Italy

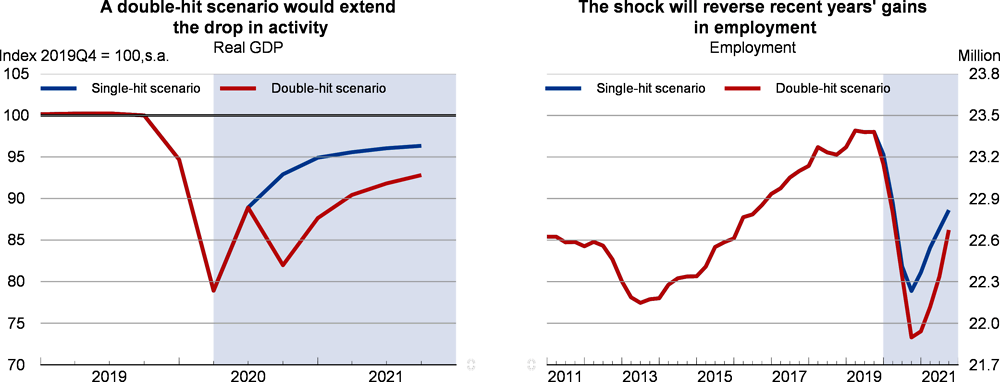

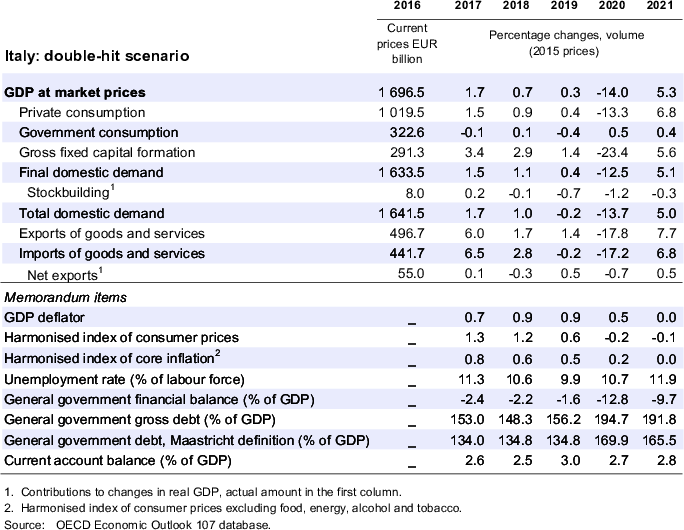

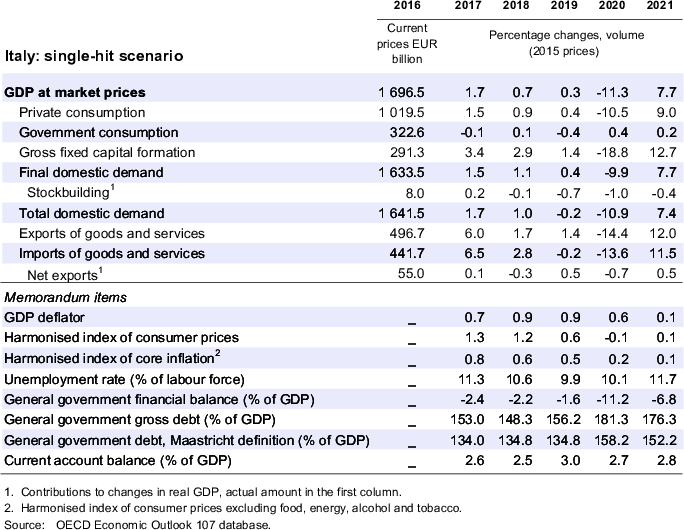

GDP is projected to fall by 14% in 2020 before recovering by 5.3% in 2021 if there is another virus outbreak later this year (the double-hit scenario). If further outbreaks are avoided (the single-hit scenario), GDP is projected to fall by 11.3% in 2020 and to recover by 7.7% in 2021. While Italy’s industrial production may restart quickly as confinement measures are lifted, tourism and many consumer-related services are projected to recover more gradually, weighing on demand. The COVID-19 outbreak and containment measures will leave output lower at the end of 2021 in both scenarios than at the start of the crisis and will reverse the gains in employment of recent years.

