copy the linklink copied!3. DI in Chile

This chapter presents a summary of DI provision in Chile according to the framework explored in the preceding chapter.

The chapter starts by looking at the foundations for identity in Chile in terms of existing national identity infrastructure, the policies supporting DI and Chile’s governance mechanisms.

In the second section, the existing model of DI in Chile is looked at in terms of its technical approach. The policy levers and adoption for Chile’s DI are assessed in light of the legal and regulatory framework, funding and the enforcement measures, the services made available, and the enablers and constraints identified in Chile as well as the intentions around putting citizens in control of their data, the openness with which performance is being shared and the approach to assessing impact.

Finally, the chapter ends with the plans Chile have for expanding ClaveÚnica

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

copy the linklink copied!DI in Chile

Chile is at a transition in terms of its approach to DI. Having built on the existing model of demonstrating identity with a physical card, the country launched ClaveÚnica in 2012. This mechanism for proving that someone is who they claim to be when accessing online services is now moving into a further development to extend its functionality and utility with the ambition that it becomes the default mechanism for people to access, and grant permission for access, to their records across the public and private sector. The functionality of ClaveÚnica is intended to allow for:

-

1. Data authentication: the mechanism by which citizens will be identified to access state services and other private organisations

-

2. Data wallet: A store of personal data for citizens which will allow interoperation with institutions on the basis of the access and re-use permissions which a citizen grants on their information

-

3. Advanced electronic signature: Users of ClaveÚnica will be able to sign electronic documents issued by public bodies

-

4. Citizen mailbox: A means by which the state will notify citizens of important information and progress on their interactions with the state

-

5. Web portal eID: a website where citizens can manage access to their data, grant and revoke permissions and update their personal data

This chapter will consider the situation in Chile in comparison to the benchmarked countries and provide a summary of both the ‘as is’ experience and the imagined future. This will provide the basis for the Assessment and Recommendations of this study.

copy the linklink copied!Foundations for DI in Chile

National identity infrastructure

In Chile, the registration of all citizens, Chileans and immigrants, is administered by the Civil Registry Service of Chile (Servicio de Registro Civil e Identificación, SRCeI). The SRCeI issues a physical card, the Cédula de Identidad, which must be carried and is used by citizens travelling inside the country, proving identity at public and private institutions, and for voting. This publicly operated, centralised register of the population provides the basis for the way in which the country is approaching the question of DI. This model is the basis for several countries discussed in this study including Austria, Estonia, India, Korea, Portugal, Spain, and Uruguay.

To complement the physical Cédula de Identidad (with its own number) cardholders are issued two numbers, the Rol Único Tributario (RUT), an identifier for tax purposes, and the Rol Único Nacional (RUN), their number in the national civil register. The RUT is used alongside the card to complete interactions with the Tax Agency and the RUN with public and private sector organisations including the following:

-

Buy or sell property and cars

-

Obtain a Chilean driving licence

-

Open bank accounts

-

Collect loyalty points in shops

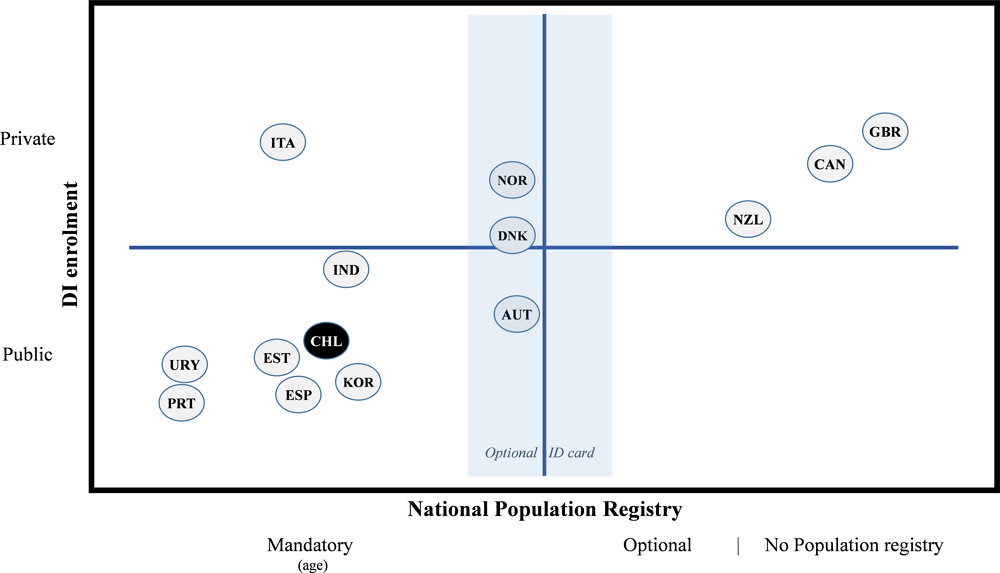

The use of the national civil register means that Chile’s future development of DI has an important foundation. This existing identity, validated by the public sector, affords Chile the opportunity to focus less on working with the private sector to establish and identity and more on working with the private sector to establish interoperability and user experience standards that simplify the identity landscape for citizens in terms of how they access services. Such an approach could build on the experiences of the following countries:

-

Sector specific DI (model 1) as found in Uruguay

-

Sector specific DI (model 2) with a reusable public sector provided identity for private sector services as found in Spain, New Zealand and Portugal

-

The public sector DI (model 5) as the basis for accessing both public and private sector services as found in India and Italy.

