Chapter 3. Finding the right balance in the use of conditional grants

Discussions on the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations often revolve around the premise that intergovernmental grants – especially earmarked grants – should be minimised. It is also often argued that intergovernmental grants imply a vertical fiscal imbalance between central and subnational governments. These arguments are based on the “benefit principle”, and emphasise the importance of establishing a clear linkage between expenditure and revenue decisions of subnational governments. But in reality, almost all local governments worldwide provide, at least to some extent, essential (redistributive) public services such as health, education, and social services, which require substantial revenues. The four country cases examined in this chapter show the importance of intergovernmental relations in the role of co-ordinating across levels of government for the efficient and equitable provision of essential public services. They also show that, in many countries, earmarked grants play an important role in the provision of these services.

In countries where the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations is evolving, the size and composition of local revenue are often subject to controversial debates.1 As Wildasin (2004, p. 268[1]) notes, this is not the case of mature federations where “the institutions of federalism function relatively effectively, are relatively stable, and have developed over long historical periods.” On the other hand, in countries where the history of decentralisation is relatively short, as in many developing countries and in some European countries such as Spain and Italy where fiscal decentralisation is still an ongoing process, the institutions of intergovernmental fiscal relations are not stable and changing them have significant political and economic implications. Among various issues regarding the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations, the most controversial ones are those related to the division of tax bases and revenues between central and subnational governments and the related choice between general grants and conditional grants (e.g. earmarked grants).2

Regarding these two issues, it is worth noting that the European Charter of Local Self-Government takes a very clear position: Article 9 of the European Charter stipulates that: 1) local authorities should have adequate fiscal resources of their own; and 2) transfers to subnational governments should be in the form of general-purpose grants (grants without conditionalities).3,4 With its clear criteria on the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations, the European Charter provides an important guideline for European countries, as well as for those outside Europe, on policy discussions on the design of fiscal decentralisation.

In the policy debates that take place in many countries, it is indeed often observed that discussions on desirable properties of the composition of local revenue are based on a simple premise: local taxes are more desirable than general grants, and general grants are more desirable than conditional grants. However, this is a simplistic approach to the design of the structure of local revenue because it prevents proper recognition of the role of general and conditional grants. Moreover, so-called “local taxes” in many countries, in fact, do not represent local taxing power. For example, the revenues from personal income tax, corporate income tax, and value-added tax (VAT) in Germany are shared among levels of government by the rules stipulated in the German Basic Law (constitution). As discussed in, among others, McLure (2001[2]), Watts and Hobson (2000[3]) and Rodden (2002[4]), tax sharing or revenue sharing (tax sharing with horizontal redistribution) is a form of intergovernmental grant because local governments do not control the shared taxes at the margin. Indeed, as illustrated by Blöchliger and Petzold (2009[5]), the dividing line between tax sharing and grants is not very clear.

The fact that tax sharing and grants are similar in their nature has an important implication: the simplistic preference of local taxes over grants as a source of local revenue can mislead policy discussions on how to design the structure of local revenue. In particular, the main reason why local taxes are preferred to intergovernmental transfers as a source of local revenue is because of “transfer dependency” created by the latter: it softens local governments’ budget constraint and weakens their fiscal accountability. However, since tax sharing and intergovernmental grants are similar in nature, the same is true for tax-sharing arrangements, as discussed in, among others, Rodden (2003[6]) and Stehn and Fedelino (2012[7]). While both tax sharing and intergovernmental grants share the problem of transfer dependency, the equalisation effect of tax sharing is not necessarily better than that of intergovernmental grants, because the main objective of the former is not fiscal equalisation across jurisdictions. Therefore, from both efficiency and equity points of view, it is not clear whether local taxes are better than intergovernmental grants as a source of local revenue if “local taxes” are shared taxes.

In the same vein of local taxes and shared taxes, a simple premise that general grants are better than earmarked grants as a source of local revenue is not helpful in practice since both general grants and earmarked grants have their own merits and demerits in terms of efficiency and equity of fiscal resource allocation. In the case of health care, for example, many countries in Europe and elsewhere rely on a scheme of earmarked grants in one way or another. The same is also true for education. For example, the central government in England switched in 2006 from general grants to earmarked (ring-fenced) grants as a means of supporting schools.

Italy pushed for fiscal federalism with the constitutional reform in 2001 and sought to give regional and local governments greater fiscal autonomy with respect to revenue and expenditures. A noticeable aspect of the 2001 Italian constitution is that it introduced the concept of “essential level of services” for important public services such as health and education for which the central government calculates the standard cost corresponding to the essential level. In order to meet the requirement to guarantee the essential level of health and education, the Italian government has introduced a system of earmarked grants.5 Thus, even after Italy pushed for fiscal decentralisation, the role of earmarked grants became, in a sense, even stronger depending on the nature of public services.

Korea is another case where earmarked grants play an important role in supporting essential public services. Elementary and secondary education in Korea, arguably the most successful policy of Korea, has long been strongly supported by the central government with a system of categorical block grants (earmarked grants). The Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) pushed for a large-scale fiscal reform in the early 1990s and consolidated many specific grants into a system of general grants. However, the amount of specific grants has steadily increased since the 1990s in these countries and is not negligible compared to that of general grants. A more detailed discussion on this is found in the section “Country cases”.

In sum, when so-called local taxes are actually shared taxes, as in the case for many countries in Europe, Asia and Latin America, a simplistic premise (such as inferred from the European Charter) in designing the structure of local revenue needs careful consideration. In particular, the soft budget constraint problem pertains not only to intergovernmental grants but also to so-called local taxes in many countries. Similarly, as to the choice between general grants and earmarked grants as a desirable source of local revenue, a simplistic answer is not readily available. In this regard, Smart and Bird (2010[8]) note that “the limited role of matching grants to address spillovers from the Pigouvian perspective explains neither the number and importance of earmarked grants nor the changes observed over time in different countries in the importance of earmarking. Nor does it explain the extensive use of categorical block grants and closed-ended matching grants which do not as a rule affect spending choices directly, as the Pigouvian argument requires.” Therefore, as Oates (2008[9]) emphasises, what needs to be focused on in the debates on intergovernmental fiscal relations is its “design and operation” in a country-specific policy environment rather than the application of simple rules.6

Among OECD countries, the case of the United States stands out in its overwhelming use of conditional or earmarked grants in transfers from the federal government, precisely the opposite of the premise of the European Charter. On the one hand, US evidence shows that conditions have been crucial in attaining the sought-after policy results when other instruments proved insufficient, such as with interstate transportation regulations. On the other hand, numerous conditions have proved very difficult, most recently with education performance conditions for underperforming schools.

