6. Strengthening multi-level governance and investment capacity to enhance local development in Poland

To enhance local development, Poland needs to consolidate the strategic role of subnational governments in local development. To move in this direction, this chapter assesses how regions and local self-government units (LSGUs) can have the appropriate means to deliver on their responsibilities and maximise public investment returns on regional and local development. The chapter provides key insights for Poland to strengthen its multi-level governance system and promote a functional and territorial approach to regional and local development. The chapter focuses on how to develop a more strategic approach to public investment and ensure strong and fluid partnerships across the national, regional and local levels.

Since 1989, with the restoration of independence and democracy, the Polish multi-level governance system has strongly evolved. After 40 years of centralisation, Poland has pursued political and fiscal decentralisation reforms and the scope and role of subnational governments in policy delivery have increased significantly in the last years. Today, Polish voivodeships and local self-government units (LSGUs) play a crucial role in the definition of their own development as key competencies on regional and local development have been transferred to them. Still, while the role of subnational governments has been progressively strengthened with the decentralisation of new tasks, it is still limited when compared with other OECD regions.

Ensuring a sound multi-level governance system is crucial to make sure voivodeships, counties and municipalities are capable of efficiently promoting regional and local development and continue bridging the investment gap. As recognised by the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government (2019[1]), a multi-level governance approach to investment allows countries to maximise their returns on regional development. Poland has already embarked on improving multi-level relationships focused on strengthening the institutional environment as recognised in the “Strategy for Responsible Development for the period up to 2020 with a perspective up to 2030” (SRD). To move further in this direction, Poland needs to further strengthen the functional and territorial approach to development (see Chapter 1). For this to happen, Poland needs to take better advantage of several existing horizontal co-operation means and embed them with a more comprehensive and function approach. Urban-rural, urban-urban, and rural-rural linkages also need to be reinforced by stronger and more fluid partnerships across levels of government in which top-down processes are combined with bottom-up initiatives. It is also crucial to ensure that voivodeships and LSGUs have the appropriate means to deliver on their responsibilities and reduce the risk of under-funded mandates.

Furthermore, regions and LSGUs play an important role in managing the impact of the COVID-19 crisis, which has led to the first economic recession in Poland since the end of the communist era (see Chapter 1). Indeed, regional and local authorities are responsible for delivering critical short-term measures to this crisis, for example by introducing local tax exemptions, intensifying local procurement for infrastructural projects, reorganising public service delivery, providing sanitary equipment and reorganising education and kindergartens activities, among others. Being responsible for regional and local development, voivodeships and LSGUs will also play a key role in the medium- and long-term recovery, i.e. building more resilient territories that are better able to cope with future crises, whatever their nature. In this context, finetuning the multi-level governance becomes all the more important.

This chapter is based on the findings of the OECD questionnaire developed for this study and responses from national, regional and local actors, as well as evidence collected during four fact-finding missions conducted in different regional and local contexts. The first part of the chapter focuses on the fiscal relation across levels of government as the key framework conditions for an effective multi-level governance system. This first part provides a snapshot of subnational public investment in Poland as the main lever to enhance regional and local development. It also analyses how to ensure a more strategic approach to local public investment. Then, the chapter focuses on the main trends of subnational finance and the ways forward to better align responsibilities with financial means. In order words, it explores how to create the appropriate conditions for subnational governments to deliver on their tasks and ensure their financial capacity to invest. The third part provides some ways forward to facilitate joint actions across LSGUs and promote economies of scale and ways of embedding different LSGU partnerships in a functional and strategic manner. It also focuses on how to improve vertical co-ordination for effective co-operation between different levels of government and how to embed vertical relations with a more bottom-up approach in which LSGUs can take the initiative for investment projects that better respond to local needs.

In OECD countries, regional and local governments play a pivotal role in investing in areas that are critical for growth and well-being. Regions and cities play an increasingly important role in key policy areas linked to infrastructure, sustainable development and citizens’ well-being (e.g. transport, energy, broadband, education, health, housing, water and sanitation). In recent decades, the responsibilities of subnational governments in these fields have increased in a majority of OECD countries. This is also the case in Poland, where voivodeships and LSGUs have been granted increasing responsibilities in regional development investments. Still, as will be detailed in this section, the level of public investment by subnational governments is below the OECD average. Recovering the upward trend of subnational public investment in Poland – especially of infrastructure investments – should be a key priority to enhance regional and local development.

Recovering the upward trend of subnational public investment

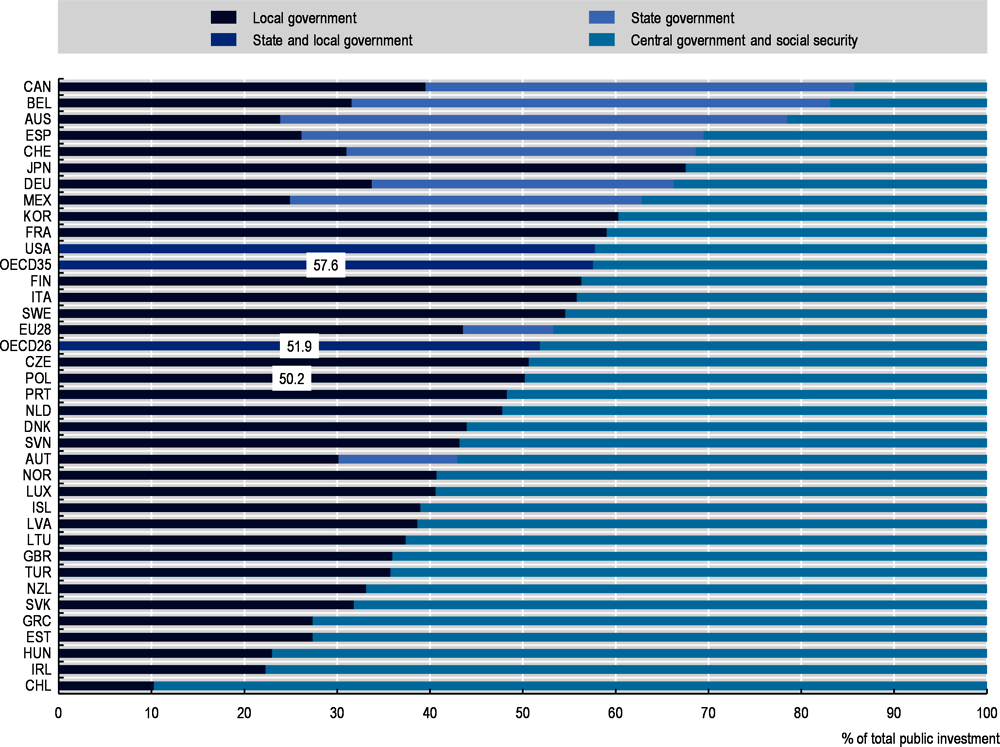

Polish subnational governments are key investors but subnational public investment remains below the OECD average. In 2016, subnational public investment represented 1.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) (1.7%) and 35.7% of total public investment (50.8%), both below the OECD average for unitary countries (OECD, 2020[2]). The 2009 financial crisis put at stake subnational investment. Between 2008 and 2016, subnational investment fell by 5% per year in real terms (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]). Among subnational governments, municipalities are the main investors, carrying out 44% in 2016, while those with county status represent 32% of subnational investment. Counties and regions have an equivalent weight (12% and 13% respectively) (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]).

Some signs show a recent recovery of subnational public investment, especially on infrastructure. Since 2016, subnational public investment, as a share of total public investment, has been recovering from less than 40% to slightly over 50% in 2018, an upward trend driven by municipalities. This is in accordance with the European Investment Bank (EIB) study of subnational infrastructure investment, which shows that over the last 5 years, almost 60% of municipalities in Poland report an increase in investment activities in their jurisdictions and only 9% report a decrease (EIB, 2017[5]). Over the past decade, Poland has significantly improved its infrastructure network, showing particularly a significant upgrade of its transport and energy infrastructure (Goujard, 2016[6]). Although there are discussions about the efficiency of certain projects (aqua parks and airports are the most hotly debated), overall improvement in infrastructure (local roads, sewers, public spaces) during the last years has been significant (Łaszek and Trzeciakowski, 2018[7]).

