3. Enhancing SME access to diversified financing instruments

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

-

Across all stages of their life cycle, SMEs require access to appropriate sources of financing for their creation, survival and growth.

-

Although SME access to bank finance largely recovered after the financial crisis, market failures and structural challenges remain, including information asymmetries, high transaction costs in servicing SMEs, and lack of financial skills and knowledge among small business owners.

-

There is a need to broaden the range of financing instruments available to SMEs and entrepreneurs, in order to address diverse financing needs in varying circumstances, increase SMEs’ resilience to changing conditions in credit markets and improve their contribution to economic growth.

-

Alternative financing instruments offer opportunities to meet SME financing needs. However, their potential remains underdeveloped in most countries due to demand- and supply-side barriers. Capital market instruments for SMEs often operate in thin, illiquid financial markets, with a low number of participants and limited exit options for investors.

-

The digital transformation holds potential to improve SME access to finance, offering unprecedented solutions to address barriers related to asymmetric information and collateral shortage. At the same time, it requires regulatory frameworks to support novel developments, while ensuring financial stability, consumer and investor protection.

-

Governments have been stepping up efforts to foster a diversified financial offer for SMEs, following the two-pronged policy approach advocated by the G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing, which call for strengthening SME access to credit, while also supporting the diversification of their financing sources.

Access to finance is key to the creation, growth and productivity of SMEs

Financing for SMEs in the appropriate forms is important at all stages of the business life cycle, in order to enable these firms to start up, develop and grow, and make contributions to employment, growth and social inclusion.

Access to finance improves post-entry performance of start-ups and industries which are more dependent on external finance grow relatively faster in countries with more developed financial markets, thanks to enhanced information sharing and risk management, and a better allocation of resources to profitable investment projects (Rajan and Zingales, 1998; Giovannini et al., 2013). On the other hand, financing constraints that prevent firms from investing in innovative projects, seizing growth opportunities, or undertaking restructuring in case of distress negatively affect productivity, employment, innovation and income gaps.

Longstanding challenges in accessing bank finance limit SME growth in many countries

Bank lending is the most common source of external finance for many SMEs and entrepreneurs, which are often heavily reliant on straight debt to fulfil their start-up, cash flow and investment needs (OECD, 2016a). SMEs, however, typically find themselves at a disadvantage with respect to large firms in accessing debt finance1. Asymmetric information and agency problems, including high transaction costs, and SMEs’ opacity limit access to credit by small businesses and start-ups, in particular, which are often under-collateralised, have limited credit history and, and may lack the expertise and skills needed to produce sophisticated financial statements (OECD, 2013). Access to debt finance is also more difficult for firms with a higher risk-return profile, such as innovative and growth-oriented enterprises, whose business model may rely on intangibles and whose profit patterns are often difficult to forecast (OECD, 2015).

In middle- and low-income countries, funding gaps are often even more pronounced and among the main barriers to small business formalisation. Moreover, while a large share of SMEs do not have access to formal credit, long-term credit to sustain investment and innovation is even scarcer, which severely limits growth opportunities (IFC, 2013).

The recovery in SME lending following the crisis has been uneven

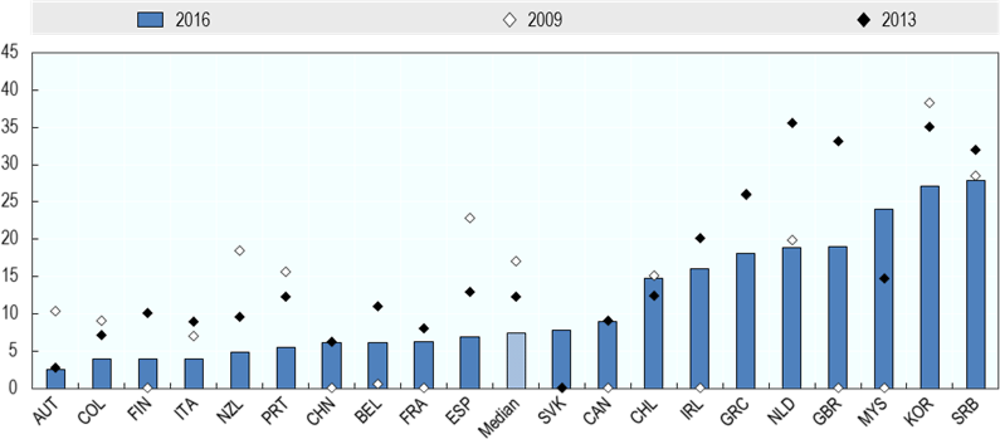

In many countries, the 2008-09 global economic and financial crisis exacerbated the financial constraints experienced by SMEs and resources dried up for the most dynamic enterprises. While in 2009, for instance, only 5.2% of loan applications were rejected among large firms, that share was double for small firms and even three times as large among micro businesses (European Commission, 2009) Although recent trends provide an indication of loosening credit conditions, large cross-country differences persist in the share of SMEs that experience full or partial rejection of their credit demand, which, in 2016, ranged from around 27% in Serbia and Korea, to 2.5% in Austria (Figure 3.1). In 2017, large firms continued to face a better financial situation and much lower bank loan rejection rates (1% vs. 6%) compared to SMEs (European Commission, 2017).

