2. Investment policy

This chapter assesses the regulatory regime for foreign investors in terms of barriers to entry and operations, as well as the legal frameworks for investment protection and dispute settlement. It compares Myanmar’s FDI regime against regional peers and a global sample of countries, and identifies a number of policy options for consideration by the authorities for improving Myanmar’s attractiveness to foreign direct investment. It also reviews several core investment policy issues – the non-discrimination principle, protections for investors’ property rights and mechanisms for settling investment disputes – under Myanmar law and Myanmar’s investment treaties. It takes stock of recent achievements, identifies key remaining challenges and proposes recommendations to address them.

The first OECD Investment Policy Review of Myanmar (OECD, 2014) noted the urgency of the former government to reform the investment policy framework. Many laws dated from colonial times, while others were often ill-suited to an open economy and not in conformity with international standards. The investment regime was scattered across multiple laws, in many instances outdated and incomplete. Investment procedures were cumbersome and sometimes unwarranted and some were particularly prone to discretionary abuse by authorities. Myanmar also remained largely closed to foreign investments, being assessed at the time as the second most restrictive economy to foreign direct investment (FDI) according to the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index.

This second OECD Investment Policy Review of Myanmar takes place in a substantially different environment. Many of the policy recommendations made in the first review were instrumental in a series of important reforms implemented subsequently that have significantly improved the investment climate. Myanmar has adopted a modernised investment and corporate framework for both domestic and foreign investors, pioneering explicit investors’ obligations to act responsibly and reducing considerably the level of discrimination against FDI. Although a significant number of sectors are still partly off limits to foreign investors, Myanmar no longer features among the top most restrictive economies under the Index.

Despite considerable progress over recent years, the reform momentum needs to be sustained and even deepened for the benefits of investment reforms to be shared widely and growth to be environmentally sustainable. Only in this way can the positive effects of investment more effectively contribute towards improving the lives of Myanmar people and meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The foundations of an enabling investment environment have been laid to a great extent with the new Myanmar Investment Law (MIL) (2016) and the new Companies Law (2018). New laws concerning intellectual property (IP) rights and arbitration are laudable achievements, as they bring Myanmar’s legal framework broadly in line with international standards in these two important areas. However, a number of challenges for complementary policies and implementation capacity on the ground remain to be addressed. The success of these recent developments in the legal framework also hinges on ongoing efforts to improve the independence and competency of the judiciary and the Myanmar courts, which will have a crucial impact on investors’ confidence in the effectiveness of these new laws in practice.

Myanmar is also at an important juncture in terms of its approach to investor protection in investment treaties. With only 14 investment treaties in force today, Myanmar is in a favourable position to review its approach to investment treaties. Treaties with vague, unqualified provisions may attract undesirable interpretations in ISDS cases and, in some instances, overlap with newer investment treaties with the same partner countries. Overlaps between older-style BITs and newer treaties with the same partners may raise issues of coherence between them which could potentially be exploited by investors to circumvent the newer, more nuanced investment treaties and thereby undermine reform efforts.

This chapter looks precisely at the core investment policy issues – the non-discrimination principle, the degree of openness to foreign investment, the protection of investors’ property rights and mechanisms for settling investment disputes – that underpin efforts to create a quality investment environment for all. It takes stock of recent related reforms and examines the quality of government policies currently in place.

Evaluate the costs and benefits of remaining restrictions to foreign investment in manufacturing sectors with no bearing on national defence and security and that remain partly restrictive to foreign investors due to joint-venture requirements.

Equally evaluate the costs of remaining restrictions to foreign participation in services sectors, such as in financial, construction and retail distribution services, which provide critical backbone services to all economic sectors. All these sectors are largely interlinked with market and efficiency-seeking manufacturing investments that Myanmar aims to attract. Cross-country evidence shows that these restrictions typically add costs to entire value chains, including in manufacturing sectors, by restraining potential competition among services input providers. This not only hinders a country’s investment attractiveness, it may also end up hurting consumers’ choices and purchasing power.

Make sure that foreign investors are capable of registering long-term land leases in accordance with the MIL. For this, the government may want to issue clear instructions and procedures for the relevant land-related agencies to efficiently implement the MIL. Similarly, it should clarify that pursuant to the new Companies Law, Myanmar companies with up to 35% foreign ownership are allowed to own land under the same terms as wholly-owned Myanmar companies. The private sector has reported repeated difficulties in registering long-term leases of foreign investors with the Office of Registration of Deeds, because of the lack of clarity on the relationship of the MIL with the Transfer of Property Restriction Act of 1987 (TIPRA). Similar concerns have also been raised with regards to the relationship of the Condominium Law of 2016 and the TIPRA. The MIL’s provision allowing all foreign investments in Myanmar to obtain longer terms leases (up to 50 years renewable) is one of its main achievements and a key improvement to the business environment. Access to land on a longer term basis is a critical condition for all businesses, especially for infrastructure projects and land-based investments which require debt financing.

Clarify the ‘negative list’ status of the list of restricted investment activities issued by the Myanmar Investment Commission as mandated in Art 42-43 of MIL. This would require strong co-ordination within government but would add great clarity to the investment regime going forward, notably to potential foreign investors. At this stage, there may be little inconsistency between the current list (Notification 15/2017) and applied restrictions, but such a clarification is particularly important to avoid a widening dichotomy in the future. To date, only security services activities seem to be restricted and not listed in the Notification 15/2017, but this inconsistency generates uncertainty as to whether there are more restricted activities that are not listed or whether the list will be constantly updated to reflect changes in underlying regulations.

Do not allow representatives from State-Economic Enterprises to take part in Proposal Assessment Teams involved in assessing projects in sectors and segments related to the SEE operations. The potential conflict of interest arising from their involvement in the process generates uncertainty and might result in non-competitive approval conditions.

Continue to prioritise efforts to establish a functionally independent judiciary and improve legal certainty under the Myanmar court system. These challenges have been consistently identified as some of the most important for Myanmar in its democratic transition. The government should continue to pursue, together with external experts and other stakeholders, initiatives that aim to build trust in the independence of the judiciary, increase resources available for training a new generation of judges and lawyers and promote access to justice programmes at the community level to provide dispute resolution alternatives to the court system.

Design, draft and implement subsidiary regulations to accompany recent laws on IP rights and arbitration. The enactment of these new laws is a laudable achievement. However, dedicated IP courts and authorities to supervise the administration, registration and enforcement of IP rights also need to be established before investors will be able to have confidence in their rights under the new IP laws. Similarly, the government should consider encouraging the development of dedicated commercial courts and building capacity within the judiciary to promote effective enforcement of rights granted under the new arbitration law.

Review and consider possibilities for renegotiation and clarification of older-style investment treaties. These treaties should be calibrated to reflect the appropriate balance of preserving the government’s right to regulate while contributing to Myanmar’s efforts to attract FDI. The government’s experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic may shape how it views key treaty provisions or interpretations as well as the appropriate balance in investment treaties. Vague, unqualified provisions in treaties concluded by Myanmar in the past may not appropriately safeguard the government’s right to regulate and may attract unintended interpretations in ISDS disputes. Some of these older-style treaties also overlap with newer, more nuanced investment treaties concluded with the same partner countries. Myanmar, therefore, may wish to consider taking steps to update these treaties and its approach to future treaty negotiations to ensure the agreements appropriately safeguard the government’s right to regulate. It may be possible to achieve updates to some existing treaties through treaty amendments or joint interpretations agreed with treaty partners. The government may also wish to engage with treaty partners with whom Myanmar has two or more investment treaties in force concurrently to review whether overlapping treaty coverage reflects current priorities.