Additionally, although the European Union does not fit neatly into the fiscal federalism literature, its experience as a supra-national entity making conditional grants to national and subnational governments is relevant. Through its structural funding and reform support programmes, the European Commission seeks to enhance local capacity as well as promote national governments’ structural reforms (Berkowitz, 2017[10]; OECD, 2018[11]; Dolls et al., 2019[12]). While the evidence on the grants’ success remains controversial, the European Commission’s role in making direct fiscal transfers is an important additional government actor to consider when addressing the design of grants.

In the next section, two prominent issues regarding intergovernmental fiscal relations will be discussed. First, the relationship between the size of subnational debt and the degree of local government autonomy (or the degree of fiscal decentralisation) will be examined. As previously discussed, it is often argued that the soft budget constraint problem is expected to occur more in countries where local governments are less independent and rely more on the central government’s financial support. However, among OECD countries, federal countries where subnational governments are supposed to be more independent than those in unitary countries tend to have more serious subnational debt problems. This implies that the role of intergovernmental relations (a broader issue of institutions and political system) plays a critical role in the determination of subnational debt in comparison to the structure of local revenues (such as the size of local tax revenue or the degree of transfer dependency).

In the third section, the often-confused concepts of vertical fiscal gap (VFG) and vertical fiscal imbalance (VFI) are discussed. In much of the literature on fiscal decentralisation, the level of the VFG (intergovernmental transfers plus local borrowing) is often the metric that measures subnational revenue inadequacy. However, as recently discussed by Boadway and Eyraud (2018[13]), the VFG is a descriptive measure and does not in itself have any policy implications. On the other hand, the VFI refers to subnational revenue inadequacy, which causes such problems as inadequate public services, wasteful spending, persistent subnational debt, etc. However, as in the case of subnational debt, what is important to note in the case of the VFI is that it is created for various reasons that are in turn a function of the institutions of intergovernmental relations. In particular, almost every country has its own unique situation (via their constitution, laws, political system, informal traditions, etc.) that gives rise to the causes of VFI. Because of the complicated nature of the VFI, simply emphasising the importance of “own source local revenue” is often impractical and even counter-productive. In this regard, Watts’s observation is worth noting: “Different combinations of interacting factors tend to require their own distinctive processes for adjusting intergovernmental financial relations. Technical, financial solutions that do not take account of how they interact with the social, economic, political and constitutional context have therefore, in practice, tended to be counter-productive.” (Watts, 2000, p. 372[14]).

From a theoretical point of view, the reason why there is not a clear dividing line between different sources of local revenue, as well as the reason why the role of intergovernmental relations is an important factor in determining the level of subnational debt and the VFI is that, in many countries, local taxes are not local taxes in the sense of Tiebout (1956[15]), while the division of responsibilities among different levels of government is not consistent with the “decentralisation theorem” of Oates (1972[16]).

Regarding this point, Bird and Slack (2014, p. 43[17]) observe that “if one aim of policy is to ensure that the public sector operates efficiently, it is important to establish as clear a linkage between expenditure and revenue decisions as possible – to strengthen what Breton (1996[18]) calls the “Wicksellian Connection”.7 Having emphasised the importance of establishing the sound principle of local public finance implied by the models of Tiebout (1956[15]) and Oates (1972[16]), Bird and Slack then note that “theory and practice are far apart” (Bird and Slack, 2014, p. 45[17]). They further note that “in reality, decisions on the two sides of the local budget are usually made independently, often with relatively little local input, while both local expenditures and taxes often being largely determined by central authorities” (Bird and Slack, 2014[17]).

A key reason why the principle of the Wicksellian Connection does not hold in the area of local public finance is that, in many countries (both developed and developing), redistributive – “essential” as expressed in the Italian constitution – public services such as health, education, and social services are delivered by subnational governments. In this regard, the amount of revenue required to provide these redistributive services is much higher than that required for the types of local public goods considered by Tiebout (such as roads, parks, sewers, etc.). Given that there is a clear limit for “benefit taxes” to raise the significant amount of revenue required for redistributive public services (especially health and education), it is not surprising that, in many countries, shared taxes and intergovernmental transfers are an important source of subnational revenue. Recently, Boadway and Tremblay (2012[19]) reassessed the relevance of the Tiebout model as the theoretical framework used to explain the structure of local public finance, and made the following observation:

In the Tiebout–Musgrave–Oates tradition, expenditure assignment was based on the principle that state governments should be responsible for state public goods, and revenue assignment was based on the benefit principle. ... When we observe the reality of state fiscal structures – and local ones in unitary nations as well – these ideals are far from observed. While state governments do provide state public goods, by far their most important programs in most federations consist of quasi-private goods, social insurance and targeted transfers, including education, care for the elderly and children, health care, welfare and social services, and sometimes unemployment insurance. These programs are largely redistributive in nature. (Boadway and Tremblay, 2012, p. 1071[19])

If we accept the premise that “subnational government expenditure-tax systems are an important part of the redistributive and social insurance fabric of the public sector”, as Boadway and Tremblay (2012[19]) argue, what needs to be focused on in addressing the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations is not just the role of central-local fiscal arrangements, but also broader issues such as the political economy aspects of intergovernmental fiscal relations, and the role of co-ordination and co-operation among levels of government. These two issues are, of course, related. In their recent study of intergovernmental fiscal co-operation (IFC), Ter-Minassian and de Mello (2016[20]) emphasise that the effectiveness of IFC is affected by “economic, socio-political, and institutional factors, including constitutional provisions and power balances among different levels of government.” In the same vein, Boadway and Tremblay (2012, p. 1077[19]) observe that “government decision making is inherently complex, involving political, historical and institutional factors.” This view is easily confirmed when observing the impact of intergovernmental relations on the structure of local public finance in OECD countries.

In the fourth section of this chapter, how the system of intergovernmental transfers in selected countries evolves as per each country’s political, historical and institutional factors will be examined. This will allow us to appreciate the importance of country-specific approaches to the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations and the importance of intergovernmental fiscal co-operation.

As will be discussed in the next section, there is no clear theoretical reason why the role of intergovernmental transfers per se has to be negatively related to fiscal performance, such as the subnational debt level. This is because, in many unitary countries, the subnational debt level is tightly controlled by the central government. Yet many empirical studies find that there is a negative relationship between intergovernmental grants and fiscal performance. For example, Eyraud and Lusinyan (2013[21]) use the concept of “vertical fiscal imbalance” (VFI) as a measure of the gap between subnational governments’ own revenue and spending, which is by definition intergovernmental transfers plus borrowing. Eyraud and Lusinyan’s hypothesis is that large VFIs may relax fiscal discipline because “a common view in the normative literature is that a high reliance on intergovernmental transfers or borrowing ‘softens’ the budget constraint of subnational governments” (Eyraud and Lusinyan, 2013[21]). Using a sample of 28 OECD countries over 1969–2007, Eyraud and Lusinyan find that there is a statistically negative correlation between the VFI and fiscal performance (the primary balance of the general government). In another International Monetary Fund (IMF) study on vertical fiscal imbalances, Aldasoro and Seiferling (2014[22]) test whether deficit effect found by Eyraud and Lusinyan (2013[21]) will persist over time and translate into a higher level of general government debt. This study argues that, in the literature on fiscal federalism [such as Boadway and Tremblay (2006[23]) and Oates (2006[24])], VFI is identified as “transfer dependency”.8 They adopt the same definition of VFI as in Eyraud and Lusinyan (2013[21]) and find a statistically significant relationship between the levels of VFI and general government debt.

