3. First-tier benefits

Slovenia has a low level of income inequality in old age and is close to the OECD averages regarding relative poverty and material deprivation for older people. Old-age poverty is particularly concentrated among older people living alone. The levels of both the minimum pension and safety-net benefits for older people are relatively high in international comparison, although the coverage rate of the safety net is low. This is likely a result of the obligation of family members to provide support. The old-age safety net and the pension scheme are not sufficiently co-ordinated, with safety-net eligibility thresholds currently exceeding the minimum pension after a full career and with differing eligibility ages for women. Moreover, part of the old-age safety-net benefits is only available to people who are not in paid work, which discourages eligible people from engaging in formal employment.

First-tier benefits provide older people with basic income security with the aim of ensuring that elementary needs are fulfilled. There are three types of first-tier benefits:

Basic pensions are pension schemes in which the benefit is not tied to previous earnings. Entitlement to a basic pension is either non-contributory based on years of residence or contributory based on years of contributions, irrespective of the level of contributions paid.

Minimum pensions refer to the minimum of a specific earnings-related pension scheme or of all schemes combined, to which people become eligible if they reach a certain amount of years of contributions. People who have built up an earnings-related pension that is below the minimum pension level, and fulfil the qualification requirements for the minimum pension, are provided a top-up to the level of the minimum pension.

Social assistance or safety-net benefits are means-tested benefits that provide an income top-up to those who do not have sufficient pension entitlements to fulfil basic needs.

Slovenian first-tier benefits consist of a combination of protection mechanisms in the contributory earnings-related pension scheme and social assistance benefits. Within the contributory scheme, the minimum and guaranteed pensions provide income floors that increase with the length of the contribution period from at least 15 years. Women older than 63 years and men older than 65 who have insufficient means to fulfil basic needs can claim financial social assistance and supplementary allowance. Access to social assistance benefits is restricted by a means test and only available to people who cannot receive support from their partner or children, but the benefit levels are higher than those provided by minimum and, until 2021, guaranteed pensions under the contributory pension scheme.

This chapter consists of three parts. The first part gives an overview of old-age inequality and poverty in Slovenia relative to other OECD countries. It highlights some social groups that are more vulnerable in old age. In the second part, Slovenian safety-net benefits, including financial social assistance and supplementary allowance, are discussed and compared to non-contributory benefits in other OECD countries. Finally, Slovenian minimum pension provisions and their interaction with safety-net benefits are analysed relative to contributory benefits in other OECD countries and to other social and labour market income measures in Slovenia.

3.2.1. Low income inequality

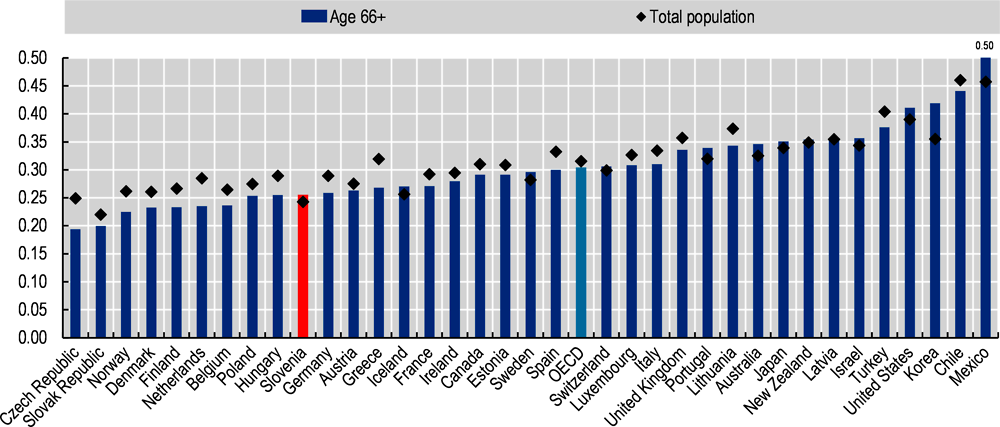

With a Gini coefficient – a measure of inequality that equals 0 if every person receives the same income and 1 if one person receives all income – of 0.256 among the population aged 66 and over, old-age income inequality in Slovenia is substantially below the OECD average of 0.304 (Figure 3.1). The Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic have the lowest levels of old-age income inequality, with a Gini coefficient just below 0.200. The Slovenian level is comparable to that of Germany, Hungary and Poland.

Low income inequality among older people in Slovenia is the result of the compressed wage distribution both before the transformation of the economy in the 1990s and, to a lesser extent, due to a high degree of wage co-ordination at the sectoral level since the transformation (OECD, 2020[1]). Moreover, the important role played by minimum pensions, as discussed in greater detail later, further reduces income inequality after retirement.

Over 2004-17, old-age income inequality was stable in Slovenia, as in the OECD on average (Figure 3.2). The Gini coefficient among older people increased by more than 0.05 in Latvia, Lithuania and Luxembourg, whereas it decreased by more than 0.05 in Greece and Israel.

3.2.2. Old-age poverty

Relative poverty among older people is just below the OECD average (Figure 3.3). More precisely, measured as having a disposable income below half of the median equivalised household income, 13.2% of people aged 66+ fall below the relative poverty threshold in Slovenia, compared to 14.1% in the OECD on average. The relative poverty rate is higher at 17.2% among the 76+ in Slovenia, similar to the OECD average of 16.6% and substantially higher than among the 66-75 age group, which stands at 10.5%.

The depth of poverty, which measures how much the average disposable income of the poor is below the relative poverty threshold (in percentage of the threshold), is slightly lower in Slovenia than in the OECD on average (Figure 3.4). Older people classified as poor based on the relative poverty line defined at 50% of median income have on average a disposable income that is 17% below the threshold against 23% in the OECD on average.

The poverty depth among people aged 66+ is lower than in Slovenia in about one-third of OECD countries, including the Nordic countries, Canada, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Ireland, New Zealand and the Slovak Republic. As in most countries, the depth of poverty is lower among older people than among the whole population for whom the average disposable income of people in poverty is 22% below the poverty threshold. Only Finland has a lower depth of poverty in the total population than Slovenia.

The relative old-age poverty rate declined by 3.3 percentage points between 2004 and 2017 in Slovenia, while it remained stable for the OECD on average (Figure 3.5). The reduction in old-age poverty was larger than 5 percentage points in Australia, Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, while the three Baltic countries saw a dramatic increase of at least 15 percentage points. At the same time, the poverty rate in the Slovenian working-age population (26 to 65 years) increased by 1.5 percentage points, thereby reducing the poverty gap between working-age and older people over this period.