-

A shared DI (model 6) where the Chilean government would work with the private sector to develop a single, shared DI built on the national civil register and able to access both public and private sector services as found in Austria, Denmark and the United Kingdom

-

An interoperable DI (model 7) where both private sector DI and public sector DI are built according to standards that allow for public sector and private sector services to be used by either public or privately provided DI as found in Canada, Korea, and Estonia

Characteristics of Chile’s National ID card

The Chilean National ID card contains several of the characteristics laid out in Chapter 2 (see section Dimension 1.1: National identity infrastructure. Characteristics of National ID cards). Chile uses polycarbonate as its material and follows the global standard for identity cards of ISO/IEC 7810:2003 ID-1. The Cédula de Identidad features the following elements:

-

Identification of the country

-

Citizen photo

-

Biographic information including the name, birthdate, nationality, and biological sex of the holder

-

Validity information such as the date of issue, or of expiry and the document number

-

A reproduction of the card holder’s signature

-

A representation of the data contained on the card encoded in a machine readable format, known as the Machine Readable Zone or MRZ. This is augmented by the use of a QR code to verify the validity of the document.

-

Physical card security features including holograms and holographic symbols, embossing, variable colour printing, fluorescent elements, and elements visible only under ultraviolet light.

The Cédula de Identidad contains a microchip format smart card which holds biometric data in a photograph and a right thumbprint of the holder.

This all contributes to the card having three layers of security:

-

Level 1: security elements that can be seen by observing the card

-

Level 2: elements that can only be seen using tools such as UV lamps and magnifying glasses

-

Level 3: elements that are only visible to experts using microscopes or special reading devices.

Several of the countries considered for this study have identity cards which contain a chip. Estonia and Portugal have chips that require contact to be read, Italy has a contactless chip and Spain and Uruguay have a dual interface allowing for both contact, and contactless, reading of the card.

Enrolment for Chile’s National ID card

Anyone aged over 18 and resident in Chile is required to have a Cédula de Identidad identity card, but it is possible to obtain one at a younger age if so desired. This mandatory requirement is matched by the experiences of Austria, Estonia, India, Korea, Portugal, Spain, and Uruguay. Citizens have to pay a fee of 3 280 Chilean Pesos (EUR 4.27) for their card which is cheaper than any of the countries surveyed for this study.

To obtain the document for the first time citizens must attend an office of SRCeI and complete the process in person. This is to ensure the security and authenticity of an application for the identity card by the provision of physical documentation and the capture of biometric data. Appointments for this process can made by telephone or online.

Should a citizen need to renew, or replace, their card whilst they are abroad then this is possible using the number of the Cédula de Identidad or the RUN.

This contrasts with the experience of Austria, Spain, Estonia, Italy, India and Uruguay who all handle part of this application process online, Portugal which has developed an entirely digital approach. Nevertheless, these countries have also maintained an analogue enrolment process, recognising that services should be digital by design rather than digital by default to ensure access for all.

DI policy

Some parts of the Chilean public sector have existing DI approaches for enabling their services to be accessed online but one of the obstacles to the transformation of the citizen experience has been processes which usually require the use of a physical ID card as a starting point. As a result, the majority of services in Chile must still be completed face to face through the ChileAtiende network or the physical locations of other government service providers.

The launch of ClaveÚnica in 2012 was a direct response to this challenge and reflects the current model for DI in Chile. The administration of ClaveÚnica involves both SRCeI and DGD and uses the identity infrastructure discussed above to provide citizens with a single DI based on a username and password that complements the physical ID card which citizens already possess. However, it is not the only DI approach within the Chilean government with there being other competing approaches provided by different parts of the Chilean public sector.

Nevertheless, President Piñera gave ClaveÚnica a clear mandate in his Presidential Instructive on Digital Transformation (Instructivo presidencial sobre Transformación Digital) (Government of Chile, 2019[1]) :

“…los servicios públicos en sus plataformas digitales de trámites o servicios sólo podrán utilizar la ClaveUnica como instrumento de identificación digital, para las personas naturales, reemplazando cualquier otro sistema de autenticación proprio des respetivo órgano de la Administración.”

"…public services in their digital platforms of procedures or services may only use the ClaveUnica as an instrument of digital identification, for natural persons, replacing any other authentication system proper to the respective body of the Administration.”

More recently, the role of ClaveÚnica has been restated through the Presidential Instructions on Digital Transformation of January 24th 2019 (Presidente de la República de Chile, 2019[2]). This is in addition to DI being one of the six lines of action identified in the Government’s Digital Transformation Strategy (MINSEGPRES and DGD, 2019[3]). The ongoing need to redesign services has shown that challenges have existed around adoption, however the Presidential Instructions created a roadmap for more than 300 central government institutions to progressively incorporate ClaveÚnica as its only authentication mechanism for citizens by December 31, 2020. This will not be a minor undertaking as there are 1307 procedures of 3,537 that need an authentication mechanism (37%). Of the 1307, only 477 use Unique password (37%) and the remaining 830 procedures use another authentication mechanism (63%). (see more detail in the section later in this chapter on Chile’s DI platform).

As with the majority of countries considered in this study Chile has made DI, and specifically ClaveÚnica, a fundamental part of their Government’s Digital Transformation Strategy so that the revitalised model for identity can:

1. Improve user experience and allow for greater personalisation of services through Mi ChileAtiende

2. Provide digital access to government services

3. Increase security

4. Transform the digital economy (including private sector services)

5. Reduce the cost of doing business in the country

Whilst it is important to establish a mandate for governments to adopt DI, it is equally important to ensure that citizens have confidence in the security and usability of the DI model. One important factor in achieving this is the role of national digital security strategies to ensure the DI model is secure for government and its users. Another important aspect is the ways in which citizens are in control of their data and it is therefore encouraging to see the intent for the future development of ClaveÚnica to provide digital tools that allow them to grant, and revoke, permissions for its use, reflecting the experience of Austria amongst others.

