Chapter 2. Design and delivery of Latvia’s labour market policies

This chapter provides overviews of both active and passive labour market policies in Latvia. First, it presents the set of active labour market policies available to jobseekers. Second, it provides a brief description of the social benefits system and its possible implications for work incentives. The chapter then reviews the activities of the main actors involved in the design and implementation of labour market policies and most importantly of the State Employment Agency (SEA) and municipalities. Special attention is given to the SEA’s engagement with jobseekers and employers, the role of caseworkers and the co-operation between the SEA and municipalities.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Active labour market policies

This chapter presents a detailed overview of the system of labour market policies in Latvia. It describes the main measures, discusses a range of practical issues in the delivery of policies, and provides new analyses where statistics were thus far unavailable. After giving an overview of Latvia’s active labour market policies (ALMP), the chapter proceeds to passive labour market policies, i.e. benefit schemes. It then turns to how labour market policies are designed and implemented. Notable institutional actors are Latvia’s public employment service, the State Employment Agency (SEA), as well as municipalities.

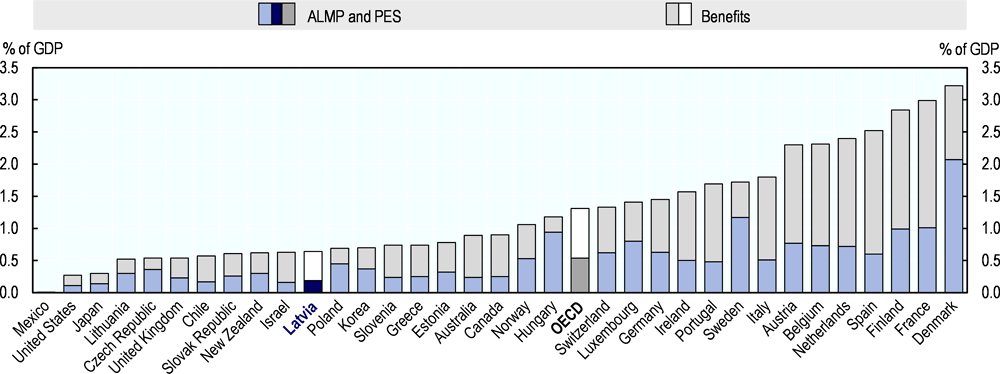

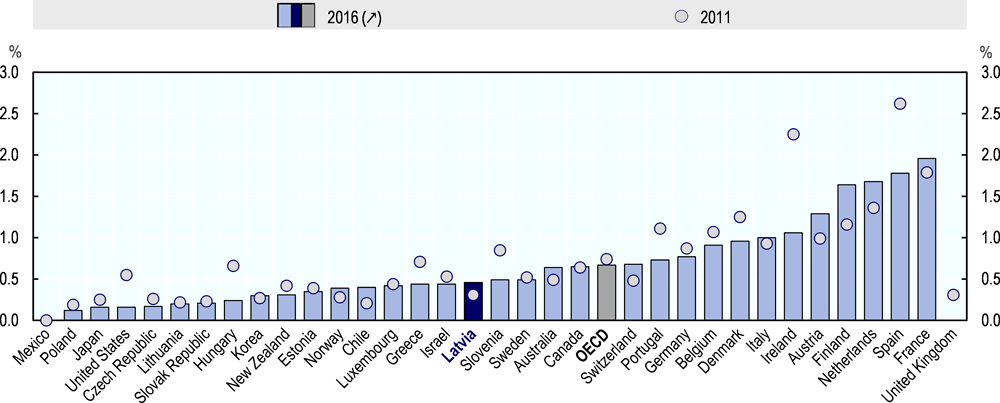

Overall, ALMP in Latvia receive little public spending in comparison to other OECD countries (Figure 2.1). In 2016, expenditures in Latvia were equivalent to 0.19% of GDP, representing the sixth-lowest ALMP budget among OECD countries. On average, OECD countries devoted 0.53% of GDP to ALMP. These figures include all expenditures on the PES, although such expenditures are not only generated by ALMP. At 0.45% of GDP, expenditures on passive labour market policies were not as low in comparison to other OECD countries, but still well below the OECD average (0.77%).

While most OECD countries spent more on benefits than on ALMP, the imbalance was especially strong in Latvia: expenditure on benefits was more than twice as high as expenditure on ALMP (Figure 2.1). Substantially higher ratios – around three times the expenditure on ALMP – were only observed in Australia, Israel and Spain. At 1.4, the average ratio for OECD countries was considerably lower. Latvia’s spending on ALMP therefore appears low not only in comparison to other OECD countries, but also in comparison to the expenditure on benefits.

Participation in active labour market policies is very low in Latvia

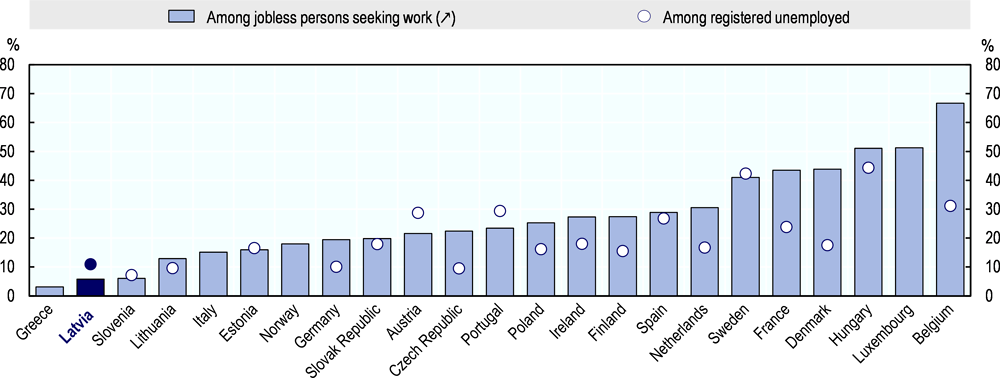

Low expenditure on ALMP in Latvia is reflected by low participation of unemployed persons in ALMP measures. Figure 2.2 shows participants among all unemployed and the registered unemployed. The two measures can differ significantly, but both indicate Latvia as having one of the lowest participation in ALMP among the European OECD countries: in 2016, only 11% of the registered unemployed in Latvia and less than 6% of jobless persons who seek work participated in ALMP. While figures were only somewhat higher for Estonia and Lithuania, participants there accounted for 10% and 17% of the registered unemployed, respectively, and for 13% and 16% of jobless persons who seek work. In Poland, one-quarter of jobless persons who seek work participated in ALMP, and this proportion rises to two-thirds in Belgium. In this context, short training measures and workshops e.g. on job search skills are not counted as ALMP. Enlarging the use of ALMP has become one of the primary objectives of Latvia’s Inclusive Employment Strategy 2015-2020 (Box 2.1), especially with regards to disadvantaged groups on the labour market, such as long-term unemployed, persons with disabilities, older workers and jobseekers under 25.

Latvia’s Inclusive Employment Strategy 2015-2020 was announced in August 2014 at an inter-ministerial meeting of State Secretaries, was subsequently approved by the cabinet and has since been implemented under the auspices of the Ministry of Welfare. The funds for the implementation of the Strategy are largely provided by the European Union, notably through the European Social Fund (ESF).

Three overarching policy objectives are formulated in the Inclusive Employment Strategy (Ministry of Welfare, 2015[2]). The first is to make Latvia’s labour market more inclusive by reducing barriers to the employment of disadvantaged jobseekers, including long-term unemployed, persons with disabilities, youth and older workers. Specific policy goals under this heading include: extending and better targeting ALMP, increased use of career counselling, promoting regional labour mobility, raising participation rates in groups with a high risk of unemployment and fostering social entrepreneurship. The concrete efforts towards these goals include improved profiling of unemployed persons, closer co-operation between the SEA and the municipal social services to focus on long-term unemployed persons and recipients of social assistance, implementation of the Youth Guarantee and development of an active ageing strategy.

The second overarching goal is bringing labour supply and demand in Latvia more into balance. The specific goals under this heading include greater availability and precision of information on the labour market, effective training of unemployed persons, promoting entrepreneurship among the unemployed and fostering improvements in the quality of jobs. One of the concrete efforts towards these goals is the collection of labour market information from various sources on a single platform used for monitoring and forecasting. The third overarching policy objective is the creation of an institutional environment that is conducive to employment, with the specific goal to develop a system of taxes and benefits that favours employment, also of disadvantaged jobseekers.

While most policy goals of the Inclusive Employment Strategy are not formulated in quantifiable terms, explicit targets have been set in relation to long-term unemployment (Ministry of Welfare, 2015[2]): by 2020, the long-term unemployed should not represent more than 15% of all unemployed persons and not more than 2.5% of the labour force. In early 2013, long-term unemployed represented 54% of all unemployed, according to the Latvian Labour Force Survey. This share has since fallen to 44% in early 2015 and 38% in early 2017. The long-term unemployed also still represented more than 4% of the labour force in 2016 (see Chapter 1). The ambitious targets of the Inclusive Employment Strategy for the reduction of long-term unemployment may therefore prove difficult to reach by 2020.

Progress towards the goals of the Inclusive Employment Strategy has recently been made with the introduction of a preventive programme to prolong the employment of older workers, the first creation of a legal framework for social enterprises in Latvia, and with significant amendments to tax legislation that are set to reduce the tax wedge for labour income. A reform of Latvia’s policies towards persons with disabilities is in preparation and might well include changes for ALMP. A mid-term review of the Inclusive Employment Strategy will be undertaken over the course of 2019 and several policies pursued may be adapted accordingly in scale and scope.

Recently introduced ALMP programmes focus on disadvantaged groups

Latvia’s menu of ALMP has expanded in recent years. Table 2.1 shows how numbers of participants in the various programmes have evolved since 2012. Introduced in 2013, a programme promoting jobseekers’ mobility across Latvian regions has since grown substantially. Programmes introduced in the following years focus throughout on disadvantaged groups on Latvia’s labour market. Several programmes were set up in 2014 specifically for young persons (ages 15-29) in the context of the Youth Guarantee – the commitment of EU Member States to offer every young person either employment or education within four months of leaving school or becoming unemployed. In 2016, a programme was set-up for the motivation and rehabilitation of long-term unemployed as well as unemployed with disabilities or addiction problems. The most recent programme started in 2017 with the aim of preventing unemployment of older workers by raising their skills and promoting active ageing strategies in firms.