Manage potential exposure under existing investment treaties proactively. The government should continue to develop ISDS dispute prevention and case management tools. Myanmar may also wish to consider efforts to raise awareness about its investment treaties and the significance of its international obligations under these investment treaties for the day-to-day functions of different government agencies and officials that regularly interact with foreign investors.

At the time of the first OECD Investment Policy Review (2014), Myanmar was the second most restrictive economy to FDI according to the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (Box 2.1). Emerging from years of economic isolation after the government initiated a wide range of reforms to open its economy to foreign trade and investment, investment policy measures in place were still in many ways excessive or unwarranted and some were particularly prone to discretionary abuse by authorities. The relatively poor scoring reflected the myriad legal and regulatory measures that discriminated against foreign investors for economic purposes, as the Index does not take into account any procedural hurdles or national security-based measures.

At that time, the OECD advocated for drastic reforms to Myanmar’s investment regime, including with regards to rules on admission and treatment of foreign investors. Investment is critical to spur growth and sustainable development and international investment can sometimes provide additional advantages. Beyond bringing additional capital to a host economy, FDI can help to improve resource allocation and production capabilities, can act as a conduit for the local diffusion of technological and managerial expertise such as through the creation of local supplier linkages, and can provide improved access to international markets (OECD, 2015). The earlier Review also advocated for the adoption of rules encouraging responsible business conduct by domestic and foreign investors in Myanmar (see Chapter 4), recognising that investments may involve negative externalities and that businesses should abide by the highest RBC standards to avoid or mitigate any harm that may arise from their or business partners’ and suppliers operations.

The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index seeks to gauge the restrictiveness of a country’s FDI rules. The FDI Index is currently available for almost 80. It is used on a stand-alone basis to assess the restrictiveness of FDI policies in reviews of candidates for OECD accession and in OECD Investment Policy Reviews, including reviews of new adherent countries to the OECD Declaration.

The FDI Index does not provide a full measure of a country’s investment climate since it does not score the actual implementation of formal restrictions and does not take into account other aspects of the investment regulatory framework which may also impinge on the FDI climate. Nonetheless, FDI rules are a critical determinant of a country’s attractiveness to foreign investors and the Index, used in combination with other indicators measuring various aspects of the FDI climate, contributes to assessing countries’ international investment policies and to explaining the varied performance across countries in attracting FDI.

The FDI Index covers 22 sectors, including agriculture, mining, electricity, manufacturing and main services (transport, construction, distribution, communications, real estate, financial and professional services). Restrictions are evaluated on a 0 (open) to 1 (closed) scale. The overall restrictiveness index is a simple average of individual sectoral scores.

For each sector, the scoring is based on the following elements:

the level of foreign equity ownership permitted;

the screening/approval procedures applied to inward foreign direct investment;

restrictions on key foreign personnel; and

other restrictions, e.g on land ownership, corporate organisation (branching).

The measures taken into account by the Index are limited to statutory regulatory restrictions on FDI, typically reflected in countries’ negative lists under FTAs or, for OECD countries, under the list of exceptions to national treatment and other official OECD instruments. Measures are also identified through legal research undertaken in conjunction with OECD Investment Policy Reviews and yearly monitoring reports.

The FDI Index does not assess actual enforcement and implementation procedures. The discriminatory nature of measures, i.e. when they apply to foreign investors only, is the central criterion for scoring a measure. State ownership and state monopolies, to the extent they are not discriminatory towards foreigners, are not scored. Preferential treatment for special-economic zones and export-oriented investors is also not factored into the FDI Index score, nor is the more favourable treatment to one group of investors arising from international investment agreements.

Source: For more information on the methodology, see Kalinova, Palerm and Thomsen (2010). For the latest scores, see: www.oecd.org/investment/index.

Since then, Myanmar has made significant strides to liberalise its foreign investment regime. It no longer features as the second most restrictive under the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, although a significant number of sectors remain partly off limits to foreign investors. The broad picture is, nonetheless, encouraging as the government seems to remain committed to reducing excessive or unnecessary restrictions on foreign investment moving forward.

In this respect, the government should consider continuing with the liberalisation of FDI in key sectors. Special attention could be given to removing remaining restrictions to foreign investment in manufacturing sectors with no bearing on national defence and security and that remain partly restrictive to foreign investors due to joint-venture requirements. The government may also consider advancing with reforms in financial, construction and distribution services, which provide critical backbone services to all economic sectors. All these sectors are largely interlinked with market and efficiency-seeking manufacturing investments that Myanmar aims to attract. Empirical evidence suggests that FDI restrictions in services typically add costs to entire value chains, including in manufacturing sectors, by restraining potential competition among services input providers. As such, they not only hinder a country’s investment attractiveness, they also end up hurting consumer choice and purchasing power (OECD, 2018a; Nordås and Rouzet, 2015; Rouzet and Spinelli, 2016).

The government may also want to clarify the status of the ‘negative list’ of restricted investment activities issued by the Myanmar Investment Commission as mandated in Art. 42 and 43 of the MIL. Currently, this list is enshrined in Notification 15/2017. Giving this or a reformulated list a status of ‘negative list’, meaning that all activities that are not explicitly listed there would be open to investment in compliance with applicable regulations, would add great clarity to the investment regime moving forward, notably to potential foreign investors, although this would require strong upfront co-ordination within government.

At this stage, there may be little inconsistency between the current list (Notification 15/2017) and applied restrictions, but such a clarification is particularly important to avoid a widening dichotomy in the future. To date, only security services activities seems to be restricted and not listed in the Notification 15/2017, but this inconsistency generates uncertainty as to whether there are more restricted activities that are not on the current list or whether new inconsistencies may emerge in the future. For instance, if new restrictions or investment conditions are introduced and not reflected in the list.

The benefits of investment policy reforms implemented so far are beginning to bear fruit more widely and may provide additional support for the government to press ahead with further liberalisation. FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP have been on a rising trend since 2011, and FDI into manufacturing sectors has picked up considerably, increasing from about 5% of foreign investments up to 2012-13 to roughly 14% in 2018-19 according to statistics from DICA. These investments contribute to furthering economic diversification, job creation and the development of better employment opportunities.

Furthermore, as reported by the World Bank (2018a), reforms implemented since 2011 have accelerated capital accumulation and productivity gains, which are estimated to have been the main drivers of economic growth in the post-liberalisation period. Their estimates suggest that total factor productivity was responsible for almost half of the growth realised over 2010/11-2015/16, followed by capital accumulation (39%). FDI has played a major role in supporting these economic transformations. This growth pattern is similar to that of China, Cambodia and Viet Nam in their respective post-liberalisation periods, and reflects Myanmar’s rapid structural transformation and growing integration with the world economy.

The telecommunications sector is perhaps the most notable example of the potential impacts of FDI liberalisation, notably when adequate frameworks are in place. Prior to the reform, access to fixed and mobile telephony in Myanmar was among the lowest in the world, with a mobile penetration rate of only 14%. Access to internet was even more insignificant. After the opening of the sector to private and foreign participation the situation changed dramatically. Currently, the level of mobile penetration has already reached 100%, with the rate of smartphone penetration reaching roughly 80% (World Bank, 2019).

