Overview: Innovative approaches to building resilient water infrastructure in the Mekong region

This overview summarises the main points contained in the five chapters of the publication on Innovation for Water Infrastructure Development in the Mekong Region. Chapter 1 provides a snapshot of the key socio-economic and environmental challenges facing the Mekong River and underlines the importance of transboundary initiatives to address these challenges. Chapter 2 explores the benefits of innovative financing models enabled by technologies, such as crowdfunding and tokenisation. Chapter 3 analyses infrastructure investment needs and focuses on spillover tax revenues to boost private sector participation. Chapter 4 presents a variety of initiatives that could enhance the resilience of water infrastructure in the face of natural disasters, putting particular emphasis on community engagement and digital tools. Chapter 5 completes the picture with a discussion about the weaknesses of water and wastewater regulations in the Mekong countries and highlights a few priority areas for reform.

The Mekong River originates about 5 200 metres above sea level at the Tibetan Plateau and discharges into the South China Sea after travelling 4 350 km. The annual economic value of water-related sectors in the Mekong River Basin (MRB) is estimated at almost USD 35 billion, excluding forestry and tourism. The benefits derived from the Mekong River system are multi-dimensional; with social, economic, environmental and other aspects. The river provides irrigation for agriculture, fisheries, transportation, water supply, hydropower, tourism-related opportunities and sediment extraction. Agriculture and irrigation are the major beneficiaries of the Mekong River, using 70% of its water resources. The total irrigated area in the basin is approximately 4 million hectares, and irrigated areas are expanding steadily in four countries (Cambodia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Thailand, and Viet Nam). Thailand and Viet Nam continue to draw the greatest economic benefits, particularly from agriculture and fisheries, including aquaculture. Lao People’s Democratic Republic (hereafter ‘Lao PDR’) is generating most of its economic benefits from Mekong resources through investment in hydropower. Meanwhile, Cambodia continues to enhance fisheries. However, the countries need to cope with socio-economic and environmental challenges, including those posed by climate change.

Climate change poses risks to the river and the countries in its basin. It could affect water security in the MRB and the life of its inhabitants. The changes of weather patterns affect the agriculture production cycle and fish breeding. Meanwhile, changes in water level and flow affect the navigation route and operation of hydropower plants and reservoirs. The wet season increases vulnerability to floods, while the dry season suggests greater potential for drought periods. Expansion of agriculture in the basin is limited by water availability in the dry season. Climate change also threatens biodiversity in the MRB. As climate change alters water availability, changing rainfall patterns could reduce or change the flow of rivers, threatening the generation potential of hydropower.

Strengthening transboundary co-operation

Due to the transboundary nature of the river, MRB countries need to strengthen co-operation to implement basin-wide climate adaptation measures. Co-operation enables joint development of more cost-effective solutions, which potentially offer benefits to all riparian parties.

MRB countries have implemented a number of projects and programmes through their governments, transboundary co-operation or donor support. These target various sectors, including climate-smart agriculture, green freight, food security, sustainable fisheries and alternative sources of green energy. However, the benefits of co-operation mechanisms in climate adaptation are not widely realised, often due to competing economic interests among the MRB countries and emphasis on using the Mekong River as a water resource.

Innovative approaches are needed to address various new challenges. Innovation for Water Infrastructure Development in the Mekong Region covers the topics of digital infrastructure financing, spillover effects of water transport, resilience to natural disasters, and challenges of water regulation, following an overview of socio-economic and environmental challenges.

Asia, including the Mekong region, has significant financing needs for infrastructure, but has difficulties obtaining suitable financing from sources beyond the public sector (OECD, 2018[1]). The public sector continues to finance the majority of infrastructure in Asia and the Mekong region, although the private sector is increasingly involved through public-private partnerships (PPPs) and privatisation. In total, approximately 70% of Asian infrastructure funding comes directly from the public sector. The private sector contributes 20%, while multilateral agencies, such as international development banks, contribute the rest.