The improvement of infrastructure investment responds to an important effort by the national level to boost local infrastructure, especially for road investments. Poland stands out among Central European countries with the highest share of own resources (national or subnational) in funding infrastructure investments (EIB, 2017[5]). In Central European countries, the share of EU funds accounts for 25% of total infrastructure funding for municipalities, while this share only reaches 16% in Poland (EIB, 2017[5]). In this effort, the national Local Roads Fund introduced in 2019, for example, which is co-financed by the national and voivodeship levels, has been advantageous for municipalities, allowing them to raise the quality of life of local communities and the attractiveness and accessibility of potential investment. The main objective of this fund is to co-finance the construction, reconstruction and renovation of local roads, which is more important for lower-income municipalities (Box 6.1). Beyond national funding, Poland has also made infrastructure investment a key priority for the 2014-20 European Union (EU) programming period, putting special emphasis on the need to improve transport infrastructure and develop public transport.

In 2019, the Council of Ministers adopted the law creating the Local Roads Fund (FDS) venture, consisting of PLN 6 billion (EUR 1.4 billion) earmarked for the construction of local roads. Funds accumulated in the FDS come, among others, from the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management, the state budgets of the national defence and transport departments, as well as the State Forests National Forest Holding. This fund has replaced the national programme for the development of municipal and county road infrastructure for 2016-19.

The main task of the FDS is to co-finance the construction, reconstruction and renovation of local roads of civil, as well as military importance. The support also concerns the construction of new bridges as a part of the provincial, county and municipal roads. It is estimated that the fund, in 2019, enabled the renovation of 6 000 kilometres of local roads in Poland.

The amount of co-financing from the fund will depend on the income of the LSGU – the lower the income, the higher the co-financing will be, up to 80% of the total cost of one county or municipal tasks.

In 2020, the government announced the plan to transfer a total of PLN 36 billion (EUR 8.5 billion) to LSGUs in the form of FDS grants over the next 10 years. Importantly, multi-year projects will be eligible for FDS support, which could encourage local authorities to undertake larger investments that they have been putting off.

Source: Poland In (2018[8]), “Polish govt to spend billions on local roads”, https://polandin.com/39070710/polish-govt-to-spend-billions-on-local-roads; Construction Market Experts (2019[9]), “Local Roads Fund money allocated among regions – applications to open in days”, https://constructionmarketexperts.com/en/data-and-analysis/local-roads-fund-money-allocated-among-regions-applications-to-open-in-days/; https://archiwum.premier.gov.pl/en/news/news/we-are-developing-the-local-government-roads-fund-in-2021-the-government-is-planning.html

Still, infrastructure investment remains one of the greater challenges for LSGUs

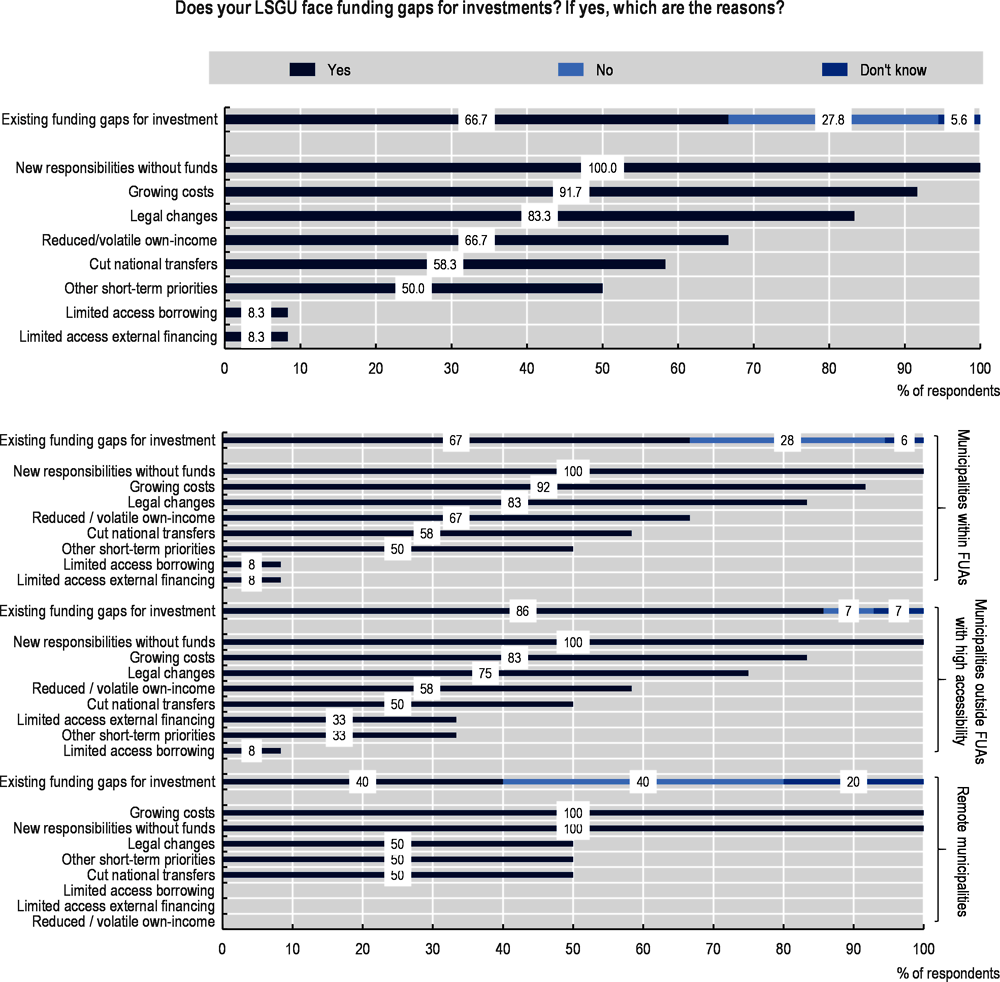

Even if infrastructure investment has been upgraded, evidence shows that a gap between local needs and public investment remains. The EIB study cited above highlights that over the past years, 38% of Polish municipalities believe investment activities in their jurisdiction have been below their needs (2017[5]). This perceived gap stands out in urban transport for which 43% of municipalities report an investment gap (compared to 35% at the EU level), as well as in social housing and environment (EIB, 2017[5]). The OECD questionnaire conducted for this report also shows this gap between needs and actual public investment at the local level – 70% of respondents declared having a funding gap for investment, mainly due to the assignment of responsibilities without the corresponding funds (see section above) and the growing costs of existing services. This investment gap has been reported to be more pronounced in LSGUs inside functional urban areas (FUAs) than in remote ones (Figure 6.2). This is also the case at the national level where, for example, the perceived quality of overall transport infrastructure and electricity supply remains lower than in most OECD countries (Goujard, 2016[6]).

Accessibility and the quality of roads is still a key priority for all types of LSGU across Poland. The quality of roads varies across the country: municipal roads exhibit the greatest share of unpaved roads (54.8% in 2017), in comparison with the county (8% of soil roads) and regional roads (0.1%) (see Chapter 1). Moreover, 26 out of the 73 TL3 regions1 (including counties) have more than 50% of their road network unsurfaced (see Chapter 1). During the OECD missions to different LSGUs, all of them mentioned the need to put greater efforts into road infrastructure to improve their citizens’ well-being as well as connectivity with the different economic centres within and outside the country. In Ziębice, for example, stakeholders reported having poor road infrastructure and street lighting, making the municipality less attractive for large investors. This is particularly relevant for local self-governments as all LSGUs across Poland are encouraged to attract businesses and offer better conditions for investment.

The current COVID-19 pandemic puts at stake infrastructure investments for all levels of government. All countries face the risk of using public investment as an adjustment variable, as was the case after 2010 to counterbalance fiscal consolidation plans that had created a strong drop in public investment, as observed in EU and OECD countries until recently (Box 6.2) (OECD, 2020[10]). In order to reduce these risks, the Polish national government has been very reactive in mitigating the negative impact of the crisis. Since March 2020, it has put in place a recovery package of EUR 48 billion, i.e. almost 10% of the Polish GDP. The package has 5 thematic pillars including one dedicated to boosting public investment by EUR 6.6 billion. The government will establish a special fund to finance public investment in the construction of local roads, digitalisation, modernisation of schools, energy transformation, environmental protection and reconstruction of public infrastructure (OECD, 2020[10]).

In order to ensure the level of public investment and make it a key tool for crisis exit and recovery, it will be crucial that public investment contributes to resilience and a low carbon economy. For this, all levels of government need to integrate social and climate objectives into recovery plans. To make the most of public investment in this context, as developed in the next sections, strengthening the multi-level governance system will be crucial.

Many national and subnational governments have reacted quickly to address the economic and fiscal consequences of the crisis and countries are spending significantly more than in 2008-09. A number of countries have already announced recovery strategies with a focus on public investment to support economic recovery in the short and medium terms.