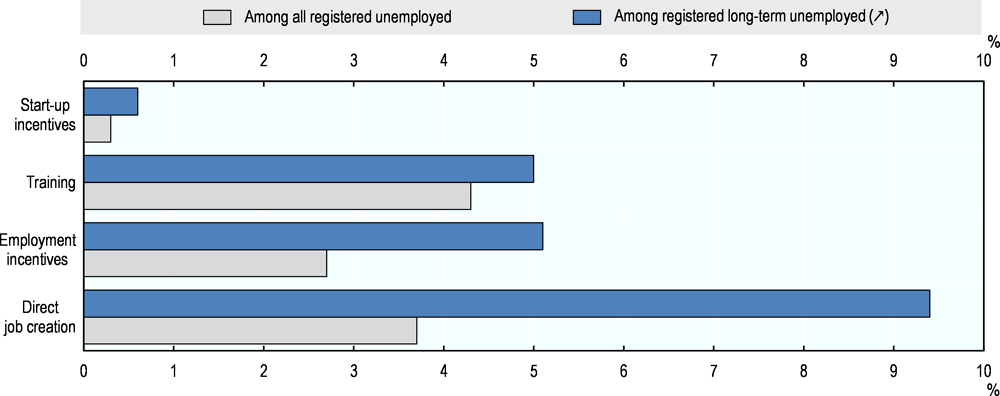

Registered long-term unemployed in Latvia are more likely than other registered unemployed to be included in measures of ALMP (Figure 2.3). Using the grouping of ALMP programmes indicated in Table 2.1, the largest difference arises for direct job creation measures (above all Latvia’s public works programme): more than 9% of registered long-term unemployed participated in such measures in 2016, compared with little 4% of all registered unemployed. Long-term unemployed were also substantially overrepresented in measures for employment incentives. In total, one in five registered long-term unemployed (14%) participated in ALMP measures in 2016, close to twice the share of all registered unemployed.

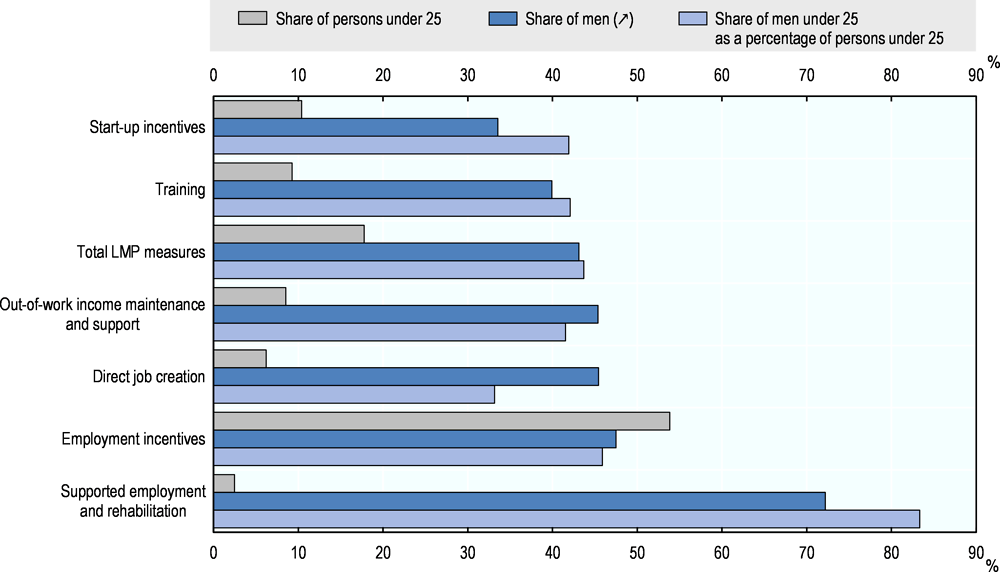

In most kinds of measures, men accounted for around 40% of new participants (Figure 2.4). But they made up 72% in supported employment or rehabilitation. As this kind of ALMP is often used in the context of long-term unemployment, the predominance of male participants likely reflects that men make up a large majority of the long-term unemployed (see Chapter 1). Their share is especially large (83%) among persons under 25 in supported employment or rehabilitation. By contrast, in direct job creation, men accounted for a substantially lower share among persons under 25 (33%) than among all new participants (45%). In most kinds of ALMP measures, however, men’s share of new participants under 25 closely corresponded to men’s share of all new participants, which makes it unlikely that participants in ALMP measures were somehow selected with a gender bias: any such bias would have had to be applied consistently across age groups. Instead, it appears likely that the gender distribution among participants reflects the gender distribution among unemployed persons who are eligible for a given kind of ALMP.

Next, this chapter briefly describes the ALMP programmes, grouped as in Table 2.1 with the exception that the large number of labour market services are not counted towards ALMP. Delivered by the SEA in group sessions or individually, these services provide career counselling and address certain basic competencies of jobseekers. Career counselling is intended to offer advice on education and training, occupational choice and professional development based on the jobseeker’s interests and abilities. Measures for basic competencies seek to help jobseekers navigate the labour market in Latvia and abroad, notably through short courses in job search skills such as writing CVs and performing in interviews.

Training is largely provided through vouchers

The largest group of ALMP programmes, representing one-fifth of all participants in ALMP in 2018, provide some form of training (Table 2.1). More than 4 000 participants in 2018 were involved in vocational training that leads to either a formal professional qualification (following an examination) or a certificate for professional skills. The length of the course normally ranges from 160 to 320 hours for a certificate and from 480 to 1 280 hours for a formal professional qualification, so that a course can require 6 months in full-time education. In 2016, participants had most frequently enrolled in social care (about 900 participants), office administration (500), project management and welding (400 each), as reported in SEA (2017[3]). A programme for non-formal training involved more than three times as many participants as the programme for vocational training (about 14 000 in 2018) but the length of these courses was limited to 60-160 hours. Such courses often cover languages, IT skills or driving. The most frequent non-formal courses in 2016 were in basic IT skills (2 100), advanced IT skills (1 400), and English at elementary level (1 200). However, altogether 2 200 participants also took courses in the Latvian language at various levels of proficiency.

Both vocational and non-formal training courses are allocated through a voucher system. The vouchers specify the kind of training that they are valid for, and their face value reflects the length of the training. Courses may be offered by accredited private or public training providers. In a number of OECD countries, vouchers have been used in the context of adult training, mainly because they allow for a certain freedom of choice and because they can induce competition between training providers. However, it has also been observed that low-skilled jobseekers tend to benefit less: using the voucher and finding an effective training provider may depend, for example, on intrinsic motivation, existing related skills, or the person’s location. Weber (2008[4]) and Barnow (2009[5]) offer observations on the role of vouchers in ALMP in Austria and the United States, respectively.

Registered unemployed are eligible for training essentially whenever additional training is needed to place them in a job. This is assessed on an individual basis but with the help of a profiling tool discussed below. Participation in vocational training therefore includes both jobseekers with qualifications that are outdated or no longer demanded and those who have never gained a professional qualification. Especially vocational training provided under the Youth Guarantee represents a second chance for young persons to obtain a professional qualification at all, and courses may take up to nine months in their case. A detailed discussion of training programmes and an analysis of the extent to which different kinds of training have helped the unemployed in Latvia to find employment are included in Chapter 3.

Comparatively small training programmes offer workshops for young persons or training at the (future) employer. The workshops allow young persons who lack qualifications or work experience to explore between one and three occupations in vocational schools for some weeks, while receiving a monthly allowance of EUR 60, or EUR 90 in the case of persons with disabilities. Training at the employer is an option when an employer offers a job for a very specific skill set. If the employer arranges for the necessary training of a registered unemployed person and commits to employing this person for at least 6 months after the training phase, the SEA can cover parts of the salary for the first 6 months.

Programmes that support life-long learning were part of Latvia’s ALMP until 2014 but have since been organised under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education and Science. The current programme targets employed persons with a low skill level and older workers. Vocational training including formal qualifications is available through the programme, as well as career counselling and the certification of professional competencies. The selected participants only have to bear 10% of the training costs. In 2017, close to 13 000 persons were supported under the programme.

A shift from public works to employment incentives and rehabilitation

Two programmes targeting long-term unemployed persons or those in need of some form of rehabilitation accounted for more than half of all participants in ALMP in 2018. A special activation programme for the long-term unemployed was only introduced in 2016 but involved 3 700 participants in its first year and jumped to 54 000 in both 2017 and 2018 (Table 2.1). This programme takes a holistic approach to persons who have been unemployed for 12 months or more, persons with disabilities who have not worked for 12 months or more, and persons with addiction problems. It arranges for career counselling as well as psychological support sessions, assessments of mental and physical health, mentoring and motivation courses. The latter are not conducted by the SEA but by other service providers and may be combined with paid work experience from four to 12 weeks. During the motivation course, participants receive a tax-free stipend of EUR 150 per month. The comparatively small but longstanding Minnesota programme is addressed specifically at unemployed persons with addiction problems. Within 28 days, external service providers (registered medical institutions) guide participants through 12 steps designed to treat addiction to alcohol or other drugs. The programme covers the costs of treatment and accommodation.

Direct job creation takes place in Latvia’s programme for temporary public works. This programme, adapted from an earlier programme in 2009, has provided support to a large number of unemployed who had exhausted their unemployment benefits (Strokova and Damerau, 2013[6]). It still had more than 30 000 participants in both 2011 and 2012, then decreased to 9 000 participants in 2015. Numbers have since recovered somewhat and exceeded 13 000 in 2018, which represented 14% of all participants in ALMP (Table 2.1). The programme arranges for non-market jobs that are specifically created by municipalities or non-profit organisations. This includes repair and maintenance work on local infrastructure and auxiliary tasks in social care or municipal services such as schools and kindergartens. According to SEA (2017[3]), 3 000 such jobs were created in 2016, half of them in Latgale alone. They could nevertheless serve more than 10 000 participants because participation is limited to four months in every 12 months. Registered unemployed are eligible if they have been unemployed for at least 6 months or have not held a job for at least 12 months. They earn a monthly remuneration of EUR 150 and their social security contributions are paid by the programme. Another programme classified as direct job creation is only available under the Youth Guarantee and supports young persons who work in NGOs with a monthly allowance of EUR 90 for up to 6 months. This is intended to provide them with work experience at an early stage.