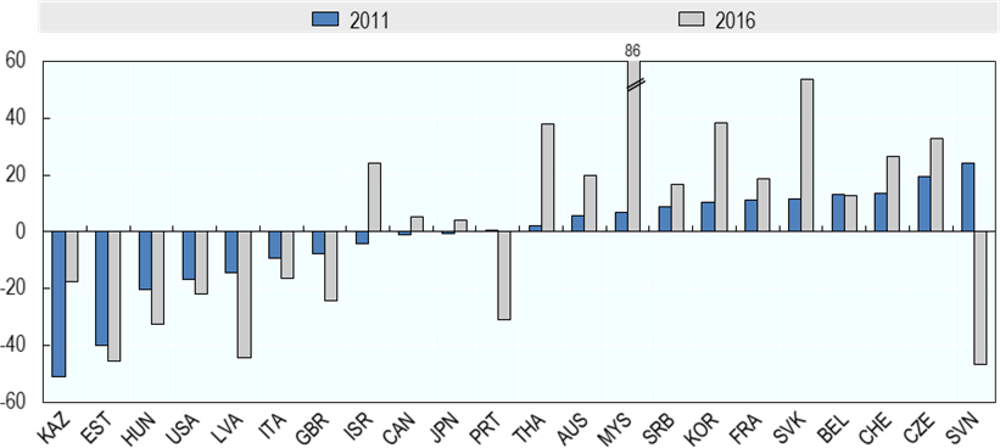

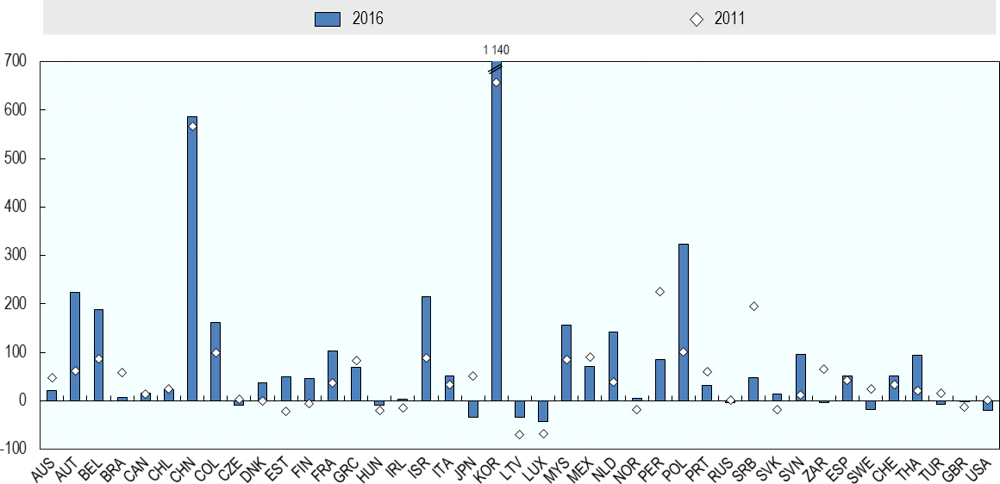

The financial crisis illustrated the vulnerability of many SMEs to changes in the credit cycle. During the uneven recovery, often marked by GDP contraction or slow growth in many countries, credit to SMEs followed a similar pattern or contracted even more sharply, with the exception of some emerging economies, where business loans expanded at a sustained rate (Figure 3.2).

In recent years, SMEs have found it easier to access credit and the economic environment in which they operate has generally improved, as evidenced by lower bankruptcy rates and shorter payment delays. However, this has not systematically led to more credit flowing to SMEs, in part due to weak credit demand and uneven investment opportunities (OECD, 2018a). Also, more rigorous prudential rules have led banks to modify their business model and adopt more stringent credit selection criteria.

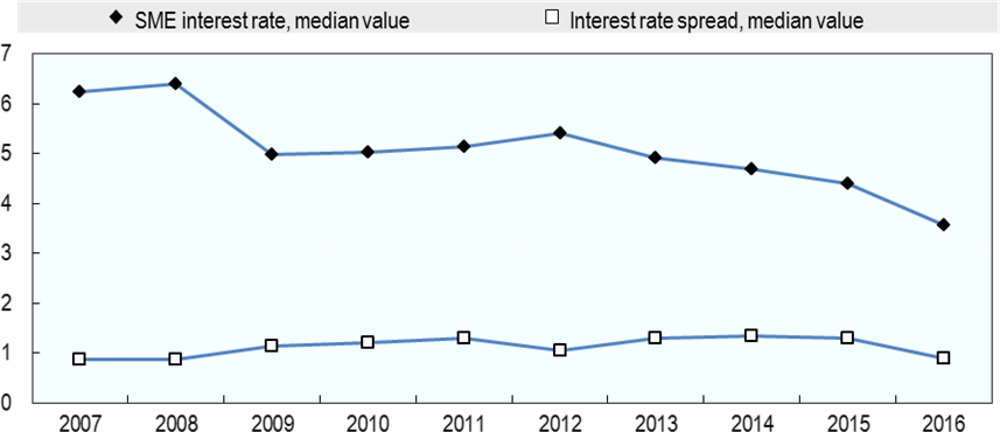

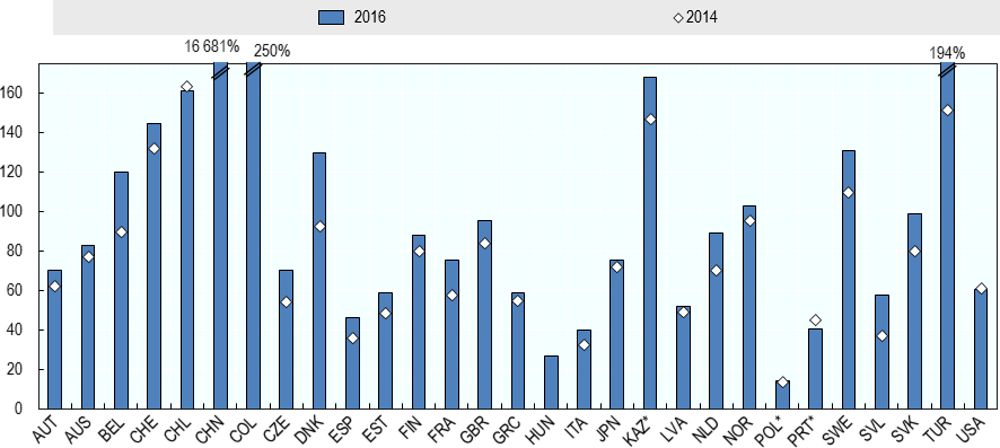

In addition, declining interest rates have benefited large enterprises more than small ones, pointing to a persistently higher credit risk for SMEs. In fact, across a large number of countries, the spread in the average interest rates charged to SMEs and to large firms has widened compared to the pre-crisis period (Figure 3.3). In 2008, the median interest rate charged to SMEs was 15.5% higher than the rate charged to large enterprises, whereas in 2016, that percentage had more than doubled, standing at 32.7%.