The level of public and private investment in OECD countries prior to the COVID-19 crisis was still below the 2008 pre-crisis levels. A main risk in the current context is a further decline of subnational public investment, which would act as a procyclical effect impeding the recovery. In several countries, the risk is high, given the contraction of self-financing capacities and increasing deficits. It is also important to avoid large investment stimulus followed by very strong fiscal consolidation, a sequence seen in 2008-10 that undermined public investment for almost a decade.

Experience from the 2008 financial crisis indicates that investment recovery strategies need to be well-targeted to a few priority areas and that the way public investment strategies are managed largely determines their outcomes, as highlighted by the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government. During the implementation of investment recovery packages in 2008-09, for example, a major challenge came from the fact that investment was fragmented by the municipality, thus limiting the potential for large projects with an impact on territorial development.

Recovery investment strategies need to be aligned with ambitious policies to tackle climate change and environmental damage. Technologically advanced, sustainable and resilient infrastructure can pave the way for an inclusive post-COVID economic recovery (World Economic Forum, 2020[11]). It is also essential to look beyond physical infrastructure investment and consider investment needs in skills development, innovation and research and development (R&D). It is particularly important to ensure that investments from stimulus packages do not impose large stranded asset costs on the economy in coming decades.

Some key recommendations developed by the OECD to ensure that public investment can contribute to the crisis exit and recovery are:

Minimise fragmentation in the allocation of funds and ensure allocation criteria are guided by strategic regional priorities.

Consider temporarily relaxing fiscal rules to create sufficient fiscal space for public investment.

Consider introducing green and resilience-building criteria for the allocation of public investment funding for all levels of government.

Help target public investment strategies to green and inclusive priorities by introducing conditionalities.

Encourage regional and local authorities to invest in digital infrastructure with an eye on full territorial coverage and ensure adequate weight is given to regional digital inclusion in support of public investment choices.

Source: OECD (2020[10]), “The territorial impact of COVID-19: Managing the crisis across levels of government”, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=128_128287-5agkkojaaa&title=The-territorial-impact-of-covid-19-managing-the-crisis-across-levels-of-government.

In Poland, as in most OECD countries, the alignment of responsibilities and revenues remains an area of concern for LSGUs. As will be discussed in details in this section, the mismatch between revenue-generating means and the responsibilities that have been recently assigned to LSGUs affects their capacity to effectively deliver on their mandates. To ensure that LSGUs are capable of promoting local development and financing investments, it is crucial to make sure they have adequate funding. In this respect, reducing the mismatch between expenditure and revenue generation means LSGUs should be a priority for Poland.

Municipalities have led the increase of subnational expenditures

Polish subnational governments, especially LSGUs, are key economic and social actors. The share of subnational governments2 expenditure in total public expenditure substantially increased with decentralisation reforms (see introduction), going from 23% in 1995 to 34.4% in 2018 (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]; OECD, forthcoming[4]). Regional and municipal expenditures as a share of public expenditure (34.4%) and GDP (14.3%) (Figure 6.3) in 2018 were above the OECD average for unitary countries (28.6% and 12% respectively) and similar to the EU average (33.7% and 15.4% respectively), even if they remain below the average for all OECD countries (40.5% and 16.2% respectively). Polish municipalities have also increased their municipal spending autonomy during the last years. A recent study by the OECD shows that, between 2011 and 2017, municipal spending autonomy3 in Poland has increased by more than 5% in contrast with other countries such as the Czech Republic, Estonia or Spain where spending autonomy has decreased (Moisio, forthcoming[12]).

While municipal expenditure has been increasing, the role of regions is still limited. Indeed, while looking at subnational expenditure, municipalities are by far the ones that expend the most. In 2016, municipalities were responsible for more than 80% of subnational expenditure (48% for municipalities and 35% for the cities with county status) (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]) and county expenditure represented 11%. Regions were only responsible for 5.3% of subnational expenditure, contrasting with 25% on average in OECD unitary countries (OECD, 2020[13]). For regions, the most important share of expenditure is dedicated to economic affairs (52%) while only 5% and 7% of their expenditure goes to education and health respectively (OECD, 2020[13]).

The primary spending area of Polish counties and municipalities is education. In 2016, subnational expenditure in education (considering voivodeships, counties and municipalities) accounted for 48% of total public expenditure (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]). Subnational governments are responsible for both capital and current expenditure, including remuneration of teachers and staff, which represent one of the most important subnational expenditure items not only in Poland but also for a large part of OECD countries. Thus, it is not surprising that the last reforms on transferring more responsibilities to municipalities regarding education have put strong pressure on municipal budgets. One key issue regarding the recent changes to the education law is that LSGUs have a limited capacity to adapt the school network and infrastructure to the sometimes-decreasing number of students. As the amount of the educational subsidy is calculated on the basis of the number of students, without a change in the network of educational institutions, LSGUs, to a large extent, have to finance the education task from other funds.

Social protection and healthcare, being the second and third most important subnational expenditure items, put Polish subnational governments at special risk in the current COVID-19 crisis. Social protection expenditure has substantially increased in recent years, becoming the second most important subnational budget item in 2016 (21% vs. 13% in 2013) (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]). In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, subnational governments are confronted with a number of complex and costly tasks. They must first manage the full or partial closure of certain services and facilities, and then the reopening to ensure the continuity of essential public services. They also need to adjust the services either physically (public transport, collection of waste, cleaning of public spaces) or virtually (telehealth consultations, remote education arrangement, local tax payments, access to government information, etc.) (OECD, 2020[10]).

Reducing the mismatch between expenditure and revenue-generating means

Subnational governments rely particularly on national government transfers

Subnational governments – voivodeships, counties and municipalities – in Poland are highly dependent on national government grants and subsidies, which represent almost 60% of subnational revenues, above the OECD average of 37% and the OECD average for unitary countries of 50% (Figure 6.4). In 2016, grants and subsidies represented 65% of county revenues, 56% of municipal revenues and 47% of regional revenues. In contrast, municipalities with county status have a more diversified structure of revenue, with grants and subsidies representing only 38% of their revenues (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]). Revenue autonomy (own revenue relative to total resources available) at the local level is lower than the EU average (41% vs. 53% in 2018), which indicates a higher-than-EU-average dependency on national government transfers (59% vs. 48% in 2018) (CoR, n.d.[14]). Mirroring the expenditure side, the grant to cover educational expenses, including teachers’ salaries, is by far the largest (78% of the general grant) accounting for 17% of subnational governments’ revenues in 2016 (OECD/UCLG, 2019[3]).

Voivodeships and counties highly rely on national government’s transfers or EU funding. Regional revenues represent a very small share of total subnational revenues (5.5%) and tax margins for regions are also low (1.5% of the income tax of physical entities, 0.5% of corporate tax) (OECD, 2020[13]). The majority of regional funds comes from mostly pre-allocated national state endowments, while most regional expenditure is quasi-obligatory (health and education) (OECD, 2020[15]). Voivodeships receive a portion of shared tax revenue, according to a fixed percentage, being the ones that receive the largest share of corporate income tax. Counties also receive a share of national income taxes but do not have any other form of tax revenue, which limits their investment capacity. Moreover, for some LSGUs that heavily rely on national or EU funding, the strategic planning process could be particularly challenging: with funding being assigned on a project basis, some LSGUs may tend to prioritise projects based on availability rather than other higher strategic priorities (OECD, 2018[16]).

Municipalities are the only subnational tier (of all three levels) that hold the power to tax – though this power is limited. LSGUs in Poland collect less revenue from autonomous taxes and more from tax-sharing schemes than in the rest of OECD countries. The LSGU tax autonomy indicator by the European Committee of the Regions (CoR) shows that LSGUs in Poland have very low autonomy in setting rates related to their tax revenues: the biggest share relates to shared taxes (59%), while 30.1% of the total is tax revenues over which LSGUs have little to no autonomy (CoR, n.d.[14]). The majority of local taxes are set by national laws or regulations and local authorities can only introduce some tax exemptions and reliefs. The only exception is the tax rate of property tax. Indeed, for municipalities, property tax is the most important local tax levied on buildings and plots of land. The amount of local taxes and fees is determined by each municipality but must comply with frameworks and upper tax limits determined by national legislation. Property tax revenue accounted for 28% of total budget revenues for predominantly rural subregions, 25% for intermediate subregions and 17% for predominantly urban ones in 2014 (OECD, 2018[16]). These figures have changed little since 2010 (OECD, 2018[16]). In contrast, counties do not have any lever to determine any local tax variable.