Besides these studies, there are many other studies on the effect of VFI (“transfer dependency”) on economic and fiscal performance. Karpowicz (2012[25]) conducts country case studies on the institutional changes that induced a decline in the VFI – again defined as the share of subnational own spending not financed through own revenues – and finds that a declining VFI generally – not necessarily significantly – coincided with improved fiscal performance in countries such as Belgium, Italy, Norway and Spain. In an empirical study on the relationship between vertical fiscal imbalance and regional disparities, Bartolini, Stossberg and Blöchliger (2016[26]) find that the VFI is associated with larger regional disparities. In an early empirical study on the vertical fiscal imbalance, Rodden (2002[4]) defines VFI as “transfers as a percent of total subnational revenue” and finds that more transfer-dependent subnational sectors are likely to run larger long-term deficits. Another early study on the VFI, Rodden, Eskeland and Litvack (2003[27]), provides in-depth discussions of both theoretical and empirical aspects of the VFI. This study explains the problem of transfer dependency (VFI) by noting that “systems of transfers and revenue sharing cause inefficient responses that are not foreseen in textbooks”, and that “transfer-dependent governments face weak incentives to be fiscally responsible, since it is more rewarding to position themselves for a bailout” (p. 14[27]). This negative assessment of intergovernmental transfers is also confirmed by Oates (2008[9]) in his discussion of second-generation fiscal federalism literature: “a kind of ‘transfer dependency’ can easily foster expectations of expanded central assistance in times of fiscal distress” (p. 320[9]). It is worth noting, however, that although Oates offers a negative assessment of transfers in line with second-generation fiscal federalism literature, he also emphasises that there are roles for intergovernmental transfers and therefore what is most important is “the design and operation” of systems of intergovernmental grants (Oates, 2008, p. 326[9]).

While it is true that intergovernmental grants can create transfer dependency, the literature surveyed above does not pay enough attention to the actual institutions (e.g. constitutions, laws and fiscal rules) of intergovernmental fiscal relations under which intergovernmental transfers operate. For example, tax sharing found in many OECD member countries and non-member economies (Austria, Belgium, Germany and many other countries in Eastern Europe, Asia, and Latin America) is from a theoretical point of view (but not by government accounting standard), a type of intergovernmental transfer. This is, in fact, recognised in Eyraud and Lusinyan (2013[21]). They note that tax sharing should be excluded from the calculation of “own taxes” and admit that not doing so (due to data unavailability) is the paper’s main shortcoming. From this point of view, it is worth noting that, in the study on the effect of local taxing power on government size, Rodden (2003, p. 718[28]) finds that, among 18 OECD countries used for the empirical analysis, only three highly decentralised federations – Canada, Switzerland and the United States – show non-negligible local taxing power. Obviously, it is too much of a simplification to assume that all the other 15 OECD countries with a high level of transfers or tax sharing are likely to suffer from the problem of transfer dependency.

In fact, contrary to the usual assumption of the literature on transfer dependency, the data of subnational debt shows that the subnational debt problem is confined to a few highly decentralised countries. Among the top four countries with a high level of subnational debt – Canada (67.2% of GDP), Germany (26.9% of GDP), Japan (34.0% of GDP), Spain (31.8% of GDP), and the United States (31.4% of GDP)9 – four countries (Canada, Japan, Spain and the United States) are highly decentralised countries that have relatively low levels of transfers (VFI) among OECD countries. A particularly noteworthy case is Canada. According to the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) of Canada, its subnational debt is not sustainable in the long run (PBO, 2018[29]). On the other hand, many countries that rely on a high level of intergovernmental transfers or tax sharing show very low levels of local debt (usually less than 5% of GDP).

As previously discussed, in many OECD countries, a large amount of intergovernmental transfers or tax sharing is employed as a source of subnational revenue. The fact that subnational governments rely on common fiscal resources also implies that constitutions and laws in those countries make it possible for strong intergovernmental fiscal co-ordination mechanisms to exist. Therefore, it is easier for the central government in these countries to impose an effective fiscal rule (such as a balanced-budget rule or a debt brake rule) on subnational governments in order to constrain subnational deficit or debt. On the other hand, in highly decentralised countries such as Canada, Switzerland and the United States, the strong independent power of subnational governments makes it difficult for central government to impose a robust fiscal rule on state governments.

A similar situation exists in Spain. After a long period of fiscal devolution, regional governments in Spain are now responsible for their own budgets, with limited intervention from central governments in regional governments’ fiscal behaviour. The level of subnational debt in Spain surged after the economic crisis in 2009 but has stabilised recently with the central government’s intervention to control government debt at both the central and regional levels.

These episodes indicate that subnational debt is likely to be more of a problem in highly decentralised countries where subnational governments are responsible for a large share of national tax revenue rather than in countries where central government has a relatively stronger institutional influence on both fiscal resources and fiscal behaviour of subnational governments. Of course, subnational governments in a highly decentralised country can voluntarily impose fiscal rules on themselves, as in the case of Switzerland, as discussed by Kirchgässner (2013, p. 142[30]). However, judging from the level of subnational debts in OECD countries (see Figure 3.2, later in this chapter), the problem of high subnational debt is more likely to occur in countries where subnational governments enjoy a high level of own local taxes and independent fiscal power than in countries with a high level of transfers or tax sharing, which is usually subject to intergovernmental co-ordination by constitutions and laws.

The concepts of the vertical fiscal gap (VFG) and vertical fiscal imbalance (VFI) are often confused, as discussed by Boadway (2004[31]; 2005[32]) and Sharma (2012[33]). More specifically, the term VFI is often used as the measurement of transfer dependency and used interchangeably with the size of intergovernmental transfers.10 For example, Eyraud and Lusinyan (2013[21]) and Aldasoro and Seiferling (2014[22]) both do not differentiate the concept of VFG and VFI and argue that the size of intergovernmental transfers, or the share of intergovernmental transfers in total local revenue, measures the extent of transfer dependency. However, Boadway (2004[31]; 2005[32]) argues that it is helpful to distinguish the need for intergovernmental transfers and the problems created by inadequate central-subnational fiscal arrangement.11 After all, there are theoretical and practical reasons for the existence of intergovernmental grants. At the same time, intergovernmental grants operate in an imperfect environment.