Chile does not currently have plans to expand the use of their DI to those who live outside the country in the way that Estonia has done through its e-Residency project.

DI governance

As underlined previously in this study, the leadership and development of politics, policies and processes governing DI is critical to its success. Although there is a Presidential mandate for ClaveÚnica it is not yet the single mechanism for authentication and validation in Chile. Because identity is such a critical enabler to the digital transformation of governments it is often the case that multiple institutions will have taken their own approaches to implementing DI. This is particularly found in the experience of the organisations responsible for taxation and Chile is no different with the Chilean tax office (SII) (Servicio de Impuestos Internos) has an established model for identity and provision of online services. Alongside any organisation specific DI models there are two actors involved in leading the implementation and development of approaches to identity in Chile:

-

The DGD within MINSEGPRES is responsible for the country’s broader digital transformation including the Government’s Digital Transformation Strategy (MINSEGPRES and DGD, 2019[3]). In supporting the digital transformation of the Chilean state DGD provides guidance, consultancy and technical support to the teams delivering on the future vision for services in Chile

-

SRCeI administers both the existing identity infrastructure and previous efforts for the digital transformation of identity in Chile, including the original implementation of ClaveÚnica. SRCeI has previously commissioned the Universidad de Chile to consider how it might transform the experience of identity in Chile.

Both actors work together to operationally implement DI in Chile and develop ClaveÚnica. SRCeI maintains the process of validating the identity of citizens and their enrolment into the platform, and DGD is responsible for delivering the authentication and interoperability service of ClaveÚnica, managing the technological infrastructure that allows citizens to identify themselves and interact electronically.

Chile is currently discussing whether there should be an additional actor created to oversee the governance and provision of DI in terms of protecting personal data. Whilst Law No. 19,628 effectively regulates data protection there is not currently a third party acting as a decentralised technical body for the supervision, surveillance and protection of the rights enshrined in the Law or with the authority to regulate, supervise, prosecute and, ultimately, punish breaches of it. As Chile explores how to create this capacity it is nevertheless important for such an entity to be independent of government whilst also ensuring anyone implementing a DI solution recognise and reflect on broader questions of data protection.

It could be attractive to locate all those working on questions of identity management within the same organisation to ensure that there is a focal point for both policy and delivery around identity whether analogue or digital. The countries in this study have approached the political leadership for identity in different ways with Italy, Portugal, the United Kingdom and Uruguay choosing to locate it closely with the head of government, Estonia, Korea, New Zealand and Spain maintaining ownership by the ministries responsible for Internal Affairs or the Interior Ministry, Canada and Denmark the Finance Ministry, and Austria, India and Norway with those responsible for digitalisation. Common to each of these approaches is a recognition that identity policy requires the authority and mandate of a central authority with cross-cutting responsibility for transforming the public sector. Furthermore, each of the approaches places identity management in the same organisation as digital government.

The current separation in Chile is not ideal, especially as DGD does not currently play the leading role in the design and implementation of this key enabler. Nevertheless, the Presidential Instruction on Digital Transformation on January 24th 2019 identified that DGD would have the lead responsibility for leading the implementation of DI for citizens executing the necessary coordination and delivery actions. This recognises the key role of the DGD in supporting the operationalisation and deployment of some of the key enablers for digital government in the country, but weakens its full ownership of the design and conceptualisation phase.

This is important because Chile currently reflects the sector specific DI approach shown in Figure 3.1). However, unlike the simplicity of that model which suggests a single private sector DI and a single public sector DI, ClaveÚnica is in fact only one of several authentication mechanisms within either government, or the private sector. This means that for the citizen there is a proliferation of approaches to identity that will need to be rationalised or consolidated to deliver on the promise of DI for Chile and to enable partnerships with the private sector that transform access to services.

The majority of countries in this study have adopted models that allow for DI to be used across both public and private sector services and there are clear benefits from pursuing an approach to the design of the solution which favours interoperability and reuse across both domains. The existing analogue identity model in Chile allows for the use of the Cédula de Identidad in accessing private sector services and the future vision for ClaveÚnica recognises the same potential. Forging partnerships with the private sector to ensure that the way in which the Chilean government approaches identity has mutual benefits in transforming services and supporting adoption is clearly to be preferred. Such an approach will require strong governance and effective delivery to realise its potential.

DI models that serve the public sector only have more straightforward governance arrangements due to avoiding operability with external private systems and regulating the user experience of those private solutions. However, models which do not promote cooperation between the sectors are consequently limited in their levels of reuse and adoption. Therefore, approaches which reuse existing (public or private) DI, develop shared models, or consider public and private sector applications are preferable.

