23. Montenegro profile

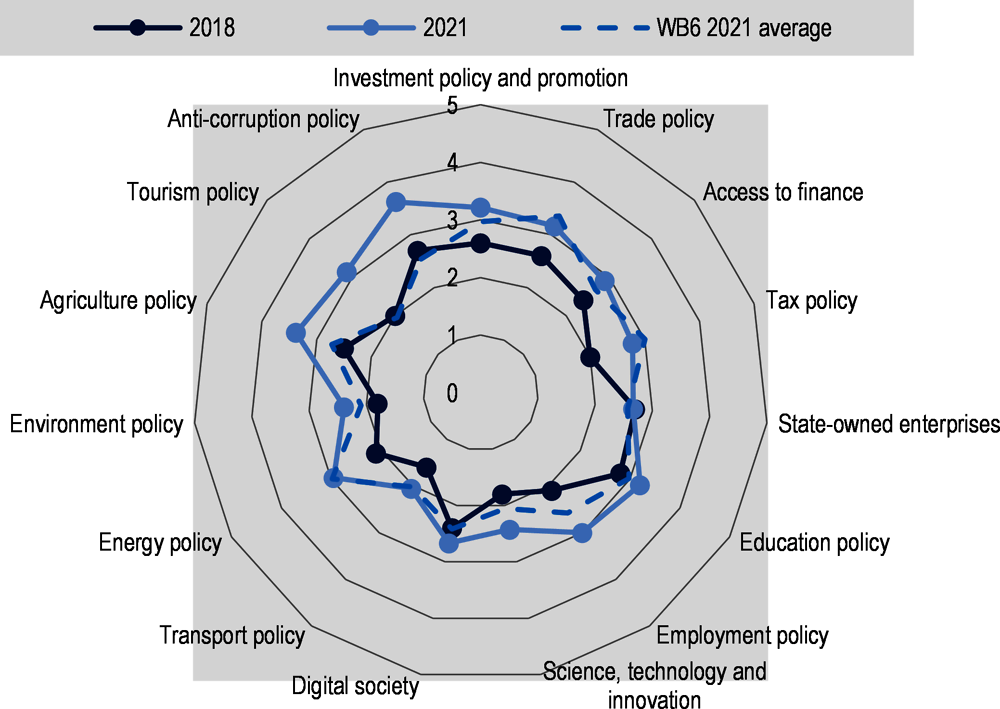

Montenegro has made progress since the publication of the Competititveness Outlook 2018 report in all the policy dimensions with the exception of State-Owned enterprises (Figure 23.1). Most of the improvements have been in the legal and regulatory environment, which forms a solid basis to improve the overall competitiveness of the economy. Its main achievements are as follows:

Significant new tax measures have aligned Montenegro’s tax system with recent international tax trends and have strengthened the scope for international tax co-operation. The economy joined the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Sharing in December 2019. The OECD Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes has started a peer review of Montenegro’s readiness to exchange information on request (EOIR). Montenegro also signed the Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters in October 2019 and is in the process of amending its transfer pricing rules via a reform of the Law on Corporate Profit.

School participation levels are increasing. As of 2019, Montenegro had achieved net universal primary school enrolment (99.9%), though lower secondary education is not quite there yet (92.3%). Net enrolment in upper secondary education (89%) has gradually increased and is on track to meet OECD (92.5%) and European Union (93%) averages in the coming years. Moreover, Montenegro has one of the lowest early school-leaving rates in the region (5% in 2019), well below the EU target of less than 10% of early school leavers by 2020.

Labour laws are aligned with EU standards. Labour market flexibility and labour standards for workers in certain fields have improved. In addition, the capacity of the public employment services (PES) has been strengthened, in particular by improving the tools and instruments available to PES counsellors, such as a profiling tool for the unemployed.

The science, technology and innovation (STI) policy framework has advanced significantly. Montenegro developed a set of guidelines for smart specialisation in 2018, and is the first of the six Western Balkans (WB6) economies to adopt a smart specialisation strategy (covering 2019-2024), which received a conditionally positive assessment by the European Commission services. Action plans are in place to support implementation of the strategic framework, and budget allocations have increased in recent years. A new Law on Incentive Measures for Research and Innovation Development and a revised Law on Innovation Activity strengthen the legal framework for STI.

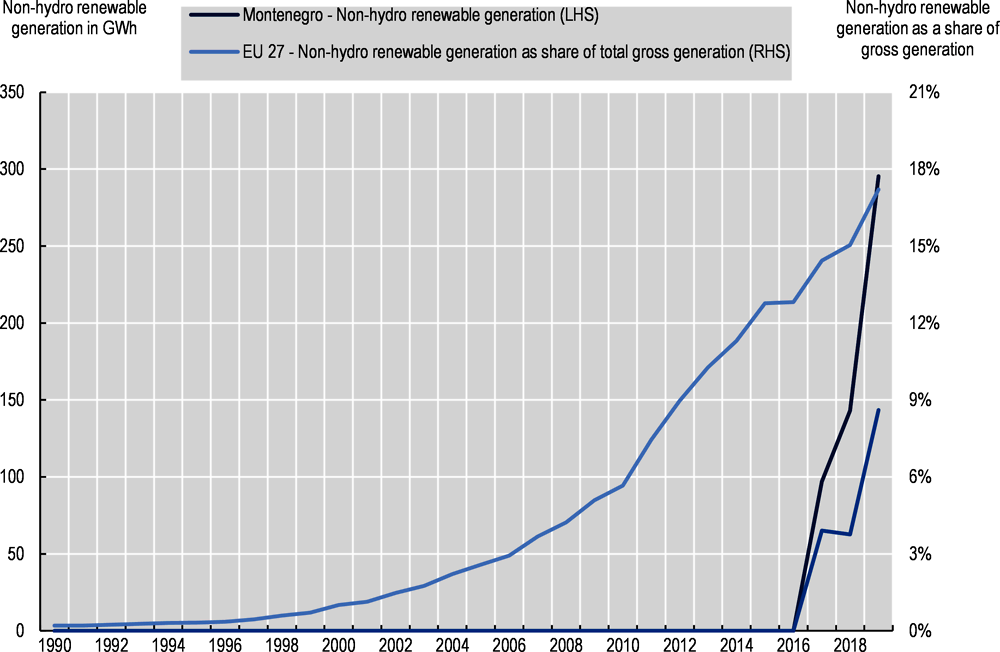

The energy sector is guided by a comprehensive energy policy. Three of the four pillars of the EU’s Third Energy Package (transparency, non-discrimination and a strong regulatory framework) have mostly been implemented. This is confirmed by the Energy Community, which rates Montenegro as the highest performer in the Western Balkans regarding transposition and implementation of the Energy Package. Recent changes to the Energy Law have removed the requirement for government consent to the statute of the regulator, which is a step towards reducing the risk of political influence over the regulator and reaffirms its independence.

Tourism destination accessibility has increased. The economy has expanded the eligible categories for removing visa requirements and adopted special regimes for border crossings for tourists during the high season. Accommodation capacity and quality has improved through measures to facilitate investments in high-quality accommodation, and a consistent accommodation quality standard framework based on EU standards.

Agro-food system regulation has improved. Notably, phytosanitary and veterinary standards have been further harmonised with EU standards. Several regulations on seed products were updated in 2019, and there has been continuous improvement in harmonising by-laws and rulebooks on product regulations with EU directives.

Priority areas

While Montenegro did not score below the WB6 average in 13 dimensions of the 15 policy dimensions scored in the assessment, there are several areas in which Montenegro still needs to step up its efforts (Figure 23.1):

Improve investment promotion and facilitation. The recently established Montenegro Investment Agency (MIA) does not have a formal mandate to provide aftercare services. The government needs to clearly define the MIA’s responsibilities for aftercare services, notably by expanding the agency’s mandate and/or producing a clear system for enquiries. Providing aftercare services will require strong co-operation with other institutions and regulatory bodies. The many current incentives could prove difficult to navigate for foreign investors. Increasing the clarity and awareness of these incentives through more transparent qualification criteria, and targeting foreign investors through awareness-raising campaigns, would be beneficial for the overall competitiveness of the economy. The government should also reinforce mechanisms for evaluating the cost and benefits of the incentives, their appropriate duration, and their transparency.

Introduce alternative equity-based finance. Businesses’ access to finance heavily relies on bank lending. The use of alternative equity instruments, such as initial public offerings, business angels and venture capital, is limited. Integrating crowdfunding into the legislative framework could provide a feasible alternative source of finance. In addition, conducting awareness campaigns on the existence of capital markets and the advantages they offer to firms could also help to enhance the existing structure.

Review the effectiveness of the current state ownership arrangements and develop a state ownership policy. Montenegro has not yet developed an overarching ownership policy for state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that lays out why the government owns companies and how it expects them to create value. While ownership rights exercised at different levels that have diverse competencies (e.g. government, state funds, line ministries), the authorities should ensure that these state actors operate under a unified ownership policy. Given that the authorities have chosen to prioritise private investments in their SOE sector, they should review the need for the state to continue holding minority shares and also produce an aggregate report on the performance of the state’s portfolio.

Continue to boost investment in the scientific research system. With 734 researchers per million inhabitants, the number of researchers in Montenegro is much lower than the EU average (4 000 researchers per million inhabitants). More comprehensive measures should be put in place to build human resource capacity in priority STI areas and increase the attractiveness of research as a profession. Moreover, Montenegro should continue building a national and regional research infrastructure. Timely completion of the Science and Technology Park in Podgorica and affiliated impulse centres, coupled with sustained funding, will improve integration between academia and the private sector. Efforts should also be made to get the pilot technology transfer office at the Centre of Excellence at the University of Montenegro up and running.