Certain categories of firms and entrepreneurs face higher barriers to accessing bank finance…

While credit has become more easily available for some SMEs, other segments of the SME population still face substantial difficulties in accessing debt finance. Transaction costs are particularly high in relative terms for micro-enterprises, start-ups, young SMEs, innovative firms and businesses located in remote and/or rural areas, potentially excluding them from any sources of formal external financing.

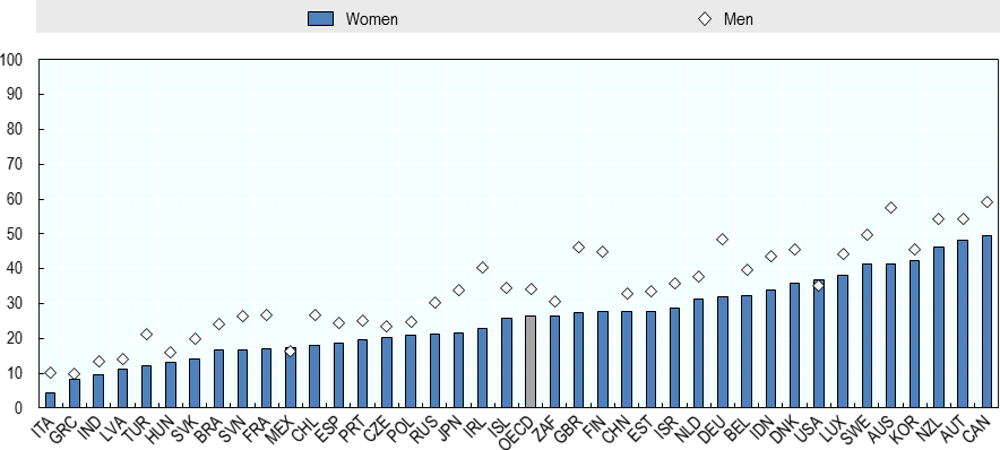

At the same time, these firms’ financing needs tend to be high compared to their turnover and assets, and they usually lack assets that are easy to collateralise. Moreover, evidence suggests that financial institutions have become more risk-averse compared to the pre-crisis period, and that the financing constraints of these firms may have become more structurally entrenched (OECD, 2017a). In addition, certain categories of entrepreneurs, such as women, migrants or youth, often face additional obstacles to accessing financing in the appropriate volumes or forms. For instance, in many countries, women are much less confident than men that they can obtain the financing they need to start or grow a business (Figure 3.4).

…as do many SMEs in emerging economies, in part because of high levels of informality

Small firms operating in developing countries are more likely to be credit-constrained and pay significantly higher interest rates than their counterparts in high-income countries. Firm-level data indicate that, while there are many barriers to SMEs’ growth in emerging and developing markets, insufficient access to financing is particularly constraining and represents the most robust barrier to firm expansion within the business environment (Dinh et al., 2010).

In part, that is because as many as 80% of firms in developing countries are estimated to be active in the informal sector, employing around 60% of the labour force. These enterprises are often fully or partially excluded from formal financial sector. Their reliance on internal revenues and informal, often very expensive, sources of external financing inhibits their growth potential and is associated with increased firm illegality.

Overall, SMEs remain too dependent on straight debt …

Many SMEs around the world remain heavily reliant on straight debt and are undercapitalised, which makes them more vulnerable to economic downturns and dependent on the health of the credit market. For instance, across eight continental European countries in 2014, bank loans constituted 23% of small and 20% of medium-sized firms’ balance sheets, compared with only 11% for large firms (Deutsche Bank, 2014).

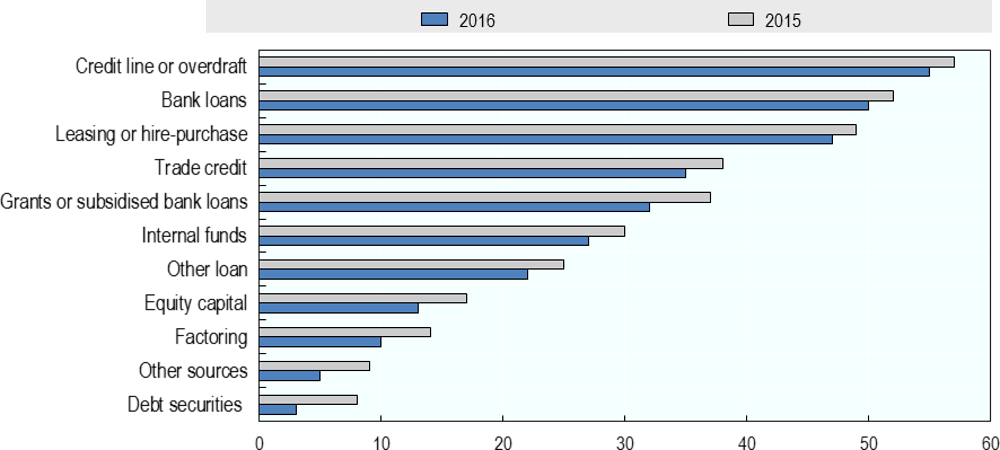

A more balanced capital structure may increase the likelihood of attracting bank credit at good conditions, and is associated with higher growth in employment and turnover (Brogi and Lagasio, 2016). However, only 13% of SMEs surveyed between October 2016 and March 2017 in the EU 28 considered equity financing as relevant for their business, i.e. had used it in the past or were considering doing so, a share significantly smaller than for most other sources of finance at their disposal (Figure 3.5).

