Chapter 4. Financing Community Education and Training

The improvement and further development of South Africa’s community education and training system will require considerable investment. This investment is needed to further improve current provision, but also to pilot and roll out new training programmes and services. This chapter looks at possible sources of funding for the community education and training system, and highlights the priority funding areas for which these resources should be mobilised.

4.1. Background

In most countries, the resources allocated to training opportunities for adults are much smaller than those for compulsory and post-secondary education. According to FiBS and DIE (2013[1]), total adult learning spending (by all actors) across a set of OECD countries in 2009 accounted for 0.9% of GDP on average, compared to 2.7% of GDP for primary education, 1.3% for upper secondary education, and 1.6% for tertiary education. The main contributors to the financing of adult education and training are generally employers, individuals and governments. The share of these actors in total spending varies between countries, but on average across OECD countries with available information, employers bear the largest share of adult learning costs (45% of total spending on adult learning on average), followed by individuals (23.3%) and the state (21%) (FiBS and DIE, 2013[1]). In general, comprehensive and comparable data on expenditure on adult learning is scant, mainly because of the scattered nature of the adult learning policy domain that has many different stakeholders involved in the financing and delivery of training programmes.

As argued by OECD (2019[2]), it would be advisable to have a health mix of financial resources for adult education and training, as benefits of a better skilled population accrue to employers, individuals and the society more broadly. Governments contribute to this healthy mix by directly providing fully subsidized training opportunities, but also indirectly through the availability of financial incentives, such as subsidies and tax deductions.

In general, financing of education and training can be analysed from three perspectives (UNESCO, 2017[3]):

-

Adequacy: Ensuring that sufficient resources are mobilised to provide education and training of high quality for all participants. Without reaching a minimum threshold of inputs and resources, the education and training system cannot produce the expected results. To ensure adequacy of the budget, many countries do not rely on public funding only, but also attract private resources.

-

Efficiency: Mobilising and managing financial resources to provide good quality and effective education services at the least cost. In decentralised systems, efficient allocation of funds to schools ensures that resources available for schools correspond to their specific needs and performance (e.g. in terms of student numbers, share of disadvantaged students, learning outcomes). An efficient use of funding also means avoiding duplication of investment.

-

Equity: Resources need to be allocated in an equitable way that is both fair and conductive to inclusiveness. In order to address equity concerns it is necessary to adjust spending to reach disadvantaged groups. Resource allocation to schools needs to take into account the particular challenges involved in reaching disadvantaged groups and ensuring high completion rate for these groups.

All three elements are crucial and well-functioning education and training systems take a holistic approach to financing that ensures adequacy, efficiency and equity at the same time. As pointed out by OECD (2017[4]), the sources of education funding are becoming increasingly diverse. While the central government remains the main funder of education institutions in most countries, other actors, such as sub-central governments and private actors, are increasingly providing complementary funds. In such a multi-level and multi-actor governance system of funding, adequate institutional and regulatory frameworks to optimise the role of each actor in ensuring an effective and equitable allocation of funds becomes crucial.

4.2. Potential funding sources

Public funding for CET is limited today (see Chapter 1), and it will be crucial to attract additional funding to achieve the desired growth to reach the target of 1 million adult participants by 2030. A projection exercise calculated that if funding for CET were to follow its historical trend, there would be a ZAR 16.88 billion shortfall to reach the White Paper’s goals by 2030 (DNA Economics, 2016[5]).1 While this exercise is based on a set of strong assumptions, it does provide a useful ballpark estimate of required additional funding. In ensuring that sufficient funding is available for the expansion and improvement of CET in South Africa, a mix of financial resources should be attracted, avoiding too much of the burden falling on one actor. Resources could be mobilised from different government departments, employers, individuals and external donors. Several policy documents related to CET have explicitly mentioned that the financial burden on individuals should be minimised, especially since the target audience of CET consists largely of disadvantaged adults with limited financial resources.

Different levels of government contribute to the financing of training opportunities

As discussed in Chapter 1, national government expenditure on CET is relatively low, and is not expected to increase substantially in the short or medium term. Especially in light of the relatively modest growth forecasts for the South African economy2, the budgetary situation will probably remain tight in the coming years. For the financial year 2017/18, the budget for CET equals ZAR 2 198 million. This central government budget is almost entirely reserved for expenditure on compensation of employees (92.3%), leaving only a very small amount for the investment in further development of the CET system. While it is highly unlikely that the CET system will be granted a large amount of extra funding from the National Treasury in the coming years, the Department for Higher Education and Training could request additional funding for specific areas or pilot projects. For this, it will be important for the Department to have clear and well-developed plans.

