7. Merit

This chapter provides a commentary on the principle of a merit-based system contained within the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity. It describes how a merit-based and professional public sector dedicated to public service values contributes to public integrity. It focuses on setting predetermined, appropriate qualification and performance criteria for all positions, along with objective and transparent personnel management processes. Moreover, it demonstrates how open application processes that give equal access to all potentially qualified candidates, and oversight and recourse mechanisms that ensure consistent and fair application, contribute to the broader public integrity system. The chapter also addresses the four commonly faced challenges related to merit-based systems: timely decision making; recruiting new skills and competencies; ensuring representation and inclusiveness; and addressing the fragmentation of public employment.

A civil service selected and managed based on merit, as opposed to political patronage and nepotism, presents many benefits. Hiring people with the right skills for the job generally improves performance and productivity, which translates into better policies and better services which in turn make for happier, healthier and more prosperous societies (Cortázar, Fuenzalida and Lafuente, 2016[1]). Meritocracy has also been shown to reduce corruption (Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell, 2011[2]; Meyer-Sahling and Mikkelsen, 2016[3]). Having merit systems in place reduces opportunities for patronage and nepotism, and also provides the necessary foundations to develop a culture of integrity.

Indeed, clientelism, nepotism and patronage can be forms of corruption when they result in the use of public funds to enrich people based on their family ties, political affiliations or social status. In extreme cases, public positions can be created with the intent of providing a revenue stream to reward political allies without any real necessity for work. In other cases, positions in the public sector can be bought and sold “under the table”. Merit-based systems reduce these risks significantly by making positions transparent and requiring clear justification for their existence. First, they make it more difficult to create “ghost” positions (positions that are not needed, where people do not perform essential work) for the purposes of rewarding friends and allies. Second, objective and transparent decision-making processes make it more difficult to appoint people to positions when they do not qualify for them. People may still take steps to unfairly influence the system, but recourse mechanisms and oversight functions ensure that rules are enforced and there are consequences for those who try to cheat.

While such extreme cases of job-based corruption are rare in OECD countries, a more common version of nepotism may exist in some member countries when managers or politicians appoint people to positions based on their personal ties. While that kind of nepotism can appear less critical, it threatens the values and culture of public service that public sector institutions strive to nurture. This is because a merit-based civil service is an essential foundation upon which to develop a culture of integrity. Merit provides the right kinds of incentives and accountabilities that underpin professionalisation, the public service ethos and public values.

A merit-based civil service contributes to reducing overall corruption across all areas of the public sector. There are a number of reasons for this (Charron et al., 2017[4]), including:

Meritocratic systems bring in better-qualified professionals who may be less tempted by corruption.

Meritocracies create an esprit de corps that rewards hard work and skills. When people are appointed for reasons having nothing to do with merit, they may be less likely to see the position itself as legitimate but instead as a means to achieve more personal wealth through rent-seeking behaviour. There is also a motivational quality about merit systems that reinforces public service.

Another way that meritocracy has been shown to reduce the risk of corruption is by providing long-term employment. This tends to promote a longer-term perspective that reinforces the employee’s commitment to their job and makes it less tempting to engage in short-term opportunism presented by corruption. Conversely, if people know that their job will not last long, they may be more easily encouraged to use their position for personal gain during the short time they have.

The separation of careers between bureaucrats and politicians is also shown to provide incentives for each group to monitor the other and expose each other’s conflicts of interest and corruption risks. Conversely, when the bureaucracy is mostly made up of political appointments, loyalty to the ruling party may provide disincentives for the bureaucracy to blow the whistle on political corruption (and elected officials may also be more willing to engage in corrupt acts within the bureaucracy).

At the core of this discussion is an issue of loyalty and values. When merit principles govern employment processes, civil servants will take direction from their government, but will be loyal to each other and to their shared values. In this way, merit systems and common public sector values are intrinsically linked and provide an important countervailing force to political power, which may prioritise popularity to win elections and/or rent seeking for personal profit over serving the public good.

The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity recommends that adherents “promote a merit-based, professional, public sector dedicated to public service values and good governance, in particular through:

a. ensuring human resource management that consistently applies basic principles, such as merit and transparency, to support the professionalism of the public service, prevents favouritism and nepotism, protects against undue political interference and mitigates risks for abuse of position and misconduct;

b. ensuring a fair and open system for recruitment, selection and promotion, based on objective criteria and a formalised procedure, and an appraisal system that supports accountability and a public service ethos” (OECD, 2017[5]).

The Recommendation’s principle of merit requires staffing processes to be based on ability (talent, skills, experience, competence) rather than social and/or political status or connections. In governance, merit is generally presented in contrast to patronage, clientelism, or nepotism, in which jobs are distributed in exchange for support, or based on social ties.