… in a context of less credit as the “new normal”

Notwithstanding recent improvements, trends point to a business environment in which less credit is becoming the “new normal”, also as a result of financial reforms, which affect SMEs and entrepreneurs disproportionately, with banks continuously modifying their business models in response to more rigorous prudential rules (OECD, 2015).

Against this backdrop, the long-standing need to strengthen SME capital structures and decrease their dependence on borrowing has become more urgent. While bank financing will continue to be crucial for SMEs, a more diversified set of financing options can contribute to reducing systemic risk, increasing the resilience of the real economy to large shocks, and enable SMEs to continue to play their role in investment, growth, innovation and employment.

There are opportunities for SMEs to tap into a wide range of alternative financing instruments

In recent years, an increasing range of financing options has become available to SMEs, although some of these are still at an early stage of development or, in their current form, only accessible to a small share of SMEs.

While debt finance offers moderate returns for lenders and is therefore appropriate for low-to-moderate risk profiles, i.e. firms that are characterised by stable cash flow, modest growth, tested business models, and access to collateral or guarantees, alternative financing instruments alter this traditional risk sharing mechanism. These instruments consist of multiple and competing sources of finance for SMEs, including asset-based finance, alternative forms of debt, hybrid tools and equity instruments and not all are suitable and of interest for all enterprises, depending on their risk-return profile, stage in the business life cycle, size, scale, management structure and financial skills (Table 3.1).

Finance instruments that pose fewer risks to investors can flourish more readily and even in the absence of comprehensive, transparent, and standardised credit data, especially when backed by collateral or guarantees by the enterprise. Accessing asset-based finance, in particular, depends on the liquidation value of the underlying asset, rather than on the creditworthiness of the business. Survey data also show that these instruments are more widely known and used by entrepreneurs compared to riskier finance instruments (OECD, 2015).

Equity finance holds particular promise for firms with a high risk-return profile, such as new and innovative SMEs. Seed and early stage equity finance can boost firm creation and growth, while other equity instruments, such as specialised platforms for SME public listing, can provide financial resources to growth-oriented SMEs. Business angel investment may also play a significant role, although it is difficult to estimate their weight in SME financing due to data issues (OECD, 2015).

The private capital market, through a full range of debt and equity instruments, offers advantages for small firms with a higher risk profile seeking flexible form and conditions. Finance through capital markets often complements rather than replaces bank financing; banks typically provide short-term working capital, and may work with investors in order to steer companies toward a mix of financial products that suits their needs. This pattern of financing might become more prevalent in the future, with banks operating at the short-term low-risk part of the market, while investors focus on higher-risk high-reward and low liquidity operations (OECD, 2017b).

…but the development and use of alternative financing instruments by SMEs is highly uneven

Asset-based finance is widely used by SMEs across OECD countries, and increasingly in emerging economies, to meet their working capital needs, support domestic and international trade, and, in some cases, for investment purposes. In Europe especially, the prevalence of these instruments for SMEs is about on par with conventional bank lending. Moreover, asset-based finance has grown steadily over the last decade, in spite of repercussions of the global financial crisis on the supply side.

Factoring has become a more widely used and accepted alternative to liquidity-strapped SMEs in many countries, with volumes expanding significantly over the last decade, especially in emerging economies – although here often from a low base (Figure 3.7).

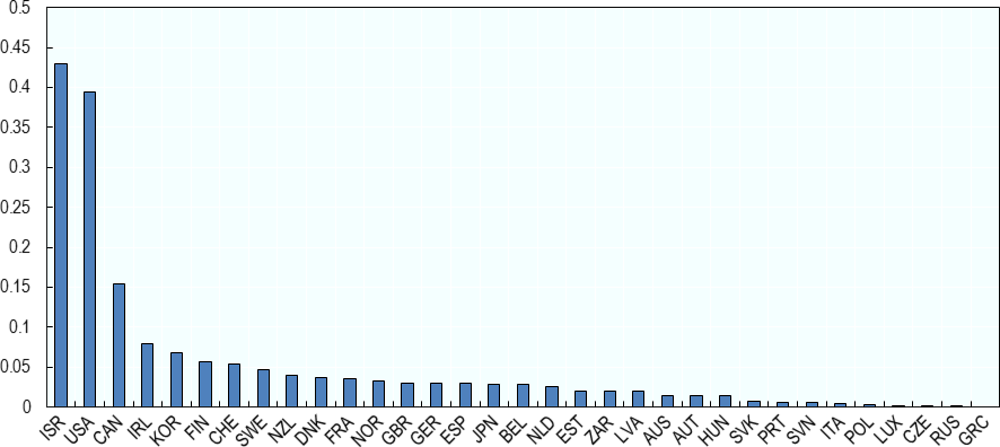

In contrast, venture and growth capital investments account for a very small share of SME financing, less than 0.03% of GDP in most OECD countries. However, the degree of development of capital market finance for SMEs differs widely among countries. Relative to the size of the economy, in Canada, Israel and the United States, venture capital investments are a multiple of activities in the Euro area. Even within continental Europe, large differences persist, with venture capital funding much more widely used in Finland, Sweden, and especially Switzerland, than in Central and Southern European countries (Figure 3.8).

Despite the relatively modest amounts of money involved, venture capital activities are believed to have a disproportionate economic impact. In the United States, for example, public companies with venture capital backing employ four million people, account for one-fifth of market capitalisation, and 44% of the research and development spending of public companies (Gornall and Strebulaev, 2015).