Strengthen programmes for the digital transformation of the private sector. The budget and the number of businesses applying for digital transformation programmes remain relatively low. Moreover, despite the proliferation of ICT training programmes, their lack of relevance to industry is widening the gap between the skills available and those sought by ICT sector companies. Developing a common digital competence framework for ICT professionals would help to meet the needs of the labour market. The government needs to review and evaluate existing support programmes to promote the adoption of e-business and e-commerce by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and to identify areas for improvement. In doing so, greater co-operation between ICT training providers and the private sector should be systematised following EU and international good practices

Introduce a land-use management framework. Although there is a regulatory framework related to land-use management in place, little progress has been made to implement it. The pressure on land and soil resources is growing, especially in the context of a pronounced decrease in agricultural land, from 38% in 2012 to 18.5% in 2016. While the use of agricultural land is regulated by law, the legal framework does not prescribe the maximum concentrations of hazardous and harmful substances allowed on other types of land (industrial land, playgrounds, parks or residential areas). Montenegro needs a clear policy framework for cleaning up contaminated land, as well as concrete guidelines to help identify land that needs decontaminating.

Key economic features

Montenegro is a small service-based economy with a large tourism sector. In 2019, services accounted for 58.7% of gross domestic product (GDP) and 73% of employment in Montenegro, with the highest contributions coming from wholesale and retail trade, accommodation related to the large tourism sector, real estate, and transportation and storage. Over the past decade, the services sector’s GDP contribution has expanded considerably at the expense of both industry and agriculture. The GDP share of industry, including construction, declined from 22.3% in 2001 to 16.1% in 2019, while its contribution to employment declined from 25% to 19.1%. Currently manufacturing accounts for just 4% of GDP and 6.4% of employment. Meanwhile, the contribution of agriculture, forestry and fishing to GDP has nearly halved since 2001, from 10.8% to 6.4%. Today this sector accounts for just 7.8% of employment, the smallest contribution in the Western Balkan (WB) region (World Bank, 2020[1]).

As a very small economy that is open to trade and capital flows but that lacks an independent monetary policy,1 Montenegro is highly vulnerable to external shocks and business cycle fluctuations. As a result, the growth of its economy has been more volatile than the other WB economies. For example, in the run-up to the global financial crisis between 2005 and 2008, the Montenegrin economy was expanding at an average annual growth rate of 7.5%, well above most regional peers (World Bank, 2019[2]), on the back of a credit boom fuelled by high capital inflows (46% of GDP at their peak in 2008). During this period, progress on the privatisation and structural reform and business-friendly environment agenda helped to attract considerable foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio investment. However, the bust that followed the global financial crisis, when capital inflows declined dramatically, was much bigger than in neighbouring economies, resulting in a GDP contraction of 5.8% in 2009. Similarly, Montenegro experienced a more severe recession (2.7% decline in GDP growth) in the wake of the Eurozone crisis in 2012 (World Bank, 2019[2]). The most recent economic contraction caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is estimated at 15.2% in 2020, much more substantial than in the other WB economies (EC, 2020[3]). The low fiscal space and limited room for discretionary fiscal spending, especially in the wake of the current crisis, further limits the public sector’s ability to absorb these external shocks.

Over the past few years, while growth has been buoyed by significant infrastructure investment and strong consumption growth, substantial imbalances have persisted. Gross fixed capital formation rose from 20% to 27% of GDP between 2013 and 2019 on the back of high growth in public infrastructure investment (mainly the Bar-Boljare Highway), as well as significant private investment in energy and tourism infrastructure. Public consumption has also contributed strongly to GDP growth despite fiscal consolidation. Export performance has also improved in recent years. Exports’ contribution to GDP rose modestly from 40.6% in 2014 to 43.7% in 2019 (Table 23.1), supported by the tourism sector, which accounts for roughly half of total exports. However, the domestic production base remains low and consumption and investment are highly dependent on imports, which has led to persistently high external imbalances. The trade deficit in 2019 amounted to 21% of GDP, and the current account deficit has exceeded 15% of GDP throughout the last five years (World Bank, 2020[1]). These external imbalances have been exacerbated significantly by the COVID-19 crisis (see the COVID-19 section below).

Montenegro also suffers from a relatively undiversified export base, adding to its vulnerability to external shocks. Goods exports, which account for 14% of total exports (MONSTAT, 2019[4]), include mainly metals, which are highly susceptible to price fluctuations and offer relatively little in terms of value-added. Service exports are meanwhile dominated by travel and tourism services (65% of total service exports) (World Bank, 2019[5]), which are highly susceptible to external shocks, as witnessed during the latest crisis (see the COVID-19 section below).

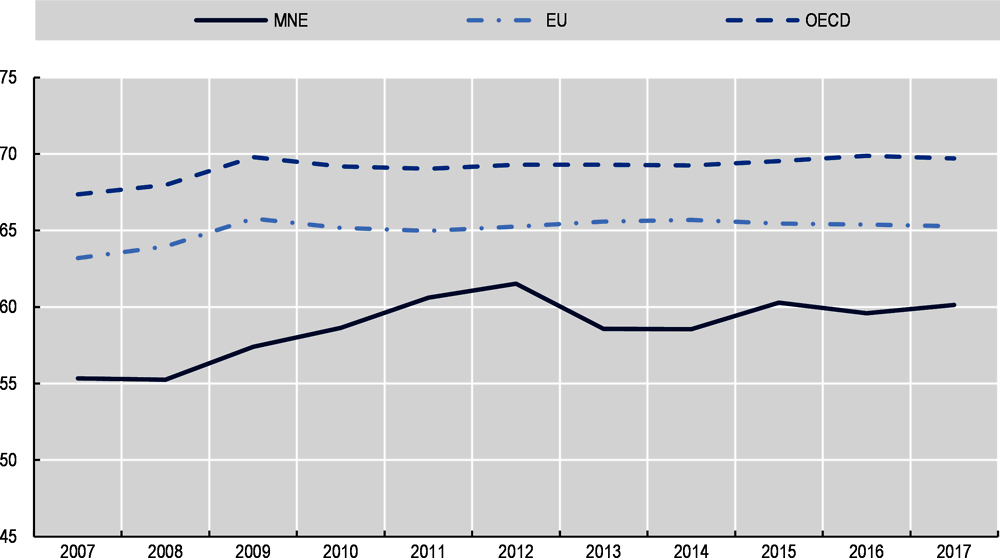

Despite the strong growth, labour market challenges have persisted. At 64.8%, the labour market participation rate is low compared to the EU average of 73.3%, and lower than most other Western Balkan economies (World Bank, 2019[6]). The participation rate is particularly low for youth (36.5%) (World Bank, 2019[6]) and women (57.9%) (World Bank, 2019[7]). Unemployment remained high at 14.9% in 2019, particularly among the youth (29.3%) (EC, 2021[8]). The crisis has further exaggerated this challenge, with unemployment rising to 18.4% in 2020. Finally, the gains in employment over the past few years have been rather limited for vulnerable groups (World Bank, 2016[9]). The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted how labour market challenges stem from an insufficiently diversified economy that is more susceptible to external shocks (see the COVID-19 section below).

Long-term GDP growth and employment prospects are hampered by weak productivity, which reflects significant and deep-standing structural challenges in the economy. Labour productivity, measured as output per worker, is considerably lower than the EU average. The productivity gap is the largest in the services sector, which employs the highest share of the labour force in Montenegro. Here the output per worker is more than four times lower than the EU average (World Bank, 2019[10]). The weak productivity growth in spite of significant capital accumulation over the past decade also points to weaknesses in the efficient use of this capital. Significant outstanding structural challenges explain these outcomes, including an inadequately skilled labour force, limited access to finance for SMEs, corruption and informality – see Structural economic challenges. The high increase in wages, which has outpaced the growth in productivity, has weakened competitiveness over the past decade (World Bank, 2016[9]).

Improving the skills of the population and enhancing the prospects for the low-skilled and poorest groups are the most critical challenges for ensuring sustainable and inclusive long-term growth in Montenegro. In light of the unfavourable demographic trends and high outmigration – with emigrants making up 20% of the resident population (ILO, 2019[16]) – especially by high-skilled workers, the importance of strengthening labour productivity is critical. This will require rectifying the weaknesses in the education system in order to provide adequate and sufficient skills to meet the needs of the labour market; strengthening active labour market policies; and supporting adult education in order to create a nimbler workforce. Strengthening social safety nets whilst also expanding the employment opportunities of low-skilled workers will also be critical in ensuring that growth is more equitable and sustainable.

Strengthening the institutional environment and easing the outstanding frictions in the business climate will also be essential for strengthening SME investment and growth and attracting FDI in manufacturing and service sectors with high export potential. This includes tackling corruption, further improving public services, reducing the administrative and regulatory burden on businesses, and tackling the still relatively widespread informality.

Last but not least, boosting macroeconomic growth and ensuring that it is more balanced and less volatile will also require stronger fiscal and financial policies. In the short to medium term this would entail fiscal consolidation and reducing the relatively large public debt that has further increased in the wake of the COVID-19 economic crisis. Ensuring long-term growth will also require removing structural obstacles to countercyclical fiscal policy development, which are critical in the context of the limited monetary policy options for addressing external shocks. In the same context of limited central bank tools for influencing the credit flow in the economy, strengthening financial supervision will also be important for ensuring macroeconomic stability.

Sustainable development

Over the past decade, Montenegro has made progress towards the targets of Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, but considerable challenges still remain in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as shown in Table 23.2. Montenegro is on track to achieve or has maintained the achievement of the SDGs in only two main areas: 6 and 17 – clean water and sanitation and partnerships for the goals. However, even in these areas some challenges persist.

There has been moderate improvement in many areas. In the area of poverty, while the headcount ratio of those living on USD 1.90 per day is lower than the SDG target, the target for the headcount ratio of those living on USD 2.30 per day has not been achieved. Health outcomes have been improving, but the death rates due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and other non-communicable diseases are still above the targets. In the area of quality education, the SDG target of 100% of net primary enrolment has been achieved, but at 89.9% the lower secondary completion rate has decreased. In the area of affordable clean energy, access to electricity is high but challenges persist in accessing clean fuels and technology. High unemployment remains an important challenge despite progress achieved over the past decade. The share of the population using the Internet and with mobile broadband subscription has increased, but limited investment in research and development (R&D) is holding back progress towards the SDG on industry, innovation and infrastructure. Finally, in the area of peace and institutions, more progress is needed to reduce corruption, eliminate child labour, as well as improve property rights and the freedom of the media (Sachs, 2021[17]).