The government is supporting workers’ incomes and demand through transfers and short-time work schemes, and boosting firms’ liquidity by guaranteeing loans, deferring tax payments and offering tax credits. This is necessary to cushion the impact of the crisis, but, along with the fall in GDP, it implies a sharp increase in public debt ratios from already high levels, underlining the importance of placing the economy on a path of sustained growth. For sectors suffering large losses in demand, such as tourism, policy will need to help firms and workers to upgrade their operations and skills and to innovate.

COVID-19 cases grew quickly but were mostly in the northern regions

The COVID-19 pandemic started in northern Italy earlier than in most other OECD countries. Daily new infections peaked on 21 March, with most infections and deaths occurring in the northern regions of Lombardy, Piedmont and Emilia-Romagna. At the height of the outbreak in early April, a large number of patients were in hospitals, including over four thousand in intensive care, temporarily overwhelming the otherwise effective health system in the most affected regions. Italy’s health system is relatively well-resourced and ensures egalitarian access to care. It has doubled the number of intensive care beds since the start of the health crisis.

Italy responded quickly to the outbreak. It suspended direct flights from China from 27 January and declared a state of emergency on 31 January. The day after the initial clusters were identified, the authorities closed access and limited movements in the affected towns. As infections grew, the government imposed broader movement restrictions, banned events, closed schools and universities and non-essential service businesses – first across much of northern Italy and then nation-wide. At the end of April, Italy started to relax restrictions gradually. Construction and industries were allowed to restart production and movement restrictions were loosened, while distancing and sanitary protocols continued. Restaurants, bars and other services and facilities progressively reopened through May, at varying rates across regions depending on their epidemiological situation, and at the start of June Italy lifted restrictions on visitors from other European countries.

Confinement measures temporarily halted much of industry and restricted tourism

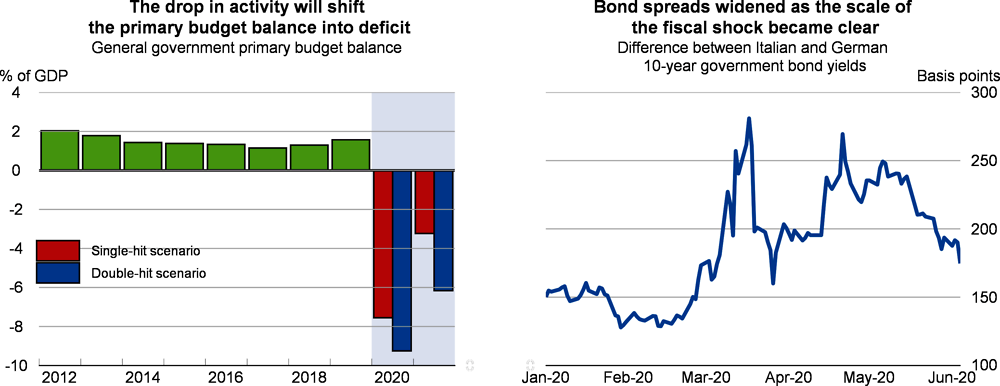

GDP fell by 5.3% in the first quarter of 2020, reflecting the effects of the increasing restrictions on consumer demand, investment and exports during March. The strictest confinement measures from late March to late April halted activity in about half of all businesses, which generate 53% of industrial value-added and 64% of Italy’s exports. Despite the enhancement of short-time work schemes and the suspension (until mid-August) of businesses’ ability to dismiss workers for economic reasons, employment fell by 1.2% between March and April 2020. Financial asset prices fell sharply in late February and early March as the extent of the crisis became clear. The Milan stock market index fell 30% below its mid-February peak, with bank shares plunging 45%, and government bond spreads widened.

Policy packages are supporting incomes, liquidity and access to finance

The government has announced three response packages with a total budget impact of EUR 75 billion (4.2% of 2019 GDP). The packages expand the health and civil response system’s capacity by funding 20 thousand additional workers and providing EUR 6.4 billion in extra funding. To support businesses’ liquidity, they defer and cut some tax rates, defer tax and contribution payments to later in 2020, guarantee up to EUR 530 billion in borrowing by businesses, and provide targeted tax credits such as for rental costs. These measures complement those of the ECB to reduce funding costs and ensure banks’ access to liquidity. The packages support incomes and employment by extending short-time work schemes, providing allowances to heavily impacted categories of self-employed workers, a last-resort safety net, and support for childcare, and by financing municipalities’ emergency support for the most vulnerable households. The government is preparing an additional package to help the recovery in public and private investment, including by simplifying administrative processes.