With the strength of SRCeI, the Chilean government’s commitment to an interoperable ClaveÚnica and the familiarity of the Chilean public with the Cédula de Identidad models 2, 5, 6 and 7 which focus on the reuse of a public or shared DI are best suited to further exploration in Chile.

copy the linklink copied!Chile’s technical DI solution

DI platform

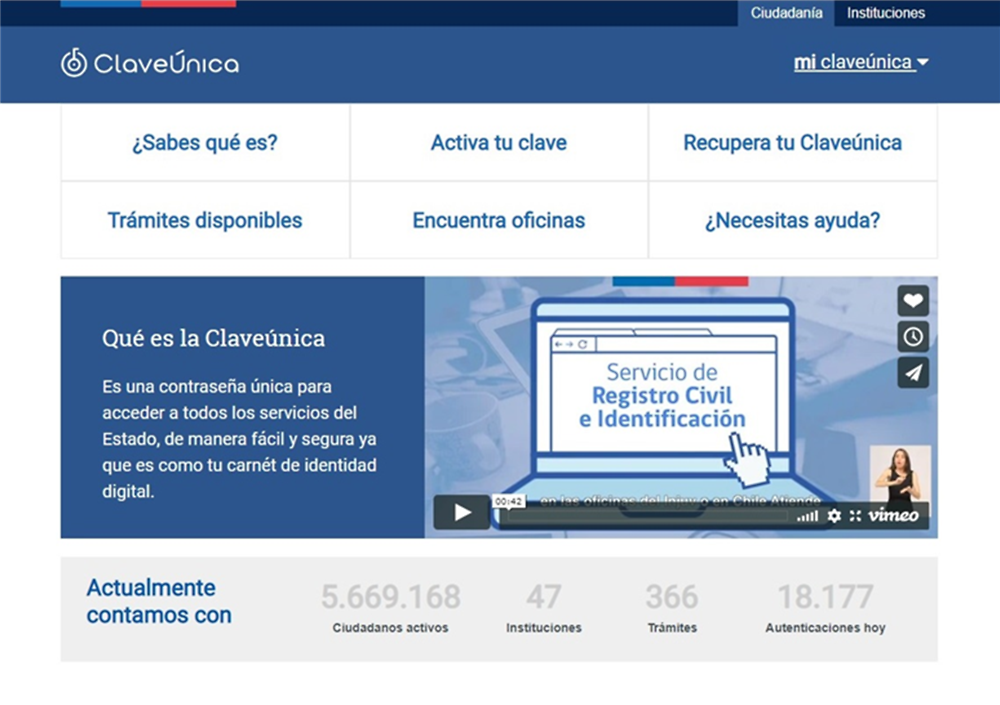

The platform for DI in Chile is ClaveÚnica. The current iteration of ClaveÚnica offers a straightforward web authentication model using a user identifier and password for browser based services. It is built on the underlying identity mechanisms of the Cédula de Identidad provisioned by SRCeI. ClaveÚnica enabled services are is also available through kiosks located within ChileAtiende locations.

Enrolment for ClaveÚnica requires any citizen over the age of 14 to attend an office of SRCeI with a valid Cédula de Identidad and request a ClaveÚnica activation code that will be emailed to them. Once that activation code has been received then they visit claveunica.gob.cl and use that with their RUN to create a unique ClaveÚnica password.

In this situation the verified identity on which ClaveÚnica relies and the product itself is provided by SRCeI. The DGD is responsible for identity policy, adoption of ClaveÚnica and the broader cross-government thinking about the opportunities and value of DI.

Although ClaveÚnica is currently only offering browser based authentication, the future ambition is intended to allow for (as referenced earlier):

-

1. Data authentication: the mechanism by which citizens will be identified to access state services and other private organisations

-

2. Data wallet: A store of personal data for citizens which will allow interoperation with institutions on the basis of permissions which a citizen grants on their information

-

3. Advanced electronic signature: Users of ClaveÚnica will be able to sign electronic documents issued by public bodies

-

4. Citizen mailbox: A means by which the state will notify citizens of important information and progress on their interactions with the state

-

5. Web portal eID: a website where citizens can manage access to their data, grant and revoke permissions and update their personal data

The future technical approach for ClaveÚnica is to be built on OpenID Connect and use the OAuth 2.0 framework. This means that ClaveÚnica is highly interoperable and consists of a lightweight infrastructure that does not require extensive funding to support and maintain. Such an approach favours the adoption of ClaveÚnica in both the public and private sectors.

In providing only simple authentication ClaveÚnica does not currently offer the means of providing additional attributes which expand the scope of how the DI is used. This contrasts with the experience of Austria, Italy, and Portugal where their DI provides access to attributes including tax information, address, birthdate, and professional information. However, the vision for the ClaveÚnica platform is that this simple model will evolve to support the transformation of services in ways that move beyond simple authentication and basic digitisation of analogue processes.

Smartcards

The Cédula de Identidad is an important part of the DI solution in Chile. It is a smartcard and holds biometric data in the form of a right thumbprint of the holder and a photograph. In this respect it provides additional layers of security when accessing services in a face to face setting. However, it is not currently being used to offer any augmented functionality in conjunction with ClaveÚnica.

In the case of Portugal, Spain and Uruguay this information allows for them to implement a Match on Card approach to two factor authentication and for the verification that the person with the card is who they claim to be. In Austria, Estonia, Portugal, and Spain, their implementation of a smartcard model provides the basis for identity amongst particular professions where authenticated digital signatures are part of their daily lives.

Nevertheless, smartcard approaches require the holder to have access to physical hardware and be comfortable with the use of the card in this way. It is not as well suited to those who might only be using this enhanced functionality on an infrequent basis. Furthermore, smartcard technology brings with it greater costs than some of the other factors being considered. As well as the overhead of obtaining physical infrastructure to support their use, the item cost of a card is usually borne by a citizen. Austria, Estonia, Portugal, Italy, Uruguay, and Spain all charge for these cards at an average of EUR 24 for an adult, which is significantly more than the current EUR 4.27 charged to Chileans for their Cédula de Identidad.