Slovenia has comparatively high levels of material deprivation among older people. Of all people aged 65+, 11.6% cannot afford at least three items of a nine-item list (Figure 3.6). That is just above the EU-27 average of 11.3%, and higher than the rate in the majority of European OECD countries. Thus, Slovenian old-age poverty rates are average not only in relative but also in absolute terms, with more than one in ten older Slovenians not being able to afford several basic goods. In Slovenia, material deprivation affects older people more than working-age individuals, as in the Baltic countries, Poland and the Slovak Republic. While the depth of income poverty indicates a rather high concentration of people just below the relative poverty threshold, the material deprivation rate signals that the income of a large share of these people remains insufficient to fulfil their basic material needs.

3.2.3. Older women face large vulnerabilities

Material deprivation in Slovenia has been declining for both older people and people of working age since 2013, and even since 2007 among older women. Whereas material deprivation was continuously at a similar level for men and women of working age between 2004 and 2018, there was a significant gender gap among older people throughout this period to the detriment of women (Figure 3.7). In 2019, 13.5% of women aged 65+ could not afford at least three items from a nine-item list, compared to 9.2% of older men and 8.3% of people of working age.

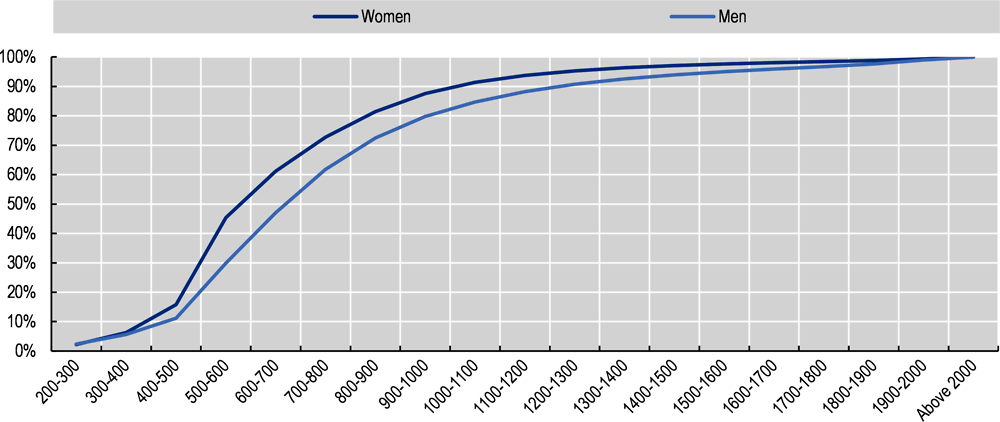

The gender gap in old-age income poverty rates is large in Slovenia, the fifth largest in the OECD after the three Baltic countries and Korea (Figure 3.8). Of all Slovenian women aged 66+, 17.8% have an income below half the median income, compared to the OECD average of 16.6%, against 8.4% and 10.9% for men, respectively. The share of older women below the relative poverty threshold is thus double the share of men in Slovenia. In particular, old-age poverty among women is higher than in Slovenia’s regional peers including Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy and the Slovak Republic. Women are overrepresented among pensioners receiving low pension benefits, likely due to their somewhat lower labour market participation rates both before (Vodopivec and Hribar-Milic, 1993[2]) and since the 1990s (OECD, 2021[3]). As such, their higher likelihood of living alone due to outliving their partners makes them more prone to falling below the poverty threshold because of higher individual costs of living alone.

As cohabitation leads to economies of scale, for instance in expenses on housing and utilities, couples have lower expenses per person than single individuals. Hence, the loss of a partner results in higher individual expenses. For people with a pension of their own in Slovenia, this loss is only partially offset by the survivor’s pension equalling 15% of the deceased person’s pension, unless the survivor’s own pension is much higher (about double) the deceased’s own pension. Disposable income remains stable for survivors without an old-age pension, as in that case the survivor’s pension equals 70% of the deceased person’s pension (Chapter 2).1

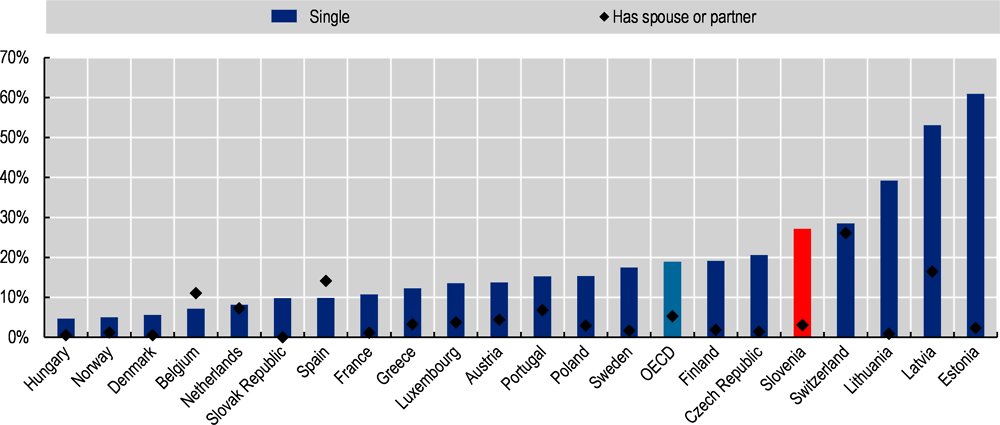

The equivalised disposable income of retirees living alone is significantly lower than that of retirees living together in Slovenia (Kump, 2017[4]). Single-person households accounted for 40% of retiree households, yet made up 61% of retiree households in the lowest three income deciles, based on 2014 EU-SILC data. Relative poverty rates among people aged 80+ in Slovenia are also highly dependent on whether or not people are single: 27% of Slovenians aged 80+ who are single live in relative poverty, compared to only 3% of people in the same age group with a spouse or partner (Figure 3.9). Indeed, the risk of poverty in old age is particularly concentrated among single people in Slovenia.2 Among European OECD countries, the relative poverty rate among single people older than 80 is only higher in Switzerland and the Baltic countries.

The high share of women living alone in old age (Figure 3.10) contributes to the relatively high gender gap in poverty rate in Slovenia. In all countries, many more women than men live alone, partly because they are more likely to be widowed, but this is even more the case in Slovenia. With 45% of women aged 65+ living in single-person households, Slovenia is among European OECD countries with a large share, and second only to Latvia. The Slovenian share is 5 percentage points higher than the EU average.