For some of the most vulnerable groups of unemployed – long-term unemployed, persons with disabilities and those aged 55 or above – a programme is available (partly offered under the Youth Guarantee) that subsidises their employment for longer time periods, up to 12 months but up to 24 months in some cases, notably for persons with disabilities. When an unemployed person from any of these groups is hired, the subsidised employment programme can reimburse half of the total wage costs to the employer, albeit not more than the legal minimum wage or 1.5 times the legal minimum wage in the case of persons with disabilities. In addition, expenses for adapting workplaces can be covered, and mentoring is provided in some cases. Chapter 5 empirically evaluates the impact of this programme.

While around 1 500 persons participate each year in subsidised employment for the most vulnerable groups (except in 2018, when about 1 000 participated), a programme for student summer employment has grown to around 5 000 participants annually by 2018 (Table 2.1). This programme subsidises work experience during the summer holidays for students in secondary education (aged 15-20). Municipal and other public institutions account for a large share of the employers. For a comparable programme in the United States, Davis and Heller (2017[7]) found that it prompted substantial behavioural changes but did not necessarily improve job prospects. Another programme introduced in 2014 under the Youth Guarantee subsidises the first employment of young persons for up to 12 months, paying the employer EUR 200 per months in the first and EUR 160 in the second half of the year (more in the case of persons with disabilities). While this programme has remained small, the high number of participants in student summer employment has increased total participation in employment incentives to 11 000 participants in 2018, or one-ninth of all participants in ALMP.

Rising participation in employment incentives was also driven by a programme promoting regional mobility within Latvia. It offers registered unemployed to reimburse up to EUR 100 per month of transport or housing costs they incur when attending a training course or taking up employment at a distance of least 15 kilometres from their residence, for the entire duration of the training or for the first four months of employment. As with subsidised employment, the part of this programme catering for young persons is provided under the Youth Guarantee. A first impact evaluation of this programme and its role in promoting regional mobility is undertaken in Chapter 4.

A small number of unemployed persons receive support for setting up a business or becoming self-employed (0.2% of all participants in ALMP in 2018). To be eligible, registered unemployed do not only need to express their intention to become an entrepreneur, but crucially need to demonstrate the necessary qualifications for the specific field in which they wish to establish themselves, as well as some knowledge in business administration. Participants are assisted with the development of a business plan and can receive up to EUR 3 000 as a start-up grant and, for the first 6 months, a monthly allowance at the level of the legal minimum wage. Chapter 4 offers an assessment of support for entrepreneurship or self-employment.

Until 2016, all ALMP programmes in Latvia catered for persons who are currently not employed. In January 2017, a programme was introduced that seeks to prevent that older employees lose their jobs. It promotes active ageing strategies to firms and offers career counselling, basic competency measures, workplace adjustment and measures for occupational health to employees aged 50 and above who are at risk of unemployment. This is deemed to be the case if they work part-time or at low wages, encounter health issues that reduce their work capacity, possess at most a secondary level of education, or are constrained by care obligations in the family. The programme is intended to involve 3 000 participants by 2023. For a similar programme in Germany, Dauth and Toomet (2016[8]) identify a small positive effect on the probability to remain employed.

Participation in ALMP is agreed in Individual Job Search Plans

When a newly unemployed person comes to register with the State Employment Agency, Latvia’s public employment service, the caseworker draws up an Individual Job Search Plan (IJSP). This plan details the rights and obligations of the unemployed person. Based on the result of a profiling tool, the stated interests of the unemployed person and the assessment of the caseworker, particular ALMP measures are identified as suitable and are included in the IJSP. The IJSP is reviewed in every following meeting with the caseworker and can be amended according to how the job search and participation in ALMP have proceeded thus far. Such meetings are mandatory and should take place at least once in two months. In addition, a newly unemployed person is expected to participate in an initial information session that presents rights and obligations, job search methods and ALMP programmes.

Eglīte, Krūze and Osis (2013[9]) assessed the entire registration process at the SEA for unemployed persons. They found that the first interview typically lasts for about 15 minutes only (which has since been extended to about 45 minutes), that a majority of unemployed persons consider the IAP helpful and that four-fifths learn about the various services available at the SEA during the interview. However, after the interview, Russian-speaking persons appeared significantly less informed than others about start-up incentives, and persons aged 15-24 appeared significantly better informed about employment opportunities abroad. Overall, only 6% did not know which steps they should take next.

The profiling tool could be used more effectively in practice

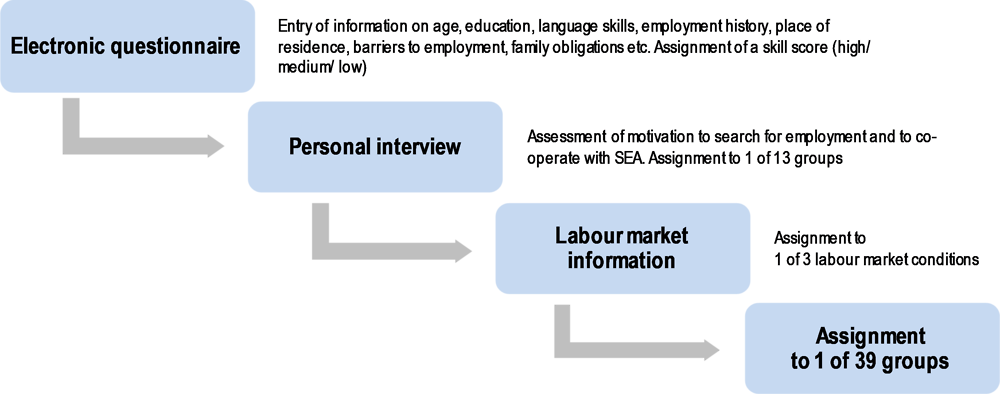

The State Employment Agency, Latvia’s public employment service, operates a profiling tool that is applied to all registered unemployed. It was gradually introduced in 2013 and rolled out by November 2013. It is typically used to identify early on those unemployed persons who are at risk of becoming long-term unemployed, and to select ALMP measures that are appropriate in their individual situation (OECD, 2015[10]). One of the reasons for the introduction of the tool was the need to ensure same services provided to persons with similar needs (detachment from the labour market) across the different local offices and caseworkers. The model uses both an econometric model and a counsellor’s assessment of clients’ motivation. It classifies clients in 39 groups depending on the probability they have to resume employment, combined with the results of self-assessed skills and motivation. Then, the system suggests a set of services and frequency of future visits to the different groups.

Figure 2.5 depicts the main steps of the profiling tool used in Latvia. A person who registers as unemployed initially fills out a questionnaire, typically online. The information gathered includes characteristics such as age and education as well as aspects of the individual situation such as employment history and family obligations. All answers exclusively reflect the self-assessment of the unemployed person. Some of the answers then translate into a skill score defined on a three-point scale. The econometric analysis predicts the client’s likelihood of finding a job by using information from the information system about the average length of unemployment for the groups of clients with the same demographic profile as him/her. The data used reflect the situation in the last 27 months and are updated every time a new client is registered and the profile is constructed for him/her.

A personal motivational interview with a SEA counsellor constitutes the second step. The counsellor uses a set of 12 pre-defined questions to assess the client’s motivation to cooperate with the SEA and motivation to search for a job and the client’s self-assessment of their skills and fills in the respective form in the profiling system. Here, a two-point scale is used (high vs. medium or low), so that the two motivation scores combine to four possible outcomes, for each of the three levels of the skill score. This leads to 12 groups; to highlight a group with particular risk, however, those with a low skill score and two low motivation score are separated out as an additional group. Finally, a three-point scale for current labour market conditions is used (i.e. without taking differences by region, education or occupation into account). The unemployed person is thus ultimately classified in one of 39 groups. Usually after 6 months, the motivation of the client and willingness to cooperate with the SEA are re-assessed, but this can happen earlier if there are substantial changes in the situation of the unemployed person.

Feedback from the local SEA branch shows mixed views about the use of the profiling tool. On the one hand, it helps counsellors to detect problems and propose appropriate measures for the different clients, but at the same time, it requires a longer time spent with the client. Branch workers also report the unwillingness of some clients to respond to the profiling questions. The profiling tool suggests a set of methods, ALMPs and priority order of receiving services. However, these suggestions constitute only one input into the counsellor’s effort to tailor his/her work with the client and develop the individual action plan (IAP), leaving some degree of discretion to the counsellor.

While the outcome of the profiling informs the IAP for the unemployed person and therefore also which ALMP measures are to be taken, it is not possible in practice to use a significantly different approach to each of the 39 groups. Profiling tools in other OECD countries including Australia, Austria and Germany seem to distinguish fewer groups (OECD, 2015[10]). Profiling tools also differ in the mix of information that is used as input, ranging from self-assessment of jobseekers to the caseworker’s assessment and to statistical results (Konle-Seidl, 2011[11]). In the case of Latvia’s profiling tool, the role of the jobseeker’s self-assessment has a bigger role to play relative to that of statistical information. The role of statistical results could be strengthened by accounting for the large regional differences in labour market conditions.

A number of evaluations of the profiling tool and its use have been conducted so far with the aim to strengthen its use and improve the labour market outcomes of the registered unemployed. In 2016, the SEA commissioned a first evaluation of the profiling tool to SIA Ernst & Young Baltic, with a focus on how well the ALMP measures selected after profiling correspond to the individual situation of the unemployed person. The evaluation concerns persons observed in 2015 and 2016 (two full years of observations) and the outcomes examined are those observed 6 months after profiling was conducted. The study evaluates the impact of the profiling method on the placement of the unemployed and assesses the effectiveness of the support measures proposed to the unemployed. It compares the outcomes of profiled and non-profiled clients. On average, non-profiled unemployed are more likely to find employment 6 months after registration, but differences between the two groups are not statistically significant. The authors of the evaluation suggest that these differences may be driven by differences in unobserved characteristics, including differences in motivation between the two groups, which is not measured for the group of the unemployed who have not been profiled.

The study recommended changes to the profiling matrix and greater efforts by caseworkers to encourage participation in the most appropriate ALMP measures based on the profiling outcome, while discouraging participation in other measures (SEA - Nodarbinātības valsts aģentūra, 2017[3]). With regards to the use of data in the SEA’s operations more generally, Box 2.2 outlines potential data-driven services that could help address some of the challenges encountered by the SEA. A number of these services have been implemented in other OECD countries.