Industry can recover quickly but an extended outbreak will prolong losses for services

Industrial, construction and some service production restarted quickly as restrictions were lifted from late April. However, continued movement restrictions and sanitary measures, together with weak confidence and demand for exports are likely to slow the recovery in a single-hit scenario. In the double-hit scenario, the renewed containment measures are projected to lead to a further drop in exports and consumption, leading to prolonged weakness in investment. While restrictions on international travel are assumed to be lifted progressively from early June, the 2020 summer tourist season is likely to be very weak, despite efforts to support domestic tourism; this will be prolonged through 2021 in the double-hit scenario. Employment is slated to fall as short-term contracts are not renewed and once the government’s prohibition on dismissals expires in mid-August. In the single-hit scenario, the fall in jobs would be limited as the prospects of a recovery lead firms to retain many staff. Widespread dismissals are projected in the double-hit case. Prices are likely to be flat as the spare capacity in the economy offsets the disruption from the sanitary measures and movement restrictions. The recovery, combined with the government’s support measures and loan guarantees, may avoid widespread insolvencies among Italy’s many small enterprises. In the double-hit scenario, pressures on firms and households’ balance sheets and insolvencies will increase, slowing the recovery. Following the smaller-than-projected budget deficit of 1.6% of GDP in 2019, the deficit is projected to widen in 2020 to 11.2% of GDP in the single-hit scenario, before narrowing in 2021 as activity and revenues recover. Fiscal support and the budget deficit are projected to be greater in the double-hit scenario due to additional support measures and continued low revenues. Government debt ratios are projected to increase in 2020 to reach 158% of GDP in the single-hit scenario and to 170% of GDP in the double-hit scenario (Maastricht definition), before declining in 2021 as nominal GDP recovers.

Beyond the short-term risks linked to the pandemic crisis, the main risk relates to the strength and sustainability of the recovery. Italy’s tourism sector is especially vulnerable to the prolonged crisis of the double-hit scenario, as tourism risks being weaker into the medium term and small enterprises dominate the sector – 52 thousand in accommodation alone. Manufacturers may become more exposed if the downturn lengthens, as many firms specialise in high value-added and higher margin consumer and capital goods that may be more sensitive to lower global incomes and equipment investment. Italy’s firms and banks entered this crisis in better health than over the past decade, but the crisis heightens remaining financial fragilities, such as banks’ exposure to government bond prices. While the government’s extensive guarantees limit the risk of insolvencies and non-performing loans in the single-hit scenario, these risks are more significant in the double-hit scenario and they would add to the public sector’s liabilities. Ending the fiscal support prematurely would risk extending the bankruptcies and lost output caused by the crisis, especially in a double-hit scenario. Broadening fiscal support to ineffective measures, or for longer than necessary, would further raise the public debt burden and the challenge it poses to the economy without sustainably supporting activity.

Enabling investment and new opportunities would help restart the economy

The COVD-19 crisis is a setback in efforts to achieve stronger and more inclusive growth. The emergency measures to deal with the economic fallout of the crisis are justified, and these should further complement and renew efforts towards pursuing an ambitious structural reform programme. Continuing to extend support in sectors where demand is likely to return quickly can avoid unemployment and accelerate the recovery. Businesses and workers likely to face extended weak demand would benefit from support to upgrade, invest and innovate, and to shift to sectors with better prospects, through strengthening active labour market policies, particularly retraining schemes, and by facilitating investment. Streamlining and improving access to income support programmes, such as the Citizen’s Income, would prevent large increases in poverty and support demand in the recovery. If non-performing loans start rising, the government should stand ready to reinforce the bank asset support programme (GACS). Implementing the new bankruptcy law would help by ensuring that viable companies are restructured rather than liquidated. Pursuing the government’s plans to develop a multi-year programme to reduce administrative complexity, improve the legal system’s effectiveness and reduce investment and employment costs would support new businesses, productivity and jobs. Supporting the renewal of the ageing infrastructure and the transition to lower carbon activities would sustain the recovery and improve well-being. Accelerating the adoption of digital technologies, as demonstrated by the rapid move during the crisis to ‘smart working’ and online services, would raise competitiveness.