2. Implications for the Japanese employment system

Japan’s unique employment practices explain to a great extent the existing public policies on adult learning and the general attitudes towards workers’ skills development. Therefore, this chapter presents the distinctive Japanese employment system, with a specific focus on lifetime employment, seniority wage schemes, and regular graduate recruitment rounds. It also discusses the challenges that the system faces due to the structural changes in the labour market, and shows how the system has already been changing in recent years.

The Japanese employment system is characterised by distinctive features that until recently, were widely accepted by both employers and workers. One of the most rooted practices is lifetime employment, which even if it did not cover all workers is a system implicitly guaranteeing many employees, especially those in larger firms, stable work within the same company until retirement. This was linked to seniority wage schemes, whereby workers’ salaries rise with years of service rather than with productivity. Alongside this is the Japanese unique practice of firms’ yearly mass recruitment of new graduates, which relegates mid-career hiring to a secondary role of serving to meet unexpected labour shortages.

Overall, these traditional employment practices have functioned relatively well during Japan’s high economic growth past, when companies took the lead in supporting their workers’ training needs. While still having positive effects on labour market outcomes – such as maintaining youth unemployment rates low – the Japanese labour market is changing, and, with it, the industrial structure and skill needs are also shifting. Both the public authorities and the business sector are gradually embracing shifts in Japan’s traditional employment practices, and several initiatives have been recently put in place to, for example, increase mid-career recruitment or link salaries more tightly to productivity rather than seniority. Even though the core of such traditional practices is likely to remain in place in Japan’s near future, the proportion of full-time male employees in total employment, which has been the backbone of the Japanese workforce to date, is likely to continue to decline. In contrast, the employment of non-regular workers, who are often not covered by employers’ training provision, as well as women and older individuals, who typically participate less to training, will grow. These changes point to the urgency of improving the Japanese adult learning system, especially because in the future it will be more and more difficult to provide adult learning opportunities only through on-the-job training.

The adult learning policy framework of a country depends on its employment norms and practices. For instance, in countries with a strong degree of job protection and low income security in the event of unemployment, both employers, workers and the government might prefer firm-specific training that would help employees remain longer in the same workplace (Estevez-Abe et al., 1999[1]). In contrast, countries with greater job mobility may opt for training alternatives that help workers take greater responsibility for their own training, including in more general training, and thus improve their employability across different companies. Since the period of rapid economic growth that occurred in Japan after the World War II, it has been pointed out that Japan’s employment practices have been characterised by distinctive features such as lifetime employment, seniority wage schemes and periodic mass recruitment of new graduates (Abegglen, 1958[2]; OECD, 1972[3]). As these practices have greatly shaped Japan’s adult learning system, it is important to carefully review them and understand how they have been gradually changing since recent years due to the global megatrends discussed in Chapter 1.