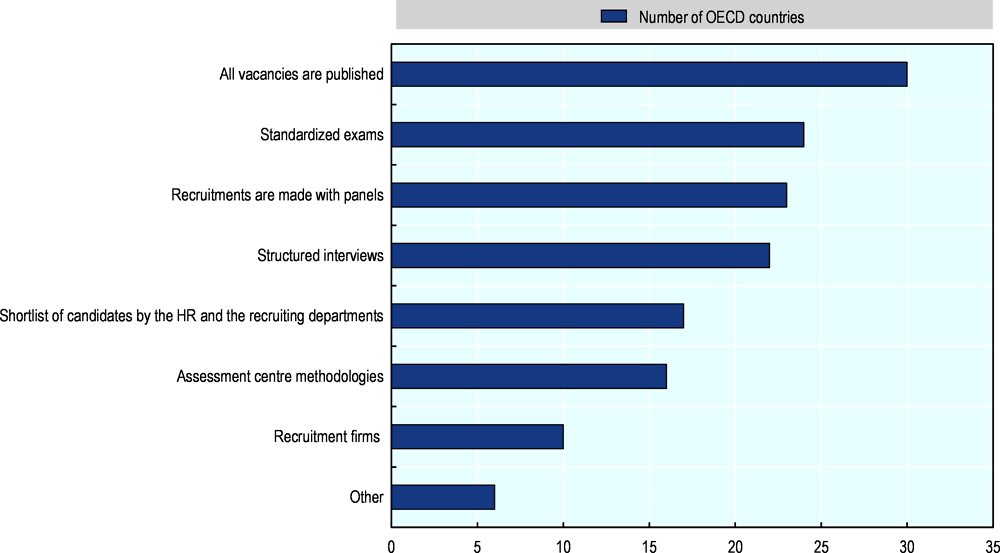

But what does merit mean in practice? Depending on the country and context, there is a wide range of tools, mechanisms and safeguards that OECD countries use to promote and protect the merit principle in their public administrations. For example, a majority of OECD countries publish all vacancies, use some form of standardised exams as well as structured interview panels (Figure 7.1).

Regardless of the specific tools, the following features are all essential components of meritocratic policies:

Predetermined appropriate qualification and performance criteria are in place for all positions.

Objective and transparent personnel management processes are in place against which candidates are assessed.

Open application processes are established and ensure opportunity for assessment to all potentially qualified candidates.

Oversight and recourse mechanisms are established and ensure fair and consistent application of the system.

7.2.1. Predetermined appropriate qualification and performance criteria are in place for all positions

In order to have a merit-based civil service system, a transparent and logical organisational structure needs to clearly identify positions and describe the role and work to be performed in this position. This ensures that the creation of new positions is done with the right intent, based on functional needs. In systems where patronage and nepotism are high risks, it is necessary to make the full organisational chart open to public scrutiny. In systems where such behaviour is less common, clear criteria for the creation of new positions and some level of oversight – for example, a central HR authority or the ministry of finance – is usually applied, to ensure a common approach and common standards are maintained. The experience of Estonia in developing common job families presents an example of successfully integrating a common job structure across public organisations that had each developed their own systems (Box 7.1).

Estonia began to introduce the concept of job families in the civil service in 2009. The main goal was to have comparative data on the salary levels in different organisations, which were not standardised due to the highly decentralised HR management system of the Estonian civil service.

Estonia used an analytical job evaluation system where jobs with common characteristics (e.g. lawyer, IT specialist, training manager, project manager, etc.) are grouped into job families with different levels of responsibility (e.g. HR Clerk – HR Specialist – HR Manager – HR Director).

Introducing analytical job evaluation in the Estonian civil service proved difficult since the concept was alien to the mentality of civil service. However, progress was made in 2011 when the Ministry of Finance, in co-operation with a private contractor, drafted the first version of the job catalogue. Together with colleagues in HR departments, the Ministry of Finance evaluated 13 400 jobs in 24 civil service organisations (out of 22 000 jobs in civil service at the central government level).

This was done on a voluntary basis, as there was no mandate for this type of job classification in the legislation until the new Civil Service Act came into force in 2013. However, by 2012 most of the civil service organisations were using this system. One of the lessons that can be drawn here is that, if implementers understand the value of the major change, it is easy to introduce that change in work practices that require considerable effort for the implementers.

Source: Information provided by the Estonian peer for the Public Governance Review of the Slovak Republic.

Once positions are clearly identified and justified, criteria for selection linked to the specific tasks to be performed help to guide an objective selection process. Criteria may include categories such as specific abilities, skills, competencies, knowledge, expertise, experience and education. Merit systems generally strive for criteria that are specific, objective and measurable. This can be a challenge when it comes to behavioural and/or cognitive competencies, which are harder to assess and rank but which are increasingly vital as predictors of success, particularly at management and leadership levels. Linking these to classic competencies is an important step and most OECD governments do so through job profiling, which helps not only to describe the tasks, but also to focus on the outcomes of the job, and the skills and competencies needed to achieve them (Box 7.2).