Public sector funding draws on tax and non-tax revenues, as well as borrowing and loans from multilateral institutions. Private sector participation leans more on the debt market, especially bank lending, even though relying on banks to fund infrastructure poses challenges. Since banks’ loanable funds are largely composed of demand deposits, the tenor of their investments is limited to shorter periods. Performance and asset quality ratios demanded of banks in a well-supervised environment also limit the volume of loanable capital. Furthermore, traditional lending by banks often gives limited attention to community needs and interests. Equity issuance and corporate bonds of entities directly involved in infrastructure sectors such as utilities, transportation and mining represent other sources of funding. Institutional investors such as sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and insurance companies have increasing interest in infrastructure as an asset, but current policy fails to facilitate this funding mechanism, with investor regulation representing one of the major constraints. The market for securities is also generally at an early stage of development in many countries, therefore opportunities for countries in the region to develop alternative financing mechanisms beyond the public sector are plentiful.

Developing alternative and innovative funding channels

Tools using digital technologies could be potential alternatives. Such platforms can help surpass the limits of traditional banks, providing a lower entry cost for retail investors. They can also indicate community support, sending a reassuring signal to larger institutional investors. Technology-enabled financing platforms have grown significantly in the last few years and become a popular choice for small projects that would have had difficulty obtaining capital from traditional creditors. Crowdfunding and tokenisation are some examples, although the use of these tools to finance public infrastructure remains limited.

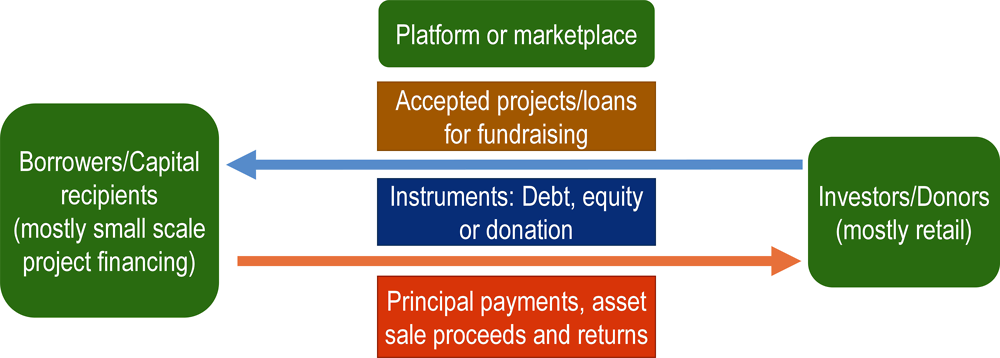

Crowdfunding is one way for individuals or participants to pool funds to finance businesses, projects, or other needs of enterprises or individuals. In general, crowdfunding can take the form of debt, equity, royalty, reward or donation. In a crowdfunding system, fundraising mainly involves the investor, the capital recipient or the borrower, and the marketplace platform (Figure 0.1). The link between the investor and the capital recipient is more direct compared to the banking system.

Tokenisation is another potential option to raise capital for infrastructure either through debt or equity. Tokenisation lessens reliance on traditional intermediaries in the flow of funding. After government-issued funds (fiat money) are converted into tokens, payment, clearing and settlement would no longer pass through banks, custodians and clearinghouses. This will then lower the cost and financial barriers to investor participation. Tokenisation in the context of infrastructure divides the value of assets or the underlying securities (debt or equity) into smaller parcels before they are offered to potential investors (Figure 0.2). Thus, tokenisation could be used to foster liquidity in an asset market that is typically illiquid, such as real estate. Moreover, tokens carry relatively lower transaction costs than traditional securities; their digital nature makes their usage more efficient, while blockchain technology enhances transparency.

