3. Active labour market policies and COVID-19: (Re-)connecting people with jobs

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) will be vital in shaping the labour market recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. Connecting people to jobs through effective training, assisting companies to retain and recruit staff, and providing comprehensive support to people with major employment obstacles, will help to ensure an equitable and efficient emergence from the crisis, avoiding labour market detachment of more vulnerable individuals. Many countries reacted swiftly in increasing funding for their public employment services (PES), training programmes, hiring subsidies and other measures to increase labour demand. PES have hired additional staff and expanded remote and digital accessibility to their services to ensure service continuity. This chapter draws on a cross-country survey of policy responses to the crisis to highlight areas of good practice and institutional features that facilitated the development of contingency plans and adjustment to the new environment.

Despite the significant progress in the vaccination campaign in many OECD countries and the gradual re-opening of their economies, in April 2021 there were still 7 million more people unemployed than before the onset of the pandemic and many more discouraged jobseekers and people on reduced hours of work. In the still uncertain recovery, active labour market policies (ALMPs) play an important role as they help displaced workers find jobs more quickly and facilitate the matching of jobseekers with emerging job opportunities. At the same time, ALMPs are needed to support the labour market integration of groups with major employment obstacles to build a more inclusive labour market in the recovery. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, governments across the OECD are developing or putting into place medium- to long-term strategies to boost the jobs recovery and be better prepared for future shocks. These strategies include redesigning and scaling up ALMPs and increasing funding for their public employment services (PES). This chapter reviews how countries reshaped their PES and ALMPs to cope with the pandemic and prepare for the recovery. It presents new analysis on the institutional features that enabled a quick and effective response to the crisis. It draws on the responses of 45 countries and regions to an OECD/European Commission questionnaire on “Active labour market policy measures to mitigate the rise in (long-term) unemployment”, conducted at the end of 2020. The chapter highlights good country practices and identifies key challenges that will need to be addressed in the future.

PES together with private employment services (PrES) have been playing a key role in supporting jobseekers, employers and workers since the start of the pandemic:

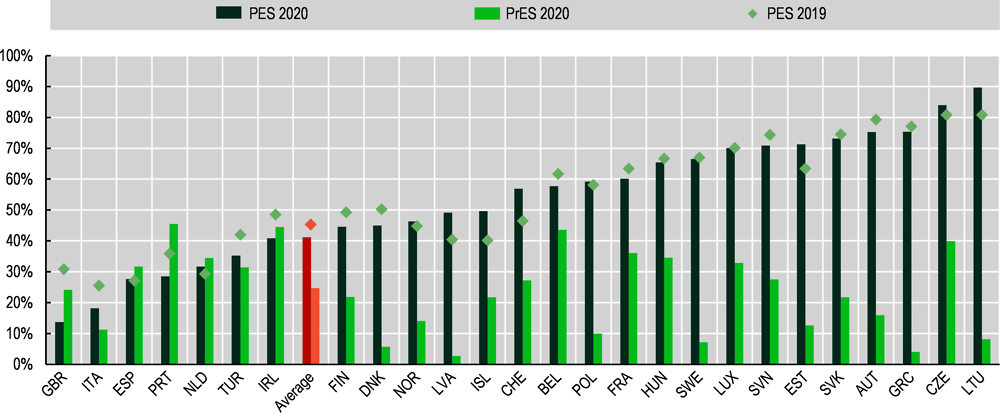

Despite social distancing restrictions, difficulties in service provision and limited job vacancies, 41% of all unemployed people contacted the PES to find work in 2020 in Europe (EU countries plus Iceland, Norway, Switzerland) and Turkey, just 4 percentage points below the 2019 figure. This underlines the important role of the PES and PrES in providing good quality services to a growing number of clients.

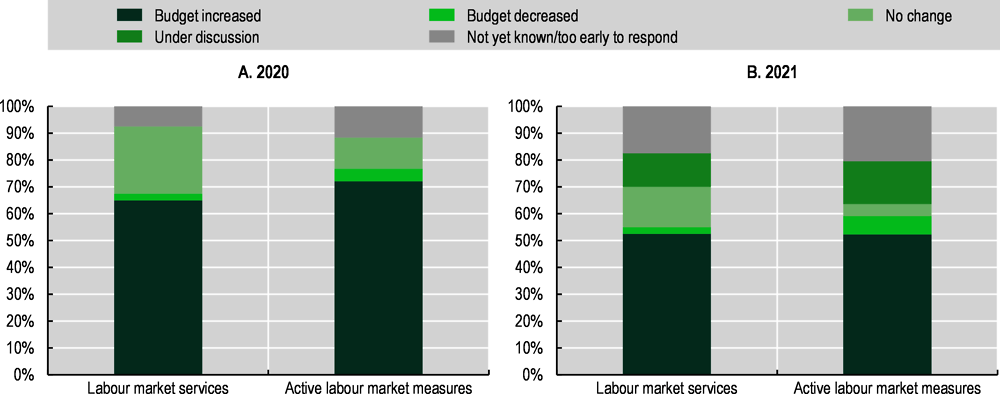

Around two-thirds (65%) of countries increased their budget for public employment services and administration over the course of 2020 and just over half (53%) of countries plan increases in 2021 beyond the 2020 level. The reallocation and training of staff have also been used to increase PES capacity. Almost 90% of countries responding to this question indicated that changes in PES operating models (principally adjustments in service delivery processes, the expansion of remote channels and reallocations of staff) represented the core of their short-term employment policy response to the COVID-19 crisis. Some countries also increased capacity by contracting out employment services to complement public provision and address peaks in demand.

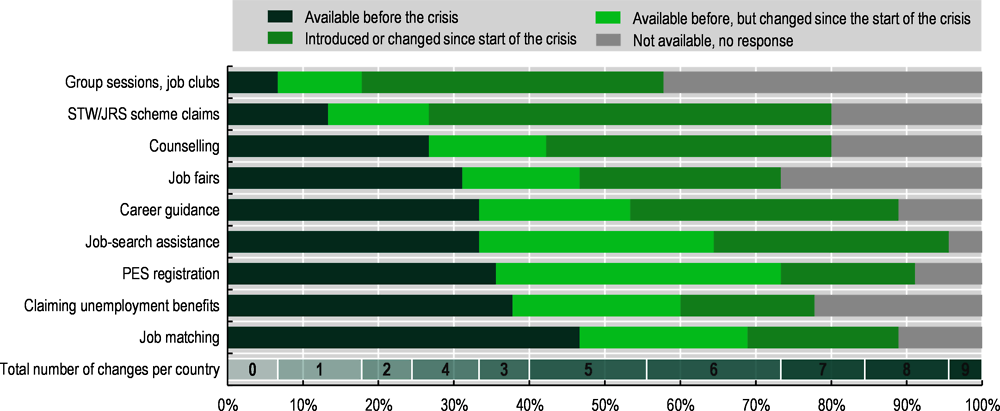

During the crisis, there was a widespread need for PES to rapidly scale up the use of digital and remote services to continue providing support to clients. Around 80% of PES offered remote access, compared with 50% before the pandemic. Of the PES that offered remote access to services prior to the pandemic, around 40% subsequently expanded this offering to facilitate delivery during the crisis (e.g. by streamlining application processes or opening up more digital channels).

The scale of the expansion of remote and digital access in less than one year almost exceeded the total volume of digital services built up prior to the pandemic. Going forward, it is vital that each country’s PES continues to develop its technological capacity to enable customers to engage with services digitally and fully utilise the tools and information at their disposal online.

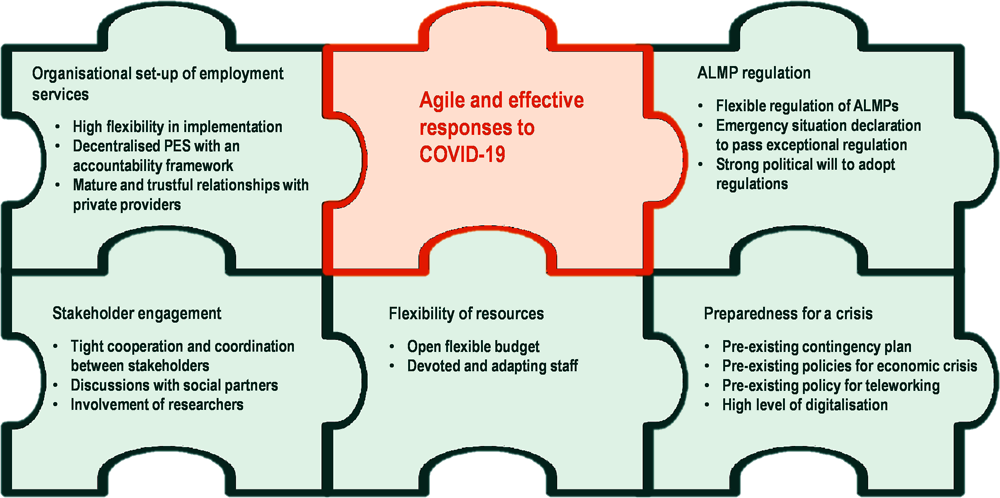

Certain features of the institutional and regulatory set-up of ALMP provision have influenced each country’s ability to adjust to the new environment and develop contingency plans and new strategies:

More than half of countries responding to the OECD/European Commission questionnaire highlighted co-operation and co-ordination between stakeholders and policy domains (e.g. health, employment and social policies) among the main factors facilitating their COVID-19 responses. Moreover, all countries have involved almost all key stakeholders (the PES, the ministry responsible for labour market policies, the social partners, sub-national levels of government and private providers) in their ALMP systems when developing their strategies.