Job profiling is a way of combining a statement about what is expected from a job with a view of what the job holder must bring in terms of the skills, experience, behaviours and other attributes needed to do the job well. It is an approach that helps organisations think about the outputs and results they want from jobs as well as what they are looking for in terms of the person who will perform the corresponding duties.

Job profiles differ from traditional job descriptions in two important respects:

They focus on the outputs or results expected from the job rather than, as in the case of traditional job descriptions, the tasks or functions to be carried out.

They include a statement about the skills and personal attributes needed for the job.

Job profiles help to determine the criteria for both selection and performance in a post. Job profiles are best when based on objective job analysis methods, which ideally include expert input and engagement with people who do those jobs. Job profiles usually include some combination of the following:

job title

purpose of the post (oriented towards objectives and goals of the organisation)

scope of the post (some sense of the range of responsibility, relationships internal and external to the organisation)

principal duties and responsibilities (what this post will be accountable for achieving)

skills and knowledge (can include behavioural and cognitive competencies, often oriented toward a competency framework)

experience

personal attributes (e.g. personal values, including integrity).

Source: (OECD, 2011[7]).

While identifying the right criteria and measuring it appropriately is an ongoing challenge even for the most advanced public employers (which will be discussed further in Section 7.3.2), Box 7.3 gives the example of the Australian Public Service’s assessment of work-related qualities.

Employment decisions in the Australian Public Service (APS) are based on merit, which is one of the employment principles of the service. At a minimum, all employment decisions should be based on an assessment of a person’s work-related qualities and those required to do the job. For decisions that may result in the engagement or promotion of an APS employee, the assessment must be competitive.

Under the Public Service Act 1999, a decision is based on merit if:

It is based on the relative suitability of the candidates for the duties, using a competitive selection process.

It is based on the relationship between the candidates’ work-related qualities and the work-related qualities genuinely required for the duties.

It focuses on the relative capacity of the candidates to achieve outcomes related to the duties.

Merit is the primary consideration in taking the decision.

For the assessment to be competitive, it must also be open to all eligible members of the community. For ongoing jobs and non-ongoing jobs of more than 12 months’ duration, this is achieved by posting the job in the APS Employment Gazette on the APS jobs website.

The work-related qualities that may be taken into account when making an assessment include:

skills and abilities

qualifications, training and competencies

standard of work performance

capacity to produce outcomes from effective performance at the level required

relevant personal qualities

demonstrated potential for further development

ability to contribute to team performance.

Source: Information provided by the Australian Public Service Commission.

Performance criteria are also a key feature of a meritocratic system. Performance criteria help to clarify what the person in the position is expected to achieve in a given period and how these achievements will be assessed. Performance criteria reinforce meritocracy in two interrelated ways. The first is that it contributes to an understanding of whether or not the current incumbent is appropriate for the post. Merit should not only be determined at the selection process, but also be reinforced and reassessed at regular intervals. Even the best selection processes may make mistakes, and strong performance assessment processes help to safeguard against these. Additionally, roles can change based on new political priorities or operational demands. In these cases, updated performance criteria can be used to reassess the person in the position to ensure they remain the right fit.

The second way that performance criteria and assessment contribute to meritocracy is by assessing the future potential of a particular employee. An employee’s performance record is an important piece of information about the individual’s abilities and competencies, and can provide insight that is hard to test in job selection processes. Provided that they are conducted against well-defined and objective performance criteria to avoid their arbitrary use against or in favour of particular staff members, performance assessments can be a valuable complementary input to inform selection processes when employees apply for a new position or a promotional opportunity.

7.2.2. Objective and transparent personnel management processes are in place against which candidates are assessed

Many discussions of merit-based public employment emphasise the process of entry into the civil service or public institutions, as this is generally the first line of defence against nepotism and patronage. That is the rationale behind for instance the competitions organised in Spain or France to enter the civil service. In Spain candidates go through a competitive recruitment process, that guarantees objectivity, neutrality, merit, capacity, publicity and transparency principles, as well as professionalism and the neutrality of the collegial selection body. There are also administrative and judicial appeal mechanisms at all phases of the process. However, in a merit-based civil service, the merit principle applies to all personnel decision-making systems, including performance management; all appointment processes whether internal (promotions/lateral mobility) or external (hiring); training and development opportunities; pay systems; discipline; and dismissal.