Exploring the use of technology-enabled financing platforms

Crowdfunding and blockchain tokens have been used to finance various projects, including those in agriculture, the arts, health, fashion, retail goods and technology. In water-related infrastructure, digital financing based on Fintech and blockchain technology, in particular crowdfunding, has emerged as an important source of funding. It has already been applied in various OECD and Asian countries. Fintech-based finance efforts, in particular, often support the water infrastructure needs of local communities. Table 0.1 highlights some successful examples: 1) the Pitak Project in the Philippines; 2) the water purification project in Branson, Colorado, United States; 3) the project to improve water quality in Buttah Windee, West Australia; 4) the Water for Arubot project in Nepal; and 5) the water vending machine in Ngomai, Tanzania. Strong need expressed by the community, together with transparency and promotion, are some of the key success factors.

Despite some successful examples, the use of crowdfunding and tokenisation to finance public infrastructure in the region is still limited. It is mainly for last-mile needs and largely based on donations. However, progress in using alternative financing to develop projects in real estate, transport, power and water could set the stage for a broader usage of these platforms in general public infrastructure financing in the coming years. Continued growth of Fintech will depend on adequate risk assessment, especially for large transactions like infrastructure projects. The availability and depth of secondary markets for transactions is another important factor in facilitating the use of alternative platforms in an effective manner.

Countries in the region need various kinds of infrastructure investment, including electricity supply, water supply and sewerage. Water is a necessary public good. While the public sector supplies most water, private investors could help expand water networks and thus increase water supply. PPPs have long been discussed as a potential strategy for the sector. However, many countries have struggled to attract the private sector especially due to low returns on such projects. Water supply and many other infrastructure investments rely on user charges as their main source of revenue. Unless user charges are high enough to cover the costs of construction and operation, attracting the private sector to invest in infrastructure is difficult. If returns were high enough, private investors such as insurance companies and pension funds could also finance water supply, sanitation and inland water transport. If private sector involvement were to supplement public sector spending on infrastructure (rather than replacing it), the range of possible infrastructure developments would be expanded. Realisation of some of these possibilities would then lead to economic growth, job creation and mitigation of income disparities.

Attracting private sector investment by using spillover tax revenues

Water infrastructure investments increase productivity, in addition to creating significant spillover effects for the economy. New business opportunities will arise along the water supply, attracting commercial and manufacturing activities as well as tourists. This, in turn, will increase property values and create new employment. A safe and reliable water supply will also improve the health of people in the region, contributing to higher productivity. The externality effects of infrastructure investment are difficult to measure; however, the impact of these effects on the economy will be reflected through increased tax revenues.

Case studies illustrate the spillover effect of infrastructure. The economy of urban and rural areas along the railway in Uzbekistan grew by 2% more than in other regions. This difference was due to the spillover effects after the railway connected the production region to the market, creating substantial tax revenues. In the case of the Star Highway in Manila, tax revenues increased from around PHP 490 billion prior to construction to over PHP 622 billion and PHP 652 billion after construction had started. Tax revenues amounted to PHP 1 208 billion starting with the fourth year, about twice as much compared to the pre-construction period.

In the past, all these incremental tax revenues benefitted governments, while private companies relied solely on user charges for their source of returns. The low returns discouraged private sector involvement in financing water infrastructure projects. Water infrastructure thus relied almost exclusively on public money, which restricted expansion in many countries in Asia. Partly returning spillover tax revenues to investors would increase the rate of return. This, in turn, would provide private investors with an incentive to invest in the project. If part of the increased tax revenues were returned to water transport businesses, user charges could be kept low. Furthermore, spillover tax revenues will create additional revenues for the port authority, supplementing user charges. The port authority can invest these revenues into continued economic development, either through new projects or the maintenance of existing ones.

Water infrastructure, including water supply and inland water transport, will have a bigger economic impact in regions with larger population densities. Rural regions may not be able to create such sizeable spillover effects and the incremental tax revenues might be smaller. The government can therefore set up a cap for private investors. This means that if the total rate of return (part of spillover tax revenues and user charges) surpasses the cap, the government would take the remainder of increased tax revenues and use them to develop and enhance water supply to rural regions.