Close to a third of countries stated that flexibility in ALMP implementation due to their organisational set-up has been crucial for their agile response to the crisis. Some favourable features of the organisational set-up are highlighted by two-thirds of countries with a PES set up as an autonomous public body with tripartite management.

Countries with more flexible ALMP regulations (e.g. where the legislation passed by parliament only defines the main principles of ALMP provision, with the details of design and delivery set by lower-level regulations) were able to redesign their policies faster. Meanwhile, countries where the details of ALMP design require the approval of higher-level institutions, or where there is a more complex regulatory system, experienced delays in adjusting their ALMPs.

Recognising the important role played by ALMPs in mitigating the impact of the crisis, seven in ten OECD and EU countries reported an increase in funding for active labour market measures in 2020 and half of the countries are planning increases in 2021. While too early to assess the adequacy of public spending on ALMPs in 2020 and 2021, past evidence suggests that there is a clear risk of countries investing too little. Moreover, the effectiveness of public spending will depend on a successful implementation of the measures that were – or will be – introduced or adapted to support the recovery. Additional investments may be necessary in a number of areas:

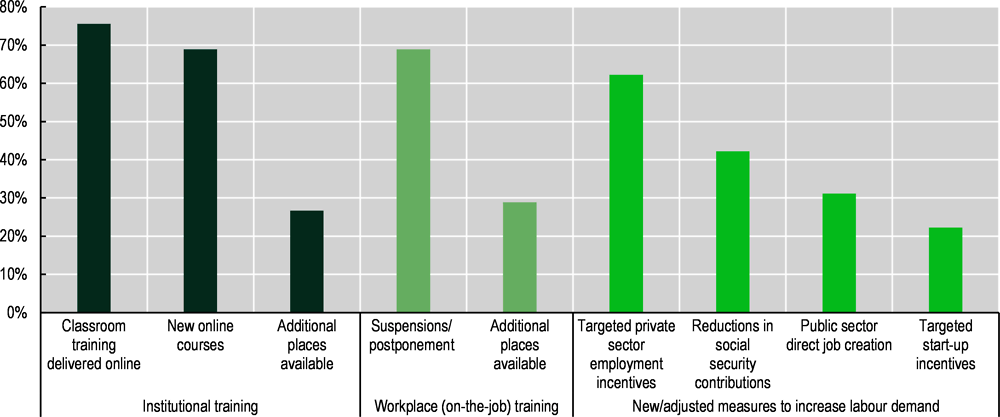

Investing in up-skilling and re-skilling of unemployed and displaced workers is important to support job transition in the recovery and respond to changes in the demand for skills brought by automation, digitalisation and structural changes. Training programmes have been found to be particularly effective during past downturns as lock-in effects (enrolment in training programmes preventing an early return to work) tend to be smaller. Training has therefore been expanded during the pandemic to support the reallocation of workers and to upskill those at risk of displacement, with countries making additional training places available and moving classroom-based training courses online. More than ever before, the current crisis has emphasised the importance of cultivating the skills needed to access various digital tools, including for job search and online training.

Measures to foster job creation and increase demand for labour have been introduced or expanded in many countries. Almost two-thirds of OECD and EU countries have scaled up their employment incentives and 42% of countries lowered social security contributions for some or all employers. This was important to preserve employment that had been impacted by sudden economic shutdowns imposed by COVID-19 and to prevent detachment of individuals from the labour market. The targeting of employment incentives on groups in need can increase their effectiveness and avoid money being wasted on subsidies for the hiring or retention of workers who would have been hired or retained anyway. Many countries have therefore targeted their new measures on young jobseekers, the long-term unemployed, people with disabilities, the older unemployed and other disadvantaged groups. Other countries expanded public sector direct job creation programmes and start-up incentives. Further changes in the mix and sequencing of ALMPs might be needed as countries enter the recovery period.

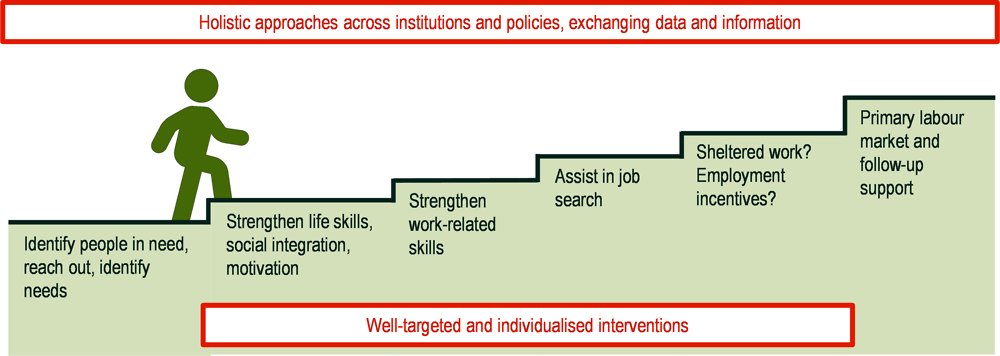

This crisis risks leaving deep scars on vulnerable groups marginally attached to the labour market facing major or multiple employment obstacles. Barriers to (re)enter the labour market include scarce work experience faced by many young people, care obligations particularly amongst women with young children, low skills or health limitations. Not all these groups show up on the radar of PES, which is why it is important to identify the groups at risk and their needs, develop effective outreach strategies, and provide integrated, comprehensive and well-targeted support. This in turn requires a good exchange of information and co-operation between the relevant institutions responsible for the provision of employment, health, education and social services, as well as income support.

Furthermore, evaluations of the new policies and programmes introduced in response to the COVID-19 crisis will be required, to identify effective ones and those that are less effective and need to be adapted or terminated. These efforts should be best embedded in a broader framework of evidence-based policy making that would enable countries to conduct regular and timely evaluations of their policies.

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) perform an important function in making labour markets more resilient, helping displaced workers to get back into work quickly and enabling them to seize emerging job opportunities. The deep shock to labour markets everywhere brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of this role but also the strain that has been placed on traditional ways of providing employment assistance to growing numbers of jobseekers in a time of social distancing and restrictions on mobility.

Against this background, this chapter illustrates the part that public employment services (PES),1 private employment services (PrES)2 and ALMPs have played, and continue to play, during the COVID-19 pandemic in supporting jobseekers, employers and workers based on new information on countries’ policy responses (see Box 3.1).

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. First, it shows the extent to which unemployed people remained active during the crisis and contacted the PES to find work (Section 3.1). Second, it presents a new dashboard of the institutional set-up of ALMP provision in OECD and EU countries, highlighting features that have enabled a quick and effective response to the current crisis and detailing the key elements of countries’ strategies for moving from crisis management to medium- and long-term strategies (Section 3.2). Third, it shows how countries adjusted their funding for ALMPs over the course of 2020 and 2021 and how investments in technology can increase the effectiveness and efficiency of these policies (Section 3.3). Fourth, the chapter provides an overview of the areas in which countries have already adjusted and extended their ALMPs. It pays particular attention to vulnerable groups, who are facing major labour market integration obstacles and are at risk of being left behind in the economic crisis, and outlines the support needed by these groups to enable them to improve their labour market outcomes and access good jobs (Section 3.4). The chapter concludes with some remarks on the importance of continuous evaluation of policy measures to identify those that are less effective and need to be modified or terminated (Section 3.5).

The analysis presented in this chapter draws on a questionnaire on “Active labour market policy measures to mitigate the rise in (long-term) unemployment” sent by the OECD Secretariat in collaboration with the European Commission (EC) to all OECD and European Union (EU) member countries in September 2020, with responses received during October and November 2020 from 45 countries and regions. For Belgium, four sub-national responses were received and these are counted separately in some of the statistics of the chapter1, although the chapter generally uses the term countries in all cases.

In order to obtain a comprehensive overview of the discretionary ALMP measures taken in response to the COVID-19 crisis, the questionnaire asked countries to provide information on policies and programmes in place in 2020 or planned over the course of 2021. Also included were questions on the institutional set-up of active labour market policy design and provision, as well as institutional settings that influence the responsiveness of ALMPs during times of crisis.

The chapter also benefited from information collected from PES across the European Union by the Secretariat of the European Network of Public Employment Services, on behalf of the EC on PES actions that have been implemented or will be introduced to cushion the effects of COVID-19. This information has been updated frequently since March 2020.

← 1. The four questionnaire responses from Belgium concern the three regions of Brussels, Flanders and Wallonia and the country’s German-speaking community.