In a recent paper that attempts to clarify the concepts of VFG and VFI, Boadway and Eyraud (2018[13]) define vertical fiscal gap as “the financing structure of the decentralised system, and, more specifically, the degree to which subnational governments rely on their own revenues to finance their spending responsibilities.” On the concept of VFG, Boadway and Eyraud further note that “the fiscal federalism literature refers to this shortfall of subnational own-revenues relative to subnational spending as a ‘vertical fiscal gap,’ a term that is meant to be descriptive rather than pejorative” (Boadway and Eyraud, 2018[13]). On the other hand, a vertical fiscal imbalance is associated with a normative assessment and is defined as the situation in which “transfers to subnational authorities combined with their own revenues (and borrowing) are insufficient to finance their expenditure responsibilities.”

According to these definitions, the level of intergovernmental transfers (VFG), which are derived based on the concepts of efficiency and equity of resource allocation, is not a sign of inappropriate intergovernmental fiscal relations. Rather the problems of intergovernmental fiscal relations arise when its design and operation are neither efficient nor equitable. In other words, according to the definition of Boadway, the “vertical fiscal imbalance” describes the situation where the VFG is not adequately addressed in the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations. Although the consequences of the VFI are to be borne by both central and subnational governments, Boadway and Eyraud (2018[13]) focus on the fiscal behaviour of subnational governments and suggest that the problems associated with the VFI can be assessed based on a scoreboard of indicators such as inadequate public services, wasteful spending, persistent deficits of subnational governments, etc.

As Boadway and Eyraud (2018[13]) argue, the two concepts of the vertical fiscal gap and the vertical fiscal imbalance provide a useful and simple conceptual framework for identifying key challenges in the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations. Yet what is not explicitly discussed in Boadway and Eyraud (2018[13]) is that the concepts of VFG and VFI need to be understood in a much broader context. More specifically, in almost all countries - both developed and developing - legal and fiscal institutions (e.g. constitutions, law, fiscal rules, etc.) as well as political economy considerations are closely intertwined with the vertical fiscal gap and vertical fiscal imbalance. In this context, every country has its own unique situation, as can be inferred from the above-mentioned cases of Canada, Spain and Switzerland, and also from the country case studies of Karpowicz (2012[25]).

A different but related issue to the importance of the relationship between institutions and VFG/VFI is the heterogeneity of the composition of general government revenue and expenditures across different countries. In many OECD countries, social security funds (for health and old age pension) are a separate sub-sector of the general government. However, there are countries where social security funds do not exist as a separate sub-sector of the general government. A notable example is Canada, where health care is the responsibility of subnational governments. The share of subnational tax revenue in total national tax revenue in Canada is among the highest in the OECD, and yet state governments in Canada are burdened with the highest government debt levels. Obviously, the level of subnational own tax revenue or the size of intergovernmental transfers does not show the whole picture of intergovernmental fiscal relations of a country unless the dynamics of expenditure assignment – very often country-specific – are also understood.

A key implication of these observations is that understanding institutional adjustment and evolution in relation to the vertical fiscal gap, and the vertical fiscal imbalance is as important as the measurement and metrics of the VFG and VFI. As another example, it took almost 20 years to transform the regional income tax (“ceded tax”) in Spain from a kind of tax sharing (intergovernmental transfer) into an “own tax” of regional government. The central government of Spain ceded part of the income tax to regional governments in the early 1990s, but only in 2009 did central government abolish “default” tax rates of the regional income tax so that regional governments had to proactively decide on the level of tax rates of the regional income tax. This means that, although OECD Revenue Statistics shows that the size of own tax revenue of regional governments in Spain has significantly increased since the 1990s, the level of intergovernmental transfers in Spain had remained high – from a theoretical viewpoint – until 2009 when a real reform of intergovernmental fiscal relations took place.

In sum, in conducting comparative cross-country analysis on intergovernmental fiscal relations, it is important to understand the nature of country-specific institutions of VFG and VFI. This can be done in principle by including institutional characteristics variables in the regression analysis. Nevertheless, it is often elusive and challenging for regression analysis alone to fully account for the intricate and evolving nature of institutional characteristics of intergovernmental fiscal relations. If policy makers in a country are interested in drawing policy implications on its intergovernmental fiscal relations from comparative cross-country analysis, it is necessary and desirable to have an in-depth, country-specific understanding of why and how different countries adapt their institutions of intergovernmental fiscal relations to the changing policy environment they face.

United States

As is well known in the local public finance literature, the United States does not have a system of general grants or tax sharing.12 On the other hand, the federal government provides a wide range of specific-purpose grants to states and municipalities to financially support these governments. Therefore, the United States takes a position opposite to that of the European Charter with regard to the balance between general grants and earmarked grants [see Kim, Lotz and Mau (2010[34])].

The federal grants in the United States can be categorised broadly into two types: categorical grants and block grants. Categorical grants restrict funding to a narrow purpose (specific programmes or activities) and can be awarded either by formula or through a competitive application process. Medicaid, the National Highway Performance Program, the Children's Health Insurance Program are among the largest categorical grants. Block grants are allocated on a formula basis, are provided to a broad set of goals, and allow states and localities broad discretion in how they will meet those goals. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the Surface Transportation Program, and the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) are among the largest block grants. There are almost 1 400 federal grants as of 2018, which grew from 653 in 2000 (Edwards, 2019, p. 2[35]).

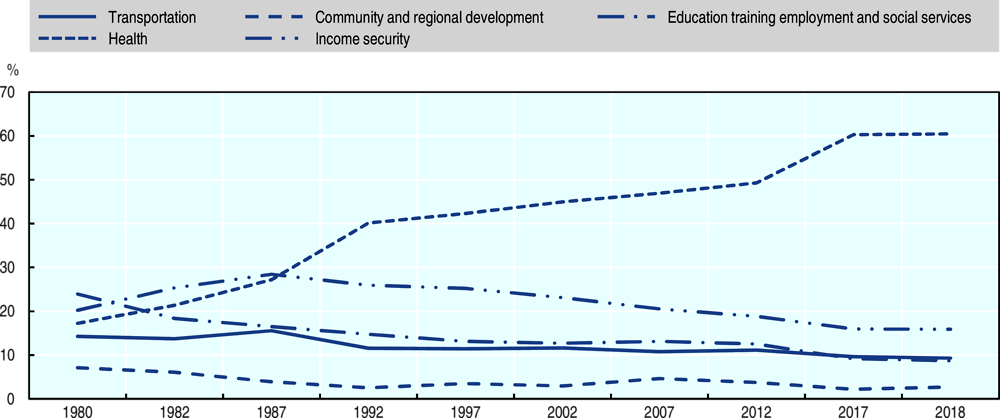

The total amount of federal grants to states and municipalities in the United States was about USD 700 billion in 2018 (Office of Management and Budget, n.d.[36]). Among the various types of federal grants, grants for health care are by far the largest, occupying as much as 60% (USD 421 billion) of total grants. Income security (USD 110 billion), transportation (USD 64.8 billion) and education (USD 60.6 billion) are the next largest areas. The amount of intergovernmental grants in the United States provided for redistributive services (health, income security and education) is almost 88% of total intergovernmental grants (Figure 3.1).