Provincial governments also invest in skills development, albeit generally outside the CET system. Receipts in the provincial budget mainly consist of transfers from the national government. To get a sense of the size of the provincial budgets, the estimated 2017/18 total budget for the Gauteng province, which accounts for 25.3% of the South African population, equals ZAR 108.8 billion. The largest shares of the provincial budgets are spent on (basic) education and health (37.6% and 37.0% respectively in the Gauteng Province). Skills development outside of basic education can be part of different areas of provincial budgets. In the Gauteng province, for example, the budget sets targets for youth skills development (37 651 participants), parenting skills programmes (15 531 families) and skills development and training programmes for integrated economic development (2 685 participants). Box 4.1 provides an example of a large-scale skills programme led by the Gauteng province.

Municipal governments also have their own budget to invest in a range of areas. Part of their budget comes from national and provincial government transfers, but the majority are own revenues, like property rates and the sale of electricity and water. The largest expenditure areas are employee-related costs and the purchase of electricity (Statistics South Africa, 2017[6]). One of the objectives of municipalities is to promote social and economic development, which has led some municipalities to offer skills programmes. In Stellenbosch, for example, the municipality-sponsored Youth Skills Development Programme offers accredited skills training programmes to a number of unemployed youth. Similarly, the city of Cape Town provides programmes and workshops to support young job seekers, including employment and work readiness skills, organisational capacity building, life skills and career guidance.

In 2014, the Gauteng provincial government launched the Tshepo 500 000 programme, aimed at training, skilling and mentoring 500 000 youth in the period 2014-19. The target was increased to 1 million in 2017, renaming the programme Tshepo 1 Million. In the first three years of the programme, 450 000 young people participated. The four key focus areas of the programme are:

-

Demand-led learning: skills development related to verifiable market demand

-

Transitional placements: Paid work done on a temporary basis aimed at developing work experience and/or sector specific skills

-

Decent jobs: Paid work on contract at or above the sectoral minimum wage for full-time work, preferably permanent

-

New economy/SMMEs: Facilitation of young entrepreneurs establishing and operating new enterprises/franchises

Part of the project is the mass digital learning system that is hosted in government sites, such as libraries, school and community centres. The system provides video learning for various types of opportunities, including the Matric re-write. The system also includes the Microsoft Thinti’Imillion initiative, a desktop and phone application designed to teach Microsoft Word, Excel and Powerpoint to people who have never used a computer.

An important part of the programme is the profiling of candidates, for which a partnership with Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator is set up. This partnership manages the pathway of each young jobseeker who enters the programme via a series of interventions, matching each entrant to the most viable pathway based on their skills profile, geography, learning potential, aptitudes, level of self-management and other relevant personal factors. When selected for a specific pathway, participants will often receive bridging and competency training to move them from their current situation to where the opportunity requires them to be in terms of capabilities, work-readiness, behaviours and work-habits.

To facilitate the creation of internship opportunities for youth in the province, the Tshepo 1 Million project benefits from a strong and growing network of business relationships. The programme also supports the growth of SMMEs, through cooperation with the Youth Employment Services (YES), the CEO initiative and Business Leadership South Africa, so that internships can also be created in smaller and informal businesses.

Source: Gauteng Province Office of the Premier (2017[7]; 2018[8]; 2018[9])

Recommended action steps

Table 4.1 provides some possible action steps that could be taken to obtain or channel funding from the central, provincial and/or municipal government budgets for CET. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

The National Skills Fund should become a key contributor to CET development

The National Skills Fund (NSF) was established in 1999 by the National Skills Development Act, with the goal to provide funding for national skills priorities. The NSF is funded through the skills development levy, which allocates 20% of the funds collected from employers to the NSF (see Chapter 1). Since 2014/15 the NSF also receives the uncommitted surpluses of SETAs. In the financial year 2016/17, the NSF received just over ZAR 3 billion in levy payments. The NSF spends its funds in four broad areas: i) education and training, ii) post-school education and training system development and capacity building, iii) “no fee increase”3, and iv) skills development research, innovation and communication. Spending by the NSF increased substantially in the last years, reaching ZAR 5 billion in 2016/17 (Figure 4.1). Spending on education and training accounted for 47% of total expenditure, benefitting 48 169 learners. The largest part of the budget for education and training was spent on higher education (57%), although the largest number of learners (52%) were in workplace-based training. The number of learners benefiting from NSF funding has decreased substantially over the years, and now reaches less than half of the number of learners in 2011/12. The strong decline can partially be attributed to the NSFs contribution to the “no fee increase” in recent years, but also to a stronger focus on infrastructure development.

According to the third National Skills Development Strategy, the NSF should enable the state to drive key skills strategies as well as to meet the training needs of the unemployed, non-levy-paying cooperatives, NGOs and community structures and vulnerable groups. Among the key priorities identified in the Strategy are “Addressing the low level of youth and adult language and numeracy skills to enable additional training”, as well as “Encouraging and supporting cooperatives, small enterprises, worker-initiated, NGO and community training initiatives”. These objectives are in line with the envisaged goal of the CET system. Given that the NSF’s mandate is to fund skills priorities and training of the unemployed and vulnerable groups, it should play a key role in the financing of the CET system. Notwithstanding, in the last years, the largest part of NSF funding has been targeted toward university education, as higher education received the majority of education and training funding, as well as large sums for system development and capacity building. In addition, 35% of the total NSF skills development expenditure in 2016/17 was for the “no fee increase” in universities and TVET colleges.