Therefore several countries, including Austria, have recognised that smartcards may not be the most effective method of mass adoption and have favoured mobile approaches instead. In doing this the DI approach can maintain security, evolve to reflect new technological possibilities and avoid the need for replacing the physical identity cards already held by the population.

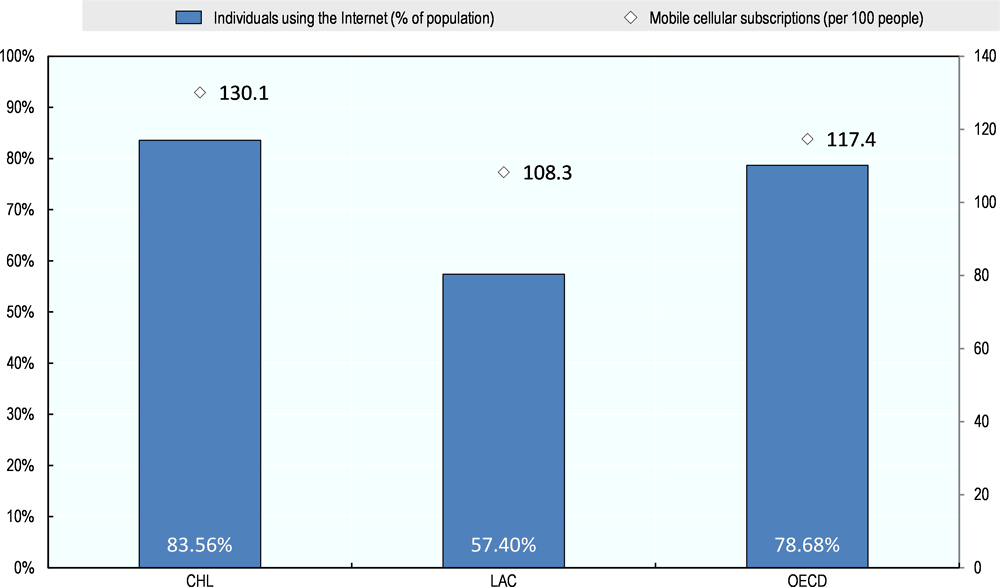

Mobile

ClaveÚnica does not currently require access to a mobile device, it is an authentication mechanism that works regardless of the device being used. This means not only through web browsers on computers and mobile devices but through kiosks located at ChileAtiende too. With figures for smartphone ownership and mobile internet access in Chile higher than the OECD average this could be an important enabler of DI for the country.

From a heightened security point of view, mobile devices have been favoured as a mechanism for providing two-factor authentication in several of the countries included in this study. For Chile, the implementation of a second factor authentication approach using the creation of a One Time Pass (OTP) either through the receipt of SMS or the use of an authentication app on a mobile would be an important addition.

Furthermore, mobile approaches can simplify the application of more advanced security functionality like digital signatures. In Chile, Article 3 of Law 19,799 creates a functional equivalence between an electronic signature and a handwritten signature and mobile offers an attractive opportunity to enhance its utility in any context without the requirement for additional hardware. This is attractive both to infrequent users of the identity, and the providers of services themselves.

Moreover, with the future intent for ClaveÚnica to provide citizens with a data wallet, digital signature functionality and tools for the management of access to data there are obvious benefits to pursuing a mobile first approach.

Biometric and emerging DI

The Cédula de Identidad contains biometric data in the photograph of the holder and the right thumbprint. Nevertheless, ClaveÚnica does not currently use this information to support the delivery of services. Furthermore, the use of the biometric data held within the Cédula de Identidad introduces additional costs to the management of DI in Chile that may not represent good return on investment. As has been seen in the studied countries, the role of biometric data can provide opportunities to use biometric markers in providing higher levels of identity verification and a more coordinated experience of government across digital and analogue services. It is however not a priority in securing broad adoption for either users or providers of services.

The important foundations for identity provided by the Cédula de Identidad and SRCeI as well as the intended architecture for ClaveÚnica favouring interoperability mean that Chile is well positioned to prioritise ‘Bring Your Own Identity’, especially outside the public sector. The models in Figure 3.3 suggested for consideration by Chile all recognise the opportunities for an identity to provide sufficient trustworthiness to be adopted across the day to day experience of the public as an enhancement to email or social media credentials. The experience of Portugal and New Zealand amongst others in seeing their DI reused by telecoms, media and banking is particularly relevant to demonstrating the value of interoperable DI in transforming digital services and replacing the need for face to face service interaction.

copy the linklink copied!Policy levers and adoption

Legal and regulatory framework

Chile’s Government Digital Transformation Strategy identifies DI as one of six strategically important lines of action to support the digital transformation of the Chilean state (MINSEGPRES and DGD, 2019[3]). This follows from President Sebastián Piñera’s first address of June 20th 2018 and the Presidential Instruction on Digital Transformation on January 24th 2019, identifying DI as one of four strategically important lines of action on its state modernization plan (Presidente de la República de Chile, 2019[2]). There is not only a clear statement of political intent in recognising ClaveÚnica as the preferred model for DI in Chile but a comprehensive mandate which requires teams within government to recognise it as such.

Whilst adoption is therefore mandated for service providers in government there is no legal requirement for citizens to be in possession of a DI. This contrasts with the legal requirement for residents over the age of 18 to be in possession of a Cédula de Identidad. This is common in those countries like Chile which have a national identity register and a physical identity card but Chile may wish to extend that requirement to the possession of a DI as is the case in Denmark, Estonia, Korea, and Portugal.