Progress towards a number of SDGs has stagnated. In the area of gender equality, significant challenges remain in access to family planning and the ratio of female-to-male mean years of education received has decreased. Air pollution and insufficient quality of the public transport network negatively impact the quality of city life. More action is also needed to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, particularly those stemming from energy use (Sachs, 2021[17]).

The most significant challenges according to the SDG assessment lie in the areas of inequality, responsible production and consumption, and life on land and below water. At 40.5, the Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality, is still well above the target value of 27.5. Montenegro continues to produce significant amounts of waste, and recycling and reuse remain limited. Last but not least, significant efforts are needed to protect terrestrial and marine biodiversity and reduce terrestrial and marine pollution (Sachs, 2021[17]).

Structural economic challenges

Montenegro faces a number of key structural challenges that undermine its competitiveness, productivity, investment and exports.

Skills gaps are a key obstacle to employment

Skills gaps contribute to unemployment and undermine economic upgrading. Despite high spending on education, which at 4.5% of GDP is nearly on a par with OECD economies, Montenegro’s relatively weak student performance in international standardised tests points to considerable gaps in the provision of quality education. For example, in the latest Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), just over 50% of students achieved the minimal level of proficiency in the three testing subjects (reading, mathematics and science), which is well below the OECD average of over 75% (OECD, 2020[18]).

Skills mismatches negatively impact employment as well as firm growth. This is a particular challenge for innovative firms, 45% of which reported that a lack of skills was a problem in filling skilled manual labour vacancies (World Bank, 2018[19]). An inadequately educated workforce was also identified as a challenge by 10% of firms (World Bank, 2019[20]). Soft skills including language, leadership, critical thinking and initiative were the key missing skills, but many firms also cited challenges in hiring due to lack of technical skills (World Bank, 2018[19]). A study by the European Commission’s Directorate General for Education and Culture (DG EAC) has found that for every ten students that enter the education system in Montenegro, only two find a well-matched job. Low-skilled workers face the biggest challenges in finding employment – the number of unemployed people in this category has tripled between 2013 and 2017 (ETF, 2019[21]).

Low labour force participation, particularly among young people and women, brain drain and the ageing population exacerbate skills-related challenges and weaken long-term growth prospects. The capacities of the youth are particularly underused as the share of young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) remains high at 17.3%, while the youth labour force participation rate is low at just 37%. Female activity rates also remain below aspirational peers in the EU at 58%, reflecting constraints related to child-care and traditional values and norms regarding women’s place in society. With many high-skilled workers emigrating to more developed countries, and in light of the shrinking labour force, addressing the skills challenges is of utmost importance for setting Montenegro’s economy on a higher and more sustainable long-term growth path.2

The business and investment climate faces persistent challenges

Montenegro has significantly improved the business and investment climate, yet some notable challenges persist. Thanks to reforms that reduced the regulatory and administrative burden on businesses, Montenegro currently ranks 50th out of 190 economies in the World Bank’s Doing Business report (World Bank, 2019[22]). Nevertheless, there are some areas where further progress is needed in order to create an environment conducive to investment and enterprise innovation, internationalisation and growth.

Starting a business in Montenegro is more difficult than in most economies around the world. The process entails more procedures (8 compared to the 4.9 OECD average and 1 for the global leaders) and is more time-consuming than in other economies (12 days in Montenegro vs. 9 for the OECD average and 0.5 for the highest performers). Obtaining an electricity connection is also more costly and time-consuming: it takes on average 131 days in Montenegro to get connected, compared to 75 days for the OECD and 18 days for top performers. The cost is also more than twice as high as the OECD and well above the no-cost benchmark of the top performer (World Bank, 2019[22]).

Corruption remains an important challenge for doing business in Montenegro. In the latest Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS), Montenegrin firms reported an above-average incidence of bribery and share of public transactions that require an informal gift compared to global and Europe and Central Asia region peers. The highest share of firms that responded to the survey noted expectations of gifts for obtaining licences and permits and for meetings with tax officials (World Bank, 2019[20]). Incidentally, Montenegrin firms are more likely to have to meet tax officials in person than in other peer economies.

Informal sector competition represents an important constraint for businesses in Montenegro. In the latest enterprise survey, 58% of firms stated that they compete against informal competitors, and nearly a quarter of all firms identified informal competition as a major obstacle for their business. The impact is highest among SMEs, particularly in the manufacturing sector. The size of the informal sector is estimated at 28-33% of Montenegro’s GDP and its share in total employment is estimated at over 20% (EC, 2019[23]).

Despite a notable rise in entrepreneurship over the past decade, firm growth is constrained by access to finance. Strict collateral requirements represent an important barrier for businesses. While the share of loans that require collateral is in line with the OECD average at around 60%, the level of collateral required – at 209% of the borrowed amount – is more than double the OECD average of 88%.3 The collateral requirements are particularly limiting for micro and small enterprises (MSMEs), which have limited assets. The banks’ preference for real estate collateral further compounds this challenge for MSMEs – see Access to finance (Dimension 3). The high collateral requirements reflect in part the lack of adequate information on creditors. However, progress has been made in this regard as coverage of the public credit registry in Montenegro has increased from 30.8% in 2018 to 41% in 2019, and information is regularly updated.4 Nevertheless, financing for start-ups and other higher risk ventures remains very limited.

Key sectors are being held back

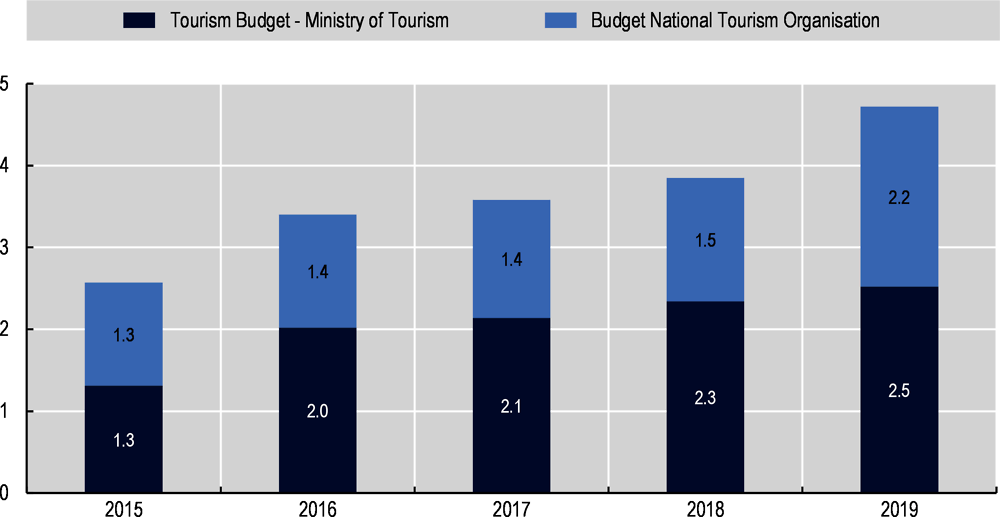

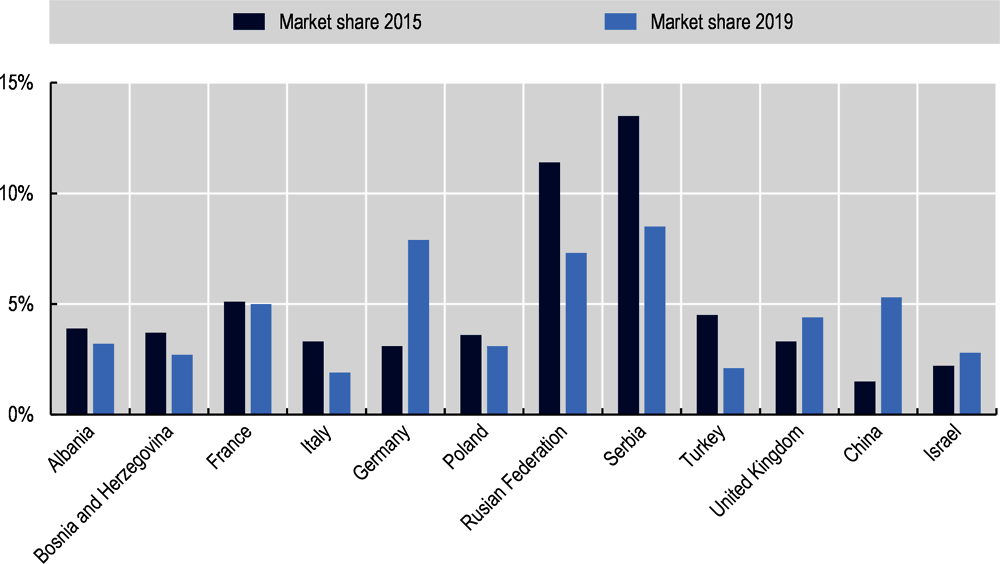

Tourism: The tourism sector is one of the most important sectors in Montenegro. In 2019, travel and tourism accounted for 32% of GDP and 33% of total employment (World Travel and Tourism Council, 2020[24]). However, the sector still suffers from high seasonality, which reduces employment and skills development as well as accessibility – see Tourism policy (Dimension 15). This undermines the quality of service, which is critical for developing the low-density high-end tourism compatible with Montenegro’s geographical and infrastructural constraints. The growth in high-end tourism is also constrained by inadequate waste management, poor water quality and uncontrolled development as these are all detrimental to the environmental as well as cultural heritage – see Environment policy (Dimension 13).

Agriculture: As a small and predominantly mountainous economy, Montenegro does not have a large agriculture sector. Even so, the sector contributes significantly to Montenegro’s goods exports and has significant potential for further growth. As noted in the introduction, the share of agriculture, forestry and fishing in GDP is small and has declined significantly over the past two decades, from 10.4% in 2001 to 6.4% in 2019. However, in 2018, agricultural products represented a relatively high portion (18.8%) of total exports.5 Agricultural productivity is undermined by high land fragmentation, lack of adequate infrastructure for irrigation, limited access to mechanisation and limited investment in R&D – see Agriculture policy (Dimension 14).