In sum, income inequality among older people is low, while relative income poverty and material deprivation among older Slovenians are close to the OECD and EU averages. Although relative poverty and material deprivation among older people have been declining, older women remain particularly vulnerable in old age. The high share of women living alone in old age contributes significantly to the high gender gap in old-age poverty.

This section deals with non-contributory first-tier benefits, i.e. residence-based basic pensions and safety-net benefits. It first presents safety-net benefits in Slovenia and then compares those to non-contributory benefits accessible to older people in other OECD countries in terms of benefit levels and coverage. Subsequently, extra support available to people receiving social assistance is discussed. Finally, safety-net benefit expenditure is analysed.

3.3.1. Description of safety-net benefits in Slovenia

The basis of Slovenia’s social assistance system is the Social Welfare Benefits Act (Zakon o socialno varstvenih prejemkih, ZSVarPre) that was adopted in 2010 and took effect as of January 2012. The law aims to provide support to people who cannot afford material security due to circumstances beyond their own control. The safety net for older people in Slovenia consists of two benefits, known as ‘financial social assistance’ and ‘supplementary allowance’. For financial social assistance, the same rules apply to people beyond the statutory retirement age as to all other adults, but the benefit level depends on employment status. Qualification for supplementary allowance is dependent on age and employment status.

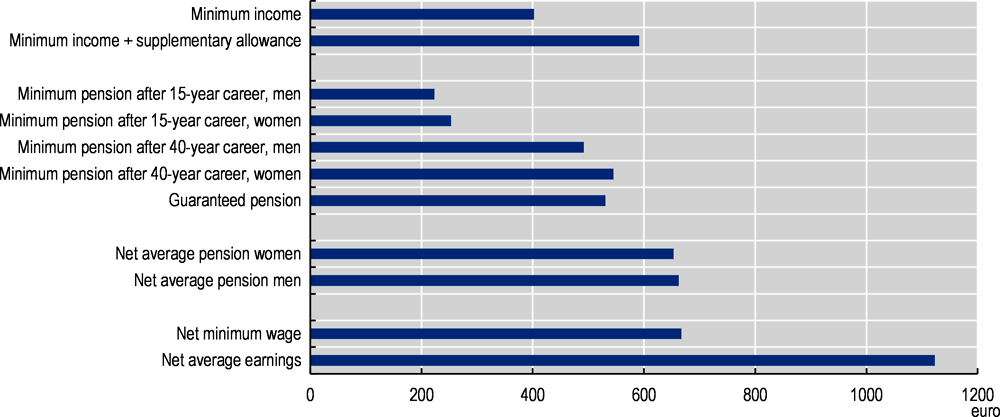

The purpose of financial social assistance (Denarna socialna pomoč) is to meet individuals’ minimum living needs by topping up household income to a threshold. The threshold for the first adult in the household is known as the minimum income (Minimalni dohodek) and is equal to EUR 402.18 per month in 2021, which is about 22% of gross average earnings or 36% of net average earnings. For every other adult in the household, the threshold increases by 57% of the minimum income (EUR 229.24). These benefit levels apply to persons working fewer than 60 hours per month.

The thresholds are higher for individuals working at least 60 hours per month at 126% of the minimum income (EUR 506.75), and at 151% of the minimum income (EUR 607.29) for individuals working more than 128 hours per month. For every other adult in employment, the threshold increases by 70% of the minimum income (EUR 281.53) and 83% of the minimum income (EUR 333.81), respectively.

Benefit amounts paid to older people are typically smaller than those paid to working-age people as for the former they top up earnings-related pensions. In 2019, the average financial social assistance benefit was EUR 355, whereas it was just more than half that amount, at EUR 189, among people aged 65+.

The means test assessing eligibility for financial social assistance also covers assets.3 Social assistance is not available to people owning the dwelling they live in if its value is above EUR 120 000, unless they comply with certain conditions, including an agreement that the state can reclaim part of the social assistance received at the time the dwelling is inherited – a rule that also applied to dwellings with a value below EUR 120 000 before 2017.4 Moreover, people cannot claim social assistance if their total eligible assets are valued over 48 times the monthly minimum income (that is, more than EUR 19 304.64 in 2021), with exemptions for the dwelling one lives in, the value of occupational and individual pension plans and a vehicle for personal use up to a value of 28 times the minimum income (EUR 11 261.04).5 In principle, adult children have an obligation to provide support to their parents if they are in need.6 As such, social assistance benefits are only available to people for whom financial family help is not possible. This can be the case because children do not have the means to support their parents, for instance if the children are social benefit recipients themselves, or because circumstances make it clear that the child will not support the parent, for instance in case of alienation or domestic violence.

The other benefit, the supplementary allowance (Varstveni dodatek), which used to be a supplement to low-income pensioners within the pension scheme, was transformed into a part of social assistance in 2012. The supplementary allowance is only available to people who are permanently out of the labour market, i.e. people who are permanently unemployable or unable to work due to disability, as well as to women older than 63 and men older than 65 who are not in employment. The benefit is designed to cover long-term living needs such as maintenance costs or replacement of household equipment.

The scheme effectively increases the threshold (to which benefits are topped up) for receiving social assistance benefits to 147% of the minimum income for a single individual (EUR 591.20) or to 229% of the minimum income (EUR 920.99) for a couple in which both people qualify. Hence, for single individuals, the maximum supplementary allowance benefit is 47% of the minimum income (EUR 189.02).7 In 2019, the average supplementary allowance benefit for people aged 65+ was EUR 167. The supplementary allowance is subject to the same asset test as financial social assistance.