This section uses data available from the European Labour Force Survey to examine changes in the number and composition of unemployed people who contact the PES to find employment. The number of unemployed people who contacted the PES to find work in Q2-Q4 2020 has risen in many countries but not in all. In 16 out of the 26 countries presented in Figure 3.1, the share of unemployed who contacted the PES to find work out of all unemployed has fallen in the second, third and fourth quarters of 2020 relative to the same period in 2019. This reflects the confinement measures that severely restricted mobility of job seekers as well as the operation of PES in many countries throughout 2020, and the fall in available vacancies. Nevertheless, large increases are observed in Switzerland, Latvia, Lithuania, Iceland and Estonia. In the latter, the increase may still reflect, at least partly, the effects of the Work Ability Reform, which increased the incentives for people with long-term health conditions or disabilities to register with the PES, offered them comprehensive services and promoted their labour market participation.

The drying up of job vacancies as a result of lockdowns and social distancing requirements also meant that it was neither feasible nor desirable to keep up mutual obligations requiring jobseekers to actively look for work while receiving benefits. As part of their initial response, one in seven countries suspended job-search requirements and six in ten countries changed them, sometimes following an initial suspension. Among countries that suspended or changed job-search requirements the vast majority had restored such requirements by the end of 2020. The pace was different across countries, with some restoring the requirements at the end of the first lockdown periods (e.g. France and Latvia), whereas other countries waited until the third (e.g. Australia, Estonia and Switzerland) or fourth quarter (e.g. Finland, Israel, Luxembourg) of 2020.

While enforcement of job-search requirements is important to uphold the active stance of an activation regime that seeks to encourage active job search and reduce benefit dependency, it needs to be matched by maintaining mutual support offered through the PES. Indeed, countries taking longer to fully restore job-search requirements first needed to make adjustments to their delivery channels expanding online services, e.g. through introducing or expanding remote channels to deliver job-search assistance, before restoring the pre-COVID-19 requirements. In-person services are often reserved for more vulnerable jobseekers (see Section 3.4.3) or only used for specific transactions (e.g. referral to ALMPs). Over a quarter of countries did not change their job-search requirements due to the COVID-19 imposed restrictions. Countries that kept their job-search requirements intact often already had online and other remote channels of job-search assistance available before the crisis (e.g. Chile, Japan, Norway; see also Figure 3.8).

Despite the drop in the number of vacancies and limited hiring taking place during the last three-quarters of 2020, unemployed people still relied on the support of PES in their job-search efforts. In total, in Europe and Turkey, 41% of unemployed people contacted the PES to find work in 2020, slightly below the share in 2019 (45%). In over 42% of the countries in Figure 3.1, this share was above 60% and reached 90% in Lithuania, 84% in the Czech Republic and 75% in Austria and Greece. In contrast, in the United Kingdom and Italy only 14% and 18% respectively of unemployed people contacted the PES to find work in 2020, which represents a further decline of 17 and 7 percentage points respectively relative to the same period in 2019. Private employment services also support the unemployed in their job search. Close to one-quarter of unemployed people contacted private employment services to find work in Europe in 2020.3

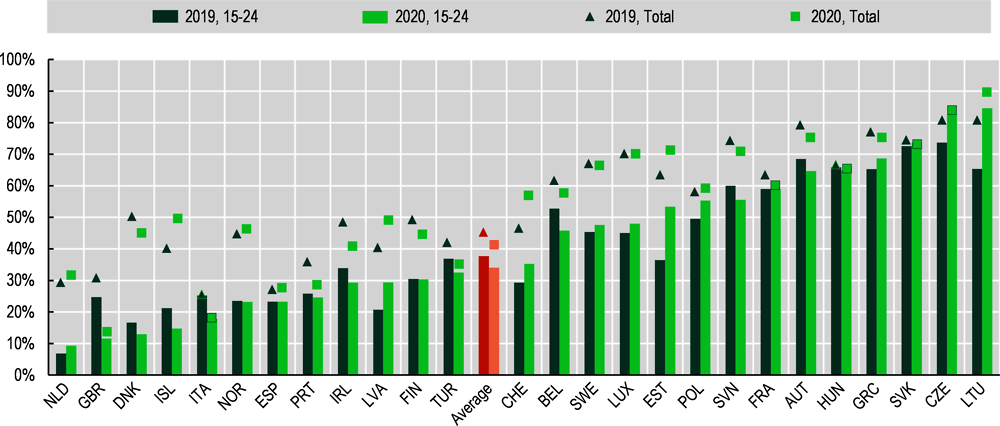

The groups that have been more heavily affected by the COVID-19 crisis and who were also the most vulnerable groups after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), tended to have less contacts with PES during the pandemic. Notably, young unemployed people use the PES much less than other age groups, and this gap has increased over time.4 In total, in Europe and Turkey, only 34% of the unemployed aged 15 to 24 years contacted the PES to find work in 2020, versus an average of 41% among all age groups (Figure 3.2). Moreover, this share also declined by 4 percentage points during the COVID-19 pandemic. PES outreach is even lower in some European countries: fewer than 15% of unemployed youth contacted the PES to find work in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Iceland. In addition, in the United Kingdom and Iceland, this share dropped by 13 and 6 percentage points respectively between 2019 and 2020. In contrast, unemployed youth in Estonia and Lithuania relied even more on the PES to find work during the pandemic, with the shares increasing from 36% and 65% in 2019 to 53% and 85% in 2020 respectively.

Some countries have managed to adjust to the new environment imposed by COVID-19 and develop contingency plans and new strategies quickly and smoothly, while others have struggled. This section first presents key features of the institutional set-ups of ALMP provision in OECD and EU countries and then identifies those features that enabled swift responses to the crisis. It also discusses the content of country responses as they have moved from crisis management to adjusting medium- and long-term strategies.

3.2.1. How the institutional set-ups of ALMP provision can support agile responses during times of crisis

The dashboard presented in this section provides a schematic framework to help identify key features of the ALMP systems that enable quick responses to changes in labour market conditions and efficient adjustments in the provision of ALMPs. The dashboard displays the institutional set-up of ALMP provision separately in three dimensions (see specific indicators in Annex Table 3.A.1 and complementary discussion in Lauringson and Luske (forthcoming[1])):

Organisational set-up of ALMP provision – the division of responsibilities for ALMPs, co-ordination and co-operation between the key stakeholders.

Regulatory set-up of ALMP provision – the key legislation relevant for ALMP design and implementation.5

Capacity of ALMP systems – the resources for employment services and ALMP measures.

Organisational set-up of ALMP systems varies across countries more in terms of policy implementation than policy design

The high-level responsibilities for labour market policies and thus for providing the general framework for ALMP provision lie in the relevant ministries, although more stakeholders are often involved in the policy design. In systems where the ministry responsible for labour market policies and PES are separate public bodies, generally both organisations are involved in designing strategies and accountability frameworks for ALMP provision, as well as ALMP interventions and their budgets (Annex Table 3.A.1). While a single body responsible for drafting changes in policy design might make the process quicker in an emergency situation, involving more stakeholders might ensure better implementation. Furthermore, the majority of ALMP systems (76% of countries responding to the OECD/EC questionnaire) have an official or quasi-official role for the social partners whether through advisory or supervisory bodies, and almost all other countries involve the social partners ad-hoc for consultations (except Israel and Mexico).6 These practices could potentially facilitate designing policies that meet the needs of both labour demand and supply.

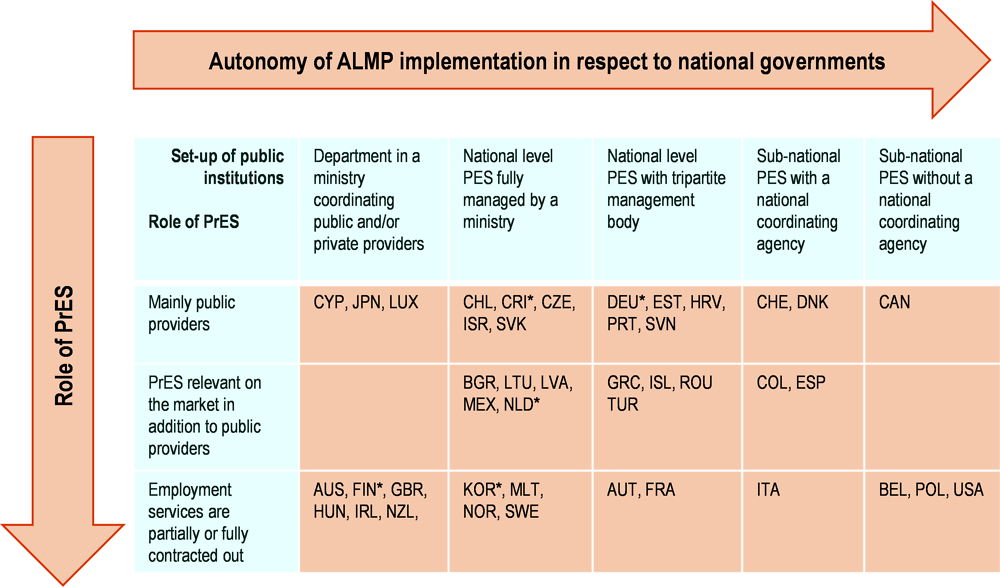

There are stark differences in the organisational set-up of ALMP implementation (Figure 3.3), particularly concerning the autonomy of organisations implementing ALMPs. This can heavily affect the agility of the system. On the one hand, greater autonomy of PES and involvement of PrES can facilitate fast changes in operating models, which is crucial in a health crisis when rules on the working environment change abruptly. On the other hand, for contracted-out employment services, it might be difficult to change the contractual terms as a result of sudden changes in needs. The continuation of service provision may then depend largely on willingness of PrES to co-operate. High levels of decentralisation of ALMP provision can lead to more responsiveness to local labour market needs (OECD, 2020[2]; 2014[3]), but require a well-designed national-level accountability framework to function successfully in the long term (Weishaupt, 2014[4])).