Myanmar has significantly removed restrictions to FDI over the past years

Recent reforms have considerably reduced barriers to entry and discriminatory treatment of foreign investors (Figure 2.1), bringing Myanmar’s investment regime much closer to international levels of FDI openness, as measured by the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index. Nevertheless, the current regime still maintains a considerable number of discriminatory measures and restrictions to FDI. The progress achieved since 2014 – notably if compared to the level of restrictions observed across ASEAN economies – is commendable. The number of sectors where foreign investors are required to operate through joint ventures with domestic investors, for instance, were significantly reduced during the period, from 94 to 22 sectors, and a number of sectors previously closed were opened to FDI, such as insurance, banking, wholesale and retail. Currently, the level of FDI restrictiveness is comparable with the average level of non-OECD economies included in the Index, and significantly below the ASEAN average.

Perhaps even more importantly, the new investment framework brought considerable clarity to foreign and domestic investors about the applicable rules and provided a more level playing field for foreign investors. Besides narrowing the extensive list of sectors in which foreign investment was previously either prohibited or restricted, the new law also provided for non-discrimination safeguards and brought foreign and domestic investments – once regulated by separate laws – under the same regime, reducing the possible scope for discriminatory treatment in the future.

The investment approval process was also streamlined under the new law. The previous approval system was complex and sometimes opaque and the burden to investors and the administration was considerable (OECD, 2014). Among other weaknesses, the approval process was all-encompassing, generally covering investments of all sizes in a broad range of sectors and activities without any consideration to their potentially different risks and profiles; it was also lengthy, involving multiple bodies and requiring multiple approvals in some cases; the approval criteria were complex and in some cases beyond the administration’s assessment capacity; and there was considerable room for abuse of discretion by the Myanmar Investment Commission (MIC), both in terms of the approval system for investment and the conditions that could be attached to individual projects.

The new investment approval regime is much more in line with best international practices. It now applies similarly to both domestic and foreign investors, and its scope and procedures have been narrowed down and simplified. The scope of projects requiring an approval by the MIC has been expressly defined in the law and its implementing regulation as follows: i) projects considered strategic to the Union; ii) large capital-intensive projects where investment is expected to exceed USD 100 million; iii) projects having a large potential impact on the environment and the local community; iv) businesses which use state-owned land and building; v) and businesses which are designated by the government to require the submission of a proposal to the Commission, such as for projects spanning across the national border or across states or regions, as well as projects using land above 100 acres or 1000 acres in the case of agricultural projects.

In addition, some investments may only be carried out with the approval of the relevant ministry as stipulated in the List of Restricted Investment Activities (Notification No. 15/2017). The criteria for approval have also been streamlined and publicised, including in relation to requirements by line ministries. All other projects are exempt from investment approvals, needing only to comply with the relevant regulations for conducting the business. At their discretion, projects falling outside the scope of the MIC approval requirement may apply for an endorsement of the Commission (or its relevant state or regional office for investment capital amounts up to USD 5 million) in order to enjoy benefits relating to rights to use land and investment incentives as stipulated in the Law on Investment and implementing regulations.

The new approval framework also obliges authorities to act according to pre-established timeframes of up to 90 working days for the entire approval process, as stipulated in the Myanmar Investment Rules (Notification No. 35/2017), although some flexibility is provided for authorities to suspend or extend such timeframes in specific cases (e.g. investor delays in providing required additional information or because of complexity and novelty of the proposal).

As a result, the time required to obtain a MIC permit has gone down from roughly 90 days and 8 procedures under the previous framework, although in reality it often took about 6 months to a year (Frontier Myanmar, 2018), to 40 days and 4 procedures under the new regime (DICA, 2019a). The simplified endorsement procedure is subject to shorter statutory timelines (60 days). Similar results are also observed in relation to registering a company under the new Companies Law and its online portal MyCo. Prior to such reforms, the World Bank’s Doing Business indicator showed that it took 72 days and cost about 157% of the income per capita of Myanmar to start a business in the country. In 2020, subsequent to the implementation of the online MyCo portal, starting a business can now be done in 7 days (in a few hours in the simplest cases) and the associated cost is estimated at about 13% of the income per capita (see Chapter 3 for more information).

There is still room for improvement nevertheless with respect to MIC permits and endorsements. For example, stakeholders have reported that representatives of State-Economic Enterprises are sometimes present at Proposal Assessment Team meetings, at which investors make a briefing about their projects and clarify any queries the authorities may have. The PAT team is responsible for deciding on whether a proposal can be submitted for MIC approval or not, and if it requires modifications before being allowed to proceed to MIC approval. There is clearly a potential for conflict of interests associated with the participation of SEE representatives at these meetings. This generates uncertainty and can be detrimental to competition if conditions attached to approving proposals end-up erecting inefficient barriers to entry.

There have also been concerns about the application of Art. 64(d) of the Myanmar Investment Rules by which the Commission shall consider, when assessing the investor and investment proposal, whether or not the proposal and the investor demonstrate a commitment to carry out the investment in a responsible and sustainable manner. Stakeholders consulted during this review have reported that the MIC typically requires the investors to commit to spend 2% of profits in corporate social responsibility activities. There is no guideline on what sort of activities qualify as CSR for this purpose.

Despite the authorities’ well-intended objectives, this practice is detrimental in many ways to the objective of encouraging responsible investments. First, it reinforces the idea that ‘positive’ actions parallel to business activities, such as philanthropic actions and even sometimes simple compliance with laws and regulations, are a legitimate way to compensate for any harm caused by businesses to the environment, labour and local communities. This is non-educative at the minimum. Secondly, and more importantly, it does little to prevent malpractices and abuses by investors, including because there is no proportionality of such expenditures, and often no link whatsoever, to the potential costs and negative externalities of the business activity (see Chapter 4 for an in-depth discussion and recommendations of how Myanmar can better promote responsible business conduct).

Oddly, some manufacturing activities remain partly off-limits to foreign investors

For a number of reasons, countries worldwide have long opened non-security-related manufacturing sectors to foreign investment. This is typically allowed without any form of discrimination, except when a horizontal measure applying across the board is in place, such as screening or restrictions on the acquisition of land for business purposes by foreign investors. Very few countries still maintain some sort of explicit discrimination against foreign investment in manufacturing.

Myanmar is an exception in this regard. It still restricts the participation of foreign investors in some manufacturing activities by either requiring them to invest jointly with domestic investors, in which case the minimum direct shareholding or interest of a Myanmar Citizen Investor in the joint venture is 20%, or prohibiting their participation altogether (Table 2.1). The scores are also slightly increased by a horizontal restriction on the access to land by foreign enterprises, who are only able to access land on an inequitable leasehold basis, whereas local firms are also able to access land on a freehold basis. Although this is not widely the case giving the rarity of freehold land, the methodology does not take this into account.

The pervasiveness of such restrictions in Myanmar widely contrasts to the experiences in other parts of the world, including within ASEAN economies (Figure 2.2), although it is worth noting that investments within special economic zones are exempted from the purview of the Law on Investment and its implementation rules. The economic implications of such restrictions would probably be more limited if domestic producers of such goods faced competition in import markets, but this is not entirely the case. Myanmar has historically erected barriers to trade and many of these goods are still not allowed to be freely imported into the country, featuring among the 4 613 tariff lines still requiring import licences under the current Import Negative List (Notification No. 22/2019 of the Ministry of Commerce).

With a few possible exceptions, the list of prohibited or restricted manufacturing activities can hardly be considered strategic enough to justify any particular protection from the state. The maintenance of such high entry barriers to FDI serves most likely to insulate domestic groups from competition and force linkages with interested foreign investors or simply ensure that domestic interest groups share in the rents of such projects. In Myanmar, such vested interests may additionally come from the numerous state economic enterprises (SEEs) that still operate in related manufacturing markets (Rieffel, 2015). If the case, a future opening up of such sectors to foreign investment should be contemplated together with the possibility of privatising related SEEs.