In general, the following principles should be applied to all of these processes:

Transparency – In most merit systems, HR decisions are made openly, to limit preferential treatment accorded to specific people or groups. Decisions are generally documented in such a way that key stakeholders, including other candidates, can follow and understand the objective logic behind the decision. This enables them to challenge a decision that seems unfair. Tools and practices may include online systems that are increasingly used to track HR processes and publish the results.

Objectivity – Decisions should be made against predetermined objective criteria (see Section 7.2.1 above) and measured using appropriate tools and tests that are accepted as effective and cutting-edge by the HR profession. Tools and practices may include standardised or anonymous curricula vitae, standardised testing, assessment centres, panel interviews, competency tests, personality tests, situational judgement tests, and other methods intended to inform the process. In all cases, tests are best selected in consultation with professional psychologists and used as one input among many.

Consensus – Decisions should be based on more than one opinion and/or point of view. Multiple people should be involved, and efforts should be taken to strive for a balance of perspectives, particularly with regard to processes that are less standardised and open to subjective interpretation, such as interviews or written (essay) examinations. This can help to improve objectivity and limit favouritism based on personal relationships (e.g. promoting someone because they are liked by their manager) and can also help to address unconscious bias. Tools and practices may include the use of panel interviews, with a balance of gender, age, and expertise. The use of 360-degree feedback – which gives an employee the opportunity to receive performance feedback from subordinates, colleagues and supervisors, and usually includes an individual self-assessment – can also help to bring in multiple perspectives to HR decision making.

In merit systems, these principles equally apply to dismissal. A high level of job security has been a common feature of public employment systems in many countries, and was generally established to protect civil servants from politically motivated dismissals, ensure their right to provide frank and fearless policy advice, and allow them to “speak truth to power”. Today, many features of civil service personnel management are being rethought in the context of a modern labour market, and job protections are debated in the political arena in many countries. For the purposes of a merit-based system, protection from politically motivated dismissal is essential. However, dismissal in the case of significant underperformance is also part of the system in most OECD countries, although it is rarely applied except in cases of overt misconduct. The challenge is in carefully defining the line between performance and politics, and protecting against the potential for abuse. This suggests the need to actively manage performance.

Box 7.4 discusses how personnel management processes in the Polish Civil Service are managed between the head of civil service and the directors general of each government office.

The head of the civil service in Poland is appointed by and reports directly to the prime minister. Their role includes co-ordinating civil service personnel policy and harmonising merit-based HRM tools implemented in a decentralised manner to avoid fragmentation. Indeed, the HRM system in the Polish civil service is decentralised; each government office is responsible for its human resource policies. Therefore, the head of civil service must execute their tasks with the assistance of the directors general of offices – the highest position in the civil service system – who perform activities envisaged under the labour law in relation to persons employed in their government office and are responsible for staffing policy (they act as government employers).

There are some aspects of merit-based HRM left exclusively to the competence of the head of civil service and exercised centrally. In the field of recruitment, the head of civil service exercises substantive supervision over the database of job vacancies in the service (with the exception of senior positions). Every director general/head of office must publish vacancies on this database. The Civil Service Department, which provides support to the head of the service in carrying out their duties, monitors the compliance of job advertisements with legal requirements, including with civil service rules and ethical principles, to ensure that the recruitment process is transparent, open and based on the competition principle. In case of irregularities, the head of civil service makes recommendations to correct them and controls their implementation.

The head of civil service also chairs regular meetings with the directors general in order to share information, discuss “hot issues”, and collaborate on drafts of solutions in working teams.

Other tools which the head of civil service uses to reinforce and standardise application of the merit principle across the civil service include:

Creation and appointment of various committees, such as opinion or advisory bodies, on issues related to the civil service. There could for example be committees on HRM standards, ethics and civil service rules, a remuneration system, job descriptions, and evaluation of the higher positions in the civil service. In general, these bodies include experts from academia and civil society, the private sector, and civil service executives.

Use of soft law instruments such as ordinances, guidebooks and recommendations (for example on promoting the culture of integrity in the civil service).

Use of supervision instruments, such as audit and control (performed by the minister of finance and the prime minister) of the activities conducted under the Law of Civil Service. These might be of a binding and supporting nature for the directors general.

Development of drafts of the secondary legislation issued by the prime minister stipulated in the Law on Civil Service, e.g. on performance appraisal, ethical principles, or qualification procedures. This creates a consistent merit-based framework for the whole civil service and at the same time leaves the directors general the flexibility to adapt and implement.

Implementation of uniform tools for the whole civil service, such as job description and evaluation, recruitment procedures, performance appraisal, and disciplinary procedure.

Source: Civil Service Department, Polish Chancellery of the Prime Minister.