In addition to implementing ALMPs, many PES have additional tasks and responsibilities. For example, slightly more than half of the PES in the European Economic Area (EEA) are partially or fully responsible for unemployment benefit schemes (Peters, 2020[5]). Other responsibilities can include administering short-time working schemes, social assistance benefits, parental benefits, pre-retirement benefits or sickness and disability benefits, managing training centres and career services for schools, issuing work permits, licencing private employment services and beyond. A crisis in the labour market means that the PES in charge of benefit schemes are under particular pressure as the needs for both active and passive labour market policies increase. Yet, responsibilities for other services and measures might help PES provide more integrated and holistic support to the people. Furthermore, different services, measures and benefits facilitate PES outreach to vulnerable groups and motivate them to register (Konle-Seidl, 2020[6]).

Finer details of specific ALMPs are often set in few flexible regulations

High-level regulations of ALMP provision can limit the flexibility of the regulatory set-up. Generally, the higher the level of the institution that needs to adopt the regulation, the longer the process takes; also as these regulations often need to be approved first by lower-level bodies. For example, amending an act in a parliamentary process can take considerably longer than adopting a ministerial decree or amending a PES internal guideline. However, it might be important to fix the general framework for ALMP provision (the organisational set-up, objectives of ALMP provision) in higher-level regulations to make a top political body accountable for the system and ensure democratic processes.

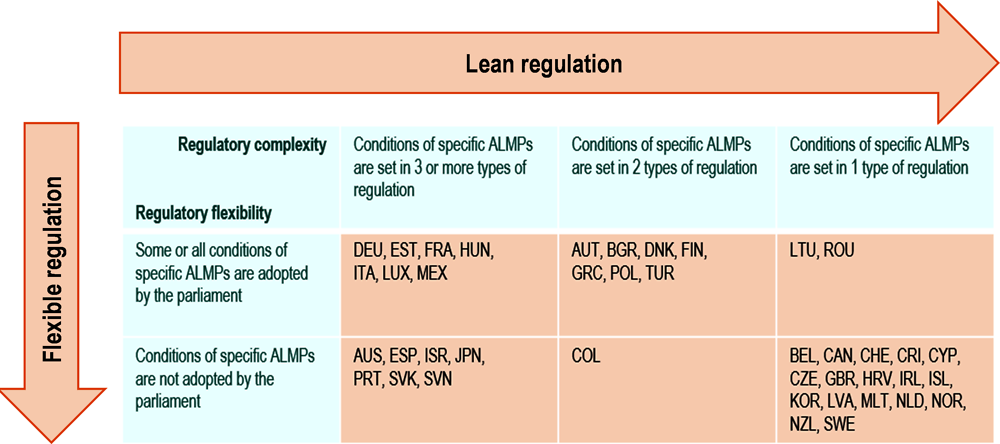

The agility of the regulatory set-up also depends on the complexity of the system. When ALMP design is set in several regulations, amending the design to meet the changing needs of the labour market can be a cumbersome process.

Figure 3.4 provides an overview of how agile the regulatory set-ups of ALMP provision across the OECD and EU countries potentially are. The complexity of regulation is indicated by the number of types of regulations that set the conditions of ALMPs (i.e. design of ALMP measures and services). Theoretically, this number could be up to eight (regulations adopted by the parliament, government, minister, ministry, PES supervisory body, PES executive management, regional or local authorities or other bodies). In practice, only eight countries use more than three types of regulations to set ALMP conditions, although the number of regulations can in practice be higher if several regulations on the same level are in force. The indicator for the flexibility of the ALMP regulation is defined in two groups – whether at least one regulation for ALMP conditions is an act passed by the parliament or not. More than half of the countries belong to the latter group and they could potentially change the ALMP design swiftly when labour market needs change.

Capacity of ALMP systems defined through public expenditures on employment services and ALMP measures

More resources available for ALMP systems before a labour market shock occurs can facilitate absorption of increased pressure on the system. In most OECD and EU countries, budgets for ALMPs are not automatically adjusted according to the labour market situation and amending budgets follows fixed procedures, including negotiations between stakeholders. Even in countries where ALMP budgets do have automatic corrections (Belgium (Flanders), Switzerland), actual implementation of the budget can take some time – e.g. hiring additional staff for employment services or contracting out additional training places. A system with lower caseloads for employment counsellors could more easily continue with effective job search counselling by making some adaptations (cutting time for counselling sessions, focusing on more vulnerable groups, cutting some parts of additional support services), while a system already working on its limits might not have any room for manoeuvre.

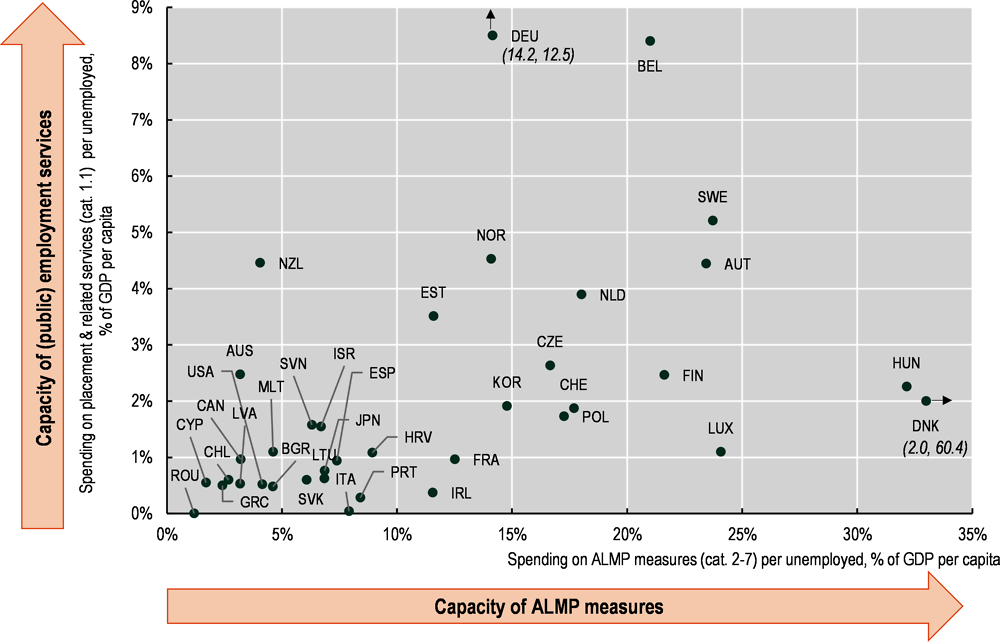

Figure 3.5 provides some indication of the capacity of ALMP systems before the COVID-19 pandemic. The figure displays on the horizontal axis the expenditures on ALMP measures (categories 2 to 7, i.e. training, employment incentives, supported employment and rehabilitation, direct jobs creation and start-up incentives) per unemployed as a share of GDP per capita in 2018. This indicates the capacity of the system to support jobseekers with intensive interventions and takes into account the level of unemployment in countries. The vertical axis displays the expenditures on placement and related services per unemployed as a share of GDP per capita – category 1.1 according to the OECD categorisation of labour market policies that aim to capture expenditures on employment services by public employment services and other publicly-financed bodies, but excluding expenditures on benefit administration (OECD, 2015[7]). The latter is an indication of staff levels and caseloads in the employment services. Furthermore, empirical evidence shows that these types of expenditures are generally most cost-effective as the relative cost is lower compared to other ALMPs (Brown and Koettl, 2015[8]; Card, Kluve and Weber, 2018[9]). An ALMP system was potentially able to absorb the first effects of COVID-19 better when neither of the indicators were at a low level.

Although the latest data for ALMP expenditures are from 2018, these likely present the situation relatively well also for the beginning of 2020, as the resources available for ALMPs do not change usually a lot from year to year when the economic situation is relatively stable. Nevertheless, the indicators might underestimate or overestimate the capacity of systems in countries where it is not possible to accurately differentiate between expenditures for administrating ALMPs, and benefits and other measures, or where digital tools are highly advanced and the need for staff is lower.7 Annex Table 3.A.1 provides an additional indicator for the capacity of the ALMP systems comparing ALMP expenditures (without administration costs of labour market policies and other activities, i.e. categories 1.1 and 2 to 7) to expenditures on passive labour market policies (categories 8 to 9, above all unemployment benefit schemes) to indicate how activation oriented different labour market policy systems are.