The structure of the US federal grants therefore confirms the previous discussion that the main purpose of intergovernmental grants is not to expand expenditures on local public goods that create spillover effects but to serve as a mechanism to effectively provide redistributive services such as health and education. Another point worth noting is the interaction between the system of intergovernmental grants and the institutions of intergovernmental relations such as mandates and legal constraints on subnational expenditures. This is documented in detail in Baicker, Clemens and Singhal (2012[37]). Their main finding is summarised in the abstract as follows:

We argue that the greater role of states cannot be easily explained by changes in Tiebout forces of fiscal competition, such as mobility and voting patterns, and are not accounted for by demographic or income trends. Rather, we demonstrate that much of the growth in state budgets has been driven by changes in intergovernmental interactions. Restricted federal grants to states have increased, and federal policy and legal constraints have also mandated or heavily incentivised state own-source spending, particularly in the areas of education, health and public welfare. These outside pressures moderate the forces of fiscal competition and must be taken into account when assessing the implications of observed revenue and spending patterns.

United Kingdom

Among OECD countries, the United Kingdom is one of the most fiscally centralised countries. According to OECD Revenue Statistics, the UK share of subnational tax revenue in total tax revenue is 4.9%. This is among the lowest levels in the OECD, along with the Netherlands (3.0%) and Austria (4.6%). As can be seen in Table 3.1, in some federal countries (such as Canada, Germany, Switzerland and the United States), the subnational tax share is higher than 30%. For Australia, Spain, and three Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Sweden), it is above 20%. The United Kingdom has begun an ambitious reform to devolve certain taxes to its regions, in phases. If UK regions were considered to be subnational (contrary to national accounts definitions), the announced measures could eventually double the subnational revenue share, on a weighted basis.13 Nevertheless, compared to other OECD countries, the subnational tax share in the United Kingdom remains very low.

Another aspect of local government finance in the United Kingdom is that the role of general-purpose grants is negligible. As can be seen in Table 3.2, the share of general-purpose grants (Revenue Support Grants) in total local government revenue in England is 0.66% of the 2019 budget. On the other hand, the share of specific grants in the local government revenue is 41%. Among the many specific grants provided by the central government in England, the specific grant for education – Dedicated Schools Grant (DSG) – is by far the largest, with its share close to 29%. The specific grant for police is the next largest at 7.5%.

It should be noted that the currently low share of general grants in local government revenue in England is the result of the education finance reform that took place in 2006. As Table 3.3 shows, the share of general grants in local government revenue in England was about 42% (GBP 26.6 million out of total GBP 63.8 million) in 2005-06, much higher than the current level. Since the 2006-07 budget, however, the central government’s support for local education changed from the system of general-purpose grants to a “ring-fenced” grant (Dedicated Schools Grant). This substantially reduced the size of general grants and increased that of specific grants in England.

The evolution of local government finance in England shows that how to provide essential redistributive services is a key determinant of the structure of England’s local government revenue. According to a document from the House of Commons Library (Jarrett, 2013[41]), which describes the background of introducing the Dedicated Schools Grant, the primary motivation for introducing earmarked education grants was the perceived failure of the school funding system before the introduction of the DSG. Before the introduction of the DSG, the Schools Formula Spending Share (SFSS) was part of a general-purpose grant (RSG) and was pooled with other public services (e.g. social services, roads) supported by RSG. In other words, local governments were free to decide how much of the general grant would be spent on education. In 2003, complaints from schools about funding shortages became a big political issue in England, and the then Secretary of State for Education promised to introduce “ring-fenced” or “dedicated” school funding. According to the White Paper that proposed the introduction of the DSG, the then Department for Education and Skills announced that “Local Authorities will not be able to divert this spending for other purposes [because of ring-fencing]” (Jarrett, 2013, p. 4[41]). As in the case of the United States, the evolution of local government finance in England also confirms that it is important to understand the importance of redistributive public services in affecting the structure of intergovernmental fiscal relations.

Canada

Canada is one of the most fiscally decentralised countries in the world. The share of subnational tax revenue in Canada is above 50%, which is the highest among OECD countries (Table 3.1). However, the size of subnational debt in Canada is also the highest among OECD countries. As seen in Figure 3.2, the size of subnational debt in federal/regional countries (Belgium, Germany, Spain, Switzerland, United States) and in some unitary countries (Japan, Norway) is relatively large. The size of subnational debt as a share of central government debt in Canada stands out.

The reason why subnational governments in Canada have accumulated such a large amount of debt is due to their high level of expenditure responsibilities. As seen in Figure 3.1, the share of subnational expenditure in Canada is by far the highest among OECD countries, at close to 75%. The vertical fiscal gap, which is about 25% of total subnational expenditure, is filled by three types of intergovernmental transfers: The Canada Health Transfer (CHT), the Canada Social Transfer (CST), and the Equalisation and Territorial Formula Financing. The CHT is an earmarked grant for health and is the second-largest federal budget item (about CAD 38. 6 billion in the 2018 budget), behind elderly benefits. The CST is a transfer to provinces in support of social services, early childhood development and post-secondary education. It was about CAD 14 billion in the 2018 budget. The amount of equalisation transfers was about CAD 19 billion.14 While CHT is an earmarked grant for health, CST is a block grant that is distributed to provinces on a per capita cash basis.

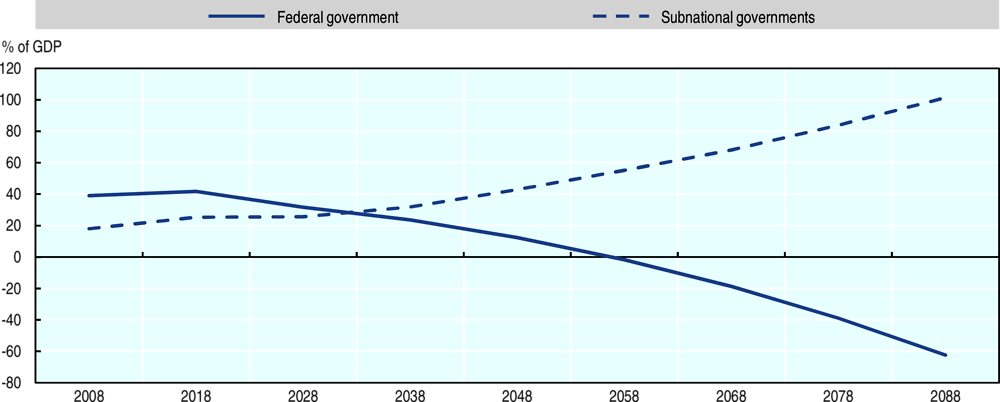

Although the federal government in Canada provides a sizable amount of transfers to subnational governments – close to 22% of the federal budget in 2018 – subnational governments in Canada are still accumulating a large amount of debt. In fact, according to the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) of Canada, subnational governments’ net debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to continuously rise to the point of unsustainability. This is in sharp contrast with the federal government fiscal situation, which is expected to continuously improve (Figure 3.3).