The exercise of control over operations is one key underlying characteristic of foreign investment by multinational firms (Hymer, 1976; Grossman and Hart, 1986) and forced joint-venture requirements may restrict their ability to fully exercise such control and influence the distribution of a project’s ex post surplus. In addition, foreign investors may be reluctant to enter into a joint venture with local investors, especially when it is difficult to find suitable local partners with the required capacity and skills. Among other things, issues of weak corporate governance and lack of transparency, as well as home-country sanctions impeding investors from transacting with ‘specially-designated individuals and companies’, as in the case of US persons, may play a role in this. In certain environments, foreign joint venture partners may also have incentives to deploy older technologies and production techniques than used in the industry frontier if they believe the risks of technological leakage is high (Moran, Graham and Blomström, 2005).

As such, restrictions may deter investments in the restricted sector, as well as in other activities relying on their inputs. By potentially constraining competition in such markets, they may affect consumers’ choice and purchasing power and may, in some cases, have even larger environmental and health externalities. One example is the beverages industry, particularly alcohol, where foreign investment in manufacturing and distribution is subject to joint ventures and imports were banned until May 2020, with few exceptions. The result was the development of counterfeit and illicit trade of alcoholic drinks, with potentially larger public health risks and loss of government tax revenues.

Moving forward, the government may want to revise this forced joint venture policy in non-strategic manufacturing sectors by relying on other, less distortive alternatives to achieve intended public objectives. Non-discriminatory regulations can be used to mitigate potential negative externalities, and encouragement of good corporate governance and advanced investment promotion and SME development activities may support the formation of genuine and more efficient joint ventures, alliances and linkages between foreign and domestic investors (see Chapters 3 and 7 for more information about policies that can support such objectives).

Remaining barriers to FDI in services sectors have economy-wide productivity implications

The service sector offers immense opportunities to improve the livelihoods of Myanmar’s citizens, typically playing a major role in absorbing part of the structural shift in employment and economic value arising from the agricultural exodus. In addition, it plays an increasingly intrinsic role in manufacturing activities, whether domestically-oriented or part of regional and global value chains (GVCs).

Manufactured goods have likely never been as service-intense as they are today. In OECD economies, services inputs already account for slightly more than half of the value of manufacturing exports (Miroudot and Cadestin, 2017). Services are contributing to value-added generation in manufacturing industries both upstream, by helping to improve productive efficiency with, for instance, more competitive logistics and financial services, and downstream by facilitating product differentiation with, for instance, digital product extensions and complementary services and digitals distribution and aftersales services.

The development of efficient services markets depends to a great extent on having a pro-competitive domestic regulatory environment behind the border. But the liberalisation of FDI entry plays an important complementary role. For practical purposes, the latter is the focus of discussion here. Market access policies share more commonalities across sectors than behind the border issues that may be highly sector-specific.

As mentioned above, Myanmar has considerably reduced barriers to FDI in recent years. A number of such reforms impinged on services sectors that were once shielded from foreign competition and which were subsequently opened completely or partially to foreign investment. This was the case, for instance, of telecommunications, banking, distribution and transport services.

More recently, the government also liberalised foreign investments in insurance services. A first opening came already with the enactment of the Myanmar Companies Law, which allowed up to 35% of foreign participation in a Myanmar company before being considered a foreign company, although this policy had not yet been implemented until recently by line authorities. Then, in early 2019, the government further liberalised FDI in insurance activities by allowing the entry of up to three foreign life insurers through wholly-owned subsidiaries (Announcement No. 1/2019 by the Ministry of Planning and Finance). In addition, foreign investors were also allowed to invest in life and non-life insurance businesses as Myanmar companies or through joint ventures in which foreign interests do not exceed 35%. As of March 2020, foreign investment in companies listed on the Yangon Stock Exchange was allowed, up to foreign shareholding limits if any stipulated at the discretion of the companies and subject to approval from the relevant authorities.

Beyond insurance, the banking sector has also been further liberalised recently. Along the same lines as the insurance reform, the Central Bank of Myanmar issued, in January 2019, Regulation No. 1/2019 permitting foreign banks and other financial institutions to hold up to 35% of equity in a Myanmar bank. Consequently, the measure opened up the retail banking market to foreign participation up to that limit. Banks with foreign shareholding beyond the 35% threshold will be allowed to engage in retail banking in January 2021 according to the Central Bank announcement of 7 November 2019. In late 2018, the CBM had already reinitiated a wave of liberalising reforms with the issuance of Directive No. 6/2018 allowing foreign bank branches to provide banking and financing to local firms in both foreign currency and kyat, at par with local banks. Previously, foreign bank branches were only allowed to engage in wholesale banking and export financing activities to foreign-invested entities and local financial institutions, and they were fully prohibited from engaging in retail banking services.

Despite this, in addition to remaining restrictions in insurance and banking sectors, foreign investment remain prohibited or limited to joint ventures with any local entity or any Myanmar citizen in the following services activities:

Construction, sales and lease of residential buildings, except if under a build-operate-transfer agreement with the government where 100% foreign ownership is permitted;

Real estate investment: foreign investors are allowed to own up to 40% of the total floor area of registered condominiums;

Securities firms, in which the foreign shareholder may not control and hold more than 50% of the shares in a licensed securities business;

Retail activities in mini-market, convenience store (Floor area must be above 10 000 square feet or 929 m2);

Construction for fish landing site, fishing harbour and fish auction market;

Publishing and distribution of periodicals in ethnic languages including Burmese;

Tour-guide service, including travel agency services; and

A few other niche service activities.

Some of these activities might entail considerable economic costs by shielding domestic investors from foreign competitive pressures. The conditions imposed on foreign engagement in retail activities, for instance, seem fairly stringent (the minimum floor area requirement is large for supermarkets within a city for instance), possibly protecting relatively large domestic retail groups in addition to SMEs in the sector. An evaluation of the costs of maintaining the current restrictions in key backbone services sectors in place, such as retail distribution, construction, banking and insurance, would shed light on whether such restrictions are still relevant and effective in achieving their public purpose. Excessive protection of domestic services industries may be detrimental to other downstream industries and consumers who may have to pay more for quality-equivalent services.

With all the recent reforms, the government may also want to update the list of restricted investment activities in order to reflect the most up-to-date regulatory environment and increase the legibility of the investment regime to investors. As mentioned above, at this stage, there may be little inconsistency between the current list (Notification 15/2017) and applied restrictions, but clarifying the ‘negative list’ statue of the list is particularly important to avoid a widening dichotomy in the future.

Access to land and real estate by foreign investors remains particularly difficult

The fragmented nature of the land framework (see Chapter 8) adds an additional layer of complexity for foreign investors to navigate through. The different land laws contain uneven restrictions on transfers of land to foreign investors. Only certain types of land can actually be leased to foreign investors and many require specific permissions (Table 2.2).

In addition, pursuant to the Transfer of Property Restriction Act of 1987 (TIPRA), foreign investors are not allowed to acquire immovable property rights by way of purchase, gift, pawn, and exchange or enter into leases which exceed one year, nor are they entitled to acquire immovable property by way of mortgage without special government permission. While it is relatively common worldwide for foreign investors to be subject to more strict regulations on access to and ownership of agricultural land and, to a lesser extent, of land for business purposes and real estate investment, it is rather unusual to impose such a short lease term period.

The MIL and the SEZ Law were a great advancement in the regulatory business environment in Myanmar in this respect. The MIL allows foreign investors to extend a land lease term to up to 50 years with the possibility of two additional extensions of 10 years each upon obtaining a MIC permit or endorsement approving a Land Rights Authorisation for the project by the Myanmar Investment Commission. The SEZ Law equally allows foreign investors located inside the zones to enter into long-term leases up to 50 years, extendable for another 25 years. Alternatively, foreign investors may partner with or invest up to 35% in a Myanmar company to make a land-based investment under the same conditions of domestic investors.