Poland is thus among the countries with a higher vertical fiscal gap4 at the municipal level (Figure 6.5). In contrast with countries such as Estonia or Malta where over 80% of municipal sector spending is financed with national government transfers, in Poland, this rate reaches 57%. Still, the vertical fiscal gap in Poland is more important than in other OECD countries such as Chile or Estonia, the last being one of the most centralised countries in the OECD.

Municipalities receive the largest share of the personal income tax transfer and as such, are encouraged to attract people to live in their territory (Box 6.3). Still, Polish localities have a very limited ability to incentivise their citizens to pay the personal income taxes in order to increase their tax sharing revenue. The same happens with general grants, notably the education grant, which is calculated based on the number of pupils and teachers in a county. To prevent a reduction of education grants, some counties strives to hold on to their populations. Jarocin, for example, a town in central Poland, attempts to do this by collaborating with the national government to provide subsidised housing (Łaszek and Trzeciakowski, 2018[7]). The recent improvement of the road infrastructure network (see Chapter 1) has had a two-sided effect on tax collection in this regard. On the one hand, it has improved the accessibility of medium and small cities to FUA centres, with the positive implications on economic growth that this generates (see Chapter 1). On the other hand, it has indirectly encouraged people to move to less densely populated areas and smaller towns. In turn, this has benefitted some cities that now collect more local taxes but others with a declining population need to resort to more innovative ways of funding to counteract the decline of local tax collection.

The fiscal capacity of municipalities varies significantly across Poland depending on their size and income sources. To address these disparities, Poland has adopted a number of vertical and horizontal equalisation systems. The general subsidy for municipalities from the state budget consists of three parts: i) an educational subsidy calculated on the basis of the number of students in schools and educational institutions under the competency of the municipality; ii) a “compensation” or equalising part in which municipalities with fiscal revenues of less than 90% of the national average receive additional funds; and iii) the “balancing” part from a horizontal equalisation mechanism where municipalities obtaining the highest tax income per inhabitant make contributions to the mechanism and the funds are redistributed on the basis of an algorithm including different criteria (see Box 6.3).

The limited fiscal flexibility of Polish subnational governments might be a risk factor to face the current COVID-19 crisis. The crisis has resulted in increased expenditure and reduced revenue for subnational governments and, while its impact on subnational finance will not be uniform across the country, it is expected to be long-lasting. Polish subnational governments, depending strongly on national grants, might in the short term be less exposed to revenue impacts than other subnational governments in OECD countries such as Canada or Sweden. Still, it is expected that, in the medium term, the decrease in revenues, combined with a continuous increase in expenditure (due to social spending and investment), could result in a scissor effect and therefore in subnational government deficit, as was the case in 2007-08 (OECD, 2020[10]).

Given the high fixed expenditures that municipalities, counties and voivodeships have, they have limited ability to absorb exceptional stress and restricted capacity to adjust their expenditure and revenues to urgent needs. Preliminary estimates show that some LSGUs might experience a negative gross operating surplus (difference between current income and current expenditure); for other LSGUs, the surplus might be less than 2% (Cieślak-Wróblewska, 2020[17]). Both situations imply an important adjustment for LSGUs, both in current expenses as well as in local investments and maintenance. LSGUs across Poland are already making efforts to reduce expenses or increase revenue sources. Drawsko, for example, has made cuts in investment expenditure by nearly PLN 11 million; the city council of Grudziądz has adopted resolutions to increase the price of public transport tickets and real estate tax, as well as expand the paid parking zone (Cieślak-Wróblewska, 2020[17]).

Subnational government revenues in Poland come mainly from four sources:

1. Own-source tax revenues levied through limited taxation powers in accordance with nationally determined maximum rates.

3. Grants, including general-purpose grants and conditional (or earmarked) grants. The latter may include resources from EU budgets (Structural and Cohesion Funds).

4. Non-tax own-source revenues (user tariffs and fees; revenue from property, leasing and sales, including revenues from municipal companies and public utilities).

Property tax is the most important tax for municipalities, which are the only ones that hold the power to tax. The amount of the local taxes and fees is determined by each municipality but must comply with frameworks (and upper tax limits) determined by national legislation. Property tax rates are differentiated depending on the purpose of the property, including the basic division that applies to residential and commercial properties. For example, in the case of land, property tax is based on the area of the land (to a maximum of PLN 0.89/m² of land); in the case of buildings, it is based on their floor area (to a maximum of PLN 23.03/m² of the usable surface of a building) (Ernst & Young, 2014[18]). This information is determined through the national registry and assessment takes place on an annual basis. Only one element of property tax is based on assessed value: certain construction structures (other than buildings) that are being used in economic activity are taxed based on the market value at a fixed rate (usually 2% of market value). Agricultural and forestry lands are subject to taxes, which are separate from property taxes. Other taxes that are far more marginal to the municipal budget include taxes on agricultural lands (paid by hectare with soil quality taken into account), forests, large vehicles and a number of other minor duties.

Shared tax revenue comes from the share of personal income tax (48% of subnational tax revenue) and company income tax (9% of subnational tax revenue). Shares of national income taxes are redistributed to all three levels of subnational government according to a fixed percentage of the total proceeds collected within the territory of the jurisdiction with municipalities receiving the largest share of the personal income tax transfer and voivodeships receiving the largest share of corporate income tax. As such, there is a fiscal incentive for municipalities to increase their populations and for voivodeships to foster business growth. There is no horizontal equalisation mechanism.

The general-purpose grant consists of four main shares: education, equalisation, balancing and regional. Despite these delineations, subnational governments can spend general grants at their own discretion – they are not tied to a particular purpose (with the exception of the part of the educational subsidy allocated to expenditure on educating children with special educational needs).

1. The education share accounts for over 20% of subnational government revenues. It covers educational expenses, including teacher’s salaries.

2. The equalisation share (5% of subnational revenue) is allocated to all subnational governments with below-average tax capacities. Municipalities whose per capita revenue-raising capacity from local and shared revenues are below that of a national threshold amount qualify for a basic grant determined on the basis of both population and tax capacity. The structure of the equalisation grant favours small municipalities with low population density (Sauer, 2013[19]).

3. The balancing share (only for municipalities and counties) distributes funds based on social expenditure; it takes into account such issues as GDP per capita, the surface area of public roads per capita and the unemployment rate in an area.

4. The regional share is a general grant calculated for each region based on the unemployment rate, GDP per capita, area of public roads per capita and regional railways expenditure.

In addition to the above, some municipalities may also receive “compensation” grants, which are used to compensate municipalities for lost property tax revenues due to special economic zones (special zones that can be established which provide businesses with income tax rebates, hence limiting tax intake for the municipality).

The final group of conditional or earmarked grants are related to the responsibilities that have been delegated to LSGUs, the most important of these being provisions for social assistance. The vast majority of intergovernmental transfers in Poland are lump sums as opposed to matching grants. Grants from the EU are included under conditional or earmarked grants in most cases. The value of LSGU revenue to GDP ratio in Poland has been significantly higher than the average of EU countries (Uryszek, 2013[20]).

The 2015 Revitalisation Act expands municipal fiscal instruments on two points: i) it enables LSGUs to calculate and collect an adjacency levy (at a rate higher than that set by general rules), which can be used to capture the increase in value of real estate as a result of the construction of municipal infrastructure in the regeneration zone; ii) it introduces the possibility of increasing the real estate tax rate (up to PLN 3/m² of land per year) in the designated revitalisation zone for new developments.

Source: OECD (2018[16]), OECD Rural Policy Reviews: Poland 2018, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264289925-en; OECD (2016[21]), Governance of Land Use in Poland: The Case of Lodz, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260597-en; Uryszek, T. (2013[20]), “Financial management of local governments in Poland-selected problems”, https://doi.org/10.7763/JOEBM.2013.V1.55; Ernst & Young (2014[18]), The Polish Real Estate Guide: Edition 2014 - The Real State of Real Estate, http://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY_Real_Estate_Guide_Book_2014/$FILE/EY_Real_Estate_Guide_Book_2014.pdf; Sauer (2013[19]), “The System of the Local SelfGovernments in Poland”, Research paper 6/2013, Association for International Affairs, https://www.amo.cz/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/amocz-RP-2013-6.pdf.