Natural disasters can slow or reverse development by destroying infrastructure and other forms of physical capital. The impact of natural disasters on water infrastructure can drive communities back into difficulties, especially in areas where the economy relies heavily on agriculture. Damage to water infrastructure caused by natural hazards may contaminate water and disrupt service provision, leaving communities with unsafe and unreliable water supplies. This can increase the exposure of communities to water-borne diseases, especially during flood events. In addition, environmental degradation due to human overexploitation can reduce the capacity of ecosystems to protect against natural hazards, thus increasing vulnerability to disasters. Multi-purpose infrastructure, including nature-based solutions, as well as community-based disaster risk management may help improve resilience against natural hazards, although a number of challenges remain to be addressed. Water infrastructure resiliency became a foremost concern during the recent COVID-19 outbreak due to the necessity of access to clean water to maintain health and prevent the spread of disease.

Adapting to natural disasters with multi-purpose water infrastructure

With the increasing risk of exposure to natural disasters, conventional water infrastructure – often single-purpose and with limited capacity in terms of disaster mitigation – is becoming more vulnerable to natural hazards. Multi-purpose water infrastructure projects that address economic, social and environmental concerns may help. In Mekong countries, multi-purpose water infrastructure is still rare. Multi-purpose dams account for only 1% of total dams in the Mekong basin (Cambodia, Lao PDR, Thailand and Viet Nam). A single-purpose dam is often more financially attractive for private investors, as it has lower risks and secure financial returns on the energy produced. Thus, financing for multi-purpose dams often comes almost exclusively from public resources. The lack of joint planning between border provinces is another challenge to resilient water infrastructure development in the region.

Strengthening urban resilience with nature-based solutions

Interventions in ecosystems inspired and supported by nature (nature-based solutions or NBS), have often been considered as complements or even substitutes to conventional infrastructure. This concept may offer effective and low-cost solutions to increase resilience, while delivering other benefits such as biodiversity, air quality or even possibilities for recreational activities. NBS can also be implemented to achieve water-related objectives, such as wetlands restoration for improving water resource management and boosting resilience against water-related hazards. A type of NBS called water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) may gain importance as cities become more vulnerable to the effects of environmental degradation and disasters induced by climate change. WSUD tools are flexible enough to be integrated into any type of urban development, such as building units, parks and other open spaces with waterways. The concept may thus offer solutions for cities to become more resilient and liveable, while providing vibrant spaces for communities. As the concept is relatively new for most developing cities in Mekong countries, strong commitment and political leadership, as well as community engagement, may be needed.

Using community-based solutions for better disaster resilience

Resilience against natural hazards may also depend on institutional capacity to prepare for disasters. Fragmented sectoral approaches and institutional arrangements could render the implementation of disaster risk management more difficult. Lack of information and technical skills to execute plans are additional challenges that hinder disaster preparedness. It is also crucial that communities are engaged as community-led co-ordinating mechanisms are often cost-effective since local needs and circumstances can be addressed properly.

Cambodia

The National Committee for Disaster Management is the main government structure in terms of co-ordinating actions related to disaster risk reduction (DRR). The country has implemented several community-based programmes. However, limited resources and information sharing with all levels of the government sector may hinder the effectiveness of the programmes. A project for flood risk reduction is an example of a community-based solution in the Takeo province of Cambodia. One of its activities consists of helping the most vulnerable families to build elevated houses; their small bamboo homes are prone to damage by heavy rains, flooding and strong winds. Similar community-based projects may offer an effective approach for training and capacity building at the community level elsewhere throughout the country.

Lao PDR

Community-based DRR programmes in Lao PDR are implemented through the Village Disaster Prevention Units and the Village Disaster Prevention and Control Committees. They aim to increase awareness among local communities, enabling them to learn actions to be taken before, during and after disasters. The objective of the School Flood Safety Programs, for example, is to enhance the capacity of communities to cope with floods. These programs operate in communities most at risk of flooding. Due to uneven implementation of the DRR strategy across the country, the capacity to manage the risk of disasters varies at the local level. Improving co-ordination and resource allocation from the central level may help meet the challenge.