Like other public employment services, Latvia’s State Employment Agency (SEA) collects a large amount of data through its interaction with jobseekers as well as employers and by monitoring ALMP measures. These data can substantially support the SEA’s work in several ways – through better targeting of ALMP measures to certain jobseekers, by raising the quality of services delivered, and by guiding internal performance management.

Statistical profiling of jobseekers draws on both the characteristics of the jobseeker to be profiled and on observations of previous jobseekers with similar characteristics. In Latvia as in several other OECD countries, statistical profiling is used to identify early on those jobseekers who have a high risk of becoming long-term unemployed (see Desiere, Langenbucher and Struyven (2019[12]) for an overview of current practice in OECD countries). This does not only allow concentrating the efforts of the public employment service on high-risk jobseekers, but also providing leaner services to jobseekers who do not need help with finding employment.

As a result of profiling, the interaction with jobseekers can therefore vary strongly. In the Netherlands, for example, initially only high-risk jobseekers are invited for an interview with a caseworker, while the interaction with low-risk jobseekers is typically limited to online services unless their unemployment duration approaches 6 months (Desiere et al. (2019[12])). Similarly, an IAP is concluded early on for high-risk jobseekers in Ireland, but only after 6 months for low-risk jobseekers. Along these lines, the interaction with jobseekers in Latvia could be targeted more strongly on those who have been profiled as having a high-risk of long-term unemployment. Greater reliance on online services in the interaction with low-risk jobseekers could be inscribed in Latvia’s Digital Agenda and e-Government Strategy, which aims at providing more and more public services online.

The SEA has also used profiling outcomes to identify suitable ALMP measures: a set of recommended measures is associated with each profiling group, and measures are ordered by priority. Using the available data, this approach could be broadened and refined at the same time: based on the experience with similar previous jobseekers, a statistical indicator for the expected time until employment is found could be calculated for each available ALMP measure but tailored to key characteristics of the jobseeker. For each jobseeker, the caseworker could then identify the ALMP measures that appear most promising in a statistical sense. The indicators would ideally update automatically as more data is collected over time.

A problem highlighted in this chapter – that many vacancies and many jobseekers are not registered with the SEA – might have data-driven solutions. Through web scraping methods, it may be possible to identify unregistered vacancies advertised elsewhere. By engaging with an external service provider, the Dutch public employment service obtains roughly one-third of the vacancies on its website from web scraping. Tailored lists of suitable vacancies from various sources could be sent to jobseekers on a regular basis, complementing their job search efforts. These lists could be further adapted to reflect the kind of vacancies that the individual jobseeker is interested in, by using data on the jobseekers’ clicks on vacancies in the lists or in the SEA’s vacancy database. For example, the Flemish public employment service in Belgium has begun analysing such click data from their vacancy database (Desiere et al. (2019[12])).

It may also be possible to identify unregistered jobseekers, for example discouraged workers or some recipients of disability pensions. To this end, data sources such as the Latvian Labour Force Survey may be used to identify combinations of characteristics that are often exhibited by persons who are not registered with the SEA but who wish to find employment. These insights can be used to target outreach efforts to unregistered jobseekers such that the contacted individuals have a high probability of being an unregistered jobseeker. High labour demand in Latvia currently offers a favourable context for efforts of this kind.

Finally, data could provide useful inputs to SEA’s performance management system. In order to account for regional labour market differences, SEA branches could be profiled based on regional indicators for labour demand and the characteristics of unemployed persons served by the branch. Performance benchmarks could then be defined for groups of SEA branches with similar profiles. This approach is taken in Germany (Blien, Hirschenauer and Thi Hong Van, 2010[13]). The performance evaluation of caseworkers could distinguish between jobseekers profiled as low-risk and those profiled as high-risk, as the latter may be substantially harder to place with an employer. This could help maintain incentives for caseworkers to give high-risk jobseekers the necessary attention.

Unemployment insurance and social benefits

This section briefly discusses the design of unemployment insurance and related working-age social benefits in Latvia. Unemployment insurance is publicly provided in Latvia as part of compulsory social security. Eligibility is determined as a function of paid contributions (through formal employment or self-employment) for at least 12 of the preceding 16 months. Registration with the SEA is a formal prerequisite. The level of the benefit depends on recipients’ social security contributions. Those who have adhered to the system for 30 years or more receive up to 65% of the average wage on which contributions were based. This proportion falls to 60% for 20-29 years, 55% for 10-19 years, and 50% for nine years or less. The unemployment benefit is paid for up to nine months but declines over time: the full benefit is paid for the first three months, three-quarters are paid for the next three months, and half is paid for the last three months. The quickly declining level of Latvia’s unemployment benefit gives recipients a strong incentive to find employment relatively soon. It thereby contributes to preventing long-term unemployment and also puts pressure on reservation wages. At the same time, this increases incentives to participate in ALMP measures only to receive a stipend (e.g. in training measures) that offsets some of the decline in the unemployment benefit.

Unemployment benefits may be too high for some and too low for others

The amounts paid as unemployment benefit can vary extremely widely in Latvia. According to OECD (2018[14]), the amounts of the Latvian unemployment benefit can range from 9% to 269% of the average wage in 2016. As a share of the national minimum wage, it can range from 25% to 767%. These ranges were the largest among all OECD countries for which data were available (except possibly for Finland, where no upper limit existed). In addition, the lower end of the ranges in Latvia were among the lowest, when compared with the ranges in other OECD countries. These findings suggest that some amounts may be too low to provide effective insurance against unemployment, while others may be too high to maintain incentives for job search.

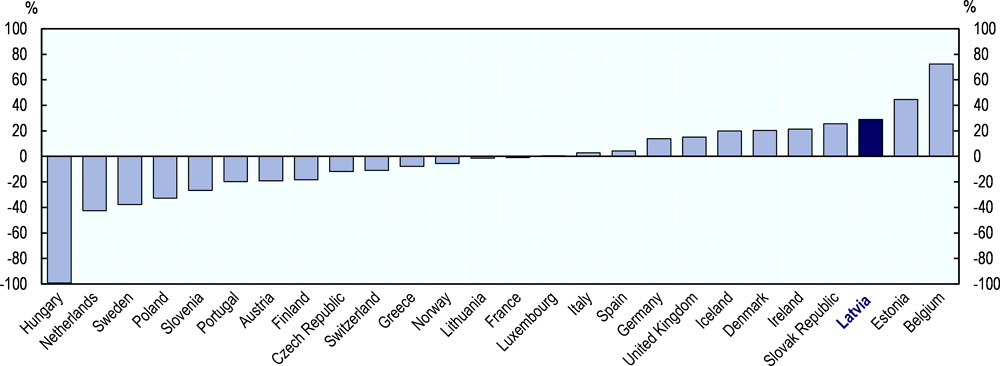

Figure 2.6 shows expenditures of OECD countries on unemployment benefits, as a share of GDP. This measure avoids problems of incomparability that might arise from the (often non-linear) dependence of benefits on prior wages and from benefits’ varying maximum duration. In 2016, Latvia spent less than 0.5% of its GDP on unemployment benefits. This level was low in comparison to many other OECD countries and also significantly below the OECD average (0.7% of GDP), but still somewhat higher than in Lithuania and Poland (around 0.2%). Although the design of Latvia’s unemployment benefit was changed in January 2012, expenditures in 2016 were close to the level in 2011. The permanently low spending on unemployment benefits in Latvia contrasts with the situation in other OECD countries that were severely affected by the economic crisis. Ireland, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain spent considerably more on unemployment benefits in 2011, but their expenditures have since declined strongly.

Several conditions for unemployment benefit receipt in Latvia have become stricter in recent years (Langenbucher, 2015[15]). For example, after three months of registered unemployment, job offers have to be accepted also when they are unrelated to the occupation of the unemployed person. Also the requirements for geographical mobility have increased (see Chapter 4 for details). Nevertheless, a score based on such requirements of occupational and geographical mobility, as well as on the required availability during participation in ALMP, still places Latvia in the most permissive quarter of OECD countries (Immervoll and Knotz, 2018[16]).

A sickness benefit is available for persons temporarily unable to continue working because of an accident or disease. Eligibility needs to be established through medial certificates. The (taxable) sickness benefit pays 80% of the previous wage for up to 26 weeks. The benefit can be extended subject to the approval by a medical commission. If the health condition meets the relevant criteria, the medical commission can also award a disability benefit.

The level of social assistance is comparatively low

As Latvia’s social security system does not offer unemployment assistance beyond the unemployment benefit, unemployed persons rely on social assistance whenever they are not eligible for the unemployment benefit or when it has expired. Access to the Guaranteed Minimum Income (GMI) is means-tested. A household qualifies if it is classified as needy with a monthly income below EUR 128 per person and lack of savings, and secondly, the net income per person in the household has been below the level of the GMI for the last three months. In this context, social benefits from municipalities and child allowances are not considered income.

For 2018, the national level of the GMI was set to EUR 53 per month per person. The level is based on an agreement between municipalities and the Ministry of Welfare, but does not follow from any particular methodology related to incomes or costs of living (Frazer and Marlier, 2016[17]). Municipalities, which are in charge of paying social assistance benefits, have the possibility to set a higher GMI level for their residents and for particular groups, such as persons with disabilities, retirees, and families with children.

Benefit payments are calculated as the difference between the existing household income and the guaranteed level of household income, i.e. the individual level of GMI times the number of persons in the household (Republic of Latvia, 2009[18]). In 2012, 95 000 persons (4.6% of the Latvian population) received on average EUR 35 per month, and about 90% of them were not in employment (Cālīte, Balga and Ālere-Fogele, 2014[19]). The GMI is typically combined with a housing benefit that is also available to households classified as needy. It is likewise paid by municipalities and its level varies, not least due to wide differences in housing costs.