Foreign investors have also been allowed, pursuant to the 2016 Condominium Law and 2017 rules, to purchase up to 40% of the ‘saleable floor area’ of a condominium building. This refers to six-floor or more residential buildings with an area of at least 20 000 square feet and standing on land registered as ‘collectively owned land’. While this represents an important market liberalisation, some implementation challenges remain.1 In respect to foreign investors, practitioners have called attention to the unaddressed inconsistencies between the Condominium Law and the TIPRA. The new condominium regime does not explicitly state that it prevails over the TIPRA, although it can be assumed so given its explicit recognition of foreign ownership rights; nor does it clearly specify if foreign legal persons and natural persons are equally entitled to acquire condominium units or whether these rights are limited to natural persons only (Stephenson Hardwood, 2018; Lincoln Legal Services, 2018).

In general, the application of the TIPRA is still confusing and unclear in relation to property holdings by foreigners. This has proved problematic even in situations where the applicable regime seems much clearer, such as for leases of land to foreign investors in accordance with the Myanmar Investment Law (MIL). The MIL clearly states that it prevails over other laws and as such long-term leases to foreigners should be possible for MIC-permitted or endorsed projects. But practitioners report that obtaining some of the required government approvals for leases of property to foreigners can be very difficult and even once obtained, it may prove challenging to fold them into a transaction because concerned government agencies sometimes disagree in the application of the law. They have reported the unwillingness of the Office of Registration of Deeds (ORD) to register long-term leases due to policy disagreements about whether foreigners should be able to lease land or due to the lack of clear instructions and procedures for doing so. This has been a major hurdle to infrastructure and land-based investment projects in Myanmar, which typically rely on debt financing.

Investment policy reforms have likely resulted in more inward FDI than expected

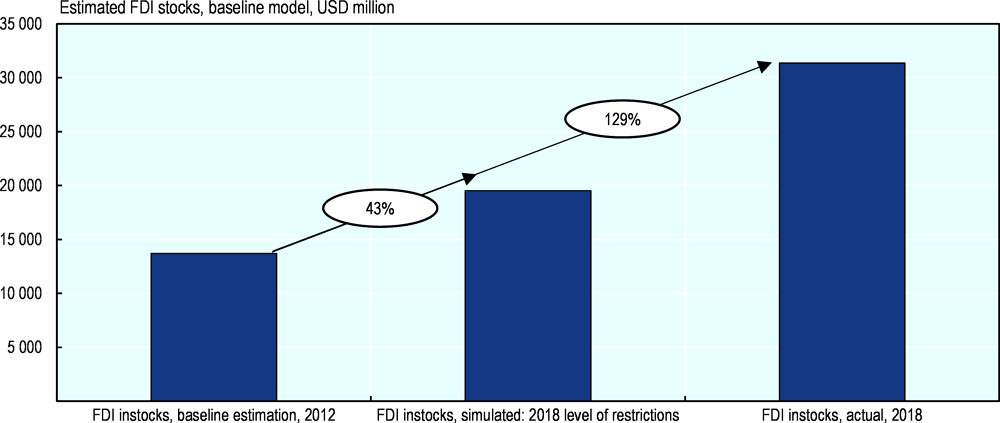

Recent OECD research shows that the introduction of reforms leading to a 10% reduction in the level of FDI restrictiveness, as measured by the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, could increase bilateral FDI inward stocks by around 2.1% on average across countries (Mistura and Roulet, 2019). An illustrative simulation exercise, drawing on the baseline model relying on data up to 2012, suggests that Myanmar has possibly benefited more from reforms to its investment regime than what would have been predicted.

The model suggests that, all else held equal, Myanmar’s bilateral FDI stocks would be expected to be 43% higher if it carried out the implementation of reforms bringing down FDI restrictions to the current level observed in 2018 as measured by the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (Figure 2.3). In reality, by 2018, inward FDI stocks were already 130% higher than the baseline estimation. A direct comparison cannot be made as other issues have not been held equal, but given the magnitude of the difference, it is plausible that reforms have more than paid off in terms of investment attraction.

By contrast, remaining restrictions may continue to imposing sizeable costs to the economy, not only in terms of forgone FDI and associated tax revenues, but also through economy-wide impacts on productivity growth. As mentioned above, services have proved to be a significant channel for value added generation in manufacturing industries (OECD, 2020a, 2018). The increased fragmentation of production chains across regions and globally exacerbates the role played by network industries and complementary business services in supporting manufacturing operations. Previous OECD (2018a) work demonstrated that the benefits of services liberalisation in ASEAN is greater for: i) manufacturing firms in machinery and transport equipment industries which rely extensively on services; ii) for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as compared to large firms; iii) domestic firms as opposed to foreign-owned firms; and iv) firms that do not export compared to exporters.

Market access reforms increase competitive pressures in services sectors and, consequently, productivity. In turn, this allows downstream manufacturers to benefit from higher quality services inputs or lower services input costs. As Myanmar aims to attract further investments into manufacturing, it may want to consider accelerating service sector reforms that contribute to fostering a level playing field for all investors.

A fair, transparent, clear and predictable regulatory framework for investment is a critical determinant of investment decisions and their contribution to development. Uncertainty about the enforceability of lawful rights and obligations raises the cost of capital, thereby weakening firms’ competitiveness and reducing investment. Moreover, ambiguities in the legal system can also foster corruption: investors may be more likely to seek to protect or advance their interests through bribery, and government actors may seek undue benefits.

The ability to make and enforce contracts and resolve disputes efficiently is, therefore, fundamental if markets are to function properly. Good enforcement procedures enhance predictability in commercial relationships by assuring investors that their contractual rights will be upheld promptly by local courts. When procedures for enforcing contracts are overly bureaucratic and cumbersome or when contract disputes cannot be resolved in a timely and cost effective manner, companies may restrict their activities. Traders may depend more heavily on personal and family connections; banks may reduce the amount of lending because of doubts about their ability to collect on debts or obtain control of property pledged as collateral to secure loans; and transactions may tend to be conducted on a cash-only basis. This limits the funding available for business expansion and slows down trade, investment, economic growth and development.

Investor protection under the new Myanmar Investment Law

The new Myanmar Investment Law (MIL) (2016) and the accompanying Myanmar Investment Rules (MIR) (2017) strengthened the investor protection regime afforded to foreign and domestic investors alike. These developments represent important strides towards reassuring investors that Myanmar is a secure investment destination in line with the government’s seven-point investment policy issued in December 2016 (DICA, 2016).2

The government’s guarantee of freedom from unlawful expropriation under Chapter 14 of the MIL marks a significant improvement from the previous regime (which is described in detail in the first OECD Investment Policy Review). It brings this guarantee in line with similar provisions found in other regional investment laws and Myanmar’s bilateral investment treaties (discussed separately below).

Article 52 of the MIL guarantees that the government will not nationalise investments covered by the Law, either directly or indirectly, except in certain enumerated circumstances and against fair compensation. Article 53 provides that compensation should reflect the “market value” of the expropriated investment subject to a consideration of several other factors including “the public interest”, “the interests of the private investor”, “the present and past conditions of investment”, “the reason for expropriation” and “the profits acquired by the investor during the term of investment”. These qualifications are unusual and could conceivably conflict with Myanmar’s obligations under its investment treaties (discussed separately below). Article 54 preserves the government’s policy space to regulate in the public interest in a manner similar to Annex 2 of the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (ACIA) by clarifying that non-discriminatory regulatory measures will not amount to indirect expropriation.