7.2.3. Open application processes are established and ensure opportunity for assessment to all potentially qualified candidates

A third fundamental component of merit is the principle of open and equal access. This is key, as it helps to ensure that the best person for the job is able to come forward and be considered regardless of their location, demographic characteristics, social status, or political affiliation. To achieve this, merit-based civil services in OECD countries make efforts to ensure that job openings and relevant information are advertised and communicated, that access points for testing and interviews are geographically dispersed, and that all reasonable efforts are made to facilitate groups who may be disadvantaged, such as people with disabilities. In Spain for instance, specific provisions aim to foster diversity in recruiting public employees including people with disabilities, through specific measures such as quotas. These measures aim at eliminating discriminatory obstacles, provided the candidates passed the selection procedures indicating the same level of competencies and knowledge as other candidates. A system that limits consideration to specific segments of society cannot be considered to be fully meritocratic, regardless of the assessment criteria and tools used.

This principle calls for real reflection on the way criteria for selection are chosen and assessed. For example, do educational criteria benefit graduates from specific schools that may be known to be primarily attended by an elite class? Such criteria can perpetuate the notion of a ruling class, which is contrary to the basic principle of merit. In fact, linking merit to educational criteria requires careful consideration of whether/how the merit principle is applied in the education system. In some countries, access to education is determined more by means than merit, which by extension can result in an elitist civil service. To address this some countries, such as Belgium, enable educational criteria to be substituted with experiential criteria when a clear case can be made.

Some OECD countries analyse selection criteria and recruitment processes in terms of demographic factors to assess whether they encourage applications from women or minority groups. The United Kingdom has undertaken a thorough analysis of applicants to the Fast Stream programmes and found that the applicant pool misses some key aspects of representation (Box 7.5). If surprisingly low numbers of applications are received from certain groups, further study can be conducted to understand why they are not applying and to address barriers. Sometimes the barrier is perception – in some societies certain groups do not perceive the civil service as being a place where they would be welcome to work. This can be a powerful signal as to the level of merit, real or perceived, in the system.

The Fast Stream is one of the largest graduate development programmes among OECD countries. In 2015, 21 135 applicants competed for 967 appointments in 12 different specialist and generalist streams.

Once selected, programme participants are equipped with the knowledge, skills and experience they need to be the future leaders of the civil service. Fast Streamers' personal development is achieved through a programme of carefully managed and contrasting postings, supplemented by formal learning and other support such as coaching, mentoring and action learning.

The UK Fast Stream programme promotes diversity and inclusion, and produces an annual report with data and analysis showing the range of applicants. This is a good example of data-driven HR analysis. In 2015, a report was produced to understand the factors behind the socio-economic patterning in the Fast Stream and why applicants from lower socio-economic backgrounds are less likely to apply and less likely to succeed. The research provided insight for the wider civil service and evidence to build on for formulating recommendations to improve socio-economic diversity.

The report included recommendations to (among other things) introduce a new, enhanced approach to measuring and monitoring socio-economic diversity; establish clearer accountability for socio-economic diversity in the Fast Stream; and introduce enhanced data insights to adjust attraction and recruitment strategies.

Source: (OECD, 2017[8]) (The Bridge Group, 2016[9]).

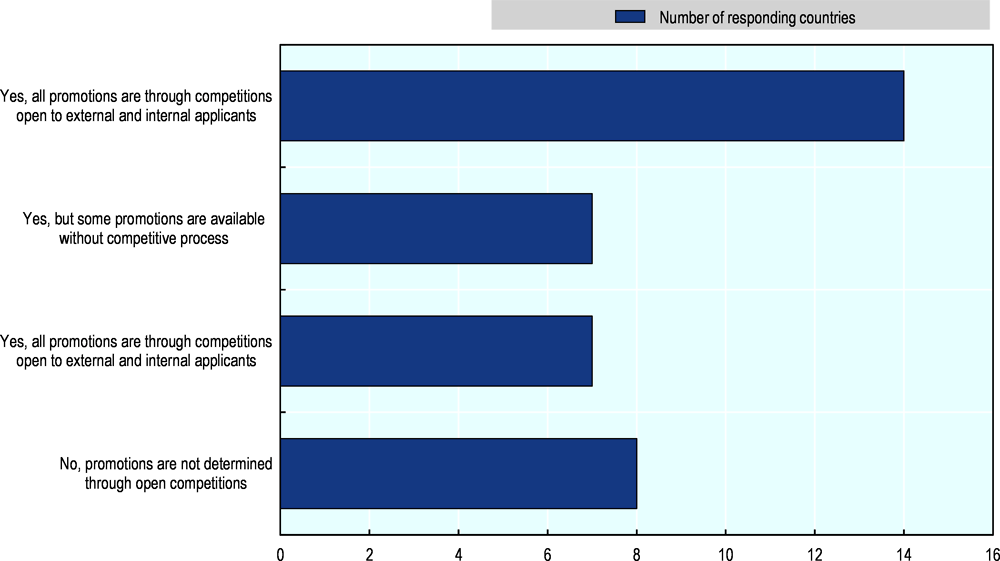

When applied to internal HR processes, this principle should be adjusted to the particular circumstances of the civil service system in question. Not all positions need to be filled through competitions open to external candidates. Figure 7.2 suggests that only a minority of OECD countries open all recruitment to external competition. However, there should be clear and transparent criteria and reasoning behind the use of internal versus external competitions. Additionally, internal competitions should still be open to all qualified internal candidates.