The capital market is particularly well suited to firms embarking on riskier endeavours, i.e. start-ups, fast-growing ventures, but also established firms undergoing a major transition, such as a change in ownership, accelerated growth or transformation into a firm with a stronger market position. Private equity, for instance, is a widely recognised vehicle for financing potential high growth SMEs, which depend on equity finance to realise their growth ambitions. Empirical evidence shows a positive and strong relationship between capital market financing and firm growth in a wide array of countries, especially for small firms (Didier et al., 2015). However, access to equity finance remains difficult in many countries, especially for fast-growing firms, with adverse implications for economic growth and inclusiveness.

…and remain underdeveloped due to a number of demand- and supply-side barriers markets

The availability and access to alternative sources of finance is held back by a combination of demand and supply-side barriers. On the demand side, many entrepreneurs and business owners lack financial knowledge, strategic vision, resources and sometimes even the willingness or awareness to successfully attract finance other than straight debt. The lack of appetite by SMEs for alternative financial instruments, equity in particular, can also be attributed to their tax treatment vis-à-vis straight debt. On the supply side, potential investors are held back by the overall opacity of SME finance markets, a lack of exit options and regulatory impediments. As a consequence, financial instruments for SMEs often operate in thin, illiquid markets, with a low number of participants, which, in turn drives down demand from SMEs and discourages potential suppliers of finance (OECD, 2017d; Nassr and Wehinger, 2016).

The digital transformation offers new opportunities to improve SME access to finance

The advent of Fintech (combining technology and innovative business models in financial services) has gained considerable momentum in recent years, with global investments rising at exponential rates. It holds the potential to revolutionise SME financing, as it can offer unprecedented solutions to deal effectively with the main barriers that SMEs face in financial markets: information asymmetries and collateral shortage (OECD, 2017d).

On the one hand, digital technologies, such as online and mobile banking and payment solutions, have had an important impact on traditional SME financing. They allow financiers to considerably lower transaction costs when reaching out to unserved and underserved segments of the SME population. They introduce accounting technology to help manage SME financial statements, as well as alternative credit scoring mechanisms using non-traditional sources of information, such as payment history, usage and payment of utilities, online activities and mobile history. These make lenders able to address information asymmetries in a cost-effective manner and enable higher approval rates with a relatively low default rate.

While traditional banks are investing in updating their business practices, many new-born Fintech companies are entering the market addressing an increasing demand for fully digital, remotely accessible and cheap financial services. Giant online merchants (e.g. Amazon, Alibaba) have also started to offer financing options for their clients, leveraging the wealth of information on their trading history and business behaviour. These developments are particularly relevant for emerging economies and small businesses that currently find it hard to access the formal financial sector, such as micro-enterprises, informal ventures and firms operating in rural and/or remote areas (OECD, 2017d). While new financing opportunities for entrepreneurs open up, the entry of large tech companies into the SME finance market might be disruptive for traditional players, and the overall implications of these changes need to be better understood.

Digitalisation has also allowed some innovative and inherently digital financial services to be offered to SMEs. Peer-to-peer lending and equity crowdfunding provide alternative sources of financing and have experienced rapid growth in many parts of the world, as they enable investment projects that are too small or too risky for traditional banks to address (World Economic Forum, 2015). They still represent a very minor share of financing for businesses; however, they are rapidly expanding from the starting non-profit and small scale entertainment niche, to for-profit activities and businesses (OECD, 2017a).

A major push in this direction is due to the development of Blockchain (i.e. Distributed Ledger) technology, which addresses information asymmetries and collateral shortage in an innovative way and is applicable to any digital asset transaction performed online. “Smart contracts" based on this technology can immediately execute transactions when certain agreed upon conditions are met, bypassing the need of any middle-man or the risk (and cost) of enforcement. Originally developed for the Bitcoin digital currency, the technology has turned out to be a multipurpose tool that could have a large impact on SMEs access to finance. Traditional financial players recognise the opportunity offered by this new technology and are moving accordingly. For instance, in Europe, the Digital Trade Chain Consortium was created in 2017, gathering major commercial banks, to build a new cloud-based platform based on blockchain technology, directed at SME clients. A similar project is being considered that would serve Japan and other countries in Asia (IBM, 2017).

The G20/OECD High Level Principles on SME Financing provide a comprehensive framework for policy makers

Recognising that financing needs and constraints vary widely across the SME population and along the life-cycle of firms, the G20/OECD High-level Principles on SME Financing advocate a holistic approach to address existing demand- and supply-side obstacles to SME financing, calling for strengthening SME access to credit, while also supporting the diversification of their financing sources (Box 3.1). The OECD is working to identify effective approaches for the implementation of the Principles, in order to support governments in designing appropriate policy measures that are suited to their national contexts and specific challenges of their SME population.

1. Identify SME financing needs and gaps and improve the evidence base.

2. Strengthen SME access to traditional bank financing.

3. Enable SMEs to access diverse non-traditional financing instruments and channels.

4. Promote financial inclusion for SMEs and ease access to formal financial services, including for informal firms.

5. Design regulation that supports a range of financing instruments for SMEs, while ensuring financial stability and investor protection.

6. Improve transparency in SME finance markets.

7. Enhance SME financial skills and strategic vision.

8. Adopt principles of risk sharing for publicly supported SME finance instruments.

9. Encourage timely payments in commercial transactions and public procurement.

10. Design public programmes for SME finance which ensure additionality, cost effectiveness and user-friendliness.

11. Monitor and evaluate public programmes to enhance SME finance.

Source: G20/OECD (2015)

Governments have been stepping up efforts to foster a diversified financial offer for SMEs

A range of government policies to foster SME access to finance have been introduced since the financial crisis, including new policy initiatives, scaling up existing measures and policy experimentation.

Credit guarantee schemes remain the most widely adopted policy instrument in OECD countries, and their design is continuously being revised to keep up with evolving needs. Export guarantees and measures to support trade credit, direct lending schemes, interest rate subsidies, as well as the provision of business advice and consultancy to SMEs looking for external finance constitute some other commonly used policy instruments.