2.1.1. Lifetime employment

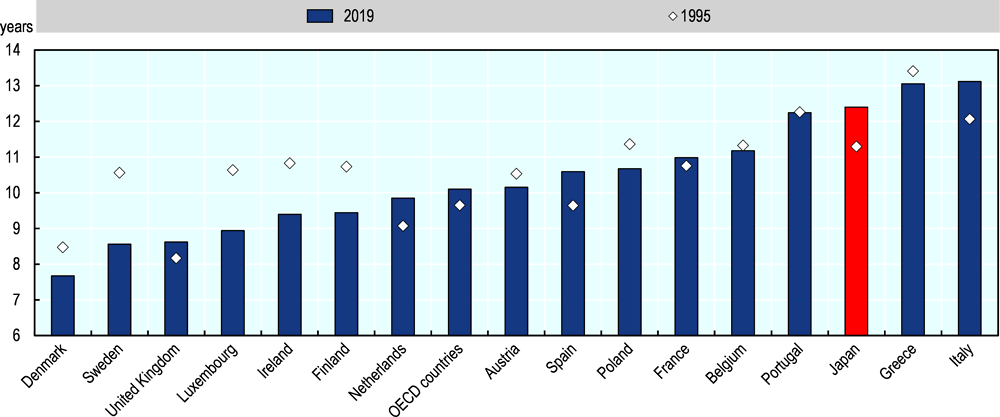

One of the most typical features of the Japanese employment system is the so-called lifetime employment. Under this framework, companies hire new college graduates and implicitly guarantee them stable employment until they reach the retirement age. The consequence of this system is that the average length of service in Japan is among the longest across all OECD countries: 12.4 years in Japan versus an OECD average of 10.1 years in 2019 (Figure 2.1). Against the general OECD trend, figures for Japan have remarkably been increasing in the past years, from 11.3 years of average length of service in 1995, also due to a large increase in the labour force participation of elderly workers. Academic research confirms that both the average length of service and the 10-year retention rate of college graduates with more than 5 years of service have remained high in Japan since 1980 (Kambayashi and Kato, 2016[4]). Such practice of continuously working for one firm has remained strong in the Japanese labour market.

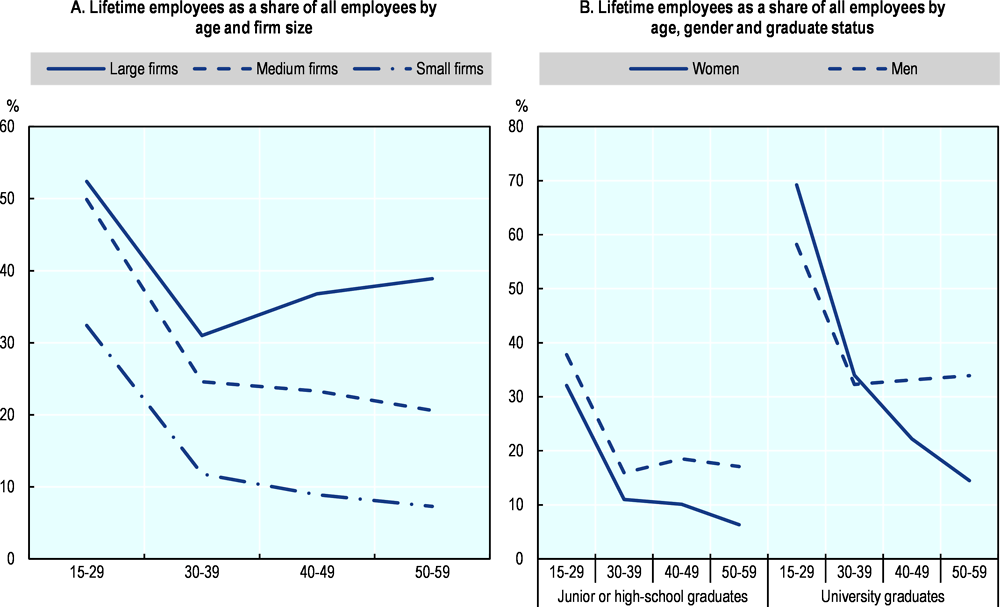

Long-term employment practices are particularly common in large firms. Indeed, around 40% of workers aged 50-59 in large firms have never changed workplace, compared to only 7% in small business (Panel A of Figure 2.2). Similarly, lifetime employment is most prevalent among tertiary educated men. The percentage of tertiary educated women who continue to work for the same firm is about the same as that of men until they reach their 30s. High school graduates have a lower percentage of lifetime employment compared to university graduates in all generations (Panel B of Figure 2.2).

In a labour market based on lifetime employment, workers generally move between various departments and occupations within a company. To allow for broad and flexible placement of workers in the company’s roles, job descriptions are typically not defined in details. However, such vagueness in the contents and responsibilities of a position implies that employees may have to carry out tasks that are not directly related to their primary occupation. As a result, workers tend to be mostly generalists, hence being able to perform a wide range of tasks, rather than specialists in a particular occupation (Ono, 2016[6]). In this situation, worker’s adult learning is more likely to occur informally through on-the-job training, and the content of the training are firm-specific.