Aside from the guarantee against expropriation, three other investor protections in the MIL have either been introduced for the first time or improved substantially when compared to the previous regime.

A general principle of non-discriminatory treatment is codified in the new Law. Article 47 clarifies that foreign investors can now expect to be treated in a non-discriminatory manner as compared to Myanmar nationals (national treatment) and nationals of any other third country (most-favoured nation treatment). Neither of these guarantees featured in the previous regime.

A new guarantee of “fair and equitable treatment” (FET) in Article 48 is defined to cover two types of treatment – the right to obtain information on measures or decisions that impact a given investor or investment and the right to due process and appeal in respect of government measures, including any changes to terms of investment licences or permits granted by the government. This newly-introduced guarantee therefore appears to be more circumscribed and limited than the FET provisions in almost all of Myanmar’s investment treaties and the way in which arbitral tribunals ISDS cases have interpreted similar treaty provisions (discussed below).

The provisions in Chapter 15 of the MIL and Chapter 21 of the MIR guaranteeing free transfer of funds from investment activities in Myanmar are more sophisticated than under the previous regime. They set out with greater precision the categories of financial rights covered by the guarantee and introducing special rules during balance-of-payments and other financial crises that afford greater flexibility to the government in those circumstances.

Alongside the new investor protections are a progressive set of investor obligations in Chapter 16 of the MIL and Chapter 20 of the MIR – the likes of which are scarce in investment treaties in the region and worldwide – which broadly require investors to abide by domestic laws, abide by the terms of licences and permits issued to them, respect labour rights enjoyed by their local employees and follow international best practices to avoid environmental damage (see Chapter 4 and 6). The MIR empower the Investment Commission with an enforcement and supervisory role for some of these obligations. The investor protections are also subject to a range of general and security-related exceptions in Chapters 21 and 22 of the MIL that preserve the government’s right to regulate on a range of issues in the public interest.

As with investment laws in many other ASEAN member states,3 the new Investment Law does not contain a unilateral, binding undertaking by the government to submit future investment disputes with investors to international arbitration. Chapter 19 introduces an investor grievance mechanism, which is discussed further below. Disputes between the government and investors under the new Law that cannot be resolved amicably though this process can be resolved in contractual dispute forums (such as arbitration under investment contracts or investment treaties) or, if no such agreement exists, by the competent court or arbitral tribunal in Myanmar (which is not identified in the new Law or the Rules). As with Myanmar’s new Arbitration Law, it remains to be seen how Myanmar’s courts and arbitral tribunals will apply the MIL and the MIR rules in future disputes.

Protection of intellectual property rights

Significant developments have also taken place towards modernising Myanmar’s regime for protecting and enforcing intellectual property (IP) rights. Until recently, Myanmar had no statutory regime for trademarks, patents or industrial designs while the Myanmar Copyright Act (1914) enacted more than a century ago in the pre-independence era was widely considered deficient compared to international standards.

In 2019, Myanmar’s parliament enacted four long-anticipated IP laws following parliamentary and presidential approvals – the Industrial Design Law, the Trademark Law, the Patent Law and the Copyright Law. The new laws are intended to harmonise Myanmar’s legal regime with international standards in these four areas and create a modern, comprehensive coverage for IP rights in Myanmar.

The new laws are not yet in force. According to their terms, they will only come into effect on a date specified in a future Presidential notification. This is expected to take place once the administrative infrastructure and implementing regulations have been established to support the new IP regime. The government is currently prioritising efforts to draft implementing rules for the Trademark Law with a view to the Law coming into force in February 2021. Rules to support the other three new laws should follow shortly thereafter with technical support from a range of experts and external stakeholders.

Importantly, the new laws seek to align with the minimum standards for IP protection and enforcement set out in the WTO Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement. Once in force, the new laws will introduce dedicated statutory rules on trademarks, patents and industrial designs for the first time in Myanmar’s history. The new Copyright Law will repeal the Myanmar Copyright Act (1914) and introduce a range of new improvements on the previous regime. The improvements include protections for foreign works, modern definitions for several categories of protected works, a registration process and new enforcement options against copyright infringement. Existing copyrighted works with unexpired terms under the Myanmar Copyright Act (1914) will automatically qualify for protection under the new Copyright Law.

The enactment of the four new IP laws is the latest step in an ongoing process to establish a functioning regime for the protection of IP rights in Myanmar. The next step is for the government to draft and introduce implementing regulations for these laws for consideration by parliament. The Ministry of Commerce has been designated as the core government ministry responsible for administering the new laws with four other ministries – the Ministry of Information, the Ministry of Planning, Finance and Industry, the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, and the Ministry of Education – having supervisory roles.

Dedicated IP courts and authorities to supervise the administration, registration and enforcement of IP rights also need to be established. In the meantime, it will not be possible for investors to apply for rights under the new laws. The Ministry of Commerce, with technical assistance from World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the ASEAN Secretariat, the Japan International Cooperation Agency and other external IP experts, is leading efforts to develop plans to create a national IP office before the upcoming 2020 general elections to perform the administrative and supervisory functions envisaged in the new laws. The Supreme Court of Myanmar is empowered expressly under the new laws to establish dedicated IP courts but this process will undoubtedly take time. It will involve raising awareness and capacity for judges to deal effectively with IP-related disputes.

Myanmar may wish to increase its engagement in international fora as part of its efforts to modernise its IP protection regime. Myanmar is a signatory to a number of multilateral and regional conventions relating to IP protection, including the TRIPS Agreement, the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Intellectual Property Cooperation and the Convention Establishing the WIPO. The enactment of the four new IP laws in 2019 is an important step towards achieving domestic implementation of these commitments but challenges remain, as described above. In respect of the TRIPS Agreement, Myanmar and other WTO members from least developed countries have been allowed additional time – until 2021 for most standards and until 2033 for standards affecting pharmaceutical products – by the WTO’s TRIPS Council to achieve domestic implementation of TRIPS obligations. These extensions may allow Myanmar to implement its new IP laws and bring its IP rights regime into line with the TRIPS Agreement.

However, Myanmar is not yet a member of any of the 26 WIPO-administered treaties containing the most important international commitments on intellectual property. For example, some stakeholders report that the visually-impaired community in Myanmar wishes for the government to accede to the Marrakesh Treaty for the benefit of those affected by a range of disabilities that interfere with the effective reading of printed material, which Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand have all signed and brought into force in 2019 or 2020.

As with the new laws enacted in 2019, however, the success of any legal instruments adopted by Myanmar to establish a robust IP rights regime depends on whether newly-established IP institutions and courts are able to enforce registered IP rights effectively in practice. Coordination between government ministries and agencies will be critical to ensure that the new laws and forthcoming implementing regulations are enforced in a meaningful way. It will also be important to raise awareness of the implications of the new laws for local Myanmar business owners, as well as for customs and police officials, including the need to apply for IP registration and the consequences of infringement.

Access to justice and the court system in Myanmar

The existing infrastructure for domestic adjudication of civil disputes continues to suffer from a number of significant problems. Some of these issues seem to persist since the first OECD Investment Policy Review (OECD, 2014). The level of trust in the judiciary system is still low: it remains widely perceived as corrupt, inefficient, under-resourced and subject to the influence of the executive. Reforming the judiciary has been repeatedly identified as one of the biggest challenges faced by Myanmar in its reform endeavours, and various indicators consistently point to weakness in the justice system.