As Figure 4.1 shows, the NSF has built up large reserves over the years, because of underspending in initial years, as well as the transfer of SETA surpluses in recent years. The 2016/17 NSF annual report notes that the NSF has committed and earmarked its entire reserve and accumulated surplus towards skills development programmes and projects. The majority of the already committed funding is for post-school education and training system development and capacity building (63%).

Recommended action steps

Table 4.2 provides some possible action steps that could be taken to obtain additional funding from the National Skills Fund for CET. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

Sector Education and Training Authorities need to spend their funds more efficiently

Sector Education and Training Authorities (SETAs) are key players in the South African skills development system. By redistributing the skills development levy (see Chapter 1), they fund training opportunities for a large group of employed and unemployed individuals. In the financial year 2016/17, SETAs received ZAR 12.2 billion levy income. Using SETA funding, 130 353 workers and 114 230 unemployed entered into skills programmes and learnerships or received bursaries. In addition, the funds were used to support non-governmental and community organisations, and to provide career guidance. SETA levy revenues are expected to increase to ZAR 15.855 billion by 2020/21. SETAs on the whole experienced surpluses during most years up to 2015/16. This can be ascribed to: i) mandatory grants not having been claimed by employers; ii) intended grant beneficiaries not having met the criteria that would have made them eligible for funding; iii) the fact that resources are committed for a longer time horizon; and iv) a weak implementation culture in SETAs (Department of Higher Education and Training, 2016[12]). As mentioned above, in recent years surpluses have been transferred to the National Skills Fund.4

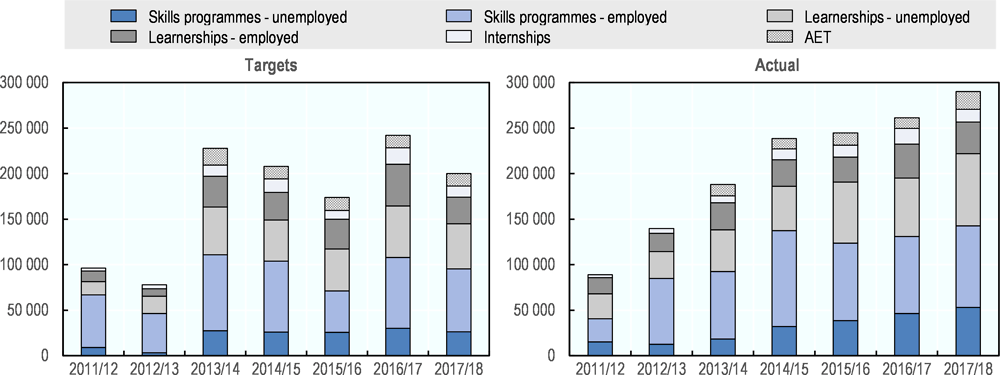

Every year, the Department for Higher Education and Training (DHET) concludes service level agreements with the SETAs. These agreements set targets in ten areas: i) administration; ii) research and skills planning; iii) occupationally directed programmes; iv) TVET college programmes; v) low level youth and adult language and numeracy skills; vi) workplace-based skills development; vii) support to co-ops, small enterprises, NGOs and worker initiated/community training initiatives; viii) administration and public sector capacity; ix) career and vocational guidance; and x) medium-term strategic priorities. As Figure 4.2 shows, the targets for the different types of training programmes across all SETAs have remained relatively stable in recent years. Targets for certain programmes even declined in the last year. Actual participation increased gradually in all programmes. To ensure that SETAs remain committed to invest in skills development, ambitious targets need to be set, especially in light of growing funds from the skills development levy and underspending of SETAs. At the same time, the performance of SETAs should not only be measured in terms of training quantity, but also training quality.

Figure 4.3 shows that targets for learnerships, skills programme, internships and second chance primary and secondary education (AET) registrations differ strongly between SETAs. In total, SETAs exceeded their target for learnerships for workers in 2017/18 by 29% and for the unemployed by 103%. For the skills programmes, the target was exceeded for workers by 19% and for the unemployed by 60%. Targets were also exceeded for internships (16%) and AET participation (43%). While targets were surpassed on average, there were some SETAs that did not manage to reach their targets.