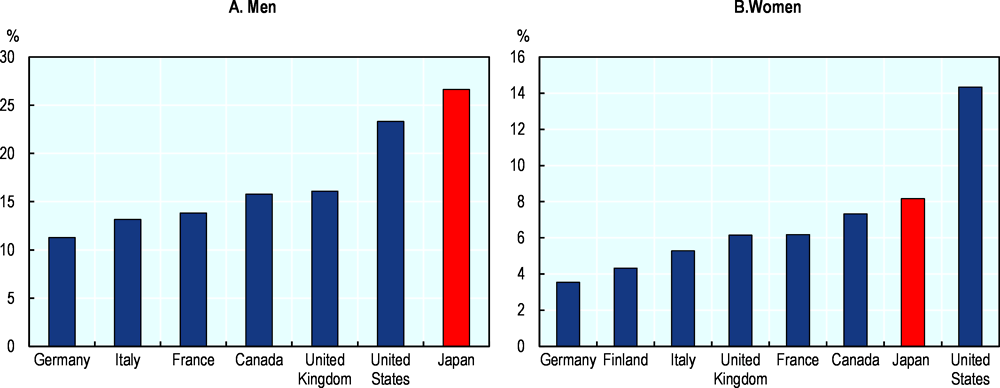

Another feature of the Japanese employment system is that workers generally have long working hours, and the fact that job descriptions of regular workers are typically left vague should also be considered at the core of this culture of long working hours (Ono, 2018[7]). Indeed, as shown in Figure 2.3, the percentage of workers working more than 48 hours per week in Japan is among the highest in G7 countries, especially for men. Such long working hours do not allow much time for off-the-job training, thereby being a major obstacle to training participation, as discussed in Chapter 4.

Under the lifetime employment system, adult learning has been primarily provided by firms. In particular, full-time male workers had little need for training outside the company, as promotions within companies were typically offered by acquiring skills through firm-specific training. In addition, the practice of long working hours have further reduced the incentive to participate in training outside the firm (see Chapter 3 for a discussion on the coverage of the adult learning system in Japan).

2.1.2. Seniority wage structure

Closely related to lifetime employment, the seniority system is a pay structure in which a worker’s wage rises with years of service. In general, wages are paid below the worker’s productivity in younger years and above the worker’s productivity later in their career. By taking a long-term view of human resource development, Japanese companies aim at fostering a sense of organisational unity as well as the efficient formation and accumulation of business-specific skills. As a result, the seniority system attempts to discourage workers to leave the company while ensuring that their productivity is commensurate with their overall productivity on average across their working lives (MHLW, 2013[8]). From the workers’ perspective, instead, the system has the advantage to provide job security and income stability, which in turn alleviate social anxiety.