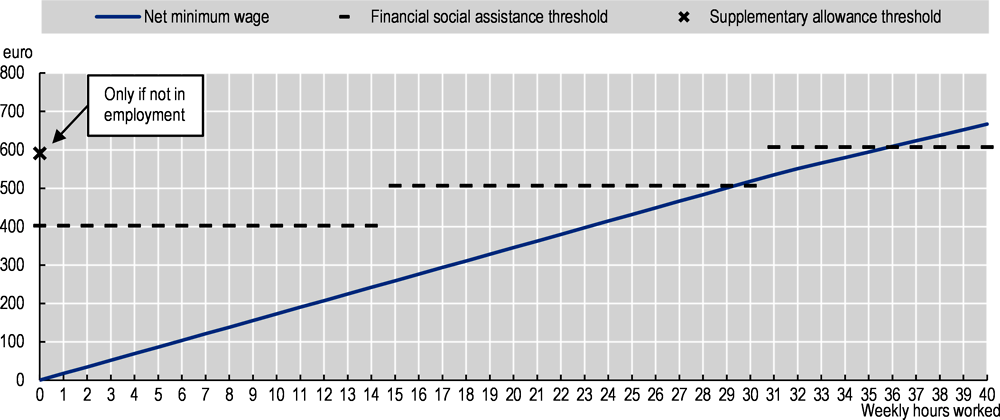

Considering financial social assistance and supplementary allowance together, it is clear that the Slovenian social assistance system provides a disincentive for women aged 63+ and men aged 65+ to enrol in any kind of employment (Table 3.1). As people above this age limit who are not in employment are entitled to both financial social assistance and supplementary allowance, the social assistance eligibility threshold applying to them is at 147% of minimum income (EUR 591.20) for single individuals. However, the moment they take up any employment, they can no longer receive the supplementary allowance, resulting in the social assistance threshold being lowered to the minimum income (EUR 402.18). A similar threshold as the combined financial social assistance and supplementary allowance threshold is only reached again for people working more than 128 hours per month. This disincentive comes on top of the suspension of full pension benefits for people combining work and pensions as detailed in Annex A in Chapter 1.

Men who are able to work become eligible to supplementary allowance upon reaching the statutory retirement age (at age 65), whereas women can receive the benefit already two years earlier as the eligibility age did not follow the increase in the statutory retirement age to 65 for women. As the statutory retirement age is an important social norm influencing the division between employment and retirement, it is inconsistent to assume that women remain eligible to supplementary allowance from the age of 63 years.

While the loss of supplementary allowance provides a disincentive to be employed, the increase of financial social assistance eligibility thresholds by working hours in only two steps provides limited incentives to work more hours. For a person receiving social assistance, monthly income is the same if one works 15 or 29 hours per week with low wages (Figure 3.11).

3.3.2. Assessment of benefit levels

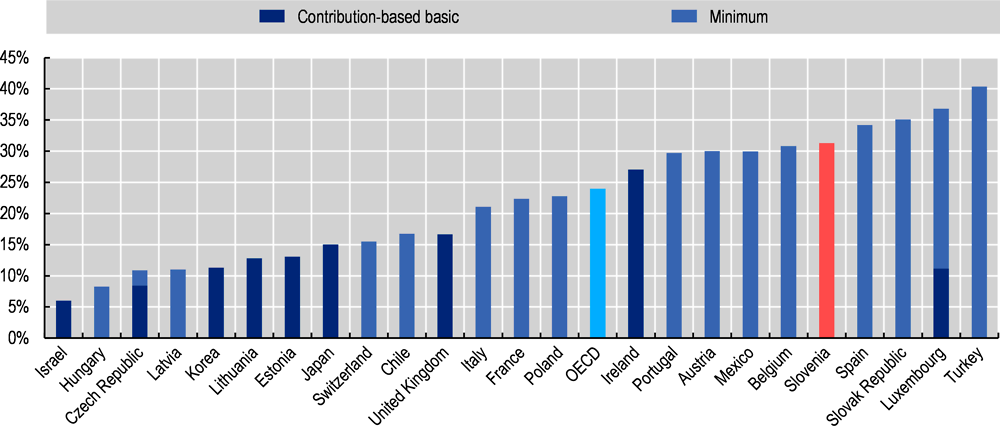

The levels of Slovenia’s non-contributory first-tier benefits are relatively high in international comparison. A single older person without any entitlements in the contributory pension scheme receives 29.8% of gross average earnings (EUR 591.20), compared to 20.7% on average in the OECD. Non-contributory pensions only exceed 30% of gross average wages in Canada, Denmark, New Zealand and Norway (Figure 3.12). New Zealand has no mandatory earnings-related pension, explaining the exceptionally high level of its residence-based basic pension. Canada, Denmark and Norway combine a residence-based basic pension with a targeted supplementary component.

Slovenia’s targeted scheme includes an asset test (more on this below), whereas the targeted schemes in Canada, Denmark and Norway are only tested against income. Income and asset tests generally apply to benefits allowing people to fulfil their basic living needs. Targeted to that purpose, asset-tested benefits in Slovenia are the highest in international comparison, followed by Australia, Belgium, Luxembourg and Portugal where benefit levels are around 28-29% of gross average earnings.

Financial social assistance and supplementary allowance are indexed to consumer prices. Hence, social assistance eligibility thresholds do not automatically keep up with increases in wages and average income. However, financial social assistance and supplementary allowance thresholds have grown much faster than price inflation or even wage growth over the last decade (Figure 3.13). In June 2018, they were sharply increased, by almost 30%. Discretionary adjustments have thus played a big role, and the large shift in June 2018 has deeply affected the consistency of non-contributory benefits that apply at older ages with first-tier contributory pensions (Section 3.4).

3.3.3. Coverage

Coverage rates for non-contributory first-tier benefits, measured as the number of recipients of a benefit relative to the population aged 65+, vary widely across OECD countries and benefit types (Figure 3.14). Coverage rates are highest in countries with residence-based basic pension schemes, covering on average 94% of the population aged 65+.8 Targeted schemes have significantly lower coverage rates, 16% on average.

With 3.4% of the Slovenian older population covered by targeted benefits, coverage is low. With roughly one in ten Slovenians aged 65+ living in a household with an income below the supplementary allowance eligibility threshold, calculations provided by IER show that 34.6% of those people effectively received supplementary allowance in 2020. This means that the combination of the asset test and non-take-up results in almost two in three older adults passing the income test not receiving the benefit. A comparison by Eurofound (2015[8]) shows that non-take-up rates of this level are high but not exceptional for social assistance benefits: they reach over 50% in many European countries and even over 70% in the Czech Republic, Portugal and the Slovak Republic.

Tight asset testing is likely to be an important factor of low coverage, contributing to the relatively high material deprivation rate among the older population (Section 3.2.2) despite high safety-net benefit levels. Although a wide range of factors impact coverage rates of targeted benefits, three elements play a crucial role. First, coverage rates and benefit levels of earnings-related pension benefits, minimum and basic pensions can reduce the number of people needing social assistance. Several countries with above-average coverage rates of targeted benefits provide neither minimum nor basic pensions, including Australia, Finland and Sweden. With the exception of Germany and the United States, all countries with below-average coverage rates have a minimum or contribution-based basic pension. This is also the case for Slovenia, which provides a minimum pension (Section 3.4).

