovenia and 90% in Lithuania.

In Slovenia, the calculation of the contribution base of the self-employed results in less pension contributions and less pension entitlements compared to employees with similar earnings net of social security contributions. The contribution base for a self-employed person is equal to previous year’s profit before taxes increased with social security contributions and multiplied by 75%. For dependent workers, the total contribution rate of 38.2% is split between 22.1% paid by employees and 16.1% by employers.

For an income of 100 after paying social contributions and before tax, the contribution base for employees is equal to the gross wage, i.e. to 100 / (100% – 22.1%) = 128.37 with pension contributions of 31.26 (11.36 paid by employeyers and 19.90 by employees). For the self-employed with the same income of 100 after paying social contribution and before tax (assuming the same profits as the previous year), the contribution base is equal to 100 / (1 – 75%*38.2%) * 75% = 105.12, with pension contributions paid of 25.60. Hence, the self-employed pay about 18% less contributions and accrue less pension entitlements when having the same declared income before tax as employees.31 To fully align the contribution bases with employees, the 75% coefficient used to calculate contribution base of the self-employed workers would need to increase to 86%.

Self-employed workers with a taxable income equal to the net average wage before tax can expect to receive in the future – after contributing what is mandatory during a full career – an old-age pension equal to 79% of the theoretical gross pension of the average-wage worker in the OECD on average (Figure 1.33). In Slovenia, taking also into account past references for profits, the reduced contribution base results in lower pensions from mandatory earnings-related schemes, at 86%, of that of employees with the same taxable earnings. Much lower theoretical relative pensions for the self-employed – between 40% and 60% of employees’ pensions – are estimated in Poland, Spain and Turkey where only flat-rate contributions to earnings-related schemes are mandatory for the self-employed, and in Latvia, where mandatory contributions above the minimum wage are reduced substantially.

1.7.3. Very high minimum contribution base

Most countries set minimum income thresholds and/or minimum contribution bases. Minimum income thresholds are minimum levels of income below which the self-employed are exempt from regular mandatory pension or social security contributions; in that case, they do not accrue regular pension entitlements either. These thresholds exist in eight OECD countries, but not in Slovenia, ranging from 11% of the average wage in Ireland to around 50% in the Slovak Republic and Turkey.

Minimum contribution bases are minimum amounts to which pension or social security contributions for the self-employed apply, even if true income is lower. They prevent the self-employed from contributing very low amounts, but they also imply that the effective contribution rate might be high for individuals earning less than the threshold.

In Slovenia, the contribution base cannot be lower than 60% of the average wage, which is the highest level across OECD countries (Figure 1.34). Only Poland has the same value, but it allows the self-employed to lower their contributions for a limited period if their revenue is low. Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, Spain and Turkey set the minimum contribution base around 40%-50% of average wage, while other countries set it lower. France, the Netherlands and Portugal set neither minimum contribution base nor minimum income threshold.

The gross (taxable) profit for the self-employed is determined by deducting costs from revenues for a given calendar year. There are two ways to account for costs in Slovenia. The first is to use actual costs. Alternatively, the self-employed can choose to use a flat-rate cost regime that sets profits at 20% of revenues. This option is available to the sole self-employed having revenues below EUR 50 000, or below EUR 100 000 if employing any workers. Similar flat-rate cost deductions to calculate the contribution rate exist in the Czech Republic and Portugal.

Pension contributions are mandatory for the self-employed unless they are also insured as employees. In December 2019, among those who paid contributions based on self-employment income, 47 037 self-employed were registered under the actual cost regime and 26 714 under the flat-rate regime. Additionally, there were 9 504 and 21 773 self-employed registered under the actual and flat-rate regimes, respectively, who did not contribute towards pensions from their self-employed income as they were insured also as employees. The self-employed choosing the flat-rate regime operate in sectors where costs are rather low: legal/accounting jobs, arts, IT and communication, and manufacturing (OECD, 2018[13]). The actual cost regime is chosen by the self-employed who operate in the sectors with higher costs: construction, wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing, legal/accounting jobs, transportation, and accommodation and food. The number of self-employed in the flat-rate regime more than tripled since 2014.

Given the high minimum contribution base and the possibility to opt for the flat-rate cost regime, almost 70% of the self-employed paid pension contributions from the minimum base in 2016 (Stropnik, Majcen and Rupel, 2017[14]). In Poland, the Slovak Republic and Spain, 70% or more of the self-employed also pay only compulsory minimum pension contributions (Spasova et al., 2017[15]).

The 2018 OECD Tax Policy Review of Slovenia suggested that the minimum contributions base should be abolished or equal to the minimum wage of full-time employees, which was equal to 50% of average wage,32 to be better aligned with the rules applying to full-time employees and to prevent creating cash-flow problems for the self-employed with variable income (OECD, 2018[13]). This OECD Review also suggested that the 20% revenues used for profits in the flat-rate regime could be increased substantially to better reflect the actual costs of the self-employed.

References

[19] AGE Platform Europe (2009), 2009 AGE Statement on Pensions: Ensuring adequate pensions for all in the EU - a shared responsibility for society.

[11] Aubert, P. and C. Duc (2011), “Les conséquences des profils individuels des revenus”, Economie et Statistique, Vol. 441-442, https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1377523?sommaire=1377529.

[10] Boulhol, H. (2019), “Objectives and challenges in the implementation of a universal pension system in France”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1553, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5a476f15-en.

[7] Čok, M., J. Sambt and B. Majcen (2010), Impact assessments of the proposed pension legislation, University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Economics.