Strengthening revenue-generating means, aligning LSGU responsibilities and revenues

One of the most important challenges for Polish municipalities relies on the existence of underfunded or unfunded LSGU responsibilities, as in many OECD countries. As mentioned above, with decentralisation reforms, municipalities have been granted more responsibilities over the last years and the access to EU funds has increased their competencies. While municipalities are in a better position in terms of own-source revenue than counties and voivodeships, it is often remarked that they have seen more responsibilities devolved to them and yet very little in the way of increased fiscal decentralisation to match it. Successive OECD reviews have made this point (OECD, 2009[22]; 2013[23]; 2018[16]). The alignment of responsibilities and revenues remains an area of concern in most OECD countries as subnational expenditure far exceeds subnational tax revenues. This vertical fiscal gap is often filled by other sources of revenue, e.g. non-tax revenues and transfers (OECD, 2019[24]).

The recent educational reform seems to put strong pressure on some municipalities’ financing and their ability to predict funding. The 2017 national educational reforms to the primary and secondary education system of primary and secondary schools place significant costs linked to infrastructure and teachers’ salaries on municipalities, in particular the smaller and remote ones. For example, LSGUs reported that they sometimes need to use their own budgets to cover the costs of retrofitting classrooms or severance payable to exempted teachers (Wojniak and Majorek, 2018[25]). Since September 2017, students attend eight years of primary school and four years of secondary school (or five years of vocational school); middle school enrolments will be phased out and municipalities are obliged to provide pre-primary education for each child. For this to be possible, LSGUs have to bear the costs of new infrastructure but without adequate funding. This particularly affects rural and remote municipalities.

The assignment of responsibilities without the corresponding funds seems to be one of the major reasons behind investment funding gaps at the local level. During the OECD visit to different LSGUs across Poland all relevant actors identified the lack of financing of new responsibilities on education as a key challenge for the efficient management of expenditure and investments. The OECD questionnaire also reveals that all municipalities facing a funding gap for investment identify the existence of unfunded mandates as the main reason explaining this gap, and this is the case for all types of municipalities, whether inside FUAs, outside, or remote (Figure 6.2). The lack of funding and resources is also identified as the top challenge for all types of municipality to fulfil the responsibilities that are assigned by law. In addition, as seen in the recent OECD field visits to different municipalities and as pointed by previous OECD studies (2018[16]), municipalities report facing unpredictable funding due to changes related to the structure of significant factors in education subventions. A particular concern for rural municipalities is the timeframe for determining educational subventions on a year-to-year basis. More upfront communications on these changes will help communities better plan (OECD, 2018[16]).

The mismatch between responsibilities and revenues makes Polish voivodeships and municipalities very dependent on European funding, in particular for public investment. EU funds have greatly contributed to accelerating the development of Poland. They have allowed, for example, LSGUs to undertake infrastructure investments that have shaped the local reality and that would have not been possible without access to this source of funding. While subnational governments should continue to make the most of EU funding opportunities, they also need to diversify their sources of financing for public investment in a proactive way and not to rely too much on external funds as the only source of funding. At the same time, European co-financing may favour voivodeships and municipalities that have higher administrative and institutional capacities in preparing projects to be funded by European funds. To reduce these inequalities, voivodeships play a critical role in supporting LSGUs to strengthen their capacities to develop projects able to be financed by EU funds. The role of voivodeships in encouraging joint projects, through integrated territorial investments (ITIs) to implement EU projects across several jurisdictions for example, is also crucial.

A better balance between revenue-generating means and expenditure needs might help Poland in creating better accountability and responsiveness. Further decentralising revenues, by granting larger tax autonomy to LSGUs in Poland, may ensure more efficient functioning of the decentralisation system. Poland has space to expand the autonomous tax revenue. Indeed, evidence shows that subnational governments work best when local residents self-finance local services through local taxes and charges. This enhances the efficiency and accountability of local service provision by encouraging local residents to evaluate the costs and benefits of local service provision (OECD, 2019[24]).

To maximise public investment returns on regional development, it is important to strengthen the Polish multi-level governance system. For this, moving towards a functional approach to the different partnerships between LSGUs is crucial. At the same time, Poland needs to embed vertical relations between the national, regional and local self-governments with a more bottom-up approach in which LSGUs can take the initiative for investment projects that better respond to local needs.

This is particularly relevant in the current COVID-19 crisis, as Poland needs to develop the right means to implement efficiently the COVID-19 crisis recovery package. At the same time, in order to protect public investment and make it a key tool for crisis exit and recovery, it will be crucial that public investment contributes to resilience and a low-carbon economy. For this, all levels of government should integrate social and climate objectives into recovery plans. In order to make the most of public investment in this context, as developed in detail in this section, strengthening the multi-level governance system is crucial.

As recognised by the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government (Box 6.4), a multi-level governance approach to investment allows countries to maximise their returns on regional development. National governments can help ensure a balanced approach to infrastructure development and regional and local actors are well placed to prioritise needs and identify complementarities at the local level. Better aligning investment with spatial and land use planning, as well as ensuring a functional approach to investments are key ways forward for Poland. For this, it is crucial to move towards an approach through which the different partnerships between LSGUs are developed in a functional and strategic fashion to optimise investment. At the same time, Poland needs to embed vertical relations among the national, regional and local governments with a more bottom-up approach in which LSGUs can take the initiative for investment projects that better respond to local needs.

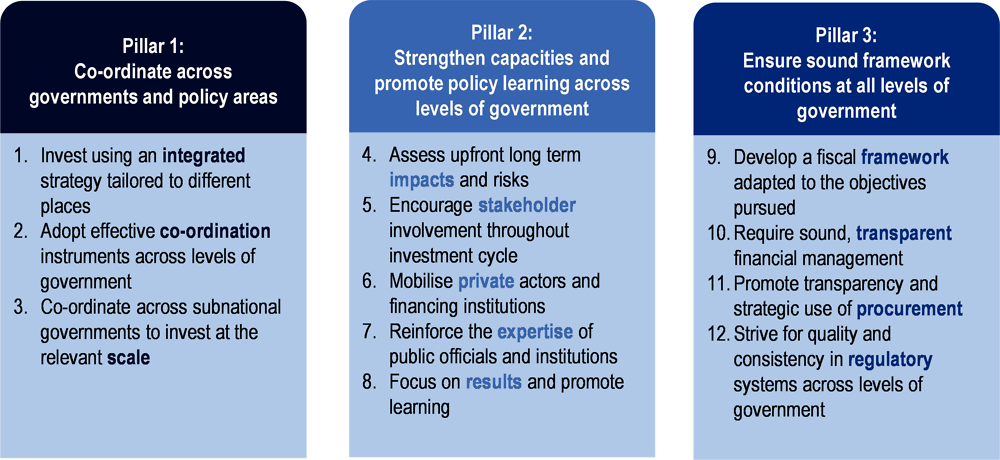

In 2014, the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government was endorsed by the OECD Regional Development Policy Committee (RDPC) and adopted by the OECD Council. The recommendation aims to help countries assess the strengths and weaknesses of their public investment governance capacity for regional development across all levels of government. It serves as a guide to setting priorities for improving the co-ordination mechanisms and capacities of subnational governments in the management of public investment.

The recommendation sets out 12 principles grouped into 3 pillars of policy recommendations that represent 3 systematic challenges to efficiently managing public investment at both the national and subnational levels. These 12 principles cannot be seen in isolation. The principles offer a whole-of-government approach that addresses the roles of different levels of government in the design and implementation of a critical and shared responsibility. All the principles are complementary and there is no hierarchy among them. They are also intended to be used in conjunction with other OECD policy guidance and tools.

Poland has already embarked on improving multi-level relationships focused on strengthening the institutional environment. The SRD (see Chapter 3) recognises the need to strengthen the institutional environment in Poland. The strategy identifies a variety of institutional challenges such as weak social capital in some voivodeships that inhibits the collective action needed for locally based development activity. The SRD also points to the need for reducing the rigid control exercised by the national level over the actions of subsidiary governments, thereby preventing innovative activities as well as the need to reduce excessive reliance on EU funds and EU programmes to define public policies.

The SRD also shows an increased awareness of the need to strengthen multi-level governance by reaffirming the commitment to decentralisation. The strategy explicitly highlights the need to reinforce co-ordination mechanisms between levels of government. Several efforts support this, including territorial contracts, Regional Social Dialogue Councils and a Joint of National Government and Local Self-Government (Joint Committee). This committee has established a forum to determine a common national government and LSGU position on state policy towards self-governments, as well as issues concerning LSGUs within the scope of action of EU and international organisations (OECD, 2018[16]). The forum has shown the commitment to a multi-level approach to policy design by developing joint opinions on legislation, programme documents and policies that have the potential to impact LSGUs, including their finances. The Social Dialogue Council, which provides a dialogue forum between the national government and the 16 regional councils, is another example of this commitment.