Secondly, eligibility thresholds for social assistance restrict the number of possible applicants. In Central and Eastern European countries, the low level of targeted benefits presented in Figure 3.12 is associated with lower coverage rates than in Slovenia, with the exception of Poland. However, the high benefit level in Slovenia does not translate in a correspondingly high coverage rate. That is likely the result of the third factor: the stringency of the means test. Several countries with above-average coverage rates test only for income, not assets. This is for instance the case in Canada, Finland, Korea and Sweden. However, some countries, including Slovenia and Portugal, extend the asset test not just to the household, but also to children, substantially increasing the stringency of eligibility conditions.

The primary legal responsibility for financial assistance is placed with the family in Slovenia. People with insufficient means may not be eligible for social assistance benefits if they have children with sufficient means to support them. This responsibility may create an important disincentive for people to apply for social assistance in the first place, contributing to non-take-up. As the state will contact children to check whether they can support an applicant for social assistance, people may be reluctant to apply in the first place in order not to inconvenience their children, or to hide their own neediness for the people around them out of shame.

Economically, the legal obligation for children to provide assistance is effectively a tax on social mobility. As richer older people do not need financial assistance and poor older people with poor children qualify for safety-net benefits, only children of poor parents who have managed to build a better life for themselves economically would end up being forced to step in to pay for financial assistance to their parents. As such, the obligation to provide for older parents contributes to the transfer of disadvantage from one generation to the next, perpetuating income positions across generations and stifling social mobility.

Elsewhere, for instance in Belgium, children and grandchildren are excluded from the means test and the assessment of the benefit level even if living in with the older person. The goal of the policy is to neither force family solidarity nor penalise it by withdrawing benefits when children step in to provide assistance to their parents.

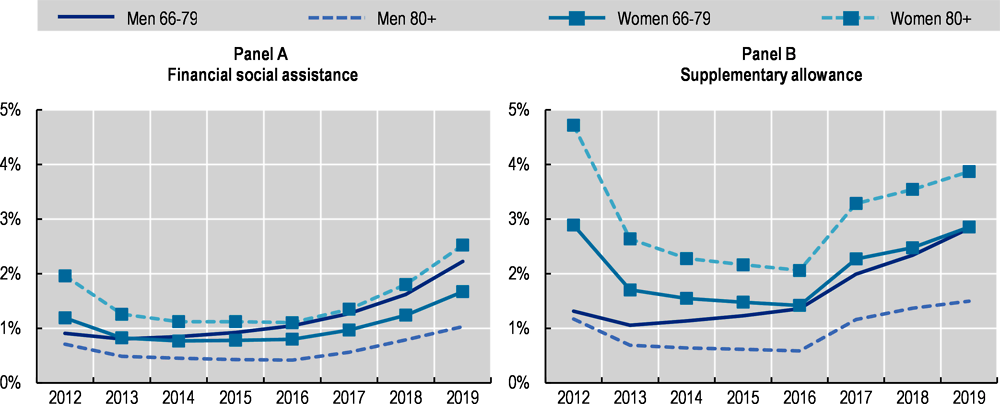

While remaining low, social assistance coverage has been on the rise since 2016 (Figure 3.15). The increase in uptake of financial social assistance and supplementary allowance coincides with increases in eligibility thresholds, resulting in more people qualifying for these benefits. In 2019, 2.5% of women and 1.0% of men aged 80+ were covered by financial social assistance benefits, whereas in the age group 66-79 this was respectively 1.7% and 2.2% (Panel A). The lower share of beneficiaries among men aged 80+ than among those aged 66-79 likely reflects the initially higher effective accrual rates that have systematically been reduced since the 1990s.

The share of the older population receiving the benefit is higher for the supplementary allowance than for financial social assistance as the maximum limit for the income test is higher (Panel B). In 2019, 3.9% of women and 1.5% of men aged 80+ were covered by a supplementary allowance, whereas in the age group 66-79 this was 2.9% and 2.8%, respectively.

Since the supplementary allowance was transferred from the pension system to social assistance in January 2012, it has been awarded to a household rather than an individual and became subject to the asset test. This resulted in a drastic drop in supplementary allowance beneficiaries from around 46 750 on 31 December 2011 to around 13 100 in 2012. The drop was largely caused by people no longer qualifying under the new conditions, although some 9 800 recipients renounced their right by 1 January 2012 (ZPIZ, 2012[10]). This is likely also the reason for a further drop in beneficiaries between 2012 and 2013 (Panel B). Since then, the share of older people benefiting from a supplementary allowance has followed roughly the same pattern as for financial social assistance. Moreover, for people owning their own dwelling, the amount of financial social assistance and supplementary allowance received had to be reimbursed after they passed away, but since February 2017, dwellings with a value below EUR 120 000 are exempt from this rule. This likely explains the hike in beneficiaries in 2017, whereas the big increase in benefit level only occurred in 2018.

3.3.4. Other safety-net benefits

A rental subsidy (Subvencija najemnine) is available to tenants. A household is eligible for a rental subsidy if 70% of household income is lower than a ceiling equal to the sum of: the minimum income level for the type of household; and, the amount of ‘not-for-profit rent’ – an administratively set value determined by dwelling size, location and a number of costs for the owner including maintenance, management, financing and depreciation.9 The subsidy is equal to the difference between the ceiling and 70% of the household’s total income, and is maximally 80% of the not-for-profit rent. For a single older person living in a 30m2 apartment valued at the maximal not-for-profit rent, the rental subsidy is EUR 91 per month if the person receives the supplementary allowance.

Medical and care expenses affect social assistance recipients in a number of ways. Healthcare is free for people receiving social assistance benefits. Adults in institutional care are entitled to financial social assistance at the full minimum income of EUR 402.18, but not to supplementary allowance. Furthermore, there is an Assistance and Attendance Allowance (Dodatek za pomoč in postrežbo) available to people who need help from another person to carry out activities of daily life (ADLs).10

Extraordinary financial social assistance (Izredna denarna socialna pomoč) is available for a period of up to six months, or paid as a lump-sum, to finance an acute material need that cannot be covered by either the recipient’s own or the family’s income. The maximum benefit is the full minimum income (EUR 402.18 per month) for a single individual or up to EUR 1 106.00 for a family in 2020. The benefit application has to contain a specific purpose for the benefit, and the recipient has to provide evidence that the benefit received was spent accordingly. The benefit can be used to cover such things as utility and heating expenses, or purchases of household equipment such as a washing machine or a stove. A benefit of one month of minimum income is available to cover expenses of a funeral of a family member, and a benefit up to 5 months of minimum income can be applied for to cope with the consequences of misfortunes such as natural disasters.