Institutional features that enable effective and agile responses to labour market shocks identified by countries in 2020

The most important features highlighted by countries to enable them to develop both their short- and long-term responses to COVID-19 were stakeholder engagement, organisational set-up of the ALMP system, regulatory set-up of the ALMP system, resources for ALMPs and preparedness for a crisis that imposed remote working arrangements (Figure 3.6).

Virtually all countries have involved all key stakeholders of their ALMP systems in developing their strategies on mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 crisis on the labour market, taking advantage of the wider set of expertise this offers. Countries that have a national level organisation for PES overwhelmingly involve them in strategy development, in addition to the ministry responsible for labour market policies. Other key partners in the development process have been employers’ associations and trade unions, sub-national levels of government and ALMP providers (such as organisations representing local private employment services and training providers). Strategy development has often involved other ministries and public sector institutions more closely than before to ensure co-ordinated responses to the crisis across policy fields. For example, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Australia dissolved the New Employment Services Reference Group to allow for the establishment of a new advisory group with a broader remit to support economic recovery, including experts across business, training, social welfare and the employment services industry.

Tight co-operation and co-ordination between the stakeholders in ALMP systems has been key to quick and well-designed responses to address the challenges in the labour market posed by the COVID-19 outbreak. More than half of the countries replying to the OECD/EC questionnaire highlight co-operation and co-ordination as one of the main factors facilitating their COVID-19 responses. Co-ordination and established governance models have become particularly critical in decentralised systems, where a high share of responsibilities for ALMPs lies in the regional or local level authorities (last two columns in Figure 3.3). For example, Italy has worked intensively on establishing the governance model and stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities after a major reform in the organisational set-up was launched in 2014-16, and which results have facilitated the country to co-ordinate responses to COVID-19 crisis. Co-operation and establishment of designated steering groups for crisis management have been important in systems where responsibilities to design and implement ALMPs are shared among several national level organisations, such as in cases where the PES is set up as an autonomous public body (countries in the middle column in Figure 3.3). For example, the ministry and PES in Slovenia have had almost daily contact since the start of the COVID-19 crisis, which is based on a long tradition of open communication between the two organisations and shared objectives.

Close to half of the countries that consider the co-operation of stakeholders as a particularly beneficial practice, highlight that engaging the social partners in the development of their short- and long-term responses has been of particularly high value. In addition, Austria, Belgium (Brussels), Finland and Norway have involved researchers in the development of their employment policy responses. In the Brussels region, View Brussels (the Brussels Employment and Training Observatory, whose main mission is to observe and analyse the regional labour market) has participated actively in the dedicated task force to re-design and implement employment policy in response to COVID-19, providing the task force with regional monitoring data. In Finland, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment and the Ministry of Finance appointed a working group swiftly when COVID-19 reached the country to prepare an assessment of the impact of the crisis on its economy and labour market and develop a strategy to tackle these impacts. The three-stage strategy to reduce the immediate adverse effects, stimulate the economy and repair the damages was proposed already in early May 2020 (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, 2020[10]). Also, in Austria, researchers were involved in re-designing the ALMP package from the very beginning of the crisis through a standing research committee.

Countries with more flexible ALMP regulations were able to redesign their policies quicker. About one-third of the countries that responded to the survey find that an emergency situation declared by their government or passing particular emergency laws enabled them to adopt the necessary regulations for redesigning ALMPs quickly, without the normal parliamentary process. However, close to one-third of the countries already had very general framework laws for ALMP provision before the crisis, so that introducing and redesigning ALMPs was possible without particular emergency laws. In these countries, adaptions of regulations by their government or ministries was sufficient, or no changes in regulations were necessary at all (the Czech Republic, Malta and New Zealand). Although in total two-thirds of countries regulate the details of ALMP design in lower-level regulations (Figure 3.4), half of them had to still make major adjustments to introduce new schemes. Regardless of how flexible the regulations were before COVID-19, strong political will played a crucial role in many cases to adapt ALMPs to the new needs. The crisis also demonstrated that leaner higher-level ALMP regulations might be desirable as well in a more normal economic situation, to adapt to the continuously changing labour market needs. While the finer details of ALMP design should be flexible and adaptable by lower level institutions, the general framework should be fixed via a parliamentary process to ensure political accountability and democratic processes.

Higher autonomy in PES to decide their operating model and ALMP implementation details has supported responsiveness to local labour market needs and the continuity of ALMP provision despite sudden changes in the working environment. One-third of countries state that high flexibility in ALMP implementation due to their organisational set-up (supported by flexible ALMP regulation) has been crucial in their swift responses to the crisis. Having an autonomous national level PES set up with a supervisory body involving the social partners, is often highlighted by countries as a means to deliver flexible and swift policy responses (in total two-thirds of countries in the middle column in Figure 3.3 stated that some features of their organisational set-up were of key importance). Close to 40% of the countries with a decentralised ALMP system (last two columns in Figure 3.3) note that their set-up enabled fast changes in operating models that took into account local labour market conditions. Mature governance models and co-ordination of activities were critical enablers of this. In countries where a large share of employment services are outsourced, mature and trustful relationships between the ministry and the providers have been key to adapt to the new situation (stressed by Australia and the United Kingdom), involving, for example, changes to the contractual terms agreeable to both parties.

Only a minority of countries exercise a high flexibility of resources to respond to changes in the labour market. Sweden has been successful in amending its ALMP budget in response to COVID-19 faster than other countries as its regulations mean that an increase in long-term unemployment automatically raises funds available both for benefits and ALMPs. Similarly, in the Netherlands, some resources for ALMPs become available automatically for PES when expenditures on unemployment benefits increase. In Switzerland, where cantons are responsible for ALMP provision, ALMP budgets are directly linked to the number of registered jobseekers in cantons and can be adjusted during the year. In Belgium (Flanders), most ALMPs use open budget, which means that additional funds are automatically made available when the needs exceed expectations.

Regarding the flexibility of human resources in PES, close to half of the countries were able to increase their staff numbers in 2020 in response to the crisis and two-thirds made staff re-allocations (mostly for call centres, registering jobseekers, processing benefits, see details in Section 3.3.1). Belgium (Brussels), Croatia, Finland and Slovenia consider the adaptability and devotedness of staff, as well as possibilities to reallocate tasks, to have been key in coping with the challenges of COVID-19 in 2020.

Of all OECD and EU countries, only Israel and Switzerland had a plan prepared before the COVID-19 outbreak to tackle a potential crisis on the labour market that proved to be useful in early 2020. Nevertheless, as the COVID-19 crisis posed challenges that were not foreseen, even these crisis management plans had to be adjusted extensively. Responses to the COVID-19 challenges were facilitated in Austria, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Switzerland, as they had already specific measures in place to tackle an economic crisis situation, which were designed during the GFC or following natural disasters (New Zealand). As the COVID-19 crisis posed challenges to the working environment, countries’ preparedness to respond to the situation was also highly dependent on the level of digitalisation and possibilities to telework. Some countries consider these factors as integral in coping with the new situation.

3.2.2. From crisis management to longer term strategies

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, the PES (and PrES) in all countries needed to switch to a crisis management mode and quickly adapt to the new situation to minimise its impact on employment by delivering ALMPs, processing job retention schemes (see also Chapter 2), minimising delays in benefit payments despite record applications, providing information to jobseekers, employees and employers, and encouraging jobseekers to stay active even when there were fewer vacancies (OECD, 2020[11]). After the initial shock and adjustments in the operating models, countries have started to adjust their medium- and long-term strategies, adapting the basket of ALMPs in line with the changed composition of jobseekers as well as support the speedy recovery of enterprises and ensure effective matching of jobseekers with new job openings.

Responses in 2020 focused on PES operating models

The short-term responses of ALMP systems to the COVID-19 crisis involved above all changes in the operating models of public and private employment services, while the scope for redesigning active support to jobseekers was limited. First, the suddenness of the COVID-19 outbreak and the subsequent restrictions on social interactions imposed a rapid change in working environments and service delivery models. Second, many PES witnessed high inflows of applications for benefits and registrations as well as increased needs for information by the clients (OECD, 2020[11]). On top of that, the approaches taken needed tight monitoring and frequent re-assessments, which required establishment of crisis management systems in many PES, supported by adopting new monitoring tools and dashboards and using data for management decisions more than ever before. Close to 90% of countries responding to the OECD/EC questionnaire highlight the changes in PES operating models as the core parts of their short-term responses to the COVID-19 crisis. More specifically, the key changes involved: i) digitalising processes, boosting remote channels, automating processes for clients and the back-office, ii) simplifying processes for clients and staff, iii) adapting processes to meet health guidelines on the premises, iv) adopting new tools to increase the quality and timeliness of statistics and management information, v) adapting communication to staff and clients, and vi) reallocating staff, increasing staff numbers and training staff to increase PES capacity. One third of countries made more significant changes to ALMP design already in their short-term strategies in 2020.

Medium- and long-term strategies aim at re-designing ALMPs to meet new needs

Most countries had started developing their medium and longer-term strategies of labour market policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis by October/November 2020, but only about half of the countries had already adopted a new strategy. Discussions on the longer-term responses were hindered as day-to-day crisis management absorbed policy makers and implementers throughout 2020. In addition, the health situation, social distancing requirements and the forecasts of the labour market situation kept changing significantly over the year (see Chapter 1), with implications on the appropriate longer-term policy responses.