7.2.4. Oversight and recourse mechanisms are established and ensure fair and consistent application of the system

As with any rule-based system, institutions and processes need to be in place to ensure consistent and fair application. This is particularly important when responsibility for HRM is highly distributed – as it is in most OECD countries, where individual managers have a high degree of influence in hiring, performance assessment and promotion. With so many people involved, the risk is high for irregular application, and for personal interpretations of the rules and principles that result in uneven application or even in disagreement about what the rules and principles mean. Most countries address these issues through three interrelated mechanisms.

The first is to assign authority for the oversight and protection of the merit system to an independent body with investigative powers and authority to intervene in HR processes when breaches are deemed to have happened or to be imminent. In most cases the body’s primary role is to safeguard the process and correct the system when necessary (Box 7.6). For example, these authorities can monitor that job advertisements comply with legal requirements, regulations and ethical principles, as well as monitor the transparency of the recruitment process. In some countries the authorities also conduct testing and selection procedures on behalf of individual organisations.

The second is to have recourse mechanisms available to candidates who feel they have been treated unfairly. Providing candidates with access to their personal file and records is a prerequisite. Candidates need to be made aware of the recourse means, and the mechanisms should be accessible and resourced appropriately to ensure responsiveness.

The third is to ensure that all managers have a clear and consistent understanding of the system and their discretion within it. This is most often accomplished through a combination of information provision, mandatory and regular training, and advisory services.

Ireland: The Commission for Public Service Appointments is an independent body that sets and safeguards standards for recruitment and is bound by law to ensure that recruitment and selection are carried out by fair, open and merit-based means. Its primary statutory responsibility is to set standards for recruitment and selection, which it publishes as Codes of Practice. The Commission safeguards these standards through regular monitoring and auditing of recruitment and selection activities, and it investigates alleged breaches of the Codes of Practice.

Canada: The Public Service Commission (PSC) is an independent agency responsible for safeguarding the values of a professional public service: competence, non-partisanship and representativeness. The PSC safeguards the integrity of staffing in the public service and the political impartiality of public servants. The PSC can investigate external appointments; internal appointments, if not delegated to an organisation; and any appointment process involving possible political influence or suspected fraud. All external and internal appointments are made by the PSC, although authority to make appointments can be delegated to the most senior civil servants (deputy ministers). Deputy ministers must respect PSC appointment policies in exercising their delegated authority and are held accountable to the PSC for the appointment decisions they make, through mechanisms such as monitoring, reporting, studies, audits, investigations and corrective actions. The PSC may limit or remove delegated authority from a deputy minister. In turn, the PSC is accountable to parliament for the integrity of the public service appointment system.

United States: The Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) is an independent, quasi-judicial agency in the executive branch that serves as the guardian of federal merit systems. The MSPB is empowered to hear complaints and decide on corrective or disciplinary action when an agency is alleged to have committed a prohibited personnel practice. The MSPB carries out its statutory responsibilities and authorities primarily by adjudicating individual employee appeals and by conducting merit systems studies. In addition, the MSPB reviews the significant actions of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to assess the degree to which those actions may affect merit. The Office of Special Counsel (OSC) is an independent executive agency that investigates allegations of prohibited personnel practices, prosecutes violators of civil service rules and regulations, and enforces the relevant legislation.

Source: Ireland – Commission for Public Service Appointments, www.cpsa.ie/en/; Canada – Government of Canada, Public Service Commission, www.canada.ca/en/public-service-commission.html; United States – United States Merit Systems Protection Board, www.mspb.gov/ (all accessed 22 February 2020).

While merit systems have been a constant principle in civil service management across OECD governments, application of the system needs to be renewed in order to keep up with the changing demands of civil services. In many ways, merit systems that were put in place are being reviewed in light of these changing needs and expectations.

At the core of the tensions in the merit system is the perception that meritocracies are less responsive to the desires of the political officials elected to represent their constituencies. Hiring and staffing processes, it could be argued, would be more adaptive and quicker to respond to emerging challenges in a private sector type of system that does not impose the same standards or checks and balances on merit. In these systems, transparency and fairness are traded for expedience. Whether or not this is true, and what the longer-term trade-offs are in terms of public value and democratic principles, demand public debate and analysis that look beyond the short-term views of the political cycle. Most systems have some flexibility and use exceptions to the merit rules sparingly, to ensure that they remain exceptions to the rule and do not become the rule.