Moving towards a comprehensive and functional approach to inter-municipality co-operation

Co-ordination and collaboration among municipalities are particularly relevant in the Polish dispersed settlement structure. Poland has a large number of small- and medium-sized cities that are broadly distributed across its territory that provide essential services to non-metropolitan regions. Essentially, urban and rural areas are engaged in a symbiotic relationship where collaboration can benefit both places (OECD, 2018[16]). But conversely, competition between adjacent urban and rural places also tends to weaken both. This makes strong horizontal co-operation among LSGUs crucial. Partnerships among municipalities allow managing fragmentation by sharing infrastructure and co-delivering services between large cities and surrounding communities, which can help enhance quality of life across the country.

Many OECD countries have recently enacted regulations to encourage this type of collaboration, which varies in the degree of co-operation, from the lightest (e.g. single or multi-purpose co-operative agreements) to the strongest form of integration (e.g. supra-municipal authorities with delegated functions and even taxation powers) (OECD, 2017[26]). While the purposes of the associations can vary, inter-municipal co-operation arrangements allow internalising externalities in the management of services and benefitting from economies of scale for utility services (water, waste, energy, etc.), transport infrastructure and telecommunications. Inter-municipal co-operation can result in investments that would not be pursued if subnational governments were not collaborating and in services provided more efficiently, as underlined by the first pillar of the OECD Recommendation on Effective Public Investment Across Levels of Government.

It is important for LSGUs to make greater use of the different forms and mechanisms for inter-municipal co-ordination. More flexibility, less red tape, as well as a stronger role in developing incentives for such co-ordination from the voivodeship and national levels, are needed to ensure that municipalities have the right mechanisms in place and the knowledge to act.

Polish law foresees different forms of inter-municipal co-operation

Inter-municipal co-operation has been at the core of the Polish multi-level governance system since the first wave of decentralisation reforms. Regional self-governments and LSGUs have made active use of the right to associate provided in the constitution (Article 172.1). Currently, there are six active associations of local and regional authorities with national coverage,5 which play an active role in the representation, defence and advancement of local interests, conducting regular negotiations with the national government. The Municipal Self-Government Act of 1990 also lists in details all the constitutionally guaranteed possibilities to deliver public tasks. The act states that municipalities can co-operate in the form of unions of municipalities as single or multi-purpose public law entities (inter-municipal registered associations), inter-municipal public law agreements and associations of LSGUs as private law entities. Municipalities can also set up and act together in public law companies (Table 6.1) (Kołsut, 2016[27]; Potkanski, 2016[28]).

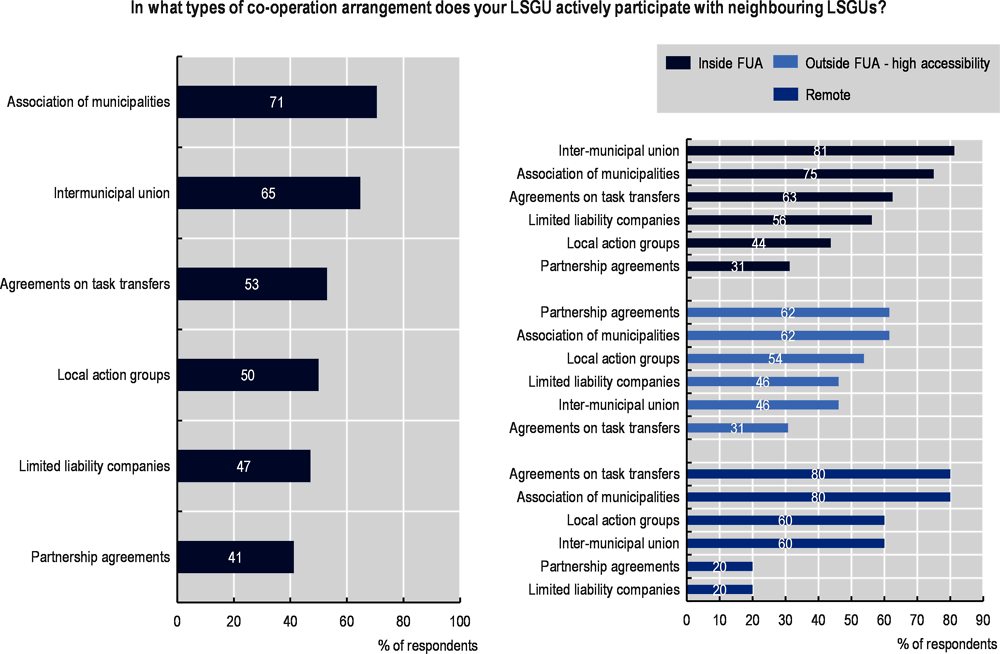

Polish LSGUs are increasingly recognising the benefits of inter-municipal co-operation. The two most used forms of co-operation are inter-municipal unions and inter-municipal agreements. Among the municipalities responding to the OECD questionnaire for this report, 71% declare participating in an association of municipalities, 65% in an inter-municipal union and 53% in an agreement on task transfers (Figure 6.7). Municipalities inside FUAs are the ones that make the greater use of inter-municipal unions and agreements, followed by municipalities outside FUAs with high accessibility. In turn, remote municipalities6 are the ones that make greater use of agreements to transfer tasks to other municipalities. With these responses, it seems that municipalities are increasingly recognising the need to co-operate when they are part of the same FUA. At the same time, remote municipalities have fewer capacities to deliver certain services and thus make greater use of the possibility of transferring certain tasks to other municipalities, although this finding is based on a limited sample of remote municipalities.

The access of Poland to the EU has also had a strong influence on strengthening co-operation arrangements for regional and local development, as it is a core element of EU Cohesion Policy. By forming unions, municipalities have been able to apply for pre-accession funds that were too large for municipalities to receive individually. This is the case, for example, of the Union of the Upper Raba Communities and Kraków that was created to deal with water degradation in the Raba River basin (Council of Europe, 2010[29]). Inter-municipal co-operation for waste management is also a clear example of the benefits brought by the EU membership. The term “waste revolution” is commonly used in Poland to describe institutional changes resulting from the adjustment of domestic law to EU requirements (Kołsut, 2016[27]). The increasing tendency of co-operation for waste management between Polish municipalities has been also reinforced by a large stream of EU funds earmarked for waste management projects (Kołsut, 2016[27]). In addition, Poland has had a successful experience with integrated territorial investments (ITIs), which have strengthened, among others, rural-urban partnerships by tackling joint projects across functionally connected municipalities. A key issue in the implementation of ITIs is the degree of formalisation of partnerships that can influence the quality of strategic programming. In Poland, the co-operation of municipalities in the development and governance of FUAs seems to be the most important element for efficient ITI functioning. ITIs in Poland have effectively promoted co-operation between different administrative units at the functional urban level. They have served, so far, as a laboratory of inter-municipal co-operation. Looking forward, the maintenance of flexibility of activities, without imposing artificial boundaries of the area of intervention, seems to be of key importance in the scope of governance of ITI implementation in the future.

For the 2014-20 EU Cohesion Policy, ITIs allows EU member states to bundle funding from several Priority Axes of one or more operational programmes (EU programmes) to ensure the implementation of an integrated strategy for a specific territory. This tool responds to the necessity to strengthen the integrated approach to development programming combining policies, sectors and funds.

In Poland, ITIs are in place since 2012 – they are compulsory for the FUAs of voivodeship capitals. They are also optional in nine selected FUAs of regional centres and FUAs of subregional centres. The conditions to implement an ITI include:

The establishment of an ITI union can take the form of an arrangement of self-governments, an association or an intner-municipal union.

The ITI union overtakes the tasks related to the implementation of the national or regional operational programme that have been so far the responsibility of regional authorities, which means that regions cease to be the only entities and partners for the government’s regional policy.

In the majority of cases, the establishment of ITI unions was based on two models: i) an “interim” model, usually taking the form of an arrangement, in which LSGUs established an ITI union for the purpose of expending allocations from a Regional Operational Programme (ROP); and ii) the “co-operation” model, where the ITI union is a natural continuation of previously commenced co-operation.

The preparation of an ITI strategy that specifies: the diagnosis of the area of implementation of an ITI together with the analysis of developmental challenges; the objectives to be implemented in the scope of an ITI; expected results and indicators related to the implementation of the ROP; proposals of project selection criteria in the course of an open call for proposals; a preliminary list of projects selected in the restricted call for proposals; and the sources of financing.