3.3.5. Safety-net expenditures

Expenditure on safety-net benefits for older people is very low in Slovenia, although it has risen in recent years. Expenditure reached EUR 34 million in 2019, representing less than 0.1% of GDP (Figure 3.16). The recent increase reflects higher social assistance eligibility thresholds as shown in Figure 3.13 and a higher number of beneficiaries as presented in Figure 3.15.

The contributory pension scheme also contains some features to reduce financial vulnerability in old age, notably the minimum pension and the guaranteed pension. In this section, both schemes are presented and compared to minimum pensions and contributory basic pensions in other OECD countries. First, qualifying conditions are compared, then benefit levels, and finally coverage. The last section will discuss their interaction with non-contributory benefits.

3.4.1. Description of minimum and guaranteed pensions in Slovenia

Slovenia has two pension provisions that can be classified as minimum pensions in the typology of first-tier benefits: the minimum pension per se (najnižja pokojnina) and the guaranteed pension (zagotovljena pokojnina). The minimum pension is based on the same accrual rates as earnings-related pensions, but is calculated based on a minimum reference wage. The minimum reference wage (also known as the minimum pension base, najnižja pokojninska osnova) equals 76.5% of the average economy-wide monthly salary in the previous year, net of taxes and contributions.

Same accrual rates as for earnings-related pensions mean that once a person qualifies for an old-age pension, after 15 years of contributions, the minimum pension equals 29.5% of the minimum reference wage for women and 27.5% for men in 2021. The rate for men was set to increase to the rate of women by 2025 in increments of 0.5 percentage points per year, but in 2021 it was decided to shorten the transition process reaching gender neutrality in accrual rates by 2023. For every year of contributions after 15 years, the accrual rate is 1.36% for women and 1.28% for men in 2021, with men catching up here also by 2023. Moreover, after reaching 40 years of pensionable service without purchase and 60 years of age, there are additional accruals of 3% for every extra year of contributions for a period of up to 3 years, after which the accrual rate falls back to 1.36% and 1.28% for women and men, respectively.

Through the minimum reference wage, the minimum pension for new retirees is indexed to wage growth. For people drawing a pension for the first time in 2021, the minimum pension is equal to EUR 269.27 after a 15-year career for both men11 and women, and EUR 543.10 for men and EUR 579.62 for women after a 40-year career. For women – and then for everyone in the future – this represents approximately 24% of economy-wide net average earnings after 15 years and 51% after 40 years. During retirement, the minimum pension follows the same 60-40 indexation mechanism that applies to all pensions.

As the minimum pension was considered insufficiently rewarding after a career of 40 years, a push for a higher pension led to the introduction of the guaranteed pension in 2017, guaranteeing a pension of at least EUR 500 per month for careers of at least 40 years of pensionable service without purchase. At the end of 2020, the guaranteed pension only affected men as the minimum pension after a 40-year career for women exceeded the guaranteed pension. Moreover, as men’s accrual rates will converge towards those of women, the guaranteed pension would have no longer provided any supplementary income to the minimum pension for men either, making it obsolete. However, as part of the 2021 measures, the guaranteed pension was increased by 9% from EUR 566.88 to EUR 620 per month, which is about 49% of average net earnings. Hence, it currently supplements men’s monthly minimum pension after a 40-year career by about 14% (EUR 76.90) and women’s (as well as men’s as of 2023) by about 7% (EUR 40.38). For both new pensions and pensions in payment, the guaranteed pension is indexed in the same way as other pension benefits (60% wages and 40% prices).

3.4.2. Assessment of qualifying period

A career of 15 years is required to access the minimum pension in Slovenia, with the guaranteed pension effectively providing a top-up after a 40-year career. The 15-year career is counted in full-time equivalents with working hours compared to a 40-hour work week (Chapter 2), meaning that a person permanently working on half-time contracts becomes entitled to the minimum pension after 30 years. Several countries with minimum or contribution-based basic pensions also require at least 15 years of contributions, including Austria, the Baltic countries, Greece, Portugal, Spain and Turkey (Figure 3.17). While minimum career requirements to qualify for contribution-based basic pensions range from 5 to 15 years, minimum pension schemes vary more widely in the career length required to qualify. People have access to the minimum pension after at least one-quarter of contributions in France and 12 months in Switzerland, but qualification requires 30 years in the Czech and the Slovak Republics.

Countries also vary widely in the amount of years of contributions required to qualify for a full minimum pension, ranging from 15 years in Spain and Turkey to 44 years in Switzerland and 45 years in Belgium. In Slovenia and the Slovak Republic, there is no maximum minimum pension: the minimum pension increases with every extra year of contributions paid, without an upper limit to the number of years of contributions accounted for in the minimum pension. Only in Estonia, Spain and Turkey do 15 years of contributions result in a full minimum or contribution-based basic pension. In Belgium, Luxembourg and the Slovak Republic, however, people only qualify for a partial minimum pension after 20 or 30 years of contributions.

3.4.3. Assessment of benefit levels

At 31.3% of gross average earnings in 2021, Slovenia has among the highest levels of minimum pensions after a full career among OECD countries (Figure 3.18). Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, Spain and Turkey have 34% or more, while the full benefit is close to 30% in Austria, Belgium, Mexico and Portugal. Among OECD countries with a minimum pension, the average full benefit is 24.0% of gross average earnings. The full minimum pension in Spain and Turkey reaches an even higher level and is eligible after only 15 years of contributions. As low pensions are not taxed in Slovenia (Chapter 2), the full minimum pension expressed as a percentage of net earnings is even comparatively higher for Slovenia.