What is clear is that if merit-based systems are not updated to meet the needs of a 21st century government, they will create incentives for managers to resist the meritocratic nature of the system and find ways to cut corners.

7.3.1. Speed and timely decision making

Central to this discussion is the speed of many merit systems, which can often be reduced due to the various stages required in assessing candidates, and the necessity to ensure that candidates have ample opportunity to challenge a decision they see as unfit. From a management perspective, operational demands not met by a slow merit system can create incentives to look for other kinds of staffing mechanisms, such as using temporary contracts or promoting people on a temporary basis, which can undermine the merit system.

A public sector merit-based system, which values openness and transparency, may always be slightly slower than alternative systems that can skip various steps in the process. However, many countries could speed up their staffing processes by making better use of digital technologies and investing in the skills and capacities of HR managers to conduct more strategic approaches to staffing. To assist recruiters and managers, the Australian Public Service Commission has developed guidance to increase compliance of the internal HR processes with the legal framework, and ease decision making without slowing the system (Australian Public Service Commission, 2018[10]).

A number of countries, such as Canada, have developed pooling systems that can also help speed up the process from a management perspective. In this system, candidates prequalify for certain types of positions, and hiring managers can go to this candidate “pool” to find a suitable fit without having to run an entire process from the beginning. However, from a candidate’s perspective, the process can take a long time, and good candidates may already find work elsewhere. Skills pools are also developed internally to offer a cross-governmental resource. The free agents programme in Canada creates a pool of internal civil servants with innovation skills, and assigns them to short-term projects in various departments to help meet specialised needs.

7.3.2. Keeping up with new skills and competencies

A second factor straining traditional merit systems is the kinds of skills and criteria that are being assessed. On the one hand, skill sets in the public sector are becoming increasingly specialised and technical (e.g. for detecting corruption), suggesting that the traditional standardised examination approach may be of less relevance.

On the other hand, public employers are increasingly using behavioural and cognitive competencies (e.g. teamwork, strategic thinking and management skills) and values (e.g. integrity) as selection criteria for positions. The challenges of using merit systems to detect integrity and screen out people whose values do not align are significant, for a number of reasons:

It is less people’s character traits and more the context in which they find themselves that contributes to their decision to engage in corruption or unethical behaviour;

The few people who may approach a job with specific intent to undertake unethical activities are likely prepared to deceive and game the detection system to achieve their ends;

There is no consensus on the benefits or reliability of integrity tests used for pre-screening candidates primarily in the private sector.

This situation requires a new set of assessment tools and expertise. Without investing in such expertise, assessment of these kinds of factors is open to subjective interpretation and unconscious bias, which can threaten the validity of the merit process and open the door to nepotism. The bottom line is that the ability of the traditional merit-based approach to select the best candidates (i.e. education, experience and standardised examinations) may no longer be appropriate for the needs of a modern public service organisation.

Given these challenges, some governments may specifically test awareness and knowledge of ethical procedures, and use situational judgement exams to get a view of the candidates’ judgement capacity.

Values-based assessments can also provide insight on the values fit, which can be an important indicator of future performance. Generally, the first step is for an organisation to clarify which values are integral to its work. This should go beyond simply listing key words such as “integrity” and “accountability”, and include a description of which behaviours illustrate these values in a work context. The behaviours then become part of the assessment criteria along with skills, experience and aptitude.

Testing for these behaviours is not simple and requires some degree of expertise. It can be used in interview settings, for example; some organisations may ask candidates to discuss their own values straight out. However, a better way is often to learn them indirectly – by asking, for example, about a time when the employee was forced to make an ethical decision at work, or about a time when they felt there was a value conflict, and then looking for the behaviours identified earlier. Even better is to have the candidates demonstrate their values through assessment centre methodologies such as role-playing, simulations and group exercises. Gamification is increasingly used as a way to assess behaviours and values in a more natural setting, but such approaches require careful controls in the hands of psychological experts to ensure reliability and validity.

7.3.3. The challenge of representation and inclusion

Two values that are increasingly guiding public employment and management are those of representation and inclusion. Workforce diversity in an inclusive environment can improve policy making and service delivery innovation. Having a range of employees with different backgrounds who see things from different perspectives may also contribute to a workplace culture where employees are open to questioning assumptions and identifying integrity risks. The Australian Public Service Commission developed guidance material aimed at increasing diversity and inclusion in the Australian Public Service workforce, including for instance guidance in designing affirmative measures for recruiting indigenous people or persons with disabilities (Australian Public Service Commission, 2018[10]).