Information and communications technology (ICT): The ICT sector has considerable potential to boost Montenegro’s service exports and contribute to the development of the knowledge economy. Despite growth in recent years, the sector still faces significant challenges, especially the insufficient supply of skilled workers; their poor wage competitiveness (ICT sector wages are considerably higher in Montenegro than in other WB economies); underdeveloped collaboration between the sector and the relevant educational institutions; lack of access to finance, particularly for start-ups and high-risk venture capital; and weaknesses in the ICT infrastructure.6

A greener growth model would improve well-being

Air pollution: Air pollution is a significant concern in Montenegro, with the annual mean exposure to PM2.5 (particulate matter) reaching 21 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m3).7 This is twice the recommended limit of 10 µg/m3 set by the World Health Organisation (World Bank, 2017[25]) (WHO, 2018[26]). The main sources of pollution include steelmaking, agricultural processing, and the aluminium and tourism industries. Air pollution is further elevated in the winter months when domestic heating by solid fuels is added to the mix (IAMAT, 2020[27]).

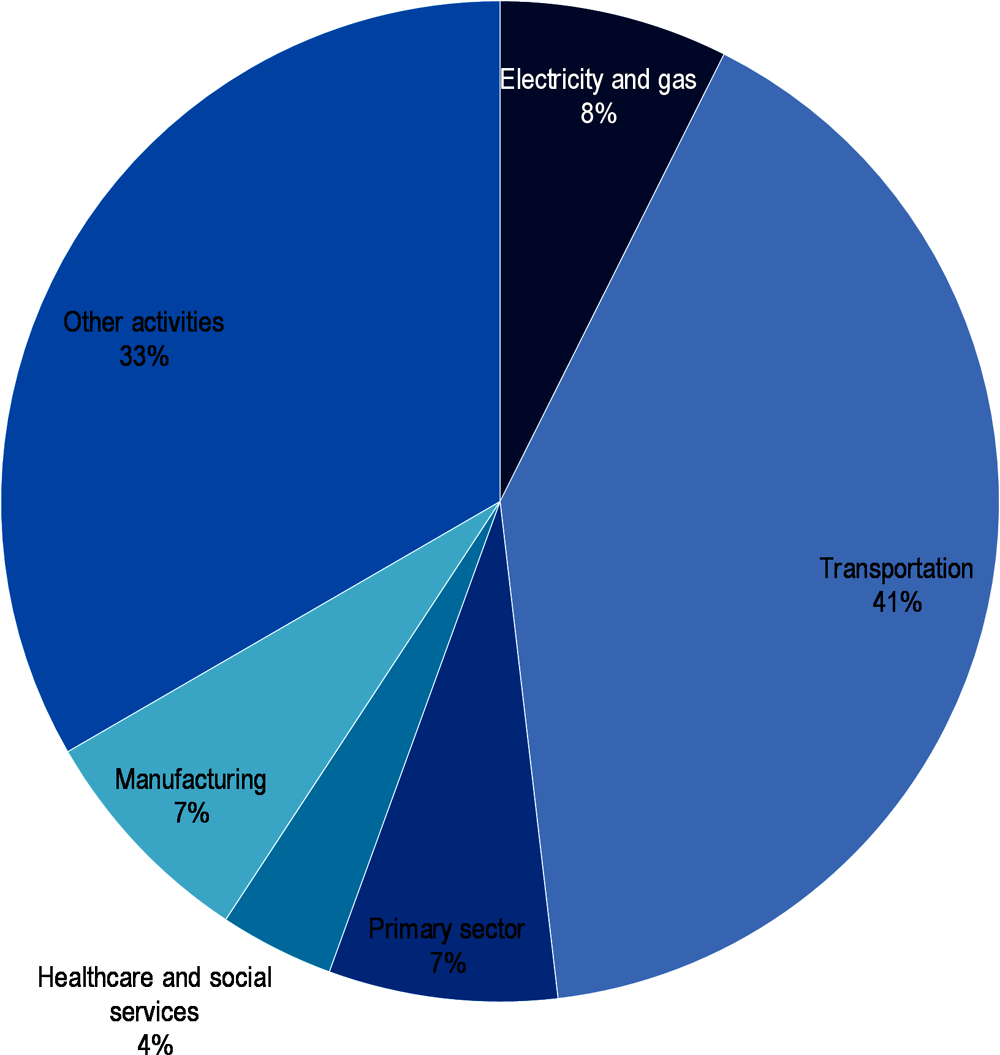

Climate change: Montenegro has made great progress in advancing climate change mitigation legislative and policy frameworks. Nevertheless, the economic output per unit of CO2 remains low (Environment Protection Agency, 2020[28]), and the highest emissions come from electricity and heat generation (61.4% in 2018, highlighting the fossil-fuel based energy production), and transport, which accounts for a little over 20% (Ministry of Sustainable Development and Tourism, 2020[29]). When it comes to climate change adaptation, a Disaster Risk Assessment was being prepared at the time of drafting and some flood risk management measures have been implemented, but more is needed to assess and adapt to the wide range of climate related risks going forward – see Environment policy (Dimension 13).

COVID-19 has exacerbated structural challenges

Montenegro was the Western Balkan economy hit hardest by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the second and third quarter (Q) of 2020, GDP declined by over 20% year on year (y-o-y), driven primarily by a sharp decline in exports (55.9% y-o-y in Q2, 70.1% y-o-y in Q3 of 2020), which reflected the loss of the summer tourism season as well as the decline in economic activity in major trading partners in the EU and the Western Balkan region. Weakening domestic demand compounded the impact of lost exports on the Montenegrin economy. Consumption fell by 5.4% in 2020, while annual investment contracted by 12.3%. As a result, annual GDP fell by 15.2% (Table 23.1) (EC, 2021[30]; EC, 2020[3]).

The crisis has exacerbated internal and external imbalances. The current account deficits have widened as exports contracted more strongly than imports – the current account deficit reached 26% of GDP at the end of 2020. Meanwhile, the negative impact on tax revenues, combined with higher government expenditures due to fiscal support and higher healthcare spending, resulted in a widening of the fiscal deficit to 11% of GDP in 2020. As a result, public debt rose to 105% of the GDP (EC, 2021[30]).

The labour market was strongly affected by the COVID-19 crisis despite the government’s measures to stave off some of the impact of the crisis. Since the start of the crisis, the government has introduced four packages of fiscal support for enterprises affected by the pandemic (Box 23.1). These packages have included measures such as wage subsidies for employees in affected companies, deferral of tax and social security payments, exemptions from payment of utility bills, moratoria on loan repayments and moratoria on enforcement of claims against enterprises in affected sectors. The government also created an Investment Development Fund to provide liquidity support to affected enterprises.8 The tourism and agriculture sectors were further supported by interest rate subsidies on new loans, and a reduction in the value-added tax (VAT) rate for the hospitality industry (from 21% to 7%). Despite these important measures, the effective loss of the tourism season – overnight stays declined by nearly 80% in January to November 2020 – resulted in a sharp increase in unemployment, from 15.4% in 2019 to 18.4% at the end of 2020, reversing a seven-year trend of steady improvement.

The impact on vulnerable households and poverty was mitigated by the government’s support measures. Financial assistance was provided to low-income pensioners and social welfare beneficiaries, and health and education workers received domestic travel vouchers. Additional support was provided to individuals who lost their jobs a result of the crisis through social security schemes and employment programmes. Vulnerable households were also supported through electricity subsidies from the state-owned power distribution company, which were doubled in the second package of economic measures.

As part of its responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, Montenegro carried out a number of tax measures, which included:

1. Payments of income taxes by individuals, companies and the self-employed were deferred in March 2020 for 90 days.

2. A one-off EUR 50 cash transfer was paid to beneficiaries of material assistance and of pension and disability insurance.

3. Loan repayments were deferred for a period of 90 days, at the request of individuals and companies, starting in March 2020.

4. A public loan scheme to improve the liquidity of the self-employed and companies impacted by the crisis. It allowed for a maximum amount of EUR 3 million per beneficiary. This scheme benefits from a simplified procedure, no approval fee and an interest rate of 1.5%.

5. Tax-debt repayments were made more flexible, including no interest for late payments of tax arrears.

6. A 60-day deferral of payment for customs duty and VAT was put in place in March 2020 for companies that could not continue their activity as a result of the crisis.

7. The reduced VAT rate (7%) was extended to certain catering and accommodation services.

8. Donations of medical goods to public entities were exempted from VAT.

Montenegro implemented a relatively wide set of responses to COVID-19 compared to other WB6 economies. For example, few WB6 economies implemented a public loan scheme, deferred loan repayments or offered direct cash transfers to households, which are centrepieces of Montenegro’s response to COVID-19. Montenegro’s comprehensive COVID-19 response package broadly aligns with those of OECD/G20 countries (OECD, 2020[31]).

Despite this support, many of the economy’s structural challenges have played a role in either amplifying the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic or limiting the scope of the policy responses to reduce its impact. The crisis has, therefore, provided important lessons on how to build more resilient economies and institutions:

Fiscal policy: The fiscal response has been important for reducing the economic fallout from the COVID-19 crisis, but has resulted in a significant deterioration in the fiscal position and an increase in public debt. In the context of weaker prospective revenues in the wake of the crisis, particularly if the recovery is slow, improving the efficiency of public spending will be critical over the coming months. It will also be vital to prioritise expenditures that can support the recovery and promote productivity growth and structural transformation for stronger and more resilient long-term growth. This includes increasing public investment, which has suffered significantly due to high and rising current expenditures. The crisis also highlighted the importance of rebuilding fiscal buffers in the post-crisis period. In addition to better management of expenditures this will also require tackling some of the structural constraints that undermine revenue performance and allow for more discretionary fiscal expenditures to counteract future shocks.

Innovation and technology adoption: The COVID-19 crisis has starkly demonstrated the importance of firm adaptability to meet new challenges and changing circumstances. The crisis has also revealed the advantages that firms which have embraced digitalisation and modern practices have over others. The resilience of the post-COVID recovery will therefore depend on the extent to which structural issues limiting firm innovation and technology adoption are addressed and to what extent digitalisation and digital skills become mainstreamed.