Recommended Action steps

Table 4.3 provides some possible action steps that could be taken to channel funding from the skills development levy to CET. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

Other potential funding sources need to be considered

The Unemployment Insurance Fund could expand its funding of training opportunities

Employers and workers contribute to the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF), each at a rate of 1% of the workers’ monthly pay. The Fund is used to provide short-term relief to workers when they become unemployed or unable to work. Unemployed individuals can claim unemployment benefits at labour centres only if they are registered as job seekers. They need to return to the labour centre every four weeks to confirm unemployment status. Individuals who have contributed to the fund for a continuous period of at least four years can have access to benefits for the maximum duration of 365 days, others receive one day of benefits for each five days worked and contributed to the UIF. The Fund pays a percentage of the wage earned while contributing, with a maximum of 58%. In the financial year 2016/17, 763 000 valid claims were received. With a total number of unemployed individuals in the same period equal to around 6 011 000, this translates into a coverage rate of roughly 12.7%. According to Bhorat, Goga and Tseng (2016[13]) the relatively stringent rules of the South African unemployment insurance system exclude many vulnerable groups, such as informal workers, individuals without work experience and individuals in unstable jobs. The relatively low replacement rates, at least compared to OECD countries on average, potentially also make it not seem worthwhile for job seekers to claim their benefits.

In the financial year 2016/17, the revenues of the fund equalled ZAR 18.25 billion, and benefit payment amounted to ZAR 8.47 billion. As revenues have been exceeding benefit payments in most years, the UIF has been able to accumulate a substantial reserve (ZAR 139.5 billion in 2016/17).5 In view of making better use of the available funds, the latest amendment of the Unemployment Insurance Act (2015) specified that the UIF funds can also be used for “financing of the retention of contributors in employment and the re-entry of contributors into the labour market and any other scheme aimed at vulnerable workers”. This amendment makes it possible for the UIF to fund training programmes for contributing workers and job seekers. For the financial year 2017/18, the UIF set aside funding to train at least 6 000 individuals. To deliver the training, the Department of Labour collaborates with accredited public training providers (public higher education institutions, public TVET colleges, public entities and state owned enterprises) and SETAs. The Department launches an expression of interest for these institutions to submit proposals for apprenticeships, learnerships, unit standards based skills programmes, and new venture creating programmes. Training programmes can be either fully funded by the UIF or co-funded.

In most OECD countries, the responsibility of helping job seekers into employment lies with the Public Employment Service (PES). An international survey showed that in 70 out of 73 participating countries, PES provide a range of active labour market programmes to improve the employment outcomes of job-seekers (IDB, WAPES, OECD, 2015[14]). These active support measures often include skills development programmes. While the PES in most cases are not the direct providers of the training programmes, they do select available training programmes and provide funding. As the ultimate goal of PES is to help job seekers into sustained employment, they generally provide training programmes that are aligned with the needs of employers in the local labour market. In a range of countries, contributions to unemployment insurance are used to finance these and other activities of the PES. To make the most effective use of often-limited financial resources, some countries have put in place comprehensive profiling tools to better allocate resources to different groups of job seekers (see Box 4.2).

The Expanded Public Works and Community Works Programmes need a training component

In order to create job opportunities and to provide poverty and income relief for the low-skilled unemployed, the South African Department for Public Works launched the Expanded Public Works Programme (EPWP) in 2004. The participants are mainly placed in public sector funded infrastructure projects, but also in the environment and culture sector, the social sector, and in non-state projects. During the first phase of the programme (2004-09), 1.6 million work opportunities were created through the EPWP, and in the second phase (2009-14) opportunities increased to 4.3 million. The duration of the job opportunities in the second phase was limited to an average of 65 days. The participants were mainly unemployed individuals with some or completed secondary education, 50% of them being youth and 60% female. The third phase set a target of 6 million workplace opportunities by 2019, focussing the programme more strongly on youth.

The Australian Job Seeker Classification Instrument

In Australia, registered job seekers are allocated to different streams based on their probability of remaining on income support for the following 12 months. This probability is estimated using a wide range of factors that affect an individual’s difficulty in gaining and maintaining employment. These factors are:

Each factor is given a weight, which is used for the aggregation into a final individual score for each jobseeker. Job seekers with higher scores are classified into streams with higher intensity of active labour market interventions.

Ireland’s Probability of Exit Tool

Following the significant rise in unemployment during the Global Financial Crisis, Ireland moved away from its rules-based profiling, which only referred to job seekers to the PES after six months of unemployment, towards a statistical profiling system. The profiling tool estimates an individual’s probability of exiting the unemployment register within twelve months. A job seeker’s probability, referred to as the PEX score, not only depends on personal characteristic, but also on demand-side factors, proxied by geographical location and size of the location. The PEX score is used to classify job seekers as high-risk, medium-risk or low-risk, which determines the types of engagement and intensity of support. PES caseworkers still maintain a high degree of discretion in deciding which activation services to offer.

Source: Loxha and Morgandi (2014[15]), OECD (2012[16]; 2018[17]; 2015[18]), Australian Government - Department of Jobs and Small Business (2018[19]), Barnes et al. (2015[20]).