The establishment of an arrangement or agreement concerning ITI implementation between an ITI union and the relevant governing institution of the ROP.

Source: Kociuba, D. (2018[30]), “Implementation of integrated territorial investments in Poland – Rationale, results, and recommendations”, https://doi.org/10.2478/quageo-2018-0038.

The voluntary nature of ITIs leads to collaboration on projects that are mutually beneficial (OECD, 2018[16]). The Partnership City Initiative is an experience inspired by European examples that also reflects efforts carried out at the national level to strengthen networks of municipalities and that could be further developed (Box 6.6).

The aim of the Partnership City Initiative (PCI) is to improve development conditions and support the integrated and sustainable development of Polish cities. It is an element of the SRD. For this, the Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy (MDFRP) provides organisational (e.g. organising meetings) and expert support for the networks. So far, 3 networks have been launched – air quality, urban mobility and revitalisation – with 34 cities involved. The representatives of individual LSGUs, responsible for the given topic, as well as external experts, participate in the works of each network.

All cities, in addition to exchanging experiences, work on the so-called Urban Action Initiatives, which are documents containing specific solutions for previously identified challenges and/or local problems. The final result of the work of each network will be the Improvement Plan, which is a document containing a set of recommendations for conducting national policies related to the thematic area of a given network.

Source: Ministry of Investment and Economic Development (2019[31]), Sustainable Urban Development in Poland, https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/media/72570/raport_en_final.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2020).

Inter-municipal co-operation schemes have been used in Poland for several purposes, most of them linked to investments in local roads or public transport, the delivery of public services such as waste management or the joint management of sewerage systems. Inter-municipal unions have also been adopted to promote investment in such areas as the agri-food sector or the development of tourism, sport and leisure (OECD, 2018[16]). For example, diverse groups of municipalities have set up public transport unions. Some of them date from the early stages of decentralisation reforms, such as the Municipal Transport Association of the Upper Silesian Industrial Basin created in 1991 in the Katowice metropolitan area – which is the largest and most densely urbanised region in Poland. There are also more recent unions established such as the Sub-Radom Automotive Transport Union of Municipalities dating from 2010 (World Bank, 2016[32]). During the OECD field research, different municipalities also declared co-operating with their neighbours for specific projects or services. The municipality of Łubianka, for example, collaborates with other municipalities for waste treatment, environmental protection and health protection. Kutno also collaborates with its neighbours in the provision of kindergartens by supporting their infrastructure in other smaller municipalities. Some co-operation between neighbouring municipalities also occurs informally, such as the case of Międzyrzec Podlaski where the urban and rural municipalities conduct regular meetings in order to align priorities without having a formal agreement or co-operation framework.

Still,the take-up of the different forms of inter-municipal co-operation remains slow

While increasing, the take-up of the different forms of inter-municipal co-operation remains slow and differs across the country. The EIB study that focuses on infrastructure investment shows that only 23% of Polish municipalities co-ordinate their investment projects with other neighbouring municipalities (compared with 37% on average in the EU) and only 17% do so with a network of municipalities, the smallest share of all EU countries represented in the study (EIB, 2017[5]). While inter-municipal co-operation is increasingly popular in areas such as water and waste management or broadband and road infrastructure, it remains limited in sectors such as education and housing (OECD, 2018[16]). Moreover, a study focusing on co-operation in waste management shows that the spatial distribution of inter-municipal bodies is uneven and clearly differs by voivodeship, co-operation in northern and western Poland being more important than in the south and east (Kołsut, 2016[27]). The author calls this a “voivodeship factor” as the regions play a significant role in initiating and stimulating co-operative behaviour among municipalities (Kołsut, 2016[27]).

Currently, co-operation between municipalities is mainly done on a project basis, lacking a comprehensive functional approach to co-operation. In general, co-operation takes place for particular investment projects or the delivery of certain services for which municipalities see an advantage in acting together. This is the case of road building, waste management services or public transport agreements. When it comes to strategic planning, municipalities only consult their own local development or spatial strategies with other neighbouring municipalities but do not necessarily plan together with the functional area in mind (see Chapter 3). An important change in this respect has been introduced by amendment to the Principles of Development Policy Act as of July 2020, which introduced the possibility of developing supra-local strategies by LSGUs pertaining to the same functional area (see Chapter 3). This represents an important step forward towards a functional approach to strategic planning, one that considers the whole territory and not only the administrative boundaries. The development of specific instruments to implement such strategies, with their corresponding incentives, would allow municipalities to have a comprehensive and territorial approach to development. The county, voivodeship and national levels play a crucial role in encouraging such an approach.

A key challenge for establishing co-operative arrangements in Poland is the lack of financial resources and incentives whereby municipalities could access higher or other funding sources if they plan together to conduct joint projects or share services. In the OECD questionnaire for this study, the lack of financial resources to form a co-operation arrangement and the lack of incentives appear as two major challenges for the majority of municipalities of all types. Interestingly, for remote municipalities, the lack of understanding of functional links with their neighbours is the primary challenge when it comes to horizontal co-ordination, in contrast with other municipalities (in FUAs or outside FUAs with high accessibility) for which this challenge appears only in the eighth or ninth place (Figure 6.8). Several stakeholders from the voivodeship and LSGU levels during the OECD field research also highlighted that co-operation was facilitated when they were able to access more funding. The lack of resources for municipal associations’ or unions’ joint projects may indeed explain the failure of some that were created in the early stages of decentralisation reforms. Due to a lack of incentives from co-operative arrangements between different municipalities, their creation depends largely on the political will and personal contacts of local authorities.

Excessive and complicated administrative procedures also hamper co-operative arrangements in Poland (Figure 6.8). A clear example is the burden caused by administrative procedures when municipalities want to integrate their public transport offer. When municipalities collaborate for public transport, they meet a number of legal obstacles making such integration difficult and expensive; rules are extremely detailed and suggest that agreeing on integrated fares across operators within a FUA is also unduly complex (World Bank, 2016[32]). Moreover, it is common to observe that while some co-operative agreements are set up, they stop functioning due mainly to administrative procedures that impede their efficient functioning. This is the case, for example, of the energy cluster started by Ziębice with other municipalities that did not receive the appropriate certification to prosper. The slow uptake of such agreements may be also in part due to a lack of adequate knowledge about how they work and the risks involved (OECD, 2018[16]). The lack of concrete incentives coupled with bureaucratic procedures results in weak co-operation between municipalities.

Encouraging municipalities to form inter-municipal co-operation schemes

Further developing financial incentives for co-operative arrangements between municipalities is crucial for their greater success. Through financial incentives, Poland can encourage joint planning and the delivery of joint services, which is particularly relevant to face common local challenges, such as the ageing population (see Chapter 1) and attenuate increasing costs of services. Many OECD countries have recently passed regulations to encourage inter-municipal co-operation on a voluntary basis. For instance, France offers special grants and a special tax regime in some cases and other countries, like Estonia and Norway, provide additional funds for joint public investments. Slovenia introduced a financial incentive in 2005 to encourage inter-municipal co-operation by reimbursing 50% of staff costs of joint management bodies – leading to a notable rise in the number of such entities. In Galicia, Spain, investment projects that involve several municipalities get priority for regional funds (Mizell and Allain-Dupré, 2013[33]; OECD, 2019[1]). Inspired by these examples, Poland can envisage assigning a share of existing funds for local development and investments exclusively to joint projects. Alternatively, Poland can further develop the territorial contracts for projects between the national or regional self-governments and municipal unions or associations. The county level can also play an active role in encouraging co-operation through financial incentives since the planning phase. For this, examples such as the one of Lubelskie, which provides additional funding for municipalities of the functional area that prepare a joint strategic plan, could be further expanded.

Peer learning and the creation of capacities are also crucial processes to further encourage municipalities to co-ordinate planning, investments and service delivery. Given the spatial compactness and closeness of co-operative arrangements in Poland for some areas such as waste management, diffusion and imitation seem to be key elements for their success (Kołsut, 2016[27]). Some OECD countries have opted to encourage collaboration by providing consulting and technical assistance, promoting information sharing or providing specific guidelines on how to manage such collaboration. Arrangements to solve capacity issues have been popular in particular among the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) but they have also been practiced in Chile, France, Italy and Spain for example (OECD, 2017[26]; 2019[34]).