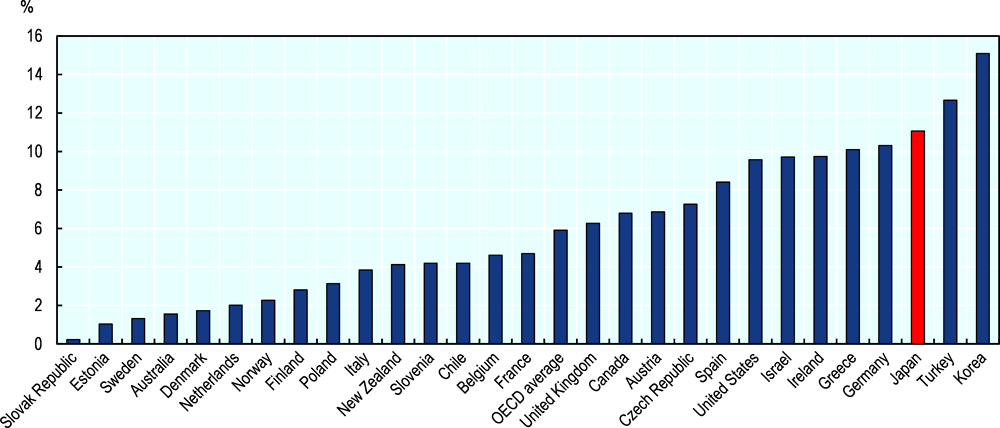

Figure 2.4 shows that the wage premium of working continuously in the same company in Japan is large in comparison to other countries. When a worker’s length of service increases from 10 to 20 years, wages increase by 11%, controlling for skills and other characteristics. This wage growth is the third highest after Korea and Turkey. While, as discussed below, the prevalence of the seniority-based wage system from a macro perspective is gradually declining nowadays, it will most likely remain a feature of the Japanese labour market for many years to come.

Mandatory retirement at relatively young age has also been a feature of Japan’s long-term employment practices. This has risen over the years and currently mandatory retirement is not permitted before the age of 60 years old, i.e. after the age of 60 years old, there is no guarantee that workers in lifetime employment schemes can continue in the same type of employment status as before. However, in response to the rising longevity of the Japanese people, since 2006, companies have been required to ensure that workers remain employed at least until the age of 65. Since 2013, Employers need to choose one the following options to secure the employment of older workers: (1) raise the retirement age to 65 years old in their labour contracts, thereby applying to all employees; (2) re-hire specific all workers at the age of 60 until 65 under a new contractual form (including non-regular employment) if a worker requires, which may also involve a substantial cut in pay; (3) abolish the retirement age. Currently, many older people change their employment status from full-time to part-time after reaching retirement age, thereby facing significant wage cuts and more precarious jobs (OECD, 2018[5]).

In response to an ageing population, the Japanese Government has recently amended the Act on Stabilization of Employment of Elderly Persons to promote the employment of workers beyond the age of 65. The new legislation passed in 2020 and going into effect in 2021 will require companies to take active measures to secure the employment of elderly workers between the age of 65 and 70 through a variety of options, including outsourcing contracts for older workers between companies. In the midst of these changes, offering learning opportunities at later stages of one’s lifetime is key to ensure that elderly workers can remain employable.

2.1.3. Periodic mass recruitment of new graduates

Another feature of the Japanese employment system which is linked to the practice of lifetime employment is the regular mass hiring of new graduates. Under this system, many large organisations recruit students who are about to graduate in batches each year, while hiring mid-career workers remains only a supplementary measure to meet the firm’s needs when it is unable to recruit new graduates or when more workers leave than expected. This is a unique Japanese practice of recruitment, which establishes a job market for new graduates that is separate from the mainstream labour market. Indeed, according to the 2013 Global Career Survey of college graduates between the ages of 20 and 39 conducted by Recruit Works Research Institute, 81% of college graduates in Japan found their first job after graduation while still in school, compared to 46% in the United States, 58% in Germany, and 42% in Korea. Although this system makes it possible for companies to streamline recruitment, selection, and training, it can also distort the job market, as it allows new graduates to find a job immediately upon graduation, even if they lack the required skills. Moreover, those young individuals who are left out from the system (including those not attending university) tend to find it difficult to obtain stable employment.

In times of economic stability and labour force growth, Japan’s distinctive employment practices have had several benefits, such as low youth unemployment rates, stable livelihoods for workers, and a substantial sense of organisational unity. As shown by a survey undertaken in 2016 by JILPT among 8 000 individuals, Japanese workers themselves confirm their preference for such long-term employment practices, with 60% of employees preferring to work for one company throughout their entire career (JILPT, 2016[9]).