Myanmar

Myanmar’s 2017 Action Plan on Disaster Risk Reduction acknowledges community-based disaster resilience as a priority action. Since the concept of DRR is relatively new in Myanmar, programmes related to community-based DRR are still limited. Moreover, inadequate financial resources along with lack of institutional arrangement at district or village level have contributed to uneven distribution of community-based DRR programmes. Drought-resilient farming in the dry zone of Myanmar is an example of fruitful DRR in the country. It introduced participatory drought-resistant rice varietal selection in 2014 to strengthen the resilience of subsistence agriculture in this area. Furthermore, access to a wider variety of drought-resilient crops is made possible thanks to the community-level seed banks.

Thailand

Community-based disaster risk management is one of the country’s strategies to improve preparations for mitigating the effects of natural hazards. Despite the relatively solid implementation of the DRR strategy at the national, provincial and community level, the lack of risk information and data sharing hampers the ability of governments to make informed decisions on DRR measures. Further capacity building on the use of technology for government officials, community members and other stakeholders is needed. Several community-based measures have been developed at different localities, such as innovative water solutions in Limthong. For this community, extreme drought during the dry season and severe flooding during the rainy season are the main challenges. The Community Water Resource Management (CWRM) concept was introduced to allow knowledge and technology transfers between villagers and other stakeholders, enabling them to better develop and implement appropriate DRR solutions.

Viet Nam

In Viet Nam, while some projects that adopt top-down approaches might not address local resilience effectively, bottom-up approaches of community-based disaster risk management have shown effectiveness in increasing community awareness. Degradation of the mangrove forest has been a major challenge for Da Loc and Nga Thuy communes. Many DRR projects took place in the area, but local participation was limited. In 2007, a community-based approach for strengthening coastal resilience was introduced. As an institutional output, a Community-Based Mangrove Management Board (CMMB) was formed. With strong support from the local government, the CMMB has mobilised community members to effectively contribute to mangrove restoration and disaster preparedness planning.

Maximising the use of digital tools as an effective early warning system

Advancements in technology create new possibilities to develop low-cost digital tools for early warning systems. These tools could offer better quality and timeliness in transferring information, analysis, monitoring, assessing risk and forecasting, thus allowing better awareness and preparedness against disasters. However, developing countries have a large technological gap in the use of such systems compared to developed countries.

Mobile phones have gained importance in developing countries. In fact, each country in the Mekong region has developed its own early warning phone service. Cambodia has the EWS1294; Myanmar owns a mobile phone application called Disaster Alert Notification; and Thailand brought forward an initiative called Warning Volunteer Networking or Mr. Warning. Early warning systems can also be found in several coastal provinces in Viet Nam. While Lao PDR’s SMS warning system is still in its initial stages, a pilot project has been underway since early 2019. However, despite improvements within the country, the lack of a national early warning system remains an issue.