At the same time, governments increasingly provide support for equity-type instruments, with initiatives that often target start-ups, innovative and fast-growing small businesses. This is the case, for instance, of regulatory reforms aimed at enabling crowdfunding activities. In some jurisdictions, public support for improving access to finance for (innovative) start-ups is being complemented by a comprehensive bundle of policy measures to address other challenges these firms face, such as a high regulatory burden, weak managerial skills, access to skilled labour, innovation and internationalisation.

For instance, in the framework of the Investment Plan for Europe (Juncker Plan), the European Fund for Strategic Investment (EFSI) was created in 2015, implemented and co-sponsored by the EIB Group, to address the paucity of alternative sources of finance for SMEs and mid-caps, by mobilising private capital, such as through guarantees and equity investments. Given its success, the SME window of the EFSI was scaled up in 2016. Furthermore, to improve the quality of investment projects, a European Investment Advisory Hub (EIAH) was launched, which acts as a single access point to tailored advisory and technical assistance services for European project promoters.

There is also an emerging trend towards tailoring SME financing policy approaches to local and regional circumstances. For example, in France, the Banque de France has created a network of regional correspondents, around 100 advisors, which provide advice on emerging financial problems to very small local firms. In the United Kingdom, in 2017, the British Business Bank launched its first regionally-focused fund, the /Northern Powerhouse Investment Fund (NPIF), in collaboration with ten Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs), to provide commercially-focused finance to help SMEs start up and grow (British Business Bank, 2016). In China, the national SME development fund, which was established in 2015, set up its first regional subsidiary fund in Shenzhen City in 2016. In 2017, a national programme of innovative demonstration cities for small micro-enterprises started, with the aim to fund directly innovative SMEs and entrepreneurship at the city level, or to improve the urban environment for SME innovation and entrepreneurship (OECD, forthcoming).

Efforts by governments to enable SMEs to fully reap the benefits of a more diversified financial offer should focus on several areas (OECD, 2015).

Improving SME skills and strategic vision for their financing needs

SME skills and strategic vision are key ingredients in any effort to broaden the range of financing instruments. Targeted financial education programmes are not only a matter of increasing knowledge about individual instruments. They can also help entrepreneurs to develop a long-term strategic approach to business financing, enhance understanding of the economic and financial landscape of relevance to their business, identify and approach providers of finance and investors, understand and manage financial risk for different instruments.

Complementing financial support for SMEs with non-financial elements, such as counselling and mentoring, can enhance SME financial skills and planning. In this regard, the providers of SME-targeted programmes, including governments, public financial institutions, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and relevant non-for profit institutions, can play a key role to foster SME financial capabilities. For example, in many of its programmes, the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) complements financial support with consulting services, and independent research indicates that this combined approach leads to a significant performance improvement by beneficiaries (OECD, 2017d).

While many countries have a national strategy in place to foster financial literacy, only few have a specific focus on SMEs, even though financial literacy needs of entrepreneurs go much beyond those of the general population (OECD/INFE, 2015). In Portugal, for example, financial education needs of SMEs are addressed in a comprehensive manner under the “National Plan for Financial Education.”

It is also necessary to improve the quality of start-ups’ business plans and SME investment projects, especially for the development of the riskier segment of the market. In many countries, a major impediment to the development of equity finance for young and small businesses is the lack of “investor-ready” companies. Furthermore, SMEs are generally ill-equipped to deal with investor due diligence requirements. In Italy, for instance, the ELITE programme, launched by the London Stock Exchange Group, helps growth-oriented SMEs to access the capital market by offering training, tutoring, and direct access to the financial community. A partnership with the Italian government started in 2017 to increase participation in the programme by innovative start-ups and SMEs from Southern Italian regions.

Designing effective regulation that balances financial stability and the opening of new financing channels for SMEs, including through digitalisation

The regulatory framework is a key enabler for the development of instruments that imply a greater risk for investors than traditional debt finance. In particular, efficient insolvency procedures and strong right enforcement mechanisms can increase the confidence of a broad range of investors in SME markets.

Designing and implementing effective regulation, which balances financial stability, investors’ protection and the opening of new financing channels for SMEs, represents a crucial challenge for policy makers and regulatory authorities. This is especially the case given the rapid evolution in the market, resulting from technological changes as well as the engineering of products that, in a low interest environment, respond to the appetite for high yields by financiers. In addition, new financing models, such as crowdfunding, are emerging that may engage relatively inexperienced investors.

While promising, the development of digital tools also poses challenges for policy makers, regulators and supervisory authorities. First, it is key to stay abreast of the rapidly evolving trends and developments in dialogue with traditional and new private sector partners. Second, the regulatory and supervisory framework needs to be accommodative of novel developments, while guaranteeing consumer protection, data protection and privacy restrictions and financial stability. In the European Union, for instance, the Directive PSD2 provides a legal framework promoting the use of innovative and disruptive solutions for banking and payment services (European Commission, 2015b).

Expanding access to financial services at a very rapid pace with lower controls might create a risk for systemic financial stability and of over-indebtedness for SMEs, which might be addressed by fostering financial literacy and awareness (Weidmann, 2017). Raising awareness about digital risks and enhancing digital skills is essential, also because continuous remote access implies that cyber risks extend to the personal devices (e.g. smartphones, personal computers) of borrowers, to which is to be added the possibility of larger attacks with data breach on the clouds. For instance, in response to this challenge, the French data protection agency, ANSSI and its German counterpart, BSI, jointly published a standard to be used to certify trustworthy providers of Cloud services with the Franco-German label: European Secure Cloud (ANSSI, 2017).

As financial and technological developments increasingly span the globe, close international cooperation can help to identify good practices and harmonise approaches.

Developing information infrastructures to reflect more accurately the level of risk associated with SME financing and encourage investors’ participation

Information infrastructures for credit risk assessment, such as credit bureaus, registries or data warehouses with loan-level granularity, can reduce the perceived riskiness investors fear when approaching SME finance and help them identify investment opportunities (Box 3.2). More reliable information about risk may also help reduce higher financing costs typically associated with SMEs.