However, there are also several limitations of these typical Japanese employment practices. First, it is worth noting that they do not apply to all workers, thereby creating internal disparities. As only full-time workers in larger firms benefit from lifelong employment, there is a large wage gap between regular workers and non-regular workers. Typically, since companies’ priority is to protect the jobs of regular workers with long-term employment practices, non-regular workers have often served as a buffer for employment adjustments when firm growth has stalled (Asano, Ito and Kawaguchi, 2011[10]). The slowdown in economic growth since the 1990s has made companies more cautious about hiring full-time workers, leading to a surge in non-regular employment. As a result of such increase, the disparity in treatment between regular and non-regular employment has become apparent, with job conditions and treatment (including training) being more generous for full-time employees who benefit from lifetime employment than for part-time employees.

Moreover, as Japanese companies have wide authority over human resources, permanent employees are often considered to be obligated to accept a change in work location or duties and overtime work, and they generally think that they cannot refuse a transfer or overtime request (Tsuru, 2019[11]). For this reason, women in their 30s and 40s, who are in the age of child-rearing, are more likely to exit the labour market (see Panel B of Figure 2.2).

In addition, while companies’ practice of hiring in bulk upon graduation has contributed to low unemployment rates among youth, if young individuals are unable to enter full-time employment immediately after graduating from school, it becomes difficult for them to get the job they want in the labour market. The situation is so widespread that Japan also coined a new term – “employment ice age generation” (Shushoku Hyogaki Sedai) – to identify those young people who graduated from school during 1993-2005 and who had more difficulty finding a job than other generations. In particular, the share of full-time employment at age 30s among the “ice age generation” men is about 10% lower than the one of older cohorts (Cabinet Office, 2020[12]), which implies that fewer adults can now access learning opportunities through companies’ training than older generations.

Finally, when career opportunities within the company are plentiful and the employer is committed to job security, the external labour market gets smaller and workers prefer to take advantage of career opportunities within the company by investing in company-specific skills, as it has indeed been the case in Japan in the past (Aoki, 1988[13]). However, the current and forthcoming changing skill needs make it difficult to acquire competences easily in such a situation where labour mobility is low and in-house training is the norm. According to a 2010 study by Talent Strategies, while training internal staff to fill key positions is nowadays a major part of firms’ talent-management strategy for 78% of respondents in Japan, only 24% of firms expect this to be the case in five years’ time. This is indicative of the fact that, in the current changing industrial structure, it is becoming more difficult to recruit talent only within companies (Economist Intelligence, 2010[14]).

These Japanese traditional employment practices have been developed over a long period and both employers and workers in Japan commonly accept them. However, in recent years the government has made efforts to remove the negative effects resulting from these employment practices, leading to changes in workers’ and employers’ behaviour. First, in 2018, Japan enacted a new employment reform aiming at reducing long working hours and narrowing the gap in work conditions between regular and non-regular workers. This is the first time in Japan’s history that overtime regulations with penalties have been introduced, capping overtime at 45 hours per month and 360 hours per year. In addition, in order to ensure fair working conditions regardless of employment status, unreasonable treatments (in, among others, basic salary and bonuses) between regular workers and non-regular workers within the same company have been banned.

From the perspective of promoting mid-career hiring, in 2018 the government also formulated the “Guidelines for Promoting Job Change and Reemployment regardless of Age”, aiming at creating flexible labour markets where workers are more likely to change jobs regardless of their age. The document includes basic principles that companies should consider in order to promote the hiring of people changing jobs (re-employees). In addition, a revision of the labour law made in 2020 now requires large companies to announce quotas of mid-career hires. This aims to promote job matching by revising Japan’s employment practices, which are especially deeply rooted among large companies, and encourage companies to provide information on mid-career hiring to those who wish to change jobs to improve their careers.