Law No. 19,799 first implemented in 2002 provides the legal basis for the use of electronic signatures in Chile. In Article 3 it identifies the functional equivalence between the act of signing something by electronic signature and a handwritten signature on paper.

Chile is developing data protection legislation to reflect the OECD’s Recommendation on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder flows of Personal Data (OECD, 2013[5]). Law No. 19,628 covers several important areas for underpinning the successful implementation of DI in Chile. They include the principles of:

-

Legality in the processing of data (the use of personal data only with the consent of the holder or Legal provision)

-

Purpose (use of data only for the purposes explicitly indicated)

-

Proportionality (use of data limited to the purpose explicitly indicated)

-

Quality

-

Responsibility

-

Security, and

-

Information (provision of access to policies on data processing)

The existence of this law makes provision for some of the ambitions for interoperability contained within the Government’s Digital Transformation Strategy and an imagined future where the country is able to work in a paperless fashion (MINSEGPRES and DGD, 2019[3]). The development of ClaveÚnica on the basis of open standards reflects a similar opportunity to champion interoperability. In both these cases the Technical Interoperability Standard in the State of Chile is an important document for supporting the implementation of DI and transformed government services.

One way in which the governments of Austria, Canada, New Zealand and Portugal have chosen to enhance their legislative framework in support of interoperability, data protection and DI is to prevent different government agencies from using identical identifiers for the same person. This approach means that any information being stored about an individual by one organisation is not easily joined to information held elsewhere if it is accessed by nefarious actors. The example of Austria’s SourcePIN discussed earlier ensures that only the information which is necessary for a service to meet a need is ever stored.

A further important legal development related to the adoption of the ‘once only principle’ is found in several of the surveyed countries including Denmark and Portugal. The Presidential Instruction on Digital Transformation on January 24th 2019 considers the "Cero Filas" (Zero Rows) policy that mandates government departments not to require citizen documentation that is already in the State's possession, taking the necessary steps to interoperate and access the required information (Presidente de la República de Chile, 2019[2]).

Latin American and Caribbean countries have strengthened their cooperation on digital government, especially through the e-Government Network of Latin America and Caribbean (Red de Gobierno Electrónico de América Latina y El Caribe, Red GEALC) in recent years and are initiating conversations about developing a regional equivalent to the eIDAS regulation seen in the European Union, initially in the context of mutual recognition of digital signatures. Chile is developing a standards based approach to ClaveÚnica that could support cross-border identity but there is no regulatory provision for such an approach. Nevertheless Chile’s recognition of Argentina’s digital driving licence demonstrates the potential for enabling such cross-border services. Achieving regionally interoperable DI would not be a quick undertaking but one which may prove beneficial.

A final area of the legal and regulatory framework which is not currently in place in Chile relates to the interaction between the public and private sectors. The nature of this relationship in terms of the model for identity underpinning ClaveÚnica is still to be confirmed, but as Chile works through its understanding and implementation of the provision of identity, the use of that identity and the reuse of any data associated with that identity this legal and regulatory framework will need to be developed. The experience of the United Kingdom in managing the federated nature of its identity provision may be instructive. By developing several Good Practice Guides the UK set out its expectations for providers of identity in a way that didn’t have legal weight but which established the criteria by which their involvement would be approved or rejected (UK Cabinet Office, UK Government Digital Service and UK National Cyber Security Centre, 2018[6]).

Funding and Enforcement

The commitment in President Piñera’s address of June 20th 2018 and the Presidential Instruction on Digital Transformation on January 24th 2019, plus the ongoing work of DGD and SRCeI on implementing the expansion of ClaveÚnica demonstrate the commitment of funding for this work through the current political cycle (Presidente de la República de Chile, 2019[2]). This sits alongside the ongoing funding for SRCeI and its contribution to the country’s national identity infrastructure. Through the Presidential Instruction on Digital Transformation on January 24th 2019, four axes were established for achieving State modernization, of which one is the implementation of DI for citizens, placing the responsibility on DGD to lead the process and execute the necessary coordination and delivery actions.

One way in which Chile is mitigating this risk is through a standardised model for producing business cases across the public sector. All government technology projects planned for the 2018/2019 period were presented using a common format and going through a review and technical approval process. This review and approval process requires thought to be given to role of DI and the use of ClaveÚnica reflecting the experiences of Denmark, Portugal and the United Kingdom.

Whilst the political imperative has been made clear and DI embedded into the funding approval process there is less detail on the delivery approach and associated support for helping ClaveÚnica achieve its ambitions and the Chilean public sector maximise its benefits. The reorganisation of DGD into four core services includes a focus on a function to facilitate the development and support of shared platforms following the Government as a Platform model. This additional capacity is intended to provide on the ground support and consultancy. The success of these efforts will be seen in the level of adoption they achieve. Whilst ClaveÚnica has received high level endorsement and a mandate for enforcing adoption there remains a need for all those, whether within DGD or SRCeI, involved in the provision of identity services to reflect the same focus of responding to needs as any public facing activities. Therefore, ClaveÚnica should be approached with an approach that starts from the premise of meeting needs well.

Alongside the technical capability to deliver ClaveÚnica as a secure and reliable platform, effort needs to be invested in simplifying its initial adoption so that a minimum of effort is required to implement a solution or persuade a team to adopt. Critical to this success is allowing delivery teams to make use of a shared resource as quickly and easily as possible. These efforts would be supported by thought being given to the role of engagement and account management for ‘customers’ elsewhere in government. Such roles will complement product level user research by helping DGD and SRCeI understand any barriers to adoption and help to augment the way in which ClaveÚnica describes its value proposition, surfaces its technical documentation and frames its associated benefits.