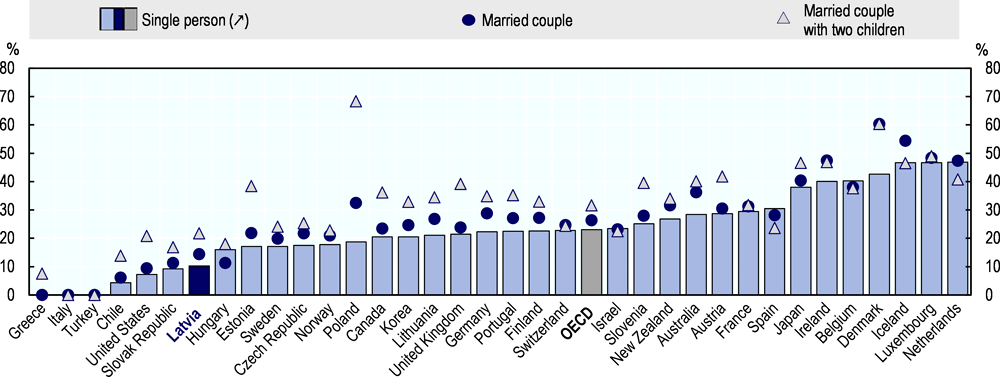

In comparison to other OECD countries, the targeted households remain relatively poor in Latvia despite social assistance: except for households with children, relative incomes of households who receive minimum income benefits are higher in the vast majority of OECD countries (Figure 2.7). In Latvia, the income of a single person receiving GMI benefits amounted to only 10% of the median income in 2016, while the income of a married couple receiving benefits reached 14%. Figures were lower in Chile, the United States and the Slovak Republic. Married couples with children were in a somewhat more favourable situation in Latvia: at 22% of the median income, their relative income with benefits approached the corresponding levels in Norway and Israel.

According to data from the Latvian Labour Force Survey for 2012-2016, close to half of all GMI benefit recipients have low levels of educational attainment, while those with a tertiary level of education represent less than 1% of recipients. Young persons are relatively rare among the recipients, whereas the age groups 35-44, 45-54 and 55-64 each account for roughly one quarter of recipients.

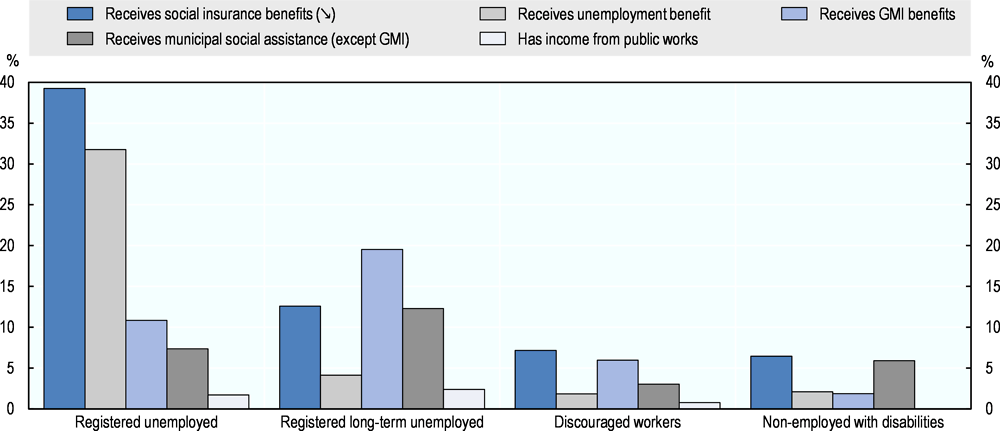

About one in five long-term unemployed persons receive GMI benefits, whereas this share is about half as high for all registered unemployed persons (Figure 2.8). Among discouraged workers, only 6% receive GMI benefits. Using data for 2010, Gotcheva and Sinnott (2013[20]) found that overall 3% of Latvia’s population received GMI benefits, and 14% of those in the lowest quintile of the income distribution. They conclude that the strong targeting at the lowest quintile, in which 90% of GMI benefits were granted, is associated with low coverage, so that many households classified as needy do not receive these benefits.

The number of disability benefit recipients is growing quickly

Support for persons of working age with disabilities is provided in Latvia through three mutually exclusive benefits, depending on the insurance coverage. Firstly, a disability pension is available for those who have been in the social security system for at least three years and have been assessed by a state medical commission after referral by a general practitioner. The medical procedure distinguishes three degrees of disability: very severe (classified in group I), severe (group II) and moderate (group III). The level of the disability pension is determined individually, based on the degree of disability, whether or not the disability developed early in life, the prior average wage, and the number of years in the social security system. Whenever a person has adhered to the social security system for less than three years, the minimum amount of the disability pension applies. The disability pension is not means-tested but subject to income tax.

Secondly, a person who is covered by social security and whose disability is the consequence of an accident at work or an occupational disease is eligible for the so-called compensation for the loss of work capacity, instead of the disability pension. The degree of disability is assessed by the same state medical commission. The percentage of the prior average wage that is paid as benefit depends on the loss of work capacity, from 35% in the case of a 25% loss of work capacity up to 80% in case of a total loss of work capacity. This benefit is likewise not means-tested but subject to income tax (except under the tax regime for micro-entrepreneurs).

Thirdly, the state social security benefit covers cases which are not covered by the disability pension nor the compensation for the loss of work capacity, notably because a minimum insurance duration is not met. A precondition for this benefit is at least five years of residence in Latvia. The monthly level of the benefit is fixed for each degree of disability: EUR 102 in group I (EUR 171 in case of disabilities since childhood), EUR 90 in group II (EUR 149) and EUR 64 in group III (EUR 107). This benefit is not taxable.

In 2015, the number of recipients of disability benefits exceeded 96 000 and approached 99 000 in 2016, according to the Eurostat Social Protection Database. In 2007, this number was still below 75 000. Figure 2.9 shows that the number of recipients of disability benefits has grown especially fast in Latvia between 2007 and 2015 (+29%), compared to other European OECD countries. While men represented the majority of recipients in Latvia in 2015 (50 000), growth over the period 2007-2015 was substantially stronger for women (+35%) than for men (+24%). Similarly, figures from the OECD Social Expenditure Database indicate that the number of state social security benefits has grown relatively quickly between 2007 and 2014. In 2007, these benefits made up 22% of all disability benefits, rising to 25% in 2011 and 27% in 2014. According to Latvia’s Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, a growing number of disability benefits are granted due to tumours and circulatory system diseases. Benefits for persons with disabilities have also been extended – in particular, allowances for special care needs were introduced in 2007 and are mostly received by women.

A high tax wedge limits labour supply incentives

The social benefits available to working-age persons may in some cases have implications for the willingness to work: benefit receipt can seem preferable to employment, notably when there may be opportunities for informal work at the same time. In Latvia, the disability benefits are the most attractive benefits because they are potentially unlimited and provide a significantly higher income than the GMI. It is therefore very important to ensure that the medical assessment procedure remains sound and accurate. A key determinant for labour supply incentives are the financial gains from taking up work rather than receiving benefits (Fernandez et al., 2016[21]).

In comparison to other OECD countries, the tax wedge in Latvia appears high for low incomes (the tax wedge is defined as the sum of income tax and social security contributions net of benefits, divided by total labour costs). For example, the tax wedge reaches 40% of labour costs for someone working at the minimum wage, a higher level than in almost all other OECD countries (OECD, 2016[22]). According to the European Commission (2017[23]), changes to tax legislation implemented in recent years have hardly reduced the tax wage for low incomes. However, a tax reform implemented in January 2018 will reduce the tax wedge for low-income earners and families with children over the coming years.

Maintaining labour supply incentives is especially important for disadvantaged groups in the labour market: taking up some (even marginal) employment makes it significantly more likely that a person is employed in the long run, rather than unemployed (Caliendo, Künn and Uhlendorff, 2016[24]). Simulating the situation in Estonia, Brixiova and Égert (2012[25]) found that reducing the tax wedge especially for low-wage workers would lead to a decrease in the rate of long-term unemployment.

Sanctions are strict but cannot be applied gradually

In Latvia, recipients of the unemployment benefit face a number of conditions and obligations (Langenbucher, 2015[15]). A person who becomes unemployed by resigning from a job can receive the unemployment benefit only after a waiting period of two months, and there is no justification for a resignation that would lead to an exception from the waiting period. A registered unemployed person must not miss scheduled meetings without a good reason, is obliged to participate in the ALMP measures specified in the IAP, must not refuse suitable job offers more than once, and should document at least three job applications in a two-month period (at least one job application in regions with high unemployment). Persons who fail to comply with these rules typically lose the status of registered unemployed, so that unemployment benefit payments are terminated and the remaining entitlement is lost.

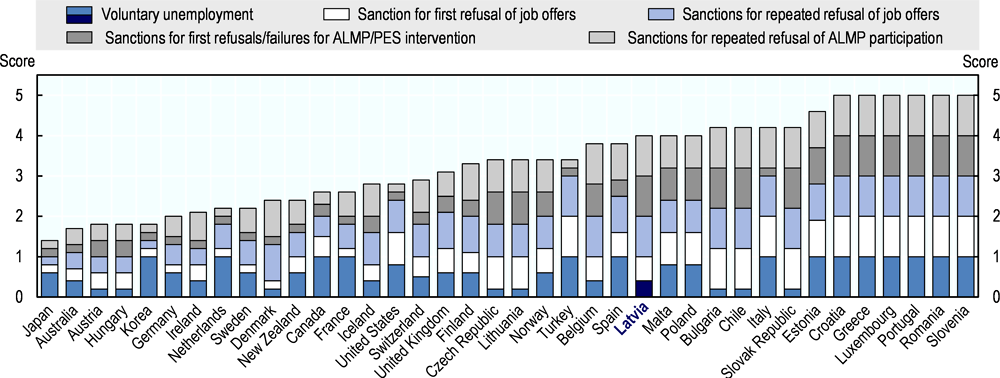

Sanctions in Latvia are strict in comparison to other OECD countries, yet not as strict as those in some OECD countries that were also severely affected by the economic crisis, such as Greece, Italy, Portugal and Slovenia (Figure 2.10). In only two respects, sanctions are not as strict in Latvia as in some other OECD countries: the first job offer may be rejected without consequences, and other countries impose longer waiting times for persons who resigned from their job.

Recipients of GMI benefits who are of working age have to register with the SEA, within one month of filing for benefits and have to sign an IAP, similarly to recipients of unemployment benefits. Depending on the IAP, they may therefore face the same requirements as recipients of the unemployment benefit. The typical sanction in their case is also losing the status of registered unemployed, leading to the suspension of their benefits. Other reasons for suspending benefit payments include providing incomplete or false information, refusing medical examination or treatment, failing to collect benefits awarded by the state social security system and missing scheduled appointments with the municipal social service (Republic of Latvia, 2009[18]). In general, municipal social services and benefit recipients also agree on an IAP, and benefit payments may be suspended if it is violated in bad faith. However, given the role of the GMI for basic income maintenance, benefits are not normally suspended for more than three months. Recipients of disability benefits are expected to work within their capacity, as determined by the degree of their disability. While disability benefits are not suspended in order to sanction behaviour, renewed medical examinations may change the assessed degree of the disability.