In the past years, the share of people changing job has been increasing, apart from a decline during the global financial crisis, reaching as high as 5.2% (3.51 million) in 2019 (Panel A of Figure 2.5).1 Such growth suggests that the recent improvement in Japan’s economy and labour market has led to an increase in the number of people looking for better jobs.2 In addition, there has been a trend rise in the share of workers in the core working age group 25-54 who want to change job, despite some decline linked to the financial crisis. This trend rise was more pronounced for those in the older age groups of 55-64 and 65+ (Panel B of Figure 2.5). This further corroborates the importance of increasing skills development opportunities as a result of increased job change activity, especially for older workers as discussed in Chapter 5.

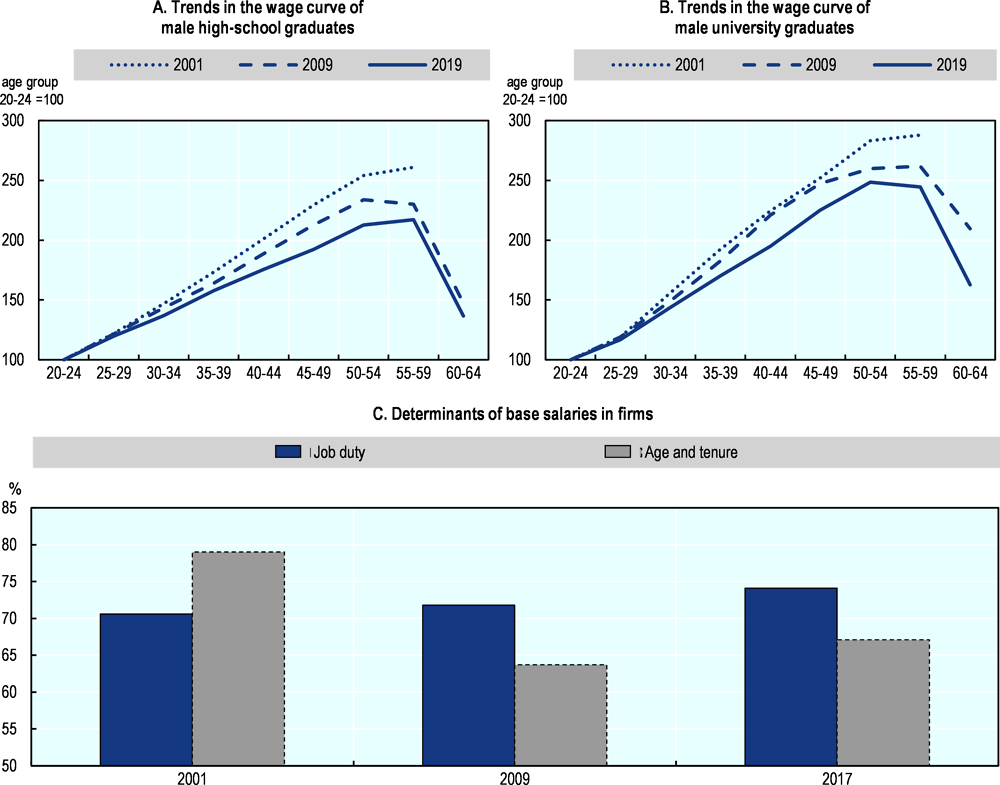

There is also evidence that the importance of Japan’s seniority-based wage system has declined over time. The increase in wages growth with age for both high-school and university graduates is currently smaller than in the past (Panels A and B of Figure 2.6). This may be partly a result of the implementation of the 2006 Senior Employment Security Act – which mandated firms to secure employment possibilities of workers until the age of 65 and might have therefore caused them to reduce the profile of wage increases with tenure to pay for these extra years. In any case, such trends indicate that the Japanese employment practice of increasing wages with age has weakened at a macroeconomic level.

In addition, with respect to the factors that fix salaries, the percentage of companies that consider job duties to determine wages has remained relatively stable, while the percentage of companies that base their decisions on age and years of service has declined compared to 2001 (Panel C of Figure 2.6) (OECD, 2018[5]). This is confirmed by recent data by the Japan Productivity Center, which conducts an annual survey of listed companies to determine the status of their wage systems. According to this survey, the share of companies that have introduced a wage system linked to job duties for managers is as high as 79% in 2018, an increase of 29 percentage points from 2001. The proportion of companies introducing such system for non-management-level employees has also increased by 25 percentage points between 2001 and 2018.