The non-state part of the EPWP was introduced in the second phase of the programme, and is mainly operationalised through the Community Works Programme (CWP). While CWP is a national programme co-ordinated by the Department of Cooperative Governance, it is implemented by non-profit agencies. The work in the CPW must be useful, defined as contributing to the public good and/or improving the quality of life in communities. The useful work concept is very broad, and contains areas such as food security, community care, support to early childhood development centres and to schools, and community safety. The programme is mainly implemented in rural areas, informal settlements and urban townships. (OECD, 2017[21])

As the EPWP and CWP are able to reach large groups of low-skilled unemployed South Africans, it provides a good opportunity to offer training in addition to work experience. Through funding from the Department for Higher Education and Training and SETAs, the programme already offers training to some of the participants, but this has been fairly limited. CET institutions could offer short-term training programmes to strengthen the skills of EPWP/CWP participants. These skills programmes could be targeted to the skills required in the EPWP/CWP jobs, but could also focus on general basic and employability skills. Including a training component in the EPWP/CWP could help participants to perform better in their assigned jobs, but also in improving their labour market prospects at the end of their EPWP/CWP participation.

Tuition fees could be charged, depending on students’ income

In the current CET system, training programmes are in principle free for students. Nonetheless some of the CET centres charge minimal fees to cover specific costs, such as electricity and photocopying (Land and Aitchison, 2017[22]). As argued by both Land and Aitchison (2017[22]) and the Ministerial Committee on the review of funding frameworks of TVET and CET colleges (2017[23]), tuition fees should be avoided in the CET system, given that the target group generally consists of low-income students.

It could be envisaged that students bear part of the cost of CET programmes, provided that their income is high enough. In that case, a similar system as in TVET colleges or universities could be put in place. Some OECD countries have set up a system in which specific target groups receive vouchers that they can use to pay for training. In Estonia, for example, registered job seekers can access training opportunities through a system of training vouchers (Koolituskaart). These training vouchers have recently also been made available for certain groups of employees under specific conditions. In the case of low-wage older workers and low-skilled workers, the condition to use the training vouchers is that the training has to be related to ICT skills or skills identified as being in shortage by the Estonian Qualifications Authority.

The introduction of income-contingent tuition fees can only happen after a thorough analysis of the characteristics of CET students. If the system only attracts low-income students, setting up a tuition system would be unnecessary. However, if the CET system also attracts a substantial number of higher income students, a carefully designed tuition system could be introduced. It should be ensured that these tuition fees do not constitute a barrier for adults in need of training.

Cooperation with NGOs and social impact investors to obtain additional funding

A host of NGOs are active in South Africa in areas related to community education and training, including skills development programmes for adults and youth, matching job seekers to job opportunities, and career guidance. While they often operate on a small scale, their resources and knowledge could support the development and delivery of CET programmes. The Catholic Institute for Education, for example, operates multiple adult learning centres, which do not only offer basic literacy and numeracy programmes, but also skills programmes (OECD, 2017[21]). Another interesting example is Harambee, which matches young job seekers to employers, providing short skills development programmes when needed.

External donors are funding multiple skills development projects in South Africa, and more funding could be attracted to invest in skills development, including in CET. Social impact investment is increasingly being seen worldwide as a way to mobilise funds to tackle social issues. According to OECD (2015[24]), social impact investment has become increasingly relevant in today’s economic setting as social challenges have mounted while public funds in many countries are under pressure. New approaches are needed for addressing social and economic challenges, including new models of public and private partnership that can fund, deliver and scale innovative solutions from the ground up. Social impact investors seek social and environmental impact from their investments, in addition to financial returns. Education, training and unemployment are key areas in which social impact investment can be mobilised. Vibrant entrepreneurial markets and strong enabling environments are crucial for facilitating this type of investment, as is the capacity to effectively measure outcomes (Wilson, 2016[25]).

Recommended action steps

Table 4.4 provides some possible action steps that could be taken to attract funding to CET from sources such as the unemployment insurance fund, the expanded public works programme and NGOs. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

4.3. Priority funding areas

Poor infrastructure in Community Learning Centres limits their further development

Inadequate infrastructure is often said to be one of the big challenges for the quality, attractiveness and further development of the CET system. Most Community Learning Centres operate from (primary or secondary) school premises and share facilities with the schools. This means that the centres’ operations are restricted by school operating hours (i.e. they can only provide training after school hours, when the facilities are not used for primary or secondary education), but also that many of the facilities are not adult-friendly. This setup restricts the possibility of centres developing into real community centres. While locating Community Learning Centres in schools is not a problem in itself, and there are in fact several benefits to this approach (e.g. efficient use of resources and visibility of CET), the centres should have a dedicated space in schools rather than using classrooms that are used for primary or secondary education during school hours.

It is unlikely that the CET system will be able to have a large enough budget in the short run to build new learning centres in all communities that do not have their own CET infrastructure. A better use of the limited funding would be to improve unused buildings or spare capacity in buildings such as TVET colleges or public libraries.