The existing sanctions applied in Latvia therefore appear limited to suspending the entire benefit, at least temporarily. Reductions in the level of the benefit are notably absent, as are other less severe sanctions such as additional obligations in terms of appointments or documentation. However, using less severe sanctions may have by and large the same effects on compliance, while avoiding the harshness of benefit suspension especially for those who have no other source of significant income. In addition, less severe sanctions could be used as a motivation in circumstances where benefit suspension is either not justified or would do more harm than good.

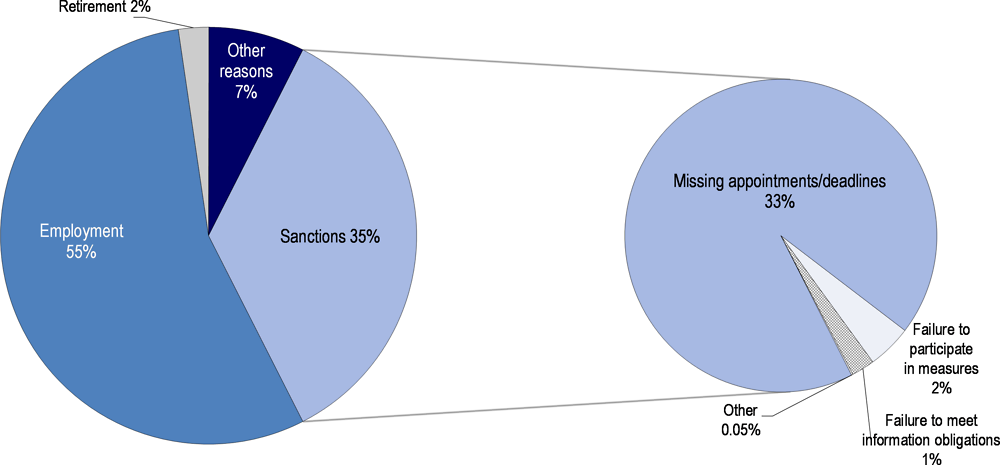

Figures from the SEA on the use of sanctions in 2016 offer some hints that less severe sanctions would have a role to play. While sanctions terminated the status of registered unemployed in 37 000 cases, almost all (93%) were due to missing a scheduled appointment or a deadline (Figure 2.11). Failure to participate in an ALMP measure accounted for and failure to meet information obligation (including giving false information) accounted for 5% and 1% of all sanctions, respectively. By contrast, refusing more than one job offer and failure to search for work only accounted for about 0.1% of sanctions in 2016. It thus appears that sanctions are hardly used whenever they do not have to be used or when they might be applied mistakenly, based on limited information. In these situations, less severe sanctions might still be used, with positive effects on compliance. Over the last few years, the share of sanctions among outflows from the status of registered unemployed steadily declined, from 46% in 2012 to 35% in 2016.

Table 2.2 shows which characteristics among registered unemployed persons were linked with sanctions in 2016/2017. They are relatively unlikely to be sanctioned while they still receive unemployment benefits: the risk is below 40% of that found for non-recipients. In terms of unemployment duration, the risk of sanctions is highest between seven and 12 months of unemployment, around the time when unemployment benefits cease. Sanctions are therefore much more likely to occur when unemployed persons have little to lose. Unemployed persons aged 15-24 exhibit a similarly low risk of being sanctioned, compared to the age group 35-44. Women are substantially less likely to be sanctioned than men, and persons who participated in public works exhibit more than twice the probability of being sanctioned of non-participants.

Sanctions ideally raise transitions to employment, but they can also raise transitions out of the labour force and might put pressure on reservation wages. Analysing a reform in the United Kingdom in 1996 that significantly increased job search requirements for recipients of unemployment benefits, Petrongolo (2009[26]) found that those subject to the new requirements were more likely to move to disability benefits and tended to have lower salaries in the following years. Van den Berg, Uhlendorff and Wolff (2017[27]) consider unemployed men younger than 25 in Germany who face similarly strict sanctions as unemployed persons in Latvia – their benefits are routinely suspended for three months. The study finds that sanctions raised transitions to employment but at lower wages, and also raised transitions out of the labour force. Busk (2016[28]) reports results from Finland that highlight the design of the unemployment benefit: recipients of flat-rate benefits reacted to sanctions by moving to employment, while recipients of benefits based on prior wages rather moved out of the labour force.

The role of the State Employment Agency in ALMP

This section focuses on the delivery of Latvia’s labour market policy by various institutional actors. It discusses the role of each institution, their activities in practice and some of the challenges they face. Most attention is given to the State Employment Agency (SEA), Latvia’s public employment service that is responsible for the design and delivery of all ALMP, provides services to employers and pays unemployment benefits. A second focus is placed on municipalities, which are in charge of social assistance and co-operate with the SEA on ALMP for recipients of social assistance.

Almost all SEA staff possess a tertiary education

The total number of SEA staff was 840 in 2017, after 862 in 2016. Three-quarters of them (625 staff) belong to one of 28 local offices, while the remaining quarter (215 staff) belong to the SEA’s central office and work in management, oversight of ALMP, accounting and finance, human resources and IT as well as statistics and legal issues. Job profiles are divided mainly into caseworkers (22% of all staff), staff working with employers (11%), as well as career counsellors and staff who implement specific projects funded by the European Social Fund (ESF). The latter notably includes measures provided under the Youth Guarantee.

The vast majority of SEA staff is made up by women – in 2016, men only represented 7%, (SEA - Nodarbinātības valsts aģentūra, 2017[3]). Half of them were between 40 and 59 years old, while 40% were aged between 20 and 39. Almost all (98%) possessed a tertiary level of education, and this level is also expected of all new recruits. About 45% of staff had the status of civil servant. The turnover rate stood at 11% in 2016 but was significantly higher in Riga than in rural areas, likely because SEA wages are less competitive in Riga’s high-wage environment.

A large part of the financial resources available to the SEA are provided by the European Union. In 2016, grants notably from the ESF and co-financing from Latvia’s national budget together accounted for 83% of the SEA’s budget (SEA - Nodarbinātības valsts aģentūra, 2017[3]). The remainder derived from social security contributions – up to 10% of annual expenditures from social security contributions may be allocated to ALMP. A proposal for the SEA’s annual budget is drawn up by the Ministry of Welfare and requires approval by parliament. In addition to changes due to staff turnover, the strong dependence on ESF funding induces some volatility in the budget as specific projects begin or expire, which also explains the slightly lower level of staff in 2017 compared with 2016. ESF funding of ALMP under the Youth Guarantee expired in 2018.

Low registration of jobseekers and vacancies limits the SEA’s role in matching

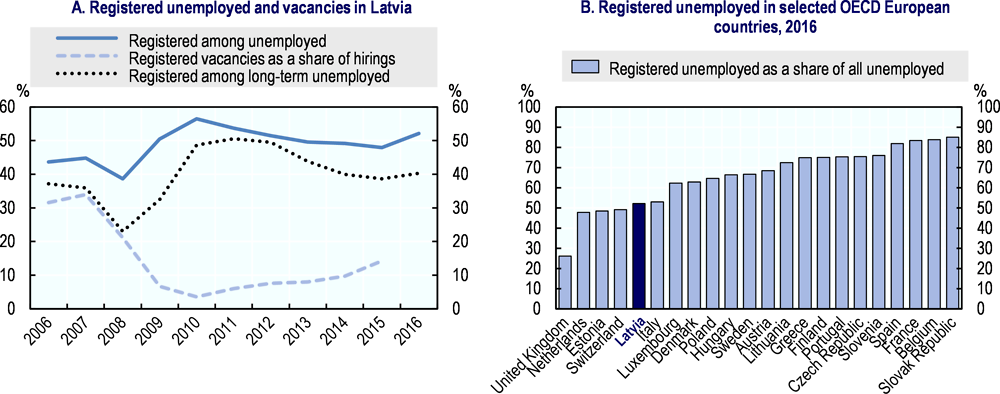

A public employment service (PES) such as the SEA can play a key role for matching on the labour market. As precondition for effective intermediation in matching, the PES has to be aware of jobseekers and vacancies in the first place, and is ideally in direct contact with both sides. In practice, however, the reach of the PES is often limited to a fraction of jobseekers and vacancies, and Latvia’s SEA is not an exception: registered unemployed persons accounted for about half of all unemployed persons in the last few years, and the number of registered vacancies may have been below 20% of all hirings until at least 2015 (Figure 2.12, Panel A). The first measure is based on data from the European LFS and is thus comparable across European OECD countries. It indicates that comparatively few unemployed in Latvia are registered with the PES (Figure 2.12, Panel B). The second measure comes with caveats. Especially when unemployment is high, many vacancies are filled quickly and do not enter a count at a particular point in time (e.g. at the end of the month). By contrast, hirings are all observed unless employment ended very soon again. This factor biases the estimated share of registered vacancies downwards and helps explain the extremely low values in 2009-2013. A factor that partially offsets this bias is the retraction of unfilled vacancies.

The changes over time in Figure 2.12, Panel A plausibly suggest that the share of registered unemployed was comparatively high in 2010/2011. In these years, many unemployed had lost their jobs only recently and could obtain unemployment benefits, provided they registered. At roughly the same time, registered vacancies were especially low compared with all hirings, likely because vacancies could easily be filled without involving the SEA, given a large pool of unemployed persons. Similarly, the strong rise of registered vacancies relative to all hirings in 2015/2016 might reflect employers’ rapidly increasing difficulties to find suitable candidates without recurrence to the SEA (see Chapter 1). In addition, a requirement has been introduced for public sector employers to register their vacancies.

Recent amendments (applied since January 2019) to Latvia’s labour code would require all employers who register their vacancies to also indicate a wage range. While this information is useful for jobseekers, might contribute to their protection and might help prevent informal payments, wage information can be sensitive information for employers, often disclosed only at later stages in the recruitment process. In particular, employers might not want to share this information with other employers who compete with them for the same jobseekers. If required to publicly disclose a wage range, some employers might therefore not register vacancies that they would otherwise register with the SEA. However, sufficiently broadly defined wage brackets could still be acceptable to them. More generally, in order to encourage registration of vacancies as much as possible, registration should be as easy as possible.