Access to finance: The crisis has highlighted the significance of a well-developed and diversified financial sector that can respond to the financing needs of enterprises – not only in times of crisis but also during the recovery phase. As in the rest of the region, the main instruments for providing additional liquidity to enterprises during the crisis came from the government through subsidised lending or lending guarantees. But a robust financial sector comprised of diversified financial institutions that can provide financing for riskier and innovative ventures – not just well-established enterprises with a long history of operation and significant assets – will be very important through the recovery phase and beyond.

Informality: The large size of the informal sector, and the significant share of informal employment even within the formal sector, have limited the scope of the measures aimed at protecting the income and employment of people in the most affected sectors. Informality is widespread in the sectors most affected by the crisis, including retail trade and tourism, and this segment has not been able to benefit from the government subsidies and other relief and support measures. Developing a more resilient economy will also depend on the extent to which incentives for formalisation can be enhanced and the oversight and sanctioning of non-compliance improved.

Health sector: Pre-existing poor health outcomes and inefficiencies in the health system have increased Montenegro’s vulnerability to COVID-19 and any future pandemics. This challenge is compounded by relatively low spending on health care (8.42% of GDP in 2018 compared to 12.6% in the OECD).9 Furthermore, health-sector revenues are highly sensitive to employment and economic downturns since they are financed largely by payroll contributions.10 Going forward, Montenegro will need to strengthen the resilience of its health sector through more funding; better pandemic preparedness, including training health workers; and increasing the supply of equipment by strengthening supply chains for essential medicines and other supplies, etc.

EU accession process

Montenegro began its EU accession journey in 2008 when it submitted its application for EU membership. The Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) came into force in September 2010 and Montenegro was granted EU candidate status in December 2010. Since then, Montenegro has advanced relatively rapidly along the accession path compared to most other Western Balkan economies. Accession negotiations began on 29 June 2012 and as of February 2021, Montenegro had opened 33 out of 35 negotiating chapters, 3 of which had been provisionally closed.

Further progress in the accession process and Montenegro’s eventual joining of the EU will strongly depend on adopting and aligning its legislation with the EU acquis, effective implementation of this legislation, and structural reforms that will enable the economy to meet the competitive pressures and other requirements of joining the EU bloc. The findings and recommendations published in this Competitiveness Outlook 2021 provide the monitoring and guidance needed for the government in meeting the requirements related to a number of critical chapters of the acquis when negotiating its accession to the EU. The Competitiveness Outlook also provides a good basis for assessing the critical challenges that the economy faces as a starting point for the development of the Economic Reform Programmes (Box 23.2).

Since 2015, all EU candidate countries and potential candidates prepare Economic Reform Programmes (ERPs) which play a key role in improving economic policy planning and steering reforms to sustain macroeconomic stability, boost competitiveness, and improve conditions for inclusive growth and job creation. The ERPs contain medium-term macroeconomic projections (including for GDP growth, inflation, trade balance and capital flows), budgetary plans for the next three years and a structural reform agenda.

The structural reform agenda includes reforms to boost competitiveness and improve conditions for inclusive growth and job creation in the following areas:

The structural reforms part of the ERPs is organised in two parts:

A first part identifies and analyses the three key challenges across those 13 areas. The identification and prioritisation of key challenges imply a clear political commitment at the highest level to address them and the ERPs should propose a relevant number of reform measures to decisively tackle each of them in the next three years.

A second part provides an analysis of the remaining areas (not included as key challenges) and may propose additional reforms to address them.

The European Commission and the European Central Bank then assess these programmes, which form the basis for a multilateral economic policy dialogue involving the enlargement economies, EU Member States, the Commission and the European Central Bank. The dialogue culminates in a high-level meeting during which participants adopt joint conclusions that include economy-specific policy guidance reflecting the most pressing economic reform needs. The findings of the Competitiveness Outlook provide guidance to the six Western Balkans EU candidates and potential candidates in identifying the key obstacles to competitiveness and economic growth, and in developing structural reform measures to overcome them.

Source: (European Commission, 2021[32]), Guidance for the Economic Reform Programmes 2022-2024 of the Western Balkans and Turkey, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/default/files/erp_2022-2024_guidance_note.pdf; (European Commission, 2018[33]), Economic Reform Programmes: Western Balkans and Turkey, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/20180417-erp-factsheet.pdf.

EU financial and development support

Montenegro has received considerable financial support from the EU, which has been its largest provider of financial assistance. Through the EU pre-accession funds, a total of EUR 506.2 million was allocated to Montenegro for the period 2007-20. The financing is aimed to assist the economy in improving its outcomes across the following areas: democracy and governance; rule of law and fundamental rights; environment and climate action; transport; competitiveness and innovation; education, employment and social policies; agriculture and rural development; and regional and territorial co-operation.

On 6 October 2020 the European Commission adopted the Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, which seeks to support the long-term economic recovery of the region, a green and digital transition and regional integration and convergence with the EU. The plan envisages the mobilisation of up to EUR 9 billion in investment in sustainable transport, human capital, competitiveness and inclusive growth.11

In addition to grant funding, the EU also provides important guarantees that support public and private investment by reducing the risks and costs associated with those investments. The new Western Balkans Guarantee Facility is expected to mobilise up to EUR 20 billion in investment over the coming decade.12

The Connectivity Agenda seeks to support investments in sustainable transport and clean energy. Set up under the Western Balkans Investment Framework, the latest package, which was presented at the Western Balkans Summit in Sofia on 10 November 2020, completes the delivery of the EU’s 2015 pledge to finance EUR 1 billion of investment to support better connectivity in the WB region. It also represents the first step in implementing the flagship projects under the Economic and Investment Plan for the region.

Process

Following the first two Competitiveness Outlook assessments, published in 2016 and 2018, the third Competitiveness Outlook assessment cycle for the WB6 economies was launched virtually (due to the COVID-19 pandemic) on 3 April 2020. The OECD team introduced Montenegro’s Competitiveness Outlook Government and Statistical Office Co-ordinators13 to the new digitalised assessment frameworks (see Assessment methodology and process chapter for details). The two primary documents for assessing each of the 16 policy dimensions – the qualitative questionnaire and statistical data sheet – were explained in depth, giving particular attention to new questions and indicators. The OECD team also explained digital solutions to be used to disseminate the material together with the detailed guidelines, tutorials and information on the assessment process, methodology and timeline.

Following the launch of the assessment, the Ministry of Economic Development disseminated the materials among all 16 Policy Dimension Co-ordinators and Statistical Office contact points in Montenegro. Where additional guidance was needed, the OECD team held teleconferences with Dimension Co-ordinators and Statistical Office contact points in April and May 2020.

All 16 Dimension Co-ordinators and Statistical Office contact points completed the assessment between April and May 2020. They assigned a score (see Scoring approach) to each qualitative indicator used to assess the policy dimension in question, accompanied by a justification. The completed assessments (qualitative questionnaires and statistical data sheets) were returned to the OECD team between May and July 2020.

The OECD reviewed the inputs and, where necessary, requested additional information from the Ministry of Economic Development, Policy Dimension Co-ordinators and Statistical Office contact points. The updated assessment materials were sent back to the OECD between July and September 2020. In addition, the OECD organised policy roundtable meetings between October and November 2020 to fill in any remaining data gaps, to get a better understanding of the policy landscape, and to collect additional information for indicators where necessary.

Based on the inputs received, the OECD compiled the initial key findings for each of the 16 policy dimensions. It then held consultations on these findings with local non-government stakeholders (including chambers of commerce, academia and NGOs) in November 2020. As a follow up, the OECD presented the preliminary findings, recommendations and scores to the Competitiveness Outlook Government Co-ordinator,14 Policy Dimension Co-ordinators and Statistical Office contact points at a virtual meeting on 17 December. The draft Competitiveness Outlook economy profile of Montenegro was made available to the Government of Montenegro for their review and feedback from mid-January to mid-February 2021.

Scoring approach

Each policy dimension and its constituent parts are assigned a numerical score ranging from 0 to 5 according to the level of policy development and implementation, so that performance can be compared across economies and over time. Level 0 is the weakest and Level 5 the strongest, indicating a level of development commensurate with OECD good practice (Table 23.3).

For further details on the Competitiveness Outlook methodology, as well as the changes in the last assessment cycle, please refer to the Assessment methodology and process chapter.

Exceptions

Unlike the other 15 policy dimensions, Competition policy (Dimension 5) is assessed using yes/no answers to 71 questions in a dedicated questionnaire. A “yes” response (coded as 1) indicates that a criterion has been adopted, whereas a “no” (coded as 0) indicates the criterion has not been adopted. The overall score reflects the number of criteria adopted. Moreover, some qualitative indicators which have been added to this edition of the assessment for the first time are not scored due to the recent character of the policy practice they capture and the unavailability of relevant data.

Introduction

Montenegro’s performance on the investment dimension has improved since the last assessment. The economy’s score has increased from 2.6 in the 2018 Competitiveness Outlook (OECD, 2018[34]) to 3.2 in the 2021 assessment, with notable progress having been made on all sub-dimensions. Although the economy has significantly improved its institutional framework by creating a new investment promotion agency, the Montenegro Investment Agency (MIA), with an extended mandate and capacities, the MIA has just started its work and the new scores for investment promotion and facilitation do not yet reflect these improvements. Montenegro ranks second amongst the WB6 economies for economic performance. While Montenegro is among the top WB6 performers for its investment policy, its investment promotion and facilitation performance still lags behind its neighbours (Table 23.4).

State of play and key developments

Montenegro is the leading WB6 economy for attracting FDI. Net FDI inflows have averaged USD 487 million a year over the last five years (Figure 23.2). In 2019, the economy’s net FDI inflows accounted for 8.4% of GDP. This figure is higher than neighbouring economies: 8.3% for Serbia, 7.8% for Albania, 3.8% for Kosovo and North Macedonia, and 1.9% for Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is also higher than the average for upper-middle income economies (1.6%) and OECD economies (1.5%).