The large size of vertical fiscal gap and the contrasting fiscal situations of the federal government and subnational governments in Canada indicate that it is possible that the vertical fiscal gap is not adequately filled. Discussing the policy issues of the vertical fiscal gap and the vertical fiscal imbalance in Canada, Boadway (2004, p. 7[31]) remarks that “a VFI exists if the level of transfers is not consistent with the division of revenue raising, given expenditure responsibilities” and recommends that “the imbalance that exists between the federal government and the provinces should be addressed by an increase in transfers from the federal government to the provinces” (Boadway, 2004, p. 14[31]).

Boadway’s recommendation dates back to 2004 but his view seems even more relevant now. As seen in Figure 3.3, the subnational net debt in Canada has been around 20-30% of GDP for the past decade but is forecast to steadily increase over the coming decades and reach almost 60% of GDP around 2050. The Canadian PBO indeed predicts that “for the subnational government sector as a whole, current fiscal policy is not sustainable over the long term” (PBO, 2018, p. 25[29]).

The main reason why the PBO of Canada forecasts an increasingly large subnational debt is two-fold. As in many other countries, the ageing process is putting increasing cost pressures on health care. In addition, according to the diagnosis of the Canadian PBO, the federal CHT contributions to provincial and territorial health care spending declines significantly over time since the federal CHT envelope is limited to growth in nominal GDP.

According to the Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance (2006[43]), this situation was predicted a decade ago. At that time, the Advisory Panel forecast that health care spending would increase to 52.6% of provincial revenues in 2024-25 compared to 37.0% in 2005-06, due to ageing and a growing population, and higher inflation rates for health care costs (Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance, 2006, p. 64[43]). To avoid the fiscal unsustainability of subnational debt, the Advisory Panel recommended measures such as a more transparent system of intergovernmental grants, an increase in the amount of CHT and CST, and greater stability of CST transfer arrangements. However, it is worth noting that the Advisory Panel put a much stronger emphasis on the importance of intergovernmental process:

Above and beyond the equalisation program, or federal fiscal transfers to the provinces, or the territorial financing arrangements for Canada’s three territories, there is an issue that is even more important for the long-term health of the federation – namely, the intergovernmental process by which these matters are decided. (Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance, 2006, p. 89[43])

In addition, although it should be borne in mind that the Advisory Panel represents the view of the Council of the Federation, its criticism of the intergovernmental relations in Canada is rather harsh: “It is the Panel’s view that there is a flaw in the design of the Canadian federal system that this country’s governments should take steps to correct. At its core, we have a governance problem: the institutions and processes we use to manage the fiscal arrangements of the Canadian federation are inadequate to the task, and they are a good deal weaker than those of almost every other modern federation in the world.”

The challenges of intergovernmental fiscal relations Canada is faced with demonstrating that, as in the case of the United States and the United Kingdom, the provision of essential public services such as health, education and social services is a key obstacle in the design of intergovernmental fiscal relations. The case of Canada is particularly interesting because its subnational tax share is the largest among OECD countries, and its subnational debt burden is also the greatest. The size of earmarked grants in Canada also increased significantly in 2004 when Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST) was split into an earmarked grant for health (CHT) and a block grant for education and social expenditure (CST) (as mentioned above). According to the Department of Finance Canada, the motivation for creating an earmarked health grant was to improve accountability and transparency for federal health funding.15 As in the case of the Dedicated Schools Grants in England, the importance of earmarked grants has recently increased in Canada as well.

In sum, the combination of the high subnational tax share and subnational debt in Canada indicates that a high level of subnational tax share does not necessarily imply a high level of fiscal decentralisation, in the sense that subnational governments enjoy a high level of fiscal autonomy (i.e. independent decision making on subnational expenditures and corresponding subnational tax burden). Despite the high level of fiscal decentralisation, subnational governments in Canada are accumulating a large amount of debt, and the reason for this is that they are responsible for key redistributive public services such as health, education and social services. In turn, the reason why subnational governments in Canada are responsible for these key public services is political (constitutional), historical and institutional. Therefore, there is a clear limitation in finding the answers to the challenges of vertical fiscal imbalances in Canada through the Tiebout–Musgrave–Oates framework.

Sweden

Sweden is one of the most fiscally decentralised countries in the OECD. As shown in Table 3.1, the share of local tax revenue in Sweden is 35.4%, the highest among unitary OECD countries. Even among federal OECD countries, it is the third highest, following Canada (50%) and Switzerland (39. 6%). On the expenditure side, the local expenditure share in Sweden is around 50% (Figure 3.4). As of 2018, total local revenue (i.e. the total revenue of municipalities and county councils) was SEK 1.122 billion, which consists of operating revenue (SEK 228 billion), tax revenue (SEK 724 billion), economic equalisation and general grants from central government (SEK 154 billion), and financial revenue (SEK 17 billion).16 Therefore the shares of local taxes, grants, financial revenue, and operating income in total local revenue were, respectively, 64.5%, 14%, 1.5%, and 20%.17

Statistics Sweden does not publish the amount of specific grants received by local governments. According to alternative sources, general grants accounted for 12% of local revenue, and specific grants around 7%, as of 2014 (SKL International, 2014, p. 50[44]). These figures imply that the share of general grants in total grants is roughly 65%. Thus, compared to the United States, England and Canada, general grants in Sweden play a more important role than specific grants.

Given the fact that local taxes are the most important source of local government revenue, and intergovernmental grants are given in the form of general grants, it seems natural to argue that Sweden is one of the most fiscally decentralised countries, with strong local government fiscal autonomy. However, this interpretation should be made with caution. In particular, fiscal decentralisation in Sweden hardly fits into the Tiebout–Musgrave–Oates framework. There are two main reasons for this. First, from a constitutional point of view, Sweden is a unitary country, and all power rests in the central government.

Moreover, the Instrument of Government (the Swedish Constitution) stipulates that the principles of local self-government are laid down in law, e.g. enacted in the Parliament. With a large amount of fiscal resources provided by the central government, local governments in Sweden provide redistributive public services such as health, education, and social services, which account for more than 75% of local government expenditure there.18 Yet under the constitutional rule, “a range of acts and regulations such as the Social Services Act, the Planning and Building Act, the Education Act and the Health and Medical Services Act set out the specific functions along with detailed regulations that local authorities must follow in exercising their responsibilities” (SKL International, 2014[44]). Thus, the large local expenditures in Sweden are not the result of the autonomous decision making of local governments. This is certainly not the role of local governments investigated in the tradition of Tiebout–Musgrave–Oates models.