Indeed, employers themselves are slowly accepting changes in Japan’s traditional employment practices. Keidanren, an employer association consisting mainly of large Japanese firms, announced in its 2020 report that existing hiring methods should be diversified, combining more actively the conventional hiring of new graduates in batches with mid-career recruitment. Keidanren also suggested a shift from company-led training to workers’ autonomous career development, as well as a change in the wage system from automatic salary increases based on age and years of service to wages that reflect the evaluation of performance (Japan Business Federation, 2020[15]).

While reform to employment practices that have been shaped over a long period of time requires careful action from the perspective of worker stability, the intensifying competition for talent, changes in skill needs, and prolongation of working life, require a change in mind-set. As a result, in 2018 the Japanese Government launched a new initiative which provides subsidies to companies establishing a pay scheme based on workers’ competences rather than on seniority. In order to receive a subsidy, employers are required to establish their personnel evaluation system and submit it to the local labour bureau for approval. The plan must focus on workers’ vocational ability, competencies, and outcomes. Employers can receive an additional subsidy if they achieve a reduction in turnover (1% for firms with 301 employees or more), an increase in total wage costs of at least 2%, and a productivity increase of at least 6% after three years. Supporting the proper application of this new subsidy and the circulation of good practices is therefore key to weaken the rigid relationship between wages and age in Japan’s labour market.

All in all, against Japan’s traditional employment practices, the employment of non-regular workers, who are often not covered by employers’ training provision, as well as women and older individuals, who typically participate less to training, are growing. As a result, it becomes a priority for the government to increase access to adult learning opportunities and make adult learning more inclusive, especially because in the future it will be more and more difficult to provide adult learning opportunities only through on-the-job training.

References

[2] Abegglen, J. (1958), The Japanese Factory: Aspects of its Social Organization.

[13] Aoki, M. (1988), Information, Incentives and Bargaining in the Japanese Economy.

[10] Asano, K., T. Ito and D. Kawaguchi (2011), Why has part-time employment increased?.

[12] Cabinet Office (2020), Japan Economy 2019-2020.

[14] Economist Intelligence, U. (2010), Talent strategies for innovation: Japan.

[1] Estevez-Abe, M. et al. (1999), Social Protection and the Formation of Skills: A Reinterpretation of the Welfare State.

[15] Japan Business Federation (2020), Report of the 2020 Special Committee on Management and Labor Policy.

[9] JILPT (2016), Survey on Ways of Working.

[4] Kambayashi, R. and T. Kato (2016), “Long-Term Employment and Job Security over the Past 25 Years”, ILR Review, Vol. 70/2, pp. 359-394, https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916653956.

[8] MHLW (2013), White paper on the labour economy 2013.

[5] OECD (2018), Working Better with Age: Japan, Ageing and Employment Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201996-en.

[3] OECD (1972), OECD Reviews of Manpower and Social Policies: Manpower Policy in Japan, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[7] Ono, H. (2018), “Why Do the Japanese Work Long Hours?”, Japan Labor Issues, Vol. vol.2, https://www.jil.go.jp/english/jli/documents/2018/005-03.pdf.

[6] Ono, H. (2016), Why are Japan’s working hours not decreasing?.

[11] Tsuru, K. (2019), To restructure the employment system.

Notes

← 1. Although the Japanese Labour Force Surveys before 2001 use different method, thereby requiring caution in using them for time trends, the 2019 figure of number of job changes remains the highest even as far back as 1984.

← 2. According to the Japanese Labour Force Survey, the number or respondents claiming to change jobs “to find a better job” has been on the rise since 2013, with 1.27 million in 2019, the highest number on record since 2002.