Finally, from an internal perspective, Chile is still developing central resources that provide guidance to shape delivery and setting standards with which to assess the quality of that delivery. It will be important for these service delivery standards and guidelines to consider the role of identity and the design of the services which rely on it.

In terms of encouraging adoption of ClaveÚnica amongst the public there is no explicit intent to seek funding for marketing campaigns. Instead, the team at DGD and SRCeI have expressed their commitment to developing adoption of ClaveÚnica in line with the needs of citizens rather than growing the number of people holding a DI but with limited opportunities to use it. The ChileAtiende and SRCeI networks represent an important element of how Chile is supporting its citizens to make use of ClaveÚnica and to develop the digital literacy of its citizens.

Government services

Transformation of the user experience of government is one of the biggest motivations for implementing an effective model of DI. By being able to rely on a secure and effective DI, citizens are able to meet their needs without having to be physically present. The highest priorities for implementing DI were taxation, education and health.

In Chile, 49% of the nation’s 3 537 procedures can be carried out online. Of those, there are 1307 that need an authentication mechanism (37%). Of the 1307, only 477 use ClaveUnica (37%) and the remaining 830 procedures use another authentication mechanism (63%).. DI is an important priority for enabling the transformation of the citizen experience. In particular the policies of “Cero Filas” (Zero Rows) and “Cero Papel” (Zero Paper) aim to turn Chile into a truly paperless state with institutions committed to digitising services and using ClaveÚnica to support it. In some cases the country is mandating the use of ClaveÚnica to continue to receive benefits, with one case producing increased adoption by 1.5m people in one month.

A second example is Empresa en un dia, a programme making it possible to create a business in a single day. ClaveÚnica adds initial value to this service but in working with the programme it is expanding the offer of ClaveÚnica to include electronic signatures and establish a business focused approach that allows citizens to link their business identity with their personal identity. By meeting several common needs, ClaveÚnica reflects aspects of Government as a Platform thinking that will accelerate the transformation of other services that would otherwise have to develop their own approach.

Whilst the primary focus of DI is initially central government services, more than half of the surveyed countries anticipate the adoption of DI within local governments and other channels, as highlighted in the previous chapter. This is an important area for Chile to consider given the existing landscape of service provision in Chile makes use of the ChileAtiende network as well as physical locations for several other public bodies. Currently the delivery of online or telephone based services is limited by the limited application of DI in Chile and this is a priority for Chile in developing its strategy for service design and delivery.

Chile is following a standards based approach which offers the potential for Chile and its regional partners to emulate the experience of eIDAS amongst the European Union member states in establishing a common, interoperable, approach to identity. The recent development of Argentina’s digital driving licence, which is recognised in Chile is an important demonstration of the potential for enabling cross-border services.

An area that was absent from conversations about the enabling role of DI in Chile was its impact on those working within government. More than half of the countries discussed earlier (Denmark, Estonia, India, Korea, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Uruguay) have prioritised the needs of public servants in their approach to DI. The internal benefits of being able to validate the identity of someone and the ease with which such a solution can be deployed have benefits that should not be overlooked.

Private sector services

Approaches to DI that encourage its use by both government and private sector services increase both visibility and familiarity. This amplifies the relevance of a DI mechanism as citizens use it more regularly than if they were solely limited to its application for public sector services. The reusability and interoperability of a given DI for accessing both government and private sector services adds value to citizens who don’t need to manage multiple credentials or constantly create new accounts to prove who they are.

ClaveÚnica currently enables in excess of 5m Chileans to access services in the public sector but the ambition is for it to expand to incorporate private sector services, including the banking sector. One of the most important developments in that respect is the addition of a second factor of authentication to complement the existing ClaveÚnica mechanism.

With a technical solution built on OpenID Connect and using the OAuth framework the ClaveÚnica solution is highly interoperable and consists of a lightweight infrastructure that does not require extensive funding to support and maintain.

The Chilean private sector is already familiar with reusing the identity infrastructure provided by the Cédula de Identidad and the RUT and RUN identifiers. This provides Chile, and ClaveÚnica with an important starting point from which to consider its wider application.

As discussed in Figure 3.3 there are four models, which would lend themselves to the ambition and context in Chile for building on the country’s existing identity infrastructure to enabler access to private sector services. The experiences of Austria, Denmark, Estonia, India, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom in recognising the potential for DI to enable Business to Consumer (B2C) services provided by the private sector.

Enablers and constraints

The benchmarking study identified six areas – business model, hardware infrastructure, awareness, enrolment, user experience and digital literacy - that have the potential to be seen as an enabler, or a constraint for DI in a country.

For Chile, the business model associated with DI is yet to be formally decided. The country has an existing basis for verified identity in the Cédula de Identidad that is an enabler to the integrity of ClaveÚnica. The technology underpinning ClaveÚnica is designed to enable interoperability with private sector services. Chile has the opportunity to decide how it shapes the business model for ClaveÚnica and its enhanced functionality as it works with public sector and private sector service providers and encourages adoption within the country.

The Cédula de Identidad is a smartcard that requires hardware infrastructure to unlock its most secure features. However, none of that functionality is exploited by ClaveÚnica or the model for DI in Chile and therefore hardware infrastructure is neither an enabler nor a constraint. The relatively high incidence of mobile phone penetration in Chile underpins future ambitions for ClaveÚnica to focus on the opportunities available through web and mobile platforms.