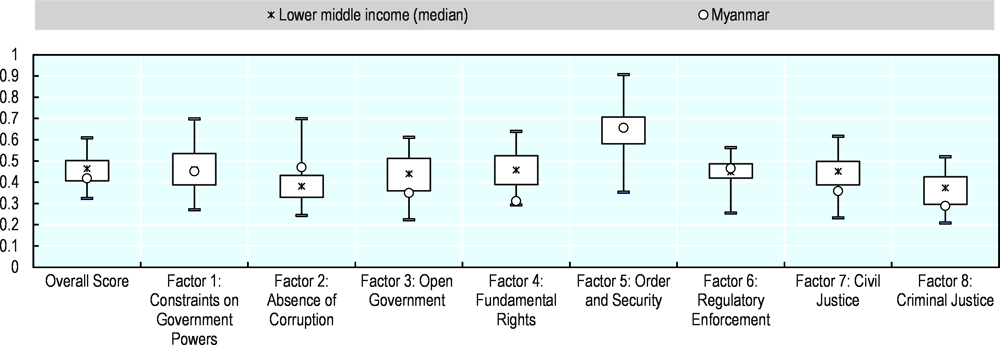

Myanmar ranks, for instance, 110th of 126 countries scored in the 2019 edition of the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index. This hard assessment is valid even if considering only other lower middle-income countries covered by the indicator. Myanmar’s performance is below the group median, sometimes significantly, in five out of eight sub-components of the WJP index (Figure 2.4). Only Cambodia ranks lower than Myanmar of the 15 countries scored from the East Asia & Pacific region. Myanmar ranks in the last five countries of 126 on both civil justice and human rights sub-components of the WJP Index. The World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 indicator also points to problems in the effectiveness of contract enforcement mechanisms in Myanmar, ranking the country 187th of 190 countries included in the indicator. While the average cost of enforcing contracts through the courts is at par with the average cost observed for East Asia and Pacific countries included in the Doing Business indicator, the time taken to resolve a dispute, counted from the moment the plaintiff decides to file the lawsuit in court until payment, is twice as high and the quality of the judicial processes is also estimated to be equally weak.4

While these results may partly reflect the legacy of the Military regime (see discussion below) and not fully take into account recent initiatives to improve the justice system, it remains nevertheless an area requiring particular attention by the authorities. Reforms are understandably difficult to implement in this area and may take a long time to show material results, but such dismal performance against peers reinforces the need for the government to strengthen existing efforts to improve the justice system.

Establishing a functionally independent judiciary and improving legal certainty under the Myanmar court system remain some of the biggest challenges faced by Myanmar in its democratic transition. Recent civil conflict in parts of Myanmar has attracted considerable international attention, notably with respect to potential human rights violations and the level of ‘state capture’ by the military who still maintains considerable economic and political power and enjoys full constitutional autonomy from any branch of the civilian government, including the judiciary (Reuters, 2018; UN Human Rights Council, 2018a and 2018b; International Commission of Jurists, 2018).

Since the first OECD Investment Policy Review, several initiatives have been pursued to improve the independence of the judiciary, the effectiveness of alternative dispute resolution and access to justice in Myanmar. The Supreme Court of Myanmar, with technical assistance from international partners, published the Judicial Strategic Plan 2015-2017 in November 2014 followed by the Judicial Strategic Plan 2018-2022 in January 2018. The Judicial Strategic Plans identify five core action areas: (i) protect public access to justice, (ii) promote public awareness, (iii) enhance judicial independence and accountability, (iv) maintain commitments to ensuring equality, fairness and integrity of the judiciary and (v) strengthen efficiency and timeliness of case processing. The 2015-2017 Plan earmarked three regional courts to pilot test strategic reform initiatives while the 2018-2022 Plan builds on the results and best practices developed in the pilot tests to establish a national case management programme that will be implemented in all courts in Myanmar by 2020.

Promoting greater access to justice, individual rights and adherence to the rule of law is also a key feature of the government’s Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan 2018-2030 published by the Ministry of Planning and Finance in August 2018. The MSDP identifies individual government agencies responsible for implementing the government’s goals of achieving judicial independence, transparent and consultative law-making processes and a stable rule of law at the community level and for conflict-affected areas. Planned actions include reforming the current legal aid system, increasing awareness of access to justice at the community level, developing a robust and independent legal profession, improving contract enforcement mechanisms and strengthening adherence to fair trial standards during criminal prosecutions.

Several access to justice programmes have also been established by international donors. The European Union and the British Council have partnered with civil society and non-government organisations to implement the “MyJustice” programme aimed at working with local communities to improve awareness about legal rights, local-level alternative dispute resolution options, legal aid opportunities and capacity-building for legal and court professionals. A survey published for the MyJustice programme in 2018 indicates that public perceptions regarding the functions and effectiveness of laws in Myanmar continue to be shaped by individual experiences under the Military regime and a significant number of Myanmar citizens do not have confidence that anyone can provide them with access to justice (MyJustice, 2018). This survey and other recent studies suggest that distrust of the official court system prevails, with many disputes not being brought to the official court system for resolution but rather to community-level justice institutions – primarily village tract administrators, village elders and religious leaders – that coexist with the official system (MyJustice, 2018 and 2016; Chan et al., 2017a and 2017b; Kyed et al., 2019). Other initiatives led by international donors have targeted capacity building for Myanmar criminal defence lawyers (Stevens, 2018). Initiatives include the Singapore-Myanmar Integrated Legal Exchange whereby Myanmar judges, court officials and law students benefit from various professional exchanges involving the Singaporean courts including study visits, collaborative seminars, symposiums and scholarship programs.

The new Arbitration Law

Myanmar’s new Arbitration Law came into force in January 2016. This is a significant development towards securing investor confidence in Myanmar’s domestic legal infrastructure in aid of commercial arbitration. The new Arbitration Law closely follows the text of the Model Law published by the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) in 1985 and amended in 2006, which is designed to assist states in reforming and modernising their laws on arbitral procedure.

One of the most important features of the new Arbitration Law is a codification of the principle that domestic courts shall not intervene in arbitrations except in certain limited circumstances. This should signal an end to decades of intensive court supervision of arbitrations in Myanmar under the previous pre-independence era laws.

Under the new Arbitration Law, parties may apply to the Myanmar courts during domestic arbitration proceedings in certain circumstances to appoint an arbitrator, compel the production of evidence, issue an injunction or decide a preliminary question of law.

The Myanmar courts are also vested with certain powers once an arbitral tribunal has issued an award in a domestic arbitration. Parties to domestic arbitrations under the Act can appeal to Myanmar courts on issues of law arising from an arbitral award. Myanmar courts also have powers to enforce domestic and foreign arbitral awards and determine applications to set aside arbitral awards. The limited grounds for Myanmar courts to refuse enforcement of a foreign arbitral award issued by a tribunal sitting outside of Myanmar are set out in the Arbitration Law in line with Myanmar’s accession to the 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards in July 2013. The Arbitration Law does not, however, appear to establish procedures for the Myanmar courts to set aside, recognise or enforce an international arbitral award issued by a Myanmar-seated arbitral tribunal (i.e. compared to a domestic arbitration between Myanmar entities seated in Myanmar). This is one issue that might be clarified in a future revision of the new Law.5

A curious feature of the Arbitration Law is that Myanmar courts may set aside a domestic arbitral award (Article 41(a)(vii)) or refuse to enforce a foreign arbitral award (Article 46(c)(ii)) if they find that to do so “would be contrary to the national interests of the State”. It is likely that this is intended to track the language of the well-known public policy exception in the New York Convention, but some ambiguity may arise with the official English translation of the Law, which adopts the formulation of “national interests”. This issue might be helpfully clarified in a future revision of the Law, its implementing regulations or a practice note issued by the Myanmar courts.