One of the main difficulties faced by SMEs in accessing financial markets is related to information deficiencies that prevent investors from reliably assessing the risks and potential benefits from investing in them. The development of a credit risk assessment infrastructure plays a crucial role in overcoming existing information asymmetries and improving transparency in SME finance markets:

-

Japan established its Credit Risk Database (CRD) in 2001, led by the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency (SMEA). The CRD provides credit risk scoring, data sampling, statistical information and related services. It therefore not only facilitates SMEs’ direct access to the banking sector, but also smooths access to the debt market by enabling the securitisation of claims.

-

In France, the Euro-Secured Notes Initiative (ESNI) aims to overcome information asymmetries that limit the development of a well-functioning securitisation market for SME assets by making use of the Banque de France’s credit assessment of non-financial companies, as well as the internal ratings from banks. The ESNI was set up in March 2014 as a Special Purpose Vehicle by private banking groups and with support from the Banque de France. The securities, regulatory and banking supervisory authority ensures that the scheme complies with existing regulation.

Source: OECD (2017d).

In some countries, policies seek to address the information gap between SMEs and potential investors by facilitating their direct interaction, with different degrees of public engagement, from awareness campaigns to brokerage and match-making. In the business angel market, for instance, public action has largely aimed at improving information flows and networking opportunities between financiers and entrepreneurs. In some cases, however, the facilitation efforts have not produced the desired results, due to the lack of maturity of local markets, i.e. little scale or lack of investor-ready companies. This highlights the need for a policy mix that takes into account existing limitations on both the supply and the demand sides (OECD, 2016b).

Many obstacles also persist to unlock SME financing through intangible assets2, which make up an increasing part of SMEs’ value, especially of innovative ones. Recent initiatives have mainly focused on helping the market determine which company-owned intangible assets have realisable value, with most of the activity concentrated in Asia, such as the provision of subsidised IP evaluation reports in Japan. In China, the State Intellectual Property Office acts as a central registry of pledges and evaluation regimes, complemented by a set-up of measures to stimulate IP financing techniques, such as state-backed compensation schemes to cover bad debts, a guarantee coverage of up to 100% under certain conditions, lender incentives (dependent on the relative number of IP-backed loans), interest rate subsidies for IP-backed loans, and dedicated funds. The Korean Development Bank has initiated loans for purchasing, commercialising and collateralising IP, and its credit guarantee institution offers underwriting for an IP valuation for lending or securitisation (OECD, 2017e).

Leveraging private resources and develop appropriate risk-sharing mechanisms with the private sector

Policy can play a role in leveraging private resources and competencies and develop appropriate risk-sharing and mitigating mechanisms, such as through co-investment or guarantee schemes and private-public equity funds. Governments can contribute to raise awareness and improve knowledge by different financial providers about investment opportunities in SMEs, by raising the profile of the public debate about SME finance market development and investors’ advantages from diversification in the SME asset class; by improving visibility of successful transactions and platforms for alternative instruments; and by facilitating information sharing between investors and SMEs.

Direct investments by governments through funds, matching or co-investment funds and funds-of-funds have been identified as an effective means of addressing supply-side gaps in the availability of start-up and early stage capital since they can increase the scale of SME markets, enhance networks and catalyse private investments that would not have materialised in the absence of public support. Israel’s Yozma programme, the Danish Growth Capital Fund or the Turkish Growth and Innovation Fund – all based on co-investments between the private and public sector - are prominent examples in this respect. Governmental VC schemes also seem more successful when operating alongside private investors, rather than through direct public investments. Indeed, in recent years in many OECD countries the focus of support instruments has shifted from government equity funds investing directly to more indirect models such as co-investments funds and fund-of-funds (European Investment Fund, 2015).

Improving the evidence base

In most OECD countries, there is an established framework to collect quantitative data on SME access to finance, including by conducting demand and supply-side surveys. By providing a framework for data collection and information on policy initiatives, the annual OECD Scoreboard on Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs serves as the international reference for monitoring developments and trends in SME and entrepreneurship finance and financing conditions, thus improving cross-country analysis and comparability and supporting the formulation and evaluation of policies in this domain.

However, national data collection efforts usually focus on traditional bank finance, while the evidence about SME access to alternative financing tools remains patchy. Moreover, while quantitative data on SME finance are often broken down by the size of the enterprise, more granular data by other relevant parameters such as the business age, location, sector, export status and innovativeness are available only in a minority of countries. Similarly, only few countries gather detailed data broken down by key characteristics of principal business owner, such as age, educational attainment, business experience or gender (OECD, 2018b).

The lack of hard data, especially on non-debt financing instruments, represents an important limitation for the design, implementation and evaluation of policies in this area. This limitation is particularly critical when seeking to take account of SME heterogeneity and the varying nature of finance gaps in the process of policy design. Better micro data and micro level analysis, along with a stronger culture of evaluation are therefore essential to improve understanding about the different needs of SMEs and effectiveness of policy interventions, as well as the potential and challenges of new business models emerging in the financial sector.

References

ANSSI (2017), European Secure Cloud – A new label for cloud service providers, Official press release, Agence nationale de la sécurité des systèmes d'information, France https://www.ssi.gouv.fr/en/actualite/european-secure-cloud-a-new-label-for-cloud-service-providers/

British Business Bank (2016), Small Business Finance Market 2015/16, British Business Bank Plc, February 2016, http://british-business-bank.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/British-Business-Bank-Small-Business-Finance-Markets-Report-2015-16.pdf.

Brogi, M. and V. Lagasio (2016), “SME Sources of Funding: More Capital or More Debt to Sustain Growth? An Empirical Analysis, Access to Bank Credit and SME Financing”, in Rossi S. (eds) Access to Bank Credit and SME Financing. Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Banking and Financial Institutions. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41363-1_7.