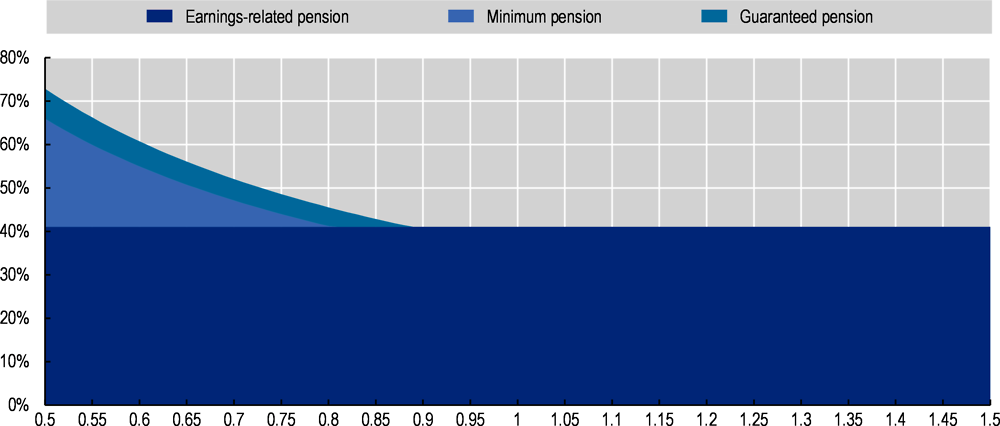

The minimum and guaranteed pensions have a large impact for low earners. For a person with a full career, the future gross replacement rate of the earnings-related pension is 41.0% whatever the earnings level below twice average earnings. However, the minimum pension provides a top-up to people with a 40-year career at earnings up to 80% of average earnings and the increased guaranteed pension benefits people up to 88% of average earnings. At 50% of average earnings, the minimum and guaranteed pensions will increase the future gross replacement rate to 72.8% in total (Figure 3.19).

The minimum pension is more important for women than for men as 45% of women and 30% of men receive an old-age pension below EUR 600 (Figure 3.20). Moreover, minimum pensions have gained in importance among recent cohorts of pensioners. Indeed, the share of new pensioners receiving a benefit at the minimum reference wage rose from 17% of men and 32% of women in 2013 to 30% of men and 38% of women in 2019 (ZPIZ, 2020[11]).

3.4.4. Coverage

Among contributory first-tier benefits, contribution-based basic pension schemes have very large coverage rates (Figure 3.21, Panel A) as there is no associated income test. By contrast, minimum pensions only benefit recipients whose earnings-related entitlements are low such that they can be topped up to the minimum pension level. The average coverage rate for minimum pension schemes is 24% in OECD countries with such a scheme (Panel B).

The Slovenian coverage rate for the minimum pension scheme of 23% is thus similar to this average. Among the ten OECD countries having a minimum pension for which coverage rates are available, the coverage is larger than 30% in Belgium, France, Italy and Portugal, while it is low in other Central and Eastern European Countries (Hungary, Latvia and the Slovak Republic).

3.4.5. Interplay between safety-net benefits and minimum and guaranteed pensions

Figure 3.22 shows that the supplementary allowance eligibility threshold was just about 10% below the average net pension in 2019. Moreover, after 40 years of contributions, the minimum pension was 17% lower than the average net pension for women, and the guaranteed pension 20% lower than the average net pension for men – the difference between the average pension and the guaranteed pension will be smaller in 2021 due to the increase in the guaranteed pension. The minimum and guaranteed pension contribute significantly to compressing the low part of the pension distribution, as seen in Figure 3.20. In 2019, taking into account the pensions for all cohorts of retirees, which are determined by initial pensions when retiring and indexation, the net average pension was equal to 59% of the net average wage.

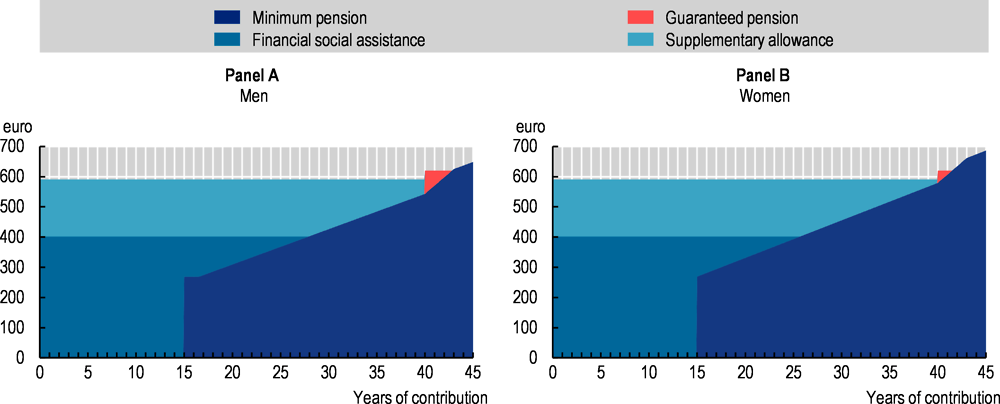

While in 2019, the levels of social assistance benefits were larger than the minimum and guaranteed pensions, the substantial increase in the guaranteed pension in 2021 brought its level above the supplementary allowance eligibility threshold. For the 2021 numbers shown in Figure 3.23, the income limit for the supplementary allowance at EUR 591.20 for an individual exceeds the minimum pension of EUR 579.62 for women and EUR 543.10 for men after a 40-year career, but is now below the guaranteed pension of EUR 620.00. The minimum pension only exceeds the supplementary allowance eligibility threshold after a career of 41 years for women and 43 years for men.

With the safety-net eligibility threshold exceeding minimum pension levels, is the minimum pension an obsolete instrument in providing basic income security to older people who have contributed to old-age pensions? Given the low coverage of safety-net benefits, the minimum pension remains an important instrument to reduce old-age poverty. This is because, among couples in which both partners have long careers, minimum pensions are not adjusted to family size, as is standard in all countries. Moreover, a normative argument could be made to provide better minimum income protection to people who have contributed more. The current unusual hierarchy of benefit levels is the result of the sharp discretionary increase in the safety-net benefits in 2018. However, it currently has limited implications because of the stringent conditions embedded in the asset test and the resulting low coverage of the safety nets as discussed in Section 3.3.

As the minimum pension is pegged to the evolution of average wages whereas social assistance benefits are in principle only adjusted to price inflation, minimum pension benefits grow faster than safety-net benefits in a normal economic environment. Hence, the balance between minimum pension and safety-net benefits changes over time. The minimum pension has been catching up with the safety-net eligibility threshold again since the steep increase in 2018, reducing the difference from 17% for men and 8% for women in 2018 to 11% and 4% in 2020, respectively.

This nexus further illustrates the need for stronger co-ordination of first-tier benefits for older people. A more deliberate balance should be sought between safety-net eligibility thresholds and the minimum pension to improve transparency, provide basic income security to older people and offer some extra benefits to individuals contributing to the pension system.

Slovenia has a low level of income inequality among both the working-age and the old-age populations and, thanks to recent improvements, has relative poverty and material deprivation levels close to the OECD averages. Old-age poverty is particularly concentrated among older people living alone in Slovenia, which is an important factor in the large gender gap in relative old-age poverty – despite a low gender pension gap in international comparison – as women are more likely to live alone in older age.