FDI in Montenegro is mostly concentrated in the tourism, energy, telecommunications, banking and construction sectors. Its origins are diverse, with no single economy dominating. The most significant investments have originated from Hungary, Italy, Russia and Serbia, with new interest coming from Azerbaijan, China, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and the United States.

Sub-dimension 1.1: Investment policy framework

Overall, Montenegro has a clear and comprehensive legal framework for investment activities and conducting business. The main law governing investment activities is the Foreign Investment Law (FIL), adopted in 2014. The FIL provides investors with national treatment, makes no restrictions in terms of investment activities, foreign companies can own 100% of a domestic company, and profits and dividends can be repatriated without limitations or restrictions. Montenegro has enacted sectoral and business-related laws15 outlining guarantees and safeguards for investors in accordance with EU standards. Recent positive developments reinforcing the investment framework include the adoption of a public-private partnership law as well a public procurement law at the end of 2019.

The government is endeavouring to ensure that the regulatory framework for investment is consistent, clear, transparent, readily accessible and does not impose undue burdens. In May 2019, the government adopted the Individual Reform Action Plan for implementing the Regional Investment Reform Agenda at the national level (IRAP), which represents a set of concrete reform actions in three areas of investment policy: investment entry and establishment, investment protection and retention, and investment attraction and promotion, all of which were completed in December 2020. The IRAP was adopted within the framework of the Investment Pillar of the Multi Annual Plan for Regional Economic Area (MAP REA) to continue the implementation of the commitments outlined under the investment pillar of the MAP REA 2017-2021. These efforts will continue through the Common Regional Market Plan 2012-2024.

The Ministry of Economy publishes the most important legislation concerning trade and investments on its website.16 The development of laws, treaties and regulations involves stakeholder consultations and includes relevant ministries and other public bodies. Public participation in policy making and implementation is secured through the relevant decrees.17 Nevertheless, NGOs – including business associations – have complained about recent policy-making and legislative processes that lacked public consultation and involvement of key stakeholders (EC, 2020[35]).

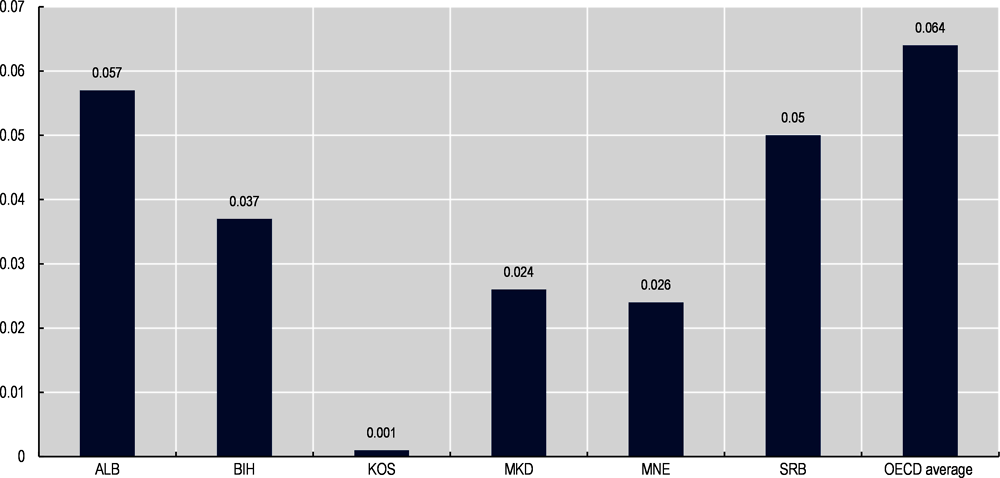

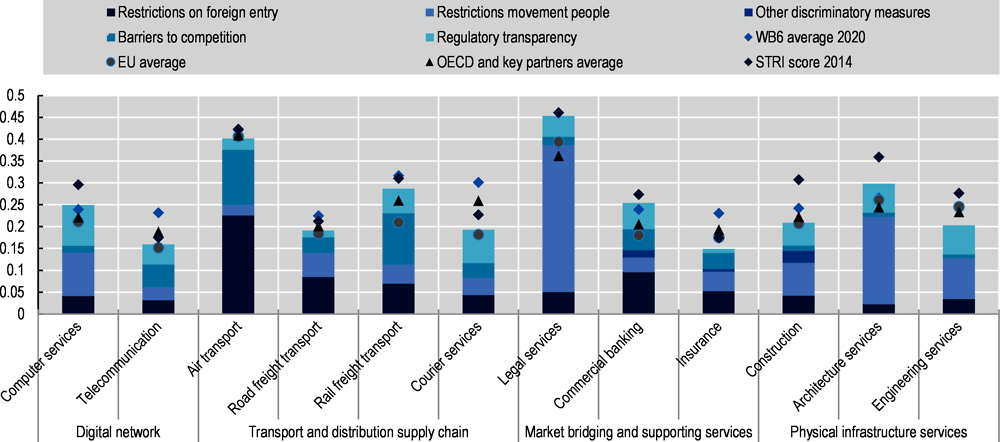

In Montenegro, the market is open and exceptions to national treatment are very limited. The economy’s score in the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index (Figure 23.3),18 which assesses and benchmarks market access and exceptions to national treatment, was 0.03 in 2018. This indicates that the economy maintains only a handful of restrictions (notably in the transport sector), making its FDI regime less restrictive than the average OECD economy (0.064) (World Bank, 2020[36]). This suggests that foreign investment rules do not constitute impediments to FDI. However, the economy does not have a negative list indicating the sectors where foreign investment is prohibited or conditioned and outlining which discriminatory conditions apply.

Investor protection against expropriation without fair compensation is enshrined in the constitution and its modalities are defined in the Law on Expropriation. The law stipulates that expropriation measures are taken only in a non-discriminatory manner, for a public purpose, under due process of law, and with fair compensation. It does not however recognise the concept of indirect expropriation. The expropriation law clearly defines the procedures for calculating compensation fees, including that the expropriation fee is determined by a commission of five members, at least three of whom are forensic experts in the relevant profession.

Administrative-judicial protection from expropriation decisions is available for dissatisfied parties; it also determines the fee for expropriation. Thus, a party can file an appeal against an expropriation decision with the Ministry of Finance. If the party is not satisfied with the decision of the Ministry of Finance, it can initiate an administrative dispute against it in the Administrative Court of Montenegro. Dissatisfied parties also have the opportunity to initiate civil proceedings in regular courts.

Montenegro has signed a large number of bilateral investment treaties (BITs),19 which constitute an additional layer of protection for foreign investors. The Government of Montenegro is currently in the process of reforming its existing network of BITs and defining a new BIT model that will balance investor protection provisions and national strategic interests, while fully complying with EU standards and good international practices.

Foreign investors have the same rights and remedies under the national court system as domestic investors when it comes to dispute settlement. The justice system is continuing its reform efforts under the 2019-2022 judicial reform strategy,20 which focuses notably on the independence, efficiency and professionalisation of the judiciary. Overall, the judiciary system is independent but remains vulnerable to political interference. Its financial resources have been slowly but steadily increasing over 2016-2020 to reach EUR 39.1 million (EC, 2020[35]). However, according to similar EU reports, it remains lower than the judiciary budgets of other WB6 economies. Overall, the court system is functioning well, and investors can generally rely on it for a wide range of disputes. Montenegro has commercial courts which have first-instance jurisdiction in commercial matters. Judges are trained to hear complex commercial disputes and the backlog of cases is decreasing. Though the disposition time (the average time from filing to decision) for commercial cases increased from 107 days in 2018 to 116 days in 2019, it remains comparable to OECD economies.

Montenegro is stepping up its efforts to offer alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. It ratified the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (ICSID Convention) in 2012 and the 1958 Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (New York Convention) in 2006. By virtue of their adherence to the New York Convention, foreign arbitral awards are recognised. Moreover, Montenegro signed the United Nations Singapore Convention on Mediation in 2019.

Montenegro also adopted the Arbitration Act in 2015 and is in the process of adopting the Law on Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR),21 which provides for compulsory recourse to ADR mechanisms for specific types of cases. According to the European Commission, Montenegro is recording a positive trend in alternative dispute resolution for which a programme and accompanying action plan for 2019-21 were adopted at the end of 2018. In 2019, 917 cases were referred for mediation, up from 629 cases in 2018 and 437 in 2017, while 403 cases were resolved through mediation in 2019, compared to 107 in 2018 (EC, 2020[35]).

Montenegro has sound intellectual property (IP) rights laws, which are harmonised with EU legislation and contain the minimum requirements of the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). Montenegro is a member of the World Intellectual Property Organization and adheres to the main international treaties and conventions on IP rights. The Ministry of Economic Development of Montenegro is the public authority in charge of registration, protection and enforcement of IP rights, and co-ordinates closely with other IP institutions, including customs. Since 2018, following a restructuring of the administration, the IP office is part of the Ministry of Economy. It should be noted that following these changes, the staffing of the office was reduced.

Montenegro is strengthening its IPR enforcement and implementation. It has reinforced the capacity of the intellectual property rights co-ordination team and the attached working group through regular training. The Ministry of Economic Development has strengthened its co-ordination with other IP-related institutions and boosted its efforts to sensitise businesses and the public and provide them with better access to information on IP rights. The Commercial Court of Montenegro, as a specialised court, has the exclusive jurisdiction for resolving disputes in the field of intellectual property. The Commercial Court has a Department for Disputes on the Protection of Copyright and Intellectual Property Rights, which has ten judges who are regularly trained professionally in this area.

The government has also reinforced its IP rights awareness raising and access to information. The Ministry of Economic Development has initiated measures such as seminars and campaigns to proactively raise awareness on IP, as well as capacity-building programmes on how to file for IP protection. In addition, relevant information about registered IP rights is available on the ministry’s website,22 as are patent registers and other databases on IP rights.

Sub-dimension 1.2: Investment promotion and facilitation

Montenegro is currently modernising its investment promotion agency structure and strategy. The last Competitiveness Outlook reported that the Montenegrin Investment Promotion Agency (MIPA) was constantly short-staffed, had limited capacities and a mandate focused solely on investment promotion. Following the adoption of the new PPP law in October 2019, MIPA and the Secretariat for Development Projects have ceased to exist and the Montenegro Investment Agency (MIA) was established in 2020 with significantly more employees and a much broader set of responsibilities. By the end of 2020, the MIA had 27 employees compared to the 5 previously employed by MIPA. According to the organisation’s Personnel Plan, it seeks to increase the total number of employees to 42 by 2021.