The existing model of identity in Chile means that there is high awareness of processes involving the Cédula de Identidad. This provides a good enabler for adoption of ClaveÚnica. Nevertheless, awareness and adoption of ClaveÚnica will reflect its availability in terms of accessing services that people need. The potential in this area is seen by the example of a service which switched to ClaveÚnica and increased adoption by 1.5m people in one month. The most significant barrier to its usage is the limitations on the number of services which are ClaveÚnica enabled but, as discussed elsewhere, the Presidential mandate to see more services switch to using it should encourage adoption of the current model of ClaveÚnica and provide a boost to later adoption of the planned enhanced functionality.

As with awareness, the enrolment experience for ClaveÚnica benefits from being built on top of the Cédula de Identidad and this should be seen as an enabler. However, the process by which someone obtains a ClaveÚnica is still reliant on a face to face interaction.

Nevertheless, the overall user experience of ClaveÚnica is effective, acting as an enabler for those who wish to use it to access services online or at a ChileAtiende kiosk. As Chile progresses with the channel shift to digital services it is critical that the necessary support is made available for those who might not be comfort using digital channels. The issue of digital inclusion is therefore critical to the adoption of DI.

Whilst the ease of using ClaveÚnica online is relatively straightforward the broader Chile performs reasonably well in terms of access to the internet standing above the LAC and OECD averages in terms of share of the population using the internet and mobile subscriptions per 100 people (Figure 3.5). Given the diverse and complex geography of the country this is an impressive achievement. Nevertheless, the question of digital literacy and access is an important consideration in the adoption of DI in Chile with there being a gap in terms of the population that has access to the internet and the number of individuals who choose to transact with the public sector digitally. Chile’s National Survey of Socioeconomic Characterisation (Encuesta de Caracterización Socioeconómica Nacional, CASEN) found that 30.1% of the population used the internet to complete a government procedure over the last year (MIDESO, 2017[7]).

copy the linklink copied!Transparency and monitoring

Citizen control of their data

Neither ClaveÚnica nor the Cédula de Identidad currently offer a means by which citizens can control their data and see the detail of how their data are being accessed and/or used. However, the future ambition for DI in Chile places this at its heart. With Chile anticipating that ClaveÚnica will provide a data wallet for citizens and a website where permission can be granted and revoked there is particular relevance in the experience of Spain. Carpeta Ciudadana provides a means of seeing an audit trail which includes not just their own login activity but the detail of how organisations have used their data.

Performance data

Certain performance indicators are published on the homepage for ClaveÚnica. These reflect the number of active users, institutions, processes and daily authentications. Although it is important to recognise the importance of the availability of this information, it is not as extensive as some of the other dashboards featured in this study.

Furthermore, it is important for Chile to consider whether these measures are providing the necessary level of information to respond with any changes that might be required to improve the user experience of ClaveÚnica and to address any barriers to adoption. Moreover, as the vision for the future ClaveÚnica is implemented it will be important to track its performance according to relevant and insightful KPIs.

The use of the RUN and reliance on the existing Cédula de Identidad affords the Chilean government an opportunity of establishing a view of services accessed by citizens both online and in person across government. This provides an important source of data for broader service transformation, but must be treated with caution. As discussed previously, Austria, Canada, New Zealand and Portugal have enacted laws that require the disaggregation of data about individuals.

Impact assessment

The majority of countries surveyed as part of this study did not conduct extensive analysis of the impact of their DI approach. There is little evidence that Chile currently carries out a sophisticated approach to measuring the impact of its DI and has not yet made this part of the plans for the future of ClaveÚnica.

Nevertheless, the Study for the Formulation of a Modernization Project of the Civil Registry and ID (Universidad de Chile, 2017[9]) identified several areas in which impact and performance could be measured. These include:

-

The usage of DI both in terms of raw usage and implementation

-

The success of DI reuse between the public and private sectors and interoperability of data that has enabled a reduction in its requesting, processing and storing

-

The impact of DI on the internal operations of the SRCeI and the transition from paper to digital records

-

The transformation of analogue processes experienced by the public and the opportunities for redesigning their experiences

-

The tracking of skills development amongst staff and the public

These highlight the value in understanding performance in order to measure impact, both on citizens in terms of the benefits to their daily lives, but also to the state itself in terms of the transformation of the experience and any efficiency.

References

Chilean Government (2019), ClaveÚnica, https://claveunica.gob.cl/ (accessed on 3 April 2019).

Chilean Government (2019), Presidential Instructive on Digital Transformation, https://digital.gob.cl/instructivo/acerca-de (accessed on 28 August 2019).

MINSEGPRES and DGD (2019), Estrategia Transformación Digital, https://digital.gob.cl/doc/estrategia_transformacion_digital_2019_v1.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2019).

OECD (2013), Recommendation of the Council concerning Guidelines Governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0188.

OECD and ITU (2017), World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators (for cellular mobile subscriptions).

Presidente de la República de Chile (2019), Instructivo Presidencial en Transformación Digital.

UK Cabinet Office, UK Government Digital Service and UK National Cyber Security Centre (2018), Identity proofing and authentication - GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/identity-proofing-and-authentication.

Universidad de Chile (2017), Estudio para la Formulación de un Proyecto de Modernización del Servicio de Registro Civil e Identificació.

World Bank (2016), World Development Indicators (WDI), https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators (accessed on 3 April 2018).

Metadata, Legal and Rights

https://doi.org/10.1787/9ecba35e-en

© OECD 2019

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.