Expanding the role of CET to also provide vocational skills programmes will require investment in specialised training equipment. In light of the limited budget, but also the fact that the CET system should be flexible and responsive to local needs, investment in expensive equipment that is specific to certain training programmes should be minimised. Instead, CET institutions can enter into partnerships with other training providers (e.g. public TVET colleges, technical high schools, private training providers) and employers who already have the necessary equipment. The Gauteng government, for example, uses the equipment of public libraries for their digital skills programme (see Box 4.1).

If the current CET institutions want to transition into real community centres, some investment will certainly be required to make the centres more attractive. While the existing and potential new funding sources could contribute to these investments, CET institutions should also actively engage with potential donors, such as foundations, international organisations or development cooperation. Funds could be attracted to finance, for example, free Wi-Fi connection in the learning centres.

Recommended action steps

Table 4.5 provides some possible action steps that could be taken to the infrastructure in the CET system. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

More and better trained staff is needed in the CET system

The national public budget for CET is almost entirely reserved for expenditure on compensation of employees. Timely payment of decent salaries for teachers in CET is crucial to attract and retain high-quality teachers (see Chapter 6). Therefore, sufficient funding for teacher salaries should be guaranteed. At the same time, the planned expansion of the system, both in terms of number of students and types of programmes, will require hiring a large number of new teachers. In an expanded CET system, the management of the CET institutions also becomes increasingly important, and management personnel will need to be recruited, as well as support staff.

As CET will gradually be taking up new roles, teachers, managers and support staff will have to learn how to provide these new functions. School managers must learn, for example, how to engage with local stakeholders. Teachers might need to learn how to deliver employability training programmes or vocational skills programmes. The support staff must learn how to register students and how to organise events (such as seminars on life skills). At the same time, lifelong learning becomes increasingly important for school personnel, especially if programmes and services need to be relevant and up to date with community needs. Chapter 6 provides more details on how to ensure the quality of CET staff.

Recommended action steps

Table 4.6 provides some possible action steps that could be taken to ensure that the CET systems has sufficient and well-trained staff. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

Teaching and training materials adapted to the needs of adults need to be developed

Programmes for adults need to be flexible, and allow for part-time and modular approaches that are consistent with other calls on their time. Easing time arrangements and providing flexible alternatives– with recognition of prior learning for example, have been successful in raising participation in several countries. These flexible approaches will also help students that have dropped out at some point to find their way back into the CET system with relatively low barriers. The Mexican basic education programme Model for Life and Work (Modelo Educación para la Vida y el Trabajo) is a flexible programme that allows participants to combine different modules at different levels (see Box 4.3).

As discussed in Chapter 3, teaching and learning materials in CET should ideally be adapted to adults. This is particularly important for literacy and second chance education materials, which are often taken from or based on materials from basic education. Instead, these materials should relate to situations that adults come across in daily life, so that it is directly applicable to their lives. The Kha Ri Gude campaign was able to develop this type of adapted materials. Adult learners do not acquire skills in the same way as children, and research shows that teaching methods that work for children may not do so for adults (German Federal Ministry for Education and Research, 2012[26]) (MacArthur et al., 2012[27]). For example, most adults who want to improve their literacy and numeracy skills already have a range of skills and almost all of them can read or write to some extent (Wells, 2001[28]). Formative assessment, which implies adapting instruction to learner needs by means of regular assessment and tracking learning progress, may be a particularly effective tool for adult learning (see Box 4.4).

TVET colleges or other training providers can share their materials to be used for vocational skills programmes in CET. Similarly, materials from non-formal programmes can be developed following the example from other providers or stakeholders (e.g. from employers providing employability skills training, see Chapter 3).

Digital learning materials provide an opportunity to reach a large group of individuals, provided they have access to digital technologies and have basic digital skills. CET institutions could make digital technologies available to adults who do not have their own computer, tablet or smartphone, and could provide basic digital skills programmes to individuals lacking the skills to use digital resources. Within their Tshepo 1 Million programme, the Gauteng province partnered with Microsoft to make digital resources available for adults to learn how to use Microsoft office software (see Box 4.1). The Mexican basic education programme Model for Life and Work (Modelo Educación para la Vida y el Trabajo) allows participants to complete some of the modules online (see Box 4.3). Evidence from a sample of CET students shows that access to technology is the main feature that students would have liked added to the CET support services (Lolwana, Rabe and Morakane, 2018[29]).

The Model for Life and Work programme (Modelo Educación para la Vida y el Trabajo, MEVyT) in Mexico provides learning opportunities for youth and adults to catch up on primary and secondary education. The programme integrates basic literacy learning with skills training and allows the learners to obtain officially recognised and accredited primary and secondary qualifications. The programme is very flexible, allowing participants to select different modules at the initial, intermediate (primary education) and advanced (lower secondary education) level. The modules cover a wide range of topics, including civic education, language and communication, mathematics and science, social development and citizenship. Some modules also have a focus on the world of work, such as “My business” and “Working in harmony”.

The modular structure of the programme allows learners to design their own curriculum by selecting modules according to their prior skills, needs, interests and the speed at which they learn. This flexibility also allows learners to decide when, where and how they want to learn. Individuals can study on their own or participate in group learning in a community learning centre or a mobile learning space.