The establishment of the MIA is expected to reinforce Montenegro’s investment facilitation services and activities. It has recently been put in charge of revamping administrative systems to speed up procedures and provide the conditions for efficient work, which requires close co-operation between the agency and relevant ministries. While the former agency MIPA was not involved in any business registration procedures, the MIA provides investors with information on all the necessary steps for business registration, as well as on which institutions to reach out to in the process. The Government of Montenegro has also approved an action plan aimed at helping businesses by digitalising and cutting unnecessary procedures, including for company registrations, and establishing an e-cadastre.

Key recent progress on simplifying company registration include:

Developing two rulebooks23 which clarify the registration procedure, the single registration application of economic entities, and the content and manner of keeping the Central Registry of Economic Entities.

Merging the 16 previous forms for registering a business into a single form, and progressing on electronic company registration through eFirma.

Cutting various registration fees: for example the fee for establishing a joint stock company has been reduced from EUR 50 to EUR 40, and the minimum capital for electronic registration of a one-member limited liability company for resident founders has been reduced to EUR 1.

Following its establishment, the MIA has started developing investor targeting actions. It is trying to move from MIPA’s reactive stance to a more proactive targeting of potential investors and countries. For instance, in 2020 the MIA embarked on an investor outreach campaign for the furniture manufacturing sector with financial and technical assistance from the World Bank. It has also defined target countries and started organising missions.

Montenegro has put a complex and multi-layered investor incentive scheme in place to attract investment. Incentives are provided by the state and include 1) subsidies (mostly through the Program for Improving Competitiveness, consisting of 10 programme lines to provide financial and non-financial support to potential and existing entrepreneurs, SMEs and large enterprises, as well as clusters); 2) tax relief (write-offs, deferrals of taxes and contributions); 3) loans with lower interest rates (through the Investment Development Fund's loans); and 4) guarantees. In addition, incentives and facilitation measures are provided to investors in Free Zones and Business Zones or by the Law for Specific Projects, while other incentives are provided by municipalities and for investing in least developed areas, primarily in the north (OECD, 2017[38]). However, the system could prove difficult to navigate for foreign investors due to lack of awareness and clarity on qualifications (EC, 2020[35]). On the control side, the government ensures the transparency of state aid in the annual report on granted state aid by the Agency for Protection of Competition, which is publicly available on its website.

The establishment of the MIA is also a positive step towards improving aftercare services, which requires strong co-operation with other institutions and regulatory bodies. Although the agency does not have a formal mandate to provide aftercare services, it still answers investors’ enquiries on an ad hoc basis.

Sub-dimension 1.3: Investment for green growth

Overall, Montenegro has started to develop a sound green investment policy and promotion strategy. Its national strategy, the Smart Specialisation Strategy of Montenegro (S3.me) 2019-2024, based on the EU’s cohesion policy, promotes green growth and building a legal framework that encourages green investment (Ministry of Science of Montenegro, 2019[39]). This strategy paves the way for future green investment programmes as it defines the priorities and focal areas to be developed for sustainable and green growth. In addition, Montenegro has adopted two very key laws regulating green investments and innovation: the new Law on Innovation Activity and the Law on Incentives for the Development of Research and Innovation. These are accompanied by an implementing body, the Innovation Council, and an innovation fund that supports targeted projects.

Montenegro respects core investment principles such as investor protection, intellectual property rights protection and non-discrimination in areas inclined to attract green investment. In addition, the government has developed policies, laws, market-based instruments and regulations in the energy sector to encourage private investment for green growth, while including sustainable development provisions in the new BIT model. Additional measures are also adopted at the local level to encourage private green initiatives. Several programmes have been developed with international organisations for achieving green investment, notably the Growing Green Business in Montenegro 2018-2021 project developed in co-operation with the United Nations Development Program (UNDP).

Montenegro has also developed a strong framework for choosing public and private partnerships for green growth. It has recently adopted a favourable regulatory framework through the new Law on Public-Private Partnerships in 2019 that reinforces its ability to mobilise and scale-up green investments by leveraging domestic and international public and private investments in large-scale projects, including infrastructure. The new PPP law was developed in co-operation with donors following good international practices. It includes financial sustainability, value for money and environmental performance as key elements of feasibility studies of proposed PPP projects. In addition, a risk-sharing principle is clearly stated in the PPP law. Finally, the new MIA will be in charge of facilitating, promoting and monitoring PPP projects, including those for green investment.

The way forward for investment policy

Over the past decade, Montenegro has developed a solid track record in attracting and promoting investment, building on its openness and business-friendly environment. It has initiated important reforms, notably the establishment of a new institutional framework for investment promotion. It could further these efforts and remain an attractive investment destination through the following actions:

Improve the transparency and inclusiveness of policy making. More open and inclusive policy-making processes help to ensure that policies will better match the needs and expectations of citizens and businesses. Improving the public consultation process and including foreign investors would lead to better targeted and more effective policies.

Continue efforts aimed at encouraging the use of alternative dispute mechanisms. These mechanisms can help alleviate the pressure on the judiciary system, build trust and create a more business-friendly environment for conflict resolution. Conducting awareness-raising campaigns to increase the use of alternative dispute mechanisms will reassure prospective investors that fair resolution processes exist in the event of commercial disputes.

Accelerate the establishment of the MIA, clarify its aftercare mandate, and reinforce its capacity and resources in order to improve its investment facilitation and aftercare services. Increased resources would help streamline the large mandate of MIA, while greater inter-institutional co-ordination would avoid repetitive and overlapping objectives. In addition, the government needs to clearly define the MIA’s responsibilities for aftercare services, notably by expanding the agency’s mandate and producing a clear system for enquiries.

Streamline the multiple investment incentives and reinforce mechanisms for evaluating their cost and benefits, their appropriate duration, and their transparency. The government should increase the clarity and awareness of these incentives through greater transparency on their qualification criteria and by targeting foreign investors through awareness-raising campaigns.

Further reinforce the MIA’s green investment promotion activities. Montenegro should systematically consult with the private sector and other local stakeholders in the design and implementation of strategies and plans, policies and regulations that are relevant for green investment.

Introduction

Montenegro’s performance on the trade policy dimension has improved since the last assessment. The economy’s score has increased from 2.6 in the 2018 Competitiveness Outlook to 3.2 in the 2021 assessment (Figure 23.1), with notable progress on all sub-dimensions. Montenegro has improved inter-ministerial consultations on trade policy by establishing new bodies and adopting cross-sectoral strategies, including for implementing its WTO commitments. In addition, the economy has improved its regulatory framework for implementing public consultation standards through a new decree on state administration,24 which aims to systematise the public consultation process and promote stakeholder participation in trade policy design.

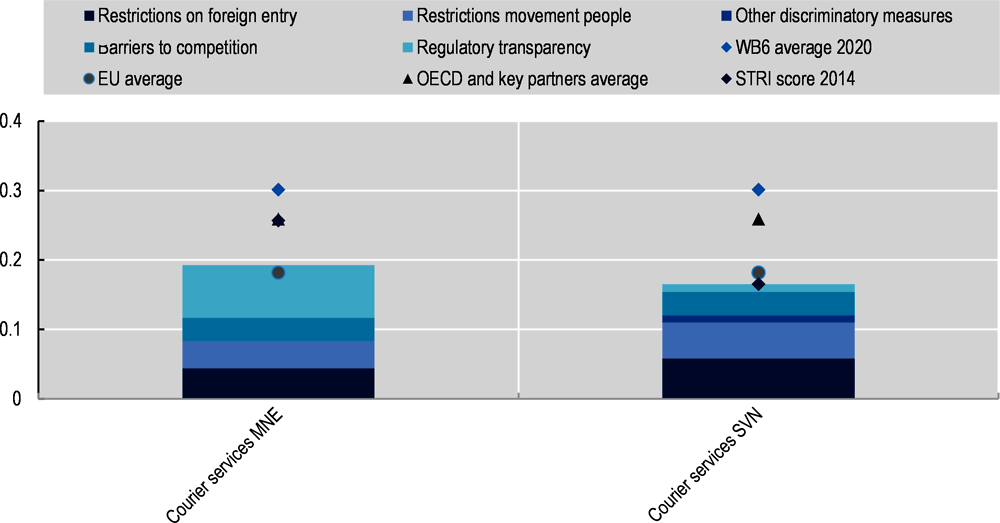

As regards trade in services, Montenegro has put in place policies to liberalise its services markets. As a result, significant progress has been made in lowering non-tariff barriers that were restricting services. Efforts have been primarily regional, with the conclusion of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) Additional Protocol 6 in December 2019 and its ratification in June 2021. Montenegro continues to improve its trade policies. Some nodes still exist. The economy could focus on lifting and modifying some economy-wide restrictive measures affecting foreign entities from third countries wishing to invest and operate in Montenegro. The context of the COVID-19 pandemic has undermined the efforts of many states to lower barriers to trade. However, Montenegro is one of the few economies not to have introduced trade restrictions. This is particularly important in a context where recent OECD studies of member economies tend to show a growth in the number of trade-restricting regulations in 2020 (OECD, 2021[40]).