The enactment of the Arbitration Law is a laudable achievement but challenges remain for the implementation phase. Aside from drafting subsidiary legislation to accompany the new Law, as envisaged under the Supreme Court’s Judicial Strategic Plan 2018-2022, foremost of these challenges is the development of a truly independent judiciary (as discussed above) and building capacity within the regional courts empowered under the new Law to deal effectively with applications made under the new Law.

DICA reports that internal training on the Arbitration Law is being conducted for judges and court officials (DICA, 2016b), but as of August 2019, no applications have been filed under the new Arbitration Law to set aside, recognise or enforce domestic or foreign arbitral awards.6 It therefore remains to be seen how the judiciary will apply the new Law in practice. The Supreme Court, together with external technical experts, may wish to renew efforts to establish a dedicated commercial court staffed by judges that specialise in handling cases arising from commercial contracts and arbitration in a separate court list to other cases.

Another challenge lies in fostering a new generation of qualified lawyers and legal services firms to act as counsel in arbitrations and arbitration-related litigation in Myanmar. It is hoped that the newly-formed Myanmar Arbitration Centre (MAC) may be able to contribute to capacity building efforts and raising awareness for alternative dispute resolution (San Pé, 2016 and 2019). The Myanmar Arbitration Centre was launched in August 2019 following several years of preparatory work by a steering committee within Myanmar’s Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI) together with experts from regional international arbitration centres. As of August 2019, some uncertainties exist regarding the new MAC and its potential attractiveness to foreign investors in particular. These include the individuals that comprise its roster of arbitrators, whether parties may nominate arbitrators that do not appear on MAC’s roster of arbitrators and whether disputes governed by laws other than Myanmar law will be accepted.

Investment treaties

Myanmar is a party to 14 investment treaties (also referred to as international investment agreements or IIAs) that are in force today. Seven of these treaties are bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and seven of them are multilateral investment agreements in the context of Myanmar’s membership of ASEAN. Investment treaties entered into between two or more states typically protect certain investments made by nationals of a contracting state in the territory of another contracting state. Protections afforded under investment treaties generally arise in addition to and independently from domestic law protections. Treaty-based protections generally only cover investors defined as foreign. Increasingly, investment treaties also address market access for foreign investment.

Although Myanmar has signed eleven bilateral investment treaties (BITs),7 only seven of these treaties have entered into force, namely with China (2001), India (2008), Israel (2014), Japan (2013), Korea (2014), Philippines (1998) and Thailand (2008). Four other BITs –with Viet Nam (2000), Lao PDR (2003), Kuwait (2008) and Singapore (2019) – have been signed but not ratified and are therefore not in force yet. The Myanmar authorities have noted, however, that the Singapore BIT (2019) is expected to be ratified and come into force in 2020.

Myanmar is also party to seven investment agreements through its membership of ASEAN: the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (2009) (ACIA), in force for Myanmar since February 2012, as well as six agreements between ASEAN member states and third countries (ASEAN+ agreements) that contain investor protections in force between Myanmar and Japan (2008), Australia/New Zealand (2009), Korea (2009), China (2009), India (2014) and Hong Kong, China (2017).

Developments since the first OECD Investment Policy Review

In the six years since the first OECD Investment Policy Review (OECD, 2014) was published, Myanmar signed two agreements containing binding investor protections in the context of ASEAN, both of which are now in force, namely the India-ASEAN Investment Agreement (November 2014) and the ASEAN-Hong Kong, China Investment Agreement (November 2017). Myanmar has signed one new BIT in this period: the Myanmar-Singapore BIT (2019).

An ASEAN+ trade agreement concluded in 2008 with Japan did not originally contain investment protections or ISDS but an amending protocol signed in March 2019 adds these elements. The amending protocol came into force on 1 August 2020 for Japan, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam.

One BIT has also been terminated during this period. India notified Myanmar in March 2019 of its intention to terminate the BIT. India reports that the termination took effect on 21 March 2020.8 The provisions of the treaty will remain effective for fifteen years from the date of its termination (i.e. until 21 March 2035) in respect of investments made or acquired before the date of termination (Article 16(2)).

Myanmar has also been negotiating or considering some new investment-related agreements. In early 2019, together with ASEAN member states, it concluded negotiations for the First Protocol to Amend the ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, which added an investment and a trade in services chapters to the agreement. Myanmar has also been discussing in recent years with several new partners outside the Asia-Pacific region including the European Union,9 Canada10 and the Russian Federation regarding the possibility of future investment agreements.

Reconsidering Myanmar’s investment treaty policy

Myanmar’s investment treaties can be grouped in two broad categories: those that reflect the features often associated with older investment treaties concluded in great numbers in the 1990s and early 2000s (including Myanmar’s BITs with China, India, Israel, Kuwait, Laos PDR, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam) and those that reflect more recent treaty practice (including Myanmar’s BITs with Japan, Korea and Singapore, as well as ACIA and the ASEAN+ investment agreements).

Older investment treaties are generally characterised by a lack of specificity of the meaning of key provisions and extensive protections for covered investors. This scenario entails exposure, especially given that the majority of Myanmar’s BITs have vague standards of protection and very little regulation of ISDS. Two of the primary areas of Myanmar’s investment treaty policy for reconsideration are therefore its approach to substantive treaty standards, such as the FET standard, and ISDS mechanisms that would allow investors to bring claims against Myanmar in international arbitration proceedings. The next two subsections consider these two issues, followed by several other issues that Myanmar may wish to consider as part of a revaluation of its approach to investment treaties.

Fair and equitable treatment provisions

All of Myanmar’s investment agreements in force today contain provisions requiring Myanmar to treat covered investors fairly and equitably. The fair and equitable treatment (FET) standard is almost always at the centre of investment treaty policy debates and claims by investors under investment treaties. Most FET provisions were agreed before the rise of ISDS claims related to this treatment standard. Starting around 2000, broad theories for the interpretation of FET provisions by arbitral tribunals emerged as the number of ISDS cases increased.

Myanmar’s BITs with China, India, Israel, Philippines and Thailand do not provide specific guidance on the types of treatment that will be considered fair and equitable. Arbitral tribunals in ISDS cases under investment treaties have taken different approaches to interpreting similar “free-standing” FET provisions, which has created considerable uncertainty for investors and states alike. Governments have reacted to these developments in various ways, including by adopting more restrictive approaches to FET or excluding FET in recent treaties (see Box 2.2).

States are becoming more active in the ways in which they specify, address or exclude absolute FET-type obligations in their treaties and submissions in ISDS. Dissatisfaction with and uncertainties about FET and its scope have also led some governments to exclude it from their treaties or from the scope of ISDS. Some important recent approaches are outlined below.

The MST-FET approach. This approach involves the express limitation of FET to the minimum standard of treatment under customary international law (MST). This approach has been used in a growing number of recent treaties, especially in treaties involving states from the Americas and Asia (Gaukrodger, 2017).

In addition to using MST-FET, the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (2018) (CPTPP), contains a carve-out to address legitimate expectations, and requires the claimant to establish any asserted rule of MST-FET by demonstrating widespread state practice and opinio juris, which is difficult to do (Article 9.6 (3)-(5), fns 15 and 17, Annex 9A). This approach has since been replicated by other states (e.g., Australia-Indonesia CEPA (2019), Article 14.7). Myanmar’s BITs with Japan and Korea, as well as all of the ASEAN+ agreements barring with China, expressly link FET to the customary international law standard for the treatment of aliens.