Another aspect of intergovernmental fiscal relations in Sweden is the evolution of the intergovernmental grants system. When Sweden was struck by the economic crisis in the early 1990s, it pursued significant economic and fiscal reforms. One reform was to consolidate many specific grants. According to Dahlberg (2010[45]), the earmarked grants made up about 20% of the municipalities’ total revenues, and the corresponding figure for general grants was less than 5% between 1965 and 1992. However, specific grants were consolidated in a system of general grants in the 1993 fiscal reform. The result was a dramatic shift in the ratio of general and specific grants, as shown in Figure 3.5. This can be interpreted to follow the recommendation of the Article 9 of the EU Charter: “Transfers to subnational governments should be in the form of general-purpose grants.” However, it should also be noted that the reform of the intergovernmental grants system in 1993 was accompanied by a dramatic reduction of total grants to local governments. As can be seen in Figure 3.5, total intergovernmental grants accounted for about 25% of local government revenue before 1993. However, it was reduced to around 20% in 1993 at the same time that the consolidation of specific grants took place. By 2003, the total amount of intergovernmental grants was reduced to 15% of local government revenue – a 10 percentage point decrease in local revenue in 10 years.

The history of the intergovernmental grants reform in Sweden in the 1990s provides another example of the importance of understanding the institutional background of intergovernmental fiscal relations. Given that local governments in Sweden provide redistributive public services regulated by central government’s laws and regulations, it cannot be simply said that the primary purpose of the consolidation of specific grants into a general grant system in Sweden was to enhance fiscal autonomy itself. After all, the constitution of Sweden clearly stipulates that local governments must follow laws (enacted by the central government) in exercising their responsibilities. Therefore, the shift of the balance between specific grants and general grants in Sweden after the 1993 reform has to be interpreted as the enhancement of local autonomy to meet the fiscal policy objective of enhancing the equity and efficiency of public services delivery. This view is supported by the fact that the local government fiscal reform took place in the nationwide response to the economic crisis in the early 1990s. On the other hand, this kind of co-ordinated response to an economic shock will not be easy for many countries to follow, as they do not have long-established institutions for intergovernmental co-ordination.

The central-local fiscal arrangement has important implications for the fiscal performance of a country. This is because subnational governments are responsible for the provision of essential redistributive public services such as health, education and social services. The challenges arising from the need to co-ordinate across levels of government for the provision of redistributive public services are not easily analysed with the traditional Tiebout–Musgrave–Oates framework. This is because the provision of essential public services is regulated by constitutions and laws, and is heavily influenced by national politics and the history of decentralisation. The international comparative studies and the benchmarking of best practices of other countries are helpful for appreciating the diversity of these challenges. However, it will be most beneficial when quantitative metrics such as the local tax share, the size of own revenue and the composition of intergovernmental grants are interpreted while understanding the institutions of intergovernmental relations in each country.

References

[43] Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance (2006), Reconciling the Irreconcilable: Addressing Canada’s Fiscal Imbalance, Council of the Federation, Ottawa.

[22] Aldasoro, I. and M. Seiferling (2014), “Vertical Fiscal Imbalances and the Accumulation of Government Debt”, IMF Working Paper, No. 14/209, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[37] Baicker, K., J. Clemens and M. Singhal (2012), “The Rise of the States: US Fiscal Decentralization in the Postwar Period”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 96/11-12, pp. 1079-1091.

[26] Bartolini, D., S. Stossberg and H. Blöchliger (2016), “Fiscal Decentralisation and Regional Disparities”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1330, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlpq7v3j237-en.

[10] Berkowitz, P. (2017), Conditionalities for More Effective Public Investment, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/Berkowitz_Conditionalities-for-More-Effective-Public.pdf.

[5] Blöchliger, H. and O. Petzold (2009), “Finding the Dividing Line Between Tax Sharing and Grants: A Statistical Investigation”, OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism, No. 10, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k97b10vvbnw-en.

[31] Boadway, R. (2004), “Should the Canadian Federation be Rebalanced?”, Economic Policy Research Institute Working Papers, No. 20041, University of Western Ontario, Ontario.

[13] Boadway, R. and L. Eyraud (2018), “Designing Sound Fiscal Relations Across Government Levels in Decentralized Countries”, IMF Working Paper, No. 18/271.

[19] Boadway, R. and J. Tremblay (2012), “Reassessment of the Tiebout model”, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 96/11, pp. 1063-1078.

[23] Boadway, R. and J. Tremblay (2006), “A Theory of Vertical Fiscal Imbalance”, FinanzArchiv, Vol. 62, pp. 1-27.

[18] Breton, A. (1996), Competitive Governments Cambridge: An Economic Theory of Politics and Public Finance, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

[49] Breton, A. and A. Fraschini (2007), “Competitive Governments, Globalization, and Equalization Grants”, Public Finance Review, Vol. 35/4, pp. 463–479.

[47] Council of Europe (1988), European Charter of Local Self-Government, Council of Europe, Strasbourg, https://www.coe.int/en/web/congress/european-charter-of-local-self-government.

[40] Department for Communities and Local Government (2008), Local Government Finance Key Facts: England, UK National Statistics Publication.

[12] Dolls, M. et al. (2019), Incentivising Structural Reforms in Europe? A Blueprint for the European Commission’s Reform Support Programme, European Network of Economic and Fiscal Policy Research, https://www.econpol.eu/sites/default/files/2019-02/EconPol_Policy_Brief_14.pdf.

[35] Edwards, C. (2019), Restoring Responsible Government by Cutting Federal Aid to the States, Cato Institute, Washington DC.

[21] Eyraud, L. and L. Lusinyan (2013), “Vertical Fiscal Imbalances and Fiscal Performance in Advanced Economies”, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 60, pp. 571-587.

[41] Jarrett, T. (2013), School funding: 2006–2010 policy changes under the Labour Government, House of Commons Library.

[25] Karpowicz, I. (2012), “Narrowing Vertical Fiscal Imbalances in Four European Countries”, IMF Working Paper, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[8] Kim, J., J. Lotz and N. Mau (eds.) (2010), Earmarked Grants and Accountability in Government, KIPF Korea Institute of Public Finance, Seoul and Danish Ministry of Interior and Health, Copenhagen.

[34] Kim, J., J. Lotz and N. Mau (eds.) (2010), General Grants Versus Earmarked Grants - Theory and Practice: The Copenhagen Workshop 2009, Korea Institute of Public Finance, Seoul and Danish Ministry of Interior and Health, Copenhagen.

[17] Kim, Lotz and Mau (eds.) (2014), Local Taxes And Local Expenditures: Strengthening the Wicksellian Connection, Korea Institute of Public Finance, Seoul and the Danish Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Interior, Copenhagen.