Addressing water challenges amid the COVID-19 pandemic

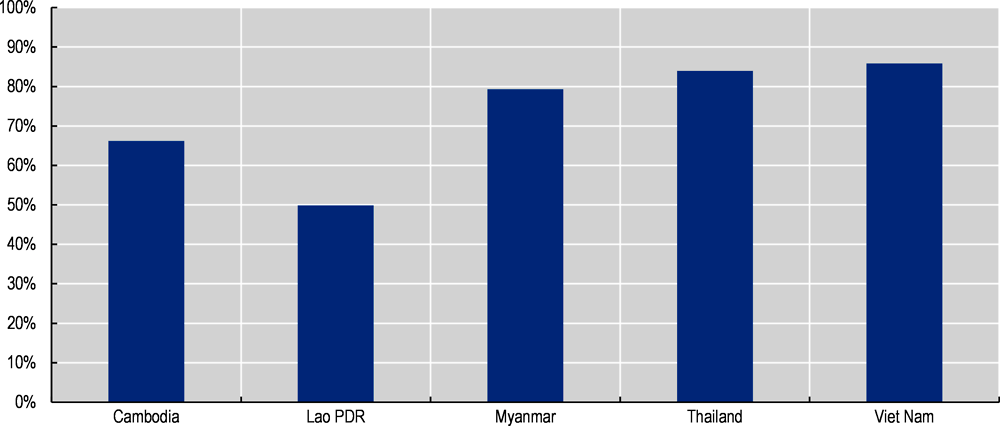

More recently, COVID-19 has been rapidly spreading across the globe. The outbreak highlights the importance of safe and reliable water supply since frequent hand-washing is the most recommended measure to minimise the spread of the virus (OECD, 2020[2]). However, a certain percentage of the population in the region still lacks adequate access to hand-washing facilities with soap and water (Figure 0.3). Improving access to drinking water also remains a challenge, especially for Cambodia, Lao PDR and Myanmar.

Within an urban setting, people living in densely populated areas, especially informal settlements, can also be at greater risk during the COVID-19 and other potential outbreaks. In these areas, physical distancing is nearly impossible, especially at communal water points and sanitation facilities (mostly open pit latrines) where queues often form. These settlements are often not connected to basic services such as piped water, sanitation facilities, and networks for drainage and water treatment. Furthermore, limited household budgets make it difficult to afford access to safe water, and the job losses and economic hardship brought about by the pandemic only serve to exacerbate this issue.

Besides water and sanitation challenges, people living in informal settlements are particularly susceptible to the risk of flooding on a near-daily basis; their settlements are located along rivers, on swamp land or on the riverbed. Disaster preparedness and response plans are often absent, making them even more vulnerable to the effects of flooding. Living conditions, along with daily flooding and other natural hazards, increase the prevalence of vector- and water-borne diseases such as diarrhoea, dysentery, malaria and tuberculosis. These diseases, in turn, reduce immunity and increase the risk of exposure to COVID-19. Thus, addressing unequal access to water is therefore necessary, particularly in densely-populated urban areas.

The COVID-19 outbreak has also affected large-scale infrastructure projects, especially hydropower dam projects along the Mekong River and its tributaries. These projects are at risk of delays and shutdowns due to lockdowns, movement restrictions and fear of contracting the virus among workers. Meanwhile, small-scale projects with dual objectives are emerging. They aim to increase disaster resilience, while dealing with the socio-economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Apart from infrastructure, information regarding guidelines on ensuring safety during the crisis must be disseminated to all communities, especially those not connected to piped water systems and who need to buy water. Mobile phones can also play an important part in raising community awareness and facilitating COVID-19 risk communication. Community leaders may also play an important role in strengthening compliance with basic preventive measures to be applied in other activities that require close contact between people.

Universal access to safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene benefits health, well-being, the economy and the environment. However, the Mekong region faces a number of challenges in these areas. In addition to the need for more financing, co-ordination among actors should improve. Water and wastewater regulators are usually part of a broad regulatory framework at national or sub-national level. These involve different line ministries, local authorities and non-governmental bodies such as consumer advocacy groups or associations of utility professionals. Ensuring strong co-ordination among the different actors is crucial for a smooth implementation of water infrastructure projects.

The water and wastewater services (WWS) sector has several common characteristics and regulators could therefore play a role in ensuring effective water regulations. These include addressing “market failures” in WWS so the sector can fully meet the public interest for all stakeholders at the least cost; promoting easy and transparent access to data; balancing the economic, social and environmental aspects of WWS; ensuring delivery in accordance with the principle of universality, continuity, quality of services, equality of access, affordability and transparency; setting quality standards for drinking water and wastewater treatment to protect public health; and enhancing co-ordination among actors.