To allow for even greater flexibility, an online version of the programme was introduced. Students can participate in a range of modules on an online platform (MEVyT en linea). The platform currently mainly provides the basic modules (i.e. language and communication, mathematics and science) at the intermediate and advanced level, but also a few of the diversified modules (e.g. parenting, the prevention of violence). To help individuals with low digital skills access the online training modules, basic digital skills programmes are offered in community learning centres.

Source: Unesco Institute for Lifelong Learning (2016[30]); Instituto Nacional para la Educacion de los Adultos (2018[31]).

Recommended action steps

Table 4.7 provides possible action steps that could be taken to ensure that the CET system has sufficient and high-quality teaching and learning materials. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

The OECD review Teaching, Learning and Assessment for Adults reviewed available English-language evidence on formative assessment and identified the following good practice elements:

-

Dialogue between teachers and learners: teachers should structure learning as dialogue between themselves and their students.

-

Communication skills: teachers need to evaluate and extend their communication skills, particularly focusing on listening, understanding, asking questions, and giving feedback.

-

Feedback and marking: feedback should focus on the task rather than the person, be constructive and practical, and be returned as soon as possible.

-

Developing an atmosphere conducive to learning: students should feel secure to face challenges and take risks in asking questions that may reveal their lack of understanding.

-

Peer assessment and self-assessment: self-assessment and peer-assessment should be central elements of all learning situations.

-

Collaborative learning activities: discussions and collaborative activities have proven beneficial to many learners.

Source: OECD (2008[32])

A sound administration system is imperative for the functioning of CET institutions

To be able to monitor and evaluate the quality of the CET system, it will be imperative to have strong administrative systems in place that allow to collect information on registered students, completion rates, progression to further education and employment. Measuring the outcomes of training is not only important for quality measurement (see Chapter 6), but also for guaranteeing that training programmes respond to community needs (see Chapter 5). Using digital technology to collect and produce these data can significantly reduce the time and administrative cost allocated to monitoring and evaluation, as well as improve the quality of the evaluation exercises (Unesco, 2016[33]).

Moreover, as the CET system will build strongly on cooperation and partnerships with a wide range of stakeholders, strong administration will be important to formalise partnerships. For example, when a CET institution agrees to use equipment in TVET colleges, this agreement needs to be made official, and this requires sound administrative processes. Chapter 6 discusses how sound administration contributes to CET quality.

Recommended action steps

Table 4.8 provides possible action steps that could be taken to ensure that the CET system has sufficient administrative capacity to perform its tasks. For each action step, the most relevant stakeholders concerned are listed. The list of stakeholders is not exhaustive, and cooperation between different stakeholders is encouraged. The actions steps focus on the short- and medium-term, and a more ambitious action plan could be developed for the longer term in line with the vision for CET from the DHET’s strategic documents.

References

[19] Australian Government - Department of Jobs and Small Business (2018), Components of the Job Seeker Classification Instrument (JSCI), https://www.jobs.gov.au/components-and-results-job-seeker-classification-instrument (accessed on 1 June 2018).

[20] Barnes, S. et al. (2015), Identification of latest trends and current developments in methods to profile jobseekers in European Public Employment Services: Final report, European Commission.

[13] Bhorat, H., S. Goga and D. Tseng (2016), “Unemployment Insurance in South Africa: A descriptive overview of claimants and claims”, Africa Growth Initiative, No. 8, Brookings, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/04_unemployment_insurance_south_africa.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2018).

[12] Department of Higher Education and Training (2016), Investment trends in post-school education and training in South Africa.

[10] Department of Higher Education and Training (2016), Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africa Statistics on Post-School Education and Training in South Africaa, Department for Higher Education and Training.

[11] Department of Higher Education and Training (2011), Annual Report 2010/2011, Department for Higher Education and Training, Pretoria.

[5] DNA Economics (2016), Volume 5: Consolidated Report on the Costing and Financing of the White Paper on PSET, DNA Economics, Pretoria.

[1] FiBS and DIE (2013), Developing the adult learning sector - Lot 2: Financing the Adult Learning Sector, http://lll.mon.bg/uploaded_files/financingannex_en.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2018).

[9] Gauteng Government (2018), Microsoft/ Tshepo1Million Thint’iMillion Initiative.

[8] Gauteng Government (2018), Tshepo 1Million: Primer.

[7] Gauteng Government (2017), Tshepo 1 Million programme profile.

[26] German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (2012), Alphabetisierung und Grundbildung Erwachsener: Abschlussdokumentation des Förderschwerpunktes zur Forschung und Entwicklung 2007-2012, https://doi.org/www.alphabund.de/1861.php.

[14] IDB, WAPES, OECD (2015), The World of Public Employment Services.

[31] Instituto nacional para la educacion de los adultos (2018), MEVyT en línea, http://mevytenlinea.inea.gob.mx/inicio/index.html (accessed on 13 July 2018).