[48] Kim, Lotz and Mau (eds.) (2010), Conditional intergovernmental transfers in Italy after the constitutional reform of 2001, Korea Institute of Public Finance, Seoul and the Danish Ministry of Interior and Health, Copenhagen.

[30] Kirchgässner, G. (2013), “Fiscal Institutions at the Cantonal Level in Switzerland”, Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 149/2, pp. 139-166.

[32] Lazar, H. (ed.) (2005), The Vertical Fiscal Gap: Conceptions and Misconceptions, McGill-Queen’s Press, Montreal.

[14] Lazar, H. (ed.) (2000), Federal Financial Relations: A Comparative Perspective, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal and Kingston.

[2] McLure, C. (2001), “The tax assignment problem: Ruminations on how theory and practice depend on history”, National Tax Journal, Vol. 52, pp. 339-364.

[39] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2019), Local Authority Revenue Expenditure and Financing: 2019-20 Budget, England, UK Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government.

[45] Moisio, A. (ed.) (2010), Local government in Sweden, VATT (Government Institute for Economic Research), Helsinki.

[9] Oates, W. (2008), “On the Evolution of Fiscal Federalism: Theory and Institutions”, National Tax Journal, Vol. 61, pp. 313-334.

[24] Oates, W. (2006), “On the Theory and Practice of Fiscal Decentralization”, IFIR Working Papers No. 2006–05.

[16] Oates, W. (1972), Fiscal Federalism, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, New York.

[46] OECD (2018), OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/reg_cit_glance-2018-en.

[11] OECD (2018), Rethinking Regional Development Policy-making, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293014-en.

[38] OECD (2018), Revenue Statistics 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/rev_stats-2018-en.

[42] OECD (2017), “9. SNG budget balance and debt”, OECD.Stat, http://stats.oecd.org/ (accessed on 9 March 2020).

[36] Office of Management and Budget (n.d.), Table 12.2—Total Outlays for Grants to State and Local Governments, by Function and Fund Group: 1940–2024, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/.

[29] PBO (2018), Fiscal Sustainability Report 2018, Parliamentary Budget Office, Ottawa, Canada, https://www.pbo-dpb.gc.ca/en/blog/news/fsr_september_2018.

[6] Rodden, J. (2003), “Reviving Leviathan: Fiscal Federalism and the Growth of Government”, International Organization, Vol. 57, pp. 695-729.

[4] Rodden, J. (2002), “The Dilemma of Fiscal Federalism: Grants and Fiscal Performance around the World”, American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 46/3, pp. 670–687.

[27] Rodden, J., G. Eskeland and J. Litvack (eds.) (2003), Fiscal Decentralization and The Challenge of Hard Budget Constraints, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

[28] Rodden, J., G. Eskeland and J. Litvack (eds.) (2003), Soft Budget Constraints and German Federalism, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

[33] Sharma, C. (2012), “Beyond Gaps and Imbalances: Restructuring the Debate on Intergovernmental Fiscal Relations”, Public Administration, Vol. 90/1, pp. 99-128.

[44] SKL International (2014), Local Government in the Nordic and Baltic Countries.

[7] Stehn, S. and A. Fedelino (2012), Fiscal Incentive Effects of the German Equalization System, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

[50] St-Hilaire, F. (2005), Fiscal Gaps and Imbalances: The New Fundamentals of Canadian Federalism, The Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University.

[20] Ter-Minassian, T. and L. de Mello (2016), Intergovernmental Fiscal Cooperation, Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), Washington, DC.

[15] Tiebout, C. (1956), “A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures”, The Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 64/5.

[3] Watts, R. and P. Hobson (2000), Fiscal Federalism in Germany, Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario.

[1] Wildasin, D. (2004), “The Institutions of Federalism: Toward an Analytical Framework”, National Tax Journal, Vol. 57/2, pp. 247-72.

Notes

← 1. In this chapter, the terms “local” and “subnational” are used interchangeably.

← 2. See Kim, Lotz and Mau (2010[34]) for an extensive discussion on grant types.

← 3. “Local authorities shall be entitled, within national economic policy, to adequate financial resources of their own, of which they may dispose freely within the framework of their powers.” (Council of Europe, 1988[47])

← 4. “As far as possible, grants to local authorities shall not be earmarked for the financing of specific projects. The provision of grants shall not remove the basic freedom of local authorities to exercise policy discretion within their own jurisdiction.” Council of Europe (1988[47]), Article 9(7).

← 5. See Brosio and Piperno (2010[48]) for an explanation of Italy’s system of education grants.

← 6. “[T]he design and operation of systems of intergovernmental grants in a political setting is an issue of the first priority in fiscal federalism; we need to devote more attention to it.” (Oates, 2008, p. 326[9]).

← 7. Breton defines Wicksellian Connection as “a link between the quantity of a particular good or service supplied by centres of power and the tax price that citizens pay for that good or service.” (Breton and Fraschini, 2007, p. 466[49])

← 8. As will be discussed below, Boadway and Tremblay (2006[23]) clearly differentiate the concepts of VFI and transfer dependency.

← 9. For more information, see OECD Regions and Cities at a Glance (OECD, 2018[46]).

← 10. Boadway (2005[32]) notes, “the terms ‘vertical fiscal gap’ (VFG) and ‘vertical fiscal imbalance’ (VFI) have been used in various contexts, often interchangeably. They seem to mean different things to different persons. For our purposes, it is useful to refer to them as distinct concepts. The traditional meaning of a VFG comes from the fiscal federalism literature.”

← 11. See also St-Hilaire (2005[50]) and Advisory Panel on Fiscal Imbalance (2006[43]).

← 12. General grants (General Revenue Sharing) existed in the United States from 1972 through 1986. They were provided to states and localities to support “priority expenditures” such as public safety, environmental protection, public transportation, health, recreation, libraries, social services for the poor or aged and financial administration.

← 13. A summary of announced measures is at www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/ explainers/tax-and-devolution.

← 14. For more information, see Department of Finance Canada, Federal Support to Provinces and Territories (www.fin.gc.ca).

← 15. “The 2003 First Ministers’ Accord established an enhanced accountability framework under which all governments committed to provide comprehensive and regular reports to Canadians based on comparable indicators relating to health status, health outcomes, and quality of service”; for more information, see https://www.fin.gc.ca/fedprov/fihc-ifass-eng.asp.

← 16. For more information, see Statistics Sweden (https://www.scb.se/en/).

← 17. The operating income of the Swedish local governments consists of charges and fees for local services provided such as child, elderly and health care, rents, site leaseholds, etc. It also includes certain kinds of government grants (for example, grants for refugees).

← 18. Social protection accounted for 27.6%, health for 26.7%, and education for 21.0%. For more information, see World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Investment (www.sng-wofi.org).