Compared with the short-term responses, longer-term strategies tend to focus much more on the content of the support to jobseekers, employees and employers, rather than delivery models and PES operating models. The planned changes concern redesigning the basket of ALMPs to match the changed needs of jobseekers and enterprises. All countries responding to the OECD/EC questionnaire that had adopted their longer-term strategy by October 2020, or were to adopt the strategy soon, identified ALMP design and targeting as key components of their plans for 2021 and beyond. For example, Belgium (Brussels) aims to give more priority to the most vulnerable groups, who have suffered more in the COVID-19 crisis and to apply a sectoral approach to employers to meet better the sectoral needs. Belgium (Wallonia) intends to further prioritise individualised approaches to jobseekers, particularly to those who have been recently dismissed, in its new model of “instant support” focusing more on coaching and finding solutions swiftly. Greece is planning to give particular attention to supporting jobseekers from the sectors that have suffered the most in the current crisis, e.g. tourism and culture. Slovenia is trying to increase co-operation with the providers of social services to better support groups that have multiple labour market barriers, and promoting employment of disadvantaged jobseekers (including support with job interviews and post-placement support). Colombia is planning to address the labour market integration challenges of several vulnerable groups, such as youth, older workers, jobseekers from the sectors that suffered exceptionally more due to COVID-19, as well as people working informally. Changes in different ALMPs are discussed in more detail in Section 3.4 of this chapter.

At the same time, still more than half of the countries plan to continue fine-tuning the ALMP delivery models in their longer-term strategies, learning from the experience of 2020. For example, the COVID-19 outbreak led many countries to review and simplify their processes (internally and with clients) and to decrease the level of bureaucracy. Several countries aim to continue making their ALMP design and implementation processes leaner through reviewing structural set-ups, and functions and tasks of all stakeholders involved. Also further digitalisation and automation of processes remain high in the PES agenda, aiming at further increasing PES efficiency (see Section 3.3.2 for more details).

Following an economic downturn like the one caused by COVID-19, ALMPs play a key role in supporting the rapid return to work of the unemployed and the reallocation of labour from declining to growing firms, including across sectors and regions. As has been argued before, this requires countries to adjust existing ALMPs and delivery models or design new ones in an agile manner, as well as additional investments into ALMPs. This section argues that countries need to further scale up their investments in two areas: First, additional expenditure on ALMPs will be needed over the course of 2021 and the years to come to enable public and private employment services to serve a higher number of jobseekers and offer additional support to those who do not return to work quickly. Second, strategic investments into digital infrastructures of employment services are needed to increase ALMP effectiveness and efficiency both in the short and long term.

3.3.1. Scaling up resources for ALMPs

This section provides an overview on countries’ adjustments to ALMP spending in 2020 and 2021, staffing adjustments in PES and the option to complement public provision through contracted provision. While too early to assess sufficiency of public spending on ALMPs in 2020 and 2021, past evidence suggests that there is a clear risk that countries invest too little in this area.

Increasing public expenditure on ALMPs

Evidence shows that spending on ALMPs can help reduce unemployment and long-term unemployment.8 Following the onset of the GFC many countries reacted swiftly with discretionary changes to ALMP expenditure in response to the economic downturn to sustain labour demand and support the unemployed find work. Measures taken by OECD countries as early as 2008/09 included increased funding for their PES and additional investments in ALMPs such as employment incentives, reductions in non-wage labour costs, public sector job creation, business start-up incentives, work experience and training programmes (OECD, 2009[12]).

Countries responded swiftly also to the current downturn and made adjustments to their ALMPs. While some of these adjustments did not require additional funding (e.g. reallocation of staff), most countries increased their funding for ALMPs over the course of 2020 and are planning further changes in 2021. Two principal expenditure categories are distinguished for describing these changes in funding:

Labour market services:9 This includes public provision (or private provision, with public financing) of counselling and case management of jobseekers, financial assistance with the costs of job search or mobility to take up work, and job brokerage and related services for employers, including similar services delivered by private providers but with public financing. Also included is the administration of benefits such as unemployment benefits, job retention schemes and redundancy or bankruptcy compensations.

Active labour market measures:10 These include training, employment incentives, sheltered and supported employment and rehabilitation, direct job creation and start-up incentives, if targeted on the unemployed and closely-related groups such as inactive who would like to work, or employed who are at known risk of involuntary job loss.

Just under two-thirds (65%) of all responding countries increased their budget for labour market services over the course of 2020 (Figure 3.7). For example, in Denmark, the Netherlands and Switzerland the budget for labour market services and active labour market measures automatically increases in line with rising unemployment making the system more responsive to changes in labour market needs (see Section 3.2.1). In many countries additional resources for labour market services were used to hire additional staff to support a higher caseload of jobseekers. In Australia, additional funding was used to enhance the digital service offer for jobseekers. A bolder picture emerges for active labour market measures. Seven in ten countries reported an increase in funding for these types of programmes. For example, Canada more than doubled the funding for the Workforce Development Agreements11 in comparison to the 2018/19 financial year. Hungary increased its expenditure for active labour market measures by 21% in comparison to 2018, Portugal by 30% in comparison to 2018 and Switzerland estimated the increase at around 20%. Details on new or expanded active labour market measures are provided in Section 3.4.

In 2021, just over half (53%) of all responding countries plan to increase the funding levels for labour market services in comparison to 2020, with a similar number of countries (52%) planning an increase in and active labour market measures. A number of countries, however, had to make difficult choices. For 2020, Mexico reported a budget decrease both for labour market services and active labour market measures in order to redirect spending to address priorities and deal with the health crisis caused by COVID-19. In Spain, unused spending on active labour market measures was re-allocated to job retention policies. In 2021, three countries (Hungary, Poland and the Slovak Republic) expect to decrease their expenditure on active labour market measures in comparison to 2020. All three countries reported increases in 2020 and expect to return to pre-crisis levels again. For a full overview of all countries’ spending decisions on labour market services and active labour market measures in 2020 and 2021 see OECD (2021[13]).

While the evidence presented here shows that many countries moved quickly to increase ALMP spending, it is too early to judge whether additional resources made available in 2020 and planned for 2021 were, or will be, sufficient to provide the required level of support to ensure a rapid return to work in the recovery.12 Following the GFC, OECD governments scaled up ALMP spending more strongly than in earlier recessions, probably due to their fuller appreciation of the need to retain an activation stance during a deep recession. Nevertheless, spending per unemployed person declined by 21% on average (in real terms) across the OECD between 2007 and 2010 (OECD, 2012[14]). Larger additional investments into PES and ALMPs may be needed going forward to support the reallocation of labour from declining to growing firms, including across sectors given the persistence of depressed conditions in some sectors (e.g. leisure and hospitality – see Chapter 1). This requires advanced planning, as in contrast to income support policies it may not be straightforward to translate increased funding into higher capacity in the short run. To achieve this, PES need to hire new staff, existing programmes need to be expanded or new ones established, which in turn requires agile systems of ALMP provision, as argued in Section 3.2.

Staff reallocations alleviated initial pressures, but additional PES staff is needed in many countries

The immediate effect of the COVID-19 crisis hit PES when governments introduced lockdowns and social distancing measures in March/April 2020, with the number of jobseekers and applications for job retention schemes rocketing (OECD, 2020[11]) – see also Chapter 2. Sixty-seven percent of countries responding to the OECD/EC questionnaire reported staff reallocations in their PES as an immediate reaction to deal with the most pressing tasks (for information by country see OECD (2021[13])). Often staff reallocations were made to support the handling of short-time work and other job retention schemes, both in countries with pre-existing schemes as well as those that introduced such schemes for the first time (OECD, 2020[15]). Reallocation of staff to help with processing of job retention schemes was reported by Austria, the Czech Republic, Korea, Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Switzerland and Turkey. For example, in late spring 2020, more than 60% of staff in the provincial directorates of the Turkish PES were assigned to payment of short-time working benefits to ensure that payments were processed correctly and paid on time to beneficiaries. Staff were also reallocated to support the processing of unemployment benefit claims and registration of new jobseekers in Finland, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Korea, Latvia, New Zealand and Norway, and to support the contact/call centres in Belgium (Brussels) and Slovenia. During the peak of the crisis, the German PES reallocated up to 20% of its staff.

Staff reallocations have often not been sufficient to ensure service continuity and over half of all countries therefore reacted with hiring additional PES staff over the course of 2020 (for information by country see OECD (2021[13])). In many hiring PES, the new positions are on a fixed-term basis and sometimes involved shifting staff from other public institutions into the PES. New staff have been hired to deal with short-time work and other job retention schemes (e.g. Lithuania, Luxembourg), process the high number of unemployment benefit claims (e.g. New Zealand and Norway), boost call centre support, (e.g. Finland, Luxembourg), provide counselling services to jobseekers and employers (e.g. Estonia, Finland, Ireland, Japan and Korea) and support the further development of online solutions (e.g. Turkey). In most hiring PES the increase in staff over the course of 2020 has been modest, ranging from 1% to 5%. Notable exceptions are Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Korea and Switzerland where PES staffing levels have been increased by 10% or more. Iceland increased its PES staffing by 37% in comparison to the beginning of 2020 and Korea by 79% through fixed-term contracts.