Deutsche Bank (2014), SME financing in the euro area: New solutions to an old problem, EU Monitor Global Financial Markets, https://www.dbresearch.com/PROD/DBR_INTERNET_EN-PROD/PROD0000000000344173/SME+financing+in+the+euro+area%3A+New+solutions+to+an+old+problem.PDF.

Didier, T., Levine, R. and Schmukler. S. (2015), "Capital market financing, firm growth, and firm size distribution", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7353, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/358221468187797236/pdf/WPS7353.pdf.

Dinh, H. T., Mavridis, D., and Nguyen, H. (2010), "The binding constraint on firms' growth in developing countries", World Bank Policy Research Paper 5485, https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/1813-9450-5485.

European Commission (2017), Survey on the Access to Finance of Enterprises in the euro area, October 2016 to March 2017, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/ecb.accesstofinancesmallmediumsizedenterprises201705.en.pdf?17da4ff2a730b7ababea4037e4ce8cae.

European Commission (2015a), Survey on the access to finance of enterprises (SAFE), Analytical Report 2015, http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/7504/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

European Commission (2015b), European Parliament adopts European Commission proposal to create safer and more innovative European payments, Official press release, European Commission, Brussels http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5792_en.htm.

European Commission (2009), Survey on the access to finance of enterprises (SAFE) - summary (2009), http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/flash/fl_271_en.pdf.

European Investment Bank (2014), Unlocking lending in Europe, http://www.eib.org/attachments/efs/economic_report_unlocking_lending_in_europe_en.pdf.

European Investment Fund (2015), European Small Business Finance Outlook, December 2015, Working Paper 2015/32, www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eif_wp_32.pdf.

G20/OECD (2015), High-Level Principles on SME Financing, http://www.oecd.org/finance/G20-OECD-High-Level-%20Principles-on-SME-Financing.pdf.

Factors Chain International (2017), Factoring Turnover by Country in the last 7 years, https://fci.nl/about-factoring/2016_public_market_survey_outcome.xls.

Giovannini A., Iacopetta M. and R. Minetti (2013), "Financial Markets, Banks, and Growth: disentangling the links", Revue de l’OFCE 2013/5 (N° 131), p. 105-147, https://doi.org/10.3917/reof.131.0105.

Gornall A. and Strebulaev I. A. (2015), "The Economic Impact of Venture Capital: Evidence from Public Companies", Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper No. 15-55, available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2681841.

IBM (2017), Seven Major European Banks Select IBM to Bring Blockchain-based Trade Finance to Small and Medium Enterprises, Official press release: http://www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/52706.wss.

IFC (2013), Closing the Credit Gap for Formal and Informal Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises, International Finance Corporation, World Bank Group, Washington D.C.

LeasEurope (2017), Annual Survey 2016, http://www.leaseurope.org/uploads/documents/stats/European%20Leasing%20Market%202016.pdf.

Nassr, I.K. and Wehinger, G. (2016), “Opportunities and limitations of public equity markets for SMEs”, OECD Journal: Financial Market Trends, Vol. 2015/1, https://doi.org/10.1787/fmt-2015-5jrs051fvnjk.

OECD (2018a), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2018: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2018-en.

OECD (2018b), “G20/OECD Effective Approaches for Implementing the G20/OECD High-Level Principles on SME Financing”, OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/g20/Effective-Approaches-for-Implementing-HL-Principles-on-SME-Financing-OECD.pdf

OECD (2017a), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2017: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2017-en.

OECD (2017b), Alternative Financing Instruments for SMEs and Entrepreneurs: The Case of Capital Market Finance, OECD Publication, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dbdda9b6-en

OECD (2017c), Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2017-en.

OECD (2017d), "Fostering Markets for SME Finance: Matching Business and Investor Needs", OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2017-6-en

OECD (2017e), “Fostering the use of Intangibles to strengthen SME access to finance”, OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/729bf864-en

OECD (2016a), "G20/OECD Support Note on diversification of financial instruments for SMEs", considered by G20 finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors in Chengdu and transmitted to G20 leaders, https://www.oecd.org/g20/summits/hangzhou/G20-OECD-Support-Note-on-Diversified-Financial-Instruments-for-SMEs.pdf

OECD (2016b), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2016: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fin_sme_ent-2016-en.

OECD (2015), New Approaches to SME and Entrepreneurship Financing: Broadening the Range of Instruments, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264240957-en.

OECD (2013), "SME and Entrepreneurship Financing: The Role of Credit Guarantee Schemes and Mutual Guarantee Societies in supporting finance for small and medium-sized enterprises", OECD Working Party on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, https://doi.org/10.1787/35b8fece-en

OECD/INFE (2015), OECD/INFE Progress Report on Financial Education for Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs) and Potential Entrepreneurs, September 2015, https://www.gpfi.org/sites/default/files/documents/08-%20OECD-INFE%20Progress%20Report%20on%20Financial%20Education%20for%20MSMEs.pdf.

Rajan R. G. and L. Zingales (1998), “Financial Dependence and Growth”, American Economic Review, 88(3): 559-86.

Weidmann J. (2017), Digital finance – Reaping the benefits without neglecting the risks, Welcoming remarks by Dr Jens Weidmann, President of the Deutsche Bundesbank and Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Bank for International Settlements, at the G20 conference "Digitising finance, financial inclusion and financial literacy", 25 January 2017, Wiesbaden, https://www.bis.org/review/r170125d.htm.

World Economic Forum (2015), The Future of FinTech: A Paradigm Shift in Small Business Finance, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/IP/2015/FS/GAC15_The_Future_of_FinTech_Paradigm_Shift_Small_Business_Finance_report_2015.pdf.

Notes

← 1. Traditional debt includes instruments such as bank loans, overdrafts, credit lines and the use of credit cards.

← 2. Intangible assets are defined as identifiable non-monetary assets without physical substance, such as patents, copyrights, brand equity, software of computerised databases.