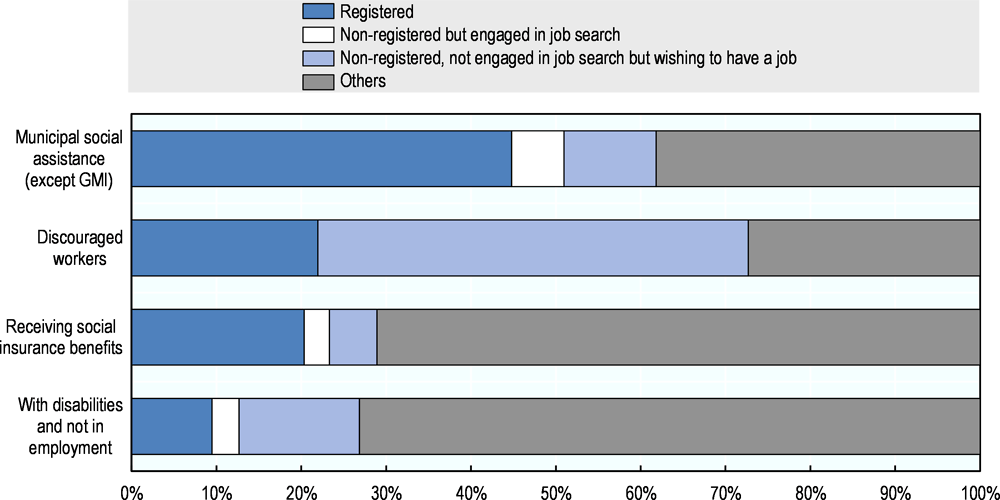

While persons who received unemployment benefits or GMI benefits have to register with the SEA, Figure 2.13 indicates the extent of registration in some other groups of jobseekers. In 2012-2016, registered persons accounted for less than one-quarter of discouraged workers, persons receiving social insurance benefits and persons with disabilities who were not in employment. This share reached 45% among persons receiving municipal social assistance other than GMI benefits, such as housing benefits and reimbursements of medical expenses. Figure 2.13 further indicates a potential of jobseekers in these groups that were not registered with the SEA. Some of the non-registered persons were engaged in job search, and substantial shares in all groups wished having a job although they were neither registered nor engaged in job search: around 10% of persons receiving municipal social assistance, persons receiving social insurance benefits and persons with disabilities who were not in employment, and just over half of all discouraged workers.

On the other hand, not everyone who is registered with the SEA engages in job search. Based on the same data as in Figure 2.13, one-quarter of those registered with the SEA in 2012-2016 were not engaged in job search. However, most persons in this particular group (72%) nevertheless wished having a job. The proportions vary only little across age groups. The share of those not engaged in job search only stood out in the age group 55-64, where it approached one-third of those registered. Among those who do not engage in job search, the share who wish having a job was lowest in the age group 15-24 (65%). In addition to the challenge of reaching out to non-registered jobseekers, there is thus also some scope for activating more of the registered jobseekers.

Many long-term unemployed persons have little incentive to register

When the unemployment benefit has expired after nine months, or after 11 months in case of an initial waiting period, an unemployed person can receive benefit payments due to the GMI. Registration with the SEA is a precondition for these benefits. Because of the means test involved, however, many unemployed persons are not eligible for these benefits and consequently reluctant to stay registered with the SEA, especially if this requires them to attend unwanted meetings or ALMP measures. In practice, they simply miss one of the next scheduled appointments, which contributes to the very frequent terminations of the official unemployment status due to missed appointments, as mentioned above.

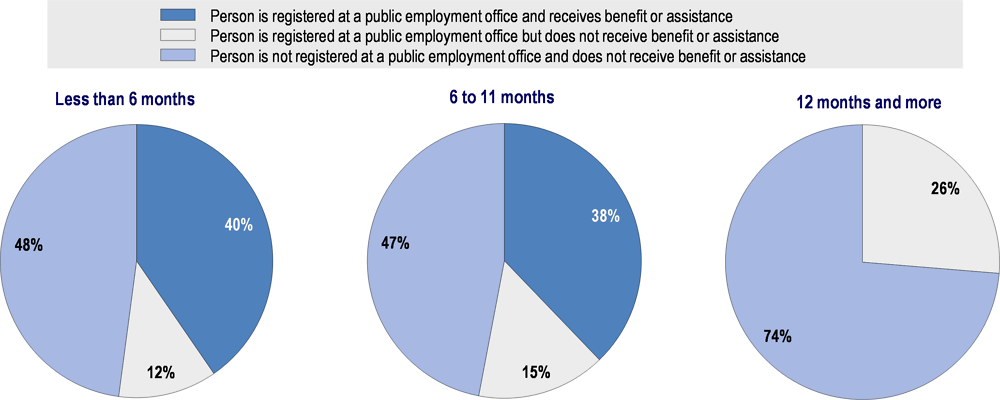

Figure 2.14 shows how receiving the unemployment benefit and registration with the SEA are linked to unemployment duration. Among those with unemployment duration below 6 months, 52% were registered with the SEA in 2017 and 40% received unemployment benefits. Almost the same share (53%) of those with durations from 6 to 11 months was registered. At unemployment durations of 12 months or more, however, three-quarters were not registered and no-one still received unemployment benefit. Because the share of non-registered persons is substantially larger among the long-term unemployed, focussing on registered unemployed persons especially neglects the long-term unemployed.

The results in Figure 2.14 further highlight that relatively few of the short-term unemployed receive unemployment benefits. Given that unemployed persons who are entitled to unemployment benefits can be expected to collect them (unless benefit amounts are very low), this indicates that many are either not eligible under the current rules or were eligible but lost their entitlement due to sanctions. A further reason may be that access to unemployment benefits has become more difficult for seasonal workers. Across all durations, only 24% of all unemployed in 2017 were registered with the SEA and received unemployment benefits, another 18% were registered but did not receive unemployment benefits, and 58% were neither registered nor receiving benefits.

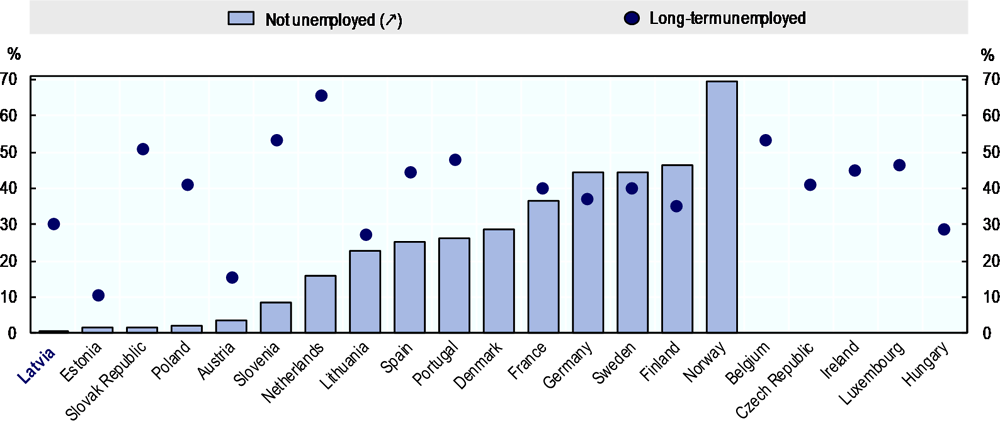

For European OECD countries, Figure 2.15 characterises those who were registered with the public employment service in 2016. Long-term unemployed accounted for 30% of those registered in Latvia. This share was rather low in comparison: while similar shares were also observed in Lithuania and Hungary, significantly lower shares were only observed in Austria and Estonia (16% and 10%, respectively). Latvia stood out, however, by registering hardly any persons who were not classified as unemployed by the public employment service (0.26%), such as employed persons who look to change jobs, participate in career counselling or engage in training. To some extent, this reflects that programmes for life-long learning were shifted to the Ministry of Education and Science. By contrast, persons who are not unemployed represented almost 70% of those registered in Norway and more than 40% in Finland, Germany and Sweden. In most European OECD countries, a significant share of registered persons are not unemployed.

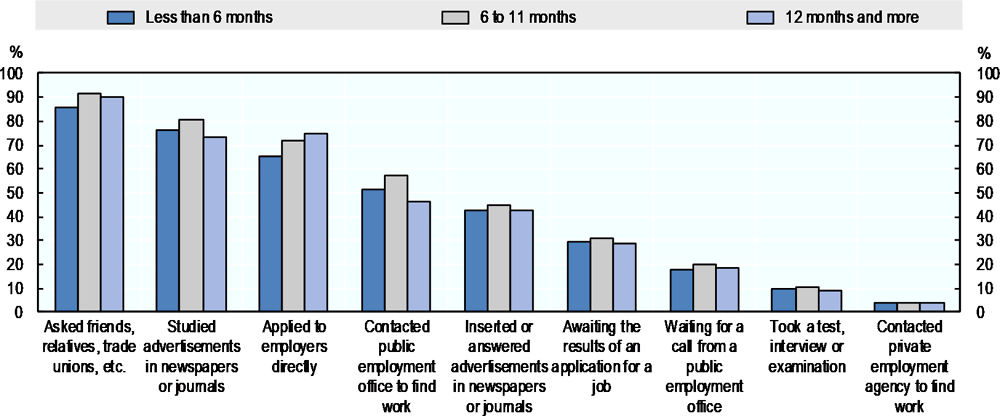

In line with the results in Figure 2.12, around half of the unemployed persons in Latvia made the SEA part of their job search in 2015 (Figure 2.16). The share was highest for those with unemployment durations from 6 to 11 months (57%) and lowest for the long-term unemployed (46%). Three job search methods were used substantially more often by all unemployed persons, irrespective of the duration of unemployment: asking friends and family about vacancies, studying published job advertisements, and direct applications to employers. The long-term unemployed relied comparatively strongly on direct applications. If the maximum search effort is defined as everyone using every available job search method, those with unemployed durations below 6 months and the long-term unemployed appear to exert similar job search efforts overall (reaching 42% and 43% of the maximum search effort, respectively). Those with durations from 6 to 11 months appear to be especially engaged in job search (reaching 46% of the maximum).