Public employment services are likely to require additional staff in 2021 to deliver high-quality services and have a comprehensive offer of ALMPs for a higher number of jobseekers. Without additional staff, there is a clear risk that PES may not be in a position to offer individual comprehensive support that more vulnerable groups may require (see Section 3.4.3). Among countries responding to the questionnaire almost half (47%) reported plans to further increase PES staff levels in 2021 (for information by country see OECD (2021[13])). For example, the PES in France and the United Kingdom plan to hire additional staff to increase front-line staff in local offices and the new employment programmes for young people, 1 jeune 1 solution (“1 youth 1 solution”) in France and Kickstart in the United Kingdom. The PES in Luxembourg plans to hire new staff in 2021 to guarantee high level of service quality to both jobseekers and employers, as well as to develop new services. The Turkish PES plans to hire additional software developers and IT experts to support the expansion of online services. In many countries PES plans were still under discussion at the time the OECD received questionnaire responses and a number of countries highlighted that hiring decisions depend on the further development of unemployment.

Contracting out employment services as an option to increase capacity in the medium- to longer-term

Many PES face capacity constraints, as inflows of jobseekers applications continue to be high. One option to address the higher and potentially further rising need for employment services is to contract out publicly financed labour market services such as counselling and case management of jobseekers to external service providers. Increased use of contracted provision is likely to be considered mainly by countries with extensive experience in tendering of employment services. While offering the opportunity to scaling up the support for different types of jobseekers, outsourcing of labour market services also carries risks in its design and implementation (Langenbucher and Vodopivec, forthcoming[16]).

Two in five of the countries covered by the OECD-EU survey already contract out employment services to external parties, including both to for-profit and not-for-profit entities. A number of countries foresee expanding the use of contracted out services in the near future. Among them are Austria, Belgium (Brussels), Ireland, Israel, Korea, Sweden and the United Kingdom, and (potentially further into the future) Slovenia. Austria and Belgium (Brussels) recently expanded the use of contracted provision to support displaced workers who lost their jobs due to business closures or other economic reasons and other groups at risk (see Box 3.2).

A number of countries use some form of contracted-out provision for all types of jobseekers (e.g. Colombia, Denmark, Italy, Norway, Sweden) or particularly job-ready jobseekers (e.g. France). Other countries outsource specialised support to specific target groups, including young people (e.g. Korea, New Zealand), persons with a disability or a health condition (e.g. the United Kingdom (England and Wales)), older jobseekers (e.g. Austria, Belgium (Brussels)) and long-term unemployed (e.g. Ireland and Poland). Following the GFC, large-scale programmes using contracted-out employment services to support a high number of long-term unemployed back into work have been introduced in the United Kingdom in 2011 (Work Programme; (OECD, 2014[3])) and Ireland in 2015 (JobPath; see Box 3.3). Both programmes ran over a period of five years. Building on the experience with the Work Programme, the British Department for Work and Pensions has already started the commissioning process for a new programme in England and Wales, called Restart, which will go live in summer 2021.

Corona-Joboffensive (“corona job initiative”) in Austria

With the Corona-Joboffensive the Austrian Government introduced a new funding package with the aim to support over 100 000 participants from October 2020 onwards, including unemployed seeking professional reorientation or further training, unemployed young adults without a qualification, women re-entering the labour market, workers at risk of displacement and other target groups (e.g. persons with disabilities, persons with language-related employment barriers and people with complex needs). The new package combines a number of different measures, most of which are outsourced to contracted providers, including both not-for-profit and for-profit entities. Amongst the measures are:

Professional guidance and counselling for education and career planning, taking into account individual requirements.

Labour market training to support upskilling and reskilling in growing occupations and sectors with a focus is on digitalisation; science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM); the green economy; and the care, health care and education sectors.

Participants who complete a qualification measure or (re)training under the corona job initiative that lasts longer than four months receive an education bonus (EUR 180 per month) in addition to their regular unemployment benefits.

Rebond.brussels (“Rebound Brussels”) in Belgium

The PES of the Brussels region in Belgium set up the new Fonds Rebond in response to bankruptcies in the Brussels region since the start of the COVID-19 crisis. Workers made redundant by a Brussels employer following a bankruptcy declared after 1 July 2020 have access to this free service on a voluntary basis1 to support their re-integration into the labour market as quickly as possible. The programme lasts up to 12 months and consists of two components:

Social component: it supports participants with benefit claim procedures and informs them about mutual obligations attached to unemployment benefits.

Employment component: participants have a personal coach who supports them with counselling, skills assessment, and career advice and helps access other support that is part of the programme, such as workshops and training.

The employment component is provided either by an existing provider of the PES or by a specialised outplacement office. The choice of the service provider depends on several criteria such as age, employment history and career goals.

← 1. Participation in outplacement services is mandatory for displaced workers aged 45 and over and at least one year of seniority with the employer declared bankrupt. Refusal may result in benefit suspensions ranging from 6 to 52 weeks.

Source: Bundesministerium für Arbeit (2020[17]), “Die Corona-Joboffensive”, https://www.bma.gv.at/Services/News/Coronavirus/Corona-Joboffensive.html and Actiris (2020[18]), “Bénéficier de Rebond.brussels”, https://www.actiris.brussels/fr/citoyens/beneficier-de-rebond-brussels/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

Following the GFC and the sovereign debt crisis, unemployment and especially long-term unemployment reached very high levels in Ireland. Staff-to-client ratios at the Irish Public Employment Service (PES) of around 1:500 remained far too high. While there had been efforts to increase the number of PES counsellors, financial and recruitment constraints limited the degree to which PES services could have expanded further. Against this background, the Irish Department of Social Protection prepared for large-scale contracting out of employment services targeting the long-term unemployed through the JobPath programme. JobPath was the single biggest contract for employment services of the Irish state. Long-term unemployed were referred to contracted providers between mid-2015 until end-2020 through a randomised referral mechanism. The programme applied to all of the Republic of Ireland, which was divided into four contract areas and eventually delivered by two providers only (each operating in two contract areas). The payment model was characterised through a high outcome-based component providing strong incentives to achieve sustained employment for the participants (the maximum fees per clients could only be claimed after 52 weeks of employment). A set of minimum services requirements guaranteed one-to-one meetings with a counsellor at least every 20 days while the participants were unemployed, development of a “Personal Progression Plan”, quarterly in-depth review meetings and in-employment support for at least the first 13 weeks of employment.

A counterfactual impact evaluation of JobPath, exploiting the random referrals to the programme, found that unemployed who participated in JobPath in 2016 were 20% more likely to move into employment in 2017 than without JobPath, and 26% more likely in 2018. JobPath participants who found a job also earned 16% more per week in 2017 and 17% more in 2018 than the comparison groups (long-term unemployed not (yet) referred to JobPath). This means that, on average, individuals who benefited from JobPath in 2016 had earnings from employment that were 35% higher than they would have been without the programme in 2017 and 37% higher in 2018. What is more, positive effects were found for all participant cohorts, including those furthest from active participation in the labour market. Qualitative surveys of JobPath participants also revealed good performance of JobPath providers. More than half of the participants felt that the contracted providers offered services similar or better than comparable PES services.

Source: Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection (DEASP) (2018[19]), “Satisfaction with JobPath service providers (Online research 2018)”; DEASP (2019[20]), “Satisfaction with JobPath service providers (October 2018, Phone)”; Department of Employment Affairs and Social Protection (2019[21]), “Evaluation of JobPath outcomes for Q1 2016 participants”, DEASP Working Paper, Dublin; and Intreo (2014[22]), “Pathways to work 2015”.

3.3.2. Harnessing technology to increase ALMP effectiveness and efficiency

The utilisation of digital tools has been a cost-effective method to deal with increased demand for services and reduced physical capacity. More sophisticated digital tools, that are now becoming more widespread in PES, offer further advantages in tailoring services to clients, increasing efficiency and facilitating self-service amongst clients. However, care will need to be taken to ensure that all processes designed as short-term fixes to acute demand pressures are reviewed to ensure they are fit for purpose for the longer term.

Remote channels have been crucial to maintain services

Facilitating greater use of technology and expanding services beyond traditional face-to-face settings have been features of many PES strategies long before the current pandemic. However, the severity of the recent face-to-face restrictions forced PES to scale up and adapt this capacity at an unprecedented pace. They also represent a unique opportunity for PES to seize this momentum and advance a step-change in technology utilisation, to better serve their customers as they continue into a post-pandemic world.