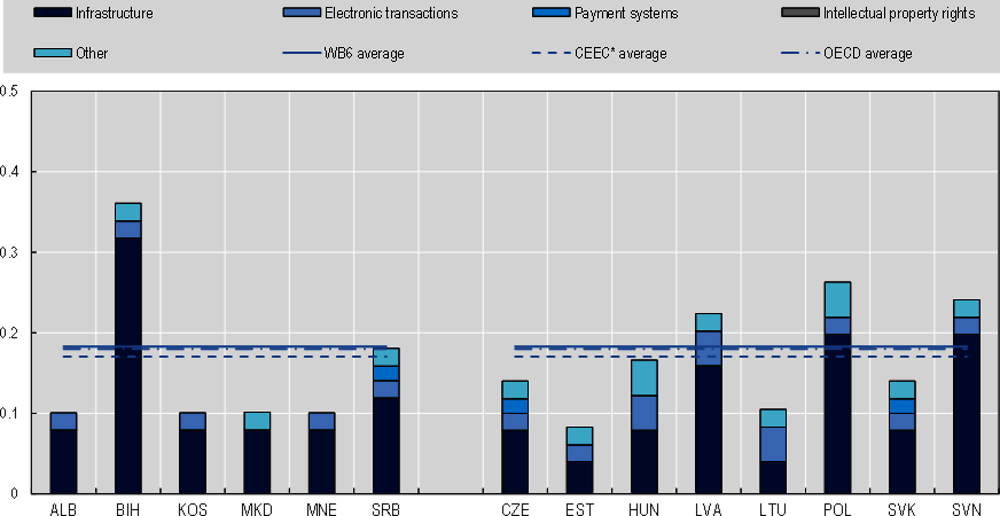

Finally, Montenegro is the regional leader in e-commerce trade flows in terms of increase in business-to-consumer (B2C) sites and trade flows made through the Internet, with a very low degree of trade restrictions in digitally enabled services. However, there have been no substantial changes to the e-commerce policy framework since 2018. Implementation efforts have not evolved fast enough, co-ordination mechanisms are absent and programme planning is insufficient, leading to inadequate monitoring and evaluation processes. These explain its below-average score on this sub-dimension (Table 23.5).

State of play and key developments

Montenegro’s exports of goods and services have been growing steadily since 2015, though this growth has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Foreign trade overall increased from 105.6% of GDP in 2017 to 108.5% in 2019 (in real terms), compared with 103% in 2015. In 2019, Montenegro’s exports of goods and services represented 43.7% of GDP, while imports of goods and services were 64.8%.25

Exports of goods reached EUR 465.6 million in 2019, while imports reached EUR 2.5 billion. The external deficit in trade in goods and services accounted for 21.1% of GDP in 2019. Montenegro is a net exporter of commercial services, with commercial exports accounting for EUR 1.7 billion against EUR 677.6 million in imports.

Serbia is Montenegro’s main trading partner, accounting for 23.6% of total exports in 2018, followed by Hungary (11.7%) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (7.8%). Montenegro's main supplier is also Serbia, with 19.3% of Montenegro's imports coming from Serbia, followed by China and Germany (10.1% and 9.2% respectively). As for the European Union, it accounted for 44% of Montenegro's exports and 48.5% of its imports in 2018.

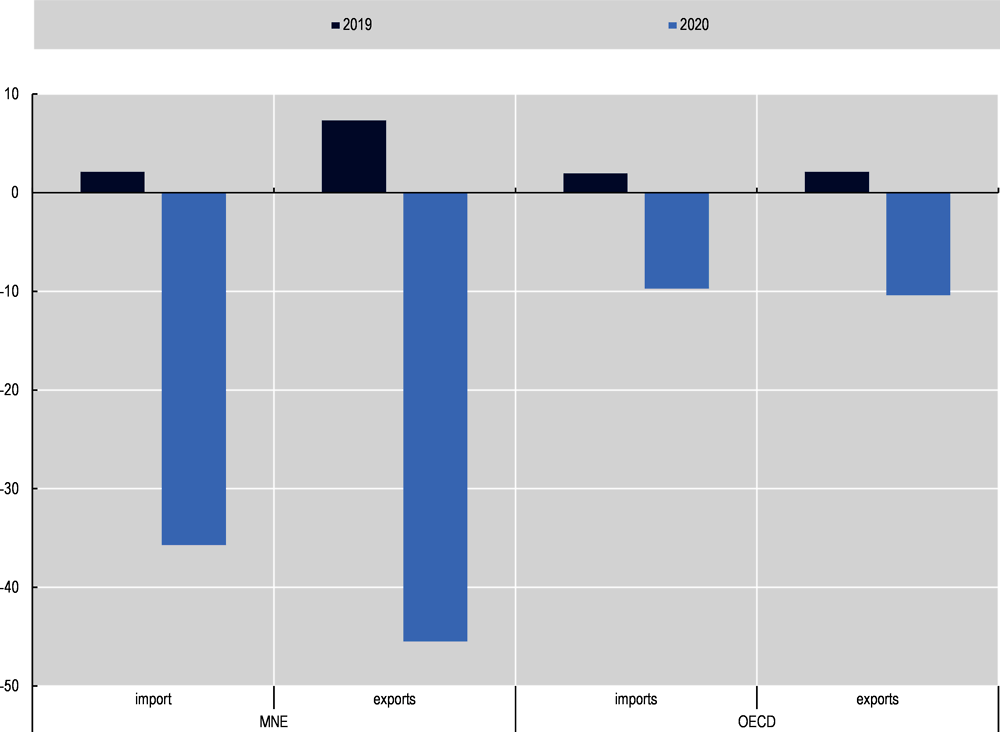

Like all economies, Montenegro has been heavily affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic-related export bans, restrictions on the movement of people and closures of shops and services led to a significant decline in imports and exports in Q2-Q3 2020 compared to 2019 (imports down 35% and exports 45%; Figure 23.4).

The tourism sector, which accounts for 25% of the economy’s GDP, is expected to contract by 12.4% in 2020. The tourism and travel industry has been hit hard by the movement-of-people restrictions imposed to limit the spread of COVID-19. The decrease in tourism has also affected other related industries, such as food, entertainment and retail, as well as tourism-related investment – see also Tourism policy (Dimension 15). In 2020, Montenegro’s current account deficit (CAD) is projected to increase to 16.8% of GDP, making it the largest in the WB6 region (World Bank, 2019[43]).

The closure of EU borders to non-EU citizens, as well as other regulatory responses in the Western Balkans, have particularly affected freight transport services. The Western Balkan economies set up the CEFTA co-ordinating body to exchange information on trade in goods at the beginning of the pandemic. They also set up priority "green lanes" with the EU and “green corridors” within the WB6 to facilitate the free movement of essential goods through priority "green" border/customs crossings (within the WB6 and with the EU). At the peak of the crisis (April to May 2020), most road transport in WB6 economies passed through these green lanes and corridors, and they have helped to maintain a certain degree of international trade in goods in the region. Only about 20% of the goods that benefited from the green corridor regime (i.e. within the WB6) were basic necessities, the rest being regular trade. Such inclusive regional co-operation has proven very efficient in mitigating the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and is helping economies to recover.

Sub-dimension 2.1: Trade policy framework

A fundamental principle of regulatory transparency is that the regulatory development process is open to all relevant stakeholders through formal and informal consultations before and after adoption. These co-ordination and consultation mechanisms have a positive impact on the efficiency of economic activities and the level of market openness, as they can improve the quality and enforceability of regulations (OECD, 2019[44]). In addition to laws setting out consultation obligations, governments are also adopting secondary standards such as guidelines to better systematise the public-private consultation (PPC) process. These include clear and detailed directives for conducting the process in a consistent manner regardless of the institution carrying out the PPC.

Montenegro has a robust regulatory framework for institutional co-ordination on trade policy formulation. The Ministry of Economic Development, the main ministry in charge of designing trade policies, regularly involves other ministries26 in the development of trade regulations at all stages of the policy-making process.

Progress has been made since the previous cycle of analysis, with new platforms for inter-institutional co-ordination being established in 2018. These include the Government Working Group for Trade Policy Review process (TRP),27 and increased competencies for the National Trade Facilitation Committee (NTFC)28 with the adoption of a new strategy for trade facilitation for 2018-2022.29 These developments have allowed the Ministry of Economic Development to consult on trade with an increased number of agencies and institutions (e.g. ministries of economics, agriculture, infrastructure, industry, customs authority, national standardisation body).

Progress has been made on the regulatory framework for public-private consultation (PPC) standards. The new Decree on State Administration (2018)30 introduces a mandatory consultation procedure in which the government must hold a public hearing when preparing laws and strategies. This is obligatory unless the changes concern “extraordinary, urgent or unpredictable circumstances”.31 The use of simplified legislative procedures (thus bypassing the consultation process) that affect the business community is a real challenge in the region (OECD, 2019[44]). Montenegro has made efforts to address this problem and to subject the majority of its regulations, particularly those related to trade, to a normal legislative process. This positive trend was already apparent in the previous assessment cycle; around 10% of all laws in 2016-2018 were adopted without PPC (Montenegro Ministry of Public Administration, Digital Society and Media, 2020[45]) In addition, it is now mandatory for the government to invite those stakeholders it deems relevant to provide inputs and comment on draft laws.32 The Decree on State Administration has also extended the scope of public consultations to include national strategies. An online participation platform has also been created to facilitate public consultations.33 Following the consultations, the ministry responsible for the draft regulation publishes a report on the consultation process on its website and the e-government portal, and disseminates it to the entities that participated in the process.34

As far as monitoring is concerned, regulatory impact analysis (RIA) was formally introduced in 2012 and enhanced further in 2018. A mandatory RIA report must accompany each legislative proposal submitted to the government for approval. Montenegro has a well-developed procedure for RIA, and the Ministry of Finance – as the central RIA unit in Montenegro – conducts the evaluation process efficiently. Since the last assessment cycle, RIAs have been systematically produced, though their quality could be improved further. They do not always compare several policy options and lack other important elements, such as assessments of impacts on the stakeholders most affected. Their publication also has room for improvement. Only 51% of them, according to the most recent report available, were published within the deadlines imposed by the law.

The Ministry of Public Administration, Digital Society and Media produces statistics on the number of legislative projects that have been subject to PPCs; reports for 2018 and 2019 are available. The reports are comprehensive and detailed but still published on an ad hoc basis. There is an upward trend in the participation by interested members of public in the policy-making process, with an increase in the number of comments received compared to 2018. In addition, there is also a notable trend in the number of comments accepted. For comparison, in 2019 the percentage of accepted comments out of the total number of comments received was 77%, in contrast to 2018 when the percentage of accepted comments out of the total number of comments received was 51% (Montenegro Ministry of Public Administration, Digital Society and Media, 2020[45]).