Across OECD countries, the top levels of bureaucratic hierarchies are less diverse and less representative of the general population than the broader public sector workforce. This suggests that the merit systems that select and promote people for top-level positions may be biased towards certain profiles, and could be reviewed with this in mind.

Bias can be built into the system, and/or it can be part of the personal (unconscious) bias of decision makers. Biases that can be built into the system may include criteria that unnecessarily exclude certain populations, such as preference for certain education that is only accessible by upper class populations, or the location of recruitment facilities in capital cities. Mentorship programmes can also help address imbalances in the development of social networks, which often play a role in promotion, as can strong policies that aim to balance work and family life.

The unconscious bias of decision makers can be addressed and managed, beginning with mandatory awareness training for all managers. Managers need to understand their biases not only in hiring, but also in performance management (which has a significant impact on promotion) and task assignment (e.g. women may be assigned fewer opportunities to work on high-profile, demanding projects because they are assumed to prioritise family life). Making these kinds of personnel decisions in consultation with other managers, superiors or even other team members can be a way of challenging managers’ personal biases (Evans et al., 2014[11]).

7.3.4. The fragmentation of public employment

When many civil service systems were established, it was on the understanding that public employment was unique and separate from private employment, and therefore warranted its own system and legal framework. Today’s civil service systems tend to be much more fragmented, and civil servants find themselves increasingly working alongside private contractors and/or people on temporary contracts that may not be subject to the same meritocratic principles and protections. Furthermore, an increasing number of public services are delivered on behalf of the government through third-party contractors and not-for-profit/third-sector organisations. Traditional civil service merit rules generally do not apply.

This raises important questions about the current state and future of meritocratic systems. For example, should citizen-facing service third-party delivery organisations be subject to a minimum set of standards for merit regardless of whether they are public sector or not? Or does their distance from the political interface remove the most immediate threat of political interference, from which merit was designed to protect? Given the amount of public money that many of these organisations handle, some suggest that they should be subject to some kind of minimum capacity measures. For example, the European Commission has developed a competency framework that can be applied to managing authorities that receive EU structural funds (European Commission, n.d.[12]); the framework can guide their merit processes and help to identify strengths and gaps.

A related question is whether all public employees should be subject to the same merit criteria regardless of their employment status (e.g. civil servants, temporary employees, etc.). This would likely depend on whether the civil servants do the same job as other public employees. The level of meritocracy would likely be determined by a kind of risk assessment based on the qualities of the job, and not on the specific legal contracting mechanism in place.

References

[10] Australian Public Service Commission (2018), Recruitment: Guidelines, https://www.apsc.gov.au/recruitment-guidelines (accessed on 24 September 2019).

[4] Charron, N. et al. (2017), “Careers, Connections, and Corruption Risks: Investigating the Impact of Bureaucratic Meritocracy on Public Procurement Processes”, The Journal of Politics, Vol. 79/1, pp. 89-104, https://doi.org/10.1086/687209.

[1] Cortázar, J., J. Fuenzalida and M. Lafuente (2016), Sistemas de mérito para la selección de directivos públicos: ¿Mejor desempeño del Estado?: Un estudio exploratorio, Inter-American Development Bank, https://doi.org/10.18235/0000323.

[2] Dahlström, C., V. Lapuente and J. Teorell (2011), “The merit of meritocratization: Politics, bureaucracy, and the institutional deterrents of corruption”, Political Research Quarterly, Vol. 65/3, pp. 656-668, https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912911408109.

[12] European Commission (n.d.), EU Competency Framework for Management and Implementation of the ERDF and Cohesion Fund, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/how/improving-investment/competency/ (accessed on 11 October 2019).

[11] Evans, M. et al. (2014), “‘Not yet 50/50’ - Barriers to the Progress of Senior Women in the Australian Public Service”, Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 73/4, pp. 501-510, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12100.

[3] Meyer-Sahling, J. and K. Mikkelsen (2016), “Civil Service Laws, Merit, Politicization, and Corruption: The Perspective of Public Officials from Five East European Countries”, Public Administration, Vol. 94/4, pp. 1105-1123, https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12276.

[5] OECD (2017), OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Integrity, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0435 (accessed on 24 January 2020).

[8] OECD (2017), Skills for a High Performing Civil Service, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264280724-en.

[6] OECD (2016), Survey on Strategic Human Resources Management in Central / Federal Governments of OECD Countries, https://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?Subject=GOV_SHRM.

[7] OECD (2011), Public Servants as Partners for Growth: Toward a Stronger, Leaner and More Equitable Workforce, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264166707-en.

[9] The Bridge Group (2016), Socio-Economic Diversity in the Fast Stream, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/497341/BG_REPORT_FINAL_PUBLISH_TO_RM__1_.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2019).