Engaging employers more in the work of the SEA requires trust

For employers, the incentive to engage with a PES is less clear than for unemployed persons who are entitled to unemployment benefits. It is therefore plausible that the share of registered vacancies is lower than the share of registered unemployed persons, as indicated by Figure 2.12. In principle, a PES can facilitate recruitment, especially when a number of positions need to be filled within a short time horizon. In practice, however, the added value of a PES for employers strongly depends on the services offered to them and on the available candidates. Evidence from the German vacancy survey suggests three main reasons why employers who are currently recruiting do not engage with the PES: they expect that the candidates available from the PES would not be suitable (Müller, Rebien and Stops, 2011[29]). Small enterprises also find it complicated to use the services offered by the PES or are not aware of them. Holzner and Watanabe (2016[30]) similarly argue that employers expect candidates from the PES to be less suitable on average than other candidates. However, they also point out that employers may want to engage with the PES because the probability to fill vacancies at relatively low wages could be higher in this context than in a more competitive environment. These findings align with circumstantial evidence – including from Latvia – that employers engage especially rarely with the PES when they seek to fill positions requiring high skills and offering high wages, likely because suitable candidates for such positions have a comparatively low risk of unemployment and are therefore difficult to find in the pool of candidates from the PES.

The services that the SEA offers to employers include publication of vacancies, access to a database of candidates, arranging interviews, accompanying candidates to job interviews, and organising job fairs. In 2012, the services for employers were evaluated in the context of the support through the ESF, using a random sample of 3 600 employers, of which 800 had used SEA services (Eglīte et al., 2012[31]). Based on interviews with executives at the surveyed employers, it emerged that employers primarily engaged with the SEA by publishing vacancies, using the database of candidates and participating in ALMP programmes that involve training at the employer. In addition, private job placement services turn to the SEA for advice on legal provisions and regulations. Overall, employers were rather satisfied with the services provided by the SEA, and more than one-quarter of those currently using some SEA service intended to also explore other SEA services. However, only one-fifth of surveyed executives who have used SEA services considered them a significant help in the selection of candidates.

In various contexts, the survey detected dissatisfaction with the administrative burden, notably requirements for documentation (Eglīte et al., 2012[31]). This was expressed by employers who participated in ALMP measures for training as well as by local government officials involved in running the temporary public works programme. While respondents appeared to understand the rationale for the required documentation, they believed that simplifications would be possible and that the benefit from SEA services might only justify taking on the administrative burden when several positions are to be filled simultaneously. Administrative requirements may have decreased in recent years, notably in the context of the SEA’s “Strategy for the co-operation with employers 2017-2019”. The website of the SEA, considered by respondents as a key source of information and gateway to services, has been restructured and made more user-friendly.

The survey further provided numerous hints that employers consider direct working relationships with SEA representatives very important for successful co-operation. For example, employers in rural areas were generally more satisfied with SEA services, not least due to more extensive personal contact. More direct contact and more individual co-operation were also among employers’ main suggestions for improvement. Employers also indicated that direct contacts allowed them to gather information about SEA services more easily. Their responses align with results from Switzerland on greater success with placements where PES staff have good working relations with employers (Frölich et al., 2007[32]).

In contrast to more anonymised contact, the trust in established working relations enables caseworkers to credibly recommend selected candidates as suitable for the particular employer. At the same time, caseworkers can learn about open positions that are not advertised publicly. While the available staff resources limit the possibilities for extensive direct contact with employers, exceptions can be made for employers who frequently use SEA services and hire from its pool of candidates: in 2018, the SEA began assigning individual consultants to especially large employers.

SEA caseworkers play a crucial role especially for the long-term unemployed

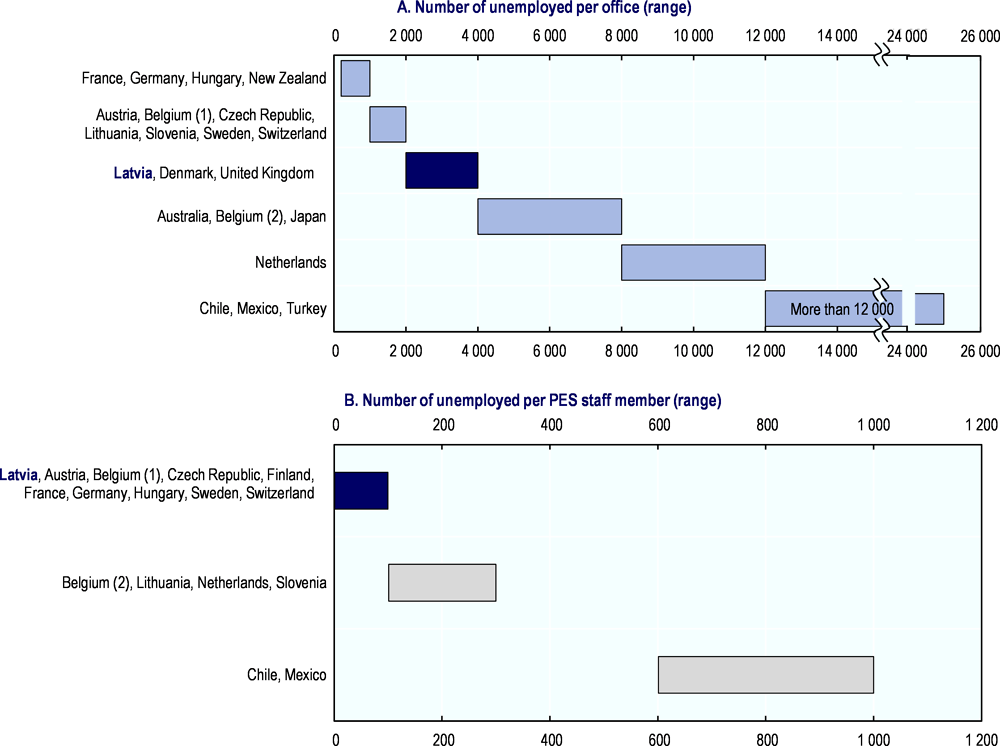

Figure 2.17 shows crude yet internationally comparable measures of caseloads: the number of registered unemployed persons per staff member of the PES and per office of the PES. The latter measure can also serve as an indication of accessibility of the PES in the sense that it is widely present through local offices. By one measure, Latvia falls into the same range as a number of other European OECD countries with up to 100 unemployed persons per member of staff, while substantially higher ratios (100-300) are observed in Belgium, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Slovenia (Figure 2.17, Panel B). Much higher ratios (600-1 000) occur in Chile and Mexico. By another measure – unemployed persons per PES office – Latvia ranges in the middle of the OECD for which data are available (Figure 2.17, Panel A). While the number of unemployed persons per office in Latvia is thus in the same range as in Denmark and the United Kingdom (4 000-6 000), substantially lower ratios are observed in France, Germany, Hungary and New Zealand.

Depending on how many staff of the PES are not caseworkers, however, the caseload per caseworker can be considerably higher than shown in Panel B of Figure 2.17. In Latvia, the monthly caseload per caseworkers was between 350 and 500 in 2017. The caseload also varied substantially across regions, being especially high in Riga and relatively manageable in many rural areas.

On this background, caseworkers who are under strong pressure even have an incentive to allocate less time and effort to complex cases than to other cases: given that they lack the time to treat complex cases with the necessary care, it could seem more promising to focus on those unemployed persons who can still be placed with little time invested. By consequence, unemployed persons who are initially disadvantaged would then face a higher probability of not being placed and thus becoming long-term unemployed, which would compound their disadvantages. Provided there is a reliable profiling tool, caseworkers could be incentivised by some kind of premium to also treat those cases that the profiling classified as complex. However, this premium must be independent of unemployment duration, as it might otherwise create a perverse incentive to produce long unemployment durations (OECD, 2015[10]).

The SEA currently approaches this challenge in several ways. While caseworkers do not specialise in more or less complex cases, rotation within local offices leads them to focus regularly on the complex cases for some time. Guidelines developed in 2016 recommend monthly meetings for rather complex cases and make monthly meetings compulsory after unemployment duration of three months, compared to bi-monthly meetings during the first three months (SEA - Nodarbinātības valsts aģentūra, 2017[3]). The use of e-services is extended in order to save time on less complex cases. Whenever the monthly caseload falls below 350, the local office has the choice between reducing the caseworker’s working hours and allowing the caseworker more time per case.

In recent years, several OECD countries have experimented with reducing caseloads at least temporarily. The observed results typically include a positive effect on transitions into employment. For example, an experiment in Germany allowed only a few local offices to reduce caseloads by hiring more caseworkers (Hainmueller et al., 2016[34]). This lead to intensified counselling, greater placement efforts, shorter unemployment durations and lower local unemployment rates. For the Netherlands, the fact that caseloads vary across local offices and over time was exploited to estimate the effect of lower caseloads, and a significant positive impact on exit from unemployment was found for short-term unemployed persons (Koning, 2009[35]). Both studies concluded that additional caseworker resources were cost-effective, leading to net savings. Numerous similar results were obtained for instances of more intensive counselling (Parent and Sautory, 2014[36]).

Internal training at the SEA aims at raising the capabilities of caseworkers and other staff. In 2016, a number of workshops were organised on specific topics of ESF projects, in addition to training on recurrent issues such as public procurement, customer service skills, IT skills, coaching methods and recent legal changes (SEA - Nodarbinātības valsts aģentūra, 2017[3]). In order to learn from the experience of other PES, SEA representatives participated in 50 events in 2016, including meetings in the framework of the Baltic Employment Services Co-operation Agreement.

While a large share of caseworkers is proficient in Russian, the Law on the State Language determines that only the Latvian language should be used, and this includes SEA offices in regions where a majority of the population speaks Russian in everyday life. It is not clear how many interactions between unemployed persons and caseworkers therefore suffer from communication problems. In addition, many unemployed persons might be bilingual, but especially some low-skilled unemployed persons might face a language barrier in SEA offices that undermines their chances to fully benefit from SEA services.

A number of studies suggest that there are gains from similarity between the caseworker and the unemployed person. For example, Behncke, Frölich and Lechner (2010[37]) report positive effects on transitions to employment for pairings of caseworkers and unemployed persons from the same social group, defined by age, gender, education and nationality. Further such results were found by Egger and Lenz (2006[38]) and Lagerström (2011[39]) for Switzerland and Sweden, respectively. The underlying reason for these findings could be caseworker’s attitude or effort: Granqvist, Hägglund and Jakobsson (2017[40]) found that caseworkers’ attitudes play a significant role for outcomes. The fact that nationality or origin appear to be one criterion of similarity suggests that a common native language may contribute to effective interactions between caseworkers and unemployed persons.

Performance in the SEA is managed through objectives at various levels