Enhancing water and wastewater services regulations in Mekong countries

In the Mekong region, WWS regulations could be much improved, but some challenges remain. Financial sustainability is needed in water tariff regulation. Quality standards for drinking water should be strengthened and laws for wastewater treatment enforced. The region needs to address public service obligations and social regulation, define standards of technical modalities and service delivery, and identify and prevent risk to water availability. Further, it needs to provide incentives in agriculture for more efficient water use, improve private sector involvement, promote innovative technologies through PPP and facilitate initiatives to reduce water demand. It also needs to analyse the investment plans of water utilities, improve information gathering and data collection, and develop the capacity of water operators. Finally, it should strengthen the supervision of contracts with utilities and private actors, monitor utilities’ financing activities, increase public participation, offer consumer protection (including dispute resolution) and address water sector challenges through capacity building.

The five countries in the region may need to address tariffs (which are too low to cover operation and maintenance) (Table 0.2), as well as lack of data, law enforcement, monitoring of services performance and limited human resource capacity. Complex challenges such as governance and financial sustainability are found across the Mekong region with respect to accessing water infrastructure. Addressing these challenges will be critical.

Cambodia

The urban-rural gap is one of the major challenges in water infrastructure in Cambodia. Water systems in rural areas lag behind those of Phnom Penh. Nearly all residents of Phnom Penh have drinking water piped into their dwellings. Elsewhere, less than 60% of residents have piped water. Differences in definitions of terms and policies among jurisdictions have contributed to the gap in drinking water access. Standardising the definitions is therefore essential to improve access. Shortage of physical and human capital, weak law enforcement and credibility of institutions also remain challenging.

Lao PDR

Water conservation is one of the key barriers in Lao PDR. The country does not promote demand management or provide incentives for research and development of conservation technologies. Monitoring of service performance also needs to improve. The reporting structure of water quality is robust. However, reports are written in Lao and highly inaccessible, making it difficult for an external analysis of water quality to be carried out. Responsibilities for funding are delegated to the Water Supply Development Fund, but much of the funding is external. Tax and fee breaks on investment and operation encourage involvement, but poor revenue collection, along with high operating costs, discourage external investment.

Myanmar

In Myanmar, the development and enforcement of quality standards for drinking water are challenges that must be addressed. Efforts are needed to improve institutional efficiency and ensure sufficient infrastructure for wastewater treatment in urban areas. Multiple agencies are involved in wastewater treatment regulation, and inter-agency co-ordination needs improvement. There is also room for further conservation efforts. State-owned irrigation systems do not recover costs, making maintenance or upgrades difficult.

Thailand

Thailand appears to have appropriate water regulation given its legislative challenges. Improvement will be needed in the enforcement of legislation and the development of foreign investment opportunities in the Thai water sector. Water contamination is common due to regulations being ignored. Environmental impact studies of construction projects are only undertaken upon request, putting water supplies at further risk of contamination. Low water tariffs are also a challenge as they have remained mostly unchanged since the 1940s and are far below the amount required to cover operational costs.

Viet Nam

Viet Nam possesses robust water regulations in general. However, more efforts are needed to enforce regulation, monitor service delivery and develop human capital. Licensing and quality standards are in place for wastewater treatment, but most wastewater flows into streams untreated, harming downstream water quality. Water conservation policies exist, but enforcement is far from straightforward, contributing to weak compliance. In addition, as with every other Mekong country for which tariff data are available, tariff schedules struggle to cover operation and maintenance costs.

References

[2] OECD (2020), Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2020 – Update: Meeting the Challenges of COVID-19, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/e8c90b68-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Road and Rail Infrastructure in Asia: Investing in Quality, The Development Dimension, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264302563-en.

[3] WHO-UNICEF (2020), Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (database), https://sdg6data.org/tables (accessed on 13 May 2020).

This document, as well as any data and map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Extracts from publications may be subject to additional disclaimers, which are set out in the complete version of the publication, available at the link provided.

https://doi.org/10.1787/167498ea-en

© OECD/ADBI/Mekong Institute 2020

The use of this work, whether digital or print, is governed by the Terms and Conditions to be found at http://www.oecd.org/termsandconditions.