The minimum pension plays a big role within contributory pensions, by effectively topping up low pensions in relation with the contribution period. In addition, Slovenian safety-net benefits provide a high level of support to a very selective group of people. Social assistance benefits are high relative to average earnings in a comparative perspective, but coverage rates are low.

The analysis highlights a number of issues in the design of first-tier benefits in Slovenia. First, coverage of social assistance is very low despite high threshold levels. This is likely the consequence of the obligation of family members including adult children to provide financial support to individuals in need. As the state contacts family members to check whether they can support an applicant for social assistance, people may decide not to apply for the benefit for various reasons. They might do so to avoid being a burden on their family members, because they believe it is not right that children should support their parents, or in order to try to hide their own neediness from the people around them out of shame.

The legal obligation for the family to provide financial assistance effectively is a tax on social mobility. As richer older people do not need financial assistance and poor older people with poor children qualify for safety-net benefits, only children of poor parents who have managed to build a better life for themselves economically would end up being forced to step in to pay for financial assistance to their parents. As such, the obligation to provide for older parents contributes to the transfer of disadvantage from one generation to the next, perpetuating income positions across generations and stifling social mobility.

Secondly, the social assistance and minimum pension schemes should be better co-ordinated. The safety-net level prevents that low or middle earners are rewarded for having contributed to their pensions even in case of long careers. A person with a minimum pension for a full career can still be entitled to social assistance as safety-net eligibility thresholds currently exceed the minimum pension after a full career. Yet, this was not the case before the large increase in the safety-net threshold in 2018. The 2021 increase in the guaranteed pension only overcomes this problem to a small extent. On top of this issue, as eligibility for supplementary allowance depends on being permanently out of employment, the benefit discourages eligible people from engaging in any kind of formal employment as that would result in the loss of the benefit. There is a need for a more deliberate balancing of safety-net eligibility thresholds and minimum pension to provide basic income security to older people while providing additional benefits based on past contributions. Moreover, the eligibility age to the supplementary allowance for women is no longer aligned with their statutory retirement age since the latter increased to 65 years.

References

[8] Eurofound (2015), Access to social benefits: Reducing non-take-up, https://doi.org/10.2806/651436.

[4] Kump, N. (2017), Socialno-ekonomski položaj upkojencev in starejšega prebivalstva v Sloveniji [Socio-economic situation of pensioners and the older population in Slovenia].

[3] OECD (2021), Employment rate (indicator), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1de68a9b-en (accessed on 26 January 2021).

[1] OECD (2020), OECD Economic Surveys: Slovenia 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/a4209041-en.

[6] OECD (2020), Taxing Wages 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/047072cd-en.

[5] OECD (2019), “Earnings: Nominal minimum wages (Edition 2019)”, OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (database), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/97e15391-en (accessed on 1 December 2020).

[7] OECD (2019), Pensions at a Glance 2019: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/b6d3dcfc-en.

[9] OECD (2018), OECD Reviews of Pension Systems: Latvia, OECD Reviews of Pension Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264289390-en.

[2] Vodopivec, M. and S. Hribar-Milic (1993), The Slovenian labor market in transition : issues and lessons learned.

[11] ZPIZ (2020), Beneficiaries of entitlements from pension and disability insurance 2019.

Notes

← 1. However, if both partners had an equally high pension before, the survivor’s pension would have to be at 41% of the deceased person’s pension for the equivalised income of the surviving partner to remain at the same level as before the passing of the spouse. This is based on the OECD equivalence of scale dividing household income by the square root of the household size.

← 2. More precisely, 88% of people aged 65+ with an income below the relative poverty threshold are single, whereas only 37% of people with an income above the threshold are single. In the age group 80+, this is 94% and 59%, respectively.

← 3. For people who are permanently outside the labour market, referring to people who are permanently unemployable or unable to work due to disability, as well as women aged 63+ and men aged 65+ who are not in employment, social assistance is granted for a period of up to one year at a time. Total income net of taxes and contributions over the three months preceding the application for social assistance is assessed.

← 4. Under some circumstances, a person can be eligible for social assistance benefits despite living in a dwelling one owns that is valued above EUR 120 000. If the owners temporarily would not be able to sustain themselves through the dwelling for reasons outside their control and otherwise qualify for social assistance, they can claim social assistance for up to 18 months in a 24-month period. After that period, they can claim social assistance on the condition that they accept a restriction on alienation and encumbrance of the property in the land register at the benefit of the Republic of Slovenia. At the moment that the dwelling is inherited, then, the Republic of Slovenia reclaims from the inheritance two-thirds of the social assistance received, reduced by 12 maximum monthly amounts of the social assistance received.

← 5. Other real estate up to a value of EUR 50 000 is exempt, as are personal savings up to EUR 2 500, and family savings up to EUR 3 500. For employed individuals, the exemption for savings is limited to three times the minimum income (EUR 1 206.54) for the individual’s savings and to EUR 2 500 for family savings.

← 6. Children are obligated to provide support to their parents who are in need for as long as their parents supported them, i.e. for as long as the child was in education or not in employment, and for at least 18 years.

← 7. And 25% of the minimum income for every subsequent qualifying adult (EUR 100.55).

← 8. The Latvian residence-based basic pension is not included in the average coverage rate of 94.0% across residence-based basic pension schemes in the OECD. The Latvian basic pension is only accessible to retirees without a pension entitlement from the social security system. Due to the full-employment policy deployed under the former Soviet regime and the rather beneficial treatment of non-employment spells in the social security system until 1996, few retirees qualify for the basic pension. Fewer than 0.1% of people aged 65+ in Latvia were covered by the basic pension in 2017 (OECD, 2018[9]).

← 9. Legally, a household is eligible to a rental subsidy if the household income does not exceed the minimum income for the household type (without work allowance), increased by 30% of household income and the amount of not-for-profit rent. Mathematically, this is the same as stating that 70% of household income should not exceed the sum of the minimum income for the household type (without work allowance) and not-for-profit rent.

← 10. In 2020, the Assistance and Attendance Allowance benefit is EUR 150 if help is required for the majority of activities of daily life (ADLs), EUR 300 if it is needed for all ADLs and EUR 430.19 if the person is severely disabled and in need of 24-hour care.

← 11. As part of the 2021 decision to speed up of the convergence of men’s accrual rates to women’s, the minimum pension for men after 15 years of contributions was set at the same level as that of women already as of 2021.