Most of the time, inter-municipal co-operation is promoted on a voluntary basis. Incentives are created to enhance inter-municipal dialogue and networking, information sharing and sometimes to help in the creation of these entities. These incentives can be financial or can also have a more practical nature (consulting and technical assistance, production of guidelines, measures promoting information sharing such as in Canada, Norway and the United States). Several countries have also implemented new types of contracts and partnership agreements to encourage inter-municipal co-operation.

France has more than 36 000 communes, the basic unit of local governance. Although many are too small to be efficient, France has long resisted mergers. Instead, the national government has encouraged municipal co-operation. There are about 2 145 inter-municipal structures with own-source tax revenues aimed at facilitating horizontal co-operation; 99.8% of communes are involved in them. Each grouping of communes constitutes a “public establishment for inter-municipal co-operation” (EPCI). EPCIs assume limited, specialised and exclusive powers transferred to them by member communes. They are governed by delegates of municipal councils and must be approved by the state to exist legally. To encourage municipalities to form an EPCI, the national government provides a basic grant plus an “inter-municipality grant” to preclude competition on tax rates among participating municipalities. EPCIs draw on budgetary contributions from member communes and/or their own tax revenues.

In Slovenia, inter-municipal co-operation has risen in recent years, in particular with projects that require a large number of users. In 2005, amendments to the Financing of Municipalities Act provided financial incentives for joint municipal administration by offering national co-financing arrangements: 50% of the joint management bodies’ staff costs are reimbursed by the national government to the municipality during the next fiscal period. The result has been an increase in municipal participation in such entities from 9 joint management bodies in 2005 to 42 today, exploding to 177 municipalities. The most frequently performed tasks are inspection (waste management, roads, space, etc.), municipal warden service, physical planning and internal audit.

At the sub-regional level in Italy, there is a long tradition of horizontal co-operation among municipalities, which takes the form of Unione di Comuni, intermediary institutions grouping adjoining municipalities to reach critical mass, reduce expenditure and improve the provision of public services. A law from April 2014 established new financial incentives for municipal mergers and unions of municipalities. Functions to be carried out in co-operation include all the basic functions of municipalities. All municipalities up to 5 000 inhabitants are obliged to participate in the associated exercise of fundamental functions.

The Autonomous Community of Galicia in Spain has many small municipalities. Many have limited institutional capacity and are spread out geographically, which increases the cost of providing public services. The regional government has taken steps to encourage economies of scale. First, it has improved the flexibility of and provided financial incentives for voluntary (“soft”) inter-municipal co-ordination arrangements. Investment projects that involve several municipalities get priority for regional funds. “Soft” inter-municipal agreements tend to be popular in the water sector. Local co-operation is also being encouraged in the urban mobility plan for public transport, involving the seven largest cities in the region. The regional government also imposed a “hard” co-ordination arrangement. Specifically, it created the Metropolitan Area of Vigo, an association of 14 municipalities. Although the metropolitan area was defined by the regional government, it was based on a history of “light co-operation” among 12 municipalities (out of 14). Voluntary municipal mergers may be encouraged in the future.

Source: OECD (2020[35]), Regional Policy for Greece Post-2020, OECD Territorial Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cedf09a5-en; OECD (n.d.[36]), Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government Toolkit, www.oecd.org/effective-public-investment-toolkit; OECD (2017[37]), Gaps and Governance Standards of Public Infrastructure in Chile: Infrastructure Governance Review, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264278875-en.

In Chile for example, where the culture of collaboration between municipalities is weak, municipal associations have had a positive impact on investments and capacity building. Municipalities that are part of an association in Chile have proven to develop better investment projects able to get financing, to positively affect capacities of smaller municipalities, and to have more bargaining power than municipalities on their own to get financing from regional and national levels (OECD, 2017[38]). Based on these OECD experiences, Polish municipalities with successful stories can share their experience and encourage other municipalities to enter into such arrangements by showing that, through partnerships, municipalities can achieve more efficient and better results. Voivodeships and counties could lead this capacity building and peer learning process, in particular regarding weaker and rural municipalities. They are the ones that can organise peer learning, offer technical support and act as political facilitators. The elaboration of a clear toolbox or guidelines on how to deal with the administrative procedures when establishing co-operative arrangements should accompany this process.

Association of municipalities of Chile (Asociación Chilena de Municipalidades)

The Association of Municipalities in Chile’s objective is to represent all Chilean municipalities, defend their interests and promote bottom-up policies. Its mission is “To be a democratic institution, representative and leader of all Chilean municipalities fulfilling a role of promotion of innovation and excellence, through education, training as well as technical and political support with the aim to deepen the decentralisation of the state”. The association also acts as an expertise centre and think tank. It has already published a number of studies, surveys and publications that cover different topics such as municipal health, public education, citizen security, child protection, e-commerce, staff management, electoral participation, migration, transport and good municipal practices, among others. In 2017, the Association of municipalities of Chile comprises 61 municipality members.

Association of Chilean Municipalities (Asociación de Municipalidades de Chile)

The Association of Chilean Municipalities is a national-level body bringing together 342 of Chile’s 345 local authorities (membership is voluntary). One of its objectives is to strengthen municipal capacity among both elected officials (mayors, municipal council members) and municipal civil servants who participate in a variety of seminars, training courses, workshops and fora. The association develops information products and training on legislative and regulatory updates. It also comprises technical commissions made up of mayors and municipal council members that explore specific areas in municipal management, such as housing, health, education, finance, staff management and the environment. The association also promotes the execution of joint development strategies among municipalities.

Source: OECD (2017[38]), Making Decentralisation Work in Chile: Towards Stronger Municipalities, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279049-en.

More flexible co-operative arrangements may also be needed to spark municipal co-operation, in particular to face uncertainty and address the current crisis challenges. The existence of rigid legal forms of co-operation in Poland is among the top five challenges highlighted by all type of municipalities in the OECD questionnaire, being more prominent for municipalities inside FUAs. Indeed, the flexibility of co-operative arrangements is particularly relevant for municipalities pertaining to different functional areas that face specific and distinct challenges. France’s “reciprocity contacts” are a good example of how a country can structure dialogue between municipalities but does not rigidly fix the responsibilities of each party. The purpose of this approach is to develop a framework for mutual exchange that can support the accompanying project (OECD, 2018[16]) (Box 6.9). The flexibility of co-operative arrangements is also crucial to allow municipalities to react more efficiently and quickly to the challenges which have arisen due to an unexpected crisis such as the current pandemic, which differ markedly across a country’s territory. Facilitating inter-municipal co-operation can support recovery strategies by ensuring coherent safety/mitigation guidelines, pooling resources and strengthening investment opportunities through joint procurement or joint borrowing. The importance of such co-operation has been seen in Denmark, for example, where municipalities have joined forces to purchase protective equipment for their personnel. In Sweden, the four largest municipalities have joined forces with a guarantee for a credit of half a billion for the purchase of protective equipment for all Swedish municipalities (OECD, 2020[10]).

Well-aware of the complementarity potential of its different urban and rural territories, France has developed a new experimental tool to promote inter-municipal collaboration: city-countryside reciprocity contracts (contrats de réciprocité ville-campagne).

These agreements are adaptable to different territorial realities; their jurisdictions are not predefined, which allows them to cover different areas depending on the issue at hand. The process is primarily led at the inter-municipal level, with the state, regions and departments being asked to support local initiatives.

France’s reciprocity contracts acknowledge the diversity of rural areas and seek to strengthen and valorise urban-rural linkages. This is driven by an understanding that urban-rural interactions should address not just proximity issues (e.g. commuting patterns) but also consider reciprocal exchanges in order to build meaningful partnerships. Potential areas for co-operation include:

Environmental and energy transition (e.g. waste management, food security, the preservation of agricultural land and natural areas, and bioenergy development).

Economic development (e.g. the joint promotion of the territory and the development of joint territorial strategies, land use policies, support for businesses and the development of teleworking to help maintain remote towns centres).

The quality of services (e.g. promoting tourist sites, access to sports facilities, leisure, heritage and access to health services).

Administrative organisation (e.g. mobilisation of staff with specific skills to support key projects or needs.

Source: OECD (2018[16]), OECD Rural Policy Reviews: Poland 2018, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264289925-en.

Moving forward with the governance of metropolitan areas

Co-ordination across municipalities is particularly relevant in metropolitan areas. Suitable governance arrangements in urban areas can promote productivity (Ahrend et al., 2014[39]). Enhancing the co-operation and co-ordination of the provision of public infrastructure and services on a metropolitan scale can also improve the quality of life and international competitiveness of large cities.