[34] International Monetary Fund (2018), World Economic Outlook - Challenges to Steady Growth, IMF, Washington D.C., http://www.imfbookstore.org.

[22] Land, S. and J. Aitchison (2017), The Ideal Institutional Model for Community Colleges in South Africa: A Discussion Document, Durban University of TEchnology, Durban, https://www.dut.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Community-Colleges-in-South-Africa-September-2017.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2019).

[29] Lolwana, P., E. Rabe and M. Morakane (2018), “Who accesses adult education and where do they progress to? An exploratory tracer study in community education and training”, LMIP reports, No. 37, Labour Market Intelligence Parternship, http://www.lmip.org.za/document/who-accesses-adult-education-and-where-do-they-progress-exploratory-tracer-study-community (accessed on 7 November 2018).

[15] Loxha, A. and M. Morgandi (2014), “Profiling the unemployed: A review of OECD experiences and implications for emerging economies”, Social Protection & Labor Discussion Paper, No. 1424, World Bank, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/678701468149695960/pdf/910510WP014240Box385327B0PUBLIC0.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2018).

[27] MacArthur, C. et al. (2012), “Reading component skills of learners in adult basic education”, Journal of Learning Disabilities, Vol. Vol. 43(2), pp. pp. 108-121.

[23] Ministerial Committee on the review of the funding frameworks of TVET Colleges and CET colleges (2017), Information Report and Appendices for presentation to Minister B.E. Nzimande, M.P..

[2] OECD (2019), Getting Skills Right: Future-Ready Adult Learning Systems, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311756-en.

[35] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2018 Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2018-2-en.

[17] OECD (2018), “Profiling tools for early identification of jobseekers who need extra support”, Policy Brief on Activation Policies, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/employment/connecting-people-with-good-jobs.htm (accessed on 5 February 2019).

[21] OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: South Africa, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278745-en.

[4] OECD (2017), The Funding of School Education: Connecting Resources and Learning, OECD Reviews of School Resources, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276147-en.

[18] OECD (2015), “Activation policies for more inclusive labour markets”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/empl_outlook-2015-7-en.

[24] OECD (2015), Social Impact Investment: Building the Evidence Base, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233430-en.

[16] OECD (2012), Activating Jobseekers: How Australia Does It, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264185920-en.

[32] OECD (2008), Teaching, Learning and Assessment for Adults: Improving Foundation Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264039964-en.

[6] Statistics South Africa (2017), Quarterly financial statistics of municipalities, http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P9110/P9110December2017.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2018).

[3] UNESCO (2017), Ensuring adequate, efficient and equitable finance in schools in the Asia-Pacific region, Unesco Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education, Bangkok, http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en (accessed on 10 September 2018).

[33] Unesco (2016), Designing effective monitoring and evaluation of education systems for 2030: A global synthesis of policies and practices, http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/pdf/me-report.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2018).

[30] Unesco Institute for Lifelong Learning (2016), Education Model for Life and Work, Mexico, http://uil.unesco.org/case-study/effective-practices-database-litbase-0/education-model-life-and-work-mexico (accessed on 13 July 2018).

[28] Wells, A. (2001), “Basic Skills-25 Years on”, Adults Learning, Vol. 12/10.

[25] Wilson, K. (2016), “Investing for social impact in developing countries”, in Development Co-operation Report 2016: The Sustainable Development Goals as Business Opportunities, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcr-2016-11-en.

Notes

← 1. The shortfall amounts to ZAR 16.88 billion in nominal terms, and ZAR 6.447 billion in real terms.

← 2. The OECD projects real GDP growth to reach 0.7% in 2018 and 1.7% in 2019 (OECD, 2018[35]). Similarly, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects real GDP growth to reach 0.8% in 2018 and 1.4% in 2019, much lower than the average of emerging market and developing economies (4.7% in 2018 and 2019) (International Monetary Fund, 2018[34]).

← 3. Following a series of student protests, the decision was taken not to increase fees for students from poor and working-class families in 2016 and cap increases in 2017. The NSF contributed additional funding to TVET colleges and universities to help alleviate the impact of the lower fee collection.

← 4. The SETA grant regulations state that SETAs can only transfer 5% of their uncommitted surpluses to the next financial year. Exceptions can be granted by the Minister of Higher Education and Training. The remainders of the surpluses are transferred to the NSF. Following a court case against the transfer of SETA surpluses to the NSF (by Business Unity South Africa), this part of the grant regulations has been set aside by the Labour Appeal Court in November 2017. SETAs are now no longer expected to transfer their uncommitted surpluses to the NSF, and are urged by the Department for Higher Education and Training to spend all their funds on skills development initiatives in their relevant sectors.

← 5. Of the total UIF assets in 2016/2017, 41.5% were listed as current assets, meaning that they can be converted into cash and operationalised within a relatively short time period (generally less than twelve months).