Figure 3.8 shows the dynamics of PES digital and remote access to services. Prior to the pandemic, on average, around half of PES offered remote access across the range of activities undertaken. Subsequent to the social distancing restrictions imposed due to COVID-19, this has increased to around 80% and the variation in remote access between activities has dropped. Of those PES offering remote access to services prior to the pandemic, 42% have augmented delivery subsequent to it. The strides made in extending remote and digital access by PES in less than one year, almost surpasses the totality of that access that was built up prior to the pandemic. Across the nine activities surveyed, 60% of countries had made changes to facilitate remote access across five or more activities. Those countries with good remote access prior to the pandemic (e.g. Belgium (Flanders), Estonia and Sweden) had to make relatively few changes to their delivery, compared to those with relatively little previous remote access (e.g. Spain having made changes to the entire suite of activities surveyed).

The recent introduction of remote access by some PES and the expansion of it by others suggests there is still much development – to both scope and content – that can be achieved, building on recent successes. It is important to note that whilst PES have increased their ability to deal with customers remotely this was often piecemeal, designed to meet the immediate pressures of COVID-19 inflows. This included allowing customers’ registrations via paper applications sent by ordinary mail and applications via email and by phone. Others streamlined their existing digital channels to remove some face-to-face contact. The challenge for PES will be to review their processes subsequent to the pandemic and to design remote and digital channels that offer streamlined and future proof delivery. Some of the shortcuts to registration may have weakened checks and balances on fraud and error, a compromise to ensure that speed of support to individuals was maintained. Work will need to be undertaken to review the impact of the changes made, so that integrity of benefit administration is maintained when we move beyond the pandemic.

Digital channels and automation provide efficient service capacity to PES

The speed at which the pandemic unfolded and the impact of social distancing restrictions, brought an abrupt halt to face-to-face delivery of services across OECD countries. Increased digitalisation of services helped PES mitigate the impact in several ways:

Teleworking arrangements for staff in front and back-office functions allowed service continuity, protected workers and maintained capacity where the physical demands of social distancing reduced available office capacity (European Commission, 2020[23]; ILO, 2020[24]).

Remote channels for ALMP provision have allowed continuation of counselling, career guidance, job matching and training via online channels. Interactive service provision such as counsellors interacting with a client via an online channel (e.g. in the United Kingdom via the Universal Credit “journal” where caseworkers and clients can interact with one another) has been supported with more “static” online support (information on PES websites, general guidelines for job search, videos for training etc.).

Remote benefit applications and jobseeker registrations (remote channels and user-interfaces enabling jobseekers to send or upload their data to PES IT systems) have protected customers by limiting social exposure risk and facilitated the speed and volume of applications.

PES that offered comprehensive e-services for clients, in combination with automated back office systems, were able to almost fully serve their clients without the need for personal interaction (e.g. Estonia, Belgium (Brussels and Flanders), Iceland, the Netherlands, Norway the United Kingdom). This served twin benefits: i) to facilitate quick and easy application for benefits, critical for individuals and families to meet their sustenance and security needs; and ii) to allow PES to reserve what little face-to-face capacity they retained for their most vulnerable customers. PES with more advanced digital capacity were able to preserve their capacity for ALMP delivery. For example, the Estonian PES was already providing career counselling via Skype prior to the pandemic, allowing them to seamlessly continue high quality service provision to their customers as the pandemic hit (Holland and Mann, 2020[25]).

Whilst digital penetration is now much higher among PES (see Figure 3.8), there are still some PES that do not offer such access across a majority of services. An important element of digital strategies will be to embed the use of e-services as the default mode for registration and administration of benefits (e.g. already in Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway) also beyond the pandemic. In turn, it is important to reserve face-to-face interaction for those clients without digital skills or with complex needs that may necessitate personal contact. ALMP provision should rely on a combination of digital and face-to-face support, depending on the specific needs of target groups and the services and measures in question. Careful evidence building is required before moving to broader digital provision of ALMP in the longer term. Previous evidence has shown that there can be some risk to channel shift in delivery, so building theories of change and testing the impact of digital delivery on outcomes should be incorporated prior to any shift. For example, the reform in Finland in 2013 substituting face-to-face counselling with online counselling in 60 municipalities, has been estimated to have increased unemployment length by 2-3 weeks (Vehkasalo, 2020[26]). The importance of channel management to fit to the target groups has been demonstrated also in Austria, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (Middlemas, 2006[27]).

It is vital that PES continue to develop their technological capacities so that they may design and implement digital services at the heart of their offer going forwards. This will require a continued investment in IT infrastructure to allow both PES employees and customers to seamlessly utilise all the tools at their disposal. It should be designed with the service users’ needs at the centre. Case workers should be able to easily review customer circumstances, skills and experience, match them to vacancies and use them to provide well-targeted ALMPs. PES customers should be able to easily navigate the information, support and training available to them and to select the best available vacancies. For example, the PES of Belgium (Flanders) restructured its product development so that the customer is at the heart of the design and implementation process and any application not used sufficiently by customers after its implementation is now discarded (Peeters, 2020[28]).

PES should also consider the most appropriate co-ordination of data and services across national and local agencies, to ensure that data can be linked and shared and service provision tailored for maximum effect. PES that can link customer data to benefit, income and employment records and to local and national training provision and vacancies, will be able to cross-use the data and increase efficiency for customers. For example, the move to Universal Credit in the United Kingdom means that customers no longer have to make separate applications for five different benefits, particularly useful for people that cycle into and out of work frequently.

There will always exist a group of customers for whom a purely digital and/or remote offering is not appropriate and PES should retain some face-to-face capacity to ensure continued support for these customers. At the same time, with a fuller digital capacity for society as a whole, PES should – in collaboration with other responsible agencies – seek to equip those without digital capability with the tools to enable them to participate. This will require not only training in digital skills and IT but also access to the necessary equipment to do this. For example, through labour market transfer agreements, Canada has provided provinces and territories, who design and deliver training and employment programming, with the flexibility to use federal funds to provide IT equipment and internet access to learners that may have otherwise been excluded from participation. This is particularly important as those individuals without this access are also those who may benefit the most from it (for example, older workers, migrants or those with fewer skills). Colombia has also sought to include people without access to computer equipment or with limited internet connection (such as students living in rural and remote areas) by introducing tools such as pre-recorded classes, tutorial videos, groups on messaging applications, emails, video calls or phone calls.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) can enhance service delivery going forwards

The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) practices and advanced analytics can help PES manage their COVID-19-related caseload in the short term and build capacity to improve longer-term outcomes. However, care needs to be taken to protect service users in the design and implementation of any service improvements via the use of AI and algorithms for decision-making and sufficient heed paid to the equitable assignment of customers to provision, based on digital recommendations. Functionality will need to be designed to protect user data, compliant with data protection regulations. Box 3.4 discusses the various aspects of ALMP provision that AI and advanced analytics can facilitate in more detail and provides some country examples. PES that had already begun to utilise AI in their work will be better placed to mitigate the extra burden placed upon them by increased numbers of jobseekers, principally along three dimensions:

Better matching workers to vacancies: In a period of accelerated structural change, AI can facilitate better matching of individuals to vacancies, particularly through the assimilation of data on jobseekers’ existing skills. Learning algorithms can spot emerging patterns that may speed up the reabsorption of displaced workers into industries requiring similar skillsets – see also Chapter 1 and OECD (2021[29]) – and AI can quickly process large pools of jobseekers. Usage of click data may also help to identify how workers search for vacancies to improve recommendations for new jobseekers.

Better tailoring of services and ALMP: Not only has COVID-19 substantially increased caseloads of jobseekers across countries, it has also altered their composition, as some groups have been affected more by the current health and economic crisis than others (Chapter 1 and Section 3.1). This may result in traditional profiling tools used by PES – either digital or via caseworker assessment – becoming less accurate as they are dealing with unknown individuals. AI algorithms allow for rapid and consistent adjustment of profiling based on the new information on these individuals, meaning that services can be adapted and deployed at scale and with pace.

Greater efficiency and increased “self-service”: The demands placed upon many PES by the rapid influx of new jobseekers mean that support had to be rationed, as there are fewer staff per jobseeker. The provision of virtual job coaching via the use of AI means that PES with this capacity can facilitate fast and accurate matching and job finding for individuals that are potentially easier to place in the labour market, reserving the support of case workers for those in greater need. This has potential benefits to both the efficiency and equity of PES services.

It is important to note that due to the relative infancy of PES offerings in the AI space, there is a scant literature of robust impact assessments. Therefore a crucial part of offering these services in the future will be to ensure they are evaluated and properly scrutinised alongside existing service provision. There is a trade-off between accuracy and equity in algorithmic assignment which may lead to unintended discrimination between individuals (Desiere and Struyven, 2020[30]) without proper consideration and discussion of risks. In the absence of complete information, some things that are observed (like ethnicity or socio-economic status) may be confounded with unobserved data (like motivation or intrinsic ability). It is likely that data underlying algorithmic assignments is insufficient to generate completely socially equitable outcomes, at least in the medium term. Therefore a human backstop is essential to review and monitor implementation of policy via these channels and rigorous evaluation conducted to support this.

Combined technological advances in data capture, storage and processing, offer a multitude of potential tools for PES to address:

Automation of application processing – Fully automated processes without human involvement to make decisions on eligibility to register or granting a benefit based on information provided on the application and pulling data from registers (e.g. Estonia). This can also involve, or be supported by, AI tools to detect fraud and tools for quality assurance (comparing data from different sources